Key Issues in Children's Health Coverage

| Key Takeaways |

|

This brief reviews children’s coverage today and examines what is at stake for children’s coverage in upcoming debates around funding for the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and restructuring of Medicaid financing to a block grant or per capita cap. Following decades of steady progress, largely driven by expansions in Medicaid and CHIP, the children’s uninsured rate has reached an all-time low of 5%. Medicaid and CHIP are key sources of coverage for our nation’s children, covering nearly four in ten (39%) children overall and over four in ten (44%) children with special health care needs. Medicaid serves as the base of coverage for the nation’s low-income children and covered 36.8 million children in fiscal year 2015. CHIP, which had 8.4 million children enrolled in fiscal year 2015, complements Medicaid by covering uninsured children above Medicaid eligibility limits. There is much at stake for children’s coverage in upcoming debates. New legislative authority is needed to continue CHIP funding beyond September 30, 2017. In addition, the Administration and Republican leaders in Congress have called for repeal and replacement of the ACA and restructuring of Medicaid financing to a block grant or per capita cap. Loss of CHIP funding, repeal of the ACA, and capping Medicaid financing all have the potential to reverse the coverage gains achieved to date and increase the number of uninsured children. In addition, rollbacks in coverage for parents could contribute to coverage losses among children and increased financial instability among families. Reductions in children’s coverage would lead to reduced access to care and other long-term effects for children and increase financial pressure on states and providers. Reductions in children’s coverage would result in fewer children accessing needed care, including preventive services such as well child visits and immunizations. Research also suggests that reductions in children’s coverage could have broader long-term negative effects on their health, education, and financial success as adults. In addition, loss of CHIP funding and reductions in federal Medicaid financing would create funding gaps that would increase financial pressure on states and providers. |

Introduction

Following decades of progress, bolstered by the ACA, the children’s uninsured rate has reached an all-time low. This brief reviews children’s coverage today and examines what is at stake for children’s coverage in upcoming debates around CHIP funding, repeal and replacement of the ACA, and restructuring of Medicaid financing to a block grant or per capita cap. Appendix Tables 1 and 2 provide state data on coverage for children and the number of children enrolled in Medicaid and CHIP.

Coverage for Children Today

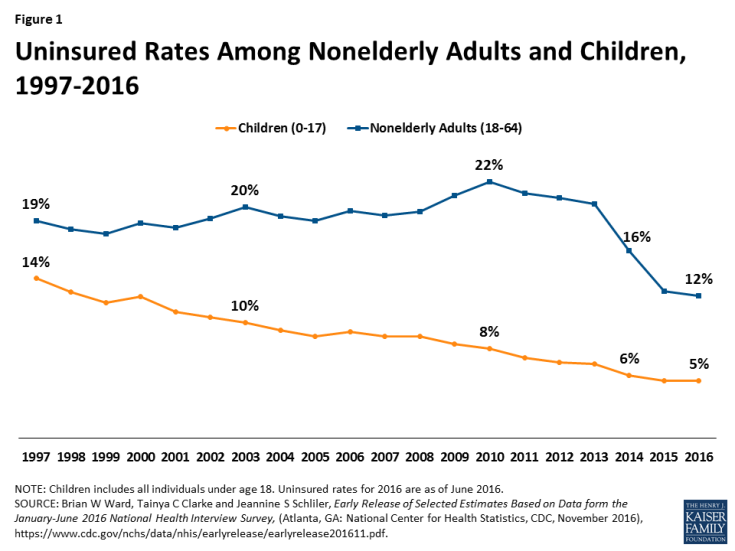

The uninsured rate among children has reached an all-time low of 5%. The uninsured rate among children has steadily decreased over time, with additional declines since implementation of the ACA in 2014. These coverage gains have stemmed from new coverage options for children through expansions of Medicaid and CHIP and the ACA Marketplaces and subsidies as well as from streamlining of enrollment and renewal processes and focused outreach and enrollment efforts. Children have had much larger gains in coverage than adults over the last two decades, largely reflecting the broader availability of Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children compared to adults (Figure 1).

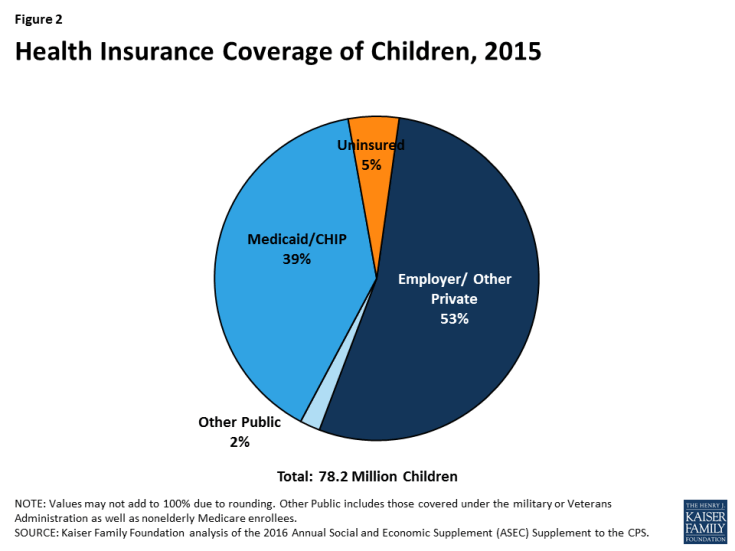

Medicaid and CHIP are key sources of coverage for our nation’s children. Today, over half of children are covered through private insurance, including parents’ employer-sponsored plans and individual market plans. Medicaid and CHIP cover nearly four in ten (39%) children overall and play a larger role for children with low incomes and special health needs. Together, the programs cover two-thirds (66%) of children in low-income families (below 200% of the federal poverty level, FPL) and more than three-quarters (76%) of children in poor families (below 100% FPL).1 Moreover, the programs cover more than four in ten (44%) of children with special health care needs.2 Despite consistent coverage gains over time, 5% or about 4 million children remain uninsured. Children’s uninsured rates range across states from a 2% in Illinois to 13% in Arizona (Appendix Table 1).3 Most uninsured children are eligible for Medicaid and CHIP, but not enrolled.4

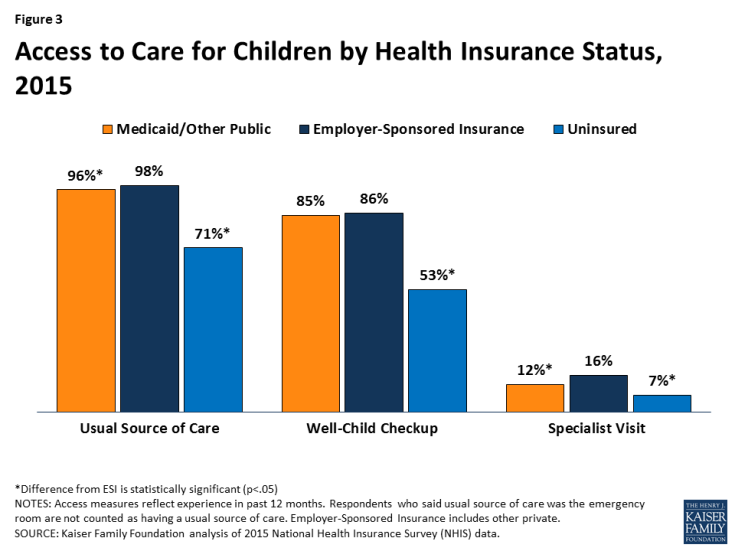

Health coverage provides children access to needed care and promotes improved health, education, and financial success over the long-term. Children with health coverage fare better on measures of access to care compared to uninsured children, and access for children with Medicaid and CHIP is comparable to access for children with private coverage along these measures (Figure 3). Studies also show that Medicaid and CHIP coverage contribute to long-term positive outcomes in health, school performance and educational attainment, and economic success.5 Moreover, parents say they are thankful for Medicaid and CHIP and have peace of mind knowing their children are covered.6 Polling data show that most adults (88%) would enroll a child in Medicaid if the child was eligible.7

The Role of Medicaid and CHIP for Children

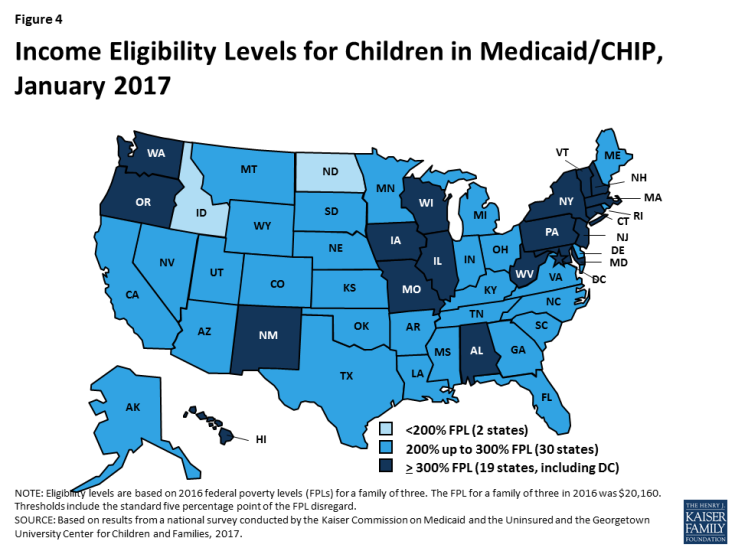

All states have expanded eligibility for children through Medicaid and CHIP. Medicaid is the base of coverage for our nation’s low-income children. CHIP complements Medicaid by covering uninsured children in families with incomes above Medicaid eligibility levels. States provide CHIP by creating a separate CHIP program, expanding Medicaid, or adopting a combination approach. The ACA built on previous Medicaid expansions for children by establishing a minimum Medicaid eligibility level of 138% FPL for children of all ages. Prior to the ACA, this minimum was already in place for children below age 6, but the minimum for children ages 6 to 18 was 100% FPL. As a result of this change, 19 states transitioned coverage for older children from separate CHIP programs to Medicaid.8 All states have expanded children’s eligibility beyond the minimum through Medicaid and CHIP. As of January 2017, 49 states extend Medicaid/CHIP eligibility for children up to at least 200% FPL (Figure 4).

Medicaid and CHIP provide broad benefits designed for children. Children enrolled in Medicaid are covered for all medically necessary care through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit. The benefit includes regular medical, vision, hearing, and dental screenings as well as the services necessary to “correct or ameliorate” physical or mental health conditions. Medicaid’s benefit package also includes long-term care services not typically covered by private insurance that help children with special health care needs remain at home with their families. The broad benefit package in Medicaid facilitates pediatricians’ ability to make treatment decisions for the children they serve. Moreover, the broad benefits help ensure children can access needed care, since families with children covered by Medicaid generally would not be able to afford services not covered by insurance. States have more flexibility around designing benefits in separate CHIP programs, but CHIP provides benefits designed for children’s needs, including dental care. Analysis shows that CHIP generally offers more comprehensive benefits at a much lower cost to families than private coverage.9

Premium and cost sharing protections in Medicaid and CHIP keep coverage and care affordable for low-income families. States generally are prohibited from charging premiums for children enrolled in Medicaid with family incomes under 150% FPL, and many children in Medicaid are exempt from cost-sharing. States have more flexibility to charge premiums and cost-sharing in separate CHIP programs compared to Medicaid. However, there are limits on costs that can be charged in CHIP, and analysis shows that CHIP is more affordable than employer-sponsored and Marketplace coverage.10 In focus groups, parents with children covered by CHIP say that they highly value the affordability of CHIP, that it is more important to them for their children to have coverage with comprehensive benefits and lower costs than to have their children in the same plan as them, and that they prefer to have their children in CHIP rather than private coverage because they would face higher costs with private coverage.11

Federal Medicaid and CHIP funding is central to supporting state capacity to cover low-income children. Under both programs, the federal government matches eligible state spending according to a formula that relies on states’ relative per capita income. To encourage participation among the states when CHIP was enacted in 1997, the federal government provided an enhanced (relative to Medicaid) matching rate for CHIP, which was further increased by 23 percentage points under the ACA. With this increase, the CHIP matching rate ranges from 88% to 100% across states.12 Under Medicaid, federal matching funds are guaranteed with no pre-set limits. Tied to this financing structure, Medicaid provides an entitlement to coverage and states are prohibited from imposing enrollment caps or waiting lists. In contrast, federal funds under CHIP are capped nationwide and each state operates under an allotment. Under separate CHIP programs, enrollees are not entitled to coverage and, at various times, states have imposed caps and waiting lists to limit CHIP spending. CHIP’s financing structure limits federal funding and makes federal funding more predictable, but it is not responsive to program needs, such as increased costs during economic downturns, and leads to challenges targeting funds and distributing funds across states.13

Key Issues at Stake for Children’s Coverage

New legislative authority is needed to continue CHIP funding beyond September 2017. Moreover, the Trump Administration and Republican leaders in Congress have called for repeal and replacement of the ACA and restructuring of Medicaid financing to a block grant or per capita cap. As debate in these areas unfolds, there is much at stake for children’s coverage.

Extension of CHIP Funding

New legislative authority is needed to continue CHIP funding beyond September 2017. As noted, unlike Medicaid, federal funding for CHIP is capped and provided as annual allotments to states. Since CHIP’s enactment in 1997, Congress has renewed federal funding for the program several times.14 Most recently, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) extended funding through fiscal year 2017. Without further Congressional action, CHIP funding ends this fiscal year on September 30, 2017.

Loss of CHIP funding could put children’s coverage at risk and increase financial pressures for states. In fiscal year 2015, 8.4 million children were enrolled in CHIP (Appendix Table 2); 4.7 million were in CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion programs, while the remaining 3.7 million were in separate CHIP programs.15 If CHIP funding ends, states would be required to maintain coverage for children in CHIP-funded Medicaid expansion programs under the ACA maintenance of effort requirement, and state costs for this coverage would increase since states would receive the lower federal Medicaid match rate. States would not be required to maintain separate CHIP coverage if funding ends. Some children in separate CHIP programs could shift to parents’ employer-sponsored plans or Marketplace plans, but others would become uninsured. The Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) estimates that if no new CHIP funds are provided, 1.1 million children would become uninsured.16

The implications of loss of CHIP funding would be even larger if combined with repeal of the ACA. If CHIP funding ends and Marketplace coverage is not available due to repeal of the ACA and/or the ACA maintenance of effort requirement is eliminated, coverage losses among children enrolled in CHIP could be even larger. The extent of further coverage losses would depend on what coverage may be available to these children under a replacement plan.

Given these potential risks and uncertainties, in January 2017, MACPAC recommended that Congress extend CHIP funding for five years, through 2022. MACPAC also recommended keeping the maintenance of effort requirement and 23 percentage point increase in the CHIP federal match rate through 2022. MACPAC notes that the extension would, “ensure that low- and moderate-income children retain access to affordable and comprehensive insurance coverage, maintaining the gain in coverage secured over the past 20 years.”17

Repeal of the ACA

Repeal of the ACA coverage expansions could lead to coverage losses for children. The ACA Marketplaces and subsidies provided a new coverage option for children in families who lack access to employer-based coverage and have incomes above CHIP eligibility levels. The ACA also expanded Medicaid eligibility for older children and contributed to increased enrollment among eligible children through new streamlined enrollment and renewal processes and outreach and enrollment efforts. Moreover, the ACA significantly increased coverage options for parents through its Medicaid expansion to adults up to 138% FPL (which 32 states, including DC, have implemented18) and the Marketplaces and subsidies. These coverage expansions for parents likely increased coverage among children, since research shows that children are more likely to be covered when their parent is covered.19 If the ACA coverage expansions were repealed along with the individual mandate, it is estimated that the number of uninsured children would increase by 4.4 million and the children’s uninsured rate would nearly double to just below 10% by 2019.20 However, the full extent of coverage losses would depend on what other coverage options might be available under a replacement plan.

Elimination of the ACA maintenance of effort provision could result in even larger coverage losses for children. The ACA protects existing coverage gains for children through a “maintenance of effort” provision that requires states to keep Medicaid and CHIP eligibility levels at least as high as those they had in place at the time the ACA was enacted through September 30, 2019. It is estimated that an additional 8.9 million children would be at risk for losing coverage if this requirement was eliminated and states reduced Medicaid and CHIP eligibility to the federal minimum.21 Combined with repeal of the coverage expansions and individual mandate, the number of uninsured children could rise by up to 16.5 million, with one in five uninsured, depending on what other coverage options might be available under a replacement plan.22

Repeal of the ACA insurance market reforms could weaken coverage for children in private plans. The ACA increased protections and enhanced coverage for children in private plans through insurance market reforms that apply to both the individual market and certain employer-sponsored plans. These reforms establish an essential health benefits package that includes dental and vision services for children and coverage of rehabilitative and habilitative services, which are particularly important for children with special health care needs. The reforms also provide for coverage of well-child visits, preventive screenings, and child immunizations with no cost sharing; prohibit lifetime limits on coverage and pre-existing condition exclusions; and cap out-of-pocket costs. Moreover, within the individual market, the ACA prohibits plans from denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on health status. If these reforms were repealed, children could face lifetime or annual caps on coverage, be subject to pre-existing condition exclusions, receive more narrow benefit packages, and be subject to cost sharing for preventive services and immunizations.

Restructuring of Medicaid

The Trump Administration and Republican leaders in Congress have called for fundamental changes that could limit federal Medicaid financing through a block grant or per capita cap. Unlike current law where eligible individuals have an entitlement to coverage and states are guaranteed federal matching dollars with no-preset limit, the proposals under consideration could eliminate both the entitlement and guaranteed match to achieve budget savings and to make federal funding more predictable. To achieve budget savings, federal funding caps would be set at levels below expected levels if current law were to stay in place. In exchange for a federal cap, proposals could allow states to eliminate the entitlement to coverage and impose enrollment caps or waiting lists, reduce eligibility levels, or offer states other increased flexibility to design and administer their programs. The effects of these proposals will depend on many factors including what happens to the ACA, the size of federal savings targets, how the base year for the block grant or cap would be established, and what flexibility would be provided to states.

Changes to Medicaid could have significant effects on large numbers of low-income children with significant health needs. In fiscal year 2015, 36.8 million children were covered by Medicaid (Appendix Table 2).23 Since the size and scope of Medicaid is much broader than CHIP, changes to Medicaid would have larger implications for children’s coverage. Changes to Medicaid would affect children with the lowest incomes and highest health care needs.

Capping federal financing for Medicaid through a block grant or per capita cap would shift risks and costs to states, enrollees, and providers and could result in reductions in coverage for children. Moving to a capped financing structure could lock historic spending patterns and variation in Medicaid programs in place and make the program less responsive to changes in economic conditions, public health needs, and changes in health care costs. Moreover, to respond to reductions in federal funding under a capped structure, states would need to increase state spending to maintain current programs or would need to identify ways to reduce program costs. Analysis suggests that even with increased program flexibility, states would need to reduce enrollment, benefits, or provider reimbursement levels if faced with large reductions in federal spending.24 Such changes could affect eligibility for children; the scope of coverage provided to children, including the EPSDT benefit; as well as the affordability of coverage and care.

Looking Ahead

The upcoming debates around CHIP, the ACA, and Medicaid are interrelated since outcomes in one area may affect another area. As proposals emerge, there is much at stake for children’s coverage:

Potential coverage losses for children. The uninsured rate for children has reached an all-time low of 5%, reflecting continued coverage gains over the last twenty years as a result of coverage expansions, streamlining of enrollment and renewal processes, and focused outreach and enrollment efforts. Loss of CHIP funding, repeal of the ACA, and broad restructuring of Medicaid all have the potential to move backward on these gains and significantly increase the number of uninsured children. Moreover, rollbacks of the ACA Medicaid and Marketplace coverage expansions for parents could negatively affect coverage of children, given that children are more likely to have coverage when their parent is insured.

More limited benefits and higher out-of-pocket costs for children’s coverage. Medicaid and CHIP have benefit packages designed to meet the needs of children, which provide more comprehensive benefits and cost protections compared to private plans. Medicaid’s EPSDT benefit provides children access to all medically necessary care, which facilitates pediatricians’ ability to make treatment decisions and supports children’s ability to access needed care. Changes that would move children from Medicaid or CHIP to private plans could result in them having more limited benefits and higher out-of-pocket costs. Moreover, if states are provided increased flexibility around benefits and premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid, children enrolled in Medicaid could receive more limited benefits and face higher costs. Such changes would have the most significant consequences for children with the highest medical needs, particularly if the changes affect the EPSDT benefit. Lastly, the ACA insurance market reforms enhanced benefits and cost protections for children enrolled in private plans. Repeal of those reforms could weaken coverage for children covered through private plans, potentially exposing them to narrower benefits, limits on coverage, and higher costs.

Reduced access to care for children and other long-term effects. Increases in the number of uninsured children and/or narrower benefit packages with higher cost sharing would result in fewer children accessing needed care, including preventive services such as well child visits and immunizations. Research further suggests that reductions in children’s coverage could also have broader long-term negative effects on their health, education, and financial success as adults. Coverage losses or reductions would also lead to increased stress and worry among parents and increased financial pressure on families.

Increased financial pressure on states and providers. The federal matching funds provided through Medicaid and CHIP are central to supporting state capacity to cover low-income children. Loss of CHIP funding would create funding gaps for states. Reductions in federal Medicaid financing could lead to even larger funding gaps given that it is much larger than CHIP. If there are significant reductions in federal funds, states would need to contribute more state funds to maintain existing coverage or make program reductions, which might include reductions in eligibility, benefits, or provider reimbursement levels. Moreover, any coverage losses among children could increase state costs in other areas of state budgets such as programs for uninsured individuals, behavioral health initiatives, and result in increases in uncompensated care costs.