Medicare and Telehealth: Coverage and Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Options for the Future

Issue Brief

Introduction

Telehealth, the provision of health care services to patients from providers who are not at the same location, has experienced a rapid escalation in use during the COVID-19 pandemic, among both privately-insured patients and Medicare beneficiaries. Before the pandemic, coverage of telehealth services under traditional Medicare was limited to beneficiaries living in rural areas only, with restrictions on where beneficiaries could receive these services and which providers could be paid to deliver them. Soon after the federal government declared a public health emergency due to COVID-19 in early 2020, Congress and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expanded traditional Medicare’s coverage of telehealth services in order to make it easier for beneficiaries to get medical care and minimize their exposure to coronavirus in health care settings. When the public health emergency ends, however, Medicare’s coverage of telehealth services will revert back to the more limited availability that existed before the pandemic, unless policymakers take action to extend the expanded coverage.

In light of the rapid, but time-limited, expansion of telehealth coverage under traditional Medicare, this brief provides an overview of the changes made during the COVID-19 pandemic to Medicare’s coverage of telehealth. It also presents new analysis of Medicare beneficiaries’ utilization of telehealth between the summer and fall of 2020, and discusses issues and questions related to extending telehealth coverage under traditional Medicare beyond the public health emergency. Our analysis of beneficiaries’ use of telehealth services is based on survey data of Medicare beneficiaries living in the community from the CMS Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Fall 2020 COVID-19 Supplement. All differences reported in the text are statistically significant, unless otherwise noted. (See Data and Methods for details.)

Key Findings

- Among the vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care (95%), such as a doctor or other health professional, or a clinic, nearly two-thirds (64% or 33.6 million) say that their provider currently offers telehealth appointments, up from 18% who said their provider offered telehealth before the pandemic. But nearly a quarter of Medicare beneficiaries (23%) say they don’t know if their provider offers telehealth appointments, and this percentage is larger among beneficiaries who live in rural areas (30%).

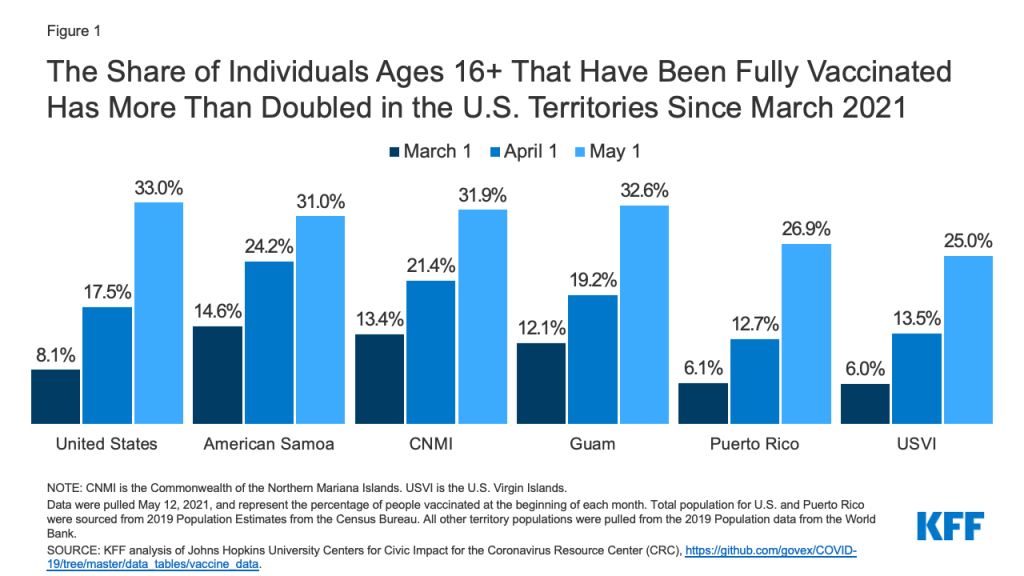

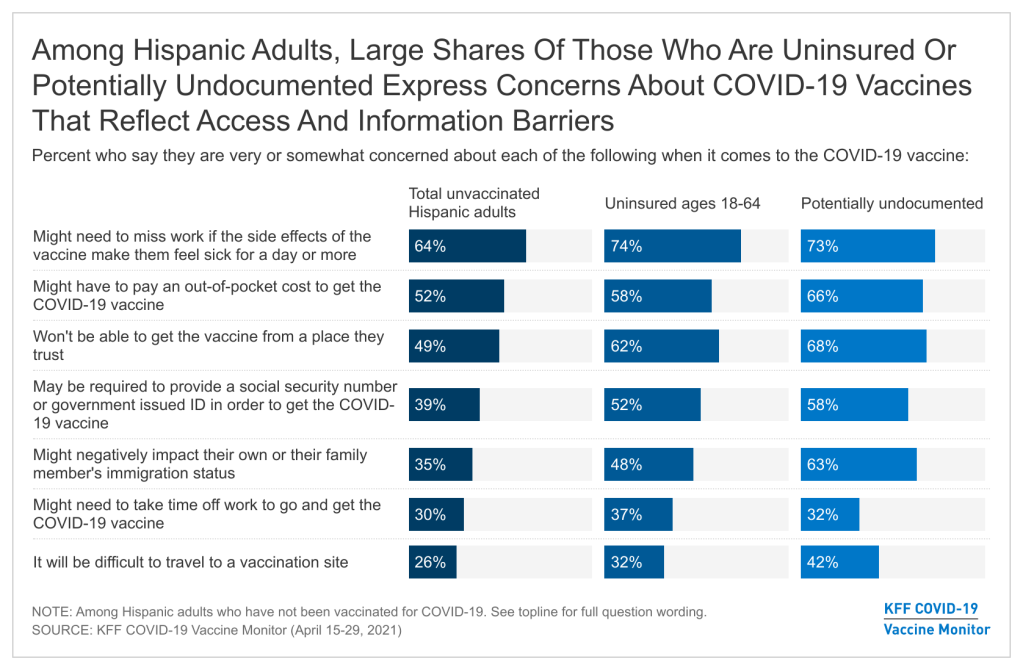

- Among the 33.6 million Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care who reported that their provider currently offers telehealth appointments, nearly half (45%) said they had a telehealth visit with a doctor or other health professional between the summer (July) and fall of 2020. This translates to just over 1 in 4 (27% or 15 million) of all community-dwelling beneficiaries in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage using telehealth during this time period (Figure 1).

- Reported telehealth use among beneficiaries who said their provider offers telehealth was higher among Medicare beneficiaries under the age of 65 who qualify for Medicare due to a long-term disability (53%), beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (55%), Black (52%) and Hispanic (52%) beneficiaries, and those with 6 or more chronic conditions (56%). For some groups, including Medicare-Medicaid enrollees and those with multiple chronic conditions, higher rates of telehealth use may be related to higher use of health care overall. There was no difference in reported rates of telehealth use between beneficiaries in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage (44% and 45%, respectively).

- Among Medicare beneficiaries who had a telehealth visit, a majority (56%) report accessing care using a telephone only, while a smaller share had a telehealth visit via video (28%) or both video and telephone (16%). The share of Medicare beneficiaries who had a telehealth visit using telephone only was higher among those age 75 and older (65%), Hispanic beneficiaries (61%), those living in rural areas (65%), and those enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (67%).

Background on Medicare Coverage of Telehealth and Changes under the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, coverage of telehealth services under traditional Medicare was limited. Medicare paid for approximately 100 services provided by telehealth, and there were limitations on how these services could be delivered and which beneficiaries could access them. Such limitations do not apply in Medicare Advantage plans, which have flexibility to offer additional telehealth benefits not covered by traditional Medicare outside of the public health emergency (see below for more information). Prior to the pandemic, the utilization of telehealth among traditional Medicare beneficiaries was extremely low, with only 0.3% of traditional Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part B using telehealth services in 2016, accounting for only 0.4% of traditional Medicare Part B spending. Similarly, analysis of primary care visits in traditional Medicare found that only 0.1% of these visits were provided via telehealth before the pandemic in February 2020.

To make it easier and safer for beneficiaries to seek medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic, the HHS Secretary waived certain restrictions on Medicare coverage of telehealth services for traditional Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 public health emergency, based on waiver authority included in the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act (and as amended by the CARES Act). The waiver, effective for services starting on March 6, 2020, significantly loosened coverage restrictions for telehealth under traditional Medicare during the public health emergency, as described below. The public health emergency was most recently renewed in April 2021, and, according to the Biden Administration, is expected to remain in place for the duration of 2021.

Which traditional Medicare beneficiaries can receive telehealth services and where?

Before the public health emergency, telehealth services were generally available only to beneficiaries in rural areas originating from a health care setting, such as a clinic or doctor’s office. Beneficiaries in urban areas were ineligible for telehealth services, and beneficiaries could not receive telehealth services in their own homes. During the public health emergency, beneficiaries in any geographic area can receive telehealth services, and can receive these services in their own home, rather than needing to travel to a “distant site” (i.e., a health care setting).

What technologies can traditional Medicare beneficiaries use to access telehealth services?

Under Medicare’s existing telehealth benefit, a telehealth visit must be conducted with two-way audio/video communications and the use of smartphones or audio-only telephones in lieu of video is not permitted. For the duration of the COVID-19 public health emergency, telehealth services can be conducted via an interactive audio-video system, as well as using smartphones with real-time audio/video interactive capabilities without other equipment. Additionally, a limited number of telehealth services can be provided to patients via audio-only telephone or a smartphone without video.

What type of providers can get reimbursed by Medicare for telehealth visits?

Before the public health emergency, only physicians and certain other practitioners (such as physician assistants, clinical social workers, and clinical psychologists) were eligible to receive Medicare payment for telehealth services provided to eligible beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, and they must have treated the beneficiary receiving the services in the last three years. During the public health emergency, any health care professional that is eligible to bill Medicare for professional services can provide and bill for telehealth services, and does not need to have previously treated the beneficiary. Also, federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics are allowed to provide telehealth services to Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 public health emergency; these settings were not authorized as providers of telehealth services for Medicare beneficiaries prior to the pandemic.

What services can traditional Medicare beneficiaries receive through telehealth?

Before the public health emergency, traditional Medicare covered about 100 services that could be administered through telehealth, including office visits, psychotherapy, and preventive health screenings, among other services. During the public health emergency, the list of allowable telehealth services covered under traditional Medicare expanded to include emergency department visits, physical and occupational therapy, and certain other services. Some evaluation and management, behavioral health, and patient education services can be provided to patients via audio-only telephone.

Are there additional services, other than telehealth, that are delivered virtually and covered by traditional Medicare?

Separate from Medicare’s coverage of telehealth services, traditional Medicare covers brief, “virtual check-ins” (also called “brief communication technology-based services”) via telephone or captured video image, and E-visits for all beneficiaries, regardless of whether they live in a rural area. Both of these services, which were not amended during the public health emergency, are more limited in scope than a full telehealth visit. For example, virtual check-ins can only be reported by providers with an established relationship to the patient, cannot be related to a recent medical visit (within the past 7 days), and cannot lead to a medical visit in the next 24 hours (or the soonest available appointment, and payment is intended to cover only 5-10 minutes of medical discussion.

How does Medicare pay providers for telehealth services?

Before the public health emergency, Medicare’s payment for a telehealth service was the same regardless of whether it was provided in a non-facility setting, such as a clinician’s office, or a facility setting, such as a hospital outpatient department, and the payment rate was based on the lower amount paid to facility-based providers for a service delivered in person. (Under Medicare’s physician fee schedule, the payment to facility-based-providers for in-person services is lower than the payment to non-facility providers because Medicare makes a separate payment to facilities to cover practice expenses, such as physical space, medical supplies, medical equipment, and clinical staff time.) The rationale for using the lower facility payment amount for telehealth services was that practice expenses for the delivery of telehealth services should be lower than those for an in-person visit.

During the public health emergency, Medicare pays for telehealth services, including those delivered via audio-only telephone, as if they were administered in person, with the payment rate varying based on the location of the provider, which means that Medicare pays more for a telehealth service provided by a doctor in a non-facility setting than by a doctor in a hospital outpatient department. This also means that during the public health emergency, doctors in non-facility settings are receiving a higher payment for services provided by telehealth than they did before the public health emergency.

What do traditional Medicare beneficiaries pay for telehealth services?

Beneficiary cost sharing for telehealth services has not changed during the public health emergency. Medicare covers telehealth services under Part B, so beneficiaries in traditional Medicare who use these benefits are subject to the Part B deductible of $203 in 2021 and 20% coinsurance. However, the HHS Office of Inspector General has provided flexibility for providers to reduce or waive cost sharing for telehealth visits during the COVID-19 public health emergency, although there is no publicly-available data to indicate the extent to which providers may have done so. Most beneficiaries in traditional Medicare have supplemental insurance that may pay some or all of the cost sharing for covered telehealth services.

How is telehealth covered under Medicare for beneficiaries and providers participating in alternative payment modes?

Separate from the time-limited expanded availability of telehealth services, CMS has granted providers participating in some alternative payments models, including Next Generation accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare Shared Savings Program ACOs, greater flexibility to provide care through telehealth, including billing for telehealth services provided to both urban and rural beneficiaries and to beneficiaries when they are at home. Telehealth flexibilities in the Next Generation ACO demonstration are granted via benefit enhancement waivers administered by CMS. From 2016-2018, few Next Generation ACOs received and implemented telehealth waivers (4 ACOs; 8% of all ACOs in the model).

How does coverage of telehealth services differ in Medicare Advantage?

Medicare Advantage plans have been able to offer additional telehealth benefits not covered by traditional Medicare outside of the public health emergency, including telehealth visits provided to enrollees in their own homes and services provided outside of rural areas. In 2021, virtually all Medicare Advantage plans (98%) offer a telehealth benefit.

Medicare Advantage plans are paid a capitated amount by Medicare to provide basic Medicare benefits covered under Parts A and B; legislative changes implemented in 2020 allow plans to include additional telehealth benefits beyond what traditional Medicare covers in their bids for basic benefits. Therefore, the cost of additional telehealth services offered by Medicare Advantage plans are reflected in the capitated payment that plans receive.

Medicare Advantage plans have flexibility to waive certain requirements with regard to coverage and cost sharing in cases of disaster or emergency, such as the COVID-19 outbreak. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, CMS has advised plans that they may waive or reduce cost sharing for telehealth services, as long as plans do this uniformly for all similarly situated enrollees. Many Medicare Advantage plans have waived or reduced cost sharing for enrollees for some or all services administered via telehealth during the public health emergency.

Who Has Used Telehealth Services During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency?

Awareness of Telehealth Availability

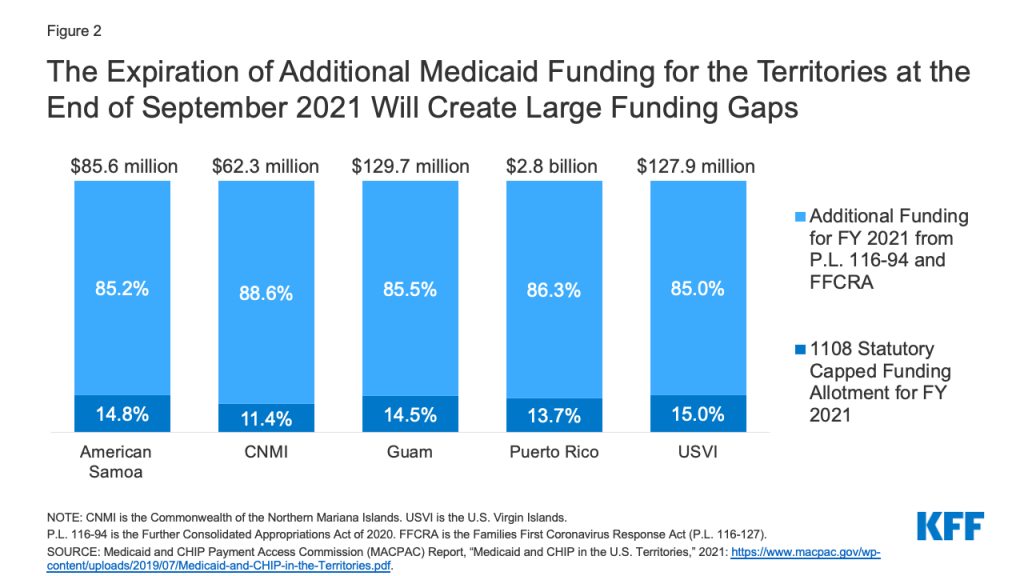

As of Fall 2020, six months after the expansion of telehealth benefits in traditional Medicare for the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly two-thirds of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries who say they have a usual source of care (64%, or 33.6 million beneficiaries), such as a doctor or health professional, or a clinic, reported that their usual provider offers telehealth appointments, up from roughly 1 in 5 (18%, or 6.1 million) beneficiaries who said their usual provider offered telehealth before the pandemic (Figure 2; Table 1). (The majority of community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries, 95% or 52.7 million, report having a usual source of care). Conversely, 13% of beneficiaries with a usual source of care said their provider does not currently offer telehealth, a substantial decrease compared to the 52% who said their provider did not offer telehealth before the COVID-19 pandemic.

While the reported availability of telehealth has increased during the pandemic, nearly a quarter of Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care (23% or 11.9 million beneficiaries) said they do not know if their usual provider currently offers telehealth appointments.

The reported rates of beneficiaries who say their provider currently offers telehealth was similar across most demographic groups (Figure 3). However, a smaller share of Medicare beneficiaries living in rural areas than those living in urban areas said their provider currently offers telehealth (52% vs. 67%, respectively), and a larger share of rural beneficiaries report not knowing if their usual provider offers telehealth appointments than beneficiaries living in urban areas (30% vs 21%, respectively).

A larger share of Black Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care (23%) say their usual provider does not currently offer telehealth appointments than White (12%) and Hispanic (15%) beneficiaries with a usual source of care. Additionally, a larger share of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (19%) say their usual provider does not currently offer telehealth appointments than Medicare beneficiaries who are not enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (12%).

Use of Telehealth

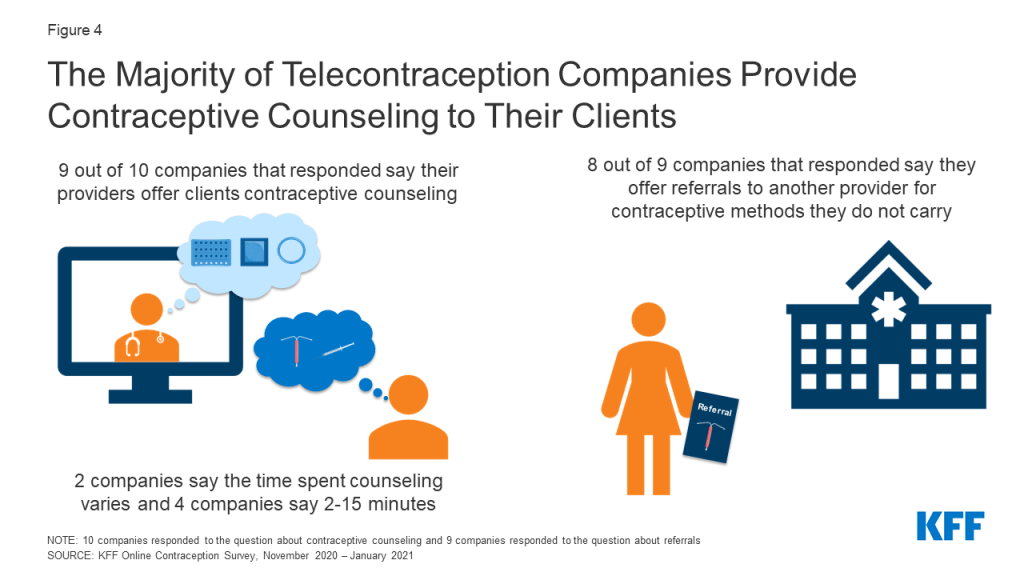

Among the two-thirds of Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care who reported in the Fall of 2020 that their usual provider offers telehealth during the pandemic (33.6 million beneficiaries), nearly half (45%, or 14.9 million beneficiaries) reported having a telehealth visit since July 2020. Some groups of Medicare beneficiaries were more likely than others to report having a telehealth visit with a doctor or other health professional since July 2020, including Medicare beneficiaries under age 65 with long-term disabilities, Black and Hispanic beneficiaries, Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid, and beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions (Figure 4; Table 2).

Among Medicare beneficiaries who have a usual source of care and whose usual provider offers telehealth:

- More than half (53%) of beneficiaries under the age of 65 (who qualify for Medicare due to a long-term disability) had a telehealth visit, compared to 42% of those age 65 to 74 and 43% of those age 75 or older.

- A larger share of Black (52%) and Hispanic (52%) Medicare beneficiaries than White (43%) beneficiaries say they had a telehealth visit.

- More than half (55%) of beneficiaries enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid had a telehealth visit, compared to 43% of Medicare beneficiaries not enrolled in Medicaid.

- A larger share of beneficiaries with 6 or more chronic conditions reported having a telehealth visit than those with zero or 1 chronic condition (56% vs. 33%), and half or more of Medicare beneficiaries with specific chronic conditions had a telehealth visit, including those with diabetes (50%), a heart condition (50%), emphysema, asthma, or COPD (54%), and depression (55%), and those who are immunocompromised (59%).

- A similar share of Medicare Advantage enrollees and beneficiaries in traditional Medicare had a telehealth visit since July 2020 (45% and 44%, respectively) (Table 2).

- Medicare beneficiaries who report having a telehealth visit between the summer and fall of 2020 account for 1 out of 4 Medicare beneficiaries overall (27%, or 14.9 million beneficiaries), based on the total population of community-dwelling beneficiaries, which also includes beneficiaries who said they did not have a telehealth visit, beneficiaries who do not know if their provider offers telehealth, and those without a usual source of care who were not asked about their use of telehealth (Figure 4, Table 2).

Notably, among Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care and whose usual provider offers telehealth, we found no significant difference between the share of rural and urban Medicare beneficiaries who had a telehealth visit (43% and 45%, respectively). However, based on the overall population in these groups, rural Medicare beneficiaries were less likely than urban beneficiaries to have a telehealth visit with a doctor or other health professional (21% vs. 28%, respectively). This difference is likely driven by the fact that rural Medicare beneficiaries were more likely than urban Medicare beneficiaries to say they do not know if their usual provider offers telehealth (30% vs. 21%, respectively).

Similarly, among Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care whose usual provider offers telehealth, we found that a larger share of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries had a telehealth visit compared to White beneficiaries (52%, 52%, and 43%). However, among the total Medicare population, the difference in the share of Black and White beneficiaries who reported having a telehealth visit was not statistically significant (30% vs. 26%), while a larger share of Hispanic beneficiaries than White beneficiaries had a telehealth visit (33% vs. 26%). For Black Medicare beneficiaries, this result is likely related to the fact that nearly a quarter of Black beneficiaries overall (23%) say their usual provider does not offer telehealth appointments, compared to 12% of White beneficiaries and 15% of Hispanic beneficiaries.

How Did Beneficiaries Access Telehealth Services?

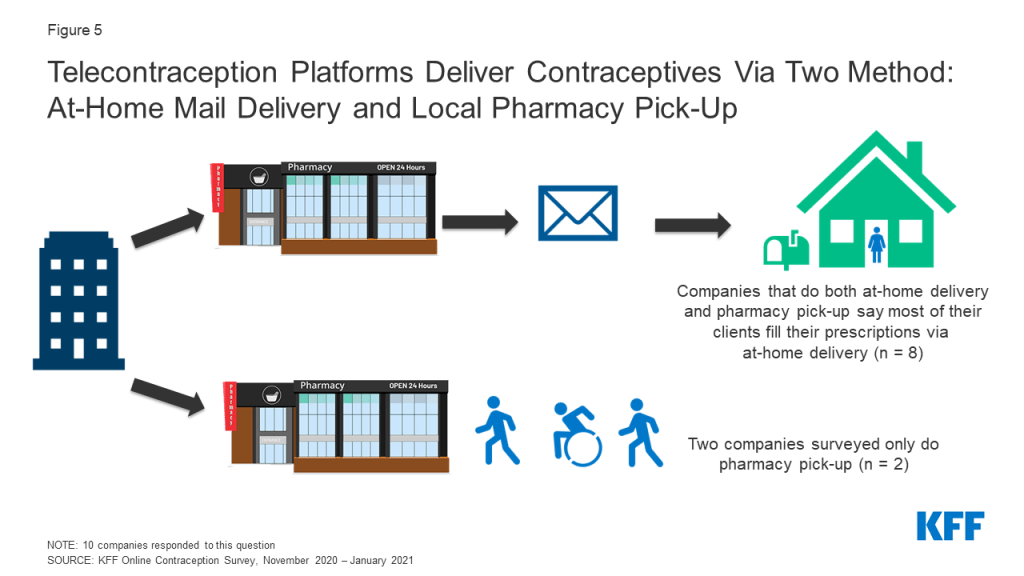

Among Medicare beneficiaries with a usual source of care whose provider offers telehealth appointments, the majority of those who had a telehealth visit since July 2020 accessed the service by telephone (56%), compared to 28% who reported having a telehealth visit by video and 16% who used both telephone and video (Figure 5; Table 3). This may be related to the fact that while more than 8 in 10 Medicare beneficiaries report having access to the internet (83%), smaller shares say they own a computer (64%) or a smartphone (70%) (Figure 6, Table 4).

–

There are notable differences by demographic characteristics in how beneficiaries have accessed telehealth services during the pandemic and the availability of technology that enables access to telehealth, for example:

- Two thirds (65%) of beneficiaries 75 and older had a telehealth visit that was telephone-only compared to just over half (52%) of those ages 65 to 74, findings that likely reflect the smaller share of Medicare beneficiaries age 75 and older who report having access to the internet compared to those ages 65 to 74 (74% vs. 89%), or owning a computer (56% vs. 74%) or smartphone (53% vs. 80%).

- Six in 10 (61%) Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries had a telehealth visit that was telephone-only, compared to 54% of White beneficiaries, likely related to the fact that a smaller share of Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries than White beneficiaries report having access to the internet (67% vs. 86%), and a much smaller share of Hispanic beneficiaries than White beneficiaries say they own a computer (34% vs. 71%). Similarly, just 42% of Black Medicare beneficiaries own a computer, compared to 71% of those who are White, but the difference in the share of beneficiaries reporting a telephone-only telehealth visit was not significantly different for Black and White beneficiaries.

- Beneficiaries who live in rural areas were more likely than those living in urban areas to report having a telehealth visit that was telephone-only (65% vs. 54%), likely reflecting lower rates of internet access for rural beneficiaries than urban beneficiaries (78% vs. 84%) and ownership of computers (58% vs. 66%) or smartphones (60% vs. 72%).

Looking to the Future: Expanding Medicare Coverage of Telehealth Beyond the Pandemic

Our analysis finds that 1 in 4 Medicare beneficiaries have had a telehealth visit during the COVID-19 public health emergency, representing a substantial increase in use since before the pandemic. Our finding that, among beneficiaries whose provider offers telehealth, a greater share of those with disabilities, with low incomes, and in communities of color have used telehealth suggests that the temporary expansion of telehealth coverage may be helping some of Medicare’s more disadvantaged populations continue to access needed care. At the same time, in light of our finding that a quarter of Medicare beneficiaries overall (and an even larger share of those in rural areas) do not know if their doctor currently offers telehealth, efforts to increase awareness of covered telehealth services under Medicare during the public health emergency could help to broaden its reach.

Currently, policymakers are considering a variety of proposals to expand some or all of the existing flexibilities surrounding telehealth services under Medicare beyond the public health emergency, and many have expressed support for doing so. Among the telehealth-related bills that have been introduced in the 117th Congress include proposals to permanently cover some of the telehealth expansions provided during the public health emergency, expand Medicare-covered mental health services and evaluation and management services administered via telehealth, and expand the scope of providers eligible for payment for telehealth services covered by Medicare. Other bills are aimed at assessing the impact of expanded telehealth services on the quality of patient care and program spending.

Under Medicare’s existing telehealth benefit, a telehealth visit must be conducted with two-way audio/video technology, while under the current public health emergency waiver, a limited number of telehealth services can be provided to patients via audio-only telephone. Given that the majority of Medicare beneficiaries in our analysis reported accessing telehealth services by telephone only, an expanded telehealth benefit that requires two-way video communication could be a barrier to care for subgroups of the Medicare population that relied more heavily on telephones than video-capable devices during the pandemic.

MedPAC has recommended that Medicare continue a modified version of expanded telehealth coverage for another year or two after the public health emergency ends, giving Medicare time to assess the effects of telehealth use on total costs, access, and quality of care. During this additional time, MedPAC recommends that Medicare pay for specified telehealth services regardless of where a beneficiary lives; cover some additional telehealth services beyond those covered prior to the public health emergency if there is potential for clinical benefit; and cover audio-only telehealth visits if there is potential for clinical benefit. MedPAC has also recommended that payment for telehealth services after the public health emergency revert to the lower facility-based payment rate in effect before the pandemic, and that providers should not be allowed to waive or reduce beneficiary cost sharing.

Expanded coverage of telehealth beyond the public health emergency could affect the quality of patient care as well as program and beneficiary spending. Broadening telehealth coverage has the potential to improve access to needed care, but there is uncertainty as to whether it would lead to an overall increase or decrease in program spending. Some telehealth services may be substitutes for in-person care, such as a behavioral health care visit, though easier access to telehealth could lead to an overall increase in visits and costs. Other telehealth services may not fully replace the need for (or occurrence of) an in-person visit, such as a visit to evaluate a skin rash or where lab work is determined to be needed. In building evidence on the cost and quality impacts of telehealth use in Medicare, the Administration could also potentially gain insights based on telehealth use by enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans, or by testing different approaches through Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation models.

The potential expansion of telehealth coverage brings with it concerns about the potential for fraudulent activity. There have been several large fraud cases involving telehealth companies in recent years, most of which involved the submission of fraudulent claims for items, services, and tests to Medicare and other insurers that were never given or administered to patients. HHS’ Office of the Inspector General (OIG) is conducting several studies to assess the appropriateness of use of telehealth during the public health emergency, including an analysis of provider billing patterns in order to identify providers that could pose a risk for program integrity and an audit of telehealth services under Part B to assure that services are meeting Medicare requirements. MedPAC has recommended that Medicare apply additional scrutiny to outlier clinicians who deliver more telehealth services than others, as well as requiring in-person visits before clinicians can order high-cost equipment or services for beneficiaries.

The temporary expansion of coverage for telehealth services has allowed many people with Medicare to access medical care during the coronavirus pandemic. Given that the temporary waiver of restrictions on coverage of telehealth services under Medicare will come to an end with the expiration of the public health emergency, the question of whether and how to ensure continued access to these services, while balancing concerns about quality of care and spending, looms large.

Data and Methods

This analysis uses survey data for community-dwelling Medicare beneficiaries from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) Fall 2020 COVID-19 Community Supplement. The MCBS Fall COVID-19 supplement includes several survey questions designed to assess Medicare beneficiaries’ access to care and use of telehealth services from July 2020 through Fall 2020.

In order to determine the share of Medicare beneficiaries whose provider offers telehealth, beneficiaries who answered affirmatively to the question “Is there a particular doctor or other health professional, or a clinic you usually go to when you are sick or for advice about your health?” (9,216 out of 9,686 respondents) were asked “Does your usual provider offer telephone or video appointments, so that you don’t need to physically visit their office or facility?” (5,644 respondents answered affirmatively).

In order to determine the share of Medicare beneficiaries who had a telehealth visit, beneficiaries with a usual source of care whose usual provider offers telehealth appointments were asked “Since July 1, 2020, have you had an appointment with a doctor or other health professional by telephone or video?” (2,515 respondents answered affirmatively). Similarly, beneficiaries with a usual source of care whose provider offers telehealth were asked “Did your usual provider offer telephone or video appointments before the coronavirus pandemic?” (1,035 respondents answered affirmatively).

To determine how beneficiaries accessed telehealth appointments, beneficiaries who had a telehealth appointment since July 2020 were asked “Was it a telephone appointment, video appointment, or both?” The majority of Medicare beneficiaries who had a telehealth visit since July 2020 had a visit via telephone (n=1,460), while fewer had a telehealth visit via video (n=653) or via both telephone and video (n=393).

Based on the questionnaire skip patterns, beneficiaries were only asked about their use of telehealth if they answered affirmatively that they had a usual source of care and that their usual provider offers telehealth. In order to determine the share of Medicare beneficiaries who had a telehealth visit among Medicare beneficiaries overall, we created a categorical variable that included beneficiaries whose provider did not offer telehealth or it was unknown. The variable had three categories: 1) usual provider offers telehealth and beneficiary had a telehealth visit (n=2,515); 2) usual provider offers telehealth and beneficiary did not have a telehealth visit (n=3,074); 3) usual provider does not offer telehealth or it was unknown (n=4,097).

Results from all statistical tests were reported with p<0.05 considered statistically significant.

Tables

–

–

–

–