About the survey

Understanding how health insurance works involves exploring how people feel about their health coverage, how affordable that coverage is, how they interact with their insurance provider, the problems they experience, and, critically, how insurance works for people when they get sick. To accomplish this, the KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance interviewed a nationally representative sample of 3,605 U.S. adults with health insurance. To gauge the diversity of experience among insured adults, the sample includes interviews with 978 adults whose primary coverage is through their or a spouse’s employer, 885 adults with Medicare, 880 individuals who purchased their own coverage through the ACA Marketplace, and 815 adults with Medicaid. Importantly, people covered by different types of insurance have different levels of income, education and health status, which may affect their experiences and views. (See Appendix 1).

This initial report provides an overview of the survey findings, exploring problems patients often face when using their insurance –related to claims processing and denials, inadequate provider networks, and others – as well as whether consumers can resolve their insurance problems and the consequences that can arise from them. Along with problems insured adults have experienced, this report also covers how well consumers understand their health insurance, their rights, and the government agencies to call if they need help. In addition to an overview of the varied problems insured adults experience when using their insurance – especially for people who are sick – this report also provides a more detailed review of difficulty accessing mental health care and affordability concerns – two prominent issues among many insured adults. Finally, this report explores consumers’ views on public policies that might make insurance easier to understand and insurance problems easier to avoid or resolve. Data were analyzed across health status, coverage type, race and ethnicity and other consumer characteristics, and this report presents the findings where there were compelling differences.

In the coming months, KFF plans to release additional reports providing further detailed analysis on the insurance experiences of adults within specific types of insurance (employer coverage, Marketplace, Medicare, and Medicaid), on the experiences of key patient populations including those with specific chronic conditions, and about ongoing policy discussions to address health insurance problems, complexity, and affordability.

Key Findings

- Most insured adults give their health insurance positive ratings, though people in poorer health tend to give lower ratings. Most insured adults (81%) give their health insurance an overall rating of “excellent” or “good,” though ratings vary based on health status: 84% of people who describe their physical health status as at least “good” rate insurance positively, compared to 68% of people in “fair” or “poor” health. Ratings are positive across insurance types, though higher shares of adults on Medicare rate their insurance positively (91%) and somewhat lower shares of those with Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace coverage give their insurance a positive rating (73%).

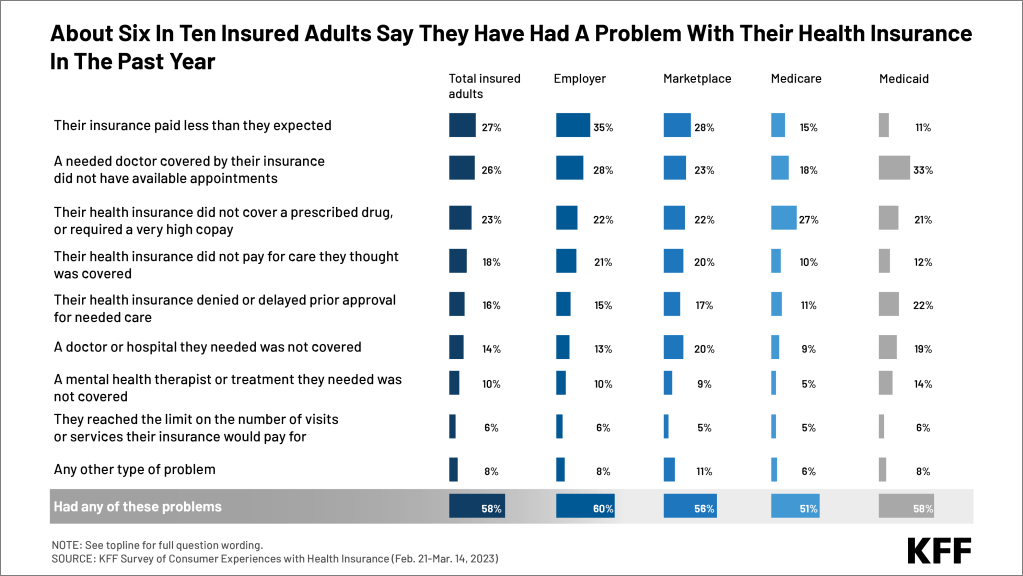

- Despite rating their insurance positively, most insured adults report experiencing problems using their health coverage; people in poorer health are more likely to report problems. A majority of insured adults (58%) say they have experienced a problem using their health insurance in the past 12 months – such as denied claims, provider network problems, and pre-authorization problems. Looking at responses by health status, two-thirds (67%) of adults in fair or poor health experienced problems with their insurance, compared to 56% of adults who say they are in at least “good” physical health. Notably, about three in four insured adults who received mental health care in the past year, or who use a lot of health care (defined as more than ten provider visits in a year) experienced insurance problems. At least half of adults across insurance types say they experienced a problem, though the nature of problems people experienced varied somewhat more based on their type of coverage.

- Nearly half of insured adults who had insurance problems were unable to satisfactorily resolve them, with some reporting serious consequences. Half of consumers with insurance problems say their problem was resolved to their satisfaction. Among the 58% of insured adults who had a problem with their insurance in the past year, about one in six (17%) say they were unable to receive recommended care as a direct result of their problems; 15% say they experienced a decline in their health and about three in ten (28%) say they paid more than they expected for care all as a direct result of their problems.

- Among those with the greatest mental health needs, many adults across insurance types find their coverage lacking and report forgoing needed care. Among insured adults who report being in “fair” or “poor” mental health, four in ten (43%) say there was a time in the past year when they did not get mental health services or medication they thought they needed, and a similar share (45%) give their insurance a negative rating when it comes to the availability of mental health providers. One in five of this group (19%) say there was a time in the past year when a particular mental health service or treatment they needed was not covered by their plan. People with Medicare – who are less likely overall to say they are in fair or poor mental health – are also somewhat less likely than adults with other types of insurance to say a needed mental health therapist or treatment was not covered by their insurance. Adults with Marketplace and Medicaid coverage are more likely than those with employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) or Medicare to negatively rate their insurance when it comes to the availability of mental health providers.

- Affordability of premiums and out-of-pocket costs are a concern, particularly for those with private health coverage, and for some, contributed to not getting care. About half of adults with Marketplace plans (55%) or ESI (46%) rate their insurance negatively when it comes to premiums, compared to 27% of people with Medicare and 10% of Medicaid enrollees. Four-in-ten insured adults say they skipped or delayed some type of care in the past year due to cost. One in six insured adults (16%), including larger shares of those at lower income levels, say they had problems paying medical bills in the past year.

- Insured adults overwhelmingly support public policies to make insurance simpler to understand and to help them avoid or resolve insurance problems. About nine in ten say they support requirements on insurers to maintain accurate and up-to-date provider directories, provide simpler, easier-to read EOBs, disclose their claims denial rates to regulators and the public, and provide in advance, upon request, information about whether care is covered and their out-of-pocket cost liability. Nearly eight in ten say they would be likely to use the services of a publicly established consumer assistance program (CAP) when they encounter insurance problems. All of these public policies have already been enacted, though not all have been fully implemented or funded. The survey did not probe trade-offs that might be involved in implementing existing or future consumer protections in these areas, such as administrative costs.

Consumers Generally Rate Their Health Insurance Positively, Less So When They Are Sick

Large majorities of insured adults across insurance types give their own health insurance an overall positive rating. But ratings vary, and the KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance finds that groups with greater health needs, who generally are more likely to use their health insurance to seek care, are also more likely to rate their health insurance negatively.

Insured adults who describe their physical health as either “fair” or “poor” are more likely to give their health insurance a negative rating, but the shares of those who describe their health this way also differ between insurance coverages. Across all coverage types, about one in six insured adults (16%) describe their physical health status as “fair” or “poor,” with larger shares of those with Medicaid (32%) and Medicare (23%) describing their physical health in this way.

Overall, about eight in ten (81%) insured adults rate the overall performance of their current health insurance as either “excellent” or “good,” including large majorities of those with ESI (80%), Marketplace coverage (73%), and Medicaid (83%). Adults with Medicare are the most positive in their overall ratings with nine in ten (91%) rating their coverage positively, including half who say it is “excellent.” (This brief reports on experiences of all people insured by Medicare combined, whether they are enrolled in traditional Medicare or private Medicare Advantage plans, and whether they are elderly or under age 65. In future briefs we will report in more detail on experiences of people with Medicare.)

Adults with “fair” or “poor” physical health are nearly twice as likely as those with at least “good” physical health to give their insurance a negative rating on its overall performance (31% vs. 16%).

Across each insurance type, insured adults with fair or poor health are more likely than their healthier counterparts to rate their insurance negatively. Notably, adults with fair or poor health with ESI coverage, Medicare, or Medicaid are more than twice as likely as their counterparts in at least “good” health to give their insurance an overall negative rating. Marketplace enrollees, regardless of health status, are the most likely to rate their insurance negatively.

Despite Positive Ratings, Most Adults Experience Problems Using Their Health Insurance

Though a majority of insured adults give positive ratings to their health insurance’s overall performance, most also report experiencing problems when they used their insurance in the past year. About six in ten (58%) insured adults report having experienced a problem with their health insurance in the past 12 months, including majorities of those with ESI (60%), Medicaid (58%) and Marketplace coverage (56%) and about half of adults with Medicare (51%).

Types Of Problems Vary By Type Of Insurance

Though large shares across insurance types report at least some problem with their insurance, the nature of problems people experience differs across health coverage types.

Claims payment issues – About a quarter (27%) of insured adults say there was a time in the past year when their health insurance paid less than they expected for a medical bill, and about one in six (18%) say there was a time when their insurance did not pay anything for care they received and thought would be covered. Smaller shares of adults with public health insurance coverage (Medicare 15%, Medicaid 11%) say their insurance paid less than they expected for a medical bill, compared to those with private coverage (ESI 35%, Marketplace 28%). Similarly, those with public coverage are less likely to report that insurance paid nothing at all for a service they thought was covered (Medicare 10%, Medicaid 12%) compared to those with private coverage (ESI 21%, Marketplace 20%).

Provider network issues – About a quarter (26%) of insured adults say there was a time in the past year when an in-network doctor they needed to see did not have available appointments and 14% say there was a time when a particular doctor or hospital they needed was not covered by their insurance. Generally, adults with Marketplace or Medicaid coverage are more likely than those with Medicare or ESI to report experiencing these provider network problems. Medicare Advantage plans typically establish limited networks of doctors and other providers, while traditional Medicare allows people to see any provider that accepts Medicare.

Pre-authorization issues – About one in six insured adults (16%) say their health insurance denied or delayed prior approval for needed care in the past 12 months. About one in five Medicaid enrollees (22%) experienced these pre-authorization problems whereas just one in ten of those with Medicare (11%) report experiencing this. While Medicare Advantage plans use prior authorization, traditional Medicare generally does not.

Prescription drug problems – About a quarter of insured adults (23%), including at least one in five across insurance types, say their insurance did not cover a needed prescription medication or charged a very high copay in the past 12 months. This prescription drug coverage problem is the most commonly experienced problem among people with Medicare (27%).

Problems with mental health coverage – One in ten adults say their insurance did not cover a particular mental health therapist or treatment they needed in the past year.

Adults In Poorer Physical Or Mental Health Are More Likely To Report Insurance Problems

Insured adults who report being in fair or poor physical health are more likely than those who describe their physical health as at least “good” to report having problems with their health insurance in the past year (67% vs. 56%). Similarly, insured adults who say they are in fair or poor mental health are more likely than those in at least “good” mental health to say they experienced a problem with their insurance (69% vs. 55%). Indeed, three in four (74%) insured adults who say they received mental health treatment in the past year report experiencing a problem with their insurance. Likewise, about three in four (78%) high utilizers of health care – those who had more than ten visits with a health care provider in the past year – say they experienced problems using their insurance.

Notably, differences in the share who experienced insurance problems between those in better and worse physical health persist across insurance types. For example, those in fair or poor health with ESI, Marketplace, or Medicaid coverage are more likely than their healthier counterparts with those insurance types to say that in the past year a doctor they needed to see did not have available appointments. Importantly, across insurance types, problems with prescription drug costs are more prevalent among insured adults in fair or poor health – who are often most likely to need access to prescription medication.

Nearly Half Who Experienced Insurance Problems Say They Were Not Resolved To Their Satisfaction

While half of insured adults who report experiencing an insurance-related problem in the past year say their biggest problem was resolved to their satisfaction, similar shares say it was either not resolved (19%) or resolved in a way they were unsatisfied with (28%). This was more often the case among consumers with Marketplace coverage; three in ten (31%) say their biggest problem was resolved, but not in the manner they would have liked, while one in four (25%) say the biggest problem they had with their insurance was not resolved. By contrast, a majority of those with Medicare (55%) or Medicaid coverage (55%) say their biggest problem was resolved to their satisfaction.

Among insured adults who had a problem with their health insurance in the past 12 months, most (78%) say they have taken some action to try and resolve the problem. Fifty-three percent say they contacted their insurance in an effort to resolve the problem, about half (49%) say they referred to their insurance website or documents for information and 45% say they contacted their doctor or medical provider or someone on their staff. About one in five insured adults who had a problem with their insurance say they asked family or friends for help (22%), while a similar share say they changed doctors (20%). One in ten say they filed a formal appeal. One in five insured adults who had a problem with their insurance say they took none of these actions in an effort to resolve the issue (22%).

Among Medicaid enrollees who had a problem with their insurance, 28% say they contacted their state Medicaid agency in order to resolve the problem. About one in five adults with ESI who had insurance problems say they asked someone in human resources at their employer for help (21%), while a smaller share of those with a Marketplace plan say they asked a Navigator or broker for help (11%). About one in ten people with Medicare with insurance problems contacted 1-800-Medicare or their State Health Insurance Assistance Program (12%).

Trying to fix a health insurance problem can be time consuming. Among adults who say their insurance problem has been resolved, either satisfactorily or not, 27% say it was resolved the same day it occurred, 25% say it took more than one day but less than one week, 31% spent one to four weeks, and 17% spent more than one month.

Among insured adults whose problems were not resolved, 12% say they were still trying and have been doing so for up to four weeks, and 35% are still trying and have been doing so for longer than one month. But 54% say they had given up and are no longer trying to fix it. Combined with the 22% of adults with problems who took no action at the outset, 31% of adults with insurance problems eventually give up on trying to resolve them.

Half Of Insured Adults Have At Least Some Difficulty Understanding Their Insurance

The KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance asked insured adults about how well they understand key aspects of their health insurance – what it covers, what they will owe out of pocket when they use care, how to find information about provider networks, what their explanation of benefits (EOB) statements say, and common terms used in health insurance such as “deductible.” Half (51%) of insured adults say they find at least one aspect of how their insurance works at least somewhat difficult to understand. Education level does not appear to help; a slightly higher share of college graduates (58%) said they had difficulty understanding an aspect of their insurance coverage. What people have difficulty understanding varies somewhat depending on their type of coverage, with people covered by private insurance through an employer or the Marketplace generally having more trouble comprehending their insurance than those enrolled in public coverage through Medicare or Medicaid.

What insurance covers – More than one-third (36%) of all insured adults say it is at least somewhat difficult for them to understand what their insurance will and will not cover. Larger shares of adults covered in Marketplace plans (46%) or ESI (40%) cite this difficulty.

Out-of-pocket costs – Thirty percent of insured adults overall say it is difficult for them to understand what they will owe out-of-pocket when they get health care, including larger shares of people with a Marketplace plan (41%) and about a third of adults with ESI (34%).

The Explanation of Benefits (EOB) – Three in ten insured adults – including 38% of those with Marketplace plans and 35% of those with ESI – say they find it difficult to understand statements explaining whether or how much insurance will pay for care; these statements are called Explanation of Benefits, or EOB.

Basic health insurance terminology – A quarter of all insured adults say they have difficulty understanding specific terms, such as “deductible,” “coinsurance,” “prior authorization,” or “allowed amount.” Among Marketplace enrollees, about one-third (32%) say they find these terms difficult to understand.

Provider networks – Nearly one in four insured adults (23%) say it is at least somewhat difficult for them to understand where to find information about which doctors and hospitals are covered in their health plan network. Adults covered by Marketplace plans (30%), Medicaid (27%), or by ESI (24%) are more likely than people with Medicare (15%) to cite this difficulty.

Notably, adults who say they experienced a problem with their insurance in the past 12 months are nearly twice as likely to as those who did not experience insurance problems to say it is difficult for them to understand at least some aspect of their health coverage asked about in the survey (63% vs. 33%).

Language barriers may also lead to difficulty understanding health insurance

Across race and ethnic groups, insured Hispanic adults (37%) are more likely than insured White (29%) and Black (24%) adults to report difficulty understanding their insurance EOB. The share who say they find it at least somewhat difficult to understand their EOB rises to 45% among adults who completed the survey in Spanish. Among these Spanish-dominant speakers, 35% say insurance documents are never or only sometimes available in a language they prefer.

Many Consumers Don’t Know Their Rights Or Where To Turn For Help

Four in ten insured adults (40%) know they have a legal right to appeal to a government agency or an independent medical expert if their health insurance refuses to cover medical services they think they need. A small share incorrectly believe they do not have appeal rights (9%), while about half (51%) say they are not sure. With the exception of people with Medicare, majorities across insurance types say they do not know or believe they do not have appeal rights if their insurance refuses to cover medical services they think are needed.

A majority of insured adults (76%) also say they don’t know which government agency to contact for help dealing with their insurance. Uncertainty over who to contact is particularly an issue among those with private health coverage with at least eight in ten adults with ESI (83%) or with a Marketplace plan (81%) saying they do not know which government agency to contact for help with insurance problems. About four in ten adults with Medicare and three in ten Medicaid enrollees say they do know which government agency to contact for help with insurance problems. For those who say they do know which government agency to contact, when asked to name the agency, few (2% of all insured adults with ESI or Marketplace coverage) name their state insurance department (the lead agency that regulates non-group insurance), and no one named the U.S. Department of Labor (the lead agency with jurisdiction over ESI).

Health Insurance Problems Can Have Financial And Health Consequences

The survey also finds that problems with health insurance can affect people’s ability to access medical care. Among insured adults who experienced a problem with their insurance in the past 12 months, 17% (10% of all insured adults) say that as a result of those problems they experienced a significant delay in receiving needed care, while a similar share (17%, or 10% of all insured) say they were unable to receive the recommended care at all. One in six (15%, or 9% of all insured) say they experienced a decline in health status as a direct result of their insurance problem. Notably, among those who had a problem with their insurance in the past year, about one in five (22%) adults with a Marketplace plan and one in four (26%) Medicaid enrollees say they were unable to get medical treatment recommended by a provider as a direct result of their health insurance problems.

Problems with health insurance can also lead to unexpected costs – 28% of insured adults who had a problem with their insurance (16% of all insured) say they ended up paying more for treatment or services than they expected as a direct result of those problems. Among those who had a problem with their health insurance, about one-third of adults with ESI (33%) or with Marketplace coverage (35%) say they ended up paying more than they expected as a direct result of those problems. Among those who paid more for treatment or services due to health insurance problems, 56% said the amount they had to pay as a result was less than $500, while 39% had to pay $500 or more.

Insurance Experiences of Consumers With Mental Health Needs

KFF’s Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance finds that many insured adults report problems accessing mental health care – including larger shares of those who say their mental health is “fair” or “poor” and are most in need of these services.

Many insured adults report problems with access to mental health services, including notable shares of adults who describe their mental health as either “fair” or “poor.” Younger adults, women, and Black and Hispanic insured adults disproportionately report being in fair or poor mental health, as do more than one in three Medicaid enrollees (36%), one in five Marketplace enrollees (20%), and 16% of those with ESI coverage. Adults with Medicare – most of whom are over the age of 65 – are less likely to report being in fair or poor mental health.

Additionally, about one in five (22%) insured adults say they have sought medical treatment or taken prescription medication for a mental health condition such as depression or anxiety in the past year, including about a third of Medicaid enrollees (35%) and nearly half of those who say their mental health is “fair” or “poor” (46%). Because of the eligibility pathways for Medicaid – including being disabled with a mental illness – it is not unexpected to see self-reported ratings for mental health and emotional well-being poorer than for other types of coverage.

Overall, about four in ten insured adults give their plans positive ratings for the availability of mental health providers covered and the quality of mental health providers available. About one in five insured adults (19%) rate their insurance negatively when it comes to the availability of mental health providers while about one in six (16%) give negative ratings when it comes to the quality of mental health. About four in ten insured adults say it doesn’t apply to them, presumably because they haven’t tried to access mental health services.

Given that many insured adults don’t attempt to access mental health services, it is useful to examine impressions of mental health coverage among those with greater mental health needs. When looking at those who describe their own mental health as “fair” or “poor,” we find much higher shares giving their insurance negative ratings for the quality and availability of mental health providers. Nearly half (45%) of insured adults who describe their own mental health as fair or poor give their plan a negative rating for the availability of mental health therapists and professionals, including a majority of those who have Marketplace coverage (56%). In addition, more than one-third (37%) of insured adults in fair or poor mental health give a negative rating to the quality of mental health providers available under their plan, including four in ten Medicaid enrollees (41%) and those with Marketplace coverage (41%).

When asked more specifically about seeking mental health care or treatment, one in ten insured adults say there was a time in the past twelve months when a particular mental health therapist or treatment they needed was not covered by their insurance – rising to one in five (19%) among those who rate their mental health as fair or poor – including similar shares of those with Medicaid (22%), ESI (19%), and Marketplace coverage (18%) and one in eight (13%) people with Medicare.

More broadly, among all insured adults, about one in six (17%) say that there was a time in the past year when they thought they might need mental health services or medication but didn’t get them. This includes one in four Medicaid enrollees (27%), one in seven insured adults with Marketplace coverage (18%) or ESI coverage (17%), and fewer than one in ten (7%) adults with Medicare.

Notably, at least four in ten insured adults (43%) who describe their mental health as either fair or poor say there was a time in the past year when they thought they might need mental health services or medication but didn’t get them for any reason, including more than four in ten of those with ESI (46%), Marketplace (45%), and Medicaid coverage (44%). Medicare beneficiaries with fair or poor mental health are somewhat less likely to report forgoing needed mental health care (27%).

About a third (31%) of insured adults under age 30, and about a quarter (23%) of those ages 30 to 49 say there was a time in the past 12 months when they thought they might need mental health care but did not get it, whereas just one in ten adults between the ages of 50 and 64 say the same. Even among insured adults who describe their mental health as “fair” or “poor”, those between the ages of 50 and 64 are less likely than adults under the age of 30 to say there was a time in the past year when they needed mental health care but did not get it (32% vs. 55%). Insured Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say they experienced this problem (21% vs. 15%) and women are nearly twice as likely as men to say they experienced this (21% vs 11%).

There are many reasons insured adults cite for going without needed mental health services or medication: just under half (47%) of those who skipped such care say they were too busy or could not get time off work or school, 44% say they couldn’t find a provider they trust, 36% say they didn’t know how to find care, and 34% say they were afraid or embarrassed to seek care. But insurance was a factor for many. More than four in ten said they didn’t get needed mental health care because they couldn’t afford the cost (44%) or find a provider that was easy for them to get to for an in-person visit (42%). Just over a third of those who didn’t get mental health care say it was because their insurance wouldn’t cover it (37%).

Affordability Concerns with Health Insurance

Most insured adults rate their health insurance as “excellent” or “good” when it comes to their prescription co-pays (61%), their monthly premiums (54%) and the amount they have to pay out of pocket to see a doctor (53%). Yet, at least a third rate their insurance as “fair” or “poor” on each of these metrics, and affordability ratings vary depending on the type of coverage people have.

About half of those with ESI and Marketplace coverage rate their plan as either “fair” or “poor” when it comes to their monthly premium (46% and 55%, respectively), and the amount they have to pay out of pocket to see a doctor (50% and 55%, respectively). About a third (35%) of those with ESI and four in ten (43%) of those with Marketplace coverage give a negative rating to their prescription co-pays. About one in four adults with Medicare give negative ratings to the amount they have to pay each month for insurance and to their out-of-pocket prescription costs, while about one in five give their insurance a negative rating when it comes to their out-of-pocket costs to see a doctor.

Smaller shares of Medicaid enrollees give negative ratings to these dimensions of their health insurance. Medicaid does not charge monthly premiums in most states, and copays for covered services, where applied, are required to be nominal.

One In Six Insured Adults Report Problems Paying Medical Bills, Including One-Third Of Those In Fair Or Poor Health

Overall, one in six insured adults (16%) say they have had problems paying or an inability to pay for medical bills in the past year, including similar shares of adults with Marketplace coverage (19%), ESI (17%), and Medicaid (16%). Adults with Medicare are less likely than those with Marketplace coverage or ESI to report issues affording medical bills in the past year (12%).

Lower-income adults in general are more likely than those with higher incomes to report difficulty paying medical bills. For insured adults with annual household incomes below 138% of the federal poverty level ($20,120 for a single person, $34,307 for a family of 3) – the eligibility threshold to qualify for Medicaid in those states that have expanded the program under the ACA — about a quarter (23%) say they had problems paying medical bills in the past year, as do a similar share of those with household incomes between 138% and 199% FPL (22%). Comparably, just under one in ten (8%) adults with incomes over 400% FPL say they have had problems paying or an inability to pay for medical bills in the past 12 months.

Additionally, insured adults who describe their physical health as either “fair” or “poor” are more than twice as likely as those with at least “good” physical health to say they have had problems paying medical bills in the past year. Insured women are more likely than men to report problems paying medical bills (20% vs. 11%), and Black adults are more likely than White adults to report problems paying or an inability to pay medical bills (23% vs. 14%).

Problems paying medical bills are particularly notable among lower-income adults with private plans. For those with household incomes below 200% FPL, three in ten adults with ESI (31%) and a quarter of adults with Marketplace plans (24%) say they have had problems paying medical bills in the past year.

Among the 16% of insured adults who had problems paying or an inability to pay medical bills in the past year, nearly eight in ten (77%, or 12% of all insured adults) cite the cost of copays or deductibles being more than they could afford as a reason they had problems paying these bills. Among the other reasons cited, about six in ten (57%, 9% of all insured) say the bill was for care or services that their insurance didn’t cover, just under half (46%, 7% of all insured) say they received care from an out-of-network doctor or facility and their insurance either didn’t cover it or only covered a portion, and four in ten (39%, 6% of all insured adults) say they submitted a claim to their insurance but the claim was denied.

Four In Ten Insured Adults Face Cost Barriers To Care

Overall, 41% of insured adults say they have delayed or gone without some form of medical, dental, vision, or hearing care due to cost in the past 12 months. About one in six insured adults (14%) say they have delayed or gone without a visit to a doctor’s office in the past year because of the cost, including similar shares of those with ESI (17%) and Marketplace coverage (18%). Smaller shares among those with Medicaid (10%) and Medicare (5%) report skipping or delaying a doctor’s visit due to cost in the past year. At least one in ten across insurance types report delaying or not filling a prescription due to cost.

Certain other health care services such as dental, vision, or hearing care are often not included as part of health insurance coverage. Across coverage types, at least one in four report cost barriers to accessing dental care in the past year, including about four in ten of those with Medicaid (39%) and Marketplace coverage (37%) and a quarter of those with ESI (25%) and Medicare (26%). Smaller but still important shares report delaying or going without hearing or vision care due to costs.

In total, about four in ten insured adults say they have delayed or gone without a visit to the doctor’s office, vision services, hearing services, prescription drugs or dental care within the last year because of the cost, including half of those with Marketplace coverage and half of Medicaid enrollees. Delayed or skipped care could be due to the cost of having to pay for the deductibles or copays, or the out-of-pocket cost for care not covered by insurance at all.

Most Insured Adults Support Public Policies To Make Insurance Work Better for People

The KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance asked about several public policies that might help people avoid insurance problems or resolve them more easily and found broad support for each, including large majorities across insurance types and across partisans. The survey did not probe trade-offs that might be involved in changing how measures like these are implemented, including additional administrative costs.

Simple, easy-to-read EOBs – Nearly all insured adults (94%) support requiring health insurance statements (explanations of benefits, known as EOBs) to be written in simple, easy-to-read language that explains the reasons for coverage decisions and how to appeal if one disagrees. Federal law has long required that EOBs for private health plans be written “in a manner calculated to be understood by the claimant.” Medicare Advantage plans and Medicare Part D plans and Medicaid managed care plans also are required to provide EOBs that are easily understandable to enrollees.

Accurate provider network directories – About nine in ten insured adults also support government policy to require health insurers to provide accurate and up-to-date information about who is in their network. In 2021, Congress passed a law applying this requirement to private health plans, though this requirement has not yet been implemented. Medicare and Medicaid both require private health plans delivering these benefits to provide consumers with accurate information about their provider networks. Extensive provider directory inaccuracy problems have been documented across the coverage types. This year CMS issued a new proposed regulation that would establish national appointment wait time standards and require states to use secret shopper surveys to determine the accuracy of provider directory information in Medicaid managed care plans

Advanced EOB – Nine in ten insured adults also support requiring health insurance companies to tell people in advance (upon request) if a service they need is covered and, if so, how much they would be required to pay out-of-pocket. In 2021, Congress passed a law applying this requirement to private health plans, though this requirement has not yet been implemented.

Disclosure of claims denial rates – More than eight in ten (85%) insured adults support a requirement for health insurance to tell regulators how often they deny claims and to disclose that denial rate to consumers. Though this disclosure is required by the Affordable Care Act, this requirement remains largely unimplemented. The Inspector General has recommended that Medicare Advantage plans be required to definitively identify and report on denials. Federal rules require states to have systems in place to conduct oversight of Medicaid managed care plans generally, but do not require data reporting on claims denials.

Consumer Assistance/ombudsman programs – Additionally, the survey also described free consumer assistance programs (CAPs) – operating in some states to help people file appeals and resolve problems with their health insurance – and asked how likely insured adults would be to use this type of program. Nearly eight in ten said they would be very (36%) or somewhat (43%) likely to use such a program. Notably, close to half of Black (46%) and Hispanic (45%) insured adults say they would be very likely to use a CAP program. Federal law authorized the establishment of these programs in every state, but Congress has not provided funding for CAPs since 2010 and some that were initially established have since closed. Where such programs do exist, consumers appear to be largely unaware of them. Only 3% of consumers who reported having insurance problems in the past year said they contacted a CAP for help.

Discussion

In the U.S., health insurance is the way people generally get access to health care. Having coverage is valuable to people, and so not surprisingly, most who have it rate it favorably overall. But we don’t buy health insurance in case we stay healthy, so monitoring how coverage works for people who are sick is particularly important in gauging how well our health insurance system works when people need it the most. The KFF Survey of Consumer Experiences with Health Insurance finds that most consumers experience problems when they try to use their coverage – related to denied or mishandled claims, provider network issues, pre-authorization requirements and others. Among high utilizers of health care, and people who use mental health care, about three in four people experience problems with their insurance.

The types of problems people experience vary depending on the type of coverage they have. For example, people in Marketplace and Medicaid are more likely to experience provider network problems compared to people with traditional Medicare. People with Marketplace and ESI coverage more often experience claims denials than people with public coverage, though Medicaid enrollees report problems with pre-authorization denials more often than consumers with any other type of coverage. In addition, affordability of health insurance premiums and out-of-pocket costs is a particular concern for people with private (ESI and Marketplace) coverage. In follow up reports, we will delve deeper into experiences of consumers, especially those with serious and chronic health conditions, by coverage and problem type.

Challenges using health insurance are particularly acute for those who describe their mental health as “fair” or “poor,” with 45% rating their coverage negatively for the availability of mental health providers. Also, a sizable share (37%) of this population, who said that they did not get needed mental health care in the last year, say it was because their insurance did not cover the care. At a time when most US adults say mental health is a crisis in the U.S., such insurance barriers to mental health care are cause for concern.

We also find most consumers struggle to understand their health insurance – many have difficulty understanding what their insurance covers, what they’ll owe out of pocket, how to find information on network providers, and what their EOB says. This is not merely a matter of education as large shares of insured adults with college degrees also report difficulty understanding aspects of their insurance.

People who encounter problems using their insurance often can’t fix them. About half of consumers with problems said they were able to resolve the problem to their satisfaction. One in six consumers who experienced health insurance problems in the past year said they were not able to access recommended care as a direct result; one in six also said their health status declined as a direct result; and about one in four said they ended up paying more out of pocket for care. Most consumers (60%) don’t understand they have legal rights when problems arise, and most (76%) do not know what government agency to call if they need help.

Over the years, Congress has enacted a number of measures to make health insurance more understandable and easier to navigate, and to hold health insurers and public programs accountable for the coverage they promise. These measures, not surprisingly, attract broad support among the public. How government administers these protections, including those that are yet to be implemented, is a key consideration. Alone, these measures are unlikely to eliminate all the problems people encounter with health insurance, especially those related to affordability, but they may help to reduce somewhat the dizzying complexity of health insurance in the U.S. And they may inform oversight so that regulators can better monitor how well insurance works when people need to use it. At the same time, stronger oversight and accountability could entail more administrative costs – a trade-off we did not probe in this survey.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The views and analysis contained here do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.