2012 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health

Published:

Executive Summary

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2012 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health is the fourth in a series of surveys designed, conducted, and analyzed by the Kaiser Family Foundation in order to shed light on the American public’s perceptions, knowledge, and attitudes about the role of the United States in efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. The Foundation’s first major survey on this topic was conducted in early 2009, and updates were released in the fall of 2009 and in 2010. This latest survey updates trends from Kaiser’s previous work, and explores in greater detail what the public thinks about the U.S. role in the world, perceptions of spending on foreign aid in general and global health in particular, and the extent to which information may change opinions. We also explore new questions in this survey about how the public views U.S. support for global health compared with that of other donor nations, and perceptions about the potential effects of decreased U.S. funding.

Overall, our survey finds a majority of the American public believes the U.S. has a major role to play in the world, though many remain confused about the size and composition of U.S. foreign assistance. We also find that providing people with accurate information has the potential to move opinion significantly. For example, when survey respondents are told that only about one percent of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid (far less than what most believe when asked to estimate an amount) opinion moves from a majority saying the current level of spending is too high to the public being most likely to say spending is currently too low. And as we’ve seen in the past, people are also more supportive of foreign aid spending when a specific purpose is mentioned—in this case, improving the health of people in developing countries—than they are of the idea of foreign aid in general. Our analysis also shows that even when controlling for other factors, those who possess more accurate knowledge about how much the U.S. spends on foreign aid are more likely to support an increase in U.S. spending on health in developing countries.

Improving health in developing countries is one of many priorities the public sees as important for the president and Congress to address in world affairs, though security concerns, such as limiting the spread of nuclear weapons and fighting terrorism, rise somewhat above other priorities. Within health, basic needs such as providing clean water and reducing hunger, along with improving children’s health, are seen as the top priorities, though every health issue asked about in the survey is seen as important by a large majority of the public.

As has been the case since we began tracking opinion on global health several years ago, most Americans feel that the current level of U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries is either too low or about right. When it comes to the level of U.S. spending, global health appears to be one area where there is more bipartisan consensus than others. For example, while modest partisan differences exist on some aspects of U.S. global health involvement, these differences are much smaller than we find on questions of domestic health care policy and spending. Although Democrats are more likely than Republicans to place a top priority on certain issues within global health, majorities across parties feel that the current level of U.S. spending on health in developing countries is either too low or about right. The lack of deeper partisan divisions may be related to the fact that Americans seem to view global health as a moral issue; while most recognize various potential benefits to the U.S., the top reason people give for the U.S. to engage in efforts to improve health in developing countries is because “it’s the right thing to do.”

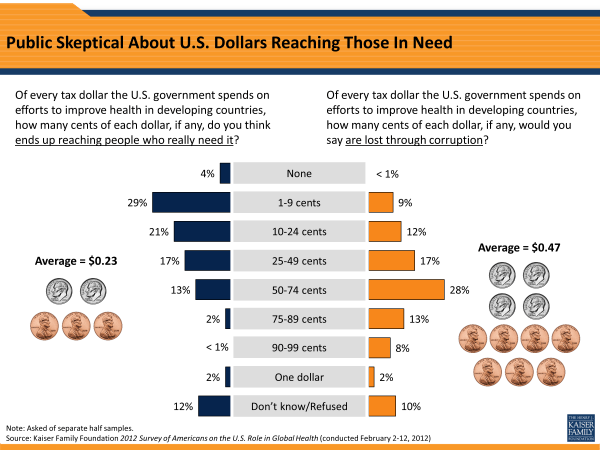

However, the public’s support for spending comes with some important caveats. Economic conditions at home make people hesitant to increase spending abroad, with two-thirds saying that given the serious economic problems facing the country and the world right now, the U.S. cannot afford to increase spending on health in developing countries. The public also remains divided on whether more spending will make a meaningful difference in improving health, and is deeply skeptical about how much U.S. money actually reaches people on the ground. Currently, the average American believes that less than a quarter of every U.S. dollar spent on health in developing countries actually reaches those who need it, and that nearly 50 cents of each dollar is lost through corruption.

Most Americans feel that the U.S. is already doing its fair share or more compared to other donor countries, and perhaps related to this, the public prefers multilateral approaches to aid and strongly supports giving through international organizations like the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the United Nations, and the World Health Organization. Still, most recognize the important role the U.S. plays, and majorities feel that if the president and Congress were to decrease spending on foreign assistance, there would be an increase in illness and death in developing countries, and that other wealthier countries would not step in to fill the gap. More broadly, the public sees lack of money and resources as a bigger barrier to improving health compared with lack of knowledge about how to treat health conditions in developing countries.

An ongoing challenge for those looking to increase the public’s level of interest in and support for U.S. global health efforts is grabbing the public’s attention in a competitive news environment. Since 2010, the share of the public saying they have heard any information about U.S. involvement in global health issues, as well as reported attention to health in developing countries generally, have both declined. In an election year and one in which the news continues to be dominated by domestic economic problems, garnering public attention for international health issues is likely to continue to be a struggle. One bright spot is that the public expresses at least some appetite for more coverage of these issues, with just over half saying the news media spends too little time covering health in developing countries, up from four in ten in 2010.

Report

Section 1: Foreign Aid and the U.S. Role in the World

Most See A Strong Role For The U.S. In The World, But Confusion About Foreign Aid Spending Persists

A solid majority of the public (60 percent) want the U.S. to play at least a “major” role in world affairs, but just 17 percent want the U.S. to play the “leading” role. Fewer than four in ten would prefer to see our country play only a minor role (26 percent) or no role at all (11 percent) in solving international problems.

| Figure 1: What Role Should the U.S. Play in Trying to Solve International Problems? | |

| Percent who say the U.S. should take… | |

| The leading role in world affairs | 17% |

| A major role, but not the leading role | 43 |

| A minor role | 26 |

| No role at all in world affairs | 11 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 3 |

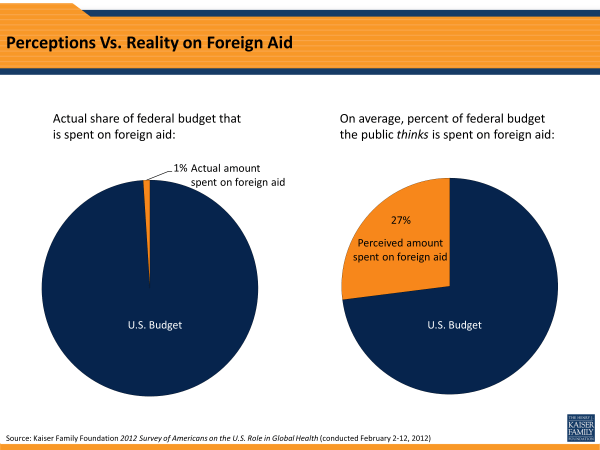

Previous Kaiser surveys have documented the public’s level of misunderstanding when it comes to the amount the U.S. spends on foreign aid. The 2012 survey again finds that the vast majority of the public overestimates the size of the federal budget that is spent on foreign aid, with just five percent correctly saying that foreign aid makes up one percent or less of the federal budget.1 A majority (57 percent) give answers above 10 percent, including 28 percent who think that foreign aid makes up more than 30 percent of the federal budget. On average, Americans answer that 27 percent of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid. In reality, this is closer to the amount spent on Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, combined with the interest on the national debt.2

| Figure 2: Just Your Best Guess, What Percentage of the Federal Budget is Spent on Foreign Aid? | |

| 0-1% of the federal budget | 5% |

| 2-5% | 11 |

| 6-10% | 13 |

| 11-20% | 17 |

| 21-30% | 12 |

| 31-40% | 10 |

| 41-50% | 7 |

| 51% or more | 11 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 13 |

Providing Accurate Information About Foreign Aid Spending Has The Potential To Change Views

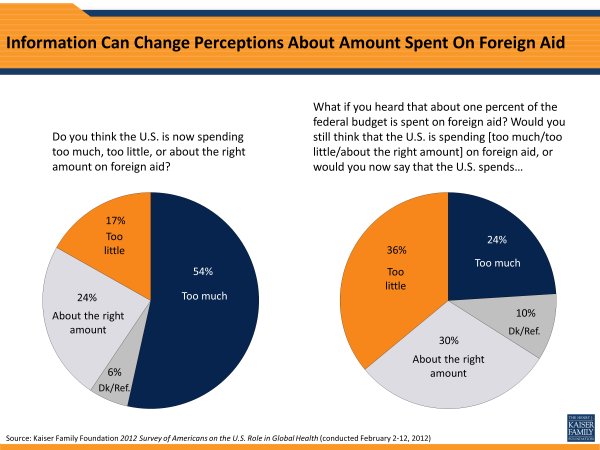

At the same time as they overestimate the amount of foreign aid spending, a majority of the public (54 percent) thinks the U.S. is now spending too much on foreign aid, and just 17 percent say we are spending too little, a finding that is consistent with previous Kaiser surveys. However, in this survey we took the additional step of giving respondents accurate information by telling them that about one percent of the federal budget is spent on foreign aid, and we found that this information has the potential to shift opinion dramatically. After hearing this information, the share saying the U.S. spends too little on foreign aid more than doubles, from 17 percent to 36 percent, while the share saying we spend too much drops in half, from 54 percent to 24 percent. Another three in ten think that one percent is about the right amount for the U.S. to be spending on foreign aid.3

Framing Matters In Public Perception Of Aid Spending, With More Support for Spending On “Improving Health” Versus “Foreign Aid”

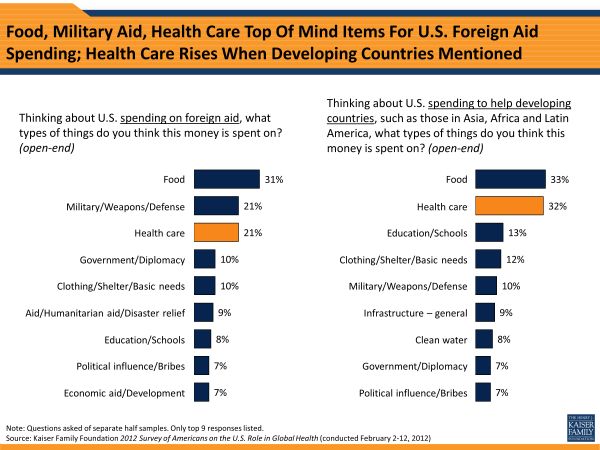

Perceptions—and misperceptions—about the amount of foreign aid spending may also be related to the public’s beliefs about what this money is spent on. When asked to name in their own words the types of things U.S. foreign aid pays for, military support is near the top of the list, tied with health care at 21 percent, and just behind food (31 percent). Other common responses include diplomacy, basic needs such as clothing and shelter, disaster relief, and education. When the question is framed around U.S. spending “to help developing countries” rather than “foreign aid,” food remains at the top, but responses related to health care and education move further up the list, while fewer people mention military aid (10 percent).

There is some evidence that these top-of-mind perceptions of how aid is spent are tied to people’s level of support for foreign aid spending. For example, those who think the U.S. spends too much on foreign aid are less likely to mention things like food and health care, and more likely to mention diplomacy and bribes/using money to gain political influence.

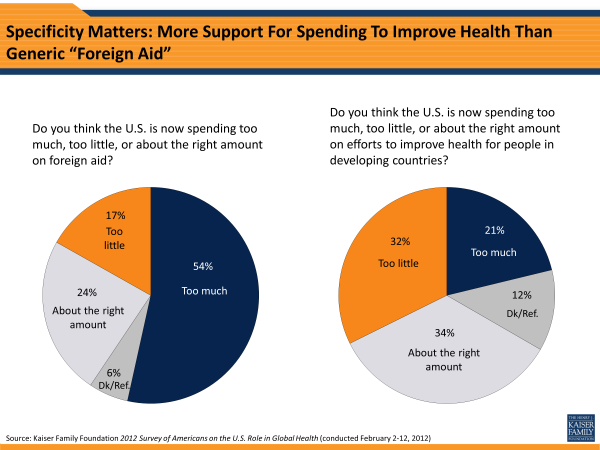

Framing also matters when it comes to how the spending question is asked. Kaiser surveys have consistently found that Americans are more likely to support U.S. spending for global health specifically than they are when asked about foreign aid in general. While most don’t possess accurate knowledge about the actual amount of U.S. spending, when asked their own perceptions, a majority of the public says the U.S. is now spending too little (32 percent) or about the right amount (34 percent) on efforts to improve health for people in developing countries, while about one in five (21 percent) say we are spending too much.

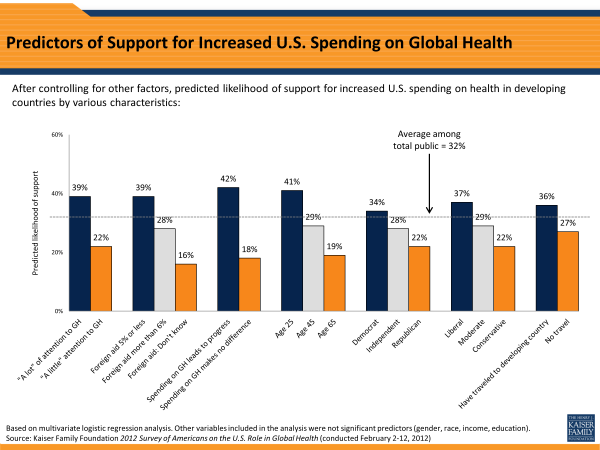

Who Is Most Likely To Support Increasing The Current Amount Of U.S. Spending On Global Health?

To address the question of which groups are most likely to support increased U.S. spending on improving health in developing countries, we analyzed which factors are associated with saying the U.S. currently spends “too little” on efforts to improve health in developing countries (32 percent of the public overall). We used multivariate logistic regression to look at the impact of demographic factors (gender, age, race/ethnicity, income, education, party identification, and ideology), as well as knowledge about foreign aid spending as a share of the federal budget, level of attention paid to global health issues, experience traveling to a developing country, and the belief that more spending will lead to meaningful progress.

After controlling for all these factors, we found that higher levels of attention to global health issues, more accurate knowledge about the share of the federal budget spent on foreign aid, and believing that more spending will lead to meaningful progress in improving health are all positively associated with support for increased U.S. spending on health in developing countries. To illustrate these differences, the chart below compares the predicted likelihood of support for increased spending for different groups, when all other factors are held constant. So, for example, the “average” person who pays a lot of attention to global health issues is almost twice as likely as the average person who pays just a little attention to support increased spending on global health (39 percent vs. 22 percent). Similarly, the average person who believes that more spending from the U.S. and other donor countries will lead to meaningful progress is more than twice as likely as the average person who thinks more spending won’t make a difference to support increased spending on global health (42 percent vs. 18 percent). And there is a similar difference between those with a more accurate perception of foreign aid spending and those with a less accurate perception. We also found several demographic factors to be positively associated with support for increased spending on global health, including younger age, identifying as a liberal or Democrat, and experience traveling to a developing country in the past five years.

This analysis reinforces another finding from this survey—that correcting misconceptions about foreign aid spending has the potential to change opinions. It also suggests that increasing the visibility of global health issues among the public, and convincing people of the effectiveness of such spending could be potentially successful strategies for those looking to gain broader support for U.S. global health efforts.

Section 2: Views on Global Health - Priorities and Problems

Health Among A List Of Priorities The Public Sees For U.S. In World Affairs

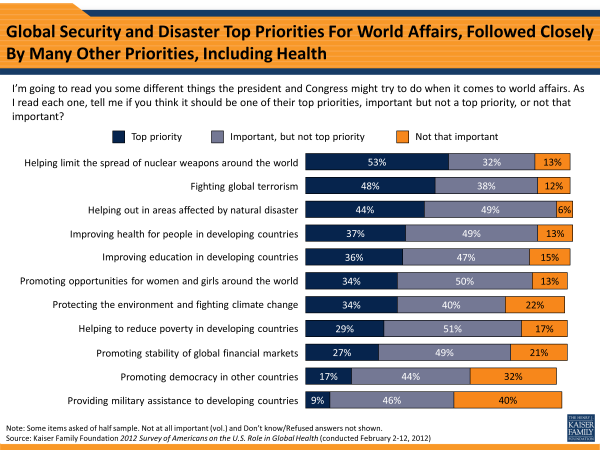

When it comes to different ways in which the U.S. might engage in world affairs, issues of safety and security, such as limiting the spread of nuclear weapons (53 percent) and fighting global terrorism (48 percent), top the public’s priority list, closely followed by disaster relief (44 percent). Following this is a cluster of issues seen as top priorities by more than a third of the public, including improving health in developing countries (37 percent), improving education (36 percent), promoting opportunities for women and girls (34 percent), and fighting climate change (34 percent). Almost three in ten place a top priority on reducing poverty in developing countries (29 percent) and promoting global financial stability (27 percent), while fewer prioritize promoting democracy (17 percent) and providing military assistance to developing countries (9 percent).

Within Health, All Priorities Seen As Important; Clean Water, Children’s Health, Hunger Rise To Top

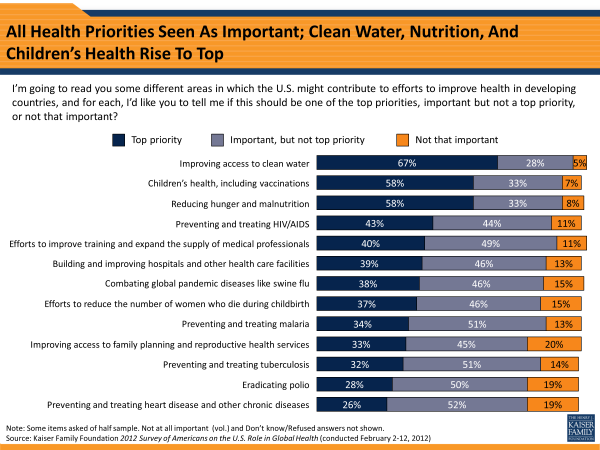

When asked about a variety of different priorities for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries, large majorities believe each area is important, and between a quarter and two-thirds say each should be “one of the top” priorities.

Highest on the list of those considered top priorities are popular causes such as improving access to clean water (67 percent), reducing hunger and malnutrition (58 percent), and children’s health, including vaccinations (58 percent). Several other areas are seen as top priorities by about four in ten Americans, including preventing and treating HIV/AIDS (43 percent), improving training and expanding the supply of medical professionals (40 percent), building and improving health care facilities (39 percent), combating global pandemic diseases like swine flu (38 percent), and reducing maternal deaths (37 percent). Somewhat lower on the list of top priorities (though still considered important by sizable majorities) are preventing and treating malaria (34 percent), improving access to family planning and other reproductive health services (33 percent), preventing and treating tuberculosis (32 percent), eradicating polio (28 percent), and preventing and treating chronic diseases (26 percent).

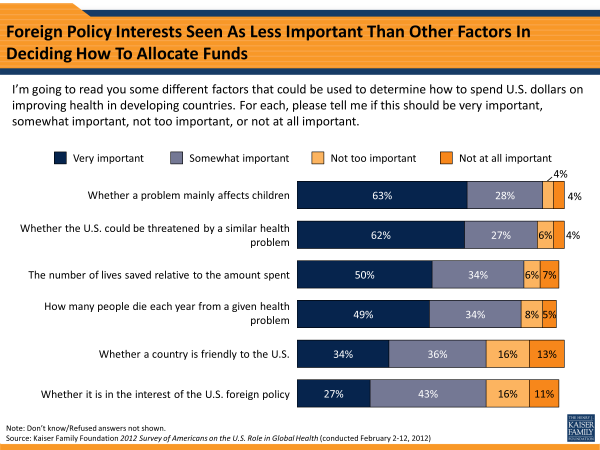

In terms of which criteria should be used to determine allocation of U.S. spending on health in developing countries, the public ranks two factors at the top of the list: whether a problem mainly affects children, and whether the U.S. could be threatened by a similar health problem (six in ten say each of these should be “very important” in determining how U.S. dollars are spent). Roughly half also say “the number of lives saved relative to the amount spent” and (50 percent) “how many people die each year from a given health problem” (49 percent) should be very important criteria. U.S. foreign policy concerns rank lower on the list, with about a third (34 percent) placing great importance on whether a country is friendly to the U.S., and just over a quarter (27 percent) saying the same about whether it is in the interest of U.S. foreign policy.

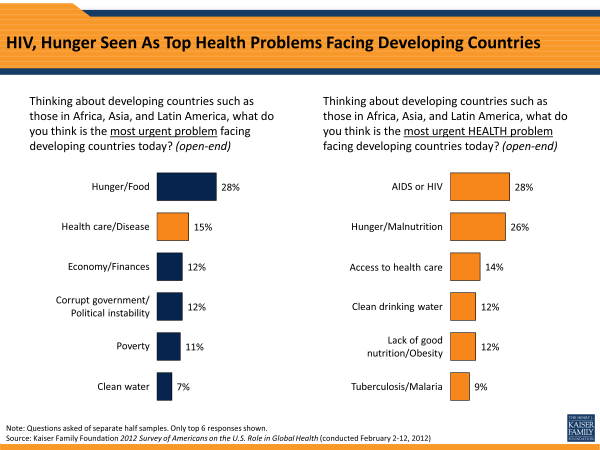

Hunger and Health Seen As Biggest Problems Facing Developing Countries Generally; Within Health, Hunger And HIV Seen As Top Problems

When it comes to the problems Americans perceive to be facing developing countries, hunger and lack of food top the list in an open-ended question (28 percent), followed by health and disease (15 percent), economic problems (12 percent), government corruption (12 percent), and poverty (11 percent). Hunger is also top-of-mind for many people when it comes to health specifically. When asked to name the most urgent health problems facing developing countries, HIV/AIDS (28 percent) and hunger/malnutrition (26 percent) are at the top of the list, followed by access to health care (14 percent), clean drinking water (12 percent), and obesity/lack of good nutrition (12 percent).

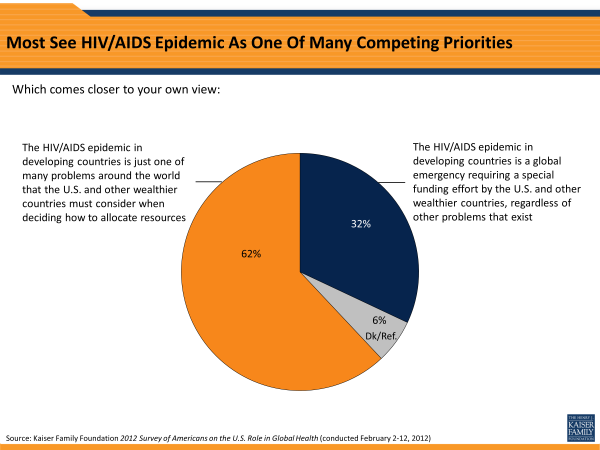

While HIV/AIDS continues to be at the top of the list of health problems perceived as most urgent for developing countries, the share mentioning HIV fell from 44 percent in 2010 to 28 percent in 2012. When asked more specifically how they view the HIV/AIDS epidemic in developing countries and the U.S. response, six in ten Americans (62 percent) say HIV/AIDS is “just one of many problems around the world that the U.S. and other wealthier countries must consider when deciding how to allocate resources,” while about half as many—32 percent—view it as “a global emergency requiring a special funding effort by the U.S. and other wealthier countries, regardless of other problems that exist.”

Section 3: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending

Despite General Support For Current Level Of U.S. Spending On Global Health, Skepticism About Progress And Concerns About Economy Make Americans Wary Of Increasing Spending

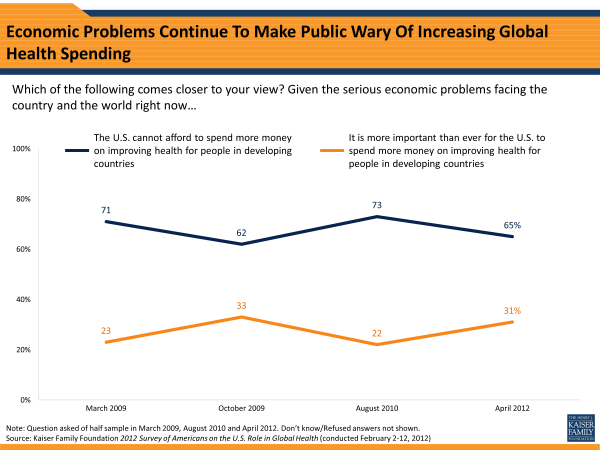

While two-thirds of Americans say that the current level of U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries is too little or about right, economic concerns continue to make the public wary of the idea of increasing spending abroad. In 2012, nearly two-thirds (65 percent) say that given the serious economic problems facing the country and the world, the U.S. cannot afford to spend more money on health in developing countries, while three in ten feel the current economic conditions make it more important than ever for the U.S. to increase such spending.

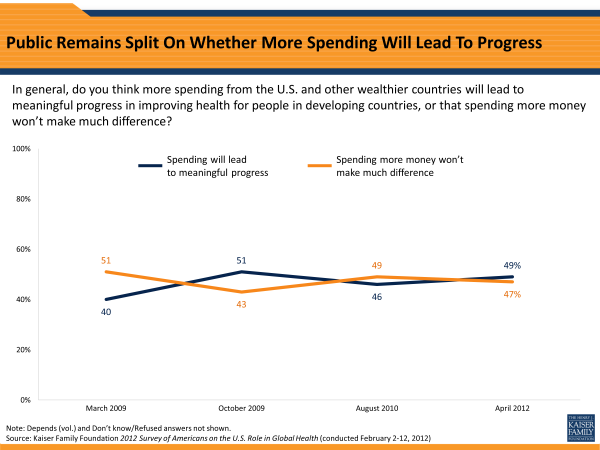

As previous Kaiser surveys have also shown, the public’s reluctance to increase U.S. spending on global health efforts may be related to the fact that Americans are divided as to whether more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health in developing countries (49 percent) or won’t make much difference (47 percent).

This skepticism about the ability of additional spending to lead to progress ties in with another key finding from the survey: many Americans do not believe that U.S. money is getting to where it needs to be on the ground, and most perceive that a large share of this money is being lost through corruption. On average, Americans believe just 23 cents of every tax dollar the U.S. spends on improving health in developing countries ends up reaching people who really need it. The public believes twice as much money—47 cents of every tax dollar spent on these efforts—is lost through corruption.

Trends In Attitudes Toward U.S. Spending On Health In Developing Countries

On several measures of attitudes toward U.S. spending on health in developing countries, Americans’ views appear to have gotten somewhat more generous since the summer of 2010. For example, 32 percent now say the U.S. spends too little in this area, up 9 percentage points since 2010, and 31 percent now say the economic crisis makes it more important than ever for the U.S. to spend more on health in developing countries, also up 9 percentage points. These marks do not represent new high points in support for increased spending, however, but rather a return to the levels seen in the fall of 2009.

| Figure 16: Trends in Views on U.S. Global Health Spending | |||||

| Mar 2009 | Oct 2009 | 2010 | 2012 | ||

| Amount U.S. spends to improve health in developing countries is… | |||||

| …too much | 23% | 25% | 28% | 21% | |

| …about right | 39 | 32 | 42 | 34 | |

| …too little | 26 | 34 | 23 | 32 | |

| U.S. should spend its tax dollars on improving health… | |||||

| …in the U.S. only | n/a | n/a | 48 | 42 | |

| …in the U.S. and globally | n/a | n/a | 49 | 55 | |

| Given the serious economic conditions facing the country and world… | |||||

| …U.S. cannot afford to spend more on health in developing countries | 71 | 62 | 73 | 65 | |

| …it is more important than ever for the U.S. to spend more | 23 | 33 | 22 | 31 | |

Democrats More Likely Than Republicans To Place Top Priority On Health Issues; Still, Majorities Across Parties Think Current Level Of U.S. Global Health Spending Is Too Low Or About Right

While many questions of U.S. policy, particularly those that involve spending, tend to be polarizing and characterized by large differences by political party, partisan differences in opinion on U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries appear to be more modest. For example, while those who identify as Republicans are somewhat more likely to favor a decrease in current levels of spending and Democrats are more likely to favor an increase, a healthy majority of Democrats (74 percent), independents (66 percent), and Republicans (59 percent) perceive current levels of spending to be too little or about right.

Framing the question in terms of U.S. tax dollars produces somewhat more of a division, with a majority of Democrats (60 percent) and independents (57 percent) saying tax dollars should be spent on improving health in the U.S. and globally, while Republicans are more split between spending tax dollars on improving health in the U.S. only (48 percent) or at home and abroad (47 percent). Still, these partisan differences are much smaller than the differences that surveys tend to measure on many other policy issues, such as recent debates about the domestic health reform law.

Some underlying partisan differences in perceptions of the impact of U.S. spending on health in developing countries may help explain the small but measurable differences in support for spending. For example, while a majority (57 percent) of Democrats believe that more spending from the U.S. and other wealthier countries will lead to meaningful progress in improving health, a similar share of Republicans (58 percent) feel that more spending won’t make much difference. And across the board, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to feel that spending money on health in developing countries brings benefits to the U.S., including protecting the health of Americans, improving the U.S. image in the world, helping U.S. national security, and helping the U.S. economy by creating new markets for U.S. goods.

When asked about various priorities for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries, majorities across all parties say each of the 13 priorities asked about in the survey is important. However, there are certain areas that Democrats are more likely than Republicans to rank as “top priorities.” The biggest partisan differences are in the share placing a top priority on reducing hunger and malnutrition (76 percent of Democrats vs. 39 percent of Republicans), improving access to family planning and reproductive health services (40 percent vs. 16 percent), preventing and treating heart disease and other chronic diseases (35 percent vs. 12 percent), and improving access to clean water (76 percent vs. 58 percent).

| Figure 17: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending by Political Party ID | |||||

| Total | Dems | Inds | Reps | D-R | |

| Amount U.S. spends to improve health in developing countries is… | |||||

| …too much | 21% | 15% | 22% | 28% | -13 |

| …about right | 34 | 34 | 32 | 40 | -6 |

| …too little | 32 | 40 | 34 | 19 | +21 |

| TOTAL TOO LITTLE OR ABOUT RIGHT | 66 | 74 | 66 | 59 | +15 |

| U.S. should spend its tax dollars on improving health… | |||||

| …in the U.S. only | 42 | 38 | 42 | 48 | -10 |

| …in the U.S. and globally | 55 | 60 | 57 | 47 | +13 |

| More spending from the U.S. and other countries… | |||||

| …will lead to meaningful progress in improving health | 49 | 57 | 50 | 37 | +20 |

| …won’t make much difference | 47 | 38 | 48 | 58 | -20 |

| Percent who say spending money on health in developing countries… | |||||

| Helps protect the health of Americans | 70 | 82 | 66 | 62 | +20 |

| Helps the U.S. economy | 42 | 50 | 42 | 35 | +15 |

| Helps U.S. national security | 45 | 51 | 43 | 39 | +12 |

| Helps improve the U.S. image in the world | 58 | 63 | 59 | 52 | +11 |

| Percent who say each of the following should be “one of the top priorities” for U.S. efforts to improve health in developing countries: | |||||

| Reducing hunger and malnutrition | 58 | 76 | 54 | 39 | +37 |

| Improving access to family planning and reproductive health services | 33 | 40 | 35 | 16 | +24 |

| Preventing and treating heart disease and other chronic diseases | 26 | 35 | 26 | 12 | +23 |

| Improving access to clean water | 67 | 76 | 65 | 58 | +18 |

| Efforts to improve training and expand the supply of medical professionals | 40 | 47 | 40 | 31 | +16 |

| Preventing and treating malaria | 34 | 39 | 34 | 23 | +16 |

| Eradicating polio | 28 | 34 | 26 | 18 | +16 |

| Children’s health, including vaccinations | 58 | 64 | 59 | 50 | +14 |

| Preventing and treating HIV/AIDS | 43 | 47 | 45 | 37 | +10 |

| Efforts to reduce the number of women who die during childbirth | 37 | 38 | 38 | 31 | +7 |

| Building and improving hospitals and other health care facilities | 39 | 40 | 39 | 34 | +6 |

| Combating global pandemic diseases like swine flu | 38 | 44 | 36 | 39 | +5 |

| Preventing and treating tuberculosis | 32 | 31 | 31 | 30 | +1 |

Most Think A Decrease In U.S. Funding Would Result In More Illness And Death, And Few Think Others Would Step In To Fill Gap

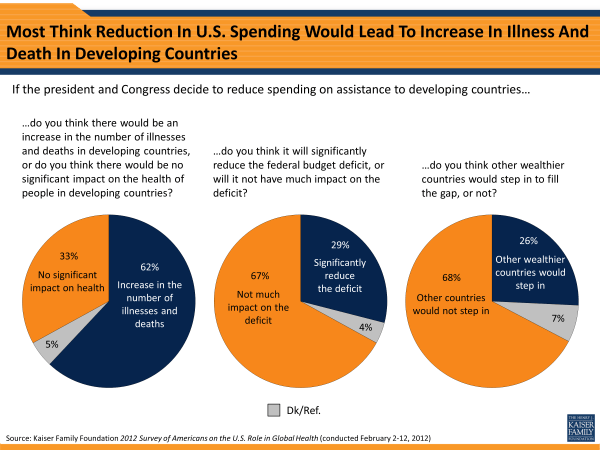

At the same time that they are skeptical about more spending leading to progress, a majority of the public (62 percent) agrees that if the president and Congress decide to reduce spending on assistance to developing countries, there would be an increase in the number of illnesses and deaths, while a third (33 percent) think such a decrease would not have a significant impact on the health of people in these countries. Further, two-thirds (67 percent) feel that a decrease in spending on assistance to developing countries would not have much impact on the federal budget deficit, while three in ten (29 percent) believe the deficit would be significantly reduced.

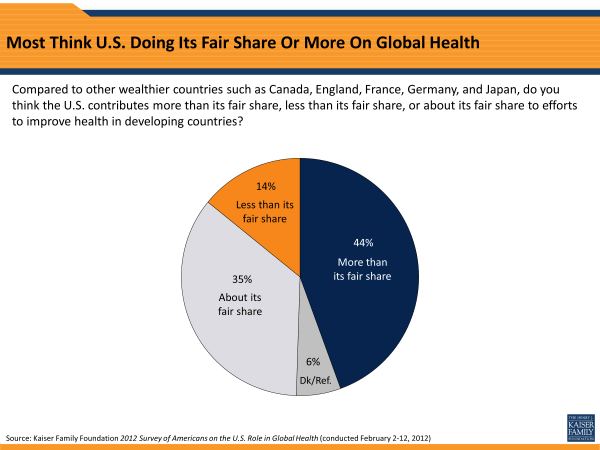

Only about a quarter (26 percent) of the public believes that if the U.S. were to decrease spending on assistance to developing countries, other wealthier countries would step in to fill the gap. In fact, the largest share of Americans—44 percent—believe that compared to other wealthier countries, the U.S. already contributes more than its fair share to efforts to improve health in developing countries. Another third (35 percent) believe the U.S. share is about right, while just 14 percent feel the U.S. currently contributes less than its fair share. 1

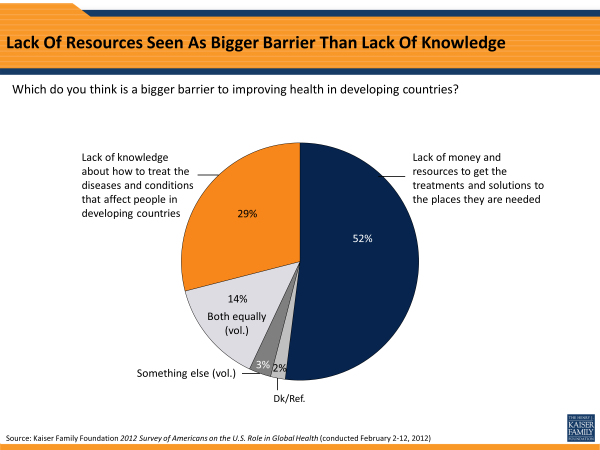

More generally, Americans seem to recognize that lack of resources is a major roadblock to making progress on health. When asked which is the bigger barrier to improving health in developing countries, more than half (52 percent) choose lack of money and resources, while three in ten (29 percent) choose lack of knowledge about how to treat the diseases and conditions affecting people in these countries.

Section 4: Approaches to Aid and Reasons for U.S. to Spend

Americans Continue To Favor Multilateral Approaches And Support For International Organizations

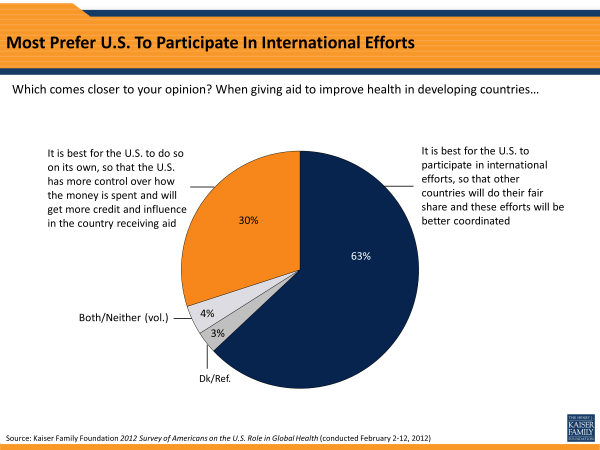

Perhaps related to the sense that the U.S. is already bearing more than its fair share of the burden, Americans continue to prefer multilateral approaches to global health aid. More than six in ten (63 percent) say that when giving aid to improve health in developing countries, “it is best for the U.S. to participate in international efforts, so that other countries will do their fair share and these efforts will be better coordinated,” while half as many (30 percent) say it is best for the U.S. “to do so on its own, so that the U.S. has more control over how money is spent and will get more credit and influence in the country receiving aid.”

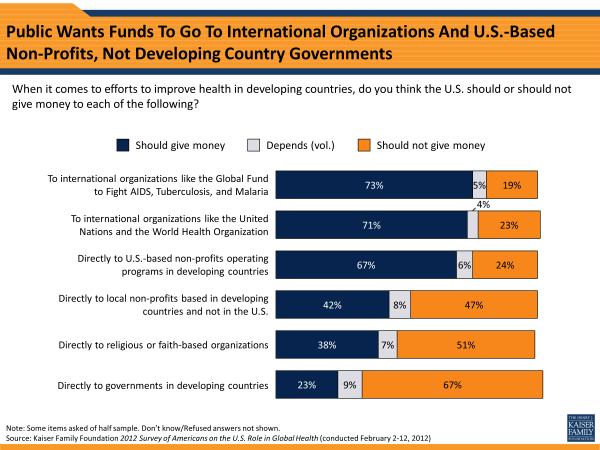

In another show of support for coordinated, multilateral efforts, large shares say that the U.S. should give money to international organizations. Support is high regardless of whether the specific organizations mentioned in the question are the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (73 percent say we should give money) or the United Nations and the World Health Organization (71 percent). Two-thirds (67 percent) also think the U.S. should give directly to U.S.-based non-profits operating programs in developing countries. The public is somewhat more divided on whether the U.S. should give money directly to local non-profits that are based in developing countries and not in the U.S. (42 percent say we should, 47 percent say we shouldn’t). And about half (51 percent) would prefer the U.S. not give directly to religious or faith-based organizations, while just over a third (38 percent) say we should. Perhaps not surprisingly, Evangelical Christians (50 percent) and those who place a strong personal importance on religion (53 percent) are more likely than others to favor giving to faith-based organizations. The public comes down clearly against giving money directly to governments in developing countries, with 67 percent saying we should not.

While majorities across political party affiliation support multilateral approaches to aid, there are some measurable partisan differences in attitudes in this area. Though it is a minority view across all parties, a larger share of Republicans (37 percent) compared with Democrats (24 percent) say it is better for the U.S. to give aid on its own, in order to retain control over how money is spent and receive more credit in the countries receiving aid. Republicans (55 percent) are also more likely than Democrats (38 percent) to feel that the U.S. is already contributing more than its fair share to global health efforts compared to other donor countries. And while still a majority, smaller shares of Republicans than Democrats say that when giving money to improve health in developing countries, the U.S. should give money to international organizations like the United Nations, the World Health Organization, and the Global Fund.

| Figure 23: Views on Multilateral Approaches by Political Party | |||||

| Total | Dems | Inds | Reps | D-R | |

| When giving aid to improve health in developing countries, it is best for the U.S. to… | |||||

| …participate in international efforts | 63% | 70% | 64% | 54% | +16 |

| …do so on its own | 30 | 24 | 31 | 37 | -13 |

| Compared to other wealthier countries, the U.S. contributes… | |||||

| …more than its fair share | 44 | 38 | 44 | 55 | -17 |

| …about its fair share | 35 | 37 | 34 | 34 | +3 |

| …less than its fair share | 14 | 18 | 16 | 6 | +12 |

| U.S. should/should not give money to international organizations like UN and WHO… | |||||

| …should | 71 | 87 | 73 | 52 | +35 |

| …should not | 23 | 10 | 23 | 42 | -32 |

| U.S. should/should not give money to international organizations like the Global Fund… | |||||

| …should | 73 | 84 | 73 | 63 | +21 |

| …should not | 19 | 10 | 23 | 23 | -13 |

Americans See Benefits At Home, But Most Think U.S. Should Give Because It’s The Right Thing To Do

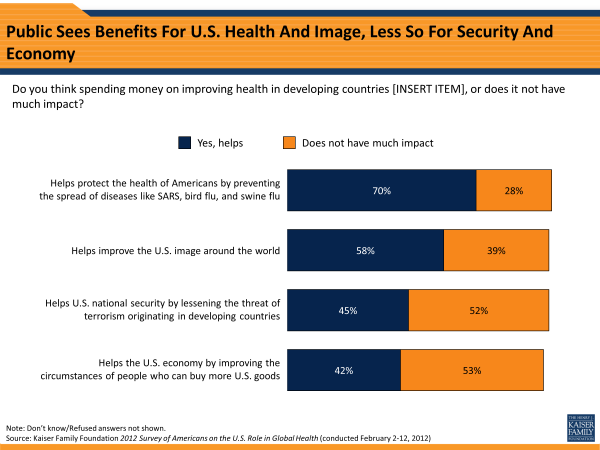

Americans see several clear benefits to the U.S. from engaging in global health efforts. Seven in ten believe that spending money on health in developing countries helps protect the health of Americans at home by preventing the spread of diseases like SARS, bird flu, and swine flu, and nearly six in ten (58 percent) say such spending helps improve the U.S. image around the world.

The public is somewhat less convinced that U.S. spending on health in developing countries helps U.S. national security by lessening the threat of terrorism originating in these countries (45 percent say it does, 52 percent say it does not), and that it helps the U.S. economy by creating new markets for U.S. goods (42 percent say it does, 53 percent say it does not).

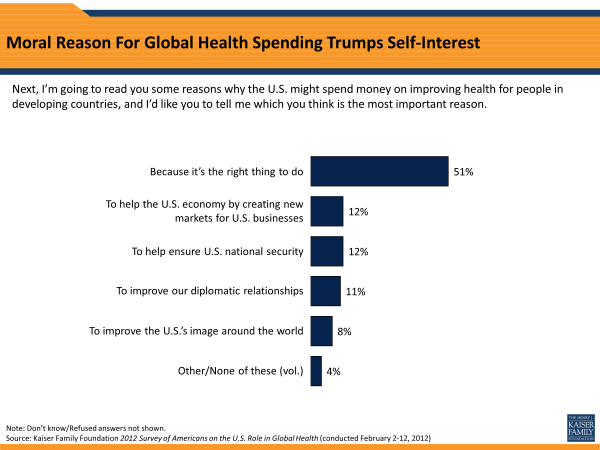

Despite recognizing some potential benefits to the U.S., the moral argument continues to trump such “self-interest” arguments when it comes to reasons for the U.S. to give. Half (51 percent) say the most important reason for the U.S. to spend money on health in developing countries is “because it’s the right thing to do,” while much smaller shares see the top reason as helping the U.S. economy (12 percent), ensuring U.S. national security (12 percent), improving diplomatic relationships (11 percent) or improving the U.S. image in the world (8 percent).

Section 5: Visibility and Attention to Global Health

Declining Awareness/Visibility Of Global Health Issues

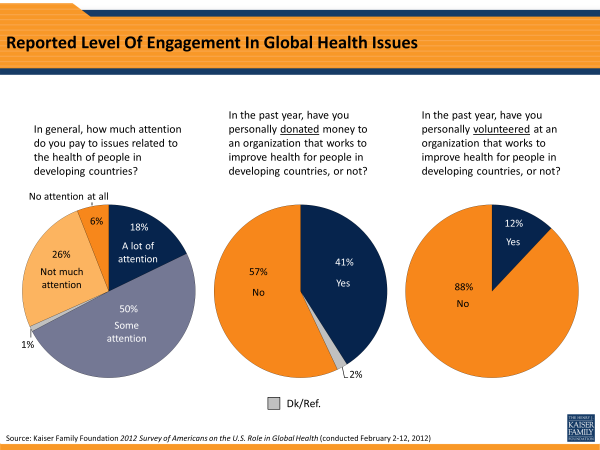

One challenge for those looking to increase the public’s level of support for U.S. spending on global health is that there are some indications that visibility of the issue may have declined somewhat since the summer of 2010. This decline may not be surprising given that 2012 is an election year, and one in which the news has continued to be dominated by the economic problems facing the country. While a majority of the public reports paying at least “some” attention to issues related to health in developing countries, fewer than one in five (18 percent) say they pay “a lot” of attention to these issues. The share saying they pay at least “some” attention is down somewhat, from 75 percent in August 2010 to 68 percent in 2012.

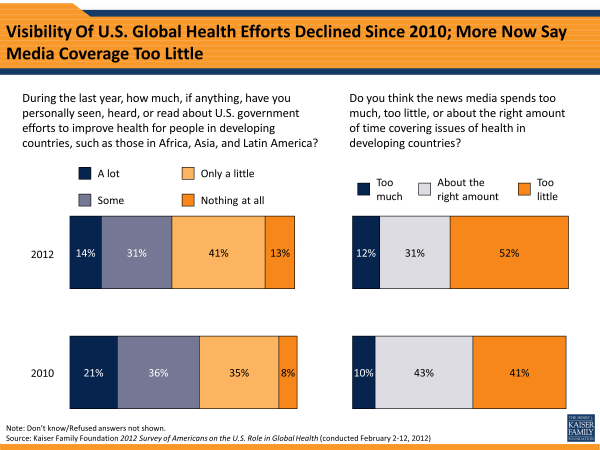

Similarly, there’s been a decline in the share saying they’ve heard more than a little in the past year about U.S. government efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. Currently, 45 percent say they’ve heard “a lot” (14 percent) or “some” (31 percent), down from a total of 57 percent who reported hearing “a lot” (21 percent) or “some” (36 percent) in 2010.

In light of this decline in visibility, the public has become somewhat more likely to say the news media is not devoting enough time to covering issues of health in developing countries. Currently, roughly half (52 percent) say the news media spends too little time on the topic, up from 41 percent in 2010. At the same time, the share who say the media spends about the right amount of time on the issue declined from 43 percent to 31 percent, while about one in ten continue to believe the media devotes too much time to the issue.

Age Differences In Support, Optimism, And Attention

While there is a lot of agreement across various demographic groups on questions of U.S. global health policy, some distinct age trends emerge in this survey. Compared with their older counterparts, younger adults are more likely to support increasing U.S. spending on health in developing countries, more optimistic that spending will lead to progress and will bring various benefits to the U.S., and less skeptical about the amount of U.S. global health spending lost through corruption.

For example, more than half of adults under age 30 (53 percent) think the U.S. currently spends too little on health in developing countries, compared with just 18 percent of those ages 65 and older. And while a majority of those ages 50 and older feel that the U.S. contributes more than its fair share compared to other donor nations, just about a quarter of 18-29 year-olds feel the same way. Perhaps reflecting the optimism of youth, a clear majority (62 percent) of adults under 30 believe that more spending from the U.S. and others will lead to meaningful progress in improving health in developing countries, while a similar majority of seniors (57 percent) think more spending won’t make much difference (those between the ages of 30-64 are more split). Younger Americans are also more likely than older ones to believe that spending to improve health in developing countries helps improve the U.S. image in the world, protects the health of Americans at home, and is helpful for the U.S. economy and national security. And seniors are more than twice as likely as those under 30 to believe that at least 75 cents of each U.S. dollar spent on health in developing countries is lost through corruption (34 percent vs. 15 percent).

At the same time, younger adults are less likely than older Americans to report paying close attention to the issue of health in developing countries, and less likely to report hearing news about U.S. global health efforts in the past year. Just a third (33 percent) of those ages 18-29 say they’ve heard “a lot” or “some” in the past year about U.S. government efforts to improve health in developing countries, compared with six in ten of those ages 65 and older.

| Figure 28: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending by Age | ||||

| 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-64 | 65+ | |

| U.S. spending to improve health in developing countries is… | ||||

| …too much | 12% | 22% | 23% | 29% |

| …about right | 27 | 35 | 38 | 36 |

| …too little | 53 | 30 | 29 | 18 |

| Compared to other wealthier countries, the U.S. contributes… | ||||

| …more than its fair share | 26 | 43 | 55 | 52 |

| …about its fair share | 42 | 37 | 31 | 32 |

| …less than its fair share | 23 | 14 | 10 | 9 |

| More spending from the U.S. and other countries… | ||||

| …will lead to meaningful progress in improving health | 62 | 51 | 46 | 34 |

| …won’t make much difference | 37 | 44 | 51 | 57 |

| Percent who say spending money on health in developing countries… | ||||

| Helps improve the U.S. image in the world | 72 | 64 | 52 | 44 |

| Helps protect the health of Americans | 73 | 81 | 72 | 65 |

| Helps the U.S. economy | 51 | 46 | 39 | 32 |

| Helps U.S. national security | 56 | 46 | 41 | 34 |

| Percent who say cents of U.S. tax dollars spent on health in developing countries that are lost through corruption is… | ||||

| …less than 25 cents | 33 | 28 | 10 | 13 |

| …25-74 cents | 41 | 43 | 55 | 40 |

| …75 cents or more | 15 | 19 | 29 | 34 |

| During the last year, how much seen, heard, or read about U.S. government efforts to improve health in developing countries… | ||||

| …a lot/some | 33 | 41 | 49 | 60 |

| …only a little/none | 66 | 58 | 50 | 39 |

| How much attention you usually pay to health in developing countries… | ||||

| …a lot/some | 61 | 65 | 70 | 77 |

| …not much/none | 39 | 35 | 30 | 21 |

Three In Ten Name A Leader On Global Health; Barack Obama, Bill Gates, Bill Clinton Top List

Perhaps surprisingly given this low level of visibility, three in ten Americans are able to name a person they think of as a leader in efforts to improve health for people in developing countries. At the top of the list are President Barack Obama (named by 5 percent) and entrepreneur and philanthropist Bill Gates (named by 5 percent, which includes mentions of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), followed by former President Bill Clinton (4 percent). Various other individuals were mentioned by about 1 percent of the public each, including former presidents Jimmy Carter and George Bush, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey, Bono, Angelina Jolie, Sean Penn, and George Clooney.

Section 6: Conclusion

Since the Kaiser Family Foundation began tracking public opinion on the U.S. role in global health in 2009, we have consistently found solid levels of support among the public for current levels of U.S. global health spending, along with the caveat that the current economic situation makes most Americans wary of increasing such spending. This survey illuminates several opportunities and challenges for those looking to increase the public’s level of support for U.S. global health efforts. While misperceptions about the size of U.S. foreign aid continue to be a challenge, an opportunity can be found in the fact that accurate information has the potential to “move the needle” in this area. By simply telling people that foreign aid makes up only one percent of the budget, opinion shifts from a majority saying the U.S. currently spends too much on foreign aid to two-thirds saying we spend either too little or about the right amount.

Another opportunity lies in the degree to which there is bipartisan agreement among the public about current levels of U.S. spending on health in developing countries. In contrast to many domestic policy issues which tend to be more divisive, those looking to rally support for U.S. global health efforts may find potential supporters among Democrats, Republicans, and independents alike. And those looking toward the future may be encouraged by the fact that young adults are among those most likely to support increased U.S. involvement. Our analysis also finds that those who pay a lot of attention to global health issues and those who believe more spending will lead to meaningful progress are more likely to support an increase in U.S. funding for global health, suggesting that increasing the visibility of these issues and convincing people of the effectiveness of spending could be potentially successful strategies in gaining broader public support.

On the challenge side, perhaps the biggest challenge lies in the public’s skepticism about the amount of U.S. money that actually reaches people on the ground in developing countries versus being lost through corruption. It may be hard to convince the public to support an increase U.S. funding for global health as long as they continue to perceive that less than a quarter of every U.S. tax dollar spent on health in developing countries actually reaches those in need. And finally, declining attention to and visibility of global health issues presents an ongoing challenge for those looking to raise awareness of these issues, and one that is likely to continue throughout 2012 as the media focuses on the state of the U.S. economy and, increasingly, on the presidential election campaign.

Methodology

The Kaiser Family Foundation 2012 Survey of Americans on the U.S. Role in Global Health was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation led by Mollyann Brodie, Ph.D., including Liz Hamel, Bianca DiJulio, Sarah Cho, and Theresa Boston, with input and guidance from Jennifer Kates, Ph.D., and Alicia Carbaugh. The survey was conducted February 2-12, 2012, among a nationally representative random digit dial telephone sample of 1,205 adults ages 18 and older, living in the United States, including Alaska and Hawaii (note: persons without a telephone could not be included in the random selection process). Computer-assisted telephone interviews conducted by landline (700) and cell phone (505, including 239 who had no landline telephone) were carried out in English and Spanish by Braun Research, Inc. under the direction of Princeton Survey Research Associates International (PSRAI). Both the landline and cell phone samples were provided by Survey Sampling International, LLC. For the landline sample, respondents were selected by asking for the youngest adult male or female currently at home based on a random rotation. If no one of that gender was available, interviewers asked to speak with the youngest adult of the opposite gender. For the cell phone sample, interviews were conducted with the person who answered the phone.

The combined landline and cell phone sample was weighted to balance the sample demographics to match estimates for the national population data from the Census Bureau’s 2011 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) on sex, age, education, race, Hispanic origin, and region along with data from the 2000 Census on population density. The sample was also weighted to match current patterns of telephone use using data from the January-June 2011 National Health Interview Survey. The weight takes into account the fact that respondents with both a landline and cell phone have a higher probability of selection in the combined sample and also adjusts for the household size for the landline sample. All statistical tests of significance account for the effect of weighting. Weighted and unweighted values for key demographic variables are shown in the table below.

| SAMPLE DEMOGRAPHICS | ||

| Unweighted | Weighted | |

| GENDER | ||

| Male | 53.1% | 49.3% |

| Female | 46.9% | 50.7% |

| AGE | ||

| 18-24 | 8.1% | 12.6% |

| 25-34 | 12.9% | 16.1% |

| 35-44 | 13.4% | 17.8% |

| 45-54 | 17.8% | 17.9% |

| 55-64 | 21.6% | 16.2% |

| 65+ | 23.5% | 16.7% |

| EDUCATION | ||

| Less than HS Grad. | 7.3% | 12.3% |

| HS Grad. | 28.6% | 33.7% |

| Some College | 24.8% | 24.4% |

| College Grad. | 38.1% | 28.5% |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | ||

| White/not Hispanic | 72.3% | 67.0% |

| Black/not Hispanic | 9.4% | 11.0% |

| Hispanic | 12.0% | 13.7% |

| Other/not Hispanic | 3.8% | 5.9% |

| PARTY IDENTIFICATION | ||

| Democrat | 31.5% | 32.0% |

| Independent | 34.9% | 35.3% |

| Republican | 23.6% | 22.1% |

| Other | 6.1% | 5.9% |

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. For results based on subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margin of sampling errors for other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll.

The response rate calculated based on the American Association for Public Opinion Research Response Rate 3 formula (AAPOR RR3) was 24 percent for the landline sample and 21 percent for the cell phone sample.

Endnotes

Report

Section 1: Foreign Aid and the U.S. Role in the World

Total spending by the U.S. on foreign aid represents approximately one percent of the federal budget. This spending is made up of economic assistance, including for health and other development projects, as well as international security assistance, which includes foreign military financing and training, peacekeeping, and other activities. See Department of State, FY 2013 Congressional Budget Justification for Foreign Operations, March/April 2012, http://www.state.gov/f/releases/iab/fy2013cbj/index.htm; and Department of State, State and USAID – FY 2013 Budget, February 2012, http://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2012/02/183808.htm

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Policy Basics: Where Do Our Federal Tax Dollars Go? http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=1258

Other Kaiser surveys have asked more specifically about reductions in spending on foreign aid and other areas as a way to reduce the federal budget deficit, and have found that much larger shares of the public would support major reductions in spending on foreign aid compared with other areas. See, for example, Kaiser Health Tracking Poll April 2011, http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/8180.cfm

Section 3: Views on U.S. Global Health Spending

In absolute dollar amounts, the U.S. government gave more than any other donor country in Official Development Assistance (ODA) for health from 2002-2009. When looking at health ODA as a share of each country’s GDP, the U.S. ranked eighth during this time period. For more information, see Kaiser Family Foundation Donor Funding for Health in Low- & Middle-Income Countries, 2002-2009, http://www.kff.org/globalhealth/7679.cfm.