Americans' Views on the U.S. Role in Global Health

Executive Summary

As policymakers react to global crises and the 2016 presidential election season ramps up, it’s an important time to understand Americans’ views on the U.S. role in global health. The Kaiser Family Foundation has tracked public opinion on global health issues in-depth since 2009. This most recent survey examines views on U.S. spending on health in developing countries and perceptions of barriers and challenges to making progress on the issue.

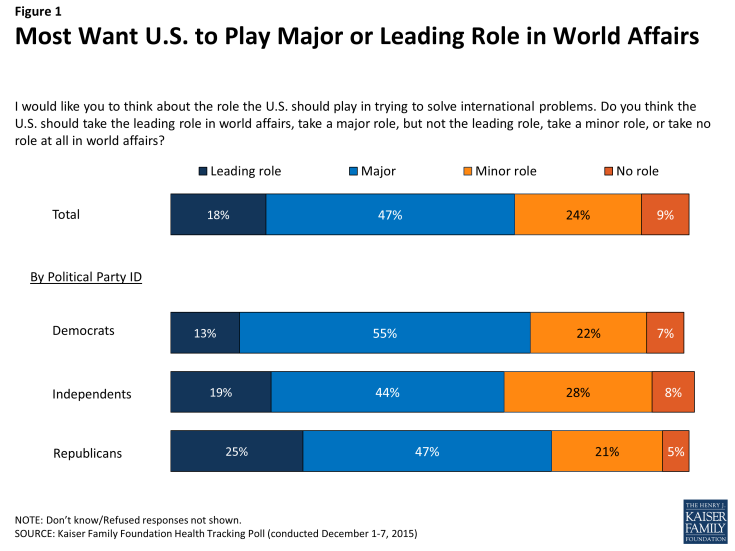

Two-thirds of Americans (65 percent) overall and majorities of Democrats, independents and Republicans alike, say that the United States should play at least a major role in world affairs, including roughly one in five overall (18 percent) who say the U.S. should take the leading role. However, when it comes to global health efforts specifically, about half (53 percent) say the U.S. government is already doing enough to improve health for people in developing countries, and nearly half (46 percent) feel that the U.S. is doing more than its fair share compared to other wealthy countries. In addition, most Americans prefer a collaborative international approach in global health efforts over the U.S. acting alone, and this sentiment has increased over the past several years. The survey also finds a general skepticism on the part of the American people when it comes to the effectiveness of global health spending, with seven in ten saying the “bang for the buck” of U.S. spending in this area is only fair or poor, and more than half believing that spending more on global health efforts won’t lead to meaningful progress (a share that has grown since 2012). Republicans, and to a somewhat lesser extent, independents, are more likely than Democrats to think that more spending will not lead to progress, to feel that the U.S. is already doing enough, and to say the U.S. is doing more than its fair share compared to other wealthier countries, and these differences between Democrats and Republicans have grown over time. Related to this general skepticism towards such spending, many point to a variety of perceived problems, including corruption and misuse of funds, as barriers to improving the health of people in developing countries.

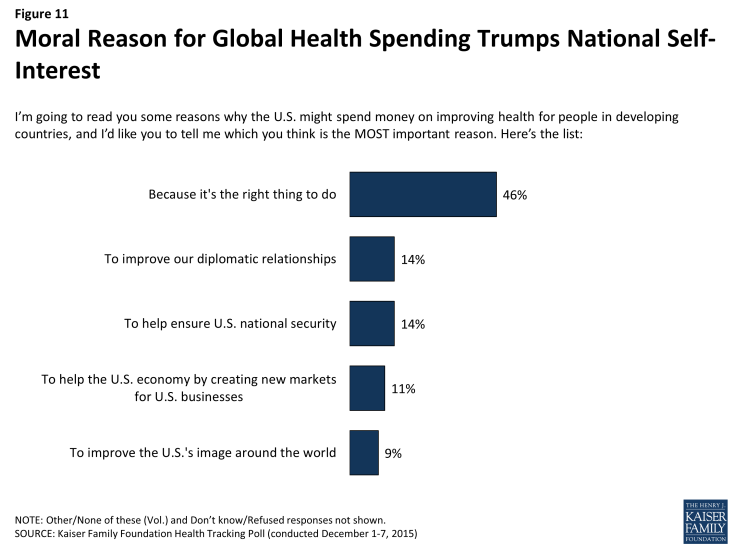

Although many Americans have concerns about the value of global health spending, six in ten say the U.S. spends too little (26 percent) or about the right amount (34 percent) on global health, and three in ten say it spends too much. Most also recognize benefits to such spending, both for Americans at home as well as for people and communities in developing countries. Nearly half (46 percent) say the most important reason for the U.S. to spend money on improving health in developing countries is because it’s the right thing to do, outranking other reasons, including improved diplomatic relationships (14 percent), national security (14 percent), or a stronger U.S. economy (11 percent).

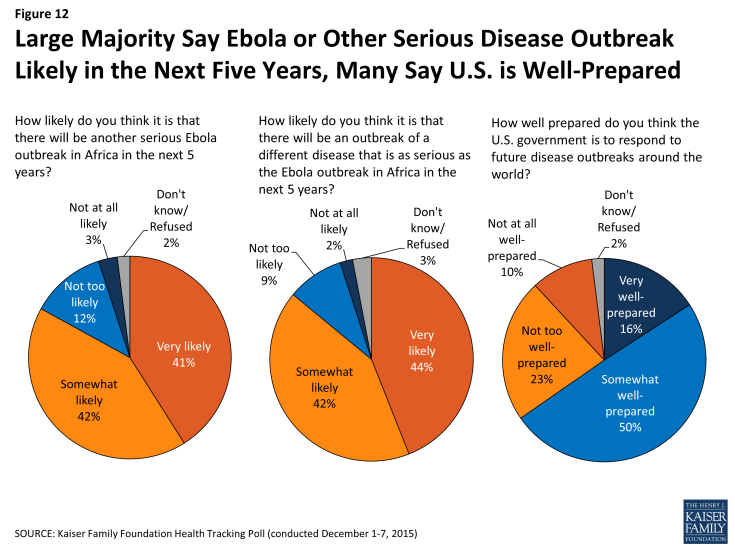

Looking forward, while a large majority of Americans think an Ebola or similar disease outbreak is likely in the next five years, two-thirds say the U.S. government is well-prepared to handle such an outbreak.

Views of U.S. Role in World Affairs and in Global Health Efforts

Broadly, the American public is largely supportive of the U.S. playing a large role in trying to solve international problems. About two-thirds of Americans (65 percent) say that the U.S. should play at least a major role in world affairs, including 18 percent who say the U.S. should take the leading role and 47 percent who say the U.S. should play a major role but not the leading one. Despite recent international events, including the Ebola crisis in West Africa as well as the more recent terrorist attacks in Paris, these shares haven’t changed substantially since 2012. Majorities across all parties say the U.S. should play a major or leading role, with Republicans more likely to say that the U.S. should play a leading role compared to Democrats.

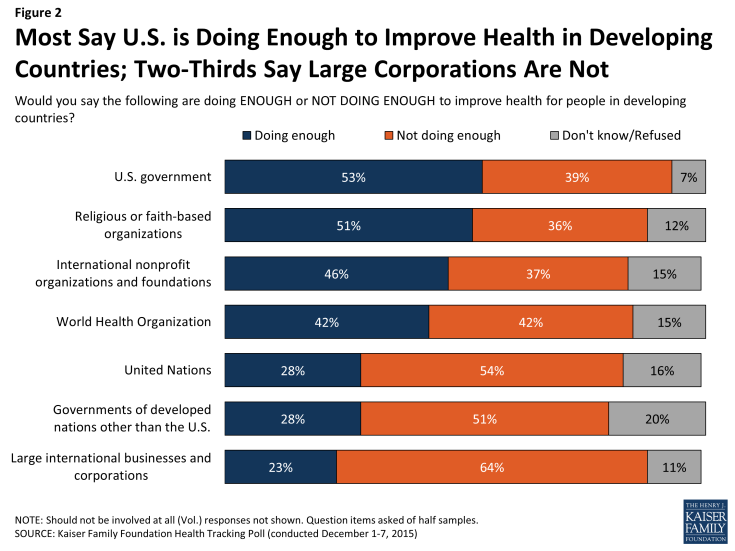

When it comes to global health issues specifically, a slim majority of Americans (53 percent) say the U.S. government is doing enough to improve health for people in developing countries, while four in ten (39 percent) say that it is not doing enough. In addition, half (51 percent) also say religious or faith-based organizations are doing enough and a similar share (46 percent) say the same about international nonprofit organizations. Americans are split on their opinion of the World Health Organization (WHO), the public health arm of the United Nations, with equal shares saying the WHO is doing enough and not doing enough (42 percent each).

On the other hand, majorities say that large international businesses and corporations (64 percent), the United Nations (54 percent), and the governments of other developed countries (51 percent) are not doing enough to improve health for people in developing countries.

Figure 2: Most Say U.S. is Doing Enough to Improve Health in Developing Countries; Two-Thirds Say Large Corporations Are Not

Unlike the bipartisan support for U.S. involvement in world affairs generally, there is a substantial partisan divide in views of U.S. efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. Majorities of Republicans (68 percent) and independents (59 percent) say the U.S. government is doing enough in this area, while a slim majority of Democrats (52 percent) feel the opposite, saying the U.S. is not doing enough. The difference between Republicans and Democrats on views of whether the U.S. is doing enough has widened somewhat since 2009.

| Table 1: U.S. Government Doing Enough to Improve Health in Developing Countries | ||||

| Would you say the U.S. government is doing enough or not doing enough to improve health for people in developing countries? | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| Yes, doing enough | 53% | 38% | 59% | 68% |

| No, not doing enough | 39% | 52% | 36% | 24% |

| NOTE: Should not be involved (Vol.) and Don’t know/Refused not shown. | ||||

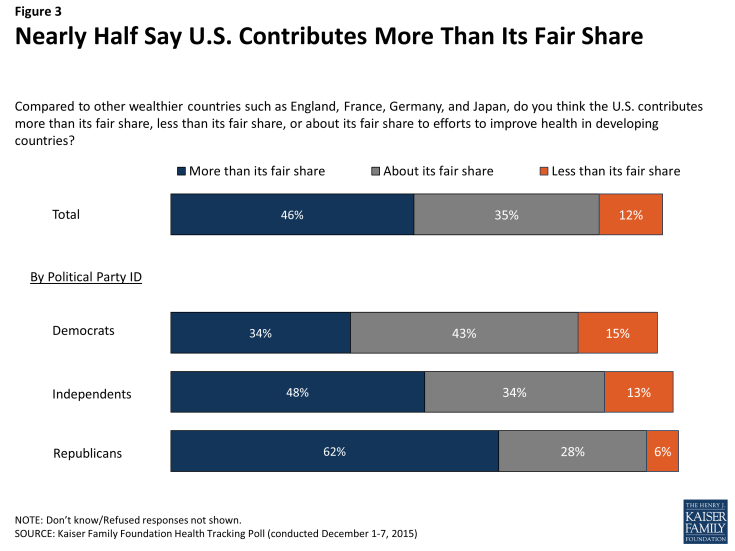

Echoing the sentiment of about half of Americans who say the U.S. government is doing enough to improve the health of those in developing countries, nearly half (46 percent) say that the U.S. is doing more than its fair share compared to other wealthy countries, such as England, France, Germany and Japan. About a third (35 percent) say the U.S. contributes about its fair share, and 12 percent say the U.S. contributes less than its fair share. Again, there are partisan differences, with Republicans much more likely than Democrats to say that the U.S. is contributing more than its fair share (62 percent versus 34 percent). Here also, the difference in opinion between Republicans and Democrats has widened over the last few years, from a difference of 17 percentage points in 2012 to 28 percentage points currently.

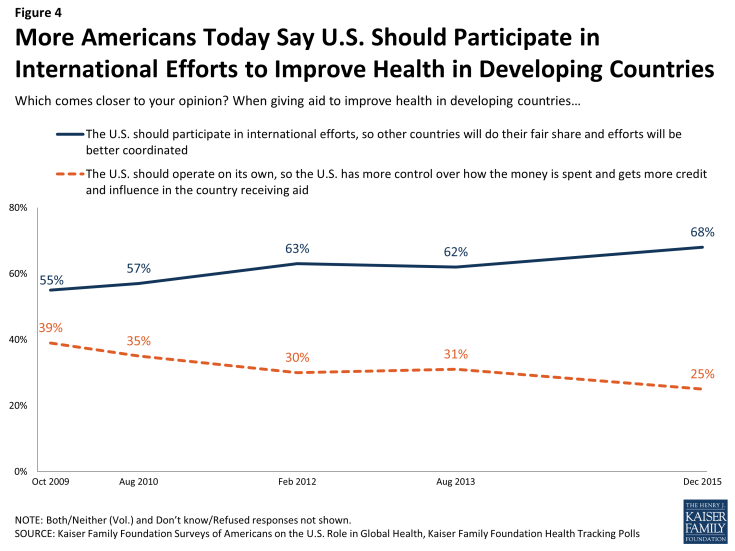

When it comes to U.S foreign aid aimed at improving health in developing countries, more Americans prefer a collaborative international approach over the U.S. acting alone in these efforts. Two-thirds of Americans (68 percent) prefer to see the country participate in international efforts so that other countries will do their fair share and efforts will be better coordinated. On the other side, a quarter (25 percent) say that the U.S. should operate on its own, allowing the government more control over how the money is spent and giving the U.S. more credit and influence in the country receiving aid. This gap has slowly widened over the past few years, with more Americans today saying that the U.S. should work alongside other countries than in 2009 (68 percent today versus 55 percent in 2009).

Figure 4: More Americans Today Say U.S. Should Participate in International Efforts to Improve Health in Developing Countries

Americans’ Views on U.S. Global Health Spending

Most Overestimate U.S. Spending on Foreign Aid and Doubt Value Of Global Health Spending

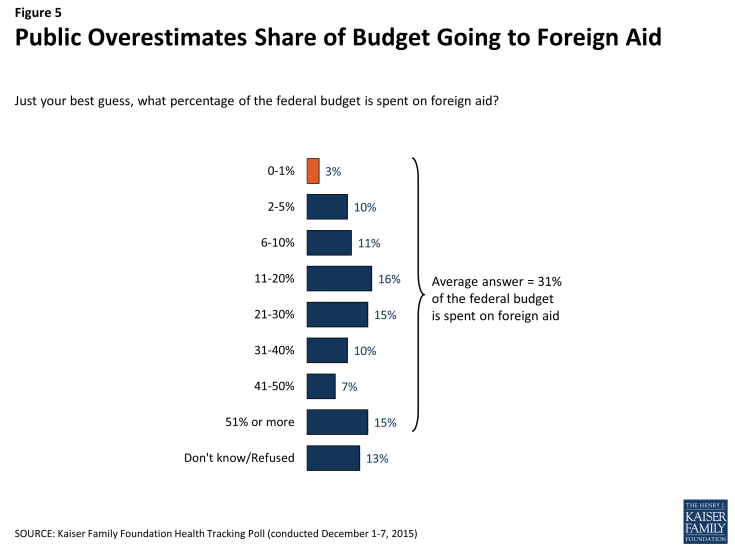

A large majority of the public overestimates the share of the federal budget that is spent on foreign aid. Just 3 percent of Americans correctly state that 1 percent or less of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid, and nearly half (47 percent) believe that share is greater than 20 percent. On average, Americans say spending on foreign aid makes up 31 percent of the federal budget.

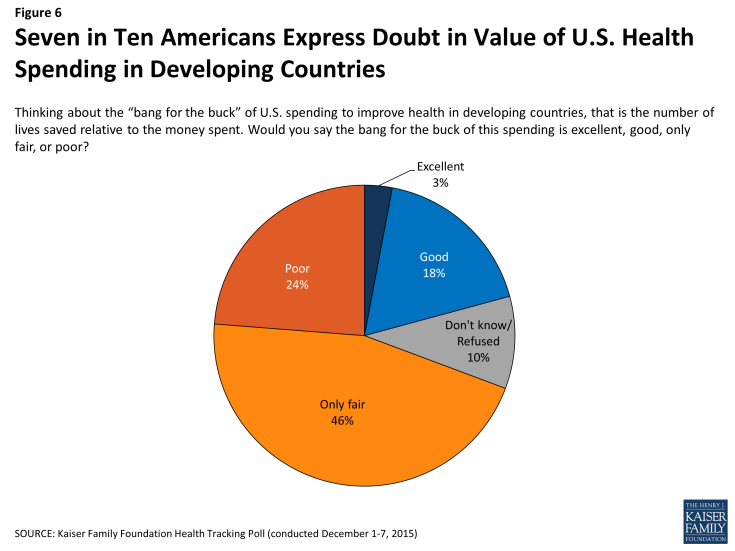

Among the public, critics of U.S. global health funding often point to the poor value or “bang for the buck” of spending aimed at improving health in developing countries, that is, the number of lives saved relative to the amount of money spent. A large majority of Americans (69 percent) express doubt in the value of global health spending, saying that the “bang for the buck” of these dollars is “only fair” or “poor.” On the other side, about one in five (21 percent) say the value is “excellent” or “good.” There are no substantial partisan differences, with a majority of Democrats, Republicans, and independents reporting that the value of spending is “only fair” or “poor.”

Figure 6: Seven in Ten Americans Express Doubt in Value of U.S. Health Spending in Developing Countries

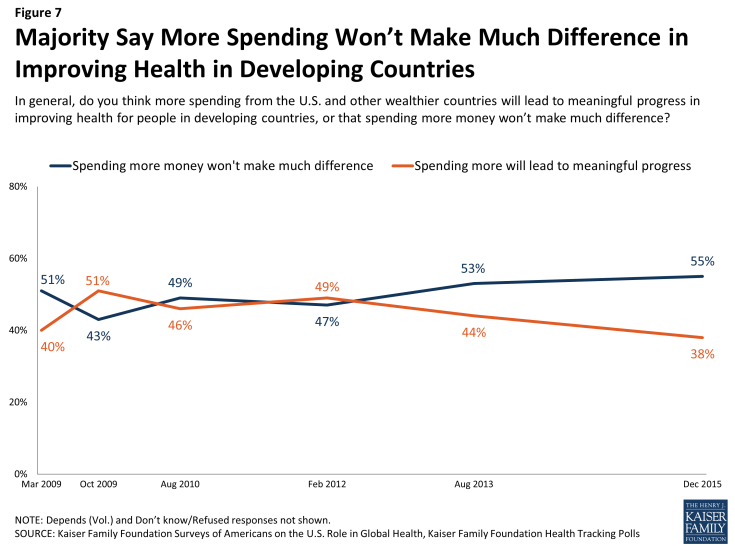

In addition, there is also doubt about the effectiveness of foreign aid from the U.S. and other wealthy nations, with more than half of Americans (55 percent) saying that spending more money will not lead to meaningful progress in improving health for people in developing countries. Still, about four in ten (38 percent) say that more spending on the part of the U.S. and other countries will lead to meaningful progress. This gap has widened somewhat since February 2012, when opinions regarding spending were more evenly divided. Republicans (67 percent) and independents (58 percent) are particularly skeptical, with majorities saying that more spending will not make much difference, compared to nearly four in ten Democrats (38 percent) who say the same. These partisan differences have increased over time, from a margin of 14 percentage points separating Republicans and Democrats who are doubtful that spending more will lead to meaningful progress in 2009, compared to a difference of 29 percentage points today.

Figure 7: Majority Say More Spending Won’t Make Much Difference in Improving Health in Developing Countries

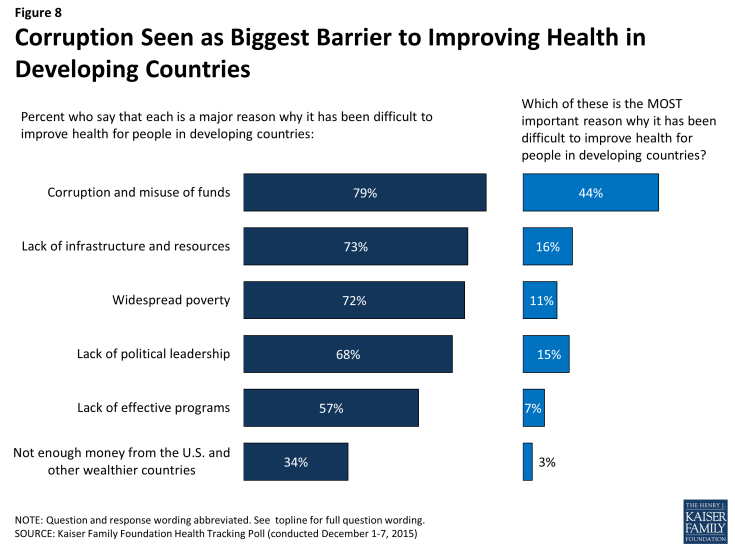

Related to the general skepticism towards U.S. global health spending, the American public sees a number of barriers to making progress improving health for people in developing countries. Eight in ten Americans (79 percent) point to corruption and misuse of funds as a major reason for such difficulties. Roughly seven in ten say issues such as lack of infrastructure and resources (73 percent), widespread poverty (72 percent) and lack of political leadership (68 percent) are major reasons for difficulty in improving health, and nearly six in ten (57 percent) cite a lack of effective programs. Many fewer – just about a third (34 percent) – say that a major reason is a lack of money from the U.S. and other wealthier countries.

Although Americans say there are several major reasons for the difficulty of improving health for people in the developing world, when asked which is the single most important reason, the largest share (44 percent) name corruption and misuse of funds, while much smaller shares point to other issues, such as lack of infrastructure (16 percent) or lack of political leadership (15 percent).

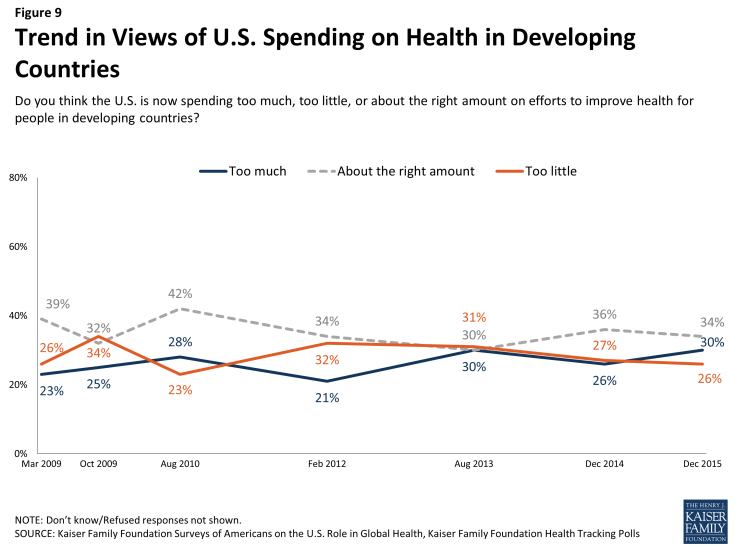

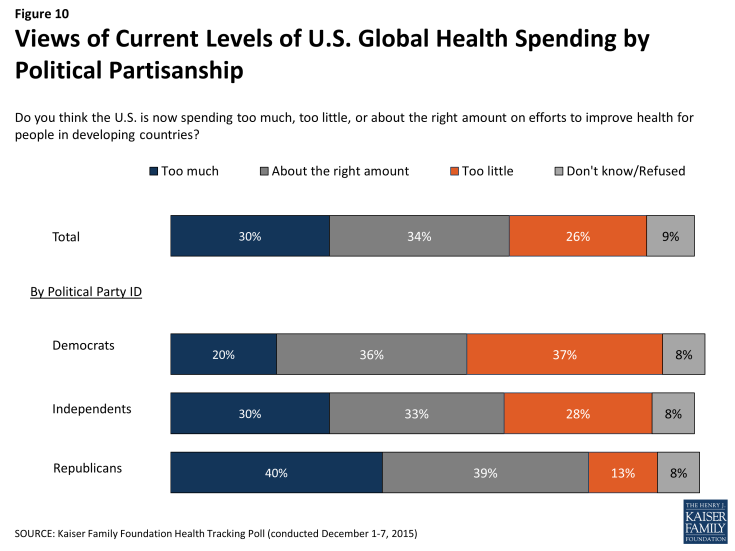

Although much of the public doubts the value and effectiveness of global health spending and points to several barriers to progress, 60 percent say the U.S. spends too little (26 percent) or about the right amount (34 percent) on global health, and 30 percent say it spends too much. This is similar to previous Kaiser polls over the past several years.

More Republicans say the U.S. spends too much on such global health spending than say it spends too little (40 percent versus 13 percent), while more Democrats say the U.S. spends too little, rather than too much (37 percent versus 20 percent). Independents are about evenly split, with about three in ten saying the U.S. spends too much (30 percent) or too little (28 percent). Still half or more of Republicans (52 percent), independents (61 percent) and Democrats (73 percent) say the U.S. is spending about the right amount or too little on efforts to improve global health.

Most Say U.S. Global Health Aid Helps Protect Americans’ Health and It’s the Right Thing To Do

While there is general skepticism about the effectiveness of global health spending, many Americans believe there are a number of benefits to spending money to improve health in developing countries. More than six in ten (63 percent) say that such spending helps protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases like SARS, bird flu, swine flu, and Ebola and about half say it helps make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient (53 percent) and helps improve the U.S. image around the world (52 percent). Fewer Americans, however, say U.S. health spending in developing countries benefits the U.S. economy (33 percent) or helps U.S. national security by lessening the threat of terrorism (31 percent), while about two-thirds of the public thinks it does not have much impact in those areas.

Democrats are generally more likely than Republicans and independents to say that spending money on improving health in developing countries has such impacts, but still about six in ten Republicans and independents say it helps protect Americans’ health (58 percent and 62 percent, respectively).

| Table 2: Impact of Global Health Spending | ||||

| Percent who say spending money on improving health in developing countries helps… | Total | Democrats | Independents | Republicans |

| …Protect the health of Americans by preventing the spread of diseases like SARS, bird flu, swine flu, and Ebola | 63% | 73% | 62% | 58% |

| …Make people and communities in developing countries more self-sufficient | 53 | 65 | 49 | 43 |

| …Improve the U.S. image around the world | 52 | 64 | 51 | 42 |

| …The U.S. economy by improving the circumstances of people who can buy more U.S. goods | 33 | 41 | 30 | 27 |

| …U.S. national security by lessening the threat of terrorism originating in developing countries | 31 | 39 | 34 | 18 |

Although many acknowledge there are domestic interests that could benefit from global health aid, nearly half of Americans (46 percent) say that the most important reason that the U.S. spends money on improving health for people in developing countries is because it’s the right thing to do. This ranks far above other reasons, such as ensuring national security (14 percent), improving our diplomatic relationships (14 percent), helping the U.S. economy by creating new markets for U.S. businesses (11 percent), or improving the U.S.’s image around the world (9 percent). Americans’ views of the reasons for such spending do not vary by political party.

Moving Forward: U.S. Preparedness and U.N. Sustainable Development Goals

Most say Disease Outbreak Is Likely in Next 5 Years, But U.S. Is Well-Prepared

Most Americans say that another Ebola outbreak – or an outbreak of an equally serious disease – is likely in the next five years, but many also express confidence in U.S. preparedness in handling such an outbreak. A large majority of Americans (83 percent) say that another serious Ebola outbreak in Africa in the next five years is at least somewhat likely. About as many (87 percent) say it is at least somewhat likely that there will be an outbreak of a different disease, but one that is equally as serious as Ebola.

Although many Americans expect another outbreak, when asked how prepared the U.S. government is to respond to future disease outbreaks around the world, two-thirds overall (66 percent) say the U.S. is at least somewhat well-prepared, including 16 percent who say the country is “very well-prepared.” However, about a third (32 percent) say the U.S. government is not well-prepared. There are no substantial differences between political partisans on U.S. preparedness on this issue.

Figure 12: Large Majority Say Ebola or Other Serious Disease Outbreak Likely in the Next Five Years, Many Say U.S. is Well-Prepared

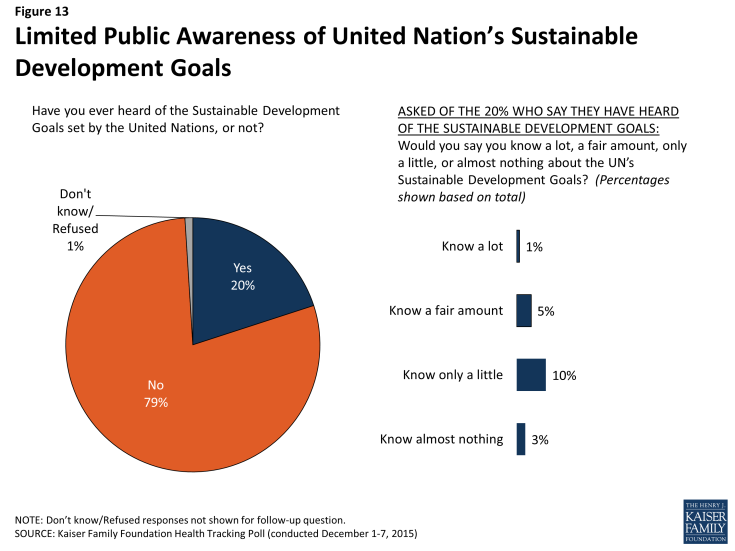

Limited Awareness of United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals

Global health leaders often point to the recent adoption of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as an important multinational initiative for progress in improving health and development globally. These goals focus on economic and human development and the eradication of poverty and are meant to guide all global development efforts, including global health efforts, through 2030. However, a large majority of Americans (79 percent) say they haven’t heard of them. Only one in five (20 percent) say they have heard of these goals, including 6 percent who say they know a “fair amount” or “a lot” about them and 13 percent who say they know “only a little” or “almost nothing.”