How Do CMS’s New COVID-19 Vaccine Reporting and Education Rules Apply To Different Long-Term Care Settings?

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in substantial cases and deaths among long-term care facility (LTCF) residents and staff, though these numbers dropped precipitously after vaccine rollout began. As of May 17th, 2021, the US has reported over 184,000 COVID-19 deaths among LTCF residents and staff, accounting for nearly one-third of all COVID-19 deaths in the US. These data do not reflect the full extent of COVID-19’s impact on LTCFs beyond nursing homes, however, as data gaps for settings serving nonelderly people with disabilities are an ongoing challenge. Settings for which data are incomplete include certain institutions, such as intermediate care facilities for people with intellectual or developmental disabilities (ICF/IIDs) and inpatient behavioral health settings, and congregate community-based settings, such as group homes, personal care homes, assisted living facilities (ALFs), and adult day programs.

In addition to incomplete data, COVID-19 vaccine access and distribution efforts have varied across LTCF setting types. While the CDC’s Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care facilitated the initial vaccination of residents and staff at most nursing homes and ALFs, other LTCF types were ineligible for the Partnership. Moreover, now that the Partnership has ended, CMS estimates that the number of new residents and staff entering nursing homes and ALFs over the next year is expected to exceed the number of those that were offered a vaccine through the Partnership.

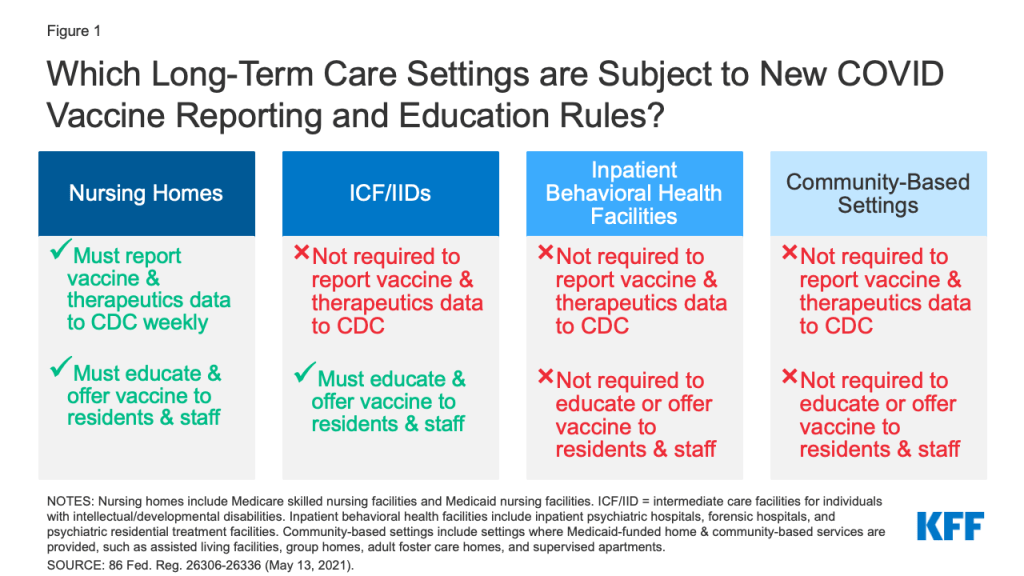

Recognizing that ongoing vaccination efforts are crucial to ending the pandemic, CMS issued an Interim Final Rule with Comment Period (IFC) that establishes new vaccine reporting and/or education requirements for nursing homes and ICF/IIDs as of May 21st, 2021. Public comments are due July 12, 2021, after which CMS may revise the rule. CMS also seeks public comment about whether similar requirements should apply to inpatient behavioral health settings and community-based congregate settings. This issue brief explains the new requirements and identifies where gaps remain across different LTCF settings (Figure 1). The Appendix provides detail about the various types of LTCFs.

What are the new reporting requirements for LTCFs?

Under the new interim final rule, nursing homes must report weekly on the COVID-19 vaccination status of all residents and staff as well as COVID-19 therapeutic treatment administered to residents. These requirements apply to both Medicare skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) and Medicaid nursing facilities (NFs). The new vaccine data elements must be reported to the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) and include the total numbers of residents and staff, numbers of residents and staff vaccinated, numbers of each dose of COVID-19 vaccine received, and COVID-19 vaccination adverse events. As with other Medicare and Medicaid conditions of participation, nursing homes that fail to follow the new reporting requirements may have to pay a civil monetary penalty.

The new interim final rule does not mandate COVID-19 vaccination or treatment reporting for other LTCF types. CMS concluded that requiring ICF/IIDs to participate in mandatory vaccine reporting would create an administrative burden, as very few (only about 80 out of over 5,700) currently participate in the NHSN or another formal reporting program, and requiring participation could involve new equipment, staff, and training. CMS also notes that ICF/IIDs do not appear to be administering COVID-19 therapeutics at this time. The new reporting requirements also do not apply to other LTCFs, such as inpatient behavioral health settings or congregate community-based settings. For all of these settings, CMS encourages voluntary reporting as facilities are able to do so and seeks comment on reporting barriers and ways to encourage voluntary reporting. Another rule that requires CDC reporting on COVID-19 cases and deaths applies only to nursing homes and not to other LTCF types.

What are the new vaccine education and offering requirements for LTCFs?

The new interim final rule’s requirements to educate residents/clients and staff about the COVID-19 vaccine and offer the vaccine when available apply more broadly, to both nursing homes and ICF/IIDs. CMS notes that these new requirements build on existing regulations that govern influenza and pneumonia immunizations for nursing homes and preventive care including immunizations for ICF/IIDs. In the preamble, CMS clarifies that staff who must be educated about and offered the vaccine include those who work in the facility at least once a week. Facilities must maintain documentation on their vaccine education efforts, administration of multi-dose vaccines, and efforts to appropriately acquire subsequent doses as necessary for all residents/clients and staff. As with other Medicare/Medicaid conditions of participation, facilities may be subject to civil money penalties if they fail to comply with the new requirements.

Under the new rule, nursing home and ICF/IID vaccine education efforts must include the benefits, risks, and potential side effects of the vaccine and the most current information regarding additional doses. In the preamble, CMS notes that facilities may choose to include other staff education topics, such as further information on the development of the vaccine, how the vaccine works, particulars of the multiple doses, and the low likelihood of potential side effects. The preamble also states that residents/clients and their representatives should be told that they are able to receive the vaccine without copays or out-of-pocket costs. Finally, CMS reminds facilities that educational materials should be made available in accessible formats, such as large print, Braille, American Sign Language, closed captioning, audio descriptions, and plain language.

The new rule requires nursing homes and ICF/IIDs to offer the COVID-19 vaccine to all residents/clients and staff unless immunization is medically contraindicated or they have already been immunized. The rule specifies that residents/clients and staff may refuse the vaccine and may change their decision at any time. Recognizing that decisions about whether to receive the vaccine may change over time, the preamble notes that if an individual requests a vaccine but missed earlier opportunities for any reason, facilities should try to acquire a vaccination opportunity for that individual “as quickly as practicable.” In the preamble, CMS clarifies that facilities may provide the vaccine directly or arrange for vaccination through another provider, such as a pharmacy or health department.

How are other congregate care settings addressed?

CMS is not requiring other LTCFs, such as inpatient behavioral health settings and congregate community-based settings, to report on COVID-19 vaccination, provide education, or offer the vaccine to residents and staff at this time. CMS notes that individuals in psychiatric facilities may only be inpatients for short periods, making a two-dose vaccine series challenging to administer, and CMS currently is unable to guarantee availability of the single-dose vaccine for these facilities. To facilitate vaccination for residents/clients and staff of congregate community-based settings, such as ALFs, group homes, and adult day centers, CMS encourages collaboration between these settings and state Medicaid agencies and state and local health departments to learn about vaccine distribution options.

CMS seeks public comment on the feasibility of extending COVID–19 vaccine reporting, education, and offering requirements to other congregate LTCFs. Specifically, CMS seeks public comment on:

- Potential barriers that other LTCFs may face in meeting new requirements, such as staffing, resident/client population characteristics, and potential unintended consequences;

- Any existing state or local licensing or certification requirements or facility policies related to vaccines for congregate community-based settings and any benefits or challenges from policy implementation;

- Who should be responsible for vaccine access for residents and staff who participate in multiple settings (such as both residential and day programs);

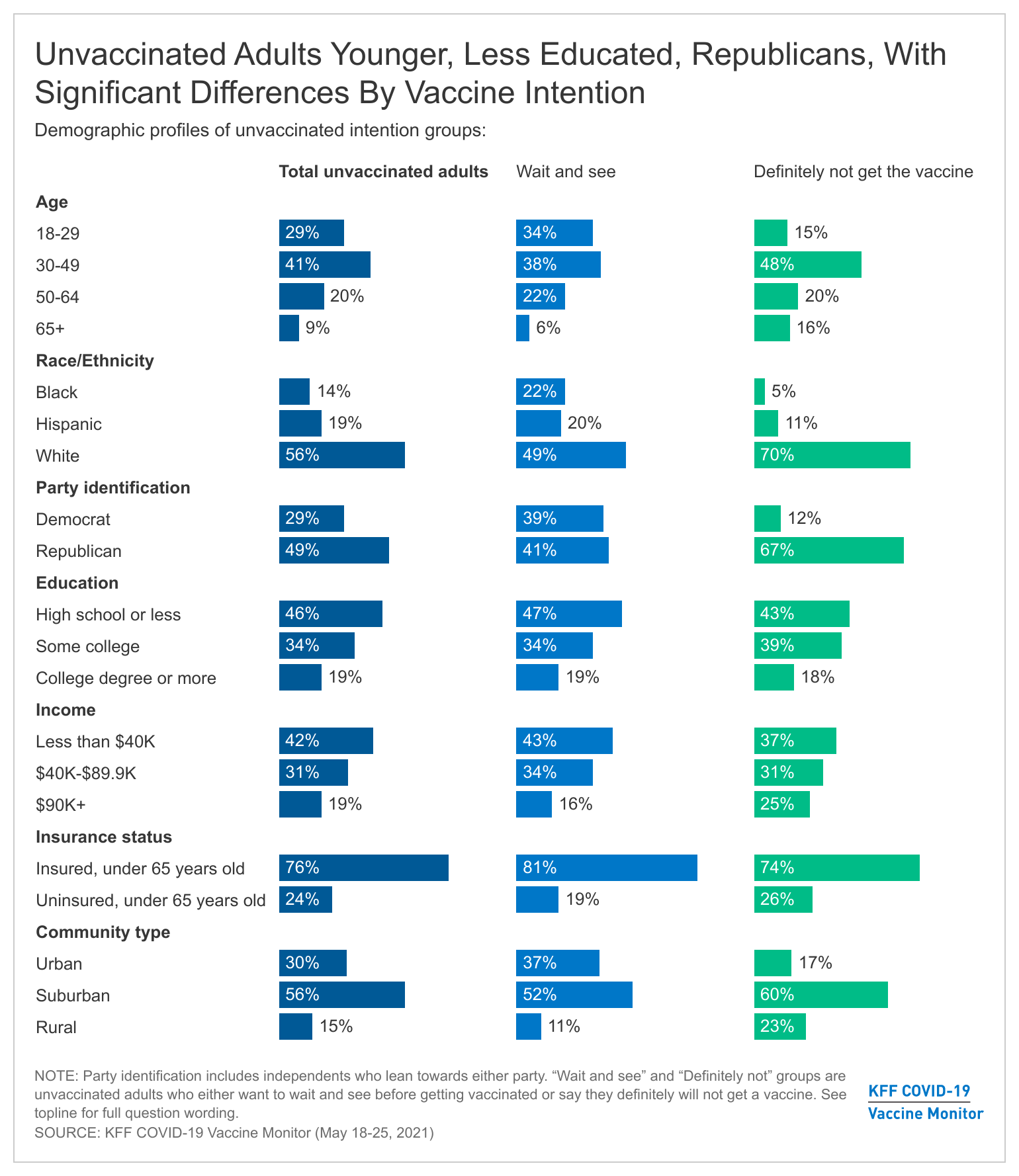

- How to ensure equitable vaccine access in congregate community-based settings and identify access barriers for staff;

- Available data on admission rates, average length of stay, comorbidities that may increase residents/clients’ risk of severe illness from COVID-19, and rates of employee turnover and employee sharing across congregate living settings.

Looking Forward

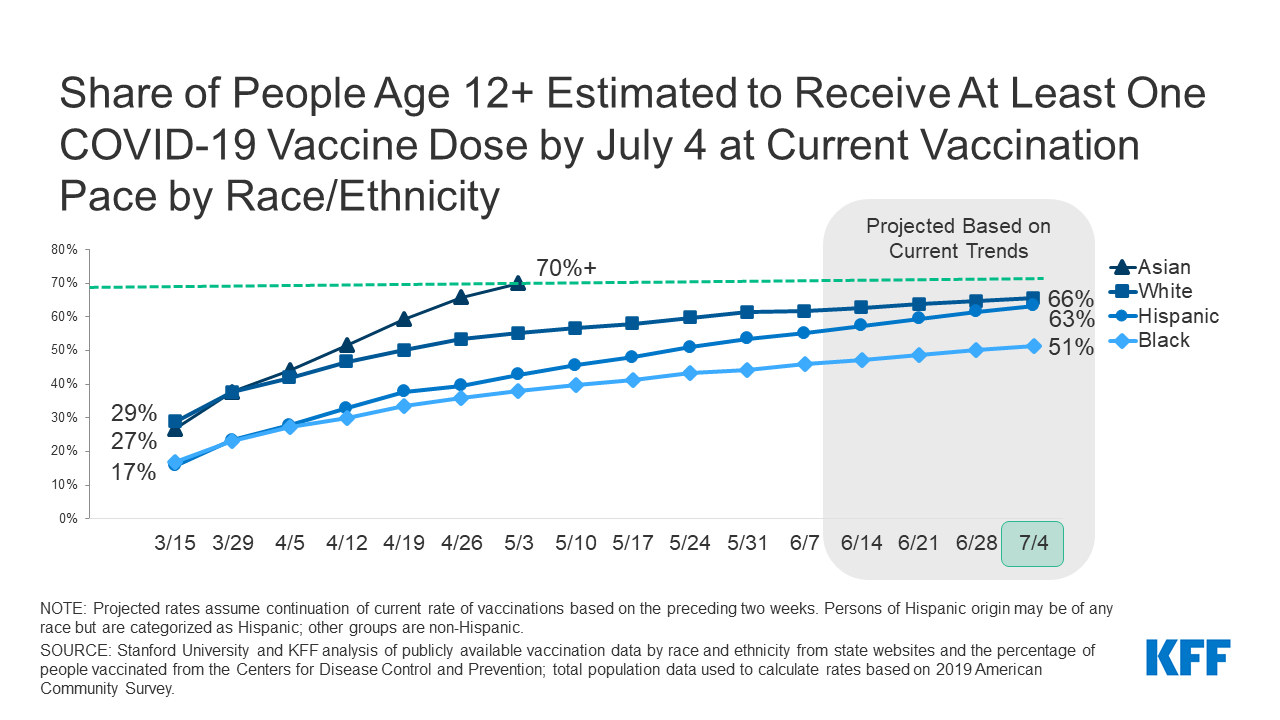

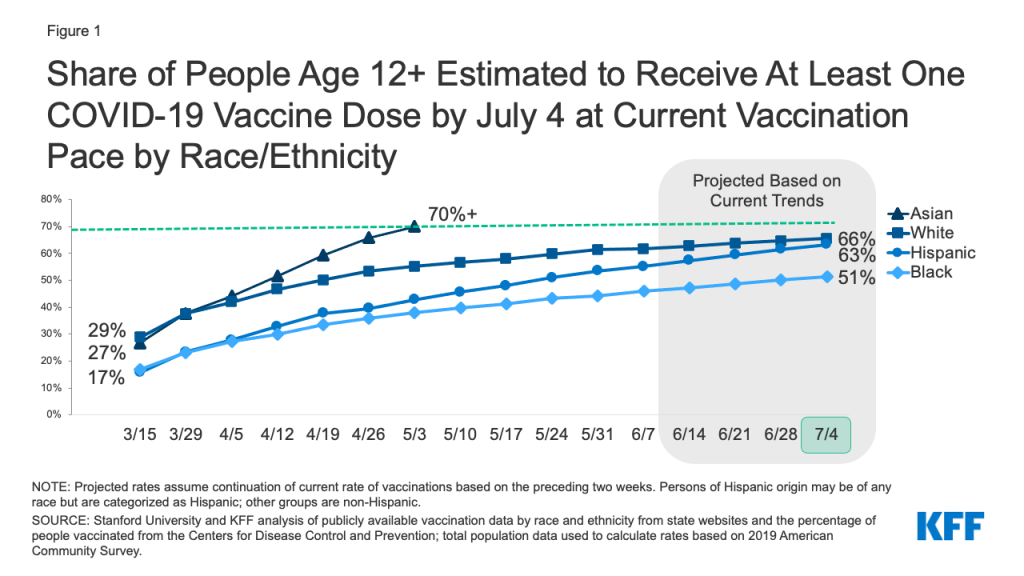

The new COVID-19 vaccine reporting, education, and offering requirements establish some standards and oversight for ongoing vaccination efforts in nursing homes, as the CDC Partnership has ended but the pandemic continues. Still, as CMS recognizes, data gaps remain, and the new standards currently do not apply across all LTCF types. The new rule does not require nursing homes to report COVID-19 vaccination or treatment data by resident/staff demographics such as race/ethnicity, continuing a data gap that pre-dates the pandemic. While ICF/IIDs are subject to the new education and offering requirements, there are not similar requirements for other long-term care settings that present similar COVID-19 risk factors for residents and staff, including inpatient behavioral health facilities and congregate community-based settings, and none of these settings are required to report data. Until data, resource, and oversight gaps across the long-term care continuum are filled, nonelderly people with disabilities may continue to experience disproportionate barriers to vaccine access compared to people in nursing homes, and the full impact of COVID-19 on this population will not be completely understood.

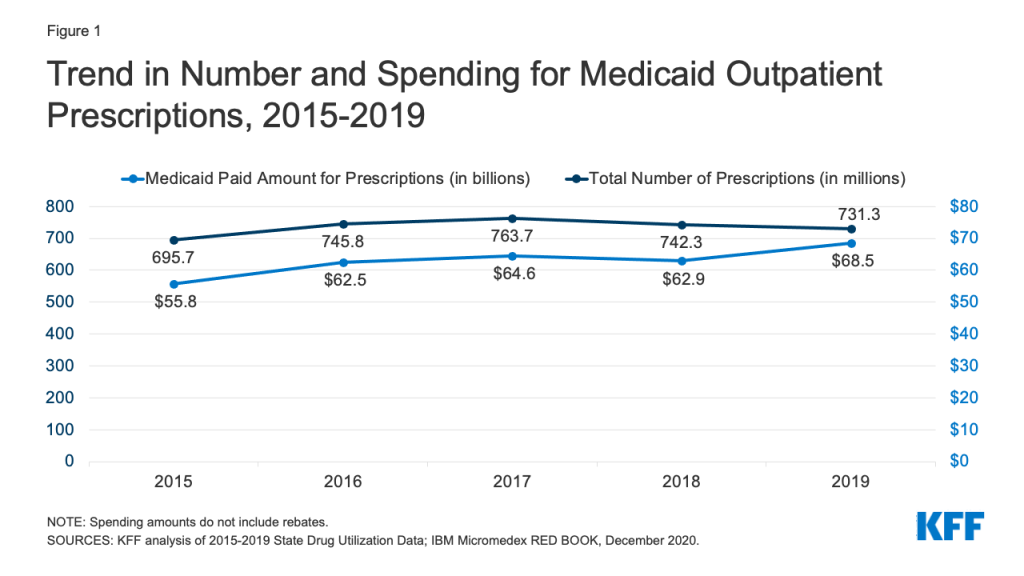

Because Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term care services and supports provided in congregate community-settings, states may consider leveraging the new enhanced federal Medicaid HCBS funding included in the American Rescue Plan to support vaccination efforts in settings across the long-term care continuum. Recent CMS guidance confirms that states may use these additional federal funds to facilitate COVID-19 vaccine access for Medicaid HCBS enrollees, many of whom reside into the categories of HCBS congregate care settings discussed above. For example, states can use the new funds to assist Medicaid HCBS enrollees with scheduling vaccination appointments, provide direct support services during appointments, provide transportation to appointments, develop in-home vaccination options, and conduct vaccine outreach and education. While the availability of effective vaccines has helped alleviate the toll the pandemic has taken on LTCFs, continued education and data on vaccine access can help inform ongoing COVID-19 response efforts.

Appendix

Facilities Mentioned in Interim Final Rule

Nursing homes: Licensed nursing facilities that are certified for participation in the Medicare and/or Medicaid programs are colloquially referred to as “nursing homes”. Nursing homes primarily provide 3 types of services: skilled nursing, rehabilitation, and long-term care. Payment for these services in facilities largely depends on licensure by either Medicare and/or Medicaid. In 2020, there were 15,327 nursing homes licensed to participate in Medicare and/or Medicaid serving about 1.3 million residents. Four percent of these facilities were certified as Medicare skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), two percent were certified as Medicaid nursing facilities (NFs), and the remaining 94% of facilities were certified to participate in both Medicare and Medicaid. Medicare typically pays for short-term skilled nursing care and rehabilitation while Medicaid covers short-term skilled care, rehabilitation, and long-term care in nursing homes.

ICF/IIDs: Intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities are residential facilities that provide active treatment services for people with these conditions. Active treatment refers to aggressive, consistent implementation of a 24-hour program of specialized and generic training, treatment, health services and related services. ICF/IIDs are an optional Medicaid benefit, though all states have adopted the benefit. The latest data indicate that there are 5,768 certified ICF/IIDs across all 50 states serving over 64,800 individuals. These facilities are 100% Medicaid funded, so all residents in these facilities must financially qualify for Medicaid.

Inpatient Behavioral Health Settings: Inpatient behavioral health settings include inpatient psychiatric hospitals (IPFs) and psychiatric residential treatment facilities (PRTFs). IPFs are facilities that provide short-term treatment (typically under 30 days) for individuals with mental illness. PRTFs are non-hospital facilities with a provider agreement with a state Medicaid agency. The age limit imposed by regulation for the PRTF benefit is 21 years of age.

HCBS Congregate Settings: HCBS is an umbrella term for long-term supports and services that are provided to people in their own homes or other community settings rather than institutions. These programs serve a diverse population, including many nonelderly adults with disabilities. The individuals in these settings often have multiple chronic conditions that can increase the risk from COVID–19. HCBS congregate settings include group homes, day habilitation sites, assisted living facilities, shared living/host home settings, adult foster care homes, and more.