Key Issues in Long-Term Services and Supports Quality

2017 marks the 30th anniversary of the passage of the Nursing Home Reform Act as part of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987, the federal legislation that substantially strengthened federal standards, inspections and enforcement of nursing home quality. The Act also merged Medicare and Medicaid standards, required comprehensive assessments of residents, set minimal requirements for licensed nursing staff, and required inspections to focus on outcomes of care.1 While progress has been made, care quality issues in nursing homes and residential care facilities2 (also called assisted living) continue to be highlighted frequently in the press3 and by numerous government reports4 and research studies5 (see Appendix Table 1). Recurring concerns include staffing levels, abuse and neglect, unmet resident needs, quality problems, worker training and competency, and lack of integration with medical care. The last several decades also have seen a shift to home care and other community-based services, with few quality measures for these settings available and little empirical evidence available.

This issue brief discusses four key issues related to long-term services and supports (LTSS) including institutional and home and community-based services (HCBS) quality, highlighting major legislative and policy changes over the last 30 years. The Appendix Tables provide data about LTSS providers and consumers, summarize key federal laws and policies related to quality, and list selected federal quality measures.

1. How is long-term services and supports quality regulated?

Federal quality standards exist for nursing homes, home health agencies and hospices, while states are responsible for regulating residential care, personal care, and other home and community-based services (Table 1). State health and social services agencies are primarily responsible for conducting the inspections and other monitoring of LTSS quality (with Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS) oversight where there are federal standards). Regular surveys are required more often (every nine to 15 months) for nursing homes, and less often (every three years) for hospices and home health agencies. Inspections also are conducted in response to complaints. Survey frequency for residential care, personal care and other home and community-based services (HCBS) providers varies by state, but is typically far less frequent than for nursing homes.

In addition, some federal quality measures exist for nursing homes, hospices, and home health agencies based on participant assessment data; comparable data does not exist for residential care facilities, personal care services and other HCBS. For example, many federal nursing home quality measures are based on the CMS Minimum Data Set (MDS), which contains data on comprehensive resident needs assessments reported quarterly.6 (See the Appendix for a detailed list of quality measures by service setting.)

CMS makes some quality survey information publicly available for nursing homes, hospices, and home health agencies, while dissemination of inspection data for most HCBS varies by state, but is rare. Detailed inspection data and penalties for violations for individual nursing homes are reported on CMS’s Nursing Home Compare website.7 Nursing homes also receive an overall quality rating using CMS’s Five Star Rating System, based on the annual on-site inspection and complaint investigation data provided by state agencies; facility-reported nurse staffing hours per resident day; and quality measures based on MDS resident data.8 In addition, some states have their own systems for issuing state deficiencies and fines,9 which are not included on the CMS website. CMS began posting quality measure scores for Medicare-certified hospices in 2017,10 but star ratings are not provided and federal inspection quality deficiencies are not publicly reported.11 Federal quality deficiencies, complaints, and intermediate sanctions are not reported on the CMS Home Health Compare website, which focuses on quality measures based on the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) assessment instrument and star ratings.12

| Table 1: Long-term services and supports Quality Monitoring by Provider Type | ||||

| Provider Type | Survey Entity | Frequency | Dominant Standards | Public Reporting |

| Nursing homes | State agencies under contract with CMS | Every 9 to 15 months | Medicare and Medicaid conditions of participation | CMS Nursing Home Compare/ Five Star Rating System |

| Hospices | State agencies under contract with CMS | Every 3 years | Medicare and Medicaid conditions of participation | CMS Hospice Compare |

| Home health agencies | State agencies under contract with CMS or private accrediting agencies | Every 3 years | Medicare and Medicaid conditions of participation | CMS Home Health Compare/Five Star Rating System |

| Residential care facilities | State agencies | Varies by state | State licensure and Medicaid requirements | Varies by state |

| Personal care and other HCBS providers | State agencies | Varies by state | State licensure and Medicaid requirements | Varies by state |

The Older Americans Act’s (OAA) state long-term services and supports ombudsman program works to resolve problems for residents in nursing homes and residential care facilities. New 2016 OAA amendments clarified that the program serves all long-term services and supports residents regardless of their age and includes residents transitioning to a home-care setting, residents unable to communicate their wishes or without an authorized representative, and residents and family councils. 13

2. What is the state of long-term services and supports quality today?

Nursing Homes

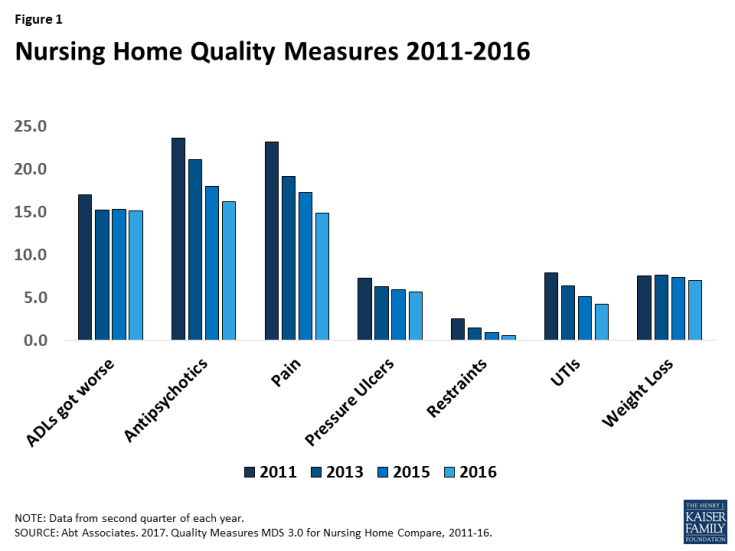

Most nursing home quality measures have improved over time (Figure 1). Between 2011 and 2016, the use of physical restraints declined from 2.5% to 0.6%, and pressure ulcers among high risk residents declined from 7.3% to 5.7%. Other measures, including the proportion of residents with activities of daily living that got worse, antipsychotic use, pain, and urinary tract infections, also showed improvements (by declining) over that period. Evidence suggests that these self-reported scores may be inflated by the nursing homes.14 In 2016, CMS added new quality measures from Medicare claims data that should be more accurate.15

Figure 1: Nursing Home Quality Measures 2011-2016

Many nursing homes, however, continue to fail to meet all federal quality standards, with about 93% receiving at least one inspection deficiency citation in 2015, about the same as in 2005. 16 Deficiencies are issued for violations of federal regulations in annual surveys and complaint investigations. The 15,583 nursing homes in the U.S. received 134,014 deficiencies, an average of 8.6 per facility, in 2015. This average rate is similar to that in 2005 and 2010.17 A 2014 US Office of Inspector General (OIG) report found that 33% of Medicare residents experienced adverse events or harm during their post-acute skilled nursing stays. Almost 60% of residents with adverse events had substandard treatment, inadequate monitoring, or failures and delays in treatment that resulted in harm, jeopardy, or hospital readmissions that cost about $2.8 billion.18 Another OIG study of nursing homes found that 25% of Medicare residents were readmitted to the hospital in 2011, at a cost of $14 billion; many readmissions were for potentially avoidable conditions.19

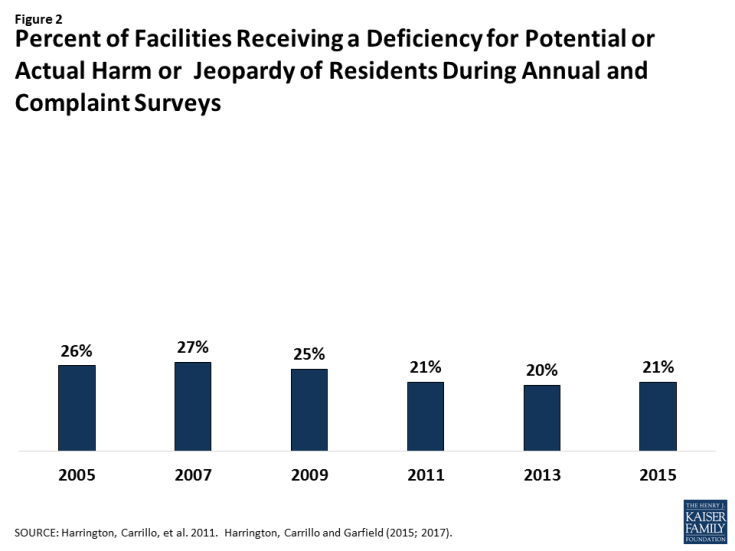

More than one in five (21%) nursing homes received deficiencies for serious quality violations in 2015, although this percent has declined over time (Figure 2). These deficiencies include causing harm or jeopardy, or the potential for harm or jeopardy, to residents and are based on state surveyor ratings of scope and severity.20 21 Between 2014 and 2016, serious quality violations resulted in 6,817 intermediate sanctions (penalties short of terminating participation in Medicare and Medicaid) against nursing homes, including $135.9 million in civil monetary penalties and denial of 44,113 Medicare/Medicaid payment days.22

Figure 2: Percent of Facilities Receiving a Deficiency for Potential or Actual Harm or Jeopardy of Residents During Annual Compliant Surveys

Nursing homes with high concentrations of minority residents tend to have more quality problems.23 More than a decade ago, researchers found that nursing homes with a higher percentage of black residents than white residents are located in the poorest counties and have fewer nurses, lower occupancy rates, and more quality deficiencies, compared to nursing homes with a higher percentage of white residents.24 These disparities have continued over time in nursing homes with high concentrations of minority residents.25

Non-profit nursing homes tend to have higher care quality than for-profit nursing homes. On average, non-profit facilities offer higher staffing ratios and higher quality care, compared to for-profit nursing homes, which spend less on labor and offer lower staffing ratios.26 The largest for-profit nursing home chains have the highest acuity residents, the lowest nurse staffing hours, and poorer quality measure scores compared with non-profit and government nursing homes.27 Non-profit nursing homes also have fewer 30-day hospital readmissions and greater improvement in resident mobility, pain, and functioning, compared to for-profit nursing homes.28

Higher nurse staffing levels generally are associated with better nursing home care quality. Reported registered nurse staffing and total staffing levels have steadily increased (from a total of 3.3 hours per resident day in 1995 to 4.1 hours per resident day in 2014).29 In spite of increases, a recent study documented that half of nursing homes have low staffing (3.53 hours per resident day or less), and at least a quarter have very low staffing (3.18 hours per resident day or less) compared to the minimum recommended levels of 4.1 hours per resident day.30 Over the past 25 years, more than 150 research studies have examined the effect of nurse staffing levels, particularly registered nurse staffing, on care outcomes, with most finding positive effects with higher staffing levels31 and improved quality outcomes in states with higher minimum staffing requirements.32 The benefits of higher staffing levels, especially of registered nurses, include lower mortality rates; improved physical functioning; less antibiotic use; fewer pressure ulcers, catheterized residents, and urinary tract infections; lower hospitalization rates; and less weight loss and dehydration.33 In addition to staffing levels, nursing staff training and competency have been identified as critical factors in ensuring high care quality.34

Federal nursing home staffing requirements have not changed since 1987,35 although research and experts support higher mandatory minimum staffing standards.36 Under the Nursing Home Reform Act, providers must have “sufficient staff” to meet resident needs with at least one registered nurse on the day shift and one licensed vocational or practical nurse on the evening and night shifts. A 2001 CMS study established the importance of having a total of 4.1 nursing hours per resident day, comprised of 1 .3 hours per resident day of licensed nursing care (including 0.75 registered nurse hours per resident day) and 2.8 certified nursing assistant hours per resident day, to prevent harm or jeopardy to residents.37 The effectiveness of these recommended thresholds was confirmed in an observational study38 and in a reanalysis by Abt Associates.39 A recent simulation study recommended a higher level of certified nursing assistant staffing, ranging from 2.8 to 3.6 hours per resident day depending on resident characteristics, to provide basic care to residents.40

Payroll reporting of staffing data may improve accuracy and monitoring of quality. A 2001 CMS study of nursing home staffing, which can affect care quality, found accuracy problems with self-reported unaudited data and recommended collecting data from payroll records.41 Mandatory electronic submission of nursing home staffing data based on payroll and other auditable records, as required by the Affordable Care Act,42 began on July 1, 2016, and CMS expects to add this information to Nursing Home Compare in 2018.43

Hospices

While federal quality standards exist, little is known about hospice care quality at least in part because federal surveys have been infrequent and quality reporting programs are new. Until passage of the federal IMPACT Act required surveys every three years, hospices were only surveyed every eight years. CMS has not made survey findings publicly available.44 The new hospice quality measures focus on: obtaining patient treatment preference information and managing pain and symptoms. Hospices have submitted patient admission and discharge data since 2014, and public reporting of quality measures on the CMS Hospice Compare began in August 2017.45 Six of the seven 2017 hospice measures show relatively little variation with average performance scores at 90 percent or higher. The pain assessment measure is an exception where only 78 percent of hospice patients received a comprehensive assessment within a day of experiencing pain.46 Because 6 percent of patients did not receive a visit in the last three days of life, CMS is developing new quality measures that focus on visits at the time or near the time of death.47 Concerned about the high number of voluntary discharges from hospice initiated by patients/families, CMS and RTI International are developing measures of potentially avoidable transitions and access to levels of hospice care.48 Similar to the racial disparities in care quality among nursing homes noted above, two studies found that hospices caring for more minority patients had significantly lower quality measure scores than those with smaller shares of minority patients even though minority hospice patients received similar care within the same hospice.49

Home Health Agencies

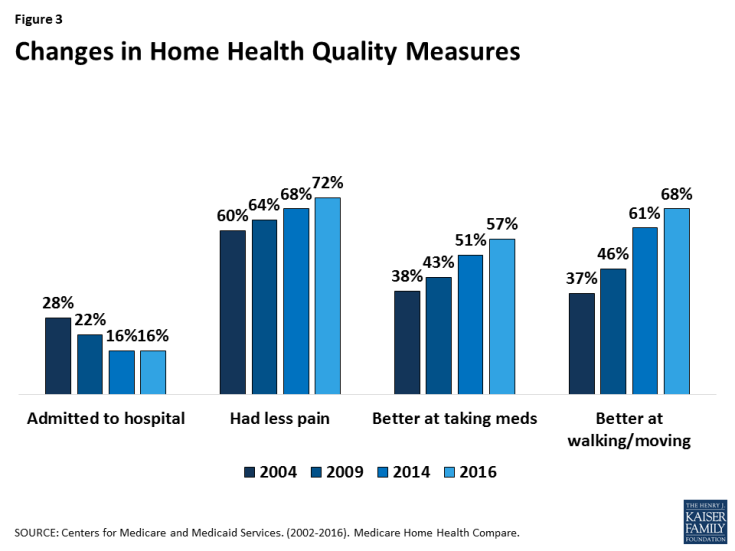

Home health quality measures generally have improved over time (Figure 3). Between 2004 and 2016, the percent of Medicare beneficiaries who were admitted to the hospital declined from 28% to 16%.50 During this same period, home health agencies reported more patients with less pain (60% in 2004 vs. 72% in 2016) and who were better at taking medications (38% vs. 57%) and at walking and moving (37% vs. 68%).51 The self-reported quality measures, however, may be inaccurate or inflated. CMS added new measures from claims data on hospital admissions and emergency room use to Home Health Compare in 2016.52 Data on federal deficiencies and sanctions of home health agencies from surveys are not made available by CMS as part of Home Health Compare.53

Figure 3: Changes in Home Health Quality Measures

Most national scores in the Home Health Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HHCAHPS) survey average around 80%. The average national HHCAHPS scores in 2016 ranged from 83-88% on four items: how often the home health team provided care in a professional way; how well the team communicated; whether the team discussed medicines, pain, and home safety; and patient rating of overall care. A slightly smaller share, 78%, reported that they would recommend the home health agency to friends and family.54

Although relatively little research has been conducted, home health agency quality appears to vary by ownership type. One recent study found that for-profit home health agencies have significantly lower overall quality measures than nonprofit agencies. 55 When risk-adjusted, non-profit agencies scored higher on care processes (e.g. team began care in a timely manner), care improvement (e.g. patients had less pain), hospitalization avoidance, and bedsore avoidance. For-profit agencies provided more visits and had more than double the profit margins compared to non-profits.56 Another study found that non-profit agencies were more likely to discharge patients within 30 days and appeared to be more efficient than for-profit agencies.57

Residential Care Facilities

Because quality standards vary by state and few data are publicly reported, little is known about residential care facility quality nationwide.58 Some states have their own searchable websites with quality information about residential care facilities.59 While not a survey of care quality, the 2010 National Survey of Residential Care Facilities identified some issues that may indicate quality problems. For example, during the course of a year, 15% of residents fell and sustained a hip fracture or other injury. 60 Among the 52% of residents who have cognitive impairment or dementia and behavioral symptoms, 61% had been prescribed medications to help control behavior or to reduce agitation. In addition, only half of residents left the facility grounds at least twice per month, even though residential care facilities are supposed to be community facilities.61 Available data about facility staff to resident ratios also raises questions about care quality. Larger facilities and chain facilities are more likely to have lower direct care staffing ratios than smaller facilities.62 Only 17% of residential care facilities reported having registered, licensed practical, or vocational nurses on staff.63 Residential care facilities are not required to provide licensed nursing on a 24-hour basis, even though there is evidence that many residents in some facilities are frail, with many chronic illnesses, impaired self-care and cognition, and unmet care needs.64

Personal Care Services and Other Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS)

Little is known about personal care and other HCBS quality because these services are regulated by the states and little data are collected and reported. Generally, consumers who use personal care services and those who have family members as care providers report high satisfaction.65 In 2014, CMS strengthened its quality requirements and reporting for the Medicaid HCBS waiver program in 14 areas (including administration, financial integrity, levels of care and provider qualifications and service planning and delivery).66 In addition, states must identify, address and seek to prevent instances of abuse, neglect, exploitation and unexplained death and must have an incident management system to effectively resolve and prevent incidents.67 These regulations also define what constitutes a setting that qualifies for Medicaid HCBS payments.68 A recent National Quality Forum report noted a: lack of standardized; limited access to timely HCBS program data: and variability in services (ranging from personal assistance to more skilled care) across the large number of programs, settings, and governmental jurisdictions and wide range of populations (including seniors, nonelderly adults, and children with a range of physical, developmental, and other disabilities).69 In spite of these challenges, a set of standardized core indicators were developed for states to voluntarily survey individuals who are aged and disabled across programs and some states conducted surveys in 2015 and 2016.70

3. What is not known about long-term services and supports quality?

Few federal measures assess quality of life in institutions and the home and community. Quality of life in nursing homes has long been a major concern. While federal regulations include resident rights, quality of life violations are often over shadowed (and not given sanctions) by the quality of care problems (e.g. safety and pressure ulcers) facing residents.71 Efforts to reimagine livable environments, services and quality of life are lacking. At home and in the community, quality of life is an important area to measure, although often a more complex inquiry than long-term services and supports, requiring new measures such as the number of individuals and the amount of spending in institutional vs. community settings.72 The degree of integration, independence and community access available to beneficiaries in different settings in the community are important measures. Measures could assess not only whether individuals are served in the community but also whether they are in the setting that affords them the fullest extent of community integration and independence, such as measures related to social activity and engagement.73

Quality data are unavailable at the provider chain or corporate owner level. With the wide variation in quality by nursing home ownership type and the growth of large chains with increasingly complex ownership structures, public interest in nursing home ownership transparency is growing. 74 While CMS recently began reporting some nursing home ownership data on Nursing Home Compare, quality data are not reported by nursing home chain and corporate owner, and details about parent, management, property, and other related companies are unavailable.75 Moreover, many home health agencies and hospices are part of large chains, and data on ownership and quality are not available by owner.76

Many HCBS quality measures are still being developed and lack standardization. Despite the general confidence that the quality of HCBS is good, few states have meaningful quality measures and data collection on provider performance to validate that belief. Many different organizations are using or testing a variety of questionnaires to measure HCBS quality.77 Although states are developing many new innovative long-term services and supports programs, standard HCBS quality measures have not been developed to allow comparisons across providers.78 A recent National Quality Forum report recommended developing and implementing a standardized approach to data collection, storage, analysis and reporting and developing a core set of standard HCBS measures with supplemental measures for different populations, settings and programs.79

The shift to capitated managed care delivery systems for Medicaid long-term services and supports services and supports80 creates both benefits and risks for service quality. In 2016, 721,000 individuals participated in the Medicare-Medicaid financial alignment initiative to integrate long-term services and supports with physical and behavioral health services, and many more are enrolled in Medicaid-only managed LTSS programs.81 Delivery systems that integrate physical, behavioral health, institutional, and community-based long-term services and supports offer the potential to improve quality through more holistic approaches to consumer needs and greater attention to the interaction between acute and long-term services and supports. Managed care delivery systems also raise the potential for adverse effects on care adequacy and quality if capitated payments incentivize health plans to limit spending by restricting services, reducing provider payments, or limiting provider networks.82

Without public reporting, the quality of LTSS provided in managed care organizations is unknown. Medicaid managed care regulations that for the first time address long-term services and supports services may promote the development of quality measures for HCBS. Effective for health plan contracts beginning on or after July 1, 2017, states must identify standard quality measures for Medicaid managed long-term services and supports health plans related to quality of life, rebalancing from institutional services to HCBS, and community integration.83 Because measures will be established by states, the potential for state variation will limit the ability to compare quality across states. Another unknown is whether managed care organizations will select networks of nursing homes, home health, hospice and HCBS providers on the basis of quality indicators rather than on the basis of location, costs or other factors.

4. What are the current challenges in long-term services and supports quality oversight?

Opportunities to improve quality oversight and enforcement of regulations by state and federal agencies have been identified. Since 1988, numerous investigations by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) have found that nursing home violations are under-identified, and serious violations are under-rated in terms of their scope and severity by state surveyors.84 The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) identified preventable quality problems as partly attributed to inadequate oversight by CMS and the failure of state survey agencies to enforce regulations.85 Consumer advocacy organizations also have voiced concerns that CMS has not focused sufficient efforts on survey and enforcement activities.86 CMS recently updated the nursing home conditions of participation and established a new process designed to address the well-documented variation in nursing home survey and enforcement activities across states.87 In addition, oversight of residential care facilities continues to be a concern in some states as problems of poor quality have persisted.88 Federal enforcement efforts for home health and hospice have been limited to date because of infrequent surveys and limited sanctions for violations. Little is known about state quality oversight of HCBS, and there is a concern that states may lack resources for inspection and enforcement.

Incidents of potential abuse and neglect of nursing home residents are not always reported to appropriate law enforcement and regulatory authorities.89 A new OIG report found that more than a quarter of incidents of possible abuse or neglect against nursing home residents go unreported to authorities despite the current mandatory reporting law. State survey agencies only substantiated 7 of 134 incidents of nursing home abuse or neglect in reports.90 This may also occur with other providers as well.

Complaints are not always investigated in a timely manner and are often not substantiated. Some state survey agencies do not meet CMS’s requirements for timely nursing home complaint investigations. These findings prompted the Government Accountability Office to recommend stronger federal guidance and oversight of the complaint investigation process.91 State complaint investigations for other providers may be even more limited, but no data are available.

Fines and other penalties for quality violations are rarely imposed, weakening enforcement. When nursing homes are found to have serious violations that caused harm or jeopardy including deaths, they often do not receive penalties or the penalties are so minimal that the enforcement does not result in compliance.92 Similarly, nursing homes operating with low staffing levels are rarely given deficiencies or penalties for inadequate staffing.93 In addition, nursing homes are seldom terminated from the Medicare and Medicaid programs as a result of quality violations.94 In response to complaints by the nursing home association, new 2017 CMS policies on penalties direct survey agencies to use per-instance penalties for problems that existed prior to a survey, except for serious injury or abuse, and per-day penalties for issues found during surveys and beyond. Consumer advocates argue this will make fines lower and less frequent.95 Since survey and enforcement information are not available for home health and hospice, it is unknown whether penalties have been imposed.

Binding arbitration agreements may be allowed. New 2016 CMS regulations eliminated arbitration agreements in nursing homes because of concern that it was difficult for residents and their decision-makers to give informed and voluntary consent.96 In 2017, CMS responded to nursing home provider complaints by proposing regulations to remove the prohibition against binding arbitration agreements in nursing home admission contracts, a move strongly opposed by advocacy organizations.97 It is not known whether such agreements are used by home health, hospice, and residential care providers.

Quality report card data are not adequately used by hospitals, health plans and consumers. After establishment of the CMS Nursing Home Compare rating system in 2008, nursing homes improved their scores on certain quality measures and consumer demand significantly increased for the best (5-star) facilities and decreased for 1-star facilities.98 A clinical trial of the use of a personalized version of Nursing Home Compare in the hospital discharge planning process found: greater patient satisfaction, patients being more likely to go to higher ranked nursing homes, patients traveling further to nursing homes, and patients having shorter hospital stays compared to the control group.99 In spite of the benefits of using report cards, a recent study found that most hospital patients receive only lists of nursing homes and do not receive data about nursing home quality. Patients’ choices were rarely based on quality data.100 Because discharge planners are not using CMS report cards for nursing home, it is doubtful that they are doing so when referring patients to home health or hospice. Report cards are lacking for residential care facilities and other types of HCBS.

Self-reported data by service providers raise questions about accuracy and may lead to under-reporting of indicators of poor quality. Nursing homes, hospices, and home health agencies have an incentive to under-report indicators of poor quality in order to receive higher quality ratings on the CMS Five-Star Quality Rating Systems to avoid scrutiny from surveyors.101 To address the potential for inflation in self-reported quality measure scores, CMS developed procedures for sample auditing of the accuracy of MDS nursing home data and associated quality measures.102 Similar concerns are associated with unaudited self-reported data by hospices and home health agencies as well as the data regarding ownership information and Medicare cost reports103 for nursing homes.104 Explicit reporting of costs, administrative costs, and profits by LTSS providers could be a useful addition to consumer report cards.105

Information about HCBS quality is lacking. As noted above, while government policy is vigorously moving to rebalance the delivery system away from institutions and toward HCBS, little data are available about the quality of residential care facilities, personal care, adult day health centers, or other types of HCBS. Quality measures need to be developed, and states would have to invest in inspections, surveys and other data collection in order to monitor the quality of services provided.

Looking Ahead

The 30th anniversary of the passage of the Nursing Home Reform Act provides an opportunity to reflect on accomplishments, challenges and future directions. Overall, there have been improvements in LTSS quality, although serious problems that jeopardize the health and safety of consumers continue to occur. Enforcement of existing regulations is an on-going concern for nursing homes, home health, and hospice, while states also face challenges to devote adequate resources to ensure quality in residential care and HCBS. Quality data that are self-reported by providers raise issues about how to ensure accuracy and reliability of information. Although important progress has been made in developing LTSS quality measures and public reporting, questions remain as to whether the information is being used sufficiently by hospitals and health plans as well as by consumers.

Federal legislation and regulatory standards for nursing homes are well-developed, and there have been improvements in nursing home quality over time. Nonetheless, more than 20% of nursing homes are cited for serious quality problems, and reports show that quality problems are under-reported because of a chronically weak survey and enforcement system. The quality problems created by low nurse staffing levels in many nursing homes are well documented. Disparities in care quality are associated with resident race/ethnicity, for-profit/non-profit status, and staffing levels. Problems with poor quality of care and quality of life in nursing homes may lead consumers to favor the use of home and community based services.

The quality of care in home health agencies has also improved, although about a quarter of Medicare patients would not recommend the agency that they used. Public reporting of quality measures for hospices is just starting. Even less is known about the quality of residential care, personal care, and other HCBS due to lack of inspections, quality measures, variation in oversight by states, and limited public reporting. Little is known about the impact of Medicaid managed LTSS programs and other integrated care systems on quality of LTSS.

Looking ahead, policymakers, researchers, consumers, and other stakeholders have identified opportunities to improve quality measures and monitoring processes for LTSS. New ways to facilitate comparisons across providers, programs and states and to increase the public dissemination of findings could assist stakeholders in better understanding LTSS quality.