Note: This analysis was updated on July 18, 2024, to use 2022 data for the overall estimate of women of reproductive age with Medicare and includes the addition of state-level estimates.

Key Takeaways

- Over one million women of reproductive age (20 to 49 years) receive their health insurance coverage from Medicare, qualifying for Medicare coverage because of having a long-term disability. Compared to women with Medicare who are ages 65 and over, women of reproductive age with Medicare are more likely to be Black or Hispanic, have lower incomes, be in worse health, and experience functional and cognitive impairment.

- Medicare coverage of many preventive sexual and reproductive health services, including wellness visits, screenings for sexually transmitted infections and HIV, and cancer screenings, is on par with coverage in Medicaid and private insurance.

- Many contraceptive products are covered under Medicare’s Part D prescription drug benefit, but coverage and cost sharing for specific contraceptive products vary across Medicare Part D plans. In general, Part D coverage of intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants is not widespread in 2024, though most Part D enrollees are in plans that cover contraceptive pills, rings, patches, and injections. While the out-of-pocket cost for some contraceptive products is relatively low, some Part D enrollees could pay up to a $100 copayment or 50% coinsurance for certain higher-cost contraceptive products.

- While Medicare covers many types of contraception, coverage is more limited than Medicaid and private insurance, which generally cover all U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved, -granted or -cleared contraceptive supplies and services without cost sharing. In contrast to coverage under Medicaid or private insurance, people with Medicare can face out-of-pocket costs for visits to insert or remove long-acting reversible methods such as IUDs and implants.

- Female sterilization (e.g., tubal ligation) for females is covered under Medicare only when it is necessary as part of the treatment of an illness or injury. However, under Medicaid and most private plans, the procedure is covered without cost sharing.

- The Hyde Amendment prohibits federal funds from being used to cover abortions under Medicare except if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest or when the pregnancy poses a threat to the life of the pregnant person.

- Medicare, unlike Medicaid, requires cost sharing for pregnancy-related services and, unlike private plans, typically requires cost sharing for prenatal visits and related services including breastfeeding support and supplies.

- Nearly 8 in 10 (79%) women of reproductive age with Medicare are also covered by Medicaid, which gives them broader coverage of sexual and reproductive health services relative to having Medicare alone. In addition, most dual-eligible individuals receive assistance with their Medicare Part A and B cost sharing, meaning they do not pay out-of-pocket for Medicare services that require cost sharing, and also receive subsidies that help pay their cost sharing for contraceptive products covered under Part D.

Introduction

Medicare is the federal program that provides health insurance coverage to 66 million people, including over 35 million women. While Medicare primarily covers people ages 65 and older, it also covers people under age 65 with long-term disabilities, including 1.1 million women of reproductive age (ages 20-49) in 2022. (For state-level estimates of women of reproductive age, see Table 1.) Women with disabilities have unique health needs and experience greater disparities in health outcomes and access to care, such as physical barriers for those with mobility impairments and a shortage of clinicians with expertise in caring for people with a disability. Misperceptions about the sexual health needs and preferences of women with disabilities may also result in patients not getting needed care or their preferred form of contraception. People who are under age 65 covered by Medicare report worse access to care, more cost concerns, and lower satisfaction than people with Medicare ages 65 and older, yet are often overlooked in discussions about Medicare and ways to make the program work better for beneficiaries.

While Medicare covers a broad range of health and medical care services, it was not originally designed to meet the specific health care needs of people under age 65 with long-term disabilities, including sexual and reproductive health care for women of reproductive age, since Medicare eligibility for people under age 65 was added several years after the program’s creation. Addressing this gap may be part of the impetus behind the executive order issued by President Biden in June 2023 directing the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to take steps to improve Medicare coverage of contraceptives. The Biden Administration has recently updated the formulary review process for coverage of contraception under the Medicare Part D drug benefit, which could increase coverage of additional types of contraception for people with Medicare, specifically intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants.

This brief describes Medicare coverage of sexual and reproductive health services for women and others capable of becoming pregnant. It also compares Medicare coverage with what is required by federal law under private insurance plans and Medicaid, the federal-state health coverage program for people with low incomes. (KFF recognizes that some individuals who require contraception and other reproductive health care services may not self-identify as women. The language used here attempts to be as inclusive as possible, but some of the analysis is based on survey data that uses specific gender labels for female and male for the data year analyzed for this brief, and may not be inclusive of gender non-binary, transgender, and other gender expansive identities.)

A Profile of Reproductive-Age Women with Medicare

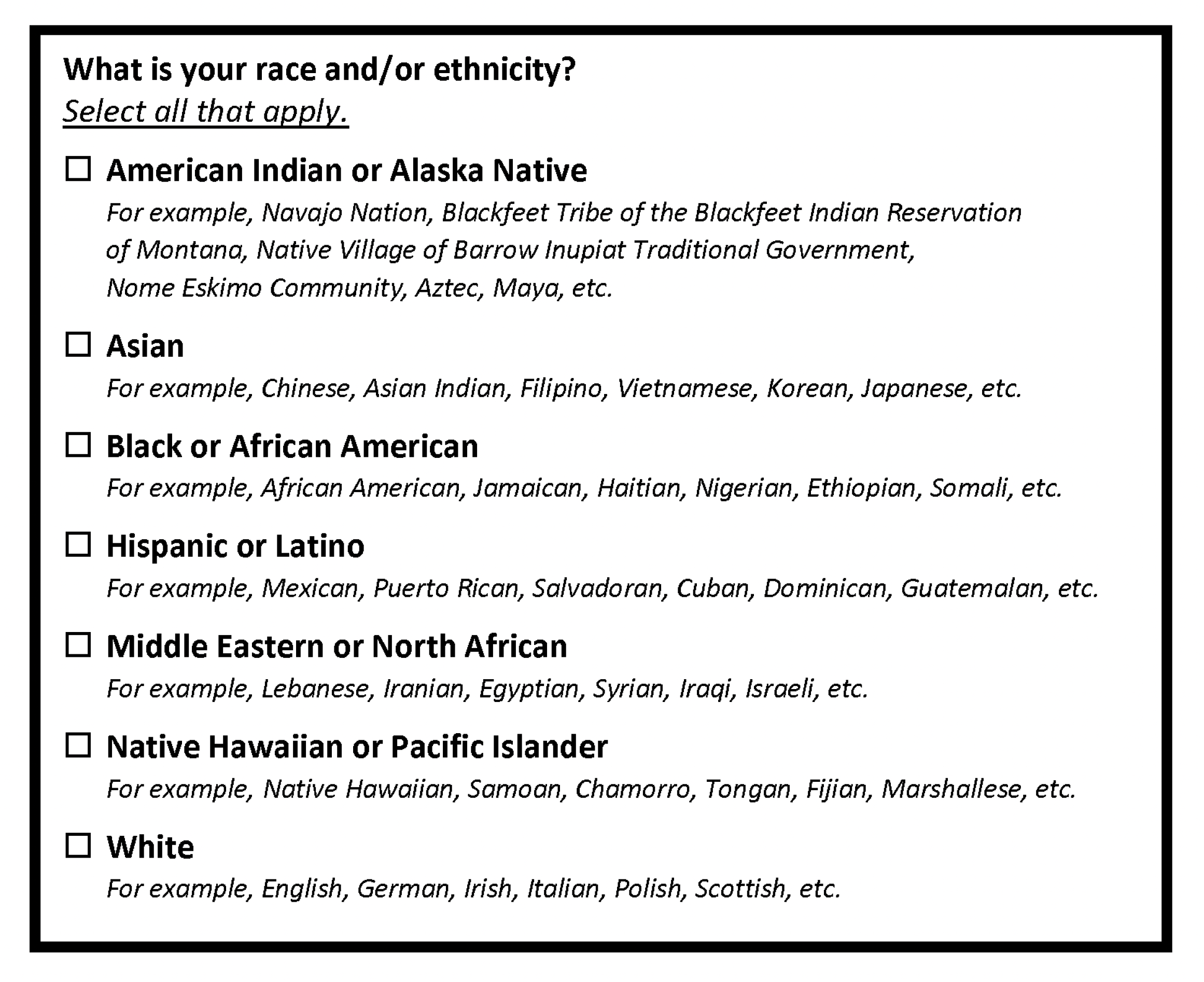

Women of reproductive age (ages 20 to 49) with Medicare are more likely than women ages 65 and older with Medicare to be Black or Hispanic, have lower incomes, be in worse health, and experience functional and cognitive impairment (Figure 1). (These estimates are based on KFF analysis of 2021 data from the CMS Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.)

Race/Ethnicity. A larger share of women of reproductive age than women 65 and older with Medicare are Black (20% vs 9%, respectively) and Hispanic (14% vs 9%, respectively).

Income. A much larger share of reproductive-age women enrolled in Medicare have low incomes compared to women 65 and older. For example, nearly three-quarters (73%) of women ages 20-49 have incomes of less than $20,000 per year compared to 28% of women ages 65 and older.

Health Status. Because eligibility for Medicare for those under age 65 generally depends on having a long-term disability, a larger share of reproductive-age women has significant health problems or functional limitations compared to women with Medicare ages 65 and older. Slightly less than half of women of reproductive age (44%) rate their health status as fair or poor compared to 16% of older women, 44% have a limitation in activities of daily living compared to 26% of older women, and 57% have a cognitive impairment compared to 14% of older women.

Sources of Coverage. Among the nearly 1 million women of reproductive age enrolled in Medicare Part A and Part B in 2021, close to 6 in 10 (57%) were covered under traditional Medicare and 43% were enrolled in Medicare Advantage plans (Figure 2). A somewhat smaller share of women 65 and older with Medicare are enrolled in traditional Medicare and a somewhat larger share in Medicare Advantage (52% and 48%, respectively).

Nearly 8 in 10 (79%) women of reproductive age with Medicare are also covered by Medicaid, the federal-state health program for people with low incomes, whereas a relatively small share of women 65 and older with Medicare also have Medicaid (16%). This reflects the fact that most women of reproductive age in Medicare have low incomes. Among women of reproductive age with both Medicare and Medicaid (known as dual-eligible individuals), in 2021, 60% were in traditional Medicare and 40% in Medicare Advantage, whereas among those age 65 and older, the pattern was reversed (37% in traditional Medicare vs. 63% in Medicare Advantage) (data not shown).

Most women of reproductive age who are dual-eligible individuals qualify for full Medicaid benefits, which gives them enhanced coverage of sexual and reproductive health services relative to having Medicare alone, as described in more detail below (see How Does Coverage of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Compare Between Medicare and Medicaid?).

Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Covered by Medicare

Medicare covers many sexual and reproductive health services for women, including preventive care and screenings, maternity care, and contraceptive coverage. Medicare Advantage plans, the private alternative to traditional Medicare that provided coverage to 43% of reproductive-age women with Medicare in 2021, are required to cover all benefits covered under traditional Medicare. Most Medicare Advantage plans also cover Part D outpatient prescription drugs, whereas for people with traditional Medicare, prescription drugs are generally covered under stand-alone Part D prescription drug plans (PDPs).

Preventive Care

Evidence-based preventive services can improve health by preventing the onset of certain conditions or by identifying health conditions earlier when they can be managed more effectively. While Medicare has long provided coverage of many preventive services, the Affordable Care Act requires that Medicare cover many of these services without cost sharing if the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) determines that they are reasonable and necessary for the prevention or early detection of an illness or disability, and appropriate for individuals in traditional Medicare.

Wellness Visits

Medicare Part B covers, without cost sharing, one “Welcome to Medicare” preventive visit within the first 12 months of being enrolled in Medicare, which includes a review of the beneficiaries’ medical and social history related to their health. After their first 12 months in Medicare, beneficiaries are eligible for a free yearly “Wellness” visit to develop or update a personalized plan to help prevent disease or disability, based on current health and risk factors.

Breast Cancer Screenings and Preventive Medications

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends routine screening mammograms every two years for women ages 50 to 74 to detect breast cancer, depending on risk factors. Medicare covers one baseline mammogram to screen for breast cancer or women between ages 35 to 39, as well as screening mammograms once every 12 months for women ages 40 and older without cost sharing under Part B. Diagnostic mammograms may be covered more than once a year, if medically necessary, but typically with cost sharing. For diagnostic mammograms, after the Part B deductible is met, 20% coinsurance applies.

Preventive medications such as tamoxifen and raloxifene can reduce the risk of breast cancer for those who are at high risk. These medications are covered under Part D (both stand-alone drug plans for those in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage drug plans), with cost-sharing amounts varying by drug and by plan.

Cervical and Vaginal Cancer Screening

The USPSTF recommends routine cervical cancer screenings for women ages 21 to 65. The recommended frequency ranges from every three years to every five years depending on the person’s age and the type of screening test. Medicare covers pelvic exams and Pap tests to check for cervical and vaginal cancers, once every 24 months, including for women over 65. For women at high risk for cervical or vaginal cancer, or for women of child-bearing age who had an abnormal Pap test in the past 36 months, Medicare covers these screening tests once every 12 months. Medicare also covers Human Papillomavirus (HPV) tests (as part of a Pap test) once every 5 years for women ages 30 to 65 without HPV symptoms. These tests and exams for cervical and vaginal cancers are covered under Part B without cost sharing.

HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections and Preventive HIV Medications

Routine screenings for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) such as chlamydia and herpes are important for early detection, treatment, and preventing transmission. Screenings for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections and counseling services are covered with no cost sharing under Medicare Part B.

Medicare covers HIV screening once per year for people who meet one of the following conditions:

- Ages 15 to 65.

- Younger than age 15 or older than age 65 and at an increased risk for HIV.

- Pregnant people can get screened up to 3 times during their pregnancy.

Medicare also covers sexually transmitted infection screenings for chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis, and Hepatitis B for pregnant people at certain times during their pregnancy and for people at increased risk for a sexually transmitted infection, once every 12 months. Medicare also covers up to 2 face-to-face, high-intensity behavioral counseling sessions for sexually active adults at increased risk for these infections.

For individuals who are at higher risk for HIV, use of pre-exposure prophylaxis medication, or PrEP, is a highly effective option to prevent infection. Medicare has proposed a national coverage determination that would make PrEP a Part B preventive service, which would make it available at no cost for beneficiaries who qualify. Medicare also proposed to cover up to seven counseling visits per year, HIV screenings up to seven times per year, and a screening for hepatitis B. Currently, antiretrovirals (ARVs) used for PrEP are covered under both Medicare Part D for oral medications and Part B for injectable physician-administered medications. The NCD would streamline coverage of these services under Part B.

Contraception

Coverage of Contraception Under Part B

Most sexually active females ages 18 to 49 use some form of contraception. While most use contraception to prevent pregnancy, some use it to manage a medical condition or in the case of condoms, to prevent the transmission of STIs. With limited exceptions, Medicare Part B generally does not cover contraception for the sole purpose of preventing pregnancy (unlike coverage under Part D; see below for details).

Under Medicare Part B, IUDs may be covered but coverage is limited to some menstrual illnesses, including to treat endometrial hyperplasia. When IUDs are covered under Part B, Medicare would cover the device and costs for insertion and removal by a physician, but cost sharing would still apply.

Female sterilization (e.g., tubal ligation) is a permanent contraceptive method used to prevent pregnancy. Sterilization is not covered by Medicare as an elective procedure, nor if a physician believes that a future pregnancy would endanger the overall health of the woman. When covered, whether the service falls under Part A or Part B depends on whether the procedure was performed on an inpatient or outpatient basis and would be subject to cost sharing.

Coverage of Contraception Under Part D

Since the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit took effect in 2006, contraceptive products have been covered by stand-alone Part D prescription drug plans and Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans, but not all types of contraception have been covered by all Part D plans. Until recently, not all forms of contraception were listed on the Part D formulary reference file, which is a list of drugs that may be (though are not all required to be) included on Part D formularies. The Biden Administration has recently taken steps to update the formulary review process in Part D for coverage of contraception, based on widely-accepted clinical guidelines, which could increase access to more types of contraception. While the formulary reference file is not a Part D coverage list, plan formularies must include different types of contraceptives that meet widely accepted clinical treatment guidelines and evidence. As of 2024, the Part D formulary reference file includes IUDs and implants, in addition to contraceptive pills, patches, rings, and injections that were already listed on the formulary reference file.

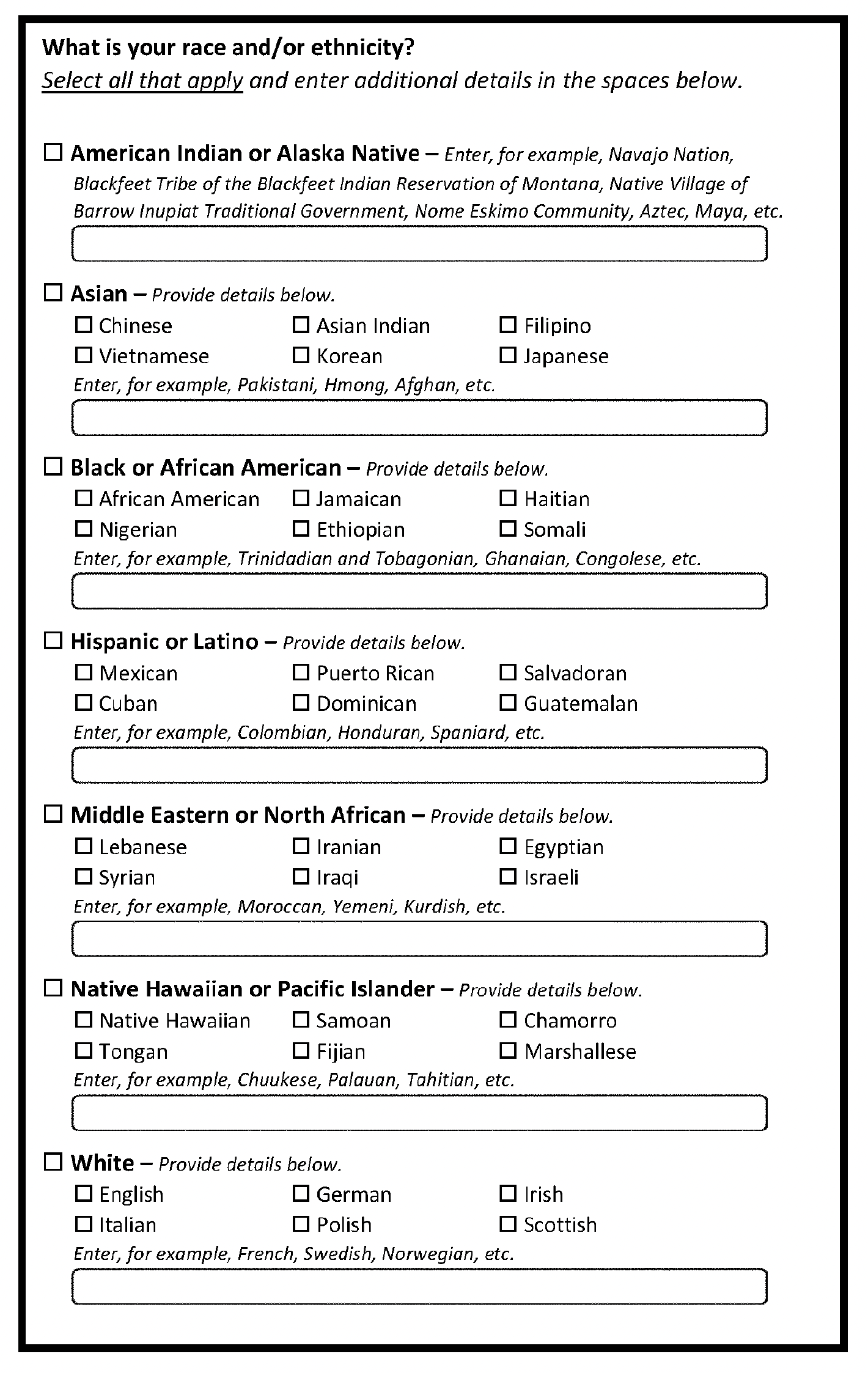

Coverage and cost sharing for specific contraceptives vary across Medicare Part D plans. In general, Part D coverage of IUDs and contraceptive implants is not widespread in 2024, though most Part D enrollees are in plans that cover contraceptive pills, rings, patches, and injections (Figure 3).

When IUDs, implants, patches, rings, and injections are covered, they are typically placed on higher formulary tiers than oral contraceptives – most often on Tier 4 in the Part D plan’s formulary, which usually corresponds to the non-preferred drug tier and requires higher levels of cost sharing than other tiers (Figure 4). In contrast, for a select group of widely used oral contraceptives, around 4 in 10 Part D enrollees are in plans with coverage on Tier 1 or Tier 2, which typically correspond to generic drug tiers that require relatively low cost sharing.

The following examples illustrate the variation in potential cost sharing for selected contraceptive products faced by Medicare Part D enrollees who do not receive Part D low-income subsidies (LIS), which helps cover premiums and cost sharing for low-income enrollees:

- For the less than 1% of Part D enrollees with coverage of the Mirena IUD in 2024, over 90% are in plans where the drug is covered on Tier 4, which would translate to a copayment of $100 for most of these enrollees. (These costs do not include cost sharing for the physician visit required for insertion of the device). The Mirena IUD typically lasts for 8 years.

- For the 67% of enrollees who have coverage of the Xulane patch, nearly 90% are in plans where the drug is covered on Tier 4. Around half of these enrollees would face Tier 4 copayments of $100 for a month’s supply, while the others would face coinsurance of 50% for Tier 4 drugs, which translates to around $45 to $50 for Xulane depending on the retail price.

- For a selected group of contraceptive pills, which are covered nearly all Part D enrollees, around 4 in 10 enrollees are in plans where these drugs are covered on Tier 2, and most of these enrollees would face Tier 2 cost sharing of $10 for a month’s supply. However, if the retail cost of the drug is less than the copayment, enrollees would pay the lower cost. For example, the retail cost of Junel FE 1/20 is between $5 and $6 per one-month supply, so an enrollee would pay that lower amount rather than a $10 copayment.

As noted, these examples of cost sharing do not apply to Medicare Part D enrollees who receive Part D Low-Income Subsidies (LIS), which offers financial assistance with Part D plan premiums and cost sharing for beneficiaries with low incomes and assets. LIS enrollees face only modest copayments for prescriptions covered under Part D regardless of tier placement. Of note, dual-eligible individuals – a majority of all women of reproductive age with Medicare – automatically receive LIS. These subsidies are a valuable benefit to those who qualify. In 2024, Part D enrollees receiving LIS pay no more than $4.50 for generic and $11.20 for brand-name covered contraceptive products, regardless of which formulary tier the drugs are placed on by their plans, while non-LIS enrollees would face higher cost sharing depending on the specific product and tier placement, as explained above.

It is not yet clear whether or how coverage will be provided for the insertion and/or removal of IUDs, implants, and other forms of longer-acting contraception when the device itself is covered under Part D for birth control.

Abortion

For nearly 50 years, since 1976, the Hyde Amendment has blocked federal funds from being used to cover abortions under all federal programs including Medicare except: 1) if the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest or (2) in the case where a woman suffers from a physical injury, including a life-endangering physical condition arising from the pregnancy itself, that could cause her death unless an abortion is performed. When covered, whether the service falls under Medicare Part A or Part B depends on whether the procedure was performed as inpatient (Part A) or outpatient (Part B).

In June 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, allowing states to prohibit or severely restrict abortion. In states where abortion is now banned, individuals covered by Medicare wanting or needing an abortion have few options: they can travel out of state or seek medication abortion pills via telehealth or from an online platform if it is still early in the pregnancy. In states that prohibit abortion, even exceptions for life endangerment of the pregnant person can be legally unclear. Doctors in these states may be hesitant to perform an abortion even for life endangerment due to concerns about legal risk.

Fertility Services

Treatments for infertility include fertility medications, artificial insemination, surgery, and in-vitro fertilization. According to the Medicare Benefit Policy Manual, “reasonable and necessary services associated with treatment for infertility are covered under Medicare [Part B].” However, specific covered services are not listed, and the definition of “reasonable and necessary” in this specific context is not defined. The 2003 law that established the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit explicitly prohibits Part D plans from covering fertility drugs, along with some other types of drugs, including those prescribed to treat sexual or erectile dysfunction.

A wide range of services are recommended to support the health of pregnant and postpartum individuals. Medicare covers “reasonable and necessary” services associated with pregnancy, including prenatal care, labor and delivery, and necessary postnatal care. Medicare Part A hospital insurance covers all pregnancy-related care when admitted to the hospital. Medicare Part B covers doctors’ visits and other outpatient services and tests related to pregnancy. All these services are subject to Medicare cost-sharing requirements.

Gender-Affirming Care

Gender-affirming care includes a spectrum of “social, psychological, behavioral or medical (including hormonal treatment or surgery) interventions designed to support and affirm an individual’s gender identity.”

While federal Medicare policy does not cover gender reassignment surgery for beneficiaries with gender dysphoria, local Medicare Administrative Contractors (MACs) may determine coverage of gender reassignment surgery on a case-by-case basis. Coverage may also include hormonal therapies such as estrogens and anti-androgens for male to female transitions and androgens and progestins for female to male transitions; such therapies would be covered under Part D, subject to each plan’s formulary coverage and cost-sharing requirements.

How Does Coverage of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Compare Between Medicare and Medicaid?

About 8 in 10 reproductive-age women (79%) with Medicare also have Medicaid coverage to help with the out-of-pocket costs of Medicare. Most of these women qualify for full Medicaid benefits, which gives them broader coverage of sexual and reproductive health services relative to having Medicare alone, as described below. In addition, most dual-eligible individuals receive assistance with their Medicare Part A and Part B cost sharing, meaning they do not pay out-of-pocket for Medicare services that require cost sharing, whether they receive their Medicare coverage through traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan. As noted earlier, dual-eligible individuals also receive Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidies, which offer financial assistance with Part D plan premiums and cost sharing.

Federal Medicaid rules allow states some flexibility to design their own benefit packages beyond meeting mandatory federal requirements, which include coverage for physician, family planning, and pregnancy-related services. Furthermore, individuals who qualify for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion option (now offered by 40 states and DC) requires coverage of “essential health benefits” including several specific services for women (for a discussion of Medicaid and women, see Medicaid Coverage for Women). While this coverage requirement typically only applies to ACA Medicaid expansion populations (generally, single individuals or married couples without children), most states have aligned the benefits to also include those who qualify for Medicaid under other coverage pathways.

In terms of coverage of sexual and reproductive health services, traditional Medicaid programs must cover family planning services broadly and states are permitted to define those services within that broad category, but cost sharing is prohibited for family planning services, including contraception. All state expansion programs must cover FDA-approved, -granted or -cleared contraceptives with a prescription, including long-acting contraception such as IUDs, implants, and sterilizations without cost sharing.

As under Medicare, the Hyde Amendment also limits Medicaid coverage of abortions to cases of rape, incest, or life endangerment of the pregnant person. However, 17 states use their own funds to pay for abortions for Medicaid enrollees in other (non-Hyde) circumstances.

Medicaid also covers pregnancy-related services, but unlike Medicare, federal law prohibits cost sharing for these services. Medicaid pays for over 4 in 10 births in the U.S. Beyond inpatient and outpatient hospital care, which must be covered, states can define the specific maternity services covered by Medicaid. Nearly all states provide comprehensive pregnancy-related benefits, including prenatal vitamins, ultrasounds, and postpartum visits. Breast pumps and lactation counseling are required benefits for individuals who qualify for the Medicaid expansion under the ACA, and most people who qualify for Medicaid through other eligibility pathways typically receive this benefit without cost sharing, which is not the case in the Medicare program.

While most reproductive-age women with Medicare are also enrolled in Medicaid, which should protect them from cost sharing relative to those who have Medicare alone, navigating coverage under these two different health care programs can be challenging, with varying levels of coordination across states and payors. Recognizing these challenges, federal and state governments are engaged in efforts to improve coordination of benefits between Medicare and Medicaid, but few dual-eligible individuals are enrolled in fully integrated plans and there are reports of difficulties in accessing coverage for contraceptives among dual-eligible individuals. A recent study of contraceptive use among women with disabilities found that those with Medicare alone had the lowest use of contraceptive care and while utilization was higher among dual-eligible individuals, utilization was highest among those with Medicaid alone.

How Does Coverage of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services Compare Between Medicare and Private Insurance?

Under a requirement of the ACA, individual and fully-insured small group health insurance plans must cover ten categories of “essential health benefits” such as prescription drug coverage, doctors’ services, maternity care, and hospital care. In addition, nearly all health insurance plans (including self-funded plans and large group plans) must also cover, without cost sharing, certain recommended preventive health services.

Like Medicare, private plans are required to cover certain preventive services for women such as annual check-ups and routine cancer screenings like mammograms and Pap tests without cost sharing. Coverage for maternity care is required to be covered in the individual and fully-insured small group markets as an essential health benefit but may be subject to cost sharing. The Pregnancy Discrimination Act effectively requires the health plans of employers with a minimum of 15 workers to cover pregnancy-related services, including maternity care. Nearly all private plans must also cover, without cost sharing, prenatal care visits (considered to be a type of well-women care) and preventive screenings recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force for pregnancy-related care and by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). In addition, plans must also cover without cost sharing pre-pregnancy, postpartum, and interpregnancy visits (defined as well woman care), and breastfeeding support services and supplies.

The preventive services coverage requirements also mandate that most private plans cover risk-reducing medications, such as tamoxifen, raloxifene, or aromatase inhibitors, to women ages 35 years and older who are at increased risk for breast cancer and at low risk for adverse medication effects. These medications are required to be covered for high-risk women without cost sharing. Under Medicare, these drugs are typically covered under Part D plans, but cost sharing can apply. Similarly, private plans must cover PrEP for individuals at high risk of acquiring HIV. Insurers must also cover at no cost baseline and monitoring services including HIV testing, Hepatitis B and C testing, creatinine testing and calculated estimated creatine clearance or glomerular filtration rate, pregnancy testing, STI screening and counseling, adherence counseling, as well as office visits associated with these services.

As discussed earlier, Medicare offers coverage for contraception, but the scope of coverage is not as comprehensive as that which is required in most private plans (with the exception of the plans of employers with religious objections to contraception and grandfathered plans). Under the ACA, most plans are required to include coverage of the full range of FDA-approved, -granted, or -cleared contraceptives, as well as effective family planning practices, and sterilization procedures, and they must be covered without cost sharing. This also includes coverage of counseling and device insertion and removal, without cost sharing, which is not the case under Medicare Part B or Part D.

In contrast to Medicare, which is subject to federal laws, state regulated private health insurance plans (individual plans and the fully-insured group markets) are subject to state insurance laws, in addition to the federal requirements. Although federal law does not require private plans to cover abortion, 10 states require this coverage for their state-regulated plans. Likewise, some states also require coverage of other sexual and reproductive health services not required by federal law such as certain infertility services, over-the-counter contraceptive methods without a prescription, and one state explicitly requires coverage of specific gender-affirming care services in its state-regulated plans.