Introduction

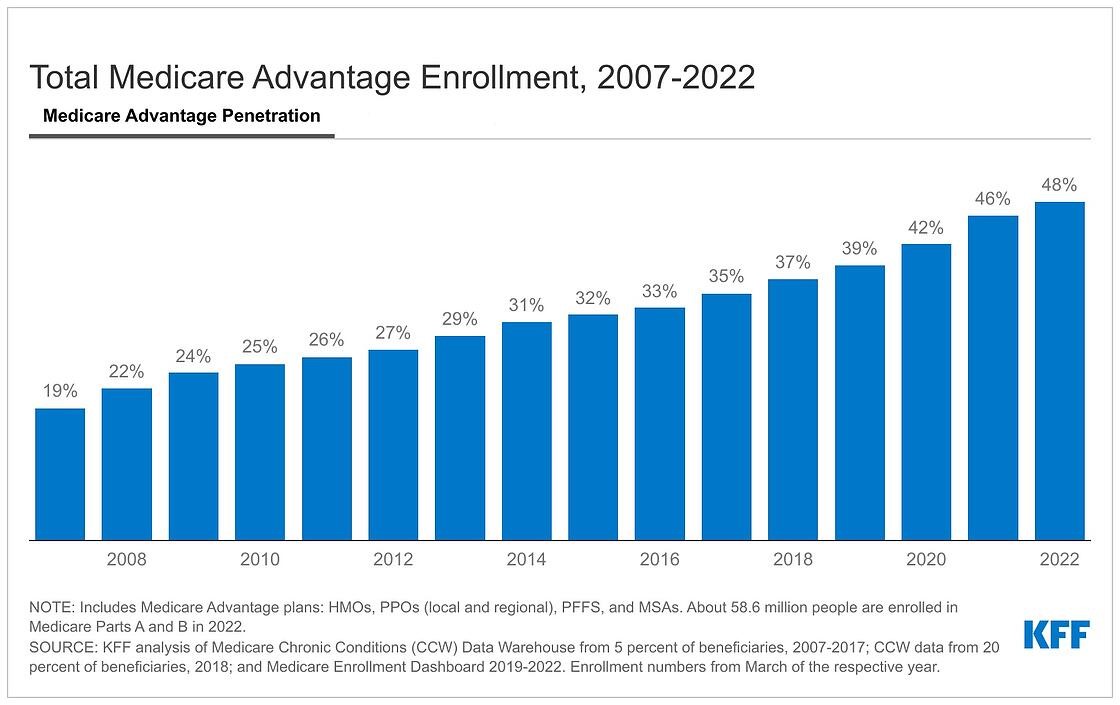

Over the last decade, Medicare Advantage enrollment has grown rapidly, rising from 25% of the eligible Medicare population in 2010 to nearly half of the Medicare population in 2022. The Medicare Advantage population has become increasingly diverse, with half of all Black Medicare beneficiaries and 56% of Hispanic beneficiaries enrolled in a Medicare Advantage plan, as of 2019, compared to just over a third of White beneficiaries (37%). Additionally, beneficiaries who are under age 65 with long-term disabilities and beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid account for a growing share of the Medicare Advantage population.

Medicare Advantage plans have several features that may attract enrollees, including an out-of-pocket limit for Medicare-covered services and additional benefits not available under traditional Medicare, such as dental, hearing, and vision benefits. These benefits are often available at little or no extra premium (other than the Part B premium). However, Medicare Advantage plans typically have more limited provider networks. Additionally, there has been growing concern about higher spending on behalf of Medicare Advantage enrollees relative to traditional Medicare beneficiaries. A KFF analysis estimated that federal spending on behalf of Medicare Advantage enrollees was $321 higher per person in 2019 than it would have been if enrollees had instead been covered by traditional Medicare, contributing an estimated $7 billion in additional spending in that year.

The growing role of Medicare Advantage and the relatively high spending on this program raise the question of how well private plans serve their enrollees compared to traditional Medicare. To answer this question, we reviewed 62 studies published between January 1, 2016 and May 1, 2022 that compare Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, building on a previous KFF review of research by examining the most recent evidence available on measures of beneficiary experience, affordability, service utilization, and quality.

The studies we reviewed varied widely in terms of methodology, data, and observation years (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Notably, relatively few studies looked specifically at beneficiaries from communities of color, beneficiaries living in rural areas, or beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Additionally, despite an increased focus on alternative payment models in Medicare, only two of the studies looked separately at traditional Medicare beneficiaries attributed to accountable care organizations (ACOs). All differences reported in this report are statistically significant (with p-value less than or equal to 0.05) unless noted otherwise. Additionally, studies attempted to account for differences in beneficiary characteristics such as health status and demographics in some fashion, unless noted otherwise. See Appendix Table 2 for more detailed descriptions of these studies, including data sources, methodology, and whether the analysis attempts to account for differences in beneficiary characteristicsBack to top.

Medicare Advantage vs. Traditional Medicare: Literature Review

We identified 62 studies published between January 1, 2016 and May 1, 2022 that used at least one year of data after 2010 and compared Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare on measures of beneficiary experience, affordability, utilization, or quality. We included studies published in peer-reviewed publications, studies conducted by research and policy organizations, and government reports. The vast majority of studies in our review (49 studies) used data sources that are nationally representative, while six studies used data for a subset of states, one study used administrative data from a single hospital, and six studies used claims or encounter data collected from a single health plan (e.g., Humana), a single health care delivery system (Banner Health), or from a set of hospitals (Appendix Table 2). Just two studies stratified findings for traditional Medicare by whether beneficiaries were attributed to an accountable care organization (ACO).

Ideally, this review would assess differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare using relatively recent data. However, just 12 of the 62 studies published since 2016 used data from the past five years, while the remaining 50 studies used data from between 2010 and 2017.

Beneficiary experience

We reviewed 16 studies that examined aspects of beneficiaries’ experiences with Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, including satisfaction with care (6 studies), access to care (7 studies), care coordination (3 studies), experience with prescription drugs (5 studies), and switching between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare (which may be interpreted as an indicator of satisfaction) (4 studies) (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Several of these studies overlapped in the measures examined.

Overall, Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported similar levels of satisfaction with care. With respect to access measures, Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to report having a usual source of care, while both groups reported similar experiences with wait times and finding a new provider. Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries were similarly satisfied with care coordination overall, but Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to report receiving information during care transitions and were somewhat more likely to report a better experience getting needed prescription drugs. Additionally, while switching between the two coverage types was relatively infrequent in either direction, it occurred more often among Medicare Advantage enrollees who opted to disenroll from Medicare Advantage and switch into traditional Medicare, particularly among higher-need beneficiaries.

Satisfaction with care

Five studies found no differences in measures of care satisfaction between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Overall, the vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries reported being satisfied with their care in both Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.1 One analysis using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, found no differences in satisfaction between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with five aspects of care, including doctor’s concern with overall health, information about medical condition, care by specialist, information obtained by phone, and quality of medical care.2 The analysis did not control for differences in beneficiary demographic, socioeconomic, or health characteristics (Appendix Table 2).

Three additional studies also used data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey to compare satisfaction among beneficiaries with diabetes,3 Alzheimer’s disease,4 or mental illness (defined as a presence of any mental disorder or depression)5 and found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in several care satisfaction measures, including satisfaction with quality of medical care and availability of care by specialists. However, the authors of the studies on diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease noted that sample sizes for these two groups may have been too small to detect differences.

A separate study that used data from the Health and Retirement Study found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share that reported being very satisfied with the quality of their care.6 This study examined high-need beneficiaries, defined as those with at least three chronic conditions and at least one limitation in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental ADLs, and non-high need beneficiaries.

We were unable to identify studies that compared satisfaction rates for Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries among other subgroups of the Medicare population, such as by race/ethnicity, age group, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, and rural status.

One study found that experience with care at the end-of-life was rated higher for traditional Medicare than Medicare Advantage. Friends and family reported lower quality end-of-life care for decedents in Medicare Advantage than decedents who had traditional Medicare, even after stratification by hospice enrollment.7 Though Medicare Advantage did not cover health care services for people in hospice at the time of the analysis, Medicare Advantage decedents who died in hospice were included because Medicare Advantage plans may play a major role in end-of-life care planning before hospice, guide enrollees to a specific hospice, or oversee other aspects of care.

Access to care

Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to report having a usual source care. The vast majority of Medicare beneficiaries in both Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare reported having a usual source of care.8 , 9 The share of Medicare Advantage enrollees who reported having a usual source of care was higher by between 0.9 and 4.0 percentage points depending on the study, year, and data.10 , 11 , 12 Additionally, one study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to report a primary care clinician as their regular source of care.13

Studies that looked at the subset of Medicare beneficiaries who were age 65 and older14 and studies that looked at the subset of Medicare beneficiaries with long-term disabilities between age 18 and 64 also found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to report a usual source of care than traditional Medicare beneficiaries in both age groups.15

However, in a study that looked separately at high-needs beneficiaries (those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and non-high-needs beneficiaries, there were no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries in the share reporting having a usual source of care.16

Among people of color (grouped together), a slightly larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported having a usual source of care (91% vs 88%) and a primary care clinician as the source of regular care (79% vs 73%).17 Due to data limitations, the authors of that one study combined Black, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian/Pacific Islander people into a single category.

Two studies examined the share of Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries that reported difficulty getting needed health care, with inconsistent findings. In a nationally-representative study, there were no statistically significant differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share of beneficiaries reporting difficulty getting needed health care.18 That study also found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share of beneficiaries reporting that they had a treatment plan for their condition, or that they always or often received an answer about a medical concern the same day they contacted their usual source of care. However, the study did not control for differences in beneficiary case-mix (Appendix Table 2).

Another study examined a subset of beneficiaries in New York, Florida, and California and found that the share of Medicare Advantage enrollees reporting difficulty getting needed care was approximately two percentage points lower than the share of traditional Medicare beneficiaries.19

There was mixed evidence on other measures of access between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to report having a health care professional they could easily contact in between doctor visits, but reported similar wait times as beneficiaries in traditional Medicare for outpatient and physician office visits.20 Additionally, there were no differences in the share of Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries reporting trouble finding a general doctor, being told that their health insurance was not accepted, and being told they would not be accepted as a new patient.21 A separate study also found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share of beneficiaries reporting difficulty finding a provider, for both the subset of beneficiaries with high-needs (those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and without high-needs. 22

A fourth study that looked at Medicare beneficiaries with cancer in their last year of life found that those in traditional Medicare were more likely than those in Medicare Advantage to report excellent experience getting care quickly and getting needed care.23

Care coordination

Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported similar experiences on measures of care coordination overall. Two studies compared measures of care coordination in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare and found no differences between beneficiaries in either group.24 , 25 Additionally, one of these studies found no differences in the share of beneficiaries reporting that their regular doctor always or often helps coordinate care with other providers.26

A larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported specific care management practices in one study. Compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries, a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees reported that their health care professional had discussed with them their main goals or priorities in caring for their condition (76% versus 60%, respectively) or had given them given them clear instructions about symptoms to monitor in caring for their condition after returning home from the hospital (97% versus 90%, respectively).27 The study did not control for differences in beneficiary demographic, socioeconomic, or health characteristics (Appendix Table 2).

That same study also compared measures of care coordination among beneficiaries with three or more chronic conditions or limitations in activities of daily living (defined in the study as “high need”) and beneficiaries with diabetes.28 Among these subgroups, there were no statistically significant differences between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share reporting that their regular doctor always or often helps coordinate care with other providers. However, consistent with the overall findings, among these subgroups a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported that their health care professional had discussed with them their main goals or priorities in caring for their condition.

Another study found that among the subgroups of beneficiaries with high-needs (those with three or more chronic conditions and an ADL or an instrumental ADL) and without high-needs, there were no differences between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share reporting that their preferences were usually or always taken into account.29

Experience with prescription drugs

Medicare Advantage enrollees reported better experiences getting needed prescription drugs than traditional Medicare beneficiaries overall, but among beneficiaries with specific conditions, findings were mixed. Five studies examined experiences with prescription drugs among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). In a study of Medicare beneficiaries in California, New York, and Florida, a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported that they were satisfied with their experience getting needed prescription drugs (91.4% in Medicare Advantage vs 87.3% in traditional Medicare).30 Another analysis found that compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries in stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs), enrollees in Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans (MA-PDs) reported greater ease obtaining medications (90.1% vs. 87.9%, respectively), less difficulty getting coverage information (81.2% vs. 78.2%, respectively) and less difficulty getting cost information (80.4% vs. 78.9%, respectively).31

A third study found that a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees (91%) than traditional Medicare beneficiaries (84%) reported having a health care professional review their medications in the past year.32 However, among beneficiaries with diabetes, mental health conditions, or cancer, this same study reported that differences between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare were not statistically significant. While the analysis compared the experiences of beneficiaries with certain health conditions, it did not further control for differences in beneficiary characteristics (Appendix Table 2).

A study that examined beneficiaries with a mental illness found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare on satisfaction with list of prescriptions covered.33

The fifth analysis found that among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer in their last year of life, those in traditional Medicare were more likely than those in Medicare Advantage to report excellent experience getting needed prescription drugs.34

Switching between Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare

Medicare beneficiaries can make a change in their coverage by switching from traditional Medicare to a Medicare Advantage plan (or vice versa) during the Medicare Open Enrollment period each year. Other beneficiaries, such as those dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid and beneficiaries in certain institutions, such as nursing homes, may switch coverage more frequently. Researchers use rates of disenrollment or switching as a proxy measure for satisfaction with Medicare coverage.

We identified four studies that examined switching in both directions (Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare and traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage) using at least one year of data since 2010. Of these four studies, two did not control for differences in beneficiary case-mix or health risk, including one study that presented descriptive statistics without statistical testing (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). These four studies found that overall, there were low rates of switching between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare; however, there were higher rates of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare among beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, beneficiaries of color, beneficiaries in rural areas, and following the onset of a functional impairment. Authors of these studies discussed several factors that could explain differences in switching among certain beneficiaries, including networks in some plans that beneficiaries with complex care needs may deem restrictive; however, studies did not determine the specific reasons beneficiaries switched their source of Medicare coverage.

Beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, particularly those with high health needs, and beneficiaries of color had relatively high levels of switching between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. One study examining beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid found that these beneficiaries switched between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare at a higher rate than non-dual-eligible beneficiaries, regardless of the direction of switching.35 These findings may in part be attributable to the fact that dually eligible beneficiaries are able to switch plans once per calendar quarter in the first three quarters of the year, in addition to the open enrollment period. In addition, high-need dual-eligible beneficiaries were more likely to disenroll from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare than dual-eligible beneficiaries who were not classified as high need. In comparison, a smaller share of high-need dual-eligible beneficiaries who were enrolled in traditional Medicare switched to Medicare Advantage than non-high need dual eligible beneficiaries.

Another study looked at beneficiaries’ enrollment decisions after the onset of a functional impairment and found that beneficiaries of color were more likely to switch sources of Medicare coverage than White beneficiaries regardless of whether they started with Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare.36 Specifically, beneficiaries of color accounted for 24% of the Medicare Advantage population in the study’s sample but 47% of Medicare Advantage enrollees who switched from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare. In comparison, beneficiaries of color accounted for 15% of the study’s traditional Medicare population and 21% of traditional Medicare beneficiaries who switched from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage. Authors of the study were unable to report switching patterns for individual racial and ethnic groups separately due to sample size and data reporting restrictions. Additionally, due to sample size limitations, the analysis was precluded from using multivariable regression models to examine factors that were independently associated with switching (Appendix Table 2). It is possible that higher rates of switching among beneficiaries of color may reflect the fact that a relatively large share of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, and therefore able to switch more frequently during the year.

A study of beneficiaries living in rural areas found that a larger share of rural beneficiaries switched from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare than switched from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage. One study found that among beneficiaries in rural areas, the rate of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare (10.7%) was higher than the rate of switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage (1.7%).37 Among beneficiaries in non-rural areas, the difference in switching rates between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare was narrower, but the rates were still higher among those switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare (4.6%) than those switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage (2.2%).

Few studies have examined patterns of switching among beneficiaries with complex health needs, with one study finding that after the onset of functional impairments, a larger share of beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage switched to traditional Medicare compared to the share of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare that switched to Medicare Advantage. One of the four studies described above found that following the onset of a functional impairment, beneficiaries ages 65 and older were more likely to switch from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare than from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage.38 Specifically, following the onset of a functional impairment, the rate of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare was 65.6 switches per 1,000 person-years, while the rate of switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage was 44.4 switches per 1,000 person-years. Due to sample size limitations, the analysis was precluded from using multivariable regression models to examine factors that were independently associated with switching (Appendix Table 2).

The fourth study presented descriptive statistics on switching by people with newly-diagnosed diseases or conditions but did not test whether observed differences were statistically significant.39 The authors found that overall, the rate of switching for this group from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage (4.1%) was higher than the rate of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare (2.2%). This pattern held for most newly-diagnosed diseases and conditions in the analysis, such as Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, hypertension, and cancer. However, among beneficiaries newly diagnosed with stroke, the rate of switching from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage (2.2%) was slightly lower than the rate of switching from Medicare Advantage to traditional Medicare (2.6%).

Affordability

We identified seven studies that compared affordability-related difficulties among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). These studies generally found that a somewhat larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries experienced a cost-related problem, mainly due to lower rates of cost-related problems among traditional Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental coverage. These studies found that traditional Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental coverage had the most affordability-related difficulties.

Medicare Advantage enrollees who are Black, under age 65 with disabilities, or in fair or poor health were more likely to report cost-related problems than their traditional Medicare counterparts. Few differences were found among beneficiaries with high-needs, a mental illness, or diabetes.

Traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported fewer cost-related problems than enrollees in Medicare Advantage, mainly driven by traditional Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental insurance. Two studies compared reports of cost-related problems between Medicare Advantage enrollees, traditional Medicare beneficiaries with supplemental insurance, and traditional Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental insurance. The first study examined the share of each group that reported trouble getting care due to cost, a delay in care due to cost, or problems paying medical bills, and found that the share reporting at least one cost-related problem was somewhat lower among beneficiaries in traditional Medicare overall (15%) and traditional Medicare with supplemental coverage (12%) than among Medicare Advantage enrollees (19%).40 The rate of cost-related problems was highest among traditional Medicare beneficiaries without supplemental coverage (30%). These findings held after controlling for income, race and ethnicity, Medicaid dual status, and health status.

Similarly, another analysis found that among adults ages 65 and older, the share reporting problems paying medical bills was higher among Medicare Advantage enrollees (8.3%) than among those in traditional Medicare with private supplemental coverage (5.6%).41 Again, a smaller share of both groups reported problems than among traditional Medicare beneficiaries with no supplemental coverage (12.4%). The analysis did not control for differences in beneficiary characteristics such as income. Two additional studies looked at ability to get needed health care or delays in care due to cost among Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries, without breaking out traditional Medicare beneficiaries with and without supplemental coverage. One of these analyses found that in 2009, Medicare Advantage enrollees were slightly more likely than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare to report delaying care for cost reasons; however, in 2017, differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare were not significant.42 The other study did not find statistically significant differences in the share of Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries reporting trouble getting health care because of high cost, though the analysis did not control for differences in beneficiary characteristics (Appendix Table 2).43

One study found that traditional Medicare beneficiaries report fewer cost-related problems than enrollees in Medicare Advantage when focusing on beneficiaries who are Black, under age 65 with disabilities, or in relatively poor health. One of the seven studies described above stratified results by race and ethnicity, age, and self-reported health status.44 The study found that among Black beneficiaries, beneficiaries under the age of 65, and beneficiaries in fair or poor self-assessed health, a smaller share of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare reported cost-related problems compared to enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans after adjusting for various beneficiary characteristics.

Three studies examining beneficiaries with high-needs or specific conditions found some differences in affordability-related measures between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. The first study looked at beneficiaries with high needs (i.e., those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and non-high needs beneficiaries, finding no statistically significant differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share of beneficiaries unable to afford care. 45

The second study examined measures of affordability among beneficiaries with a mental illness. This study found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in care dissatisfaction with out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs, delay in getting prescription drugs due to cost, and inability to get prescription drugs due to cost.46 However, enrollment in Medicare Advantage increased dissatisfaction with out-of-pocket expenses for medical care by 25.5 percentage points. That study further identified beneficiaries with depression specifically, finding that differences in dissatisfaction with out-of-pocket expenses for medical care among beneficiaries with mental illness were largely driven by beneficiaries with depression.

The third study examined beneficiaries with and without diabetes and found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share of beneficiaries with diabetes who were satisfied with out-of-pocket costs for medical care.47 However, Medicare Advantage enrollees without diabetes were slightly less likely to report satisfaction with out-of-pocket costs for medical care than traditional Medicare beneficiaries without diabetes.

Utilization

We reviewed 34 studies that compared the use of health care services between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries, including preventive services (7 studies), hospital care (15 studies), post-acute care and home health (18 studies), prescription drugs (5 studies), and other services (8 studies) (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Several of these studies overlapped in the measures examined. The analyses consistently found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had higher utilization of preventive services and lower utilization of post-acute care and home health services. Findings related to the use of hospital care, prescription drugs, and other services were mixed, with the variation likely due in part to differences in how outcome measures were defined, methodology and data. Just two studies analyzed utilization of health care services among demographic subgroups of the Medicare population, finding that among beneficiaries of color and beneficiaries under the age of 65, utilization of preventive services was greater for Medicare Advantage enrollees, consistent with the overall pattern of preventive services utilization.

Utilization of preventive services

Seven studies compared receipt of preventive care services among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). These studies examined vaccination rates for flu, pneumonia, and shingles and the receipt of several preventive screenings, finding that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to receive these preventive services, overall and among beneficiaries of color and beneficiaries under age 65.

Larger shares of Medicare Advantage enrollees reported having an annual wellness visit or routine checkup than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Two studies compared rates of annual wellness visits or routine checkups between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Both found a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees reported a routine checkup48 or annual wellness visit, with Medicare Advantage enrollees also more likely to report that the annual wellness visit included a cognitive assessment.49 The authors of the study that found higher rates of cognitive assessments in annual wellness visits among Medicare Advantage enrollees acknowledged that drawing on data from an online panel may not capture people with severe cognitive impairments.50

Medicare Advantage enrollees had higher rates of vaccinations than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Three studies examined overall flu vaccination rates and found a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries received their annual flu vaccine.51 , 52 , 53 The difference in the shares of Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries receiving the flu vaccine ranged from 2.2% to 3.5%.54 , 55 One of these studies also compared receipt of pneumonia vaccines and found higher rates in Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare, with a difference of 2.0% between the two coverage types.56

An analysis that focused more narrowly on patients with heart failure found no statistically significant differences in receipt of flu or pneumococcal vaccinations between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.57

In a separate analysis looking at shingles vaccinations, a larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees in prescription drug plans (MA-PDs) did not fill prescribed shingles vaccines (8.9%) compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries in stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs) (6.4%).58 The analysis was limited to beneficiaries ages 65 and older and did not specify how it accounted for any differences in receiving the shingles vaccine before enrolling in Medicare.

Despite the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Medicare beneficiaries, we were unable to identify studies meeting our inclusion criteria that examined COVID-19 vaccination rates by Medicare coverage group as of May 1, 2022.

Medicare Advantage enrollees reported higher rates of several preventive screening services. A larger share of Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries reported colorectal and breast cancer screenings and blood pressure screening.59 , 60 , 61 For instance, the difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in the share receiving colorectal cancer screening was 4.4 percentage points in one of these studies.62 One study also found higher rates of cholesterol management among Medicare Advantage (95%) enrollees compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries (87%),63 while another found no differences in this measure.64

Utilization of preventive service by race and ethnicity mirrored overall differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Patterns of flu and pneumonia vaccination were similar in a study that examined White beneficiaries; Black, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian and Pacific Islander beneficiaries (examined as a single group); and Black beneficiaries (examined separately). In this study, a higher share of beneficiaries of color in Medicare Advantage (67.3%) than in traditional Medicare (63.0%) reported receiving the flu vaccine.65 Similarly, a larger share of beneficiaries of color in Medicare Advantage (70.7%) than in traditional Medicare (64.6%) reported receiving a pneumonia vaccine. The study also presented results for Black beneficiaries separately from other groups, finding a similar pattern. However, the authors acknowledged that due to sample size limitations, they were unable to present disaggregated data for Hispanic, Native American, or Asian/Pacific Islander beneficiaries.

Among beneficiaries under the age of 65, utilization of preventive services was greater for Medicare Advantage enrollees, based on evidence from one study. Only one study examined the use of preventive services for people under 65 with long-term disabilities. Consistent with the overall patterns of preventive services utilization, the study found that among beneficiaries under the age of 65, Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to report receiving cholesterol and colon cancer screenings and flu vaccinations.66 We were unable to identify studies that analyzed preventive services utilization among beneficiaries dually eligible for Medicaid or beneficiaries in rural areas.

Hospital utilization

Fifteen studies compared measures of hospital utilization between Medicare Advantage enrollees and beneficiaries in traditional Medicare (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2), including the share of beneficiaries with at least one hospital stay (4 studies), the number of hospitals stays (4 studies), the average length of stay (3 studies), the total number of hospital days (2 studies), and hospitalizations near the end of life (3 studies) (some studies included multiple measures). Findings were mixed and varied based on the particular measure of utilization.

Studies examining the share of beneficiaries with at least one hospital stay had mixed findings, with two studies finding no difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare and two studies finding lower rates in Medicare Advantage. Two studies found no difference in the share of Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with at least one hospital stay.67 , 68 One of these studies did not control for differences in beneficiary demographic, socioeconomic, or health characteristics (Appendix Table 2).69 A separate study found that among high-needs beneficiaries (those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and non-high-needs beneficiaries, a smaller share of Medicare Advantage enrollees reported at least one hospital stay than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.70 Another study examined a single health delivery system, Banner Health, which partnered with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Arizona to provide a Medicare Advantage plan and also operated an Accountable Care Organization (ACO) in one county in Arizona. This study found that the Medicare Advantage enrollees had lower hospitalization rates compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries, both those who were attributed to the Banner ACO and the non- Banner, non-ACO beneficiaries.71

The number of hospital stays was lower in Medicare Advantage plans than in traditional Medicare for some groups of beneficiaries. Four studies found fewer hospital stays among Medicare Advantage enrollees compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries for at least some groups of beneficiaries. One study examined differences in inpatient hospital admissions for Medicare beneficiaries with and without Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD), finding slightly fewer hospitalizations among Medicare Advantage enrollees in both groups compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries.72 Specifically, among beneficiaries with ADRD, those in Medicare Advantage had 0.3 inpatient hospital admissions a year compared to 0.47 for those in traditional Medicare. The study used an instrumental variable design in an effort to address concerns about adverse selection into Medicare Advantage by healthier beneficiaries and controlled for other observable beneficiary characteristics (Appendix Table 2).

A second study examined changes in hospital use following transition from commercial insurance (prior to Medicare enrollment) to Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare with supplemental insurance (through Aetna) and found that enrollment in Medicare Advantage was associated with a larger reduction in the number of inpatient stays.73 This suggests that the use of hospital services is lower in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare. The study only followed beneficiaries for a single year after enrollment in Medicare and used data from a single insurer, Aetna, so findings may not be generalizable to the broader Medicare population, though the strong quasi-experimental design of the analysis is useful in isolating the effects of payer type for the group studied.

A third study looked at hospital admissions for beneficiaries with and without diabetes. The study found that among people with diabetes, Medicare Advantage enrollees had 0.1 fewer inpatient hospital stays per year on average than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.74 In the same study there were no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries in number of inpatient hospital stays for people without diabetes.

The fourth study found that among both high-needs beneficiaries (those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and non-high-needs beneficiaries, Medicare Advantage enrollees had fewer hospital stays than traditional Medicare beneficiaries, and the difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries was larger among high-needs beneficiaries than non-high needs beneficiaries (2.1 fewer inpatient stays versus 0.6 stays, respectively).75

An additional study examined inpatient hospital admissions among beneficiaries with a mental illness, finding no differences in number of inpatient hospital admissions between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. 76

Differences in the length of inpatient hospital stays between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries varied by type of admission. One study, based on a subset of beneficiaries in 28 states, found comparable lengths of stay for medical admissions, the most frequent type of admission. Medicare Advantage enrollees had shorter lengths of stay for mental health and longer lengths of stay for injury and surgical admissions.77 At the time of the analysis, the 28 states included in the sample accounted for 75 percent of all Medicare Advantage enrollees.

A second analysis, based on a subset of 18 states, presented descriptive statistics for the 20 most common types of admissions. With the exception of admissions for respiratory failure, where the average length of stay was shorter among Medicare Advantage enrollees (7.2 days) than traditional Medicare beneficiaries (8.2 days), the average lengths of stay for the remaining 19 admissions were similar between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries (a difference of less than 0.3 days on average), though statistical tests were not included in the report.78

A third study examined patients who underwent total hip and knee arthroplasty using claims data from a single insurer. The analysis found no difference in the length of stay for Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries but did not include adjustments for differences in beneficiary characteristics.79

The number of total hospital days did not differ between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Two studies included the number of hospital days per 1,000 beneficiaries, a measure that combines the number of admissions and length of stay. Neither study found a difference between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare after adjusting for beneficiary characteristics.80 , 81

Hospitalizations at the end-of-life were somewhat more common in traditional Medicare than in Medicare Advantage. One study calculated descriptive statistics for the site of death for Medicare beneficiaries and found that a smaller share of Medicare Advantage decedents were hospitalized during the last 30 and 90 days of their lives compared to decedents who were in traditional Medicare.82 Another study looked specifically at people with dementia and found that a smaller share of decedents who had Medicare Advantage were hospitalized in the last 30 days of life compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries, including those attributed to an Accountable Care Organization (ACO).83 A third study found no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare in hospital admissions in the last 30 days of life. 84

We were unable to identify studies that examined any measures of hospital utilization between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare that stratified by different demographic subgroups, such as by age group, dual eligibility, and race/ethnicity.

Post-acute And Home Health care utilization

Eighteen studies examined utilization of home health care and post-acute care services in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), long-stay nursing homes, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs) (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Ten of these studies evaluated utilization of post-acute care services in SNFs and other nursing homes, or IRFs, with most finding fewer days of care or shorter length of stays among Medicare Advantage enrollees compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Eleven studies included an examination of the use of home health care, with a majority finding somewhat lower use among Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Several studies overlapped in the type of post-acute care setting examined.

Medicare Advantage enrollees used fewer skilled nursing facility and inpatient rehabilitation services than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Ten studies examined post-acute care received in institutional settings (e.g., nursing homes, SNFs, and IRFs) and seven of these studies found lower utilization among Medicare Advantage enrollees compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries. These studies mostly examined discharges following hospitalizations for specific sets of conditions and looked at the likelihood of being admitted to a SNF or IRF, as well the average length of stay.

Four studies compared SNF use overall. The first found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had substantially fewer days of SNF care (2,337 days per 1,000 beneficiary-years) than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare (2,902 days per 1,000 beneficiary-years)—a difference of 565 days per 1,000 beneficiary-years, with greater geographic variation in the number of SNF days among enrollees in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare.85 The analysis controlled for demographic characteristics, as well as the number of limitations in activities of daily living and differences in cognitive function, but according to the authors, data limitations precluded a more robust adjustment for beneficiary health status (Appendix Table 1).

However, two studies that stratified beneficiaries by health needs found no differences in the use of SNFs between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries, for both the subsets of beneficiaries with or without Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD)86 or the subsets of beneficiaries with or without high needs (i.e., three or more chronic conditions and limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental ADLs).87

A fourth study compared SNF use by enrollees in a Medicare Advantage plan operated by Banner Health and Blue Cross Blue Shield, traditional Medicare beneficiaries attributed to an ACO operated by Banner Health since 2012, and traditional Medicare beneficiaries in the same county (Maricopa, Arizona) not attributed to the ACO. The study found that in 2012 and 2013, Medicare Advantage enrollees had fewer days of care in a SNF than traditional Medicare beneficiaries, including both Banner ACO beneficiaries and non-ACO beneficiaries; however, in 2014, differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries who were not attributed to the Banner ACO were not statistically significant.88 The study also examined SNF use in the two years preceding ACOs (2010-2011) by comparing Medicare Advantage enrollees, the cohort of traditional Medicare beneficiaries who were eventually assigned to an ACO in 2012, and the cohort of traditional Medicare beneficiaries who were not attributed to an ACO in 2012. The authors found fewer days of care among Medicare Advantage enrollees than the traditional Medicare groups.

We identified three studies that examined the use of post-acute care following hospitalizations for high-volume conditions, including joint replacement, stroke, and heart failure, and these studies found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to be discharged to a SNF or IRF.89 , 90 , 91 Once admitted to an IRF, Medicare Advantage enrollees received fewer days of care in these facilities.92 Shorter lengths of stays in SNFs and fewer minutes of rehabilitation care were also found following hospitalization for hip fracture for Medicare Advantage enrollees compared to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare.93

One analysis of patients undergoing total hip and knee arthroplasty at a single institution found no difference in the likelihood of being discharged to a SNF following the procedure between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries.94

Studies examining outcome measures for users of skilled nursing facilities found lower hospital readmission rates among Medicare advantage enrollees, but inconsistent findings on other outcome measures. Four studies, including one that followed a subset of beneficiaries hospitalized for joint replacement, stroke, and heart failure, examined outcome measures among users of skilled nursing facilities. These studies found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had lower hospital readmission rates and higher rates of return to the community and did not observe poorer outcomes (e.g., changes in functional status) relative to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare.95 , 96 , 97 However, one of the four studies found that among short-stay (i.e., SNF) residents, Medicare Advantage enrollees had lower rates of new or worsening pressure ulcers but higher rates of moderate to severe pain than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.98 In addition, that same study found that among long-stay residents (i.e., people with nursing home stays that extended beyond 100 days), Medicare Advantage enrollees had higher rates of urinary incontinence than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.

Most studies found utilization of home health was lower among Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Eleven studies examined utilization of home health care in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Eight of these studies found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had lower utilization of home health care services and three studies found no differences between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, either overall,99 or among subsets of beneficiaries with and without diabetes100 or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD).101

Six of the eight studies that found lower utilization of home health services among Medicare Advantage enrollees included an examination of the share of patients starting home health following discharge from the hospital.102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 These studies found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely to have a home health visit, and the findings were consistent across studies with various methodological approaches and strategies for addressing differences in beneficiary health status (see Appendix Table 1 and Appendix Table 2 for more detail). The share of enrollees receiving home health services ranged from 2.4% to 6.0% lower in Medicare Advantage compared to traditional Medicare. Additionally, while use of home health was consistently lower in Medicare Advantage, one study that examined trends found that the rates of home health use appeared to be converging over time.108

The seventh study compared high-needs beneficiaries (those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and non-high-needs beneficiaries found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to use home health care among both high-needs and non-high needs beneficiaries; however, the magnitude of the differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries was larger among high-needs beneficiaries (5.5 percentage point difference) than non-high needs beneficiaries (1.5 percentage point difference).109

The eighth study looked specifically at home health use among patients with cancer, finding that Medicare Advantage enrollees had lower rates of home health use and shorter lengths of home health care than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.110 While the study presented unadjusted differences that did not account for differences in beneficiary characteristics (Appendix Table 2), the results were consistent with overall findings from other studies that examined utilization of home health services.

Four of these eight studies also examined the duration of home health services and consistently found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had fewer days of home health use than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.111 , 112 , 113 , 114 Traditional Medicare beneficiaries had between 7.1 and 19.3 more days of home health days than Medicare Advantage enrollees, depending on the study.

Studies examining outcome measures for users of home health services found lower hospitalization rates among Medicare Advantage enrollees, but inconsistent findings on other outcome measures. Three studies examined whether home health users had different rates of hospitalization in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, finding lower rates of hospitalization among Medicare Advantage enrollees. Two of these studies, however, have notable limitations that may have confounded the findings. The first study controlled for measures like functional status, but not health status because this information was not available in the data for Medicare Advantage enrollees (Appendix Table 2).115 The second study did not account for the duration of home health and because traditional Medicare beneficiaries had longer home health episodes, they had more opportunities to be admitted to the hospital while receiving home health services.116 Additionally, the third used Medicare Advantage data from a single insurer which covered about 20% of the Medicare Advantage population at the time of the study, potentially limiting generalizability to the broader Medicare Advantage population.117

In addition, one of the studies looked at additional outcome measures among home health users. This study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees fared better with respect to dyspnea (trouble breathing), while traditional Medicare beneficiaries fared better with respect to improvements in pain.118

None of the studies that examined use of post-acute care among Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries included findings by race and ethnicity or other demographic subgroups (Appendix Table 1). Of the 18 studies in our review that examined receipt of post-acute care services in institutionalized (SNF, nursing home, and IRF) settings and home health, we were unable to identify any studies that stratified utilization estimates by both coverage type and demographic subgroups such as race and ethnicity, age group, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, and rural status, though some examined beneficiaries by condition.

Utilization of other services and prescription drugs

Ten studies examined utilization of other services, including outpatient and physician visits (6 studies), emergency department visits (2 studies), and prescription drugs (5 studies) (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Three studies overlapped in measures examined. These studies had mixed findings depending on the measure used.

Evidence on differences in outpatient and physician visits between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries was mixed. One study compared the number of primary care visits per person, defined as visits to providers in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatric medicine, and general practice specialties. The study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had more primary care visits per person than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.119

A second study examined changes in physician visits following transition from commercial insurance to either a Medicare Advantage plan (Aetna) or traditional Medicare with an Aetna supplemental insurance (i.e., Medigap) plan, finding that enrollment in Medicare Advantage was not associated with a statistically significant change in number of physician visits compared to traditional Medicare.120 This suggests that use of physician services is similar between Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries in the year following initial enrollment in Medicare.

Three studies examined utilization of medical practitioner visits, procedures, services, and supplied items among beneficiaries with and without diabetes or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) and beneficiaries with any mental illness, finding that Medicare Advantage enrollees had lower utilization of these services than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.121 , 122 , 123 Among those with diabetes, Medicare Advantage enrollees had 22.4 fewer of these services than traditional Medicare beneficiaries; among those without diabetes, Medicare Advantage enrollees had 12.5 fewer of these services than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Similarly, Medicare Advantage enrollees with ADRD had 22.3 fewer of these services than traditional Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD, and Medicare Advantage enrollees without ADRD had 15.0 fewer of these services compared to similar traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Among beneficiaries with any mental illness, Medicare Advantage enrollees had 36.48 fewer of these services than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. The studies on diabetes and ADRD excluded beneficiaries under the age of 65 and all three studies excluded beneficiaries whose original Medicare eligibility was attributable to end-stage renal disease.

A sixth study examined the number of physician visits and the share of beneficiaries with any physician visits among beneficiaries with high-needs (i.e., those with three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in activities of daily living (ADLs) or instrumental ADLs) and those without high-needs. That study found that among high-needs beneficiaries, Medicare Advantage enrollees had a 2.5 percentage point lower probability of having any physician visits; however, differences in the number of physician visits were not statistically significant.124 The study looked separately at those without high-needs, finding no difference in the share of beneficiaries with any physician visits, but a 1.8 percentage point reduction in number of physician visits among Medicare Advantage enrollees than traditional Medicare beneficiaries.

One of the six studies described above also examined outpatient hospital visits among beneficiaries with a mental illness, finding that Medicare Advantage enrollment was associated with 6.73 fewer outpatient hospital visits relative to traditional Medicare.125

Only two studies examined use of emergency department visits among Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries, yielding mixed results. We identified just two studies that analyzed differences in emergency department visits. One study found similar shares of Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older with an emergency department visit (34% for both groups).126 The study did not control for differences in beneficiary characteristics (Appendix Table 2). The second study examined a single hospital-based delivery system (Banner Health) that partnered with Blue Cross Blue Shield to offer a Medicare Advantage plan and beginning in 2012, participated in the Pioneer ACO program. This study found that in 2013 and 2014, the Medicare Advantage enrollees had higher emergency department visit rates than traditional Medicare attributed to the Banner-ACO and traditional Medicare beneficiaries not attributed to an ACO.127

Utilization of drugs administered by physicians and other health care providers (i.e., drugs that are covered under Medicare Part B that are typically used to treat cancer and other serious conditions) was similar between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, though Medicare Advantage was associated with more efficient use. One study found that upon transitioning from commercial insurance to an Aetna Medicare Advantage or traditional Medicare with an Aetna Medigap policy, there were no differences in the number of injectable drug procedures between the two groups.128 A second study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to receive low-cost Part B drugs in four clinical scenarios where similar or equally effective drugs exist, suggesting that Medicare Advantage coverage may be associated with more efficient prescribing of Part B drugs.129

Studies comparing differences in prescription drug utilization among Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries found inconsistent evidence. Five studies examined differences in utilization of prescription drugs among beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.

Three studies found no statistically significant differences in use of prescription drugs among beneficiaries with a mental illness, diabetes, or Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) in Medicare Advantage plans or traditional Medicare,130 , 131 , 132 but among beneficiaries without diabetes or ADRD, Medicare Advantage enrollees filled 27.6 and 19.4 more prescriptions than traditional Medicare beneficiaries, respectively. These studies did not specify the type of prescription drug purchases, including whether the drugs were brand or generic drugs.

Another study examined prescribing and utilization patterns related to opioids finding Medicare Advantage Prescription Drug (MA-PD) enrollees were less likely to fill a prescription for an opioid compared to traditional Medicare beneficiaries in stand-alone prescription drug plans (PDPs).133 The analysis accounted for beneficiary age, gender, and race, as well as characteristics of the county and local health care market but did not control for beneficiary-level health risk (Appendix Table 2).

The fifth study found no statistically significant differences in prescription drug use among Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with high-needs (i.e., three or more chronic conditions and a limitation in ADLs or instrumental ADLs) and among non-high needs beneficiaries.134

None of the studies that examined any measures of prescription drug or other service utilization stratified results by different demographic groups. Of the ten studies that examined utilization of outpatient and physician visits, emergency department visits, prescription drugs, and Part B drugs, none presented estimates by both Medicare coverage types and demographic subgroups such as race and ethnicity, age group, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility, and rural status.

Quality

We reviewed 27 studies that compared Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare on aspects of quality, including hospital readmission rates (12 studies), potentially avoidable hospitalizations (2 studies), quality rating of facilities (6 studies), disease management (7 studies), and use of low-value care (1 study), including one study that overlapped in measures examined (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Overall, neither Medicare Advantage nor traditional Medicare consistently performed better across all measures

Hospital readmissions

Twelve studies in our review compared hospital readmission rates between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). Seven of these studies generally found lower rates in Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare. Four studies that were more limited in scope found similar rates of readmission between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage and one study examining three conditions (acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pneumonia) included in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) found higher readmission rates among Medicare Advantage enrollees relative to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. Additionally, while Black beneficiaries had higher readmission rates than White beneficiaries in both Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare, there was a wider difference between Black and White patients in Medicare Advantage plans.

Readmission rates were generally lower in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare. Of the seven studies that found lower readmission rates among Medicare Advantage enrollees, 135 , 136 , 137 , 138 , 139 , 140 , 141 two studies focused on patients discharged to skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) after their initial hospitalization142 , 143 and two studies followed patients hospitalized for a subset of chronic conditions.144 , 145 One analysis focused on beneficiaries ages 65 and over who were hospitalized in one of 66 hospitals in a single state (WI), finding that readmission rates were lower among Medicare Advantage enrollees than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare within the same hospital for 62 out of 66 hospitals.146 Two studies examined readmission rates among beneficiaries in a subset of states that covered less than a third of the Medicare Advantage population, so findings may not be generalizable to the broader Medicare population.147 , 148

Four studies found similar rates of hospital readmissions between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare,149 , 150 , 151 , 152 though only one of these studies included a sample that was relatively broad. The study found no differences for readmissions for five conditions (acute myocardial infarction, pneumonia, heart failure, stroke and hip or knee replacement), with slightly lower readmissions for one condition, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, among Medicare Advantage enrollees (17.8%) than traditional Medicare beneficiaries (18.7%).153 The three other studies that found no difference in hospital readmission rates were based on a single hospital,154 claims from one insurer for hip or knee replacements,155 or six surgical procedures in a single state.156

One study that was national in scope found that Medicare Advantage enrollees had higher risk-adjusted readmission rates compared to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare.157 The analysis looked specifically at patients with acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and pneumonia. The authors found that the pattern of higher readmission rates among Medicare Advantage enrollees held when comparing beneficiaries admitted to the same hospital.

Black beneficiaries were more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than White beneficiaries in both Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare. Two studies examined readmission rates between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare stratified by race. The first focused on patients who were initially discharged to a skilled nursing facility.158 The second was based on a sample of patients undergoing at least one of six surgical procedures in hospitals in the state of New York.159 In both studies, Black beneficiaries had higher rates of 30-day hospital readmissions than White beneficiaries in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. However, the studies had inconsistent findings with respect to whether the disparity was greater in traditional Medicare or Medicare Advantage: in the study of patients initially discharged to a skilled nursing facility, the differences between Black and White beneficiaries were similar for both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage,160 but in the study of patients undergoing surgical procedures in New York,161 Black traditional Medicare beneficiaries were 33 percent more likely than White traditional Medicare beneficiaries to be readmitted, while Black Medicare Advantage enrollees were 64 percent more likely than White Medicare Advantage enrollees to be readmitted. While these studies examined disparities between White and Black beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, they did not separately compare differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare within each individual racial group.

We were unable to identify additional studies that stratified readmission estimates by other demographic subgroups such as by Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility and rural status.

Potentially avoidable hospitalizations

Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC) are considered potentially avoidable if appropriate care has been provided in a primary care setting. The rate of hospitalizations for ACSCs are therefore used as an indicator for quality. Two studies examined the rate of these potentially avoidable hospitalizations among Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries. However, only one of these studies accounted for differences in the characteristics of Medicare Advantage enrollees and traditional Medicare beneficiaries. After controlling for beneficiary characteristics, Black beneficiaries had higher rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare.

Traditional Medicare beneficiaries had higher rates of hospitalization for ACSCs in a study that did not control for age or health status differences. One study found that traditional Medicare beneficiaries were hospitalized more often than Medicare Advantage enrollees for ACSCs.162 The study did not evaluate statistical significance or adjust beneficiary characteristics (Appendix Table 2).

Black Medicare Advantage enrollees had higher rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations for ACSCs than Black traditional Medicare beneficiaries. One study compared hospitalizations for ACSCs between Black and White beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.163 After controlling for differences in demographic characteristics and chronic conditions, this study found that Black Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to be hospitalized for ACSCs (221.2 ACSCs per 10,000 beneficiaries) than Black traditional Medicare beneficiaries (209.3 ACSCs per 10,000 beneficiaries), but there were no differences between White Medicare Advantage enrollees and White traditional Medicare beneficiaries.

Disparities between Black and White beneficiaries in rates of potentially avoidable hospitalizations for ACSCs were larger in Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare. In addition to finding differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare for Black, but not White beneficiaries, this same study found that the differences between Black and White beneficiaries were larger in Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare (59.0 ACSCs per 10,000 beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage compared to 45.6 ACSCs per 10,000 beneficiaries in traditional Medicare). Further, differences between Black and White Medicare Advantage enrollees were present in nearly all hospital markets, while differences between Black and White beneficiaries in traditional Medicare were observed in just over half of the geographic areas.164

Quality of facilities

Six studies compared the quality of facilities used by beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). These studies generally found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to receive care from the highest or lowest rated hospitals overall, or highest-rated hospitals for cancer care, skilled nursing facilities, and home health agencies.

Two studies found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to receive care from higher-rated hospitals. Two studies examined the quality of admitting hospitals specifically. One study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to be admitted to average-quality hospitals rather than either high- or low-quality hospitals for non-emergent conditions; differences for emergency conditions were not significant.165 The study also examined the quality of hospitals for rural beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, finding no difference between the two coverage types. The second study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare to use a top-ranked cancer hospital for five cancer-related surgical procedures.166

Two studies found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely to receive care from the highest-quality home health agencies and skilled nursing facilities. Two studies examined the quality ratings of home health agencies and found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to receive care from high-quality home health providers.167 , 168 Another study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to enter nursing homes with lower quality ratings and higher rehospitalization rates compared to beneficiaries in traditional Medicare, after controlling for clinical conditions and facility-level characteristics.169

The sixth study examined 18 facility-level quality measures in long-stay nursing homes (i.e., nursing homes) and short-stay nursing homes (i.e., SNFs), finding no differences between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare for ten of the measures. However, the remaining eight measures had inconsistent findings: while Medicare Advantage enrollees in SNFs and long-stay nursing homes had lower risk of antipsychotic drug use, traditional Medicare beneficiaries in SNFs and long-stay nursing homes had lower risk of moderate to severe pain and urinary incontinence, respectively.170

Disease management

Seven studies examined measures of disease management or quality of care for specific diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease (Appendix Table 1, Appendix Table 2). These three disease areas are of interest because of their prevalence or cost. Nearly a third (32%) of all Medicare beneficiaries have heart disease and about a third (34%) have diabetes. While people with end-stage renal disease accounted for about 1% of the total Medicare population in 2019, they represent a disproportionate share of Medicare spending. These studies had mixed findings depending on the condition and quality measure.

Medicare Advantage enrollees with heart disease were more likely than traditional Medicare beneficiaries to receive guideline-recommended therapies in ambulatory settings, but not during an inpatient admission. One study, using data from patients who were hospitalized for heart failure, found no statistically significant differences between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage across most quality measures, such as receipt of guideline-recommended therapies.171 A second analysis of patients with coronary heart disease in the ambulatory setting found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely to receive guideline-recommended secondary prevention treatment (i.e., statins), but there were no significant differences in intermediate outcomes (e.g., systolic and diastolic blood pressure) between beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare.172

The authors of these two studies note that differences in findings for ambulatory versus inpatient settings could be partially attributed to the way Medicare Advantage plans negotiate contracts with providers in these two settings. Specifically, because ambulatory clinicians negotiate contracts directly with Medicare Advantage plans, which may include quality benchmarks, clinicians in this setting are incentivized to provide better quality of care. While similar quality contracts exist in the inpatient hospital setting, inpatient physicians may be unaware of the specifics of the contract, limiting plans’ influence in incentivizing inpatient physicians’ practice.

Four studies comparing quality and experiences with care among beneficiaries with diabetes in Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare had mixed findings. One analysis of adults ages 65 and older with diabetes found a larger share of Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare beneficiaries with diabetes “had medication use” (72.7% versus 62.5%) but Medicare Advantage enrollees were less likely to have a blood sugar test (70.3% versus 79.7%) or a test for average blood sugar level over the past three months (HbA1C) (86.6% versus 93.9%).173 The study found no significant differences on five other process measures of diabetes care, including whether blood sugar was well controlled, insulin use, blood pressure check at home, comprehensive foot exam, and checks for sores on feet. That study also found no differences between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage in care satisfaction, general health status, or change in health status among diabetic beneficiaries.

A second study found that Medicare Advantage enrollees were more likely than beneficiaries in traditional Medicare to be prescribed guideline-recommended therapy for diabetes.174 The study also found that traditional Medicare beneficiaries were more likely to be treated with medications from newer drug classes, which could represent higher quality of care but also more costly treatment (as these medications do not yet have generic alternatives). The scope of the study did not include process measures of diabetes care, such as whether blood sugar was well controlled.

A third study found that among beneficiaries in three states (CA, FL, NY), Medicare Advantage had higher levels of performance than traditional Medicare on clinical quality measures of diabetes care, including diabetic eye exam screening, diabetic cholesterol screening, and nephropathy care.175

The fourth study looked at measures of diabetes management by race and ethnicity, finding that while White beneficiaries had higher rates of foot examinations, flu shots, and cholesterol checks than Hispanic beneficiaries in both Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare, the disparity between White and Hispanic beneficiaries was narrower in Medicare Advantage than in traditional Medicare.176

Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in one Medicare Advantage Special Needs Plan (SNP) had lower mortality and lower utilization than traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Prior to 2021, beneficiaries with ESRD were not able to enroll in most Medicare Advantage plans, with the exception of some SNPs. Therefore, we were only able to identify one study that compared the quality of care received by beneficiaries with ESRD in traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage SNPs.177 The study found that enrollees with ESRD in a SNP had lower all-cause mortality and lower utilization across the care continuum compared to beneficiaries with ESRD in traditional Medicare. Because the analysis was limited to beneficiaries in a single health plan, CareMore Health, in three counties in California, findings may not be generalizable to other ESRD SNPs or Medicare Advantage plans more broadly.