Implementing Coverage and Payment Initiatives: Results from a 50-State Medicaid Budget Survey for State Fiscal Years 2016 and 2017

Vernon K. Smith, Kathleen Gifford, Eileen Ellis, Barbara Edwards, Robin Rudowitz, Elizabeth Hinton, Larisa Antonisse, and Allison Valentine

Published:

Executive Summary

Medicaid plays a significant role in the U.S. health care system, now providing health insurance coverage to more than one in five Americans and accounting for one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures.1 The Medicaid program continues to evolve as state and federal policy makers respond to changes in the economy, the broader health system, state budgets, and policy priorities, and in recent years, to requirements and opportunities in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). This report provides an in-depth examination of the changes taking place in Medicaid programs across the country. The findings in this report are drawn from the 16th annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors. This report highlights policy changes implemented in state Medicaid programs in FY 2016 and those implemented or planned for FY 2017 based on information provided by the nation’s state Medicaid directors. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report. Key findings include the following:

| Key Findings |

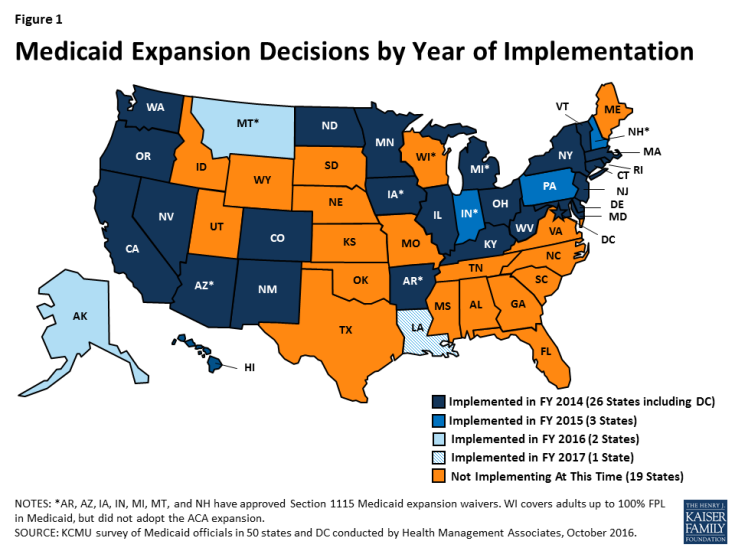

| Eligibility and enrollment. As of October 2016, 32 states had adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. Two states (Alaska and Montana) implemented the expansion FY 2016 and Louisiana implemented in FY 2017. Beyond the ACA, states made few major eligibility changes. Some states have approval or are seeking approval to impose premiums or monthly contributions under Medicaid expansion waivers. Many states have initiatives to expand coverage to the criminal justice involved population.

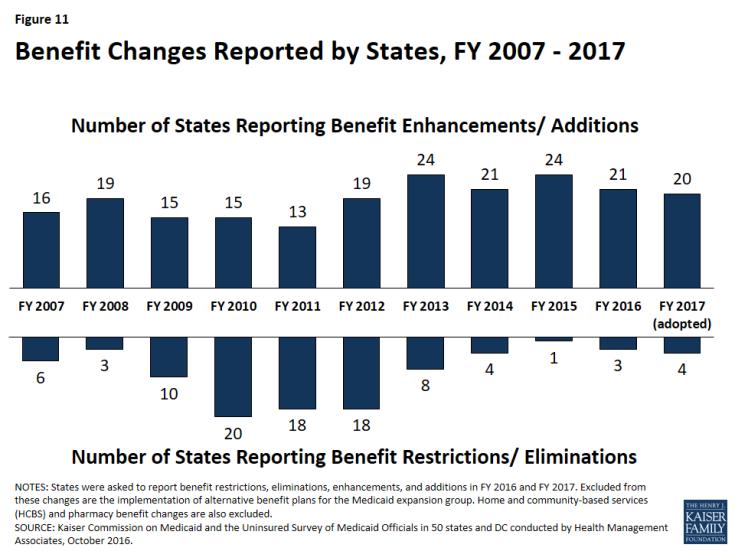

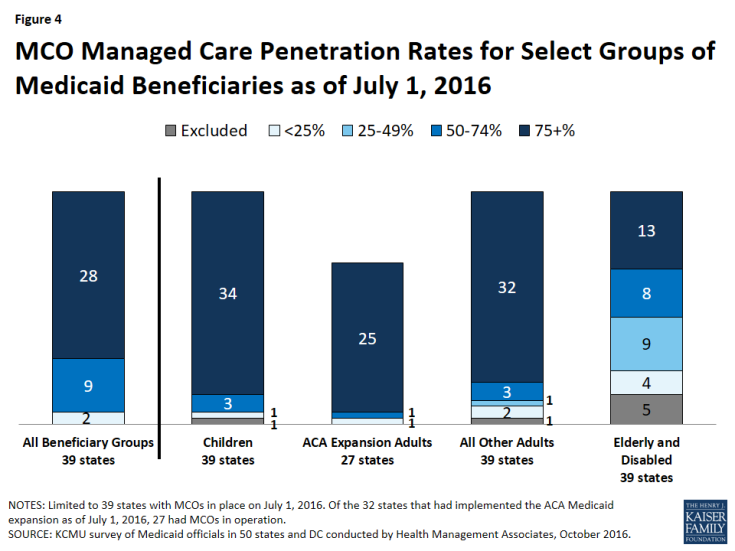

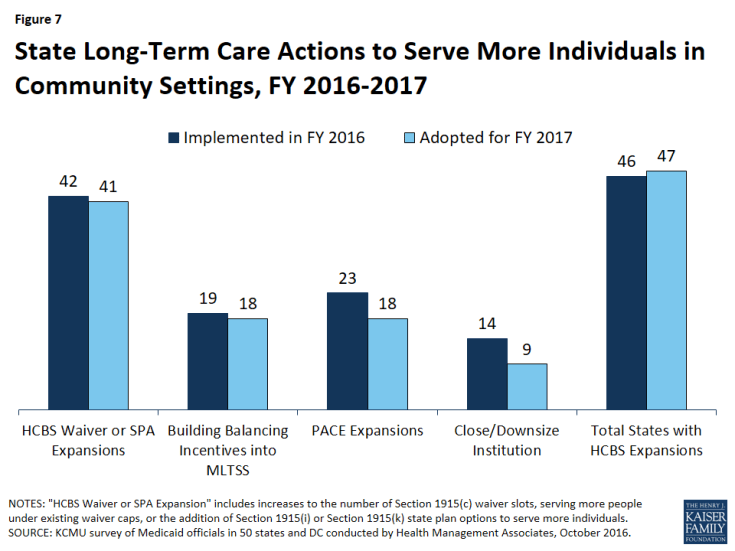

Managed care and delivery system reforms. In 28 of the 39 MCO states, at least 75 percent of all Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs. Many states are implementing quality initiatives such as pay for performance, reporting MCO quality metrics, or collecting adult and child quality measures. States are using MCO arrangements to promote value based payment and increase attention to the social determinants of health. Twenty-nine (29) states are also adopting or expanding other delivery system reforms in FY 2016 or FY 2017, such as patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), Health Homes, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) programs, and other efforts to better manage the care of high-need populations. Long-term services and supports (LTSS). Nearly every state reported actions to expand the number of persons served in community settings in FY 2016 and FY 2017, primarily through increased enrollment in HCBS waivers and implementing new HCBS SPAs. Twenty-three (23) states provided some or all LTSS through a managed care arrangement as of July 1, 2016, with 15 states offering MLTSS on a statewide basis for at least some LTSS populations. Provider payment rates and taxes. In FY 2016, more states implemented provider rate increases than implemented restrictions; however, as economic conditions become more challenged, slightly fewer states are implementing rate increases (40 states) than restrictions (41 states) in FY 2017. All states (except Alaska) use at least one provider tax or fee to help finance Medicaid. Eight of the Medicaid expansion states reported plans to use provider taxes or fees to fund all or part of the costs of the ACA Medicaid expansion beginning in January 2017, when states must pay 5 percent of the costs of the expansion. Benefits (including prescription drug policies). A total of 21 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in FY 2016, and 20 states are planning expansions for FY 2017, most commonly for behavioral health and substance use disorder services. With rising drug costs, 31 states in FY 2016 and 23 in FY 2017 reported implementing or plans to implement pharmacy cost containment efforts, some targeted to high cost specialty drugs. As part of the battle to address the nation’s opioid crisis, a majority of states have adopted, and many are expanding, pharmacy management strategies specifically targeted at opioids. Looking ahead. Many states report administrative challenges in implementing the ACA, major delivery system reforms, new federal regulations, and new systems due to limited resources in terms of staff and funding for administration. Despite the administrative and fiscal challenges, Medicaid directors listed priorities for FY 2017 and beyond that focus on payment and delivery system initiatives designed to control costs, improve access to care, and achieve better health outcomes. |

Eligibility and Enrollment

Medicaid expansion under the ACA continues to affect state policies for FY 2016 and FY 2017. As of October 2016, 32 states had adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. This includes 26 states that implemented the expansion in FY 2014, three states in FY 2015 (New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana), two states in FY 2016 (Alaska and Montana), and Louisiana in FY 2017. Beyond eligibility changes tied to the ACA, in FY 2016 and FY 2017 states implemented or adopted only a few changes generally targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries. Medicaid policies related to beneficiary premiums and copayments changed little overall; most of the activity reported related to Medicaid waivers. In FY 2016, Montana implemented a Medicaid expansion waiver that included provisions to impose premiums or monthly contributions. At the time of the survey, Arkansas, Arizona, Kentucky, and Ohio had Medicaid waivers pending with premium provisions. HHS denied Ohio’s pending waiver on September 9, 2016 and the Arizona waiver was approved on September 30, 2016.

Many states have initiatives to expand coverage to criminal justice involved populations. In states that implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, a greater proportion of this population is now eligible for Medicaid. Key initiatives include efforts to enroll individuals in Medicaid prior to their release and policies that maintain Medicaid eligibility during incarceration by suspending rather than terminating Medicaid coverage.

Managed Care and Other Delivery System Reforms

States continue to expand the use of MCOs and other delivery system reform efforts with goals to control costs, improve access to care and care outcomes, and ultimately improve population health (Figure ES-1). Many of these initiatives are targeted to high-need populations.

Reliance on risk-based managed care continues to grow as additional states use Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to deliver care or enroll more populations. As of July 2016, 39 states contracted with risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs) to serve their Medicaid enrollees. (These states are referred to throughout the report as “MCO states.”) In 28 of the 39 MCO states, at least 75 percent of all Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs (an increase from 21 of 39 states in July 2015). Three states (Iowa, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) terminated their Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) programs in either FY 2016 or FY 2017 and shifted those populations into risk-based managed care. Alabama plans to implement a new MCO program in FY 2017 and Missouri plans to expand its MCO program statewide in FY 2017.

States sometimes exclude special populations and/or some behavioral health services from MCO contracts. This survey asked about populations with special needs that may be included or excluded from acute care MCO enrollment. States reported that of the special populations noted in the survey, pregnant women were most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis into acute care MCOs (28 states) while persons with intellectual or developmental disabilities (ID/DD) were least likely to be enrolled on mandatory basis (10 states) and also most likely to be excluded from MCO enrollment (7 states).

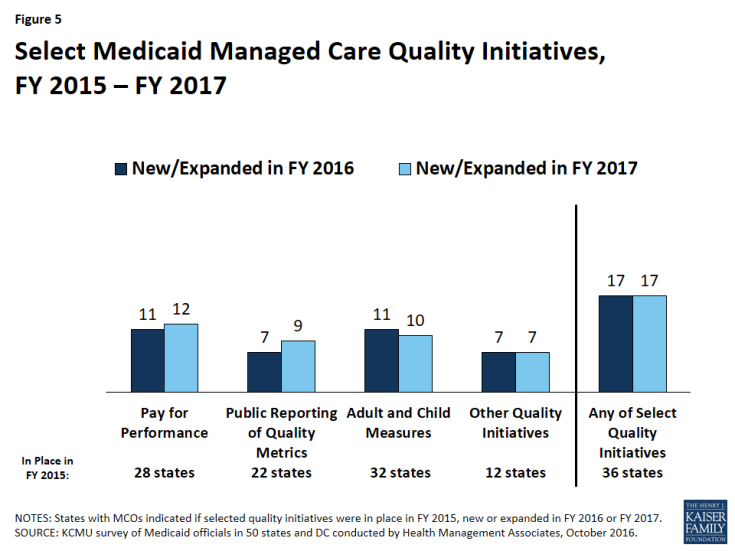

Many states are implementing quality initiatives encouraging or requiring MCOs to implement alternative payment models or screen for social needs. Thirty-six (36) of the 39 MCO states reported one or more select MCO quality initiatives in place in FY 2015 and 17 states in each of the survey years (FY 2016 and FY 2017) implemented or adopted new quality initiatives such as pay for performance, reporting MCO quality metrics or collecting adult and child quality measures. In FY 2016, five states identified targets in MCO contracts for the use of alternative provider payment models; 10 additional states intend to do so in FY 2017. States are also using MCO arrangements to increase attention to the social determinants of health. Twenty-six (26) states reported requiring or encouraging MCOs to screen for social needs and provide referrals to other services in FY 2016 and four states intend to do so in FY 2017. States commonly require MCOs to perform a health needs/risk assessment that includes information on social determinants as well as medical needs. In addition, five states reported that they have policies in place to encourage or require MCOs to provide care coordination services to enrollees prior to release from incarceration (Arizona, Iowa, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Ohio), and 10 states intend to add such requirements in FY 2017.

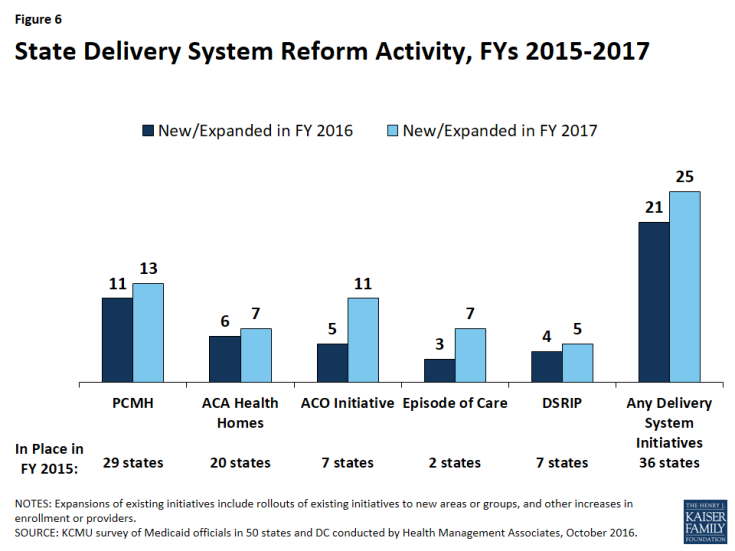

Over two-thirds of all states (36) have at least one delivery system or payment reform initiative in place and the majority of states are expanding current programs or adopting new initiatives. Twenty-nine (29) states in either FY 2016 or FY 2017 reported adopting or expanding one or more initiatives including patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs), Health Homes, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), and other initiatives to better manage the care of persons with multiple chronic conditions. Interest in Episode of Care initiatives also ticked upward for FY 2017 (7 states). These initiatives may be implemented through fee-for-service or managed care. Seven states had Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) programs in place in FY 2015. Four states reported new or expanded DSRIP programs in FY 2016 and five states reported new or expanded DSRIP programs in FY 2017.

Long-Term Services and Supports

Nearly every state reported actions to expand the number of persons served in community settings in FY 2016 and FY 2017, primarily through increased enrollment in HCBS waivers and implementing new HCBS SPAs. New PACE sites or expanded enrollment in existing PACE sites as well as including specific rebalancing incentives into managed care contracts that cover long-term services and supports (LTSS) were also strategies to increase community-based care.

Twenty-three (23) states provided some or all LTSS through a managed care arrangement as of July 1, 2016. Fifteen (15) states offered managed LTSS (MLTSS) on a statewide basis for at least some LTSS populations. The most common model combines both acute care and LTSS in a single plan, providing a comprehensive approach to service integration. Five states offer a prepaid health plan that covers only Medicaid LTSS. In FY 2016, four states implemented MLTSS or expanded MLTSS to new parts of the state, and four states expanded MLTSS to new populations. In FY 2017, two states anticipate geographic expansion in MLTSS, while five states anticipate adding new populations to MLTSS. Enrollment into the MLTSS program is always mandatory for seniors in 13 of the 23 MLTSS states, for individuals who have full dual eligibility status in nine states, for nonelderly adults with physical disabilities in 12 states, and for individuals with I/DD in eight states. Thirteen (13) states with MCOs offering LTSS reported having LTSS quality measures in place in FY 2015. In FY 2016, a total of six states implemented new or expanded LTSS quality metrics; five states plan to expand quality measures for LTSS in FY 2017.

Provider Rates and Taxes

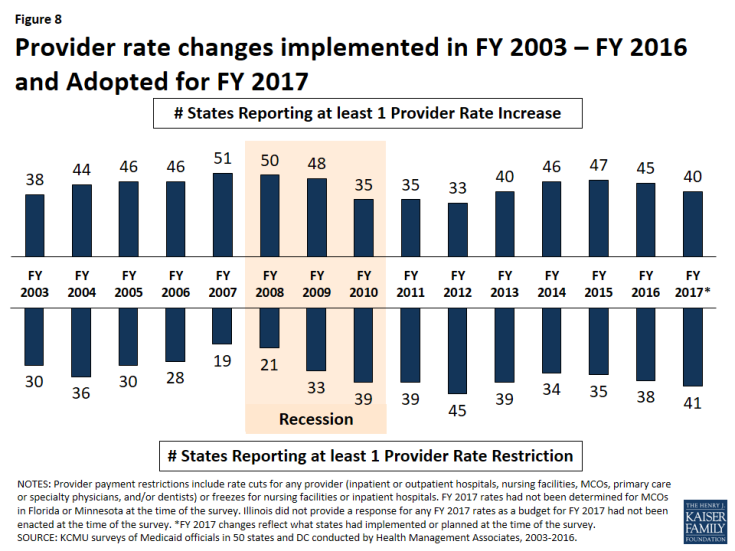

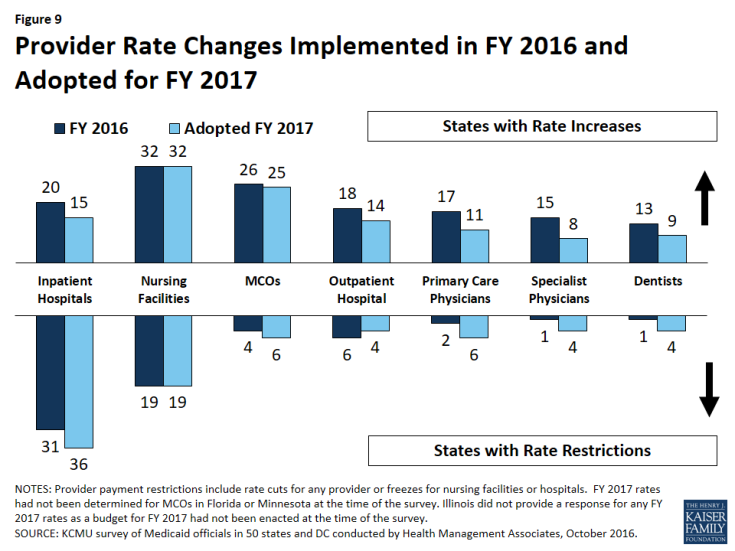

Changes in the economy continue to affect provider reimbursement rates, and states are also implementing reimbursement policies designed to promote quality. In FY 2016 more states implemented provider rate increases than implemented restrictions (45 and 38 states, respectively); however, as economic conditions become more challenged, slightly fewer states are implementing rate increases (40 states) than restrictions (41 states) in FY 2017. As part of efforts to improve the quality of health care and reduce costs, 21 states have or are adopting reimbursement policies in FY 2017 to reduce potentially preventable hospital readmissions in fee-for-service (FFS) and 11 of the 39 MCO states require or plan to require MCOs to adopt such incentives or penalties. Twenty (20) states have or are adopting reimbursement policies in FY 2017 designed to reduce the number of early elective deliveries in FFS and 14 states require or plan to require MCOs to adopt similar policies.

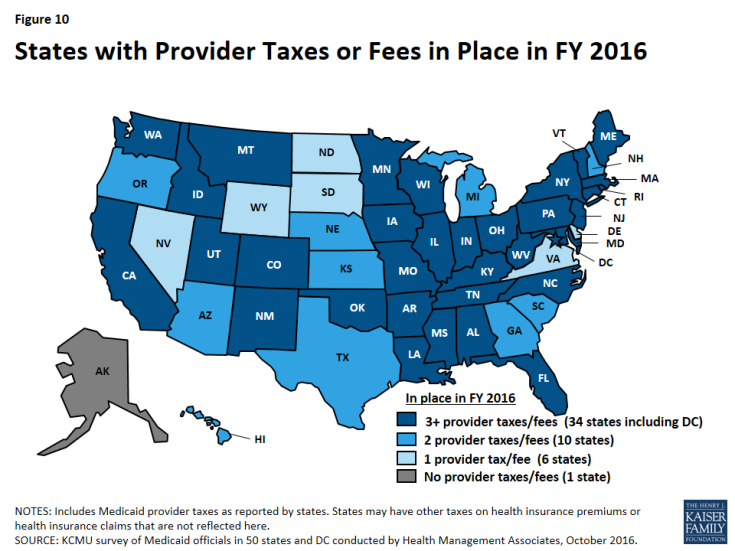

States continue to rely on provider taxes, with eight states using this financing mechanism to fund the state share of ACA expansion costs. All states except Alaska use at least one provider tax or fee to help finance Medicaid. In FY 2016 and FY 2017, 22 states increased or planned to increase one or more provider tax or fee and nine states are adding new provider taxes. Eight of the Medicaid expansion states (Arkansas, Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, New Hampshire, and Ohio) reported plans to use provider taxes or fees to fund all or part of the costs of the ACA Medicaid expansion beginning in January 2017, when states must pay five percent of the costs of the expansion.

Benefits and Prescription Drugs

A total of 21 states expanded or enhanced covered benefits in FY 2016, and 20 states planned benefit expansions in FY 2017. The most common benefit enhancements reported were for behavioral health and substance use disorder services, telemedicine and tele-monitoring services, and dental services for adults. Far fewer states reported benefit restrictions.

With rising drug costs, many states are focused on pharmacy cost containment efforts. The vast majority of states identified high cost and specialty drugs as a significant cost driver for state Medicaid programs, most pointing specifically to hepatitis C antivirals. Many states are focused on refining and enhancing their pharmacy programs, including actions related to new and emerging specialty and high-cost drug therapies. A total of 31 states in FY 2016 and 23 in FY 2017 reported implementing or plans to implement pharmacy cost containment efforts. Thirty-three (33) of the 39 states with MCO contracts as of July 1, 2o16 reported that the pharmacy benefit was generally carved in, and another state reported plans to implement a full pharmacy carve-in in January 2017. States reported how they manage MCO pharmacy programs; in FY 2015, 13 states had uniform clinical protocols, 10 states had uniform prior authorization, and 10 states had uniform PDL requirements across fee-for-service and MCO programs. Many states reported expansions of these strategies in FY 2016 and FY 2017.

As part of the battle to address the nation’s opioid epidemic, a majority of states have adopted, and many are expanding, pharmacy management strategies specifically targeted at opioids. The CDC has developed and published recommendations for the prescribing of opioid pain medications for adults in primary care settings.2 Twenty-one (21) states reported adoption or plans for adoption in FY 2017 for their FFS programs. Of the 39 states with MCO contracts, 11 are requiring MCOs to adopt the CDC guidelines or are planning to do so in FY 2017. Many other states indicated these policies were under review for FFS and MCOs. States were also adopting strategies to expand access to naloxone, a prescription opioid overdose antidote that prevents or reverses the life-threatening effects of opioids. Almost all states reported specific opioid-focused pharmacy management policies. Imposing a quantity limit was the most common pharmacy management approach, used by almost all states (46) in FY 2015 for their FFS programs. Use of prior authorization (45 states), clinical criteria (42 states), and step therapy (32 states) were also widespread in FY 2015 for FFS. Significantly fewer states (12) reported having a requirement in place in FFS in FY 2015 for Medicaid prescribers to check their states’ Prescription Drug Monitoring Program before prescribing opioids to a Medicaid patient. Many states also reported MCO policies in place; however, it is unclear how many states require such policies.

Administration and Key Priorities for 2017 and Beyond

Medicaid provides health coverage for over one-fifth of all Americans and accounts for one-sixth of national health expenditures.3 Its administration involves complex systems, rules, and requirements. States indicated their most significant administrative challenges related to implementing the ACA, major delivery system reforms, new federal regulations, and new eligibility and IT systems. Medicaid directors noted that limited resources in terms of staff and funding for administration make it difficult to balance competing priorities and implement multiple significant initiatives. Despite the administrative and fiscal challenges, Medicaid directors listed an array of priorities for FY 2017 and beyond that focus on payment and delivery system initiatives designed to control costs and achieve better health outcomes.

Report

Introduction

Medicaid has become one of the nation’s most important health care programs, now providing health insurance coverage to more than one in five Americans, and accounting for over one-sixth of all U.S. health care expenditures.1 The Medicaid program continues to change, as policy makers in each state seek to improve their program, responding to changes in the economy, the broader health system, state budgets and policy priorities, and in recent years, to requirements and opportunities in the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as well as new guidance and regulations. In many ways, state Medicaid programs are national leaders in delivery and payment system initiatives designed to improve health care and outcomes, and to control health care spending.

This report examines the reforms, policy changes and initiatives that occurred in FY 2016 and those adopted for implementation for FY 2017 (which began for most states on July 1, 20162). The findings in this report are drawn from the annual budget survey of Medicaid officials in all 50 states and the District of Columbia conducted by the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (KCMU) and Health Management Associates (HMA), in collaboration with the National Association of Medicaid Directors (NAMD). This was the sixteenth annual survey, which has been conducted at the beginning of each state fiscal year from FY 2002 through FY 2017.3 (Copies of previous reports are archived here.)

The KCMU/HMA Medicaid survey on which this report is based was conducted from June through August 2016. The survey was sent to each state Medicaid director in June 2016. Directors and their staff provided data for this report in their written survey response and through a follow-up telephone interview. All 50 states and DC completed surveys and participated in telephone interview discussions between June and August 2016. The survey instrument is included as an appendix of this report.

The survey collects some data about Medicaid policies in place during a base year, but focuses on changes from year-to-year. For FY 2017, the survey includes policy changes implemented at the beginning of the year, or for which a definite decision has been made to implement during the fiscal year; it does not include policy changes under consideration but for which a definite decision on implementation has not been made. Medicaid policy makers know that policies adopted for the upcoming year are sometimes delayed or not implemented for reasons related to legal, fiscal, administrative, systems or political considerations, or due to delays in approval from CMS. The District of Columbia is counted as a state for the purposes of this report; the counts of state policies or policy actions that are interspersed throughout this report include survey responses from the 51 “states” (including DC). Key findings of this survey, along with state-by-state tables providing more detailed information, are described in the following sections of this report:

- Eligibility, Enrollment, Premiums, and Copayments

- Managed Care Initiatives

- Emerging Delivery System and Payment Reforms

- Long-Term Services and Supports Reforms

- Provider Rates and Taxes

- Benefits and Pharmacy

- Administrative Challenges, Priorities, and Conclusion

Eligibility, Enrollment, Premiums, and Copayments

| Key Section Findings |

Tables 1, 2, 3, and 4 at the end of this section include additional details on eligibility, premiums, and cost-sharing policy changes in FYs 2016 and 2017. |

Changes to Eligibility Standards

The ACA Medicaid expansion was one of the most significant Medicaid eligibility changes in the history of the program. As of October 2016, 32 states had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion: 26 states implemented the expansion in FY 2014; three states (Indiana, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania) in FY 2015; two states (Alaska and Montana) in FY 2016, and on July 1, 2016 (FY 2017), the expansion became effective in Louisiana (Figure 1). Beyond the Medicaid expansion, states implemented or adopted only a few eligibility changes generally targeted to a limited number of beneficiaries.

Coverage Transitions

As a result of new coverage pathways (including both expanded Medicaid coverage and the availability of Marketplace subsidies), some states eliminated Medicaid coverage for beneficiaries with incomes above 138 percent FPL (most of this activity occurred in FY 2014 and was covered in earlier surveys). In addition, some individuals who had qualified through more limited Medicaid eligibility pathways, such as those related to pregnancy, family planning, spend-down, and the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment (BCCT), could be eligible for more comprehensive coverage through income based pathways in states that adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion. Even with alternative coverage options, many states have maintained most limited coverage options, although enrollment through these pathways may have declined. Changes to coverage above 138 percent of the FPL or to limited pathway coverage in FY 2016 or FY 2017 are listed below. Because individuals have access to Medicaid through another eligibility pathway or to other coverage options, these changes are not counted as positive or negative eligibility changes, but as “no change” (Tables 1 and 2).

- In FY 2016, Connecticut reduced Medicaid parent eligibility levels from 201 percent FPL to 155 percent FPL; many parents previously eligible at the higher levels should be eligible for Marketplace subsidies.

- New Hampshire plans to phase out its BCCT pathway in FY 2017.

- Pennsylvania eliminated spend-down for parents and adults with disabilities over age 21 as part of its Healthy PA waiver, but reinstated this coverage in March 2016.

- Ohio eliminated its family planning waiver in FY 2016. Michigan closed its family planning waiver to new enrollment in April 2014 and officially ended the program June 30, 2016.

Other Eligibility Changes

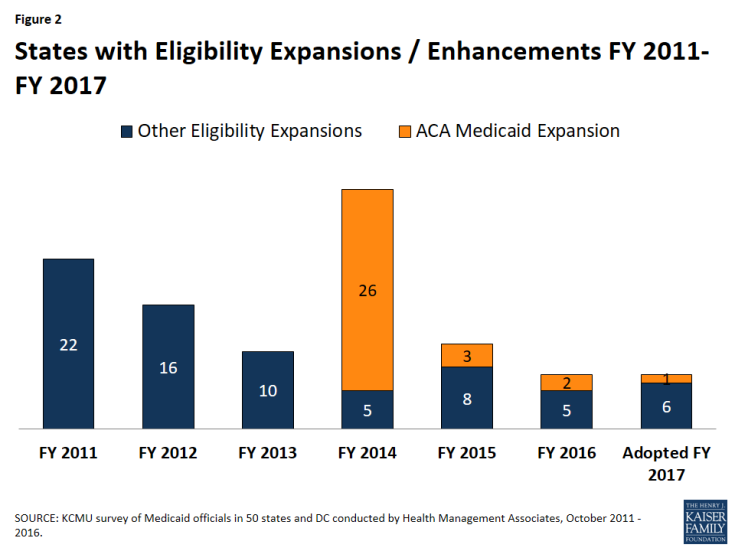

Other eligibility changes aside from the ACA expansion in FY 2016 and FY 2017 were limited and targeted to small numbers of beneficiaries (Tables 1 and 2). For FY 2016, a total of seven states made changes that expanded Medicaid eligibility and for FY 2017, seven states plan to implement Medicaid eligibility expansions (Figure 2). Key expansions include the following:

- Florida in FY 2016 and Utah in FY 2017 are implementing the option to eliminate the five-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for lawfully-residing immigrant children. Utah expects to cover an additional 750 children.

- Michigan implemented the Flint Water Group waiver, which extends Medicaid eligibility to children and pregnant women with incomes up to 400 percent FPL if they were exposed to tainted Flint water. (The waiver also expands benefits for existing eligible individuals by adding Targeted Case Management.)

- Maine will increase eligibility under its family planning pathway to 209 percent FPL in FY 2017.

Only two states in FY 2016 (Ohio and Virginia) and two states in FY 2017 (Arkansas and Missouri) made or plan to make eligibility restrictions. These are mostly targeted restrictions that would affect small groups of beneficiaries. Arkansas is seeking a modification to its “Private Option” waiver to, effective January 1, 2017, eliminate retroactive eligibility for expansion enrollees; the waiver is pending at CMS. Missouri plans to begin the process of suspending its family planning waiver in FY 2017 following legislative restrictions in the FY 2017 appropriations bill.1 The FY 2016 reduction in eligibility for waiver services in Virginia for seriously mentally ill individuals (GAP waiver program) was partially restored in FY 2017.

Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population

With the ACA Medicaid expansion to low-income adults, many individuals involved with the justice system are now eligible for Medicaid. Connecting these individuals to health coverage can facilitate their integration back into the community by increasing their ability to address health needs, which may contribute to greater stability in their lives as well as broader benefits to the individual and society as a whole. An increasing number of states have efforts underway to enroll eligible individuals moving into and out of the justice system into Medicaid. In April 2016 guidance, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) clarified that incarcerated individuals may be determined eligible for Medicaid and that the state Medicaid agency must accept applications and process renewals for incarcerated individuals.2 Although individuals may be enrolled in Medicaid while they are incarcerated, Medicaid cannot cover the cost of their care, except for inpatient services. In its recent guidance, CMS clarified who is considered an inmate of a public institution and therefore only able to receive Medicaid coverage for inpatient care.3 This survey asked states about a number of initiatives to promote Medicaid coverage for individuals involved with the criminal justice system (Exhibit 1 and Table 3).

The vast majority of states (44) had policies in place as of FY 2015 to obtain Medicaid reimbursement for inpatient care provided to incarcerated individuals who are Medicaid eligible. Four additional states implemented these policies in FY 2016 or plan to in FY 2017.

Given that the Medicaid expansion has significantly increased Medicaid eligibility among individuals moving into and out of the criminal justice system, many states are newly adopting or expanding initiatives to connect this population to Medicaid coverage. States are adopting policies to suspend Medicaid eligibility (rather than terminate eligibility) during incarceration. In FY 2015, 25 states had these policies in place for at least some individuals entering jail or prison, and 41 states are expected to have suspension policies by the end of FY 2017.

Medicaid and corrections agencies are also working together to help connect individuals to coverage as they are released from jail or prison back to the community. Some of these approaches include providing outreach and enrollment assistance pre-release, expedited enrollment processes for individuals being released, and Medicaid eligibility staff dedicated to processing applications for this population. A number of states have such initiatives in place and some states reported expanding these enrollment activities in FY 2016 or 2017. The most common expansions involve increasing the geographic scope of jail initiatives or increasing the number of prisons where eligibility assistance is provided.

The survey did not ask states about initiatives specific to parolees and individuals residing in halfway houses. However, Colorado, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia specifically mentioned initiatives to cover individuals residing in halfway houses.

|

Exhibit 1: Coverage Initiatives for the Criminal Justice Population

(# of States)

|

||||

| Select Medicaid Coverage Policies for the Criminal Justice Population | In Place in FY 2015 | New FY 16 or 17 |

Expanded FY 16 or 17 | In place/ planned for FY 2017 |

| Medicaid coverage for inpatient care provided to incarcerated individuals | 44 | 4 | 4 | 48 |

| Medicaid outreach/assistance strategies to facilitate enrollment prior to release | 31 | 11 | 13 | 42 |

| Medicaid eligibility suspended (rather than terminated) for enrollees who become incarcerated (jails OR prisons) | 25 | 16 | 3 | 41 |

| Arizona Medicaid and Corrections Policies |

| Arizona has implemented a number of strategies to increase coverage and access to care for the criminal justice population. The Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS), the state’s Medicaid agency, has agreements with most counties, including the two largest, and the Arizona Department of Corrections to allow for suspension of enrollment for jail and prison inmates. Arizona also provides support to counties to help them connect to the state’s eligibility system and facilitate enrollment and train community-based organizations, providers, and others on using the system for application assistance. The two most populous counties in the state have arrangements to provide enrollment assistance to persons on probation and throughout other areas of the system. The state also provides an expedited eligibility determination process for uninsured inmates with critical health needs who are scheduled to be released. Arizona has mandated that all Regional Behavioral Health Authorities have a designated liaison for coordinating care for persons with serious mental illness who are transitioning from the justice system. There is expedited review for individuals being discharged with a medical or behavioral health need so that care can be coordinated promptly. The state is also looking into ways to access data obtained through assessments as part of the probation process and other information that will help coordinate care. |

Medicaid Financed Births

For over three decades, Medicaid has been a key source of financing of births for low- and modest-income families. Women who would not otherwise be eligible can qualify for Medicaid coverage for pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum care due to higher income eligibility thresholds for pregnant women.4 Medicaid directors were asked to provide the most recent available data on the share of all births in their states that were financed by Medicaid. About half of states were able to provide data for calendar 2015 or fiscal year 2015.5 Other states generally provided data from 2013 or 2014. On average,6 states reported that Medicaid pays for just over 47 percent of all births. Eight states (Arkansas,7 Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and West Virginia) reported that Medicaid pays for 60 percent or more of all births in their state, while nine states reported that Medicaid finances less than 40 percent of all births (Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, Utah, Virginia, and Wyoming).

Premiums and Copayments

States have flexibility to charge limited premiums and cost-sharing in Medicaid, subject to federal parameters. Premiums are generally prohibited for beneficiaries with income below 150 percent FPL. Cost-sharing for people with income below 100 percent FPL is limited to “nominal” amounts specified in federal regulations, with higher levels allowed for beneficiaries at higher income levels. However, certain groups are exempt from cost-sharing, including mandatory eligible children, pregnant women, most children and adults with disabilities, people residing in institutions, and people receiving hospice care. In addition, certain services are exempt from cost-sharing: emergency services, preventive services for children, pregnancy-related services, and family planning services. Total Medicaid premiums and cost-sharing for a family cannot exceed 5 percent of the family’s income on a quarterly or monthly basis.8

Details about state actions related to premiums and copayments can be found in Table 4.

Premiums

Medicaid generally is not allowed to charge premiums to Medicaid beneficiaries with incomes at or below 150 percent FPL, although in limited cases certain populations, generally with income above 100 percent FPL, may be charged premiums (sometimes referred to as “buy-in” programs). Forty-four (44) states have buy-in programs for working people with disabilities and most of these states impose premiums.9 States also have the option to implement buy-in programs for children with disabilities. States that reported implementing premium-based programs under the Family Opportunity Act (FOA) for children with disabilities in families with incomes that otherwise exceed Medicaid limits include Colorado, Louisiana, North Dakota, and Texas.10 More recently, some states have received approval or were seeking approval to impose premiums under a Medicaid expansion waiver.

Seven states reported that they implemented or plan to implement new or increased premiums in FY 2016 or FY 2017 (Table 4). Three of these premium changes are related to individuals with disabilities. In FY 2016, Iowa increased Medicaid premiums for working people with disabilities. Two other states (Michigan in FY 2016 and Colorado in FY 2017) implemented or plan to implement expanded coverage and premiums for individuals with disabilities.

Five states (Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, and Montana) have received federal waivers to require premiums/monthly contributions for Medicaid expansion enrollees.11 In some cases, monthly contributions may be imposed in lieu of point-of-services copayments.12

Other implemented or proposed changes in premiums or contributions are for the Medicaid expansion populations.

- Montana implemented the Medicaid expansion in January 2016 under a waiver that requires monthly premiums up to 2 percent of household income for newly eligible adults from 51-138 percent FPL.

- Arkansas has waiver amendments pending that would take effect in calendar year 2017. The proposed waiver would replace the current income-based monthly contributions to “Health Independence Accounts,” which are to be used to fund copayments instead of paying at the point of service, with a premium requirement of 2 percent of income for those with incomes above 100 percent of FPL.

- Arizona had a waiver pending that would impose monthly premiums of 2 percent of income or $25, whichever is less, on all Medicaid expansion adults from 0-138 percent FPL, paid into health savings accounts. The waiver was approved on September 30, 2016 and allows for premiums at 2 percent of income for non-medically frail 100-138 percent FPL; individuals that comply with a healthy behavior program could have premiums eliminated for six months.

- Ohio submitted a waiver request in June 2016 to change its traditional expansion to the Healthy Ohio program which would impose monthly contributions, equal to the lesser of 2 percent of annual income or $99 per year, as a condition of eligibility for all beneficiaries except pregnant women and those with zero income. On September 9, 2016 CMS denied the state’s waiver request.

Kentucky has a waiver pending with CMS that would add premiums to its traditional Medicaid expansion program, along with other changes, but the proposed effective date is not until July 1, 2017 (FY 2018) so it is not captured in this report.

Copayment Requirements

- Five states reported new or increased copayment requirements for the Medicaid expansion population: Montana implemented new requirements in FY 2016, Louisiana plans to do so in FY 2017, Michigan plans to double copayments for Healthy Michigan Plan enrollees with incomes above 100 percent FPL in FY 2017, and New Hampshire planned copayment requirements for FY 2017 but these changes are included in waivers pending at CMS. The Ohio waiver that was denied would have increased copayments. The waiver approved in Arizona would allow for copayments (within state plan permissible levels) to be charged retrospectively for certain services such as non-emergency use of the emergency department, seeing a specialist without a referral, and use of brand name drugs when there is an available generic. Beneficiaries would get a quarterly invoice and be charged a monthly amount up to 3 percent of monthly income.

- In FY 2016, Indiana restored copayments for aged, blind, and disabled enrollees in managed care and Minnesota decreased copayment amounts for the Medical Assistance for Employed Persons with Disabilities (MA-EPD) group.

- In FY 2017, New Mexico plans to implement new copayments for non-emergency use of the emergency department for all Medicaid enrollees and new pharmacy copayments for all populations for brand name prescriptions when there is a less expensive generic equivalent available.13

- Four states are eliminating one or more copayment provisions in either FY 2016 or FY 2017 (North Dakota, New York, Oregon, and Vermont).

Table 1: Changes to Eligibility Standards in all 50 States and DC, FY 2016 and FY 2017

| Eligibility Standard Changes | ||||||

| States | FY 2016 | FY 2017 | ||||

| (+) | (-) | (#) | (+) | (-) | (#) | |

| Alabama | ||||||

| Alaska | X – Medicaid Expansion | |||||

| Arizona | ||||||

| Arkansas | X | |||||

| California | ||||||

| Colorado | X | X | ||||

| Connecticut | X | |||||

| Delaware | ||||||

| DC | X | |||||

| Florida | X | X | ||||

| Georgia | ||||||

| Hawaii | ||||||

| Idaho | ||||||

| Illinois | ||||||

| Indiana | ||||||

| Iowa | ||||||

| Kansas | ||||||

| Kentucky | ||||||

| Louisiana | X-Medicaid Expansion | X | ||||

| Maine | X | |||||

| Maryland | X | |||||

| Massachusetts | ||||||

| Michigan | X | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | |||||

| Mississippi | ||||||

| Missouri | X | |||||

| Montana | X – Medicaid Expansion | |||||

| Nebraska | ||||||

| Nevada | ||||||

| New Hampshire | X | |||||

| New Jersey | ||||||

| New Mexico | ||||||

| New York | ||||||

| North Carolina | ||||||

| North Dakota | ||||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | |||

| Oklahoma | ||||||

| Oregon | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | |||||

| Rhode Island | ||||||

| South Carolina | ||||||

| South Dakota | ||||||

| Tennessee | ||||||

| Texas | ||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | |||

| Vermont | X | |||||

| Virginia | X | X | ||||

| Washington | ||||||

| West Virginia | ||||||

| Wisconsin | ||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||

| Totals | 7 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

|

NOTES: Positive changes from the beneficiary’s perspective that were counted in this report are denoted with (+). Negative changes from the beneficiary’s perspective that were counted in this report are denoted with (-). Several states made reductions to Medicaid eligibility pathways in response to the availability of other coverage options (including Marketplace and/or Medicaid expansion coverage); these changes were denoted as (#) since most affected beneficiaries will have access to coverage through an alternative pathway.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2016.

|

||||||

Table 2: States Reporting Eligibility Changes in FY 2016 and FY 2017

| State | Fiscal Year | Eligibility Changes |

| Alaska | 2016 | Adults (+): Medicaid expansion on September 1, 2015 (estimated first year enrollment of 20,100). |

| Arkansas | 2017 | Adults (-): Pending waiver would eliminate retroactive eligibility for expansion population. |

| Colorado | 2016 | Children (+): Implement the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children (estimated to affect 1,699 children). |

| 2017 | Adults (+): Implementing annualized income for eligibility for other adults (affects 20,430 individuals). | |

| Connecticut | 2016 | Adults (#): Effective August 1, 2015 the income limits for HUSKY A parents and caretaker relatives were reduced from 201% FPL to 155% FPL. |

| DC | 2016 | Adults (#): Section 1115 Childless Adult waiver expired 12/31/2015. Adults with incomes from 133% to 210% FPL were transitioned from a Medicaid waiver to Medicaid state plan (8,500 individuals). |

| Florida | 2016 | Aged and Disabled (+): Increased the minimum monthly maintenance income allowance and excess standard for community spouses of institutionalized people. (The number of nursing facility residents eligible for Medicaid is also affected by 2016 cost of living adjustments and increases in the average private pay nursing facility used to set LTSS policy.)

Children (+): Implement the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children. |

| 2017 | Aged and Disabled (+): Increased the minimum monthly maintenance income allowance and excess standard for community spouses of institutionalized people. (The number of nursing facility residents eligible for Medicaid is also affected by 2017 cost of living adjustments and increases in the average private pay nursing facility used to set LTSS policy.) | |

| Louisiana | 2017 | Adults (+): Implemented Medicaid expansion on July 1, 2016 (375,000 individuals).

Adults (#): Effective July 1, 2016, 127,109 people covered in the Family Planning State Plan Amendment (SPA) were enrolled in the new Adult Group. The people remaining in the Family Planning SPA do not qualify for the Adult Group. |

| Maine | 2017 | Adults (+): Plan to increase eligibility under family planning pathway to 209% FPL in FY 2017. |

| Maryland | 2016 | Adults (#): Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program continued only for enrollees in active treatment (400 individuals). |

| Michigan | 2016 | Adults (#): Family planning waiver ended 6/30/2016.

Children & Pregnant Women (+): Flint Waiver Group Waiver extends Medicaid eligibility to 400% FPL for children and pregnant women exposed to tainted Flint water (up to 15,000 individuals). Aged & Disabled (+): Increased income and asset limits for working people with disabilities, effective 10/1/15. |

| Minnesota | 2017 | Aged & Disabled (+): Increased income standard for the medically needy from 75% FPL to 80% FPL on 7/1/2016. |

| Missouri | 2017 | Adults (-): Based on restrictions in the FY 2017 appropriation bill, Missouri will begin the process of suspending the Family Planning 1115 waiver. Expected transition 2/1/2017. |

| Montana | 2016 | Adults (+): Implemented ACA expansion via a waiver. Implemented 12-month continuous eligibility for newly eligible adults as part of the waiver. Effective 1/1/2016. |

| New Hampshire | 2017 | Adults (#): State legislation calls for ending the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program for new enrollees in FY 2017 while allowing current enrollees to continue treatment. |

| Ohio | 2016 | Adults (#): Ended Family Planning coverage group as of 1/1/16.

Other (-): Change in transitional Medicaid for families from twelve-months eligibility to six-months eligibility with possible coverage for two reporting periods. |

| 2017 | Aged & Disabled (#): Conversion from 209(b) to 1634 for SSI related groups. | |

| Pennsylvania | 2016 | Adults (#): Medically Needy Spend-Down for Parents and People with Disabilities was restricted to individuals under the age of 21 as part of Healthy PA implementation. However, it was reinstated in March 2016 and is once again available to these adults. |

| Utah | 2016 | Children (+): Medically Complex Children’s Waiver (165 children).

Children (#): Autism Waiver enrollment closed since autism services were added to the State Plan. |

| 2017 | Children (+): Implementing the CHIPRA option to eliminate the 5-year bar on Medicaid eligibility for legally-residing immigrant children (estimated to affect 750 children).

Adults (+): Proposed limited adult expansion: Parents of dependent children with incomes 40% to 60% FPL; adults without dependent children with incomes up to 5% FPL meeting certain criteria (9,000 to 11,000 individuals). |

|

| Vermont | 2016 | Aged & Disabled (+): Increased asset limits and income disregards for working people with disabilities (70 individuals). |

| Virginia | 2016 | Aged & Disabled (-): Reduced eligibility from 100% to 60% FPL for waiver services for people with serious mental illness (GAP waiver program). |

| 2017 | Aged & Disabled (+): Increased eligibility from 60% to 80% FPL for waiver services for people with serious mental illness (GAP waiver program). | |

| NOTE: Positive changes from the beneficiary’s perspective that were counted in this report are denoted with (+). Negative changes from the beneficiary’s perspective that were counted in this report are denoted with (-). Reductions to Medicaid eligibility pathways in response to the availability of other coverage options (including Marketplace or Medicaid expansion coverage) were denoted as (#). | ||

Table 3: Corrections-Related Enrollment Policies in all 50 States and DC, FY 2015-FY 2017

| States | Medicaid Coverage For Inpatient Care Provided to Incarcerated Individuals | Medicaid Outreach/Assistance Strategies to Facilitate Enrollment Prior to Release | Medicaid Eligibility Suspended Rather Than Terminated For Enrollees Who Become Incarcerated (Jails or Prisons) | |||||||||

| In place FY 2015 | New FY 16/17 |

Expanded FY16/17 | In place/planned for FY17 | In place FY 2015 | New FY 16/17 |

Expanded FY16/17 | In place/planned for FY17 | In place FY 2015 | New FY 16/17 |

Expanded FY16/17 | In place/planned for FY17 | |

| Alabama | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Alaska | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Arizona | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Arkansas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| California | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Colorado | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Connecticut | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Delaware | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| DC | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Florida | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Georgia | X | X | ||||||||||

| Hawaii | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Idaho | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Illinois | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Indiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Iowa | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Kansas | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Kentucky | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Louisiana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Maine | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Maryland | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Massachusetts | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Michigan | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Minnesota | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Mississippi | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Missouri | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Montana | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Nebraska | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Nevada | X | X | ||||||||||

| New Hampshire | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| New Jersey | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| New Mexico | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| New York | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| North Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| North Dakota | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Ohio | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Oklahoma | X | X | ||||||||||

| Oregon | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Pennsylvania | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Rhode Island | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| South Carolina | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| South Dakota | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Tennessee | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Texas | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Utah | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Vermont | X | X | ||||||||||

| Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Washington | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| West Virginia | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| Wisconsin | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Wyoming | ||||||||||||

| Totals | 44 | 4 | 4 | 48 | 31 | 11 | 13 | 42 | 25 | 16 | 3 | 41 |

|

NOTES: States were asked to indicate if any of the above corrections-related policies were in effect in FY 2015 and if they were newly adopted or expanded in FY 2016 or FY 2017. The “in place/planned for FY 2017” columns indicate states that either had a given policy in place as of FY 2015, newly implemented the policy in FY 2016, or plan to newly implement the policy in FY 2017. States with “Medicaid outreach assistance strategies to facilitate enrollment prior to release” include those with Medicaid led/coordinated efforts on outreach/enrollment assistance prior to release, expedited enrollment prior to release (e.g. presumptive eligibility), and/or Medicaid eligibility staff devoted to processing determinations prior to release.

SOURCE: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured Survey of Medicaid Officials in 50 states and DC conducted by Health Management Associates, October 2016.

|

||||||||||||

Table 4: States Reporting Premium and Copayment Actions Taken in FY 2016 and FY 2017

| State | Fiscal Year | Premium and Copayment Changes |

| Arizona | 2017 | Premiums (New non-medically frail adults 100-138% FPL): Waiver approved September 30, 2016 would allow premiums of 2 percent of income for adults with incomes 100-133% FPL. Individuals that comply with a health behavior program could have premiums eliminated for six months.

Copayments (New non-medically frail adults 100-138% FPL): The approved waiver would allow for copayments (within state plan permissible levels) to be charged retrospectively for certain services such as non-emergency use of the emergency department, seeing a specialist without a referral and use of brand name drugs when there is an available generic. Beneficiaries would get a quarterly invoice and be charged a monthly amount up to 3% of monthly income. Premiums and copayments together would be limited to the 5% cap of household income per quarter. |

| Arkansas | 2017 | Premiums (New for expansion population): Pending “Arkansas Works” waiver amendments would replace current required contributions to “Health Independence Accounts” in lieu of point-of-service copayments with required monthly premiums of 2% of household income for individuals between 100 and 138% FPL |

| Colorado | 2017 | Premiums (New option for LTSS populations): Implement a Medicaid Buy-In program for 3 HCBS waivers (7/1/16). |

| Indiana | 2016 | Copayments (New): Restore copayments for ABD enrollees in managed care (Jan 2016). |

| Iowa | 2016 | Premiums (Increased): The premium for working people with disabilities is based on state employee health insurance premium which increased in 2016. Unknown for 2017. |

| Louisiana | 2017 | Copayments (New for expansion population): New cost-sharing requirements for the expansion population are the same as those in place for the rest of the Medicaid population. |

| Michigan | 2016 | Premiums (Increased): Premiums for the Freedom to Work population are now calculated using a percent of a beneficiary’s MAGI income (10/1/2015). |

| 2017 | Copayments (Increase): Increase in prescription, hospital, and office visit copays for Healthy Michigan Plan enrollees with incomes above 100% FPL. | |

| Minnesota | 2016 | Premiums (Decreased): Minimum premium for Medical Assistance for Employed Persons with Disabilities (MA-EPD) reduced (Sep 2015).

Copayments (Decreased): Decreased copayment amounts for MA-EPD group (Sep 2015). |

| Montana | 2016 | Premiums (New only for expansion population): Newly eligible adults between 51 and 138% FPL required to pay monthly premiums up to 2% of household income (1/1/2016).

Copayments (New for expansion population): Childless adults with incomes below 138% FPL and parents with incomes between 51% and 138% FPL (1/1/2016). Copayments (Neutral): Cost sharing for adults with incomes up to 50% FPL was standardized with some amounts increased and some decreased (6/1/2016). |

| New Hampshire | 2016 | Copayments (Increased): Pharmacy copayments for the expansion population (those above 100% FPL) are being increased from $1/$4 (generic/brand) to $2/$8 (Jan 2016). |

| 2017 | Copayments (New only for expansion population): Pending waiver would subject expansion population to copayments on some medical services. | |

| New Mexico | 2017 | Copayments (New for all populations): Copays for non-emergency use of the emergency department (1/1/2017 target date).

Copayments (New for all populations): Copays for brand-name prescriptions when there is a less expensive generic equivalent medicine available (1/1/2017 target date). |

| New York | 2016 | Copayments (Elimination): Exemption from Medicaid co-pays for members with incomes below 100% FPL, hospice patients, and American Indians/Alaskan Natives who have never received a service from IHS, tribal health programs, or under contract health services referral (10/1/15). |

| North Dakota | 2017 | Copayments (Elimination): Higher copayment for non-emergency use of the ER will be eliminated (1/1/2017). |

| Ohio | 2017 | Premiums (New and would apply to all Medicaid beneficiaries except pregnant women and individuals with zero income): Waiver request to impose monthly premiums (the lesser of 2% of income or $99 per year). CMS denied Ohio’s pending waiver in September 2016.

Copayments (Increase): Healthy Ohio 1115 waiver would increase copayments for all beneficiaries covered by the waiver at the maximum amounts allowable under federal law and copayments would be paid into a Health Savings Account and paid from that account at point of service. CMS denied Ohio’s pending waiver in September 2016. |

| Oregon | 2017 | Copayments (Elimination): Copayments are being eliminated for preventive services for all Medicaid groups (1/1/2017). |

| Vermont | 2017 | Copayments (Elimination): Remove copays for sexual assault-related services for all Medicaid groups (10/1/2016). |

| NOTE: New premiums or copayments as well as new requirements such as making copayments enforceable are denoted as (New). Increases in existing premiums or copayments are denoted as (Increased), while decreases are denoted as (Decreased) and eliminations are denoted as (Eliminated). | ||

Managed Care Initiatives

| Key Section Findings |

Tables 5 through 9 include more detail on the populations covered under managed care (Tables 5 and 6), behavioral health services covered under MCOs (Table 7), managed care quality initiatives (Table 8), and MLR (Table 9).

|

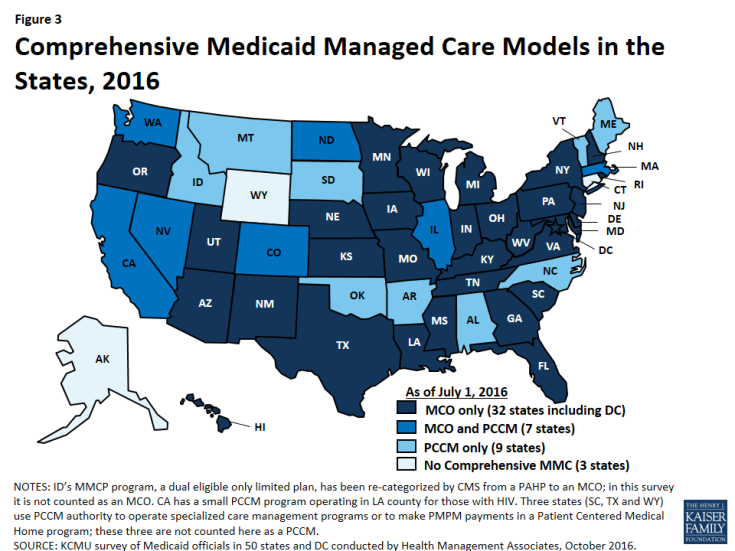

Managed care remains the predominant delivery system for Medicaid in most states. As of July 2016, all states except three – Alaska, Connecticut and Wyoming– had in place some form of managed care.2 Across the 48 states with some form of managed care, 39 had contracts with comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs), unchanged from July 1, 2015. Three states (Iowa, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) reported ending their Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) programs leaving 16 states that administered a PCCM program as of July 1, 2016, down from 19 states a year earlier. PCCM is a managed fee-for-service (FFS) based system in which beneficiaries are enrolled with a primary care provider who is paid a small monthly fee to provide case management services in addition to primary care.

Of the 48 states that operate some form of managed care, seven operate both MCOs and a PCCM program while 32 states operate MCOs only and nine states operate PCCM programs only3 (Figure 3). Wyoming, one of the three states without any managed care (i.e., without either MCOs or a PCCM program), does operate a limited-benefit risk-based prepaid health plan (PHP). In total, 24 states (including Wyoming) contracted with one or more PHPs to provide selected Medicaid benefits, such as behavioral health care, dental care, maternity care, non-emergency medical transportation, LTSS, or other benefits.

Populations Covered by Risk-Based Managed Care

The share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs or PCCM programs or remaining in FFS for their acute care varies widely by state. However, the share of Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in MCOs has steadily increased as states have expanded their managed care programs to new regions and new populations and made MCO enrollment mandatory for additional eligibility groups. The survey asked states to indicate the approximate share of specific Medicaid populations who receive their acute care in MCOs, PCCM programs, and FFS. As shown in Figure 4, among the 39 states with MCOs, 28 states reported that 75 percent or more of their Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in MCOs as of July 1, 2016 (up from 21 states in last year’s survey), including four of the five states with the largest total Medicaid enrollment. These four states (California, New York, Texas, and Florida) account for nearly four out of every 10 Medicaid beneficiaries across the country (Figure 4 and Table 5).4

Figure 4: MCO Managed Care Penetration Rates for Select Groups of Medicaid Beneficiaries as of July 1, 2016

Children and adults (particularly those enrolled through the ACA Medicaid expansion) are much more likely to be enrolled in an MCO than elderly Medicaid beneficiaries or those with disabilities. Thirty-four (34) of the 39 MCO states covered 75 percent or more of all children through MCOs. Thirty-two (32) of the 39 MCO states covered 75 percent or more of low-income adults in pre-ACA expansion groups (e.g., parents, pregnant women) through MCOs. The elderly and people with disabilities were the group least likely to be covered through managed care contracts, with only 13 of the 39 MCO states covering 75 percent or more such enrollees through MCOs (Figure 4).

Of the 32 states that had implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion as of July 1, 2016, 27 were using MCOs to cover newly eligible adults. (The five Medicaid expansion states without risk-based managed care were Alaska, Arkansas, Connecticut, Montana, and Vermont.) The large majority (25) of these 27 states covered more than 75 percent of beneficiaries in this group through risk-based managed care. The remaining two states, which reported less than 75 percent MCO penetration for this group, were Colorado and Illinois.

Seven of the 16 states with PCCM programs also contract with MCOs. In most of these states, MCOs cover a larger share of beneficiaries than PCCM programs. However, Colorado and North Dakota are exceptions: as of July 1, 2016, a majority of Colorado’s enrollees were in the PCCM program, which is the foundation of the state’s Accountable Care Collaboratives, and approximately half (49 percent) of enrollees in North Dakota were enrolled in the PCCM program.

Populations with Special Needs

This year’s survey also asked states with MCOs whether, as of July 1, 2016, certain subpopulations with special needs were enrolled in MCOs for their acute care services on a mandatory or voluntary basis or were always excluded. On the survey, states selected from “always mandatory,” “always voluntary,” “varies (by geography or other factor),” or “always excluded” for the following populations: pregnant women, foster children, persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (ID/DD), children with special health care needs (CSHCNs), adults with serious mental illness (SMI) and adults with physical disabilities. As shown in Exhibit 2 (and Table 6) below, pregnant women were the group most likely to be enrolled on a mandatory basis (28 states) while persons with ID/DD were least likely to be enrolled on mandatory basis (10 states) and also most likely to be excluded from MCO enrollment (7 states). Foster children were the group most likely to be enrolled on a voluntary basis (10 states) (although they were enrolled on a mandatory basis in a larger number of states).

Among states indicating that the enrollment approach for a given group or groups varied, geographic location and LTSS eligibility were the primary bases of variation. Six states (Colorado, Illinois, Missouri, Nevada, Utah, and Washington) specifically mentioned geographic variations and five states (Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Ohio, and Texas) mentioned variations based on LTSS eligibility (or “level of care”).

| Exhibit 2: MCO Enrollment of Populations with Special Needs, July 1, 2016 (# of States) |

||||||

| Pregnant women | Foster children | Persons with ID/DD | CSHCNs | SMI Adults | Adults w/ physical disabilities | |

| Always mandatory5 | 28 | 16 | 10 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Always voluntary | 1 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Varies (by geography or other factor) | 9 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 17 | 15 |

| Always excluded | 1 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

Acute Care Managed Care Population Changes

In both FY 2016 and FY 2017, states continued to take actions to increase enrollment in acute care managed care, although fewer states reported doing so than in the last two surveys (in 2014 and 2015) reflecting full or nearly full MCO saturation in a growing number of states. Of the 39 states with MCOs, a total of 16 states indicated that they made specific policy changes in either FY 2016 (11 states) or FY 2017 (11 states) to increase the number of enrollees in MCOs through geographic expansions, voluntary or mandatory enrollment of new groups into MCOs, or mandatory enrollment of specific eligibility groups that were formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis (Exhibit 3).

| Exhibit 3: Medicaid Acute Care Managed Care Population Expansions, FY 2016 and FY 2017 | ||

| FY 2016 | FY 2017 | |

| Geographic Expansions | IA, MS, UT | AL, CO, MS, MO |

| New Population Groups Added | CA, IA, LA, MS, NE, NY, WA, WV | AL, LA, NE, OH, RI, TX, UT, WV |

| Voluntary to Mandatory Enrollment | NH, RI, UT | |

Some of the notable acute care MCO expansions include:

- Three states (Iowa, Rhode Island, and West Virginia) terminated their PCCM programs in FY 2016 and shifted those populations into risk-based managed care. Iowa implemented statewide MCO coverage for almost all Medicaid enrollees on April 1, 2016 and ended its PCCM and behavioral health PHP programs.6 Rhode Island eliminated its PCCM program for adults with disabilities (Connect Care Choice) in FY 2016 and transitioned the enrollees to MCOs. West Virginia ended its small PCCM program and also transitioned its SSI population from FFS to mandatory MCO enrollment in July 2016.

- Alabama plans to implement mandatory MCO enrollment for nearly all Medicaid enrollees (currently served through PCCM and FFS) in FY 2017, although the state recently requested CMS approval to delay implementation until July 1, 2017.7 (Alabama’s fiscal year ends on September 30.)

- Missouri will extend its MCO program geographically statewide on May 1, 2017 for the populations eligible for managed care under current rules.

Geographic expansions of MCO service areas were reported in three states in FY 2016 (Iowa, Mississippi, and Utah), and in four states for FY 2017 (Alabama, Colorado, Mississippi, and Missouri).

In FY 2016 and FY 2017, states expanded MCO enrollment (either voluntary or mandatory) to additional groups. Some states added multiple groups. Some groups that states added or are planning to add include: foster care or adoption assistance children (Louisiana, Nebraska, Ohio, and Texas); persons eligible for LTSS (Nebraska, New York, and Washington); ACA expansion, newly eligible adult group (Louisiana and West Virginia); Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program group (Ohio and Texas); children with special health care needs (Louisiana and Ohio); pregnant women (California); Native Americans (Louisiana); children (Mississippi); SSI population (West Virginia); persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities (Ohio).

Three states made enrollment mandatory in FY 2016 for specific eligibility groups that were formerly enrolled on a voluntary basis: New Hampshire (dual eligibles, disabled children, and foster care children), Rhode Island (SSI), and Utah (enrollees in nine new mandatory counties).

Although outside the period covered by this survey report, Oklahoma reported plans to implement risk-based managed care for the aged, blind, and disabled population after FY 2017.

Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Behavioral Health Services Covered Under MCO Contracts

Although MCOs are at risk financially for providing a comprehensive set of acute care services, nearly all states exclude or “carve-out” certain services from their MCO contracts, most commonly behavioral health services. In this year’s survey, states with acute care MCOs were asked to indicate whether specialty outpatient mental health services, inpatient mental health services, and outpatient and inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) services are always carved-in (i.e., virtually all services are covered by the MCO), always carved-out (to PHP or FFS), or carve-in status varies by geographic or other factors.

For purposes of this survey, “specialty outpatient mental health” services mean services used by adults with Serious Mental Illness (SMI) and/or youth with serious emotional disturbance (SED), commonly provided by specialty providers such as community mental health centers. Depending on the service, about half of the 39 MCO states reported that specific behavioral health service types were carved into their MCO contracts, with specialty outpatient mental health services somewhat less likely to be carved in (Exhibit 4 and Table 7).

Of the nine states that indicated variation in the carve-in status of some behavioral health services, Texas and Washington cited geographic variation for all four service types; Ohio and Virginia indicated that outpatient mental health and SUD services were carved in only for dual eligibles in their Financial Alignment Demonstrations; Arizona reported that all four service types were carved out for children with a severe emotional disturbance; Missouri indicated variation based on diagnosis for children; New Jersey stated that inpatient medical detoxification services were always carved in while non-medical detoxification and short-term residential treatment for SUD were always carved out; South Carolina mentioned variation in specialty outpatient mental health services based on eligibility category, and also reported that psychiatric services in a freestanding hospital or dedicated unit are carved out, but psychiatric care during a hospital stay is carved in, and Wisconsin indicated that some specialty outpatient mental health services are carved in while others are carved out.

| Exhibit 4: MCO Coverage of Behavioral Health, July 1, 2016 (# of States) |

||||

| Specialty Outpatient MH | Inpatient MH | Outpatient SUD | Inpatient SUD | |

| Always carved-in | 20 | 24 | 24 | 26 |

| Always carved-out | 12 | 10 | 9 | 8 |

| Varies (by geography or other factor) | 7 | 5 | 6 | 5 |

Seven states in both FY 2016 (Arizona, Louisiana, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island, Washington, and West Virginia) and FY 2017 (Alabama, Nebraska, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Virginia and Washington) reported a new action to carve in, or plans to carve in, behavioral health services into their MCO contracts. Also, Wisconsin reported that, in an effort to promote care coordination, beginning in FY 2016, members receiving medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction are no longer exempt from managed care enrollment, except for continuity of care reasons.

Institutions for Mental Diseases (IMD) Rule Change

The recently finalized Medicaid Managed Care final rule8 allows states (under the authority for health plans to cover services “in lieu of” those available under the Medicaid state plan), to receive federal matching funds for capitation payments on behalf of adults who receive inpatient psychiatric or substance use disorder treatment or crisis residential services in an IMD for no more than 15 days in a month.9

States were asked in the survey whether they planned to use this new authority. Of the 39 states with MCOs plus Alabama (which plans to implement MCOs in FY 2017), 16 states answered “yes,” six answered “no,” and 18 states said a decision had not yet been made. Maryland said “no” but indicated that the state had applied for an IMD waiver to offer residential services for persons with an SUD diagnosis.

Additional Services

States with MCO contracts reported that plans in their states may offer a range of services beyond those described in the state plan or waivers. Twelve (12) states reported that MCOs in their states provide limited or enhanced adult dental services beyond contractually required state plan benefits. Nine states reported enhanced vision services for adults. Vermont reported enhanced mental health and substance use disorder services and the District of Columbia reported telemedicine for behavioral health services. States also reported a wide range of other extra services, including car seats, wireless cell phones or smart phone applications, gym memberships, smoking cessation supports, nutrition education, transportation, adult vaccines, health and wellness outreach centers, equine therapy, and Native American healing benefits. Some states (including Arizona and California) reported that MCOs are not required to report non-covered services to the state, but have the discretion to offer them when the plan judges an additional service to be beneficial and cost-effective. New Mexico allows MCOs to provide additional services, subject to state approval.

Managed Care Quality, Contracts Requirements and Administration

Quality Initiatives

States procure MCO contracts using different approaches. States may set a capitation rate that meets the test of actuarial-soundness and contract with any MCO willing to meet state and federal requirements. Most states now competitively bid for Medicaid MCOs, in part because the dollar value is so large – in some cases the largest procurement ever undertaken by the state. In these procurements, states can specify requirements and criteria that go beyond price such as value-based payments, specific policy priorities such as improving birth outcomes, or strategies to address social determinants of health, as well as specific performance and quality criteria. In this year’s survey, states were asked if they used, or planned to use, National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA’s) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS®) scores as criteria for selecting MCOs to contract with. Of the 39 states with MCOs, 14 answered “yes.”

After contracts are procured, all states with MCO programs track one or more quality measures and require other health plan activities to improve health care outcomes and plan performance. States were asked to indicate whether they had selected quality strategies in place in FY 2015, to establish a baseline, and also to indicate newly added or expanded initiatives in FY 2016 or FY 2017. Thirty-six (36) of the 39 MCO states reported one or more select MCO quality initiatives in place in FY 2015. The most common strategies were the collection of adult and child quality measures and pay for performance (Figure 5 and Table 8).

In FY 2016, 17 states implemented new or expanded quality initiatives and 17 states plan to do so in FY 2017 (Figure 5 and Table 8). Of the 39 MCO states, a total of 38 states in FY 2016 and all 39 states in FY 2017 will have at least one of these initiatives in place. The most common new quality initiatives were pay for performance and use of quality measures pulled from CMS’s core measure sets for adults and children (which are available but not mandatory for states to use).

States were also asked if capitation withholds in MCO contracts were in place in FY 2015, added in FY 2016, or planned for FY 2017. Twenty (20) states indicated withholds were in place as of FY 2015. States were also asked to specify what share of MCO capitation payments were withheld in FY 2016 and FY 2017. One state added a new MCO capitation payment withhold tied to quality performance in FY 2016 (Iowa) and three states intend to add a new MCO withhold in FY 2017 (Alabama, DC, and Oregon). Withhold amounts typically ranged from 1 percent (Massachusetts, Michigan, Texas, and Washington) to 5 percent (Georgia, West Virginia, and Minnesota). Tennessee reported using withholds in a range from 2.5 percent to 10 percent.

Contract Requirements

Alternative [Provider] Payment Models (APM) within MCO Contracts

Alternative provider payment models to advance value-based purchasing (VBP) strategies are a sharp focus of Medicaid programs, as states pursue improved quality and outcomes and reduced costs of care within Medicaid and across payers. Many states have included a focus on adopting and promoting alternative provider payment models as part of their State Innovation Models (SIM) projects, and some states have considered specifically how Medicaid MCOs can play a part in achieving improved accountability in the health care delivery system.10 The survey found that:

- Five states (Arizona, Delaware, Hawaii, Iowa, and South Carolina) identified a specific target in their MCO contracts for the percentage of provider payments, network providers, or plan members that plans must cover via alternative provider payment models in FY 2016; and

- Ten (10) additional states (California, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia) intend to include a target percentage in their contracts for FY 2017.

Further, 12 states had contracts that encouraged or required Medicaid MCOs to adopt alternative provider payment models in FY 2016, with eight additional states intending to encourage or require alternative provider payment arrangements within MCOs in FY 2017. The following box provides state examples of alternative provider payment targets.

| Alternative Provider Payment Targets |

|

Social Determinants of Health

In 2016, the CMS Center for Innovation announced a new Accountable Health Community model that represents the first CMS innovation model that focuses on social determinants of health. The goal of the five-year program is to raise awareness of and access to community-based services for Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries.11 This development reflects growing awareness and interest on the part of CMS to seek improved health outcomes and reduced costs by linking beneficiaries to social services and supports to address issues such as housing and food insecurity, among others, that can impact the ability of individuals to achieve health goals. States have also been focused on addressing social determinants of health, so federal and state activity are occurring simultaneously.

The survey found that 26 of the 39 states that contract with MCOs required or encouraged plans to screen enrollees for social needs and provide referrals to other services in FY 2016. Several states required MCOs to perform a health needs/risk assessment that includes information on social needs as well as medical needs. The following box provides state examples.

| Strategies to Address Social Determinants of Health |

|

Four states (Hawaii, Maryland, Nebraska, and New York) plan to require or encourage MCOs to screen and/or refer to social services and other programs in FY 2017. For example, Nebraska will require all MCO staff to be trained on how social determinants affect members’ health and wellness, including issues related to housing, education, food, physical and sexual abuse, violence, and risk and protective factors for behavioral health concerns.

Criminal Justice Involved Populations

Five of the 39 states with MCO contracts encourage or require MCOs to provide care coordination services to enrollees prior to release from incarceration (Arizona, Iowa, Kentucky, New Mexico, and Ohio), and 10 states intend to add such requirements in FY 2017. Ohio described a system in which pre-release care coordination is provided for enrollees with serious health conditions. An MCO care manager develops a care-focused transition plan to help facilitate access to needed services in the community, and a videoconference is conducted as a means to establish a relationship between the enrollee and the care manager. The care manager will follow up with the enrollee post-release to identify and remove barriers to care. Arizona noted that, in CY 2016, the requirement for pre-release care coordination services were limited to the behavioral health carve-out plan, but indicated that it would be extended to apply to all MCOs in CY 2017. In the letter approving the Arizona waiver on September 30, 2016, CMS said they would continue to work with Arizona on the delivery system reforms to integrate physical and behavioral health for Medicaid beneficiaries leaving the justice system.

While Florida does not require MCOs to provide pre-release care coordination, the state has a multi-agency project in place to implement pre-release care coordination to incarcerated Medicaid enrollees.

Administrative Policies

Minimum Medical Loss Ratios