What Do We Know About Health Care Access and Quality in Medicare Advantage Versus the Traditional Medicare Program?

Marsha Gold and Giselle Casillas

Published:

Executive Summary

While the majority of Medicare beneficiaries still receive their benefits through the traditional Medicare program, 30 percent now obtain them through private health plans participating in Medicare Advantage. As the number of Medicare Advantage enrollees continues to climb, there is growing interest in understanding how the care provided to Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans differs from the care received by beneficiaries in traditional Medicare.

Despite the interest, the last comprehensive review of research evidence on health care access and quality in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare is more than 10 years old and did not focus exclusively on Medicare (Miller and Luft 2002). That study found that health maintenance organizations (HMOs) provide care that is roughly comparable in quality to the care provided by non-HMOs (mainly traditional indemnity insurance), and that quality varied across health plans. It also found that HMOs used somewhat fewer hospital and other expensive resources in delivering care, with enrollees rating them worse on many measures of access and satisfaction. However, the market has changed substantially over the last decade, making it important that policymakers have available more current analysis, particularly on Medicare health plans.

This literature review synthesizes the findings of studies that focus specifically on Medicare and have been published between the year 2000 and early 2014. Forty-five studies met the criteria for selection, including 40 that made direct comparisons between Medicare health plans and traditional Medicare. An additional five studies are included, even though they have no traditional Medicare comparison group, because they include a comparison of health care access and quality in different types of Medicare Advantage plans. A full list of the studies included in this analysis is found in the Works Cited.

FINDINGS

What the Literature Shows

The review of the literature comparing quality and access provided under traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans suggests the following:

- HEDIS Effectiveness Metrics on Preventive Care. Medicare Advantage, on average, scores more highly than traditional Medicare on subsets of Medicare HEDIS indicators – primarily those pertaining to use of preventive care services. Two studies found Medicare preferred provider organizations (PPOs) outperformed traditional Medicare on some metrics (particularly mammography rates), though HMOs nevertheless performed better than PPOs. All of these studies were conducted prior to changes made by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to improve coverage of preventive services under traditional Medicare.

- Beneficiary Reports on Quality and Access (CAHPS). Medicare beneficiaries generally rated Medicare Advantage lower than traditional Medicare on questions about health care access and quality, especially if beneficiaries had a chronic illness or were sick; however, the difference in ratings between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage narrowed on some metrics by 2009 (e.g., overall care ratings). Keenan et al. (2009) found that sick beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage rated their plans substantially lower than beneficiaries of similar health status in traditional Medicare, and Elliott et al. (2011) found significantly lower CAHPS ratings (and greater disparities between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare) among vulnerable subgroups of beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage. Little is known about how CAHPS scores vary by type of Medicare Advantage plan since most studies are based on HMOs or periods in which HMOs were the main plan type.

- Potentially Avoidable Hospital Admissions. Based on six studies involving beneficiaries in a limited number of states and/or plans represented by the Alliance of Community Health Plans (ACHP), Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs are less likely to be hospitalized for a potentially avoidable admission than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Four of these studies rely on data prior to 2006, and reflect HMO experiences in mature markets.

- Readmission Rates. While a number of studies examine whether readmission rates differ among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, the evidence from these studies is inconclusive because findings differ across the studies and many studies lack adjustments for important potentially confounding factors.

- Health Outcomes. There is some evidence that good coverage, as defined by relatively low cost-sharing (whether through Medicare HMOs or through Medicare with supplemental coverage), may result in earlier diagnoses of some cancers compared to traditional Medicare alone. Treatment patterns for some cancers also may differ between Medicare HMOs and traditional Medicare, but studies do not show that this affects patient outcomes. However, the age of the studies, the gaps in controls for selection, and the evolving nature of guidelines for appropriate care limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

- Resource Utilization. Medicare HMOs appear to provide a less resource-intensive style of practice than traditional Medicare, as measured in studies examining end-of-life care, use of certain procedures, and overall utilization rate in HMOs, especially for hospital services. However, most of these studies provide little direct evidence of whether less intensive care is better or worse or how the appropriateness of care differs between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.

- Variation by Geography, by Plan Type, and by Plan Experience. On a variety of metrics, performance among Medicare Advantage plans varies substantially across plans, even among plans of the same plan type. The variations by market in more established HMOs with integrated delivery systems tend to be more represented in existing research, and to perform better. Performance on quality and access metrics varies across geographic areas, and the variations in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare ratings are not necessarily the same.

The Available Evidence has Substantial Limitations

To make a definitive comparison of both quality and access in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, one would ideally draw from studies with relatively recent data that is nationally representative in terms of both the characteristics of health plans participating in Medicare Advantage and the characteristics of beneficiaries covered by the Medicare program. Performance measures would capture a broad range of metrics assessing both quality of care and access to care, and would include enrollees’ assessments, process measures, and outcome measures. The comparisons would adjust for factors that might explain differences in performance between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, such as variations in medical practice by geographical location and patient health status. In an ideal world, studies would provide information to help clarify if differences vary by plan type, and how quality and access indicators compare for the typical Medicare beneficiary, as well as beneficiaries who are in relatively poor health with significant medical needs.

Unfortunately, while available evidence provides some insights, it falls short on many desirable dimensions. The most serious shortfalls are in the lack of timely data, the primary focus on HMOs rather than the full range of Medicare Advantage plans, and study populations that exclude important subgroups of beneficiaries (such as the under-65 disabled) and lack information on the experience of vulnerable subgroups of beneficiaries, such as those in poor health or with significant needs. In addition, available metrics are limited in their ability to capture performance across the full continuum of care and care for the total patient, particularly on a national basis.

Our review of the literature comparing quality and access measures between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage finds:

- Limited Insight into Experiences After Implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). With one limited exception involving hospice care, none of the 40 studies comparing Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare rely on data from 2010 or later. Thus, it is not yet possible to assess the performance of Medicare Advantage relative to traditional Medicare that reflects plan performance after the implementation of the Medicare Advantage payment changes included in the ACA (payment reductions, coupled with quality bonus payments). Fourteen of the 40 studies report only on experience in the 1990s or earlier, and of the 27 others covering the 2000-2009 period, 16 provide estimates between 2006 and 2009, after the introduction of the Medicare prescription drug benefit.

- Studies Reflect Mainly HMO Experience, Not Newer Plan Types. Almost all of the literature applies to the experience of beneficiaries in HMOs, rather than in the full range of plans that are currently available. In 2014, for example, one-third of all Medicare Advantage enrollees are in plans other than HMOs, mainly PPOs. Only three of the 40 studies that compared traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage (and two of the five that compared Medicare Advantage plans only) included findings that were specific to Medicare PPOs. Others either are limited to HMOs, apply to a period when HMOs were the overwhelming plan type, or do not analyze data by plan type. As a result, the results are not generalizable to the Medicare Advantage program as a whole as contrasted with the experience of its older HMO component.

- Limited Insight into the Experience of Beneficiaries with More Complex Medical Needs. Few of the existing studies provide insight on how Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare perform on quality and access metrics for beneficiaries whose health characteristics suggest that they could have more complex needs. Only four studies, all based on beneficiary survey data, focused explicitly on subgroups of the Medicare population defined by the authors as high-need based on health or functional status (Keenan et al. 2009, Elliott et al. 2011, Pourat et al. 2001, and Beatty and Dhont 2001). One study (Elliott et al. 2011) also examined disparities in care for vulnerable subgroups defined by various socioeconomic indicators, along with health status. The inability to reflect the experiences of beneficiaries with significant health needs is a major limitation in the literature.

- Data Constraints Limit National Studies. While several studies are national in scope (plans and beneficiaries), the metrics they include are limited by available data. Of the 17 national studies comparing Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare (of 40 in total), 10 rely exclusively on CAHPS or other national population surveys, and seven use HEDIS data compared to claims data for traditional Medicare. Vital statistics data dealing with mortality were used in two of the studies as well. Studies on many metrics relevant to quality either do not exist (like intermediate outcomes for beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions or the personal experience with care of these patients) or, like studies of potentially avoidable admissions and readmissions, depend on data from a limited set of states or locales.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Despite great interest in comparisons between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, studies comparing overall quality and access to care between Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare tend to be based on relatively old data, and a limited set of measures.

On the one hand, the evidence indicates that Medicare HMOs tend to perform better than traditional Medicare in providing preventive services and using resources more conservatively, at least through 2009. These are metrics where HMOs have historically been strong. On the other hand, beneficiaries continue to rate traditional Medicare more favorably than Medicare Advantage plans in terms of quality and access, such as overall care and plan rating, though one study suggests that the difference may be narrowing between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage for the average beneficiary. Among beneficiaries who are sick, the differential between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage is particularly large (relative to those who are healthy), favoring traditional Medicare. Very few studies include evidence based on all types of Medicare Advantage plans, including analysis of performance for newer models, such as local and regional PPOs whose enrollment is growing.

As the beneficiary population ages, better evidence is needed on how Medicare Advantage plans perform relative to traditional Medicare for patients with significant medical needs that make them particularly vulnerable to poorer care. The ability to assess quality and access for such subgroups is limited because many data sources do not allow subgroups to be identified or have too small a sample size to support estimates. Also, in many cases, metrics employed may not be specific to the particular needs or the way a patient’s overall health and functional status or other comorbid conditions influence the care they receive.

At a time when enrollment in Medicare Advantage is growing, it is disappointing that better information is not available to inform policymaking. Our findings highlight the gaps in available evidence and reinforce the potential value of strengthening available data and other support for tracking and monitoring performance across Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare as each sector evolves.

Report

Introduction

Medicare is critical to the well-being of the nation’s seniors and people with disabilities, many of whom have low to moderate incomes, complex health care needs, and other characteristics that leave them disproportionately vulnerable.1 While the majority of Medicare beneficiaries still receive their benefits through the traditional Medicare program, 30 percent now obtain their benefits through private health plans participating in Medicare Advantage.2 As the number of enrollees in Medicare Advantage continues to climb, there is growing interest in understanding how care provided to Medicare beneficiaries in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage differs.Despite the considerable interest in this topic, solid analysis summarizing existing research comparing Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare on various quality and access metrics is relatively limited. Historical reviews of performance differences across health plans have generally focused on comparisons of organizational structures (like health maintenance organizations or HMOs) rather than focusing on particular payers, like Medicare. The most widely cited reviews available have been conducted over the years by Miller and Luft, with the most recent review covering work through mid-2001.3 It concluded that the quality of care provided by HMOs was roughly comparable to traditional insurance, though it varied across health plans; HMOs used somewhat fewer hospital and other expensive resources to deliver care compared to traditional insurance, and had lower ratings by enrollees on many measures of access and satisfaction. An earlier study in the series (Miller and Luft 1997) noted that Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions had worse outcomes in HMOs.4

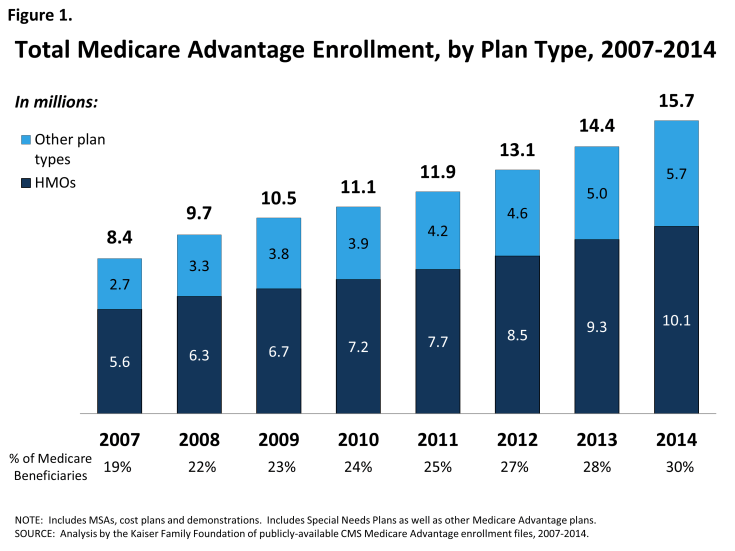

Since these reviews were published, the environment has changed considerably. The historical base of HMOs in nonprofit staff and group model plans has shifted considerably, with new growth in for-profit plans that use more decentralized provider networks that tend to be less integrated.5 Further, since the mid-2000s, the number and share of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in private plans, now called Medicare Advantage, has increased dramatically, and while most enrollees are in HMOs, a growing number are enrolled in other types of plans, such as local and regional PPOs (Figure 1).

The policy environment and incentives facing providers in the Medicare program also have changed in ways that put increasing emphasis on payments that take into account performance on quality and efficiency metrics. For Medicare Advantage, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 (federal health reform law) enacted changes in payments to plans that are now being phased in, slowing the increase in Medicare Advantage payments and linking them more closely with performance on quality and other performance metrics.6 Medicare Advantage plans that score four or more out of five stars are provided bonus payments and those that score the highest (so-called “five star plans”) gain other advantages, particularly the ability to continuously enroll beneficiaries throughout the year.7 Payment to hospitals, physicians, and other providers in the traditional Medicare program also are increasingly tied to quality metrics as a result of changes in the ACA and other legislation. The ACA also improved coverage of preventive services under traditional Medicare, which has been a metric in which managed care plans have historically performed better.

Such changes increase the interest within the policy community in current information comparing the quality of care provided to beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare. Proponents of the insurance industry argue that quality under Medicare Advantage has improved and is better than under the traditional program – an accomplishment, they argue, that could be undermined by ongoing reductions in payments as required under the federal health reform law.8

In a recent review, Newhouse and McGuire (2013) summarized three studies they coauthored that compared Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare, and concluded that the findings from those studies favored Medicare Advantage.9 The review has gotten considerable attention.10 Lost in the discussion, however, is the fact that the main thrust of the article focused on efficiency and selection within Medicare Advantage, with the authors acknowledging that research comparing the quality of care in Medicare Advantage versus traditional Medicare is limited.

Methods

This study seeks to fill the gap in available information on current evidence comparing quality and access in Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare. Unlike earlier literature reviews, the focus of this paper is on Medicare, and limited to studies that are relatively current; that is, published between 2000 and early 2014.

Study Sources and Inclusion Criteria

We identified the initial list of studies using a Google Scholar search for articles on “Medicare Advantage/Medicare HMOs” published since 2000. We reviewed titles and abstracts to identify studies focusing on access/quality metrics and including a design that had some comparison group—typically traditional Medicare, or what some still refer to as Medicare fee-for-service (FFS). Because Google Scholar does not index the most recent year’s publications and is a less established search source, we also contracted with a trained health research librarian to conduct a formal Medline search covering the period 2000−2014.1 That search used the terms “Medicare health plans,” “Medicare HMO,” “Medicare Advantage,” and “Medicare Advantage PPO” in comparison to “FFS Medicare,” “Medicare,” and “traditional Medicare,” with the keywords “quality of care,” “access,” and “outcomes”.2 To ensure coverage of studies that may be relevant to the policy debate but are not found in the academic literature, we also reviewed the sources cited in industry briefs and the most recent Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) report to Congress on Medicare Advantage.3 In addition, we checked citations in those studies identified for any other relevant studies not already identified.4

To be included in the review, studies had to include (1) a written description of methods and data sources, (2) a formal comparison group, and (3) outcome measures relevant to access or quality. Although we did not otherwise exclude studies based on the quality of their methods, we reviewed articles for how they handled such potentially confounding factors as geographic location, enrollee mix, and health and risk factors associated with selection. Because our analysis focused on Medicare health plans available for general enrollment, we excluded studies focused on specialized plans—particularly social HMOs, PACE, and Special Needs Plans (SNPs).

Relevant Metrics of Interest

Health care quality problems can arise though underuse, overuse, and misuse of services.5 Some of these domains are better captured in existing quality metrics than others.6 Because the review was focused on access and quality of health care received by beneficiaries in different types of insurance arrangements, rather than insurance per se, studies focused primarily on benefits or the factors that influence health plan selection were not considered. Five categories of metrics are considered in this paper.

HEDIS Effectiveness of Care Metrics.

HEDIS measures, which Medicare health plans report to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), are central to oversight in Medicare Advantage. In 2014, Medicare Advantage plans were required to submit audited data consistent with National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) specifications for 25 metrics on health care effectiveness and another three on access and availability of services, among other metrics.7 HEDIS effectiveness indicators focus on the processes of care or intermediate outcomes rather than ultimate outcomes; metrics relevant to those with chronic illness are limited, though efforts are underway to broaden the measure set. Patient-level data used to support these metrics come from claims, encounter data, and for some metrics, medical records. A subset of these metrics is used to support calculation of Medicare Advantage plan star quality ratings, the basis for bonus payments to plans. Increasing efforts have been made to align reporting requirements across Medicare Advantage plans of different types, but data historically have been most available for HMOs and least available for private FFS plans and regional PPOs.8 HEDIS metrics are not routinely calculated for traditional Medicare. MedPAC is considering better ways to align requirements and metrics across programs, taking into account the differences in data sources used in each sector.9

CAHPS™ Quality Metrics.

CAHPS is a health plan member survey that provides patient reports of care experiences with their plan, including ratings of access to care and satisfaction with the plan and its providers.10 To support its use, CMS conducted a related survey of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare residing in those same geographical areas (in 2011, it replaced this survey with a requirement that freestanding prescription drug plans collect CAHPS data). Using its contractors, CMS has developed a number of composite measures of reported care and use of preventive services, as well as global health ratings. Some of the same items are included in standard national surveys, such as the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) and the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). Because they provide insight into how beneficiaries view care, beneficiary surveys long have been a central component of most efforts to examine access and quality of care in Medicare.

Quality Metrics around Hospitalizations.

From a quality and value perspective, metrics that provide information on the appropriateness and quality of hospital care are of growing interest. Key metrics in this area focus on the appropriateness of hospital admissions that potentially could be avoided by more timely and appropriate primary care, the appropriateness and quality of facilities and professional services used, and the ability to structure discharges in ways that avoid personally and financially costly complications and hospital readmissions. CMS now captures data on case-mix adjusted Medicare rehospitalization rates as part of HEDIS reporting from health plans. In the absence of national data, most research on this topic has used data available through all-payer discharge data sets available in selected states and from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ’s) databases. Only some of these files have appropriate identifiers to distinguish enrollment in Medicare health plans, and the timeliness of information often lags. While adjusting for case mix and severity is important in all comparisons of quality, it is particularly important in studies of hospital appropriateness or outcomes, when poor outcomes may be small in number and highly sensitive to the mix of enrollees.

Other Utilization Metrics.

Given the limitations in available data that directly measure access and quality of health services for beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, researchers have included various other measures of utilization as a proxy for direct measures of these aspects of care. Like the hospital utilization measures, some of these metrics target specific kinds of utilization that have been used as markers for overuse, underuse, or misuse of services, including emergency department (ED) visits, patterns of care at the end of life, procedure use for urgent versus non-urgent conditions, or high-cost procedures versus others. Medicare Advantage plans report on some of these metrics in the Utilization and Relative Resource Use section of the HEDIS performance monitoring submission form. Utilization-based measures can be difficult to interpret as quality metrics when norms defining appropriateness are lacking or in dispute, and when it is unclear what constitutes overuse or underuse and whether overuse or underuse are markers for better or worse care. Such measures also require careful risk adjustment for selection. Studies that use aggregate measures of utilization probably are better interpreted as indications of resource use rather than quality of care.

Health Care Outcomes and Mortality.

Ultimately, the goal of medical care is to improve patient outcomes and quality of life. Data sets available for studies of this type are limited and those that exist do not always include good information on health insurance type or adequate data to link with other sources containing such data. There are also methodological challenges in adjusting for patient selection and mix adequately. Cancer studies are supported by cancer registry data maintained by states and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance and Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) data, among others.

Findings

Overview of Published Studies

A total of 45 unique studies were identified using the methods and criteria discussed (Table 1), of which 40 involved comparisons between Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare. The other five studies made comparisons among Medicare HMOs or between HMOs and PPOs, but did not compare Medicare Advantage plans to traditional Medicare. A complete list of all the studies that are included in our review is found at the end of this document. An additional six studies compared the care received in Medicare health plans to care in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) system; since they involve a highly specialized comparison, they are not included in the core analysis and text but their findings are summarized in the Appendix.

| Table 1. Overview of Reviewed Studies | |

| (All studies involved a comparison to traditional Medicare unless noted) | |

| Type of Quality/Access Metric | Number |

| HEDIS Effectiveness of Care Indicators (studies focused mainly on prevention metrics) | |

| • Medicare Advantage vs. traditional Medicare program | 3 |

| • Variation across health plan types only (no TM comparison) | 4 |

| Beneficiary Reports on Quality and Satisfaction | |

| • CAHPS-based comparisons | 6 |

| • MCBS, NHIS, and other surveys | 4 |

| Appropriateness of Hospital Use and Outcomes | |

| • Avoidable Hospitalizations | 6 |

| • Quality of Admitting Hospital/Physician/Care | 5 |

| • Readmission Rates | 3 |

| Other Utilization Measures (reported in the HEDIS dataset or elsewhere) | |

| • Service Use at End-of-Life | 2 |

| • Procedure Use (1 study has no TM comparison, looks only at HMOs) | 2 |

| • Overall Utilization | 3 |

| Health Care Outcome and Mortality | |

| • Overall Mortality | 1 |

| • Stage of Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes | 5 |

| • Functional Status | 1 |

| NOTE: The table classifies studies based on their primary area of focus. One study (Ayanian et al. 2013) included selected CAHPS indicators along with the main analysis of HEDIS effectiveness indicators. To avoid double counting, it is not listed twice here. | |

| SOURCE: Authors’ analysis based on review of published papers. | |

Characteristics and Relevance of Core Studies

Table 2 summarizes the 40 studies that make comparisons between Medicare Advantage (or predecessor program health plans) and traditional Medicare. Studies (the rows) are grouped by type of quality or access metric,1 with columns providing detail on the main focus and characteristics of individual studies and the types of study controls and comparisons made. Table 3 provides the same information for the five studies involving comparisons solely within Medicare Advantage. Ideally, one would want studies with current data, across a wide variety of health plans nationally, using diverse outcome measures, with good controls for other factors that could explain differences in performance between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Unfortunately, the studies identified fall short in many of these areas.

Timeliness.

While this review aims to assess current Medicare Advantage practice, the studies available to support such an assessment are very limited. With one limited exception – an analysis of hospice use – none of the studies comparing Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare include data from 2010 or later, which means none cover the experience of beneficiaries after the changes enacted in the ACA. Fourteen of the 40 studies use data from the 1990s or earlier. Of the 27 other studies covering the 2000-2009 period, 16 provide estimates for 2006 or later after the Medicare Advantage changes introduced in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 began to drive the market with the introduction of the Medicare prescription drug benefit in 2006.2

Scope of Health Plans Studied.

While Medicare health plans have become increasingly diverse, and more beneficiaries are enrolling in Medicare PPOs, the research to date comparing the traditional Medicare program to Medicare Advantage plans still mainly reflects the HMO experience. Only three of the 40 studies that compared traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage (and two of the five that compared Medicare Advantage plans only) included findings that were specific to Medicare PPOs. Most studies use data for a time period in which HMOs were the main Medicare health plan option. Some of the more recent studies are limited to HMOs to address data constraints or create more homogeneous comparisons. Other studies are not limited to HMOs but do not provide evidence that distinguishes findings by plan type or other plan characteristics. For example, among studies that involved comparisons to traditional Medicare, only two studies analyzed Medicare Advantage plan performance by plan maturity (years of Medicare Advantage experience) and three (two without a traditional Medicare comparison) analyzed the relationship between performance and plan tax status (for profit/nonprofit).

Results Targeting Beneficiaries with More Complex Medical Needs.

Few of the existing studies provide insight into how Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare perform on quality and access metrics for beneficiaries whose health characteristics suggest that they could have more complex or specialized needs. Only four studies, all based on beneficiary survey data, focused explicitly on subgroups of the Medicare population defined by the authors as high need based on health, functional status, age, and/or income (Elliott et al. 2011, Keenan et al. 2009, Pourat et al. 2006, and Beatty and Dhont 2001). In the first two, using CAHPS data for 2003-2004 and 2009 respectively, Keenan et al. 2009 compared findings for beneficiaries based on self-reported health status, and Elliot et al. 2011 examined disparities for seven vulnerable subgroups (by socio-economic status and perceived health status). Using older data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (1996 and 1994 respectively), Pourat (2006) looked at chronically ill Medicare beneficiaries and Beatty and Dhont (2001) looked at under-65 disabled beneficiaries and elderly beneficiaries with one or more disabilities.

Several other studies included health status and health indicators as covariates in their analysis, but did not focus on these subgroups for comparisons of quality and access between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Almost all studies were either limited to beneficiaries 65 and older (versus younger beneficiaries qualifying by virtue of disability) or did not analyze the experience of under-65 disabled in Medicare Advantage versus traditional Medicare. While some of this reflects the exclusion in this review of studies on specialized health plans, such as Special Needs Plans, research shows that meaningful numbers of beneficiaries who are disabled and under-65 have long been enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans open for general enrollment.3 The inability to target findings to subgroups with more extensive needs is a major limitation since the studies that exist tend to show that such individuals, at least in survey data, are more likely to report more negatively on their care, regardless of the system they are in, and some studies show this more in Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare (see Table 5).

Studies of National Scope are Limited.

Available studies include some that are national in scope, comparing Medicare health plans to traditional Medicare; 17 of the 40 studies that have traditional Medicare comparisons fall in this category. Such studies are feasible because CMS has supported the development of data that better support such analysis. In particular, CAHPS data support such comparisons and HEDIS data collection associated with Medicare Advantage provide nationally-representative data that on some metrics can be compared to estimates from claims generated in traditional Medicare. However, the data available to support comparisons on other types of metrics are limited nationally, which means that many analyses are feasible only for subgroups of states or communities that participate in various data collection efforts. For example, diagnostic specific studies involving hospitalizations are only feasible in some states with all payer hospitalization data sets since encounter data that equal claims data have not been collected historically for Medicare Advantage. Further, studies that link care for particular patients across settings or conditions tend not to be feasible in the absence of clinical data that allow for stronger comparisons between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. In general, the lack of clinical data that link patient care across different settings has created a major barrier to developing more robust and meaningful quality measures, as many have noted. For example, the National Quality Forum has identified care coordination, patient centered care and outcomes, and care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia as three of the top five priorities in terms of future development of measures that matter.4

Control for Selection and Confounding Variation.

Because Medicare Advantage enrollment is voluntary, it is important to control for characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries that may influence their choice of health plan and also the outcomes of their medical care. Roughly speaking, such variables include socio-demographic characteristics (for example, age, sex, race, and ethnicity) and specific health metrics that relate both to overall health status and the severity of comorbidities associated with particular conditions under study. Because practice patterns and socio-demographic characteristics of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage may vary geographically, MedPAC also has recommended that comparisons between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare be based on beneficiaries in the same geographical payment areas.5 Such adjustments reflect both the considerable variation in Medicare Advantage enrollment rates across the country and also the differences in individual markets that are likely to influence care both in Medicare Advantage and in traditional Medicare. In Table 2, the 40 studies that compare traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage are described in terms of their use of locality, socio-demographic, and health status/risk controls, though more detail in the actual techniques used in individual studies are covered in later tables. The aggregate analysis suggests that most studies make some effort to control for confounding sources of variation, such as geography, population and health status, but do so to varying degrees. In many cases, the data available to support such adjustments are limited.

Study Findings by Type of Metric

This section reviews findings from studies organized by each of the five types of quality or access metrics: HEDIS effectiveness of care metrics, beneficiary-reported access and quality metrics, appropriateness and outcomes of Medicare hospitalizations, other utilization and resource use metrics, and health outcomes and mortality. In each subsection, a table summarizes all the studies of that type.

HEDIS Quality Metrics for Effective Care.

Studies Comparing Medicare Advantage to Traditional Medicare. Three studies (by two groups of researchers) provide direct comparisons between Medicare Advantage (mainly HMOs) and traditional Medicare on subsets of HEDIS indicators for effective care (Table 4). The Ayanian studies (2013a and 2013b) used relatively recent data (2003 through 2009) and adjusted for geographical location and socio-demographic characteristics of Medicare Advantage enrollees. The Brennan and Shephard (2010) study used data for 2006-2007 and adjusted for geography only. All three, however, find that Medicare HMOs outperform traditional Medicare on the subset of HEDIS indicators examined. Ayanian et al. (2013a) used indicators that could be constructed from claims data, comparing Medicare HMOs to traditional Medicare, with beneficiaries matched by location and selected demographics. The results showed higher scores for HMOs than for traditional Medicare in all years, with the difference greatest for 21 large, nonprofit HMOs established before 2006. The HEDIS metrics included were heavily weighted to preventive care, which previous studies had shown to be a strength of HMOs.6

With respect to mammography, Ayanian et al. (2013b) also found more favorable patterns in Medicare HMOs compared to traditional Medicare, but the difference was less marked for Medicare PPOs relative to traditional Medicare. Brennan and Shephard’s (2010) analysis also included findings for PPOs for 8 of the 11 prevention measures analyzed. The authors’ findings, which largely reflect the HMO experience, showed substantially better performance by Medicare Advantage plans relative to traditional Medicare on eight measures, slightly better performance on one measure, and worse performance on two measures (monitoring of persistent medications and persistence of beta blockers), with Medicare Advantage performance particularly high on well-established metrics that Medicare Advantage plans had been required to report for many years (versus newer metrics). However, the findings from the comparison were limited because over this time period (2006-2007) PPO metrics used only administrative data whereas HMOs also could take advantage of medical records data.

Because Medicare health plans (at least HMOs) have been required to report on HEDIS metrics since 1997, their better performance on these indicators could be expected. However, there is not strong evidence linking public reporting per se to subsequent improvements in quality of care.7 With many HEDIS metrics now tied to Medicare Advantage bonus payments, health plans should have strong financial incentives to improve HEDIS scores. However, performance on HEDIS’s preventive indicators within traditional Medicare also could improve because of changes in Medicare benefits that remove cost sharing for many preventive services.

Variation across Types of Medicare Advantage Plans. Because comparisons involving traditional Medicare provided limited insight into newer types of Medicare Advantage plans, we expanded the review to include four studies that use HEDIS effectiveness scores to compare performance across different Medicare Advantage plan types (see Table 4). The most recent study (MedPAC 2014a) compared HMOs and local PPOs reporting for both 2011 and 2012 on a variety of HEDIS metrics, although with no adjustments for location, socio-demographic characteristics, or risk. The authors found differences in HEDIS scores by plan type narrowing over time as scores for Medicare Advantage plans improved, but HMOs still outscored local PPOs on most measures (PPOs only scored better on 4 of 42 measures), particularly on metrics that require extraction of medical records data. NCQA (2013) found improvements on some indicators, particularly those included in the star ratings used for bonus payments. There was a decline, however, in scores for substance abuse treatment metrics, particularly for Medicare PPOs.

Trivedi et al. (2005) found evidence that HEDIS quality improvements in HMOs were associated with reduced disparities in care for whites and blacks, though extensive differences across race remained. Studying HMOs in 1998, Schneider et al. (2005) found not-for-profit plans outperformed for-profit plans, but could not disentangle tax status from managerial processes in certain types of plans (e.g., network/independent practice association (IPA) versus group/staff). MedPAC (2014a) also has documented wide variation across Medicare Advantage plans, with newer plans performing worse than more established ones, even of the same type (i.e., HMOs).8 Ayanian et al. (2013a) also found stronger performance by more mature and larger nonprofit plans.

Together, these studies suggest that the better performance of Medicare HMOs relative to traditional Medicare on HEDIS metrics will vary with HMO characteristics and may not be generalizable, at least to the same extent, to other types of Medicare Advantage plans.

CAHPS and Similar Beneficiary-Reported Metrics

This review identified 10 studies comparing Medicare health plans to traditional Medicare using beneficiary survey data (Table 5), in addition to another study that primarily focused on HEDIS effectiveness but also include a few CAHPS metrics (see Ayanian et al. 2013a in Table 4). The most recent studies use CAHPS data, many of which appear to be undertaken by members of the CAHPS research team, with which CMS had contracted to work on Medicare CAHPS.

While designs varied across the CAHPS studies, the studies as a whole provide complementary insights and used similar measurement techniques and adjustments for case mix and geography. The earliest study (Landon et al. 2004), reporting on the 2000 and 2001 time frame, generally found that traditional Medicare was rated higher than Medicare health plans, which at that time were predominantly HMOs. Traditional Medicare was rated higher on global measures, personal physician ratings, and in absence of problems in getting needed care. Medicare Advantage plans were better at prevention and paperwork, but performance on all metrics varied considerably across states and regions, which the authors attribute to differences in norms of care rather than characteristics specific to plans.

More recent studies suggest that traditional Medicare continues to perform better on most beneficiary-reported metrics, particularly by beneficiaries who are in relatively poor health (Keenan et al. 2009). Another recent study by Elliot et al. (2011) also found larger differences in ratings between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage for beneficiaries with certain vulnerabilities, including those with low incomes, no high school degree, poor or fair self-rated health, those older than 85 years, women, and Blacks (Elliott et al. 2011). Ayanian et al. (2013a) found the difference in ratings between Medicare HMOs and traditional Medicare for personal care physicians and specialists to be narrowing by 2009 but also showed that beneficiaries still rated larger, non-profit, and older HMOs more highly than newer HMOs (see Table 3). Keenan et al. (2010) also reports more variability among Medicare Advantage plans compared to traditional Medicare.

For the most part, earlier studies using other beneficiary surveys have reported findings consistent with those from CAHPS. Two of the four studies using surveys other than CAHPS showed that beneficiaries rated care better in traditional Medicare than in Medicare HMOs (Safran et al. 2002; Pourat et al. 2006), one showed beneficiaries rated care as the same (Balsa et al. 2007) and the fourth had mixed findings (Beatty and Dhont 2001).

The Pourat et al. 2006 and Beatty and Dhont 2011 studies also are notable for including less healthy subgroups (chronically ill, those with functional disability). Pourat et al. 2006 (using 1996 data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey) found that higher scores for traditional Medicare than Medicare Advantage held up when the analysis was conducted by chronic condition, disability, and health status, that the difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare was greater among those with chronic conditions than those without, and that traditional Medicare scores also were higher for beneficiaries with supplemental coverage than those without. Beatty and Dhont 2001 found that among their sample, Medicare Advantage scored better than traditional Medicare on access and affordability but not satisfaction, while those who were least healthy or most disabled rated systems more negatively regardless of plan type.

While Ayanian et al. (2013a) shows that differences may be narrowing over time on some metrics, these studies as a whole show that beneficiaries tend to rate Medicare Advantage plans lower than traditional Medicare on items related to health care access and quality, and this is especially true for beneficiaries in relatively poor health. While the direction of findings from studies involving CAHPS metrics are in the opposite direction from those using HEDIS effectiveness studies, both sets of studies show considerable variation in ratings across plans and geographic locales.

Appropriateness and Outcomes of Medicare Hospitalizations

For purposes of this analysis, we have grouped the next set of studies by their outcome variables: potentially avoidable hospitalizations, quality of admitting hospital/physician, and readmission rates (Table 6).

Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations. Six studies were identified in this area, four of which use data from subsets of states participating in AHRQ’s Hospital Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Of the other two, one uses a single state’s all payer discharge data, and the other uses data from a subset of HMOs that it then matches to traditional Medicare data. With the exception of one largely descriptive study with few controls for confounding factors (Friedman et al. 2009), each of the studies finds that potentially avoidable admissions are lower for Medicare Advantage enrollees than for traditional Medicare, though four studies rely on data before 2006, and reflect HMO experience in mature markets.

Two of six studies are less transparent than the others on methodological issues, and appear to use fewer statistical controls, though they use more recent data (Friedman et al. 2009, Anderson 2009). Friedman et al. (2009) had a broader scope than other studies (13 states) and used AHRQ Prevention Quality indicators.

The findings showed no difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare on potentially avoidable hospitalizations; however, the analysis was mainly descriptive and did not include controls for patient selection or risk. Anderson’s study (2009), funded by America’s Community Health Plans, an industry association for nonprofit health plans, is not well documented and its methods appear to include no adjustments aside from selecting traditional Medicare data for beneficiaries in the same counties as the Medicare Advantage plans. The HMO comparison in the Anderson study was limited to a subset of HMOs known for their more integrated health care systems, and found that such systems have considerably lower rates of hospitalizations for potential avoidable admissions.

The other four studies span a small number of states and are older but included more statistical controls. Nicholas’s (2013) study linked discharge data to Medicare enrollment files in four states to estimate rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Over the period studied (1999-2005), Medicare enrollees in health plans largely were in HMOs. After adjusting for differences in selection, the study found that ambulatory care sensitive admission rates were lower in Medicare Advantage plans than in traditional Medicare. It further found that the reductions were driven primarily by admissions where inexpensive, short term intervention and routine provision of maintenance medications can reduce risk of hospitalization. The conclusions noted that this is a positive sign that the difference could reflect care management in HMOs, which would make the findings more robust. Using 2004 data from four states, Basu (2012) compared potentially avoidable hospital admissions to “marker” admission rates (that is, admissions for conditions expected to be less discretionary) in Medicare Advantage (largely HMOs) in three states, finding that HMOs performed better than traditional Medicare in all three states and across four racial groups. The difference was particularly strong in the two states with the most mature managed care markets. An earlier study by Basu and Mobley (2007, using 2001 data), covering four states, also showed lower rates of preventable hospital admissions in three of the four states and an indication that effects were particularly strong in the two states with the most mature managed care. The final study (Zeng et al. 2006) is older and included only one state (California), and its findings are consistent with the others.

Though these stronger studies are not necessarily as current and nationally-representative as they might ideally be, they collectively point to lower rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in HMOs compared to traditional Medicare, at least in states with mature HMO markets.

Quality of Admitting Hospital and Specialist Care. Five studies compared the hospitals or specialists used by hospitalized patients in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. As a whole, the findings of this body of work are inconclusive and four of the five studies are based on findings from single states.

Using HCUP data from 13 states, Friedman and Jiang (2010) compared risk-adjusted mortality rates and patient safety indicators for hospitals used by Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries in urban areas with two or more hospitals. Findings were mixed. HMO patients were admitted to hospitals with higher-mortality rates but also to hospitals with lower rates of events threatening patient safety. Researchers also found greater variability across HMOs than in traditional Medicare in the use of high and low mortality hospitals for surgical care. Huesch (2010) found that Florida HMO patients were less likely to see cardiologists with a favorable outcome profile (lower morality profile), though physician characteristics such as specialty, year, and country of training were otherwise similar across settings. Basu and Friedman (2013) found hospitalized elderly Medicare beneficiaries in Florida HMOs in 2002 at higher risk for selected adverse outcomes associated with iatrogenic pneumothorax, post-operative respiratory failure, and accidental puncture or laceration than hospitalized elderly beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. The final two studies (Luft 2003 and Erickson et al. 2000; see Table 6) each based on a single state in the mid-1990s, had conflicting results.

Readmission rates. Four studies (including the previously discussed Anderson 2009 study) focused on hospital readmission rates.

The first two involve work commissioned by industry associations. The methods used in these studies are not fully documented, making it challenging to assess them. With support from America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), Lemieux et al. (2012) found lower all-cause rates of readmission in Medicare Advantage compared to traditional Medicare from 2006‒2008. Because the data are proprietary (the MORE Registry), it is not clear which plans submitted data and how generalizable the findings are to different types of health plans and markets. While some use is made of the Jencks method to adjust for DRGs and descriptive tables are provided on points of interest, it is unclear if the research controls for differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare on geographic location, socio-demographic characteristics and health status/risk.9 Further, data on hospital readmissions do not distinguish between multiple readmissions of the same patient. The second study, Anderson (2009) as previously discussed, was supported by the America’s Community Health Plans. Anderson (2009) also looked at hospital readmission rates, finding them to be considerably lower among beneficiaries in ACHP Medicare Advantage plan members than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. This study also used the Jencks model to determine hospital readmissions within 30 days and hospitalizations and emergency department visits for “ambulatory care-sensitive conditions” (ACSCs), but it is unclear how else the data were adjusted. As noted above, this study included established integrated delivery systems and nonprofit plans whose experience may not necessarily generalize to other types of Medicare Advantage plans.

Friedman et al. (2012) also looked at readmissions, although it included data for only five states, limiting the study’s generalizability. Friedman et al. (2012) focused specifically on initial readmissions and found that after controlling for beneficiaries’ health status, beneficiaries in traditional Medicare were less likely than beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage to be readmitted to the hospital after discharge; the opposite conclusion was reached prior to controlling for beneficiaries’ health status, indicating that studies not controlling for health status could be biased in favor of Medicare Advantage plans. The study by Smith et al. (2005) came to similar conclusions, although the research focused only on patients in a single health plan who had strokes and used older data from 1998-2000. These studies seem to provide weak evidence at best that Medicare Advantage plans have lower rates of potentially avoidable hospital readmissions than does traditional Medicare.

Other Utilization Metrics (including HEDIS utilization metrics)

Table 7 reviews studies using three other sets of utilization metrics comparing Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare on end-of-life care, use of selected procedures, and overall utilization of services. As noted previously, these metrics, some included in HEDIS performance reporting, measure Relative Resource Use (RRU), the quality implications of which are hard to determine absent information on appropriateness of care to distinguish overuse from underuse or misuse.

Service use at end of life. Many believe that care at the end of life could be better with more focus on the total patient and their preferences, and doing so may result in savings by avoiding costly hospital stays and other care that offers limited benefits that patients and their families may not want.10 Medicare pays for hospice benefits the same way in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Specifically, Medicare Advantage enrollees who use hospice stay enrolled in their plan but Medicare (rather than the plan) pays directly for hospice benefits, as is done for beneficiaries using hospice in traditional Medicare.11

Stevenson et al. (2013) examined end-of-life care during the last calendar year of life from 2003‒2009, comparing service use for continuously enrolled elderly Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare HMOs versus the traditional Medicare program. Beneficiaries in Medicare HMOs were more likely to use the hospice benefit, although the difference in the use of the hospice benefit between Medicare HMOs and traditional Medicare narrowed between 2003 and 2009. Medicare HMO enrollees in their last year of life also used fewer inpatient and emergency room services, though researchers were limited in their ability to adjust for any differences in the medical conditions of beneficiaries in Medicare HMOs and traditional Medicare or for patient preferences that also could be reflected in choice of health plan or sector. Stevenson et al. (2013) suggest that their findings could mean that Medicare HMOs do a better job of managing end-of-life care. Thus, it is not clear from the research whether differences in end-of-life care reflect the characteristics of beneficiaries drawn to Medicare HMOs (such as those preferring a less intensive style of care), HMO care management practices (more emphasis on shared decision-making and two way communication), or potential incentives on Medicare HMOs because hospice benefits are “carved out,” and paid directly by Medicare though the individual remains an HMO member. (HMO payments may encourage hospice use because it could potentially lower the costs incurred by the health plan.) Unfortunately, appropriate norms for end-of-life care are both lacking and controversial and very little information is available about the studied beneficiaries, making it hard to assess how to interpret these findings from a quality perspective.

MedPAC (2014b) also found higher rates of hospice use and shorter hospice stays among Medicare Advantage enrollees than among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare (without controlling for case mix); differences in length of hospice stay, they noted, could be a function of differences in primary diagnoses. MedPAC (2014) expressed concern that that the hospice carve-out may result in more fragmented care because no one entity is responsible for the care of the beneficiary and recommended that hospice become part of the Medicare Advantage benefit package.

Use of selected procedures. Matlock et al. (2013) examined rates for three cardiac procedures for Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage plans participating in the Cardiovascular Research Network (CVRN) consortium (mainly older, established plans that use integrated networks), and compared them with demographically adjusted rates for the same procedures in traditional Medicare over the 2003-2007 period. Though coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) rates were similar in the two sectors, Medicare Advantage enrollees had on average lower rates of angiography and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI). The differences were driven more by procedures that were non-urgent than urgent, and thus reflect potentially more discretionary care. However, considerable variation existed geographically in each sector, and Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare rates in the same areas were not necessarily correlated, meaning that the differences probably reflect plan variation, not just area variation in practice patterns. Though the study included both inpatient and outpatient procedures, it did not adjust traditional Medicare data for beneficiary health conditions that could drive both plan choice and procedure use. While the findings suggest that care for some procedures is less intense in older, established HMOs than in traditional Medicare, the study’s implications for quality are uncertain in the absence of data on appropriateness of care to determine whether care is better in one sector than another.

Looking at an earlier period (1997 and just at HMOs), Schneider et al. (2004) also found variability in rates of high-cost procedures for HMOs of different types (adjusted for location and demographics), with nonprofit plans generally having lower rates of procedure use than for-profit HMOs. However, tax status was confounded with differences in plan age and model type. The study included both high- and low-discretion procedures and the appropriateness of procedure use could not be assessed.

Overall Utilization of Services. Three studies examined overall utilization of health services. Using data from 2003-2009 and controlling for self-reported health status, location and socio-demographics, Landon et al. (2012) found that elderly Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs had fewer emergency room visits and inpatient days in a hospital. Medicare Advantage enrollees initially also made fewer ambulatory visits and had fewer surgical days than those in traditional Medicare but these rates converged by the end of the period. HMO enrollees also had lower rates for certain ambulatory procedures (such as hip and knee replacements) but not others (such as CABG surgery and femur fractures). While the authors conclude that patterns of use show less use of discretionary care in Medicare Advantage, suggesting more appropriate care patterns, the findings seem to provide stronger evidence for a difference in resource use than quality of care across the two sectors and could also reflect uncontrolled differences in patient mix. Two other, older studies also showed lower use of inpatient services (Mello et al. 2002; Dhanani et al. 2005) after adjustments for differences in health status.

While these studies speak to differences in use of services in HMOs compared to traditional Medicare, their ability to speak to differences in quality is limited by the lack of information with which to judge appropriateness of care; in other words, it is not clear if use of fewer services is a positive or negative outcome. Because utilization data are available differently in Medicare HMOs (HEDIS use reports) and traditional Medicare (claims), reporting completeness and coding of service use also may differ.

Health Care Outcomes and Mortality

Seven studies examined the relationship between enrollment in Medicare HMOs or traditional Medicare and patient outcomes of three types: mortality rates, stage of cancer diagnosis and outcomes, and functional status (Table 8).

Mortality. Using data from the late 1990s, Dowd et al. (2011) compared two-year mortality rates between Medicare HMOs and those in traditional Medicare between 1996‒2000. While earlier studies seemed to show lower mortality rates in HMOs, Dowd’s analysis found no such effect after using econometric controls to predict and compare HMO and traditional Medicare mortality rates, adjusting for socio-demographics, health and functional status, smoking, and 19 self-reported conditions. This study’s findings lend support for the need to adjust for selection in assessing effects on health outcomes.

Stage of cancer diagnosis and outcomes. Five studies used public or private cancer registry data to assess how enrollment in Medicare health plans affects stage of diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes for various types of cancer. While one of these studies covers the 2005‒2007 period, the others tend to be older or straddle a longer time frame. While the studies were not focused solely on Medicare, they included estimates for Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare and deal with important outcome variables and so were included in this review. The insurance variables used in these studies differ from some other studies (for example, some separate out traditional Medicare only and traditional Medicare with supplemental coverage) and the definitions of some metrics are not entirely clear (e.g., how employment based retiree coverage factors into the definitions).

The study by Ward et al. (2010) was the broadest (registry data for malignant cancer in 14,000 U.S. facilities) as well as the most recent (2005 – 2007). It focused on the probability of late-stage cancer diagnosis based on insurance plan type for those 55 – 74 years of age. Its main finding was that insurance matters, with the uninsured and those on Medicaid (some of whom, researchers note, probably were uninsured for part of the year) more likely to be diagnosed late, and late diagnosis was correlated with survival. Within the Medicare population, researchers found little if any difference between beneficiaries in Medicare HMOs and those in traditional Medicare with supplemental coverage (though only about 5 percent of those 65 and older were in Medicare managed care). Beneficiaries with both Medicare and Medicaid and those with traditional Medicare alone were more likely to be diagnosed late. However the study did not adjust for health status.

The other studies had mixed results. Looking at elderly men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer, Sadetsky et al. (2008) found differences in treatment style but not on survival and clinical risk at diagnosis after applying statistical controls. Looking at Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed at ages 65 – 79 with prostate, female breast, or colorectal cancer in counties with Medicare managed care, Riley et al. (2008) found breast cancer diagnosed earlier in Medicare HMOs but no difference in stage of diagnosis for the other two cancers. However, treatment patterns for two of the three cancers differed between Medicare HMOs and traditional Medicare, with beneficiaries in HMOs on average using a less resource intense style, but considerable diversity in services use across HMOs. Adjustments for patient mix were limited, however. Looking at elderly Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed with melanoma, Kirsner et al. (2005) found that those in Medicare HMOs were diagnosed earlier, leading to improved survival rates. However the data were from 1985-1994 and were highly concentrated in the West Coast, where several large HMOs operate. It is unclear whether the findings apply to current conditions or to locales where managed care is less mature. Looking at colorectal cancer in northern California, Lee-Feldstein et al. (2002) used data from 1987 to 1993 and found earlier diagnosis among beneficiaries in non-group (i.e., IPA) HMOs and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental coverage than for those with other coverage (single-group HMO, dual eligible, or Medicare with no supplement). Survival rates were similar across groups, however, meaning in this context that earlier diagnosis did not affect survival.

Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that more comprehensive insurance probably increases the chances of early cancer diagnosis, and that health plan type may influence treatment but not necessarily outcomes. However, the age of the studies, the gaps in controls for selection, and the evolving nature of guidelines for appropriate care limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

Functional status. Only one study looked at differences between Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare using functional status as an outcome. Porell and Miltiades (2001), using data from 1991-1996, found that Medicare beneficiaries without a functional impairment who were in HMOs had the same probability of becoming disabled as beneficiaries in traditional Medicare; traditional Medicare beneficiaries with private supplemental insurance had a lower probability of becoming functionally impaired than those in traditional Medicare with no supplemental coverage. Once impaired, Medicare HMO enrollment status had no effect on beneficiaries’ functional status. However, the HMO sample was relatively small, and the study did not adjust for geographic locale.

Summary of Findings and Conclusions

This literature review included 45 studies published between 2001 and 2014 that examined how Medicare Advantage might affect health care quality and access to care, including 40 studies that made direct comparisons between Medicare health plans and traditional Medicare. As a body of work, these studies offer some insights, although the work is limited by shortfalls in the timeliness of data, the range of health plans studied and the comprehensiveness of the metrics available, particularly on a national basis. Recent studies still mainly capture the Medicare HMO experience rather than experience across the diversity of health plans now participating in Medicare Advantage, and none of them are current enough to provide insight on how Medicare Advantage compares to traditional Medicare after 2010. While many of the reviewed studies adjust for differences in location, patient mix, and health status between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in some fashion, some studies do this better than others, and many studies are constrained by limitations in the available data. In addition, few studies (only four) examine in depth the particular experience of those who are less healthy, functionally impaired, or have other characteristics that make them relatively high users of medical care and potentially disproportionately vulnerable to poorer quality of care or access problems.

The review of the literature, 45 studies published between 2000 and 2014, comparing quality of care and access provided under traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, suggests the following:

- HEDIS Effectiveness Metrics on Preventive Care. Medicare Advantage, on average, scores more highly than traditional Medicare on subsets of Medicare HEDIS indicators – primarily those pertaining to use of preventive care services. Two studies found Medicare preferred provider organizations (PPOs) outperformed traditional Medicare on some metrics (particularly mammography rates), though HMOs nevertheless performed better than PPOs. All of these studies were conducted prior to changes made by the ACA to improve coverage of preventive services under traditional Medicare.

- Beneficiary Reports on Quality and Access (CAHPS). Medicare beneficiaries generally rated Medicare Advantage lower than traditional Medicare on questions about health care access and quality, especially if beneficiaries had a chronic illness or were sick; however, the difference in ratings between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage narrowed on some metrics by 2009 (e.g., overall care ratings). Keenan et al. 2009 found that sick beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage rated their plans substantially lower than beneficiaries of similar health status in traditional Medicare, and Elliott et al. 2011 found significantly lower CAHPS ratings (and greater disparities between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare) among vulnerable subgroups of beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage. Little is known about how CAHPS scores vary by type of Medicare Advantage plan since most studies are based on HMOs or periods in which HMOs were the main plan type.

- Potentially Avoidable Hospital Admissions. Based on six studies involving beneficiaries in a limited number of states and/or plans represented by the Alliance of Community Health Plans (ACHP), Medicare beneficiaries in HMOs are less likely to be hospitalized for a potentially avoidable admission than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Four of these studies rely on data prior to 2006, and reflect HMO experiences in mature markets.

- Readmission Rates. While a number of studies examine whether readmission rates differ among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, the evidence from these studies is inconclusive because findings differ across the studies and many studies lack adjustments for important potentially confounding factors.

- Health Outcomes. There is some evidence that good coverage, as defined by relatively low cost-sharing (whether through Medicare HMOs or through Medicare with supplemental coverage), may result in earlier diagnoses of some cancers compared to traditional Medicare alone. Treatment patterns for some cancers also may differ between Medicare HMOs and traditional Medicare, but studies do not show that this affects patient outcomes. However, the age of the studies, the gaps in controls for selection, and the evolving nature of guidelines for appropriate care limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

- Resource Utilization. Medicare HMOs appear to provide a less resource-intensive style of practice than traditional Medicare, as measured in studies examining end-of-life care, use of certain procedures, and overall utilization rate in HMOs, especially for hospital services. However, most of these studies provide little direct evidence of whether less intensive care is better or worse or how the appropriateness of care differs between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.

- Variation by Geography, by Plan Type, and by Plan Experience. On a variety of metrics, performance among Medicare Advantage plans varies substantially across plans, even among plans of the same plan type. The variations by market in more established HMOs with integrated delivery systems tend to be more represented in existing research, and to perform better. Performance on quality and access metrics varies across geographic areas, and the variations in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare ratings are not necessarily the same.

In summary, despite great interest in comparisons between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, studies comparing overall quality and access to care between Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare tend to be limited.

On the one hand, the evidence indicates that Medicare HMOs tend to perform better than traditional Medicare in providing preventive services and using resources more conservatively, at least through 2009. These are metrics where HMOs have historically been strong. On the other hand, beneficiaries continue to rate traditional Medicare more favorably than Medicare Advantage plans in terms of quality and access, such as overall care and plan rating, though one study suggests that the difference may be narrowing between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage for the average beneficiary. Among beneficiaries who are sick, the differential between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage is particularly large (relative to those who are healthy). Very few studies include evidence based on all types of Medicare Advantage plans, including analysis of performance for newer models, such as local and regional PPOs whose enrollment is growing.

As the beneficiary population ages, better evidence is needed on how Medicare Advantage plans perform relative to traditional Medicare for patients with significant medical needs that make them particularly vulnerable to poorer outcomes. The ability to assess quality and access for such subgroups is limited because many data sources do not allow subgroups to be identified or have too small a sample size to support estimates. Also, in many cases, metrics employed may not be specific to the particular needs or the way a patient’s overall health and functional status or other comorbid conditions influence the care they receive for particular services.

At a time when enrollment in Medicare Advantage is growing, it is disappointing that better information is not available to support policymaking on this program. Our findings highlight the gaps in available evidence and reinforce the potential value of strengthening available data and other support for tracking and monitoring performance across Medicare Advantage plans and traditional Medicare as each sector evolves.

Works Cited

AHIP Center for Policy and Research. “Reductions in Hospital Days, Re-Admissions, and Potentially Avoidable Admissions among Medicare Advantage Enrollees in California and Nevada.” Washington: America’s Health Insurance Plans, (Revised) October 2009.[endnote 133466-1111]

AHIP Center for Policy and Research. “Using AHRQ’s ‘Revisit’ Data to Estimate 30-Day Readmission Rates in Medicare Advantage and the Traditional Fee-for-Service Program.” Washington: America’s Health Insurance Plans, October 2010.[endnote 133466-1112]

Anderson G. “The Benefits of Care Coordination: A Comparison of Medicare Fee-for-Service and Medicare Advantage.” Report prepared for the Alliance of Community Health Plans. September 2009.

Ayanian J et al. “Medicare Beneficiaries More Likely to Receive Appropriate Ambulatory Services in HMOs than in Traditional Medicare.” Health Affairs. 32(2013a): 1228-1235.

Ayanian J, Landon B, Zaslavsky A. Newhouse J. “Racial and Ethnic Differences in Use of Mammography Between Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare.” Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 105(2013b): 1891-1896.

Balsa AI, Cao Z, McGuire TG. “Does managed health care reduced health care disparities Between minorities and Whites?” Journal of Health Economics. 26(2007): 101-121.

Barnett MJ, Perry PJ, Langstaff JD, Kaboli PJ. “Comparison of rates of potentially inappropriate medication use according to the Zhan criteria for VA versus private sector Medicare HMOs.” Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy. 12(2006): 362-370.

Basu J. “Medicare Managed Care and Primary Care Quality: Examining Racial and Ethnic Effects across States.” Health Care Management Science. 15(2012): 15-28.

Basu J, Friedman B. “Adverse Events for Hospitalized Medicare Patients: Is There a Difference Between HMO and FFS Enrollees?” Social Work Public Health. 28(2013): 639-51.

Basu J, Mobley LR. “Do HMOs Reduce Preventable Hospitalizations for Medicare Beneficiaries?” Medical Care Research and Review. 64(2007): 544-567.

Beatty P, Dhont K. “Medicare Health Maintenance Organizations and Traditional Coverage: Perceptions of Health Care among Beneficiaries with Disabilities.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 82(2001): 1009-1017.

Bian J, Dow WH, Matchar DB. “Medicare HMO Penetration and Mortality Outcomes of Ischemic Stroke.” American Journal of Managed Care. 12(2006): 58-64.

Brennan N, Shephard M. “Comparing Quality of Care in the Medicare Program.” American Journal of Managed Care. 16(2010): 841-848.