Children are now preparing to head back to school for the third time since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Schools are expected to return in-person this fall, with most experts now agreeing the benefits of in-person learning outweigh the risks of contracting COVID-19 for children. Though children are less likely than adults to develop severe illness, the risk of contracting COVID-19 remains, with some children developing symptoms of long COVID following diagnosis. COVID-19 vaccines provide protection, and all children older than 6 months are now eligible to be vaccinated. However, vaccination rates have stalled and remain low for younger children. At this time, only a few states have vaccine mandates for school staff or students, and no states have school mask mandates, though practices can vary by school district. Emerging COVID-19 variants, like the Omicron subvariant BA.5 that has recently caused a surge in cases, may pose new risks to children and create challenges for the back-to-school season.

Children may also continue to face challenges due to the ongoing health, economic, and social consequences of the pandemic. Children have been uniquely impacted by the pandemic, having experienced this crisis during important periods of physical, social, and emotional development, with some experiencing the loss of loved ones. While many children have gained health coverage due to federal policies passed during the pandemic, public health measures to reduce the spread of the disease also led to disruptions or changes in service utilization and increased mental health challenges for children.

This brief examines how the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect children’s physical and mental health, considers what the findings mean for the upcoming back-to-school season, and explores recent policy responses. A companion KFF brief explores economic effects of the pandemic and recent rising costs on households with children. We find households with children have been particularly hard hit by loss of income and food and housing insecurity, which all affect children’s health and well-being.

Children’s Health Care Coverage and Utilization

Despite job losses that threatened employer-sponsored insurance coverage early in the pandemic, uninsured rates have declined likely due to federal policies passed during in the pandemic and the safety net Medicaid and CHIP provided. Following growth in the children’s uninsured rate from 2017 to 2019, data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) show that the children’s uninsured rate held steady from 2019 to 2020 and then fell from 5.1% in 2020 to 4.1% in 2021. Just released quarterly NHIS data show the children’s uninsured rate was 3.7% in the first quarter of 2022, which was below the rate in the first quarter of 2021 (4.6%) but a slight uptick from the fourth quarter of 2021 (3.5%), though none of these differences are statistically significant. Administrative data show that children’s enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP increased by 5.2 million enrollees, or 14.7%, between February 2020 and April 2022 (Figure 1). Provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) require states to provide continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees until the end of the month in which the public health emergency (PHE) ends in order to receive enhanced federal funding.

Children have missed or delayed preventive care during the pandemic, with a third of adults still reporting one or more children missed or delayed a preventative check-up in the past 12 months (Figure 2). However, the share missing or delaying care is slowly declining, with the share from April 27 – May 9, 2022 (33%) down 3% from almost a year earlier (July 21 – August 2, 2021) according to KFF analysis of the Household Pulse Survey. Adults in households with income less than $25,000 were significantly more likely to have a child that missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months compared to households with income over $50,000. These data are in line with findings from another study that found households reporting financial hardship were significantly more likely to report missing or delaying children’s preventive visits compared to those not reporting hardships. Hispanic households and households of other racial/ethnic groups were also significantly more likely to have a child that missed, delayed, or skipped a preventive appointment in the past 12 months compared to White households (based on race of the adult respondent).

Telehealth helped to provide access to care, but children with special health care needs and those in rural areas continued to face barriers. Overall, telehealth utilization soared early in the pandemic, but has since declined and has not offset the decreases in service utilization overall. While preventative care rates have increased since early in the pandemic, many children likely still need to catch up on missed routine medical care. One study found almost a quarter of parents reported not catching-up after missing a routine medical visit during the first year of the pandemic. The pandemic may have also exacerbated existing challenges accessing needed care and services for children with special health care needs, and low-income patients or patients in rural areas may have experienced barriers to accessing health care via telehealth.

The pandemic has also led to declines in children’s routine vaccinations, blood lead screenings, and vision screenings. The CDC reported vaccination coverage of all state-required vaccines declined by 1% in the 2020-2021 school year compared to the previous year, and some public health leaders note COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy may be spilling over to routine child immunizations. The CDC also reported 34% fewer U.S. children had blood lead level testing from January-May 2020 compared to the same period in 2019. Further, data suggest declines in lead screenings during the pandemic may have exacerbated underlying gaps and disparities in early identification and intervention for lower-income households and children of color. Additionally, many children rely on in-school vision screenings to identity vision impairments, and some children went without vision checks while schools managed COVID-19 and turned to remote learning. These screenings are important for children in order to identify problems early; without treatment some conditions can worsen or lead to more serious health complications.

The pandemic has also led to difficulty accessing and disruptions in dental care. Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) show the share of children reporting seeing a dentist or other oral health provider or having a preventive dental visit in the past 12 months declined from 2019 to 2020, the first year of the pandemic (Figure 3). The share of children reporting their teeth are in excellent or very good conditions also declined from 2019 (80%) to 2020 (77%); the share of children reporting no oral health problems also declined but the change was not statistically significant.

Recently released preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under age 19 shows steep declines in service utilization early in the pandemic, with utilization then rebounding to a varying degree depending on the service type. Child screening services have rebounded to pre-PHE levels while blood lead screenings and dental services rates remain below per-PHE levels. Telehealth utilization mirrors national trends, increasing rapidly in April 2020 and then beginning to decline in 2021. When comparing the PHE period (March 2020 – January 2022) to the pre-PHE period (January 2018 – February 2020) overall, the data show child screening services and vaccination rates declined by 5% (Figure 4). Blood lead screening services and dental services saw larger declines when comparing the PHE period to before the PHE, declining by 12% and 18% respectively among Medicaid/CHIP children.

Children’s Mental Health Challenges

Children’s mental health challenges were on the rise even before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. A recent KFF analysis found the share of adolescents experiencing anxiety and/or depression has increased by one-third from 2016 (12%) to 2020 (16%), although rates in 2020 were similar to 2019. Rates of anxiety and/or depression were more pronounced among adolescent females and White and Hispanic adolescents. A separate survey of high school students in 2021 found that lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) students were more likely to report persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness than their heterosexual peers. In the past few years, adolescents have experienced worsened emotional health, increased stress, and a lack of peer connection along with increasing rates of drug overdose deaths, self-harm, and eating disorders. Prior to the pandemic, there was also an increase in suicidal thoughts from 14% in 2009 to 19% in 2019.

The pandemic may have worsened children’s mental health or exacerbated existing mental health issues among children. The pandemic caused disruptions in routines and social isolation for children, which can be associated with anxiety and depression and can have implications for mental health later in life. A number of studies show an increase in children’s mental health needs following social isolation due to the pandemic, especially among children who experience adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). KFF analysis found the share of parents responding that adolescents were experiencing anxiety and/or depression held relatively steady from 2019 (15%) to 2020 (16%), the first year of the pandemic. However, the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor on perspectives of the pandemic at two years found six in ten parents say the pandemic has negatively affected their children’s schooling and over half saying the same about their children’s mental health. Researchers also note it is still too early to fully understand the impact of the pandemic on children’s mental health. The past two years have also seen much economic turmoil, and research has shown that as economic conditions worsen, children’s mental health is negatively impacted. Further, gun violence continues to rise and may lead to negative mental health impacts among children and adolescents. Research suggests that children and adolescents may experience negative mental health impacts, including symptoms of anxiety, in response to school shootings and gun-related deaths in their communities.

Access and utilization of mental health care may have also worsened during the pandemic. Preliminary data for Medicaid/CHIP beneficiaries under age 19 finds utilization of mental health services during the PHE declined by 23% when compared to prior to the pandemic (Figure 4); utilization of substance use disorder services declined by 24% for beneficiaries ages 15-18 for the same time period. The data show utilization of mental health services remains below pre-PHE levels and has seen the smallest improvement compared to other services utilized by Medicaid/CHIP children. Telehealth has played a significant role in providing mental health and substance use services to children early in the pandemic, but has started to decline. The pandemic may have widened existing disparities in access to mental health care for children of color and children in low-income households. NSCH data show 20% of children with mental health needs were not receiving needed care in 2020, with the lowest income children less likely to receive needed mental health services when compared to higher income groups (Figure 5).

Children’s Health and COVID-19

While less likely than adults to develop severe illness, children can contract and spread COVID-19 and children with underlying health conditions are at an increased risk of developing severe illness. Data through July 28, 2022 show there have been over 14 million child COVID-19 cases, accounting for 19% of all cases. Among Medicaid/CHIP enrollees under age 19, 6.4% have received a COVID-19 diagnosis through January 2022. Pediatric hospitalizations peaked during the Omicron surge in January 2022, and children under age 5, who were not yet eligible for vaccination, were hospitalized for COVID-19 at five times the rate during the Delta surge.

Some children who tested positive for the virus are now facing long COVID. A recent meta-analysis found 25% of children and adolescents had ongoing symptoms following COVID-19 infection, and finds the most common symptoms for children were fatigue, shortness of breath, and headaches, with other long COVID symptoms including cognitive difficulties, loss of smell, sore throat, and sore eyes. Another report found a larger share of children with a confirmed COVID-19 case experienced a new or recurring mental health diagnosis compared to children who did not have a confirmed COVID-19 case. However, researchers have noted it can be difficult to distinguish long COVID symptoms to general pandemic-associated symptoms. In addition, a small share of children are experiencing multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a serious condition associated with COVID-19 that has impacted almost 9,000 children. A lot of unknowns still surround long COVID in children; it is unclear how long symptoms will last and what impact they will have on children’s long-term health.

COVID-19 vaccines were recently authorized for children between the ages of 6 months and 5 years, making all children 6 months and older eligible to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Vaccination has already peaked for children under the age of 5, and is far below where 5-11 year-olds were at the same point in their eligibility. As of July 20, approximately 544,000 children under the age of 5 (or approximately 2.8%) had received at least one COVID-19 vaccine dose. Vaccinations for children ages 5-11 have stalled, with just 30.3% have been fully vaccinated as of July 27 compared to 60.2% of those ages 12-17. Schools have been important sites for providing access as well as information to help expand vaccination take-up among children, though children under 5 are not yet enrolled in school, limiting this option for younger kids. A recent KFF survey finds most parents of young children newly eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine are reluctant to get them vaccinated, including 43% who say they will “definitely not” do so.

Some children have experienced COVID-19 through the loss of one or more family members due to the virus. A study estimates that, as of June 2022, over 200,000 children in the US have lost one or both parents to COVID-19. Another study found children of color were more likely to experience the loss of a parent or grandparent caregiver when compared to non-Hispanic White children. Losing a parent can have long term impacts on a child’s health, increasing their risk of substance abuse, mental health challenges, poor educational outcomes, and early death. There have been over 1 million COVID-19 deaths in the US, and estimates indicate a 17.5% to 20% increase in bereaved children due to COVID-19, indicating an increased number of grieving children who may need additional supports as they head back to school.

Looking Ahead

Children will be back in the classroom this fall but may continue to face health risks due to their or their teacher’s vaccination status and increasing transmission due to COVID-19 variants. New, more transmissible COVID-19 variants continue to emerge, with the most recent Omicron subvariant BA.5 driving a new wave of infections and reinfections among those who have already had COVID-19. This could lead to challenges for the back-to-school season, especially among young children whose vaccination rates have stalled.

Schools, parents, and children will likely continue to catch up on missed services and loss of instructional time in the upcoming school year. Schools are likely still working to address the loss of instructional time and drops in student achievement due to pandemic-related school disruptions. Further, many children with special education plans experienced missed or delayed services and loss of instructional time during the pandemic. Students with special education plans may be entitled to compensatory services to make up for lost skills due to pandemic related service disruptions, and some children, such as those with disabilities related to long COVID, may be newly eligible for special education services.

To address worsening mental health and barriers to care for children, several measures have been taken or proposed at the state and federal level. Many states have recently enacted legislation to strengthen school based mental health systems, including initiatives such as from hiring more school-based providers to allowing students excused absences for mental health reasons. In July 2022, 988 – a federally mandated crisis number – launched, providing a single three-digit number for individuals in need to access local and state funded crisis centers, and the Biden Administration released a strategy to address the national mental health crisis in May 2022, building on prior actions. Most recently, in response to gun violence, the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act was signed into law and allocates funds towards mental health, including trauma care for school children.

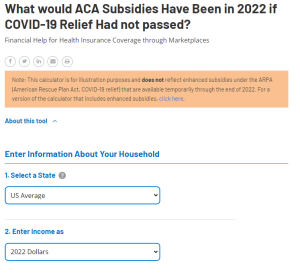

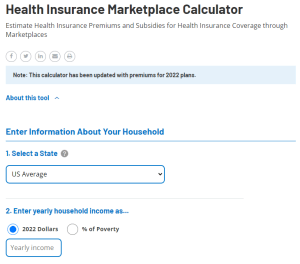

The unwinding of the PHE and expiring federal relief may have implications for children’s health coverage and access to care. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) extended eligibility to ACA health insurance subsides for people with incomes over 400% of poverty and increased the amount of assistance for people with lower incomes. However, these subsidies are set to expire at the end of this year without further action from Congress, which would increase premium payments for 13 million Marketplace enrollees. In addition, provisions in the FFCRA providing continuous coverage for Medicaid enrollees will expire with the end of the PHE. Millions of people, including children, could lose coverage when the continuous enrollment requirement ends if they are no longer eligible or face administrative barriers during the process despite remaining eligible. There will likely be variation across states in how many people are able to maintain Medicaid coverage, transition to other coverage, or become uninsured. Lastly, there have also been several policies passed throughout the pandemic to provide financial relief for families with children, but some benefits, like the expanded Child Tax Credit, have expired and the cost of household items is rising, increasing food insecurity and reducing the utility of benefits like SNAP.