What We Know About Provider Consolidation

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to dramatic decreases in health care spending, as patients and providers have delayed a wide range of health care services. The decrease in service use and spending resulted in a decline in revenue for many providers at the same time that some are facing increased costs due to the pandemic. Given the uncertain timing of a “return to normal” and potentially lingering effects of the current economic crisis, some providers may continue to experience sustained declines in revenue even with the federal assistance that has been made available.1

Depending on the severity and duration of revenue loss, some hospitals and physician practices may find it difficult to operate independently, which could increase the rate of consolidation among health care providers. Lower margins among some providers may create new opportunities for large chains to acquire smaller providers. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act allocated $175 billion for grants to providers that were partly intended to help make up for revenue lost due to coronavirus, but analysis shows that the first $50 billion in grants were not targeted to providers most vulnerable to revenue losses.2 Another $13 billion was subsequently targeted to safety net hospitals and $11 billion has been targeted to rural providers.3 However, it is not clear whether this infusion of funds plus other government loans—including those from the Paycheck Protection Program—will be sufficient to stabilize providers who are least equipped to weather this revenue decline. Even if sufficient government assistance is provided, the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic may make operating independently seem less attractive and riskier to some smaller providers. Therefore, financial assistance to providers may not be sufficient to prevent an increase in the pace of consolidation.

This brief provides an overview of existing research that examines the impact of provider consolidation on health care costs and quality. There are two major types of consolidation among health care providers, both of which are discussed in this brief. The first is horizontal consolidation, which occurs when two providers performing similar functions join, such as when two hospitals merge or groups of physician practices merge to form larger group practices. The second type is vertical integration, which refers to one type of entity purchasing another in the supply chain such as hospitals acquiring physician practices.4

Provider consolidation leads to higher prices

A wide body of research has shown that provider consolidation leads to higher health care prices for private insurance; this is true for both horizontal and vertical consolidation. In Medicare, payment policies protect Medicare from increased prices due to horizontal consolidation but have led to higher Medicare costs in the case of vertical consolidation. However, recent administrative and legislative changes are bringing Medicare reimbursement at hospital outpatient departments in line with reimbursement at independent physicians’ offices.

Horizontal consolidation among hospitals

In 2020, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) reviewed the published research on hospital consolidation and concluded that the “preponderance of evidence suggests that hospital consolidation leads to higher prices.”5 For example, one analysis looking at 25 metropolitan areas with the highest rates of hospital consolidation from 2010 through 2013 found that the price private insurance paid for the average hospital stay increased in most areas between 11% and 54% in the subsequent years.6 A separate analysis of data from employer-sponsored coverage found that hospitals that do not have any competitors within a 15-mile radius have prices that are 12% higher than hospitals in markets with four or more competitors.7 Another analysis of all hospital mergers over a five year period found that mergers of two hospitals within five miles of one another resulted in an average price increase of 6.2% and that price increases continued in the two years after a merger.8 A similar study found that mergers of two hospitals in the same state led to price increases of 7% to 9% for the acquiring hospitals.9 Studies have found that these patterns hold even when looking specifically at non-profit hospitals.10 While health plans may try to keep hospital prices low, health plans’ ability to successfully hold down prices is limited in many parts of the country because they have less market power than hospitals.11

Even when a hospital merges with a hospital in a different geographic area, some studies suggest that the merger can impact competition and prices. One analysis found that prices at hospitals acquired by out‐of‐market hospital systems increase by about 17% more than unacquired, stand‐alone hospitals.12 This study also found that this type of merger has a spillover impact on market dynamics in the area where the acquired hospital is located— with prices of nearby competitors to acquired hospitals increasing by around 8%.13 One reason that prices rise when there are hospital mergers across markets is that they increase hospital bargaining positions with insurers, which seek to have strong provider networks across multiple areas in order to attract employers with employees in multiple locations.14 Additionally, large hospital systems can influence the dynamics of negotiations with insurers and shift volume to higher cost facilities. For example, hospital systems may require that insurers include all hospitals in their system in a provider network if the insurer wants any hospitals included. This can lead to higher cost hospitals being in a provider network even when there are lower cost hospitals nearby. In one recent anti-trust case, the Sutter Health system was accused of violating California’s antitrust laws by using its market power to illegally drive up prices.15 In a 2019 settlement, Sutter Health agreed to stop requiring that all of its hospitals be included in an insurer’s network and also agreed to pay damages and make other changes.16

Horizontal consolidation among physicians

Patterns of consolidation leading to higher prices also have been observed when physician practices merge. A national study found that physicians in the most concentrated markets charged fees that were 14% to 30% higher than the fees charged in the least concentrated markets.17 Another national study comparing physician prices in counties with highly concentrated physician markets to counties with the least concentrated physician markets found higher prices for physicians practicing in the most concentrated counties across specialty types.18 A study that examined the effects of a merger of six orthopedic groups in Pennsylvania found that the merger was associated with price increases ranging from 15% to 25% across payers.19

Vertical consolidation

Vertical consolidation also leads to higher prices, which can then lead to higher premiums. One study analyzing highly concentrated hospital markets in California found that an increase in the share of physicians in practices owned by a hospital was associated with a 12% increase in premiums for private plans sold in the state’s Marketplace.20 Another study that used private insurer data found that an increase in physician-hospital integration was associated with an average price increase of 14% for the same service.21 Those findings are consistent with another study that used private insurance data that found a large increase in physician-hospital vertical integration was associated with an increase in outpatient prices.22 A study looking at Medicare beneficiaries’ patterns of health care utilization found that “patients are more likely to choose a high-cost, low-quality hospital when their physician is owned by that hospital.”23

Insurance markets and consolidation

When insurance markets become more consolidated, there are two distinct impacts. As insurance companies consolidate and have more market power, evidence suggests that they are able to obtain lower prices from providers. For example, one study looking at the impact of health plan concentration on hospital prices found that hospital prices in the most concentrated health plan markets were approximately 12% lower than in more competitive health plan markets.24 Another study found a similar pattern for both hospitals and some types of specialists.25 However, these lower prices do not necessarily lead to lower premiums. A national study found that lower provider prices only translate into lower premiums if the insurance market is sufficiently competitive; where health insurance markets are more concentrated, premiums tend to be higher.26 The impact on premiums may be somewhat mitigated for fully insured plans by the minimum loss ratio requirement in the Affordable Care Act, which limits the amount of the premium that insurers can keep.

Consolidation and Medicare prices

Private insurance rates are the result of negotiations between providers and payers, which means providers with market power due to consolidation have greater leverage to raise prices in these negotiations. In contrast, Medicare prices are set by formulas and government policies. Horizontal consolidation does not impact Medicare prices for physicians or hospitals that are generally paid based on the prospective payment systems.27 However, once a physician’s office has been purchased by a hospital, that hospital had historically been able to obtain higher Medicare rates by billing as a hospital outpatient department for services at that physician’s location.

Both Congress and the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) have made policy changes over the past several years to lower costs for off-campus hospital outpatient clinics to bring them in line with physicians’ offices, despite industry opposition. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA) required that Medicare reimburse for services delivered at new, off-campus hospital outpatient departments using rates based on the physician fee schedule instead of the higher rates for outpatient hospital departments. However, this change grandfathers off-campus outpatient departments that billed for services, rendered services, or were being constructed before November 2, 2015. Beginning in 2019, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) lowered payment rates in grandfathered off-campus departments for a clinic visit—the single highest volume service provided by hospital outpatient departments—to 70% of the full hospital outpatient rate in 2019 and 40% of the full hospital outpatient rate in 2020. Several hospital associations challenged CMS’ authority for this policy. On September 17, 2019, the DC District Court vacated CMS’s regulation for being inconsistent with the statute. On July 17, 2020, the DC Circuit Court reversed the District Court’s decision, allowing the regulation to stay in place.

HHS’s regulatory change to lower payments at hospital outpatient departments is consistent with MedPAC’s recommendation to adjust Medicare payments so that those locations are reimbursed at the same rates as physician’s offices.28 While HHS’s change does not directly impact Medicare Advantage plans, there is some evidence that Medicare Advantage plans typically pay rates that are similar to payments under traditional Medicare.

Mergers have led to more consolidation, even before the financial pressures brought on by COVID-19

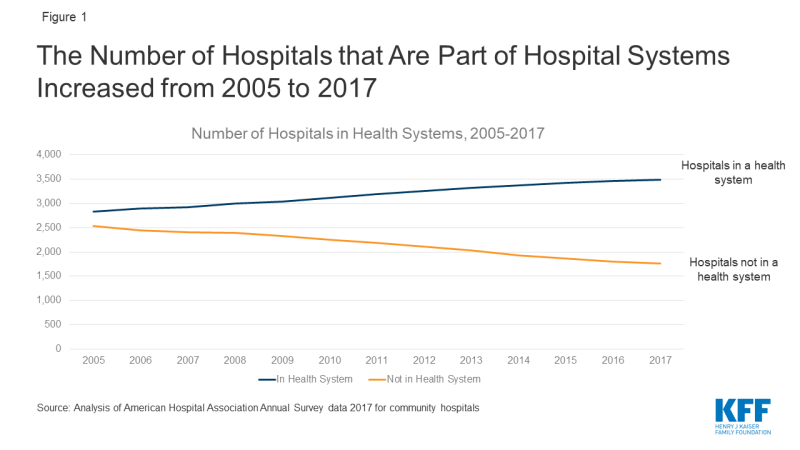

Between 2010 and 2017, there were 778 hospital mergers.29 Over time, the number of independent hospitals has declined as a result of these mergers, while the number of hospitals that are part of larger systems has risen (Figure 1). By 2017, two thirds (66%) of all hospitals were part of a larger system, as compared to 53% in 2005.30

In 2010, most hospital markets were already dominated by a limited number of health systems: on average, the three largest health systems in a given area accounted for more than three-quarters of admissions.31 In the subsequent years, health care markets have continued to become more consolidated, as measured using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index. This index is a commonly used measure of market concentration that is calculated for a given market based on the number of competing providers and each of these providers’ relative market share. From 2010 to 2016, the mean Herfindahl-Hirschman Index for metropolitan statistical areas in the United States for hospitals and specialist physician organizations each increased by about 5% on average.32 Over the same period, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index for primary care practices increased by 29% on average in metropolitan statistical areas nationwide.33 Using this index, 90% of metropolitan statistical areas were highly concentrated for hospitals, 65% were highly concentrated for specialists and 39% were highly concentrated for primary care physicians by 2016.34

Much of the increase in consolidation among physician practices is due to acquisition by hospitals. The proportion of primary care physicians practicing in organizations owned by a hospital or health system grew from 28% in 2010 to 44% in 2016.35 By 2018, data from the American Medical Association shows that 35% of all practicing physicians worked either directly for a hospital or in a practice at least partly owned by a hospital in 2018.36

Among health insurance markets, 57% of metropolitan statistical areas were highly concentrated in 2016 for private insurance, and the average Herfindahl-Hirschman Index for insurers was relatively steady between 2010 and 2016.37 Meanwhile, the market for the private Medicare Advantage plans available to Medicare beneficiaries has become increasingly concentrated. Medicare Advantage plans are mainly health maintenance organizations (HMOs) and preferred provider organizations (PPOs) and receive payments from Medicare to cover Medicare enrollees. The total market share of the top four Medicare Advantage insurers increased from 48% in 2011 to 61% in 2015.38 As of 2020, the top four Medicare Advantage insurers controlled 70% of the market.39

The role of private equity

Private equity has started to play a role in this consolidation in recent years. These firms typically invest in businesses by taking a majority stake with the goal of increasing the value of the business and potentially selling it at a profit. One study found that private equity firms acquired 355 physician practices (1,426 sites and 5,714 physicians) from 2013 to 2016.40 The pace of these acquisitions increased over the study period, with 59 practices acquired in 2013 and 136 practices acquired in 2016.41 While these acquisitions represent a small share of the 18,000 unique group medical practices in the United States, the trend is worth monitoring given the unique business model of these firms.42 Private equity firms often sell their investments within three to seven years, so they may have a short time horizon for evaluating investments in improving medical providers.43 Acquisition by a private equity firm can lead to more consolidation later, as these firms often then acquire additional nearby practices as part of their business model.44 A study on the impact of private equity acquisitions of hospitals found that hospitals acquired by private equity firms reported larger increases in annual net income and hospital charges than similarly situated hospitals not acquired by private equity firms.45

Anti-trust enforcement challenges and opportunities

In health care, along with other sectors of the economy, enforcement of federal and state anti-trust laws is supposed to ensure competitive markets that benefit consumers. At the federal level, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is charged with reviewing mergers. In the past, the FTC has blocked some hospital and physician mergers,46 but the overall health care market has continued to become increasingly consolidated. FTC officials have cited several constraints on their ability to enforce anti-trust laws in the health care sector that may be contributing to the increases in consolidation in recent years.47 Specifically, the FTC and Department of Justice’s anti-trust division have seen their budgets remain flat from 2010 to 2016, even as the pace of health care mergers has increased.48 Vertical integration is particularly challenging for the FTC to monitor because it is often the result of hospitals acquiring many smaller practices and each of those transactions may fall under the threshold of having to notify FTC.49, 50

Once a merger has taken place, states and the federal government can still enforce anti-trust laws. This can include pursing actions to stop anti-competitive practices such as a health care provider with significant market power preventing insurers from giving incentives to enrollees to go to less expensive providers.51 However, there is an important limitation on the FTC’s enforcement ability. The FTC Commissioner, Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, has raised concerns that the FTC is not able to enforce anti-trust rules on non-profit hospitals, although it can review mergers that involve a non-profit hospital.52 Nationally, 57% of all hospitals are non-profit.53 In 2019, 66% of the total hospital and health system mergers and acquisitions involved a non-profit entity purchasing another non-profit entity.54

States can serve as another potential check on anti-competitive mergers and can sue under federal anti-trust law and enforce their own laws. A recent review of state anti-trust enforcement in health care identified several practices that support robust enforcement.55 These include adequate notice requirements for potential mergers and waiting periods for state reviews; established criteria for merger review and the ability to conduct a full analysis of economic and health care implications; and the ability to implement post-merger monitoring.56

There is no clear evidence that consolidation improves quality of care

While provider consolidation holds the promise of greater efficiencies and better care coordination, evidence of the benefits of improved quality after a merger are mixed at best, and some studies suggest that market consolidation—particularly for horizontal consolidation—can actually lead to lower quality care. It is difficult and takes time and resources to achieve true integration of care among newly merged health systems, while price increases often occur immediately after consolidation.57

Regarding vertical integration, many studies showing that quality does not improve (or gets worse) after vertical integration, while some analysis has shown modest improvements.58 One study of 15 integrated delivery networks finds no evidence that hospitals in these systems provide better clinical quality or safety scores than their competitors.59 Another study found that larger hospital-based provider groups had higher per beneficiary Medicare spending and higher readmission rates than smaller groups.60 However, one study looking at hospital quality measures from 2008 to 2015 found that vertical integration had a limited positive effect on a small subset of quality measures.61

Studies of markets where there has been horizontal consolidation largely have found that mergers do not improve quality, and that quality may actually be worse in highly concentrated markets than in markets with more competition. One study found that risk-adjusted one-year mortality for heart attacks in Medicare patients was 4.4% higher in more highly concentrated hospital markets compared to less concentrated markets.62 Another study that analyzed Medicare claims for patients treated for hypertension, a cardiac condition or an acute myocardial infarction found that patients in areas higher cardiology market concentration had worse health outcomes and higher health care expenditures.63

A study published in 2020 that followed hospitals for three years after a merger and compared those hospitals to a “control” group of hospitals that did not have a change in ownership found that the acquired hospitals’ outcome measures did not improve, when looking at scores for 30-day readmission and mortality rates among patients discharged from a hospital.64 That analysis also found that patient experience worsened slightly after a merger, as measured by patients’ responses to questions about whether they would recommend the hospital and whether doctors and nurses always communicated well. The one improvement noted in that study was in process measures, which improved in the years before the acquisition and so could not be conclusively attributed to a change in ownership. The American Hospital Association funded a study using a similar design to look at the impact of hospital mergers on inpatient quality that found “small improvements in quality for some quality measures.”65

Beyond health care quality, there have also been questions about the impact of hospital consolidation on the provision of charity care and other community benefits, and whether the impact differs depending on whether a hospital is for-profit or non-profit. A new study looking at this issue finds no evidence that non-profit hospitals provided more community benefits as their market share increased.66

The Coronavirus and Resulting Economic Crisis May Make More Providers Likely to Consolidate

The COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic crisis are leading to unprecedented financial pressure on health care providers. It is still unclear if this pressure will lead to more mergers or cause providers to close, but it is possible that the pace of consolidation will increase due to the economic impact of the pandemic. Health care spending dropped dramatically after the start of the coronavirus pandemic (Figure 2) due to delayed or forgone medical care.67 While spending started to pick up in May, it is not clear if that trend will continue given the record number of new COVID-19 cases in the subsequent months. This decrease in spending on health care services is leading to declines in provider revenue that could spur mergers, depending on the severity and duration of the revenue loss.

Figure 2

Compounding the impact of COVID-19, the current economic crisis could put additional financial pressure on some providers, particularly if the number of uninsured people rises. KFF has estimated that by early May 2020, nearly 27 million people were at risk of losing employer-sponsored coverage due to a job loss.68 About half of those individuals were estimated to be eligible for Medicaid and about 30% were estimated to be eligible for subsidized marketplace coverage.69 This shift from employer coverage to Medicaid alone will lead to lower revenues for providers, because employer-sponsored insurance tends to reimburse at much higher rates than Medicaid.70

The federal government has made different types of funding available to providers to help them weather the coronavirus pandemic. It is not yet clear if this infusion of funds is sufficient to help the providers most vulnerable to declines in revenue due to coronavirus and the ensuing economic fallout. If providers are not able to pay their bills, they may be financially motivated to merge with a larger system. Below we outline the three main sources of stimulus funding sources for providers.

- $175B in provider relief grants: The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act together allocated $175 billion for grants to providers to help cover expenses related to coronavirus and lost revenue due to the pandemic. About $118 billion in grants have already been allocated to providers, and a portion of the remaining money will be used to reimburse providers who treat uninsured COVID-19 patients.71 However, $50 billion of this fund was allocated to Medicare providers using a formula that gave more money to providers that tend to have higher margins.72 While these grants provide some assistance for providers, it is a small share of money compared to total hospital spending, which was $1.2 trillion in 2018.73

- $100B in advanced payments to Medicare providers: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services distributed about a $100 billion in advanced Medicare payments to providers.74 Most Medicare providers qualified for advanced payments representing three months of reimbursement from traditional Medicare in the period before coronavirus. About 80% of the advanced payments went to hospitals, with the remaining money going to physicians and other providers.75 Repayment for those advanced payments was scheduled to begin in August 2020, 120 days after payment was issued.76 However, providers are currently pushing for those loans to be forgiven, and Congress is also considering more favorable terms for repayment of the loans.77

- Treasury department and Small Business Administration loans: Along with other businesses and employers, health care providers are also potentially eligible for some of the loans included in the CARES Act and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act that the Treasury department, the Federal Reserve, and Small Business Administration are distributing. These loans include the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) for small businesses, which forgives loans if employers do not lay off workers and meet other criteria. According to a Treasury Department analysis, health care providers received 13% of the $520 billion in PPP loans that have been distributed to small businesses.78 While the CARES Act also appropriated $454 billion79 for loans to qualifying larger businesses—including hospitals and other large health care entities—there have been delays in distributing those loans.80 However, the Federal Reserve announced it is making changes to some of these loans so that it would be easier for non-profit institutions such as hospitals to qualify.81

Providers that accept any of these federal funds are not barred from future mergers, and most of this aid was not targeted to health care providers that may be most vulnerable to financial shocks from the coronavirus pandemic. Given that health care markets were consolidating even before the COVID-19 pandemic, aid to providers is unlikely to prevent health care markets from continuing to become more concentrated. However, it is possible that for some providers, this assistance may help stabilize their finances and increases the likelihood they can operate independently if that is their goal.

Discussion

There is now a large body of research showing that health care provider consolidation tends to raise prices without clear indications of quality improvements. Even before the pandemic, the U.S. health care system was becoming increasingly consolidated. The financial strains of the pandemic could increase the pace of consolidation among hospitals and physicians, which threatens to increase health care costs and premiums, without compelling evidence of commensurate quality improvements. Remedial action from policymakers could come in the form of increasing anti-trust enforcement—including taking steps to address any potential anti-competitive behavior in markets that are already consolidated—or targeted assistance to struggling providers that are trying to remain independent.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.