The Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires insurers to report transparency data for all non-grandfathered health plans sold on and off the Marketplace, including fully-insured and self-insured employer group health plans. The law requires data to be available to federal and state insurance regulators and to the public. However, federal implementation of this requirement has so far been limited to qualified health plans (QHP) offered on the federally facilitated Marketplace (HealthCare.gov) and does not include QHPs offered on state-based Marketplaces or group health plans. This brief analyzes federal transparency data released by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) on claims denials and appeals for non-group qualified health plans (QHPs) offered on HealthCare.gov in 2023. A downloadable working file based on CMS’s public use file is available on the right-hand side of this brief.

Key Takeaways

- Insurers of qualified health plans (QHPs) sold on HealthCare.gov denied 19% of in-network claims in 2023 and 37% of out-of-network claims for a combined average of 20% of all claims.

- The in-network denial rate ranged from 1% to 54%. There was significant variation by insurer and by state.

- Of limited information available on in-network claims denial reasons, the most common reason cited by insurers was “Other” at 34% followed by administrative reasons (18%), excluded service (16%), lack of prior authorization or referral (9%), and only 6% based on lack of medical necessity.

- Consumers rarely appeal denied claims (fewer than 1% of denied claims were appealed) and when they do, insurers usually uphold their original decision (56% of appeals were upheld).

- Marketplace enrollees filed 5,000 external appeals in 2023, or 3% of all upheld internal appeals. Due to the suppression of small values, the rate at which external appeals were upheld could not be calculated.

Introduction

The impact of claims denial is widely recognized by enrollees. The 2023 KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance found that 58% of insured adults said they have experienced a problem using their health insurance, including denied claims. Four in ten (39%) of those who reported having trouble paying medical bills said that denied claims contributed to their problem.

As a part of the annual QHP certification process, issuers (referred to as insurers in this brief) must report certain denied claims information to CMS for plans that were offered in the previous year that they want to offer in the upcoming year. Data does not include information about denied requests for prior authorization (a claim decision made before a service is provided). The dataset only includes information about claims for benefits (medical and prescription drugs combined) made after a service was provided (post-service claims).

Insurers participating in the Marketplace in 2025 reported aggregated data on all HealthCare.gov QHPs they offered in 2023. Additionally, plan-level data from 2023 are reported for plans returning in 2025, including the number of in- and out-of-network claims submitted and denied, and reasons for claims denials. Among insurers participating in HealthCare.gov states in 2023, 43 are not participating in 2025 so they did not provide claims denial information. Among returning insurers, such denial information was only reported for 69% of their claims (the share of claims attributable to returning plans), as not all plans offered in 2025 were also offered in 2023. Additionally, only 40% of plans in the dataset were offered in 2023 and are included in the plan-level reporting for denial reasons. See the Methods and Data Limitations section for more details.

Claims Denials and Appeals in 2023

Insurer-level Claims Denials Data

Insurers reported receiving 425 million claims in 2023, with 92% (392 million claims) filed for in-network services. Of these in-network claims, 73 million were ultimately denied, resulting in an average in-network denial rate of 19% (Figure 1). Out-of-network claims totaled 33 million, with an overall higher denial rate of 37%. Claims that were initially denied then subsequently resubmitted and paid are not included as denied claims in the denial rate.

Although the composition of HealthCare.gov states has continued to change since the inception of transparency reporting, the overall in-network denial rate in 2023 is similar to those from other analyses conducted by KFF (Figure 2).

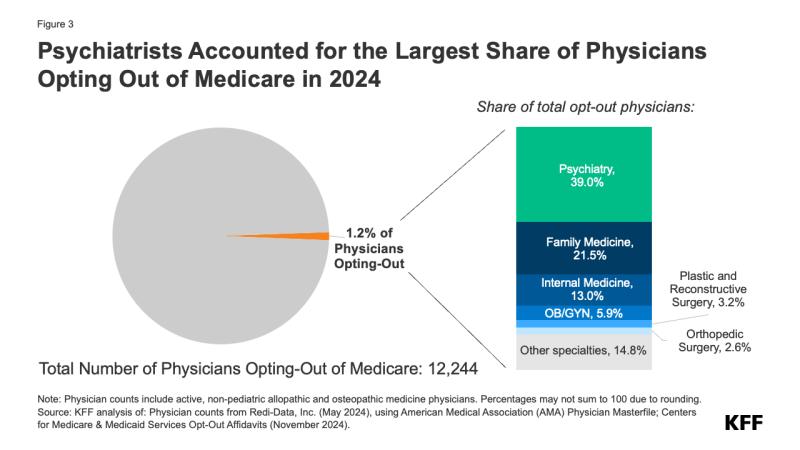

Insurer denial rates for in-network claims received in 2023 varied widely, ranging from 1% to 54%. Twenty-two of the 175 reporting insurers had an in-network denial rate of less than 10% while twenty-nine insurers had a denial rate of 30% or more (Figure 3).

Denial rates also varied geographically, as shown in Figure 4. The state with the highest average in-network denial rate for HealthCare.gov insurers was 34%, in Alabama, and the lowest was 6%, in South Dakota. Average denial rates have the potential to obscure variation. For example, while the average denial rate for insurers in Florida (16%) was slightly below the national average (19%), denial rates for insurers in Florida had more variability than another other state included in this analysis, ranging from 8% to 54% (the highest single insurer-level denial rate in the country).

Limited ACA transparency data collected by the federal government continue to show wide disparities in the rate at which Marketplace plans pay claims. While HealthCare.gov insurers denied an average of 19% of in-network claims in 2023, some insurers reported denying a much higher share. Table 1 shows denial rates for claims filed by parent companies that received more than 5 million claims within HealthCare.gov states in 2023. For in-network claims processed by these parent companies, the average in-network denial rate was 19%, ranging from 13% to 35% by parent company. (Blue Cross and Blue Shield parent companies from different states are separated in this table because they operate independently.)

Plan-level Claims Denial Data

In all, insurers reported on 49 million denied in-network claims at the plan level for the 2023 coverage year. Denial rates varied only slightly between most plan metal levels. On average, in 2023, HealthCare.gov insurers denied 19% of in-network claims in their bronze plans, 18% in silver plans, 18% in gold plans, 15% in platinum plans, and 27% in catastrophic plans (Figure 5).

CMS requires HealthCare.gov insurers to report the reasons for in-network claims denials at the plan level. Specified denial reason categories include:

- Denials due to lack of prior authorization or referral

- Denials due to an out-of-network provider

- Denials due to an exclusion of a service

- Denials based on medical necessity (reported separately for behavioral health and other services)

- Denials due to enrollee benefit reached

- Denials due to a member not being covered

- Denials due to investigational, experimental, or cosmetic procedure

- Denials for administrative reasons (which include claims that were duplicate, missing information, untimely, for an unapproved provider, or that met other criteria)

- Denials for all other reasons not specified above.

Denials due to enrollee benefit reached (such as a limit on the number of physical therapy visits allowed per year); member not being covered at the time of service; investigational, experimental, or cosmetic procedure; and administrative reasons were reported on for the first time for 2022 data (in filings for application for the 2024 plan year).

A claim might be denied for more than one reason and on more than one submission. For example, if the initial submission of a claim misspelled a patient’s name and was denied because the patient could not be identified, the claim may be denied again after being corrected and resubmitted if the claim were for a service that was not covered. Additionally, denial reasons are also reported for claims that are ultimately paid if they are resubmitted to correct the deficit or are successfully appealed. Insurers reported about 71 million denial reasons for in-network claims that were denied at some point in the adjudication process. The adjudication process employed by the insurer may affect how denial reasons are reported. Although publicly reported data allow for multiple reasons throughout the life of a claim, in practice, insurers may file denial reasons sequentially and not capture all applicable reasons for denying claims, such as denying claims from an unidentifiable enrollee before determining whether the claim was for a medically necessary procedure.

The distribution of in-network denials by reason is shown in Table 2. Of in-network claims, about 16% of denials were because the claim was for an excluded service, 9% due to lack of prior authorization or referral, and only about 6% based on medical necessity. The share of denial reasons related to administrative reasons is 18%, the most common reason aside from “other” (34%). The share of denial reasons attributed to “other” reasons in 2023 is significantly smaller compared to the 2021 data due to the reporting of new specific denial reasons, notably administrative reasons. Among all in-network claims filed, 6% required a resubmission (not necessarily for administrative reasons though). A resubmission may occur when the original claim was incomplete, contained errors, or was rejected for non-compliance with billing guidelines.

Insurers also had wide variability in their use of denial reasons. While about 6% of all in-network claims denials by HealthCare.gov plans were based on medical necessity, several plans reported much higher shares for medical necessity reasons. For example, 30% of denial reasons for Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina were due to medical necessity. Similarly, while about 9% of all in-network denials by HealthCare.gov plans were based on lack of prior authorization or referral, some plans reported a much larger share. For example, 97% of denial reasons for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona were for lack of prior authorization or referral.

Plans may apply utilization review techniques differently. For example, individual insurer policies and practices may affect the balance between denials for failure to obtain referral/prior authorization and medical necessity denials, as greater use of prior authorization would shift utilization review to before a service is provided and possibly decrease the number of denials due to medical necessity. However, without more detail on the types of claims subject to these denials, it is not possible to discern the possible implications for patients. Recent federal regulations may provide further insight into the prior authorization process and what services typically require prior authorization for Healthcare.gov plans. Furthermore, denials captured in this data do not reflect the share or types of services covered by insurers.

Appeals Data

CMS requires insurers to report the total number of denied and internally appealed claims at the insurer level. Internal appeal is a process that allows a consumer to challenge a denied claim made by their health insurer. As in KFF’s previous analysis of federal claims denial data, we find that consumers rarely appeal denied claims and when they do, insurers usually uphold their original decision.

Appeal to Insurer (Internal Appeal). Of the 73 million in-network denied claims in 2023, HealthCare.gov consumers appealed 376,527 – an appeal rate of less than 1%. Insurers upheld 211,393 (56%) denials on appeal. Relatedly, the 2023 KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance found that only one in ten insured adults who reported experiencing a problem with their insurance in the past year had filed a formal appeal.

Appeal to Third Party (External Appeal). Consumers whose denial is upheld at internal appeal may have the right to an independent external appeal (also called external review) for certain types of claims. Among insurers that reported at least 10 external appeals in 2023, Marketplace enrollees externally appealed at least 5,000 claims in 2023 (CMS suppresses reporting of observations lower than 10 so the number of externally appealed claims could be higher). Among insurers that reported at least 10 external appeals in 2023, 3% of upheld appeals were externally appealed. Due to the suppression of small values, the rate at which external appeals were upheld could not be calculated.

It is not well known that consumers can appeal claims denials through an external appeal process. KFF’s 2023 consumer survey found that just 40% of consumers believed they have a legal right to appeal to a government agency or independent medical expert, while 51% said they were unsure if they had appeal rights, and 9% did not believe they had this right. Furthermore, Marketplace enrollees (34%) were less likely to know they had external appeal rights compared to those with Medicare (58%) and Medicaid (45%).

Other Data Sources

Absent data on how often insurers in other markets deny claims, it is difficult to put ACA transparency data in context. Below are other sources of claims denial data.

Covered California

California requires insurers to report data on claims received and denied each year for both in- and out-of-network services, in a manner similar to HealthCare.gov insurers. Among insurers submitting complete 2023 claims data to Covered California, the in-network denial rate was 21%, similar to HealthCare.gov insurers. One insurer had a denial rate of 87%. When excluding this insurer from the analysis, the overall claims denial rate among Covered CA insurers was 19%.

Specified denial reason categories are the same for both Marketplaces. At the plan-level, about 14% of in-network denials were due to lack of prior authorization or a referral, followed by about 6% due to administrative reasons, and about 1% for lacking medical necessity.

The appeal rate for Covered CA insurers (1%) was similar to HealthCare.gov insurers. Among all Covered CA insurers with complete data, about 40% of internal appeals and 47% of external appeals filed were upheld, substantially lower than HealthCare.gov insurers. Like denials, one insurer also represented a large share of the appeals data reported. When excluding that insurer, the rate of internal appeals upheld by Covered CA insurers was 61%.

Connecticut Health Insurance Report Card

Connecticut law requires private health insurers in all market segments with at least 1,000 enrollees to report annual data on claims payment practices, prior authorization requests and denials, claims denial reasons, and several other metrics (Table 3). The state insurance department publishes the aggregated data at the insurer level in its annual Consumer Report Card, which includes data from the largest insurer and is intended to inform consumer decision-making. Claims denial data include the total number of claims received and the total number of claims denied by reason.

Insurers in Connecticut reported receiving more than 11.8 million claims and denying more than 2.7 million claims in 2023, for an overall denial rate of 23%. In 2023, the largest shares of claims denials were for reasons related to the benefit not being covered (11.4% of denials) and for other reasons not specified (62.4%).

Connecticut’s claims denial data are not directly comparable to those reported by Covered CA or HealthCare.gov insurers for several reasons, including that Connecticut’s data includes group health plans, denial reasons are reported at the insurer level rather than the plan level, and claims data in Connecticut are not separated by network status.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), via the Market Conduct Annual Statement (MCAS), collects uniform data annually on claims denials, prior authorization requests, appeals, and more from many insurers in the individual and group markets in nearly every U.S. state. MCAS data are intended to help state insurance regulators monitor the market conduct of insurance companies, and insurers can use this information to identify areas to improve performance. However, full MCAS health insurance data are shared with state regulators only, not the general public or CMS. A limited national summary published by the NAIC shows that the average claims denial rate for both in- and out-of-network claims (excluding pharmacy) in 2023 was about 16%.

Medicare Advantage and Medicaid Managed Care

Medicare Advantage plans have come under scrutiny in recent years over concerns about policies and processes related to claims and prior authorization denials. According to a 2024 KFF analysis of federal data, Medicare Advantage plans denied (fully or partially) 3.4 million prior authorization requests for health care services in 2022, for an overall denial rate of about 7%, a share that has increased over the past few years. (Prior authorization is a process used by health insurers that requires providers to obtain approval before a service or other benefit is covered.) Additionally, a 2018 federal report found that 8% of claims and prior authorization requests (combined) submitted to Medicare Advantage plans between 2014 and 2016 were denied by insurers, which was less than half the denial rate reported, on average, by HealthCare.gov insurers during that period.

Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) also may require prior authorization. A 2023 federal report found that Medicaid MCOs denied more than 2 million prior authorization requests in 2019 for an overall prior authorization denial rate of nearly 13%–more than 2 times higher than the Medicare Advantage rate. However, these data are not directly comparable to the HealthCare.gov data being analyzed for this report, as the former pertains specifically to prior authorization denials while the latter covers post-service claims denials.

Looking Forward

Although research and investigations into health insurer practices have garnered attention from lawmakers and patient advocates over the past several years, the December 2024 killing of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO ignited broad public outrage over insurer claims denials. According to a January 2025 KFF public opinion poll asking about certain health care priorities for Congress and the Trump administration, most people (55%) say more closely regulating insurers’ decisions to approve or deny claims for health services or prescription drugs should be a “top priority.” While prospects for significant changes in response to the public outrage may be limited, interest in providing the public with more transparency about how insurer claims review and appeals operate could, in the same way as providing more accurate price transparency information, better enable consumers and employers to make more informed choices when purchasing private coverage. Efforts might include:

Including more specific information in existing datasets.

Using the current data, the proportion of claims denied for a given reason cannot be calculated. For example, it is not possible to know the share of services that were denied due to a lack of medical necessity. Federal reporting on denials could be more useful when presented as claims ever denied for a given reason, instead of tallying the total reasons. Also, reporting that includes denial information about all claims from all insurers in the previous year, and not just those attributable to plans that are returning to the Marketplace next year, could be useful. Additionally, information about the types of services approved and denied (e.g., specialty of service and type of prescription drug) would give a more comprehensive picture of insurer practices and what type of care was actually covered by an insurer or employer. Information about appeals, especially external appeals, could provide insight into how this consumer protection mechanism is working for patients. Information about what services required prior authorization and how often the prior authorization itself is approved and denied is another data element not included in the CMS Marketplace public use file but is included in NAIC MCAS data not available to the public.

Providing claims denial information about employer coverage.

Employer-sponsored insurance covered 154 million people under 65 in 2023. Since most Americans have employer-sponsored coverage, efforts to provide more information to this group may be a way to begin to address concerns about insurer denials. A proposed regulation from 2016 that was never finalized would have added a claims denial metric to reporting required under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA). Also, in 2024, some members of Congress, urged the Department of Labor (DOL) to collect information on claims and claims denial, citing reports of “widespread denials of health benefits.” An outside advisory panel to DOL also recently issued recommendations for increased data collection, among other claims and appeal reforms in this area. Also, federal mental health parity regulations updated in 2024 will require employer plans (and non-group plans) to collect and evaluate certain data, including the number and percentage of certain claims denials.

State-level initiatives.

There has been some activity at the state level to provide more transparency into claims denials and prior authorization requests. For example, in addition to California’s and Connecticut’s requirements for reporting claims denial data, Vermont requires insurers of state-regulated plans to report certain pre- and post-service claims denial data to the state, including breakdowns by mental health, substance use disorder services, and prescription drugs. Insurers in Oregon are required to report to the state claims denial and appeals data for behavioral health services compared to certain medical and surgical services. Additionally, Washington state requires insurers to report certain data related to prior authorization requests to the state, issue prior authorization determinations within certain timeframes, and use a standardized and streamlined prior authorization process. All of these states make at least some of this information available to the public annually. Going forward, more states may act to enact similar initiatives at the state level. These state laws, however, do not apply to self-insured health plans sponsored by private employers, which cover most insured Americans under age 65. Absent more uniform and complete data at a national level, efforts to fully understand and address issues related to health insurance claims denials will remain limited.

Methods and Data Limitations

Our analysis of the CMS Transparency in Coverage Public Use File includes insurers with more than 1,000 claims submitted and excludes stand-alone dental plans and small group (SHOP) plans. Of the 206 major medical insurers offering plans in 2025 in HealthCare.gov states, 175 reported receiving more than 1,000 claims and show data on claims received and denied. Among insurers participating in HealthCare.gov states in 2023, 43 are not participating in 2025 so they did not provide claims denial information. Calculation of claims denial rates includes information provided by insurers on plans offered in 2023 but not in 2025. A claim may be initially denied, then resubmitted and approved; claims that are paid even after initial denial do not count as denied in the claims denial rate calculation.

Twenty-nine insurers offering plans in 2025 did not offer plans in 2023. Just under half (45%) of plans available in 2025 were not available in 2023 among states that offered plans on HealthCare.gov in both years; of the 6,126 plans offered in 2023, only 2,481 (40%) were offered in 2025 and are included in the plan-level reporting providing information on denial reasons. Half of returning insurers did not provide statistics on denial reasons for more than 21% of claims filed in 2023, as they were associated with plans not being offered in 2025.

Calculation of denial reasons excluded claims that were denied as out-of-network in all totals. Since out-of-network denials may depend more on plan type than insurer processes, the analysis focused on in-network claims. Claims that are denied do not necessarily indicate that services are not ultimately paid by the insurer, such as when a new claim is filed instead of resubmitted.

The external appeal rate assumes that all external appeals went through an internal appeal first and was calculated as the number of external appeals filed over the number of internal appeals upheld. CMS suppresses reporting of values under 10. When calculating statistics with suppressed values, they were assumed to be zero. Additional considerations for using CMS transparency public files can be found here. To obtain the parent company name, the 2025 Qualified Health Plan landscape file was merged with the Medical Loss Ratio Submission Template header using HIOS plan identification numbers to find NAIC company codes. The NAIC identifier was then mapped to a parent company name using the Enrollment by Segment Exhibit data from Mark Farrah associates. A small number of insurers could not be mapped by this method and parent company names were entered manually. Statistics calculated at the parent company level do not include plans offered in segments other than on-exchange ACA plans offered in HealthCare.gov states.

Data from Covered California was compiled from reporting by insurer. Of the 11 insurers submitting data for the 2023 plan year, 8 submitted complete information and are included in our analysis. One insurer reported its plan-level claims data by benefit category (medical, pediatric vision and dental, and pharmacy) instead of by plan; from this data we calculated plan-level totals. We assume that other Covered CA insurers also included these four benefit categories when reporting their plan-level data as all four are considered Essential Health Benefits. Our analysis excludes stand-alone dental plans and small-group plans.