HIV/AIDS at 30: A Public Opinion Perspective

Section 3: Young Adults and the Domestic Epidemic

Americans under age 30 have never known a world without HIV. Many of them likely take for granted the concept that there are treatments to prolong the lives of those with HIV, treatments that did not exist when their parents and grandparents first learned about the illness. They are part of a generation whose attitudes on some social issues, particularly those concerning gays and lesbians, are also considerably more liberal than their elders. And as they begin their adult years, their attitudes, knowledge and behaviors around the topic of HIV will impact efforts to reduce the spread of the virus going forward. In this section, we take a closer look at 18 to 29 year olds, with a special emphasis, as in earlier sections, on those in the black community.

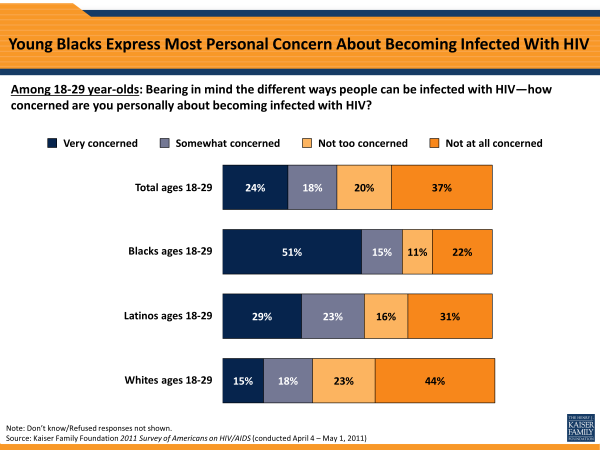

Young Adults Most Concerned About Infection, Driven By Intense Concern Among Young Blacks

Young adults—less likely to be in monogamous relationships, more likely to report having multiple sexual partners1 —are the age group most likely to express personal concern about contracting HIV. Overall, 42 percent are at least somewhat concerned about this possibility, and the proportion that reports being “very concerned” ticked up this year for the first time in nearly fifteen years, from 17 percent two years ago to 24 percent now.

But that statistic glosses over a vast racial gap in concern among those under age 30. Young black adults, who have been disproportionately impacted by the domestic epidemic and account for 55 percent of all reported HIV infections among those aged 13 to 24,2 are much more likely than young whites to report worrying about HIV. Overall, fully half (51 percent) of blacks under 30 say they are very concerned about contracting HIV, and 66 percent are at least somewhat concerned. Most young whites express little concern about personal infection (67 percent say they have little or no worries on this front), and only 15 percent are very concerned. Young Latinos express concerns that put them somewhere between the other two groups.

Concerns about infection are likely driven in part by the extent to which even the youngest generation of American adults has seen the epidemic up close. Three in ten young adults report knowing someone living with HIV/AIDS or someone who died from the disease, fewer than among middle-aged Americans, but still a significant proportion given their relative youth. Again, however, younger blacks have been the most widely impacted. Three in ten have had HIV/AIDS impact their family or close friend group, compared to one in ten whites and two in ten Latinos in this age range.

| Figure 28: Reported Personal Connections With People With HIV/AIDS By Age And Race/Ethnicity | |||||||

| All adults by age | Adults Age 18-29 by Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Age 18-29 | Age 30-49 | Age 50-64 | Age 65+ | Blacks | Latinos | Whites | |

| Personally know someone who has HIV/AIDS or has died from AIDS | 31% | 46% | 51% | 30% | 44% | 37% | 27% |

| Yes, family member or close friend | 15 | 26 | 26 | 14 | 30 | 20 | 10 |

| Yes, acquaintance, coworker or someone else | 17 | 19 | 24 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 18 |

| No, don’t know anyone with HIV/AIDS or who has died of AIDS | 69 | 54 | 48 | 69 | 56 | 63 | 72 |

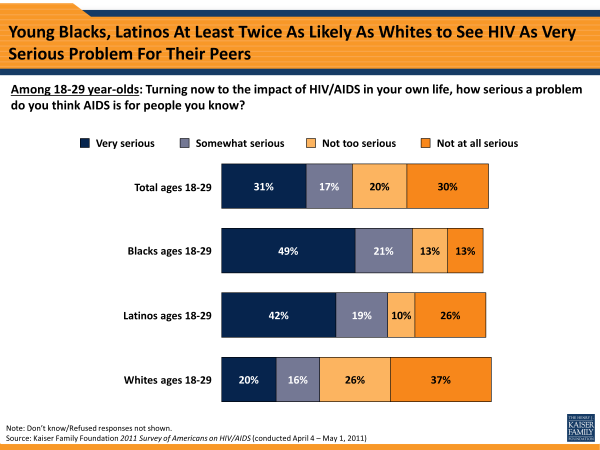

Young Blacks And Latinos See Impact On Community That Most Young Whites Don’t Feel

Overall, just under half (48 percent) of young adults say that HIV/AIDS is at least a somewhat serious problem for people they know, including three in ten (31 percent) who say it is a “very” serious problem. The large majority of young black adults (70 percent), and nearly as many young Latinos (61 percent), see HIV/AIDS as a serious problem for their friends and acquaintances, compared with just 36 percent of young white adults. Most young whites report that HIV/AIDS is not a problem for their peer group, or at least not a serious one.

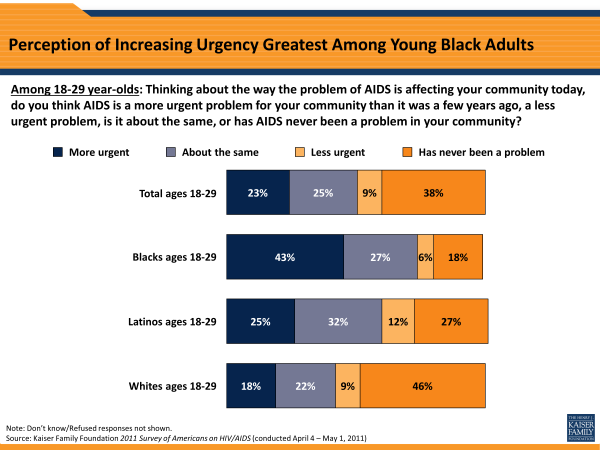

Similarly, asked about the urgency of the issue in their own community, young black adults are most likely to say the issue has become more urgent over the past few years (43 percent), while young white adults are most likely to say HIV/AIDS has never been a problem for their community (46 percent). Latinos’ responses are somewhat in the middle on this question.

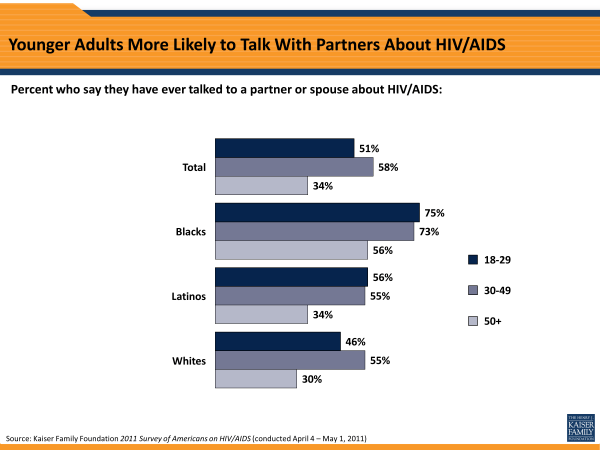

Talking About HIV/AIDS

Half of Americans aged 18 to 29 report having talked to a partner about HIV/AIDS, roughly the same as in 2009. Not surprisingly, those aged 50 and older are significantly less likely to report having had this experience. Reported conversations are highest among young black adults, with 75 percent reporting having talked to a partner about the disease, higher than the 56 percent of Latinos and 46 percent of whites in the same age group who report having done so.

| Figure 32: Percent Who Say The Subject Of HIV/AIDS Comes Up In Discussions With Their Family And Friends… | |||||

| Total | Age 18-29 | Age 30-49 | Age 50-64 | Age 65+ | |

| Often | 6% | 5% | 8% | 6% | 3% |

| Sometimes | 17 | 15 | 19 | 19 | 13 |

| Rarely | 41 | 40 | 44 | 40 | 34 |

| Never | 36 | 39 | 30 | 35 | 50 |

Despite their level of personal concern and the extent to which they are talking to their partners about HIV/AIDS, it’s worth noting that relatively few young people report talking about AIDS in general conversation. Overall, only 5 percent say the subject of HIV/AIDS comes up often when talking to family and friends, and another 15 percent say it sometimes comes up. In this regard, younger adults look much like their elders.

What Young Adults Know, And Where They Learn It

| Figure 33: Percent of Young Adults Saying The Following Statement Is True/False: “A Pregnant Woman Who Has HIV Can Take Certain Drugs To Reduce The Risk Of Her Baby Being Born Infected” | ||||

| Among those age 18-29 | ||||

| Total | Whites | Blacks | Latinos | |

| True | 53% | 51% | 70% | 49% |

| False | 30 | 33 | 22 | 31 |

| Don’t know | 17 | 16 | 8 | 20 |

Although young adults have grown up in the age of the AIDS epidemic, and most know the facts regarding transmission, the share of their age group harboring misconceptions is just as large as that among older generations. For example, 20 percent of young adults think a person can become infected with HIV by sharing a drinking glass or aren’t sure whether this is the case. Eighteen percent of young adults respond incorrectly or don’t know whether HIV can be transmitted by touching a toilet seat. Two in ten are confused as to whether there is a vaccine available to prevent HIV.

There are also cases where pertinent information has not spread widely throughout the population. For example, as they enter their childbearing years, almost half of all young adults (47 percent) don’t know that a pregnant woman with HIV can take certain drugs to reduce the risk of transmitting the disease to her baby, a similar level of knowledge as the rest of the population. Young black adults are more likely than their white and Latino peers to be aware of this fact: seven in ten are, compared to about five in ten among white and Latino young adults.

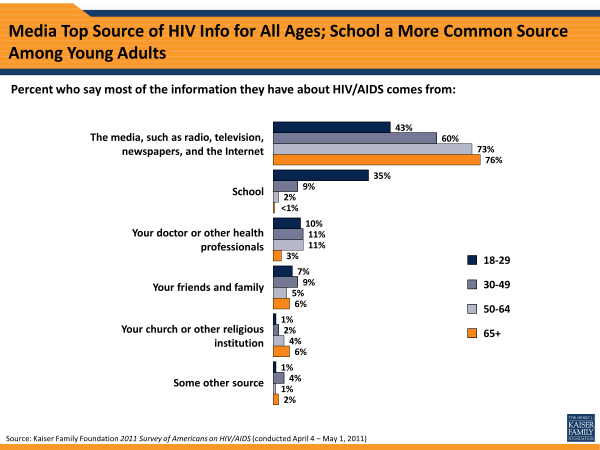

For adults of all ages, the media stands out as the primary source of information about HIV/AIDS. Among those ages 18-29, 43 percent say most of what they know about the disease comes from the media, and it is the top source for young whites (44 percent), blacks (47 percent) and Latinos (38 percent). But in an era where HIV/AIDS may increasingly come up in classroom situations, young adults, a group that is most likely to be currently in school or recently graduated, are much more likely than others to say school is their main source of information on HIV/AIDS: 35 percent say so, more than three times higher than any other age group.

It’s worth noting that young black adults are significantly less likely than whites or Latinos to name school as their main source of information: 20 percent of blacks do, compared to 39 percent and 33 percent of whites and Latinos, respectively. Perhaps not coincidentally, young black adults are more likely than their peers to say that public schools need to do more “to help solve the problem of HIV/AIDS in this country”—62 percent of young black adults say so, compared to 46 percent of whites and 48 percent of Latinos.

Young blacks and Latinos also express a desire to have more information on a number of topics related to HIV/AIDS, a desire less common among whites. The majority of blacks and Latinos say they would like to know more about how to: talk with children about HIV/AIDS, prevent the spread of the disease, find out who should get tested and where to go, and talk to a partner or doctor about the virus. While substantial groups of young white adults expressed interest in these topics, in no case did a majority report wanting or needing to learn more.

| Figure 35: Percent Of Young Adults Who Say They Would Like To Have More Information About Each Of The Following | ||||

| Among those age 18-29 | ||||

| Total | Whites | Blacks | Latinos | |

| How to talk with children about HIV/AIDS | 52% | 42% | 68% | 66% |

| How to prevent the spread of HIV | 50 | 41 | 66 | 61 |

| How to know who should get tested for HIV | 47 | 39 | 60 | 59 |

| Where to go to get tested for HIV | 47 | 38 | 59 | 64 |

| How to bring up the topic of getting an HIV test with your partner | 44 | 36 | 56 | 60 |

| How to talk with a health care provider about HIV/AIDS | 38 | 29 | 56 | 51 |

Liberalism of Youth: More Support For, And More Confidence In The Merits Of, Spending

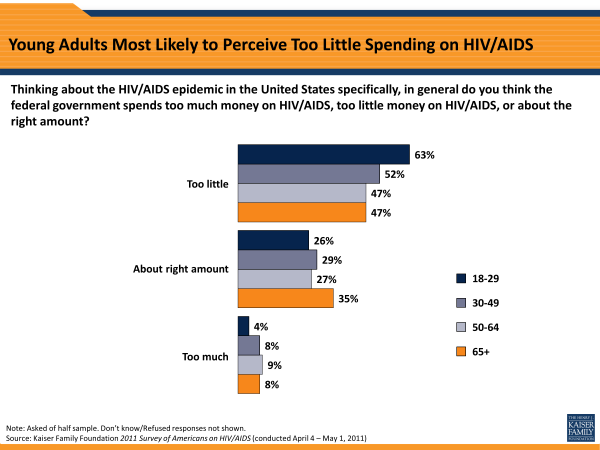

As surveys on political topics often find, the current generation of youth—a generation which was a key part of President Barack Obama’s electoral victory in 2008—has more liberal opinions on certain issues. When it comes to HIV/AIDS policy, adults under age 30 are the most likely to say the federal government is not spending enough to combat the disease.

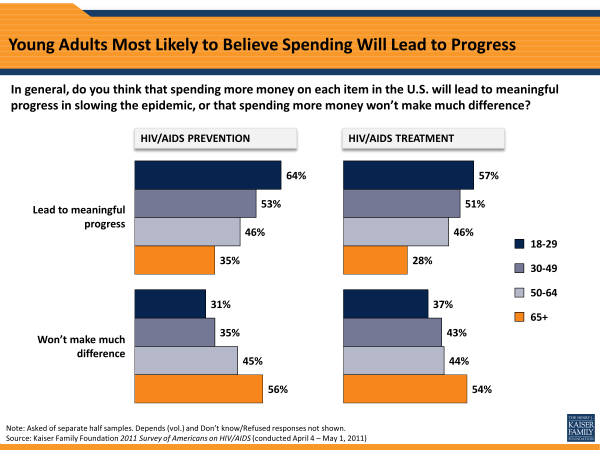

This support for increased spending is likely linked to the fact that young adults are markedly more likely to think that spending on HIV prevention will lead to meaningful progress: a full 64 percent do, compared to 35 percent of seniors. These age differences are apparent across racial and ethnic groups, with young white, black, and Latino adults expressing more liberal and optimistic attitudes about spending than their older counterparts.