The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Long-Term Prescription Painkiller Users and Their Household Members

Bianca DiJulio, Bryan Wu, and Mollyann Brodie

Published:

Overview

This partnership poll from The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation examines the long-term use of prescription painkillers by exploring the views and experiences of adults 18 and over who they themselves have taken strong prescription painkillers for a period of two months or more at some time in the past two years, other than to treat pain from cancer or terminal illness. The survey, conducted at a time when the nation is struggling to address the ongoing prescription painkiller and heroin epidemic, takes a closer look at long-term users of prescription painkillers to better understand how they started taking these drugs, their interactions with medical providers, their concerns and experiences with addiction, and their views of efforts to stem the abuse of painkillers. In addition, the survey also included household members of long-term users in order to capture their unique insight into how the drug use has impacted the individual.

This survey is the 30th in a series of surveys dating back to 1995 that have been conducted as part of The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation Survey Project.

Read The Washington Post’s Coverage

One-third of long-term users say they’re hooked on prescription opioids

Opioid drugs make pain tolerable, most long-term users say

An opioid epidemic is what happens when pain is treated only with pills

Editorial: The great opioid epidemic

The doctor you see in the ER may put you on a path toward long-term opioid use

Executive Summary

As the nation struggles to address the ongoing prescription painkiller and heroin abuse and overdose epidemic, The Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation Survey of Long-Term Prescription Painkiller Users and Their Household Members takes a closer look at those who are long-term users of prescription painkillers to better understand from their perspective what some of the drawbacks and benefits of the drugs are, as well as how they have impacted their lives. The survey explores how these long-term users started taking the drugs, their interactions with medical providers, their concerns and experiences with addiction, and their views of efforts to stem the abuse of painkillers. The survey was conducted among adults 18 and over who they themselves have taken strong prescription painkillers for a period of two months or more1 at some time in the past two years, other than to treat pain from cancer or terminal illness. In addition, the survey also included household members of long-term users in order to capture their unique insight into how the drug use has impacted the individual. Some of the key findings from this survey are noted below.

Long-Term Users Say They Started for Medical Reasons and Discussed Risks with Providers

- Nearly all long-term users of prescription painkillers say they started the painkillers with a prescription from a doctor and that they started taking them for chronic pain (44 percent), for pain after a surgery (25 percent) or for pain after an accident or injury (25 percent).

- Majorities say their doctor talked to them about the possibility of addiction or dependence, avoiding alcohol or other medications, and other ways to manage pain, but 61 percent say there was no discussion about a plan for getting off the painkillers. Still, a large majority (75 percent) say they think their doctor provided enough information on the risk of addiction and other side effects associated with prescription painkillers.

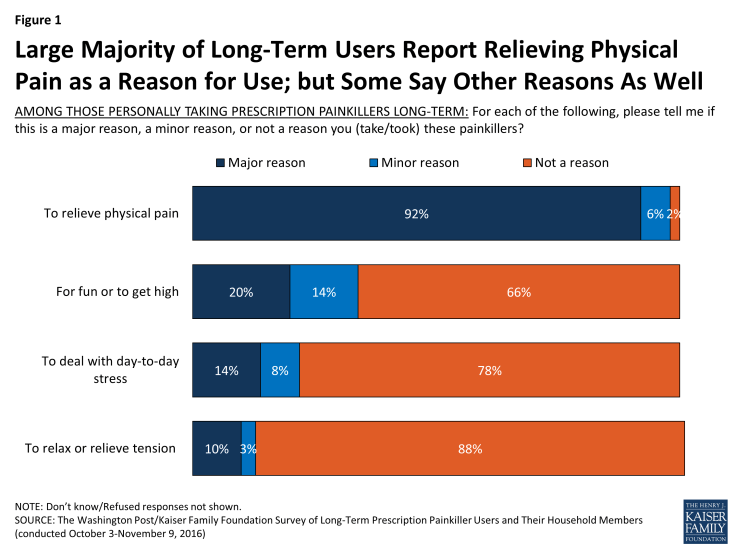

Disability and Poor Health Are Common Among Long-Term Users, Most Say Drugs Have Improved Life and Are Concerned About Crackdown

- They are a group that reports significant health issues such as a debilitating disability or chronic disease (70 percent), only fair or poor physical health (42 percent), or taking four or more prescription drugs (57 percent).

- A majority of long-term prescription painkiller users (57 percent) say it has made their quality of life better, but one in six (16 percent) say it has made it worse.

- With the recent attention prescription painkillers have received in light of the epidemic of abuse and overdose, two-thirds (67 percent) of long-term users say they are concerned that efforts to decrease the number of people abusing prescription painkillers will make it more difficult for them to access them.

Some Report Non-Medical Use, Addiction or Dependence, or Other Misuse

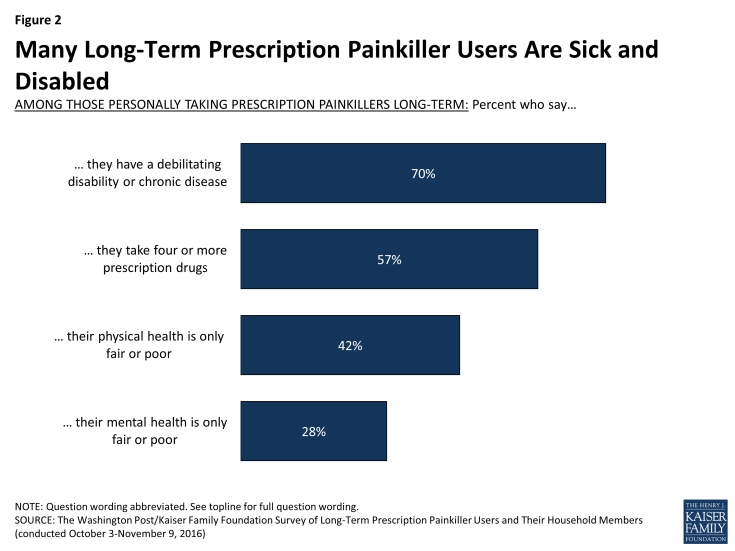

- While nearly all long-term users say they use the drugs to relieve pain, some also report that a major reason they take them is “for fun or to get high” (20 percent), “to deal with day-to-day stress” (14 percent), or “to relax or relieve tension” (10 percent). Only three percent of long-term users say that when they started, it was for recreational reasons.

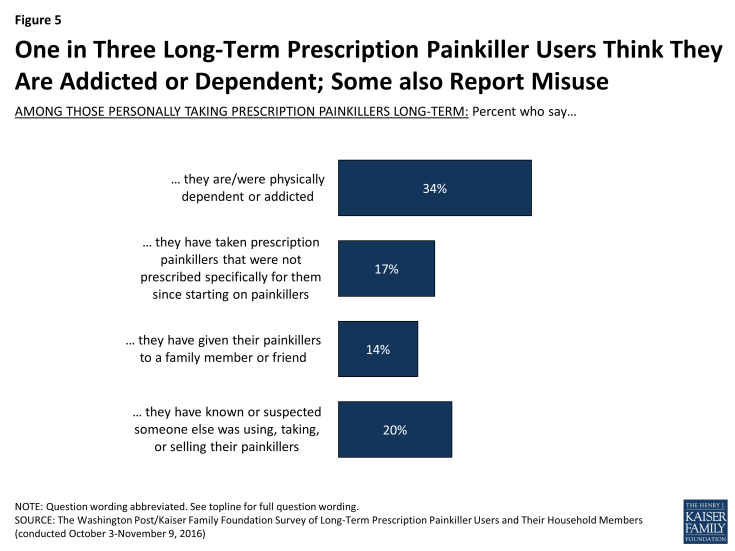

- Sizeable shares also report:

- being physically dependent or addicted to the painkillers (34 percent) (a group explored in detail in Section 2),

- they have taken prescription painkillers that were not prescribed specifically for them since starting on painkillers (17 percent),

- they have given their painkillers to a family member or friend (14 percent), and

- they have known or suspected someone was using, taking, or selling their painkillers (20 percent).

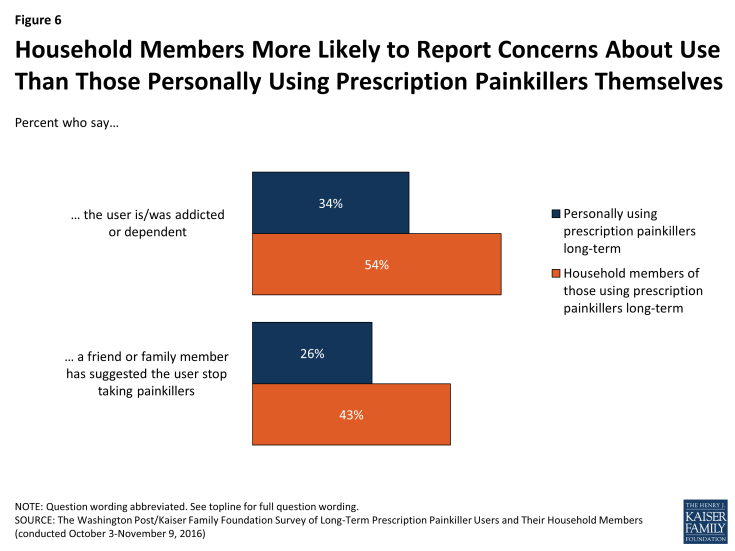

Household Members Generally Report More Negative Impacts

- Interviews with people living in the same household as a long-term prescription painkiller user provide another angle of insight into these individuals, be it their spouse, parent, or another household member.

- Household members are more likely to report they think the user is or was addicted or dependent and that their use has had a negative impact on their finances, personal relationships, and their health.

Views of the Painkiller Epidemic

- Majorities of people personally using prescription painkillers as well as people in their household say that people who use painkillers and doctors who prescribe painkillers deserve at least some of the blame for the painkiller addiction epidemic.

- When asked about a number of efforts what would be effective in reducing the abuse of prescription painkillers, long-term users point to efforts such as increasing pain management training for medical students and doctors (82 percent), increasing access to addiction treatment programs (80 percent), and increasing research about pain and pain management (81 percent).

Report

Introduction

Currently, the nation is struggling with an ongoing epidemic of prescription painkiller and heroin abuse and overdose, driven at least in part by a recent increase in the number of prescriptions written.1 Recognizing the role physicians play in prescribing strong painkillers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released guidelines for prescribing these medications and note the limited evidence of the efficacy of long-term use of prescription painkillers and concerns that the risks of addiction and adverse effects may outweigh their benefits.2 However, many people rely on prescription painkillers to provide relief from acute or chronic pain. As policymakers, medical professionals, and families weigh how to handle the ongoing epidemic and in order to better understand how long-term users came to use these drugs and their experiences while taking them, The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation conducted a survey of adults who they themselves, or a household member, have taken strong prescription painkillers for a period of two months or more at some time in the past two years, other than to treat pain from cancer or terminal illness. A time period of two months or more was selected to focus on those whose use may be at odds with current government guidelines around prescription painkiller use. We estimate that about 7 percent of adults in the U.S. fall into this category (5 percent), or have a household member who does (2 percent). What follows is a close look at their views and experiences with these painkillers, and how they view ongoing efforts to quell the epidemic.

Section 1: Views and Experiences of Long-Term Users of Prescription Painkillers

Why Did They Start Taking Strong Prescription Painkillers?

The vast majority of those taking strong prescription painkillers for two months or more report starting them with a prescription from a doctor (97 percent). More than four in ten of long-term users say they started taking them for chronic pain (44 percent), while 25 percent say they started due to pain after a surgery and another 25 percent say they started for pain after an accident or injury. Very few say they initially got the painkillers some way other than a doctor (3 percent) or that they started for recreational use (3 percent).

Many have been taking the painkillers for quite some time. Half (52 percent) of those personally using prescription painkillers say they have taken them for two years or more, but there are big differences depending on if they are still taking them or not. Most of those who say they no longer take them say they took them for 6 months or less (48 percent) and that they started them for pain after surgery (34 percent) or an accident or injury (27 percent). Seven in ten of those currently taking them have been on them for two years or more, and most started taking them for chronic pain (55 percent).

| Table 1: Length of Use and Reason for Starting Varies by Current Usage | ||||

| AMONG THOSE PERSONALLY USING PRESCRIPTION PAINKILLLERS LONG-TERM: | Total | Currently taking prescription painkillers (55%) | No longer taking prescription painkillers (45%) | |

| How long (have you been taking/did you take) these painkillers? | ||||

| 6 months or less | 28% | 12% | 48% | |

| More than 6 months but less than 1 year | 7 | 4 | 10 | |

| At least 1 year but less than 2 years | 13 | 14 | 12 | |

| 2 years or more | 52 | 70 | 30 | |

| Which of the following comes closest to the reason you began taking painkillers? | ||||

| Pain after surgery | 25% | 18% | 34% | |

| Pain after an accident or injury | 25 | 23 | 27 | |

| Chronic pain | 44 | 55 | 32 | |

| Recreational use | 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| NOTE: Started for some other reason (vol.) and Don’t know/Refused responses not shown. | ||||

Those no longer personally taking them point to a number of different reasons why they stopped, including that they no longer needed them for pain (60 percent of those not currently taking them), they were worried about becoming addicted (50 percent), they didn’t like the side effects (45 percent), and their prescription ended (34 percent).

Reasons for Taking Prescription Painkillers

While about nine in ten long-term prescription painkiller users report that relieving physical pain is a ‘major reason’ why they take the painkillers, some report taking the painkillers for other reasons as well. One in five say a major reason they take them is “for fun or to get high,” followed by 14 percent who say “to deal with day-to-day stress” and 10 percent who say “to relax or relieve tension.”

Figure 1: Large Majority of Long-Term Users Report Relieving Physical Pain as a Reason for Use; but Some Say Other Reasons As Well

Many Users Report a Disability and Multiple Prescriptions

Many personally taking prescription painkillers report being sick and disabled, such as saying they have a debilitating disability or chronic disease (70 percent) or that their physical health is only fair or poor (42 percent). More than half (57 percent) also say they take four or more prescription drugs, including 32 percent who report taking seven or more. These shares are significantly larger than for the general public. For example, 19 percent of the public reports having a chronic disease or disability1 and 18 percent say they are in fair or poor health.2

Compared to the general public, long-term users skew middle aged (59 percent between 40-64 versus 43 percent). Relatively few long-term users report working full-time (23 percent) or part time (8 percent) with more long-term users saying they are on disability (33 percent) or retired (20 percent). In comparison, six in ten of the general public report being employed, 18 percent say they’re retired, and 7 percent say they are on disability and can’t work.3

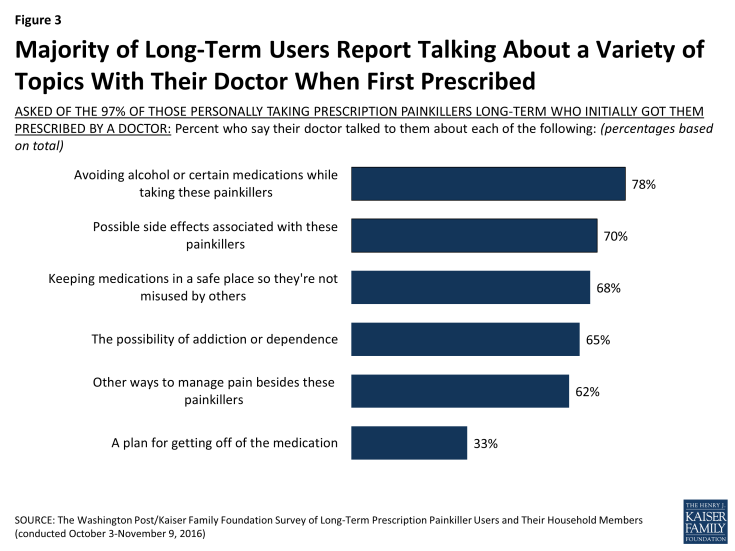

Interactions with Doctors

Most personally taking prescription painkillers long-term report that when their doctor first prescribed these medications, their doctor talked to them about:

- avoiding alcohol or certain medications while taking painkillers (78 percent);

- possible side effects associated with these painkillers (70 percent);

- keeping the medications in a safe place so they’re not misused by others (68 percent);

- the possibility of addiction or dependence (65 percent); and

- other ways to manage pain besides these painkillers (62 percent).

On the other hand, 61 percent say there was no discussion about a plan for getting off the painkillers when the doctor first prescribed them, while a third (33 percent) say there was.

Figure 3: Majority of Long-Term Users Report Talking About a Variety of Topics With Their Doctor When First Prescribed

In addition, 75 percent of long-term prescription painkiller users say they think their doctor provided enough information on the risk of addiction and other side effects associated with prescription painkillers. Still, one in five (19 percent) say their doctor did not provide enough information. For the most part, long-term users say that their doctor has not changed their dose (56 percent) or how often they take them (71 percent) since they started taking them. However, about two in ten (21 percent) say a doctor has increased their dose, and one in ten (10 percent) say their doctor has told them to take them more frequently.

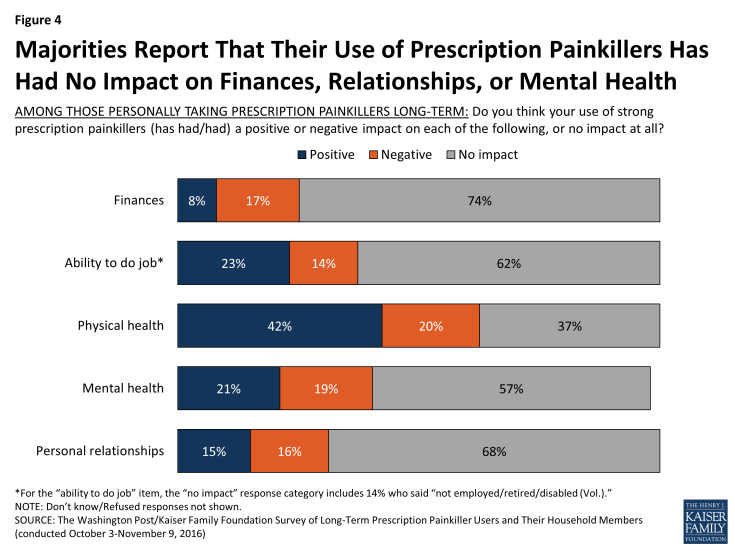

Impact on Life

Overall, long-term users report mostly positive effects of using painkillers. Virtually all long-term users (92 percent) say the painkillers have reduced their pain at least somewhat well. And, a majority of long-term prescription painkiller users (57 percent) say their use of the medications has made their quality of life better, particularly those who say they started the painkillers for chronic pain (69 percent), but one in six (16 percent) say it has made it worse.

In terms of the impact their use of the painkillers has had on certain aspects of their lives, most long-term users report that their use of the drugs has had no impact on their finances (74 percent) however more say the impact has been negative than say positive (17 percent versus 8 percent). But when it comes to their impact on their physical health or their ability to do their job, more say the impact has been positive than say negative (42 percent vs. 20 percent and 23 percent vs. 14 percent, respectively). Most say there has been no impact on their mental health or personal relationships, but for those that do, similar shares say the impact has been positive as say negative.

Figure 4: Majorities Report That Their Use of Prescription Painkillers Has Had No Impact on Finances, Relationships, or Mental Health

Reports of Addiction, Dependence and Misuse

In addition to some reporting negative impacts on their lives, 34 percent report that they think they are or were physically dependent or addicted to the painkillers (this group is profiled in Section 2). Few (9 percent) say they have sought treatment for addiction and 2 percent say they have considered seeking addiction treatment. Additionally, a quarter (26 percent) say that a friend or family member has suggested they stop taking them.

There are also a number of indications of misuse among long-term users, including 17 percent who say they have taken prescription painkillers that were not prescribed specifically for them since starting on painkillers and 14 percent who say they have given their painkillers to a family member or friend. In addition, 20 percent say they have known or suspected someone was using, taking, or selling their painkillers, rising to nearly three in ten (28 percent) of long-term users in rural areas, compared to 10 percent of those in urban areas.

Figure 5: One in Three Long-Term Prescription Painkiller Users Think They Are Addicted or Dependent; Some also Report Misuse

Risky Use

Many are taking other drugs that could put them more at risk for an overdose or other complications. About half (52 percent) of long-term users say that while taking their prescription painkillers they were taking other prescription medications for anxiety, depression, or sleep problems. And, 18 percent say that while taking their prescription painkillers they have consumed alcohol.

Perceptions of Risk

Two-thirds (68 percent) of those personally using prescription painkillers long-term say that the benefits of pain relief outweigh the risk of addiction. However, nearly half (46 percent) acknowledge that using them makes a person more likely to use heroin or other illegal drugs and 40 percent say prescription painkillers are as addictive as heroin.

Compared to those personally using strong painkillers, the general public is more split on the risks and benefits of using prescription painkillers for more than a week, and are more likely than those personally using to say prescription painkiller use makes a person more likely to use heroin or other illegal drugs or that prescription painkillers and heroin are equally addictive.

| Table 2: Long-Term Users’ and General Public’s Perceptions of Prescription Painkiller Risk | ||

| Personally taking prescription painkillers long-term | U.S. Adults | |

| Which comes closer to your view on using prescription painkillers for more than a week to treat pain? | ||

| The risk of addiction outweighs the benefits of pain relief | 25% | 47% |

| The benefits of pain relief outweigh the risk of addiction | 68 | 44 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 6 | 9 |

| Do you think prescription painkiller abuse makes a person more likely or less likely to use heroin or other illegal drugs, or do you think it doesn’t make much of a difference? | ||

| More likely | 46% | 58% |

| Less likely | 4 | 2 |

| Doesn’t make much of a difference | 43 | 36 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 7 | 4 |

| Which do you think is more addictive, prescription painkillers or heroin, or do you think they are about equally addictive? | ||

| Prescription painkillers | 3% | 6% |

| Heroin | 45 | 29 |

| Equally addictive | 40 | 60 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 12 | 6 |

| SOURCE: National comparison of U.S. adults from Kaiser Health Tracking Poll (conducted November 15-21, 2016) | ||

Access to Prescription Painkillers: Users’ Troubles and Concerns

Reports of Problems Accessing Painkillers

Some of those personally using prescription painkillers long-term report trouble accessing them, including trouble affording them (18 percent), getting a pharmacy to fill a prescription (16 percent), getting refill from doctors (16 percent), and getting insurance to cover it (12 percent). Overall, 41 percent of long-term users report at least one of these issues. With the recent attention prescription painkillers have received in light of the epidemic of abuse and overdose, two-thirds (67 percent) of long-term users say they are concerned that efforts to decrease the number of people abusing prescription painkillers will make it more difficult for them to access them; a share that increases to nearly eight in ten (78 percent) of those who started to treat chronic pain, including 56 percent who say they are very concerned.

Six in ten (60 percent) long-term users say it is easy for people to get painkillers that were not prescribed to them, while a similar share (59 percent) say it is difficult for people who need the drugs for medical purposes to get them. Majorities of the general public say it is easy to get drugs in both scenarios, although a larger share say it’s easy for people to get drugs not prescribed to them than say the same about those who need them for medical purposes.

| Table 3: Perceptions of Prescription Painkiller Accessibility Among Long-Term Users and the General Public | ||

| How easy or difficult do you think it is for people… | Personally taking prescription painkillers long-term | U.S. Adults |

| … to get access to prescription painkillers that were NOT prescribed to them? | ||

| Easy (NET) | 60% | 71% |

| Very easy | 36 | 37 |

| Somewhat easy | 24 | 33 |

| Difficult (NET) | 27 | 27 |

| Somewhat difficult | 14 | 17 |

| Very difficult | 14 | 10 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 13 | 3 |

| … who need prescription painkillers for medical purposes to get access to them? | ||

| Easy (NET) | 36% | 62% |

| Very easy | 16 | 28 |

| Somewhat easy | 20 | 34 |

| Difficult (NET) | 59 | 35 |

| Somewhat difficult | 30 | 24 |

| Very difficult | 29 | 12 |

| Don’t know/Refused | 5 | 3 |

| SOURCE: National comparison of U.S. adults from Kaiser Health Tracking Poll (conducted November 15-21, 2016) | ||

Side Effects

Prescription painkillers are known for causing certain side effects, and among long-term users, reports of side effects are quite common. Seven in ten (72 percent) of those personally using prescription painkillers report experiencing at least one of the following side effects: constipation (55 percent), indigestion, dry mouth, or nausea (50 percent) or breathing problems (15 percent). While many have experienced side effects, half (50 percent) say they have not taken medications specifically to treat side effects. However, one in five (21 percent) say they have.

Half (49 percent) of those personally using painkillers say they are at least somewhat concerned about side effects, including one in four (27 percent) who say they are very concerned, and nearly half of those who no longer take the painkillers say that the side effects are at least a minor reason they stopped (45 percent, or 20 percent of long-term users overall). Still, large majorities say their doctor discussed possible side effects when they initially prescribed the painkillers (70 percent) and feel their doctor provided enough information about the risk of addiction and other side effects (75 percent).

Views and Experiences from Household Members of Prescription Painkiller Users

Interviews with people living in the same household as a long-term prescription painkiller user provide another angle of insight into this group. For most, the user is a spouse (43 percent), followed by a parent (25 percent), a child (9 percent), or some other person in their household (21 percent).

Household Members Report Negative Impacts, Concerned About Addiction

In general, household members are more likely to report issues with addiction or dependence and negative experiences than those who are personally taking the painkillers. For example, 54 percent of household members say they think the person is or was addicted or dependent and 43 percent report that a friend or family member has suggested the user stop.

Figure 6: Household Members More Likely to Report Concerns About Use Than Those Personally Using Prescription Painkillers Themselves

In addition, household members are roughly twice as likely as those personally using prescription painkillers to say the drugs have had a negative impact on the user’s finances (37 percent versus 17 percent), the user’s personal relationships (34 percent versus 16 percent), the user’s physical health (39 percent versus 20 percent), the user’s mental health (39 percent versus 19 percent), and the user’s ability to do their job (27 percent versus 14 percent).

Section 2: A Focus on Those Reporting They Are Physically Dependent or Addicted

Of those personally using prescription painkillers, about a third (34 percent) say they think they are or were addicted or physically dependent on them,1 which accounts for about 2 percent of adults in the U.S. This section examines their views and experiences more closely. Like long-term prescription painkiller users generally, many who say they are or were addicted or dependent say they started for chronic pain (47 percent), a quarter (25 percent) say they started for pain after a surgery, and 19 percent say they started after an injury or accident. Six percent say they started using recreationally.

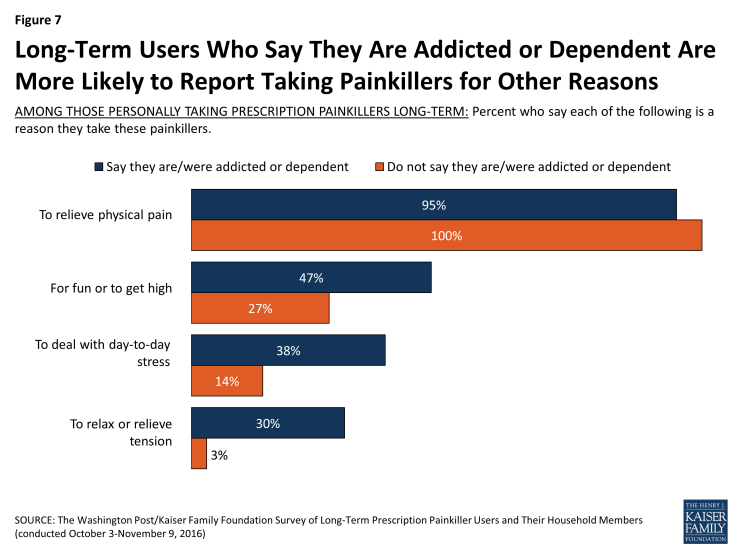

Nearly all (95 percent) of those saying they’re addicted or dependent say that relieving physical pain is a reason they’re taking the drugs. However, they are much more likely than others to say they’re taking them for other reasons as well, such as for fun or to get high (47 percent versus 27 percent), to deal with day-to-day stress (38 percent versus 14 percent), or to relax or relieve tension (30 percent versus 3 percent).

Figure 7: Long-Term Users Who Say They Are Addicted or Dependent Are More Likely to Report Taking Painkillers for Other Reasons

Not surprisingly, those who say they are or were dependent or addicted also are more likely than others to report being concerned about addiction (49 percent versus 25 percent) and to report misuse, such as taking painkillers not prescribed to them (30 percent versus 10 percent) or giving them to a family member or friend (21 percent versus 11 percent). They are also more likely than others to say they know or suspect someone has taken their pills (28 percent versus 15 percent) and to report that a family or friend has suggested they stop taking the medication (40 percent versus 18 percent).

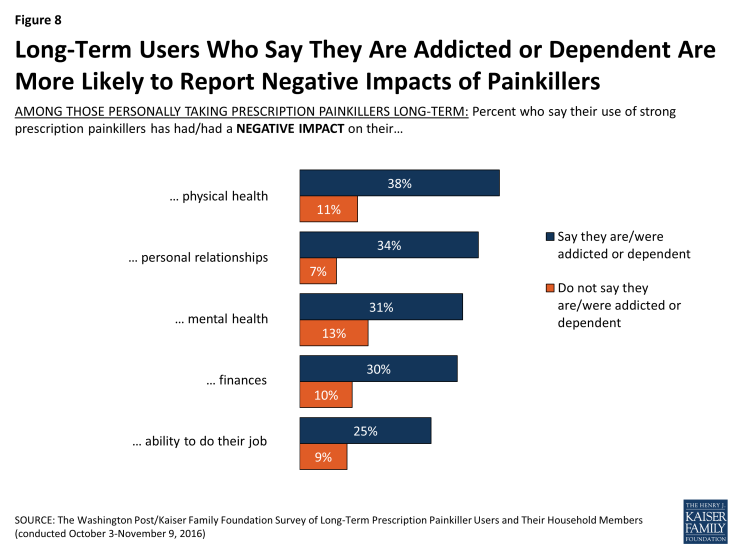

About a quarter (24 percent) of those who report being addicted or dependent say they think their quality of life is worse after taking these medications, compared to 12 percent of those who do not say they are addicted or dependent. They’re also more likely than those not reporting addiction or dependence to say it’s had a negative impact on their finances, their personal relationships, their employment, their physical health, and their mental health.

Figure 8: Long-Term Users Who Say They Are Addicted or Dependent Are More Likely to Report Negative Impacts of Painkillers

Among those who say they are or were addicted or dependent, three in ten (31 percent) feel their doctor did not provide enough information about the risk of addiction and other side effects, but they are similar to others in terms of reporting that their doctor talked to them about the possibility of addiction or dependence or a plan to get off medications. They’re more likely than others to say they have had trouble with at least one of the following: getting a prescription written or filled, affording the drugs, or getting insurance to pay for them (58 percent versus 33 percent). Eight percent say they have a prescription for Narcan or Naloxone at home, a drug that can reverse the effects of prescription painkillers and prevent overdose.

Controlling for factors such as income and region, younger adults (18-39), Hispanics, and those who report taking the painkillers for two or more years are more likely than their counterparts to report being addicted or dependent on the drugs.

Section 3: Views of Prescription Painkiller Epidemic

Prescription Painkiller Abuse Is One of Many Serious Health Issues

For those personally using prescription painkillers long-term, the abuse of painkillers ranks last on a list of health issues facing the country today. Those personally using in the South (73 percent) are more likely to say opioid abuse is a very serious problem than those in the Midwest (60 percent) or West (41 percent).

| Table 4: Abuse of Prescription Painkillers Ranks Low Among Several Health Issues, But Majorities Say Abuse Is a Very Serious Problem | ||

|

Percent who say each health issue is a VERY SERIOUS problem in this country:

|

Personally taking prescription

painkillers long-term

|

U.S. Adults |

| Cancer | 87% | 82% |

| Heart Disease | 75 | 70 |

| Heroin Abuse | 74 | 72 |

| Diabetes | 74 | 68 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 67 | 52 |

| Obesity | 64 | 63 |

| Abuse of Strong Prescription Painkillers | 62 | 66 |

| NOTE: Some items asked of half samples. Question wording abbreviated. See topline for full question wording. SOURCE: National comparison of U.S. adults from Kaiser Health Tracking Poll (conducted November 15-21, 2016) |

||

Who’s To Blame For Epidemic?

Majorities of people personally using prescription painkillers as well as people in their household say that people who use painkillers and doctors who prescribe them deserve at least some of the blame for the ongoing epidemic. In addition, two-thirds (65 percent) of opioid users’ household members say they blame drug companies and half (49 percent) say they blame the government. Ranking lower on the list for both groups are law enforcement and pharmacies and pharmacists.

|

Table 5: Views of Long-Term Users, Their Household Members, and the General Public on

Who Is to Blame for the Prescription Painkiller Addiction Epidemic

|

|||

| Percent who say each of the following deserve A LOT or SOME blame for the prescription painkiller addiction epidemic: | Personally taking prescription painkillers long-term | Household members of those using prescription painkillers long-term | U.S. Adults |

| People who use painkillers | 61% | 65% | 68% |

| Doctors who prescribe painkillers | 54 | 66 | 69 |

| Drug companies | 47 | 65 | 60 |

| The government | 40 | 49 | 44 |

| Hospitals | 27 | 44 | 43 |

| Law enforcement | 17 | 14 | 28 |

| Pharmacies and pharmacists | 15 | 19 | 28 |

| NOTE: Some items asked of half samples of the general public. SOURCE: National comparison of U.S. adults from Kaiser Health Tracking Poll (conducted November 15-21, 2016) |

|||

Effective Strategies for Combatting the Epidemic

When asked what would be effective in reducing the abuse of prescription painkillers, eight in ten of those personally taking opioids say increasing pain management training for medical students and doctors (82 percent), increasing research about pain and pain management (81 percent), and increasing access to addiction treatment programs (80 percent). Large majorities also say encouraging people who were prescribed painkillers to dispose of any extras once they no longer medically needed them (73 percent), public education and awareness programs (72 percent), and monitoring doctors’ prescribing habits (69 percent) would be effective. Roughly half say reducing the social stigma around addiction (54 percent), putting warning labels about addiction on drug bottles (50 percent), and government limits on the amount of drugs that can be produced (47 percent). These responses are generally similar to what the public feels would be effective. The general public is somewhat more likely than those personally using to say the following would be effective: public education and awareness programs (86 percent vs. 72 percent), monitoring doctors’ prescription painkiller prescribing habits (83 percent vs. 69 percent), and increasing pain management training for medical students and doctors (89 percent vs. 82 percent).

Methodology

The Washington Post/Kaiser Family Foundation Survey Project is a partnership combining survey research and reporting to better inform the public. The Post-Kaiser Survey of Long-Term Prescription Painkiller Users and Their Household Members, the 30th in this series was conducted by telephone October 3 – November 9, 2016, among a representative random national sample of 809 adults age 18 and over who they themselves, or a household member, have taken strong prescription painkillers for a period of two months or more1 at some time in the past two years, other than to treat pain from cancer or terminal illness. Interviews were administered in English and Spanish, combining random samples of both landline (n=266) and cellular telephones (n=543).

Sampling, data collection, weighting and tabulation were managed by SSRS in close collaboration with The Washington Post and Kaiser Family Foundation researchers.

The SSRS Omnibus survey (detailed below) estimates that about seven percent of adults in the U.S. have either themselves used strong prescription painkillers in the past two years for two months or more, other than to treat pain from cancer or terminal illness (five percent), or have a household member that has (two percent). Due to the low-incidence of this study population, the sampling was designed to increase efficiency in reaching this group by using the following sample sources:

- Cell and Landline Phone Random Digit Dialing (RDD) (n=354): The dual frame landline and cellular phone sample was generated by Marketing Systems Group (MSG) using RDD procedures. Interviewers calling landline phone numbers asked to speak with an adult currently at home on a random rotation. Interviews calling cellular phones interviewed the person answering the phone after verifying eligibility.

- Respondents Previously Completing Interviews on the SSRS Omnibus Survey (n=455). Weekly, RDD landline and cellular phone surveys of the general public were used to identify eligible respondents. Individuals who had previously indicated on the SSRS omnibus survey that they fit the eligibility criteria for this study were re-contacted.

Regardless of the sample source, all respondents were screened to verify that they have taken a strong prescription painkiller for a period of two months or more in the past two years or have a household member who has, other than to treat pain from cancer or terminal illness. If a respondent indicated that both themselves and a household member qualified, they completed the questionnaire about their own personal use. The screening questions are identified at the beginning of this document as S3 through S5.

A multi-stage weighting design was applied to ensure an accurate representation of the population of long-term strong prescription drug users and their household members. The first stage of weighting involved corrections for sample design, including accounting for non-response for the re-contact sample. In the second weighting stage, demographic adjustments were applied to account for systematic non-response along known population parameters. No reliable administrative data were available for creating demographic weighting parameters for this group. Therefore, demographic benchmarks were derived by compiling a sample of all respondents interviewed on the SSRS Omnibus survey between August 18, 2016 and November 9, 2016 (N=15,944) and weighting this sample to match the national adult population based on the 2016 U.S. Census Current Population Survey March Supplement parameters for age, gender, education, race/ethnicity, region, phone status, and population density. This sample was then filtered to include respondents qualifying for the current survey (N=1,122), and the weighted demographics of this group were used as post-stratification weighting parameters for the total sample (including age by gender, education, race/ethnicity, region, population density, self or household member prescription painkiller user, and phone status).

All sampling error margins and tests of statistical significance have been adjusted to account for the survey’s design effect, which is 1.6 for this survey. The design effect is a factor representing the survey’s deviation from a simple random sample, and takes into account decreases in precision due to sample design and weighting procedures. Sample sizes and margin of sampling errors for key groups are shown below; other subgroups are available by request. Note that sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error in this or any other public opinion poll.

| Table 6: Sample Size and Margin of Sampling Error | ||

| Group | N (unweighted) | Margin of sampling error (percentage points) |

| Total | 809 | ±4 |

| Interview type | ||

| Personal user | 622 | ±5 |

| Household interview | 187 | ±9 |

| Among personal users | ||

| Report being addicted or dependent | 200 | ±9 |

| Do not report being addicted or dependent | 422 | ±6 |

This questionnaire was administered with the exact questions in the exact order as appears in this document. If a question was asked of a reduced base of the sample, a parenthetical preceding the question identifies the group asked. Current users were asked the questions in the present tense, indicated where applicable in the first part of the parenthetical text within the question. Past users were asked the questions in the past tense and read the language in the second half of the parentheses. In addition, those personally using were asked the questions directly about their use, whereas household members were asked about the user in most cases, as indicated in the questions.

Since some of the questions could be sensitive and due to the nature of the survey content, interviewers were given specific instructions on how to cope with respondents who seemed agitated or distressed by the questions, including offering resources to which respondents could turn for support.

The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation each contributed financing for the survey, and representatives of each organization worked together to develop the survey questionnaire and analyze the results. Each organization bears the sole responsibility for the work that appears under its name. The project team from the Kaiser Family Foundation included: Mollyann Brodie, Ph.D., Bianca DiJulio, and Bryan Wu. The project team from The Washington Post included: Scott Clement and Emily Guskin. Both The Washington Post and the Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research are charter members of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

Endnotes

Executive Summary

A time period of two months or more was selected to focus on those whose use may be at odds with current government guidelines around prescription painkiller use.

Report

Introduction

Frieden, T. and Houry, D. “Reducing the Risks of Relief – The CDC Opioid-Prescribing Guideline,” The New England Journal of Medicine, April, 2016, http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1515917.

Dowell, D., Haegerich, T., and Chou, R. “CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain- United States, 2016,” JAMA, April, 2016, available at http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2503508.

Section 1: Views and Experiences of Long-Term Users of Prescription Painkillers

Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Health Tracking Poll, August 2016, https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-august-2016/

Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Health Tracking Poll, November 2016, https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-november-2016/

Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser Health Tracking Poll, November 2016, https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/poll-finding/kaiser-health-tracking-poll-november-2016/

Section 2: A Focus on Those Reporting They Are Physically Dependent or Addicted

We use a combined measure of those who say they are or were addicted OR physically dependent on prescription painkillers. We chose to use this combined measure given people’s potential for misunderstanding ‘dependence’ or their potential unwillingness to say they’re addicted due to social desirability reasons. The 34 percent who say they are addicted or dependent is comprised of 21 percent who say they are both addicted and dependent, 11 percent who say they’re only dependent, and 2 percent who say they’re only addicted. Overall, responses are similar for those saying they’re addicted and those saying they’re dependent.

Methodology

A time period of two months or more was selected to focus on those whose use may be at odds with current government guidelines around prescription painkiller use.