KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: September 2022

Findings

Key Findings

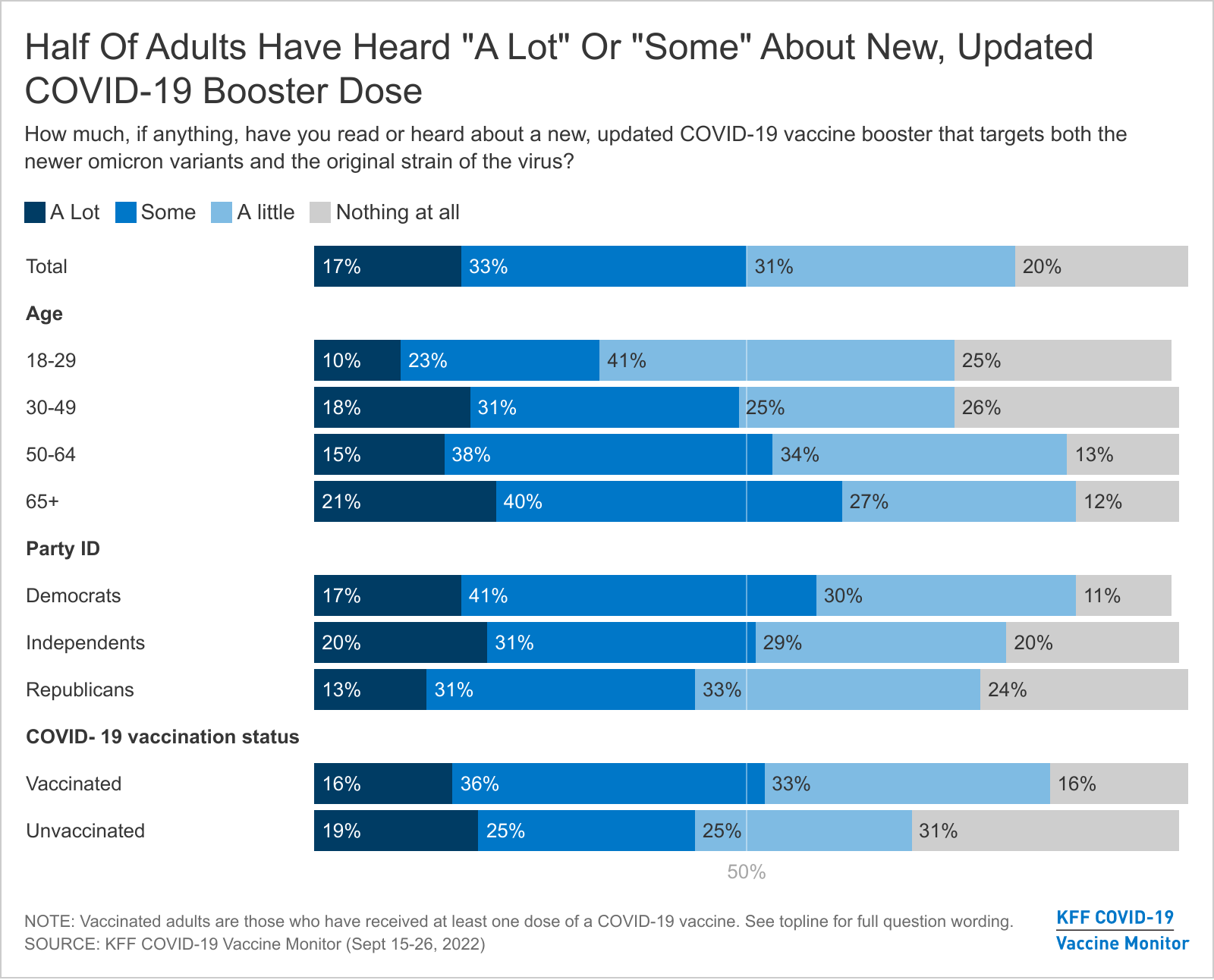

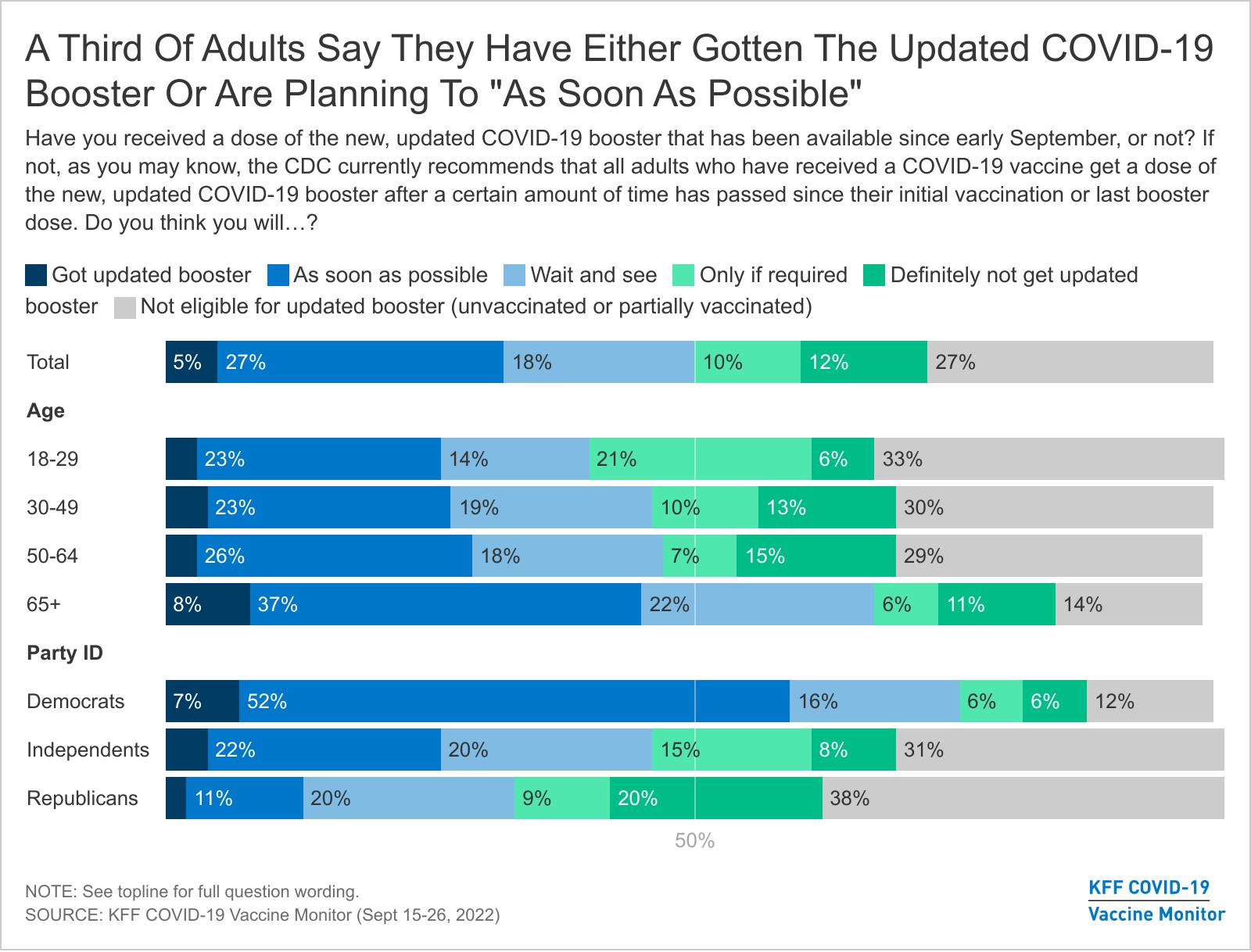

- The new, updated, bivalent COVID-19 boosters are now available for use, but the latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor survey finds that awareness of the updated boosters is relatively modest, with about half of adults saying they’ve heard “a lot” (17%) or “some” (33%) about the new shots. About a third of all adults (32%) say they’ve already gotten a new booster dose or intend to get one “as soon as possible.”

- Intention is somewhat higher among older adults, one of the groups most at risk for serious complications of a coronavirus infection. Almost half (45%) of adults ages 65 and older say they have gotten the bivalent booster or intend to get it “as soon as possible.”

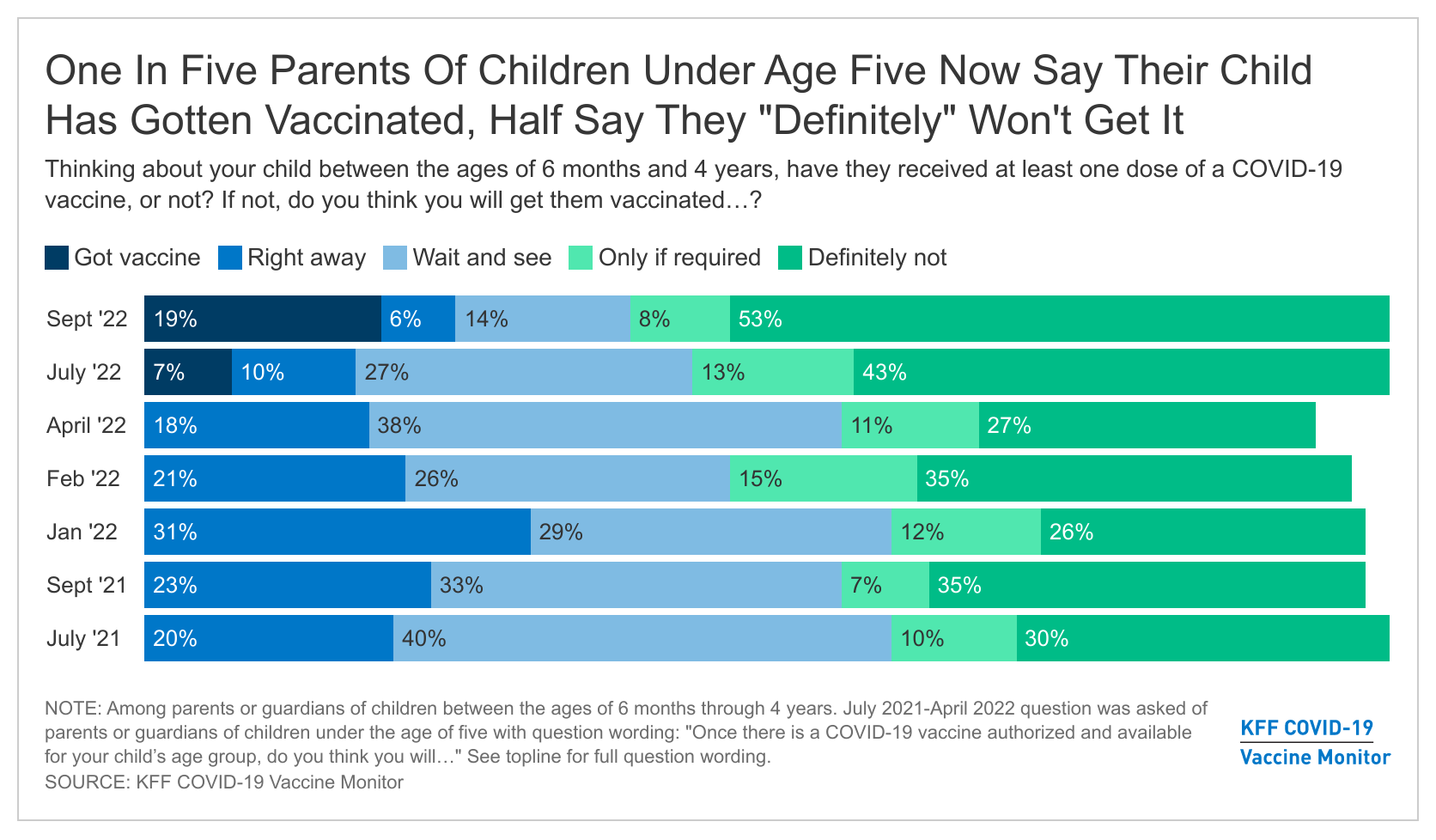

- About one in five (19%) parents of children ages 6 months through 4 years old say their child has gotten vaccinated for COVID-19, up from 7% in July. The September Monitor survey finds about half (53%) of parents of children in this age range say they will “definitely not” get their child vaccinated for COVID-19. Reported vaccine uptake among children ages 5-11 and teenagers ages 12-17 has slowed in recent months. Almost half of parents of kids ages 5-11 now report their child has gotten vaccinated (46%), as do 62% of parents of teens ages 12-17.

COVID-19 Vaccination Rates And New COVID-19 Boosters

Overall adult vaccination rates have been relatively steady over the past year. The latest COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that nearly eight in ten adults (77%) say they have gotten at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, including about half who say they are fully vaccinated and also received at least one booster dose (47%), about a quarter who have been fully vaccinated but have not gotten a booster (26%), and a small share who are partially vaccinated (3%). Twenty-three percent remain unvaccinated, the vast majority of whom say they will “definitely not” get the COVID-19 vaccine (88% of unvaccinated, or 21% of all adults). For the latest breakdown of self-reported vaccination rates by demographic group, see the Vaccine Monitor Dashboard.

In late August, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the use of new, updated COVID-19 vaccine boosters that target both the new omicron variants and the original strain of the virus. The bivalent boosters (one by Moderna and one by Pfizer) are now authorized for use by those ages 12 and older who have gotten an initial series of a COVID-19 vaccine, including those who have already received one or more boosters.

Awareness of the new boosters is modest, with about half of adults saying they have heard “a lot” (17%) or “some” (33%) about updated booster, 31% saying they have heard “a little,” and one in five saying they have heard “nothing at all” about the new booster doses.

Older adults and Democrats are somewhat more likely than their counterparts to say they have heard at least “some” about the new boosters, but fewer than a quarter across these groups report hearing “a lot” about the new shots.

The CDC has recommended that all adults get a bivalent COVID-19 booster at least two months after they complete their primary vaccine series.

Among the 73% of adults who received at least a full initial COVID-19 vaccine series, about half (49%) recognize that the CDC currently recommends the booster for people like them, while about one in ten (11%) say the new, updated booster is not recommended for people like them.

The CDC recommends the new booster for vaccinated adults of all ages, with a focus on vaccinating those ages 50 and older. Almost six in ten fully vaccinated adults ages 65 and older (57%) know the new booster is recommended for people like them, as do about half (49%) of those ages 50-64. Younger adults are less certain, with 19% of fully vaccinated adults under ages 30 saying they don’t believe the new booster has been recommended for their group and another 43% saying they are unsure.

Four in ten fully vaccinated adults say they are not sure if the CDC has recommended that people like them get the bivalent booster, including about half of fully vaccinated rural residents (54%), Hispanic adults (51%), and those without a college degree (49%) who say they are not sure.

One-Third Of All Adults Intend To Get the New Booster As Soon As Possible, Rising To Half Of Older Adults

About a third of adults say they have either received the updated bivalent COVID-19 booster dose (5%), which had been available for one to two weeks when the survey was in the field or say they plan to get the new booster as soon as possible (27%). About one in five say they want to “wait and see” before getting the new booster (18%), while 10% will get it “only if required” and 12% say they will “definitely not” get the updated booster dose. Around a quarter of adults are unvaccinated or only partially vaccinated, and therefore not eligible for the new bivalent booster dose.

As with the initial vaccinations, older adults appear to be among the earliest adopters of the new booster. Almost half (45%) of adults ages 65 and older say they’ve gotten the new booster or want to get it as soon as possible. These older adults are among the groups public health officials are focused on getting boosted sooner, as they are more susceptible to serious complications from COVID-19.

The partisan divide also mirrors early COVID-19 vaccine uptake, with six in ten Democrats (60%) saying they’ve already gotten the shot or will get it as soon as possible compared to one in eight Republicans (13%). Notably, 20% of Republicans say they will “definitely not” get the new COVID-19 booster dose, while a further 38% of Republicans are unvaccinated or only partially vaccinated and therefore not eligible for the new updated COVID-19 booster dose.

Vaccination Rates for Children

In July, the FDA granted emergency authorization for both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines for use in children ages 6 months through 4 years old. The latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor survey finds relatively slower initial uptake for this group than for older children for whom the COVID-19 vaccine was authorized last year.

About one in five (19%) parents of children ages 6 months through 4 years old now say their child has gotten vaccinated for COVID-19, up from 7% in July. Few remaining parents of children in this age range (6%) say they plan to vaccinate their children “right away,” while 14% say they want to “wait and see” and another 8% of parents of young children will get them vaccinated “only if required” for school or other activities.

The September Monitor survey finds about half (53%) of parents of children ages 6 months through 4 years old say they will “definitely not” get their child vaccinated for COVID-19. The share who say they will “definitely not” get their young child vaccinated for COVID-19 has increased from surveys taken earlier this year, when the vaccines were not yet available.

Reported vaccine uptake among children ages 5-11 has slowed slightly in recent months. Almost half of parents of kids ages 5-11 now report their child has gotten vaccinated (46%), continuing to tick up from earlier in the year. Just 2% of parents now say they will get their child vaccinated right away, and another 9% of parents of 5-11 year-olds still want to “wait and see.”

The share who say they will get their 5-11 year-old vaccinated “only if required” (8%) or will “definitely not” get them vaccinated (35%) has held steady over the past few months.

Parents’ intentions to vaccinate their older children have remained relatively steady since the start of the year. Almost six in ten parents of teenagers, ages 12-17, say their child has been vaccinated (62%), with very few parents who say they want to “wait and see” before deciding (2%). Around three in ten parents of 12-17 year-olds say they will definitely not get their child vaccinated (31%) while a further 5% say they will only do so if they are required.

Methodology

This KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor Poll was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted September 15-26, 2022, online and by telephone among a nationally representative sample of 1,534 U.S. adults including 599 women aged 18 to 49, conducted in English (1,475) and in Spanish (59). The sample includes 1,282 adults reached through the SSRS Opinion Panel[1] either online or over the phone (n=36 in Spanish). The SSRS Opinion Panel is a nationally representative probability-based panel where panel members are recruited randomly in one of two ways: (a) Through invitations mailed to respondents randomly sampled from an Address-Based Sample (ABS) provided by Marketing Systems Groups (MSG) through the U.S. Postal Service’s Computerized Delivery Sequence (CDS); (b) from a dual-frame random digit dial (RDD) sample provided by MSG. For the online panel component, invitations were sent to panel members by email followed by up to three reminder emails. 1,241 panel members completed the survey online and panel members who do not use the internet were reached by phone (41). In appreciation for their participation, web-panelists received a $10 incentive for participation in the form of an electronic gift card.

Another 252 (n=23 in Spanish) interviews were conducted from a random digit dial telephone sample of prepaid cell phone numbers obtained through MSG. Phone numbers used for the prepaid cell phone component were randomly generated from a cell phone sampling frame with disproportionate stratification aimed at reaching Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black respondents. Stratification was based on incidence of the race/ethnicity groups within each frame. Respondents in the phone samples received a $10 incentive.

The combined cell phone and panel samples were weighted to match the sample’s demographics to the national U.S. adult population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2021 Current Population Survey (CPS). Weighting parameters included gender, age, education, race/ethnicity, region, and household tenure. The sample was weighted to match patterns of civic engagement from the September 2017 Volunteering and Civic Life Supplement data from the CPS and to match frequency of internet use from the National Public Opinion Reference Survey (NPORS) for Pew Research Center. Finally, the sample was weighted to match patterns of political party identification based on a parameter derived from recent multi-mode benchmarking polls conducted by SSRS. The weights take into account differences in the probability of selection for each sample type (prepaid cell phone and panel). This includes adjustment for the sample design and geographic stratification of the cell phone sample, within household probability of selection, and the design of the panel-recruitment procedure.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample is plus or minus 3 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error and there may be other unmeasured error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total | 1,534 | ± 3 percentage points |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 864 | ± 4 percentage points |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 260 | ± 9 percentage points |

| Hispanic | 283 | ± 8 percentage points |

| Party identification | ||

| Democrat | 622 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Republican | 342 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Independent | 378 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Parents | ||

| Parent with a child ages 6 months through 4 years old | 179 | ± 10 percentage points |

| Parent with a child ages 5-11 | 251 | ± 8 percentage points |

| Parent with a child ages 12-17 | 235 | ± 9 percentage points |