As a candidate in 2020, President Biden campaigned on building upon the Affordable Care Act (ACA) by increasing the amount of financial assistance available to people buying their own health insurance coverage through the ACA Marketplaces. Temporary subsidies were originally passed as part of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in 2021, which included two years of enhanced subsidies (2021 and 2022). The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which passed in 2022, extended these enhanced subsidies for an additional three years, ending after 2025.

The IRA and ARPA’s enhanced health insurance subsidies both increase the amount of financial help available to those already eligible for assistance under the ACA and also newly expand subsidies to middle-income people (with incomes over four times the poverty level, $103,280 for a family of three in 2024), many of whom were previously priced out of coverage. These subsidies, combined with increased funding for outreach and marketing, have led to record-high enrollment in the ACA Marketplaces.

By the time these enhanced subsidies are currently set to expire at the end of next year, they will have been an integral part of the ACA Marketplaces for 5 years, or nearly half as long as the ACA Marketplaces have existed. Millions of enrollees have come to rely on the enhanced subsidies, with more people gaining Marketplace coverage since President Biden took office than had signed up for ACA Marketplace when the markets first launched in 2014. If the enhanced subsidies expire, almost all ACA Marketplace enrollees will experience steep increases in premium payments in 2026. However, the subsidies come at a steep cost to taxpayers, with the CBO projecting that a permanent extension of the subsidies would cost $335 billion over the next ten years.

The charts below show the impact these subsidies have had on enrollment and premium payments, and the potential implications if the enhanced subsidies expire. This analysis finds that:

- The recent growth in ACA Marketplace plan enrollment has been driven primarily by low-income people, with signups by people with incomes up to 2.5 times poverty growing 115% since 2020.

- Enhanced subsidies have cut premium payments by an estimated 44% ($705 annually) for enrollees receiving premium tax credits. If the subsidies expire, most Marketplace enrollees will see premium payment increase substantially.

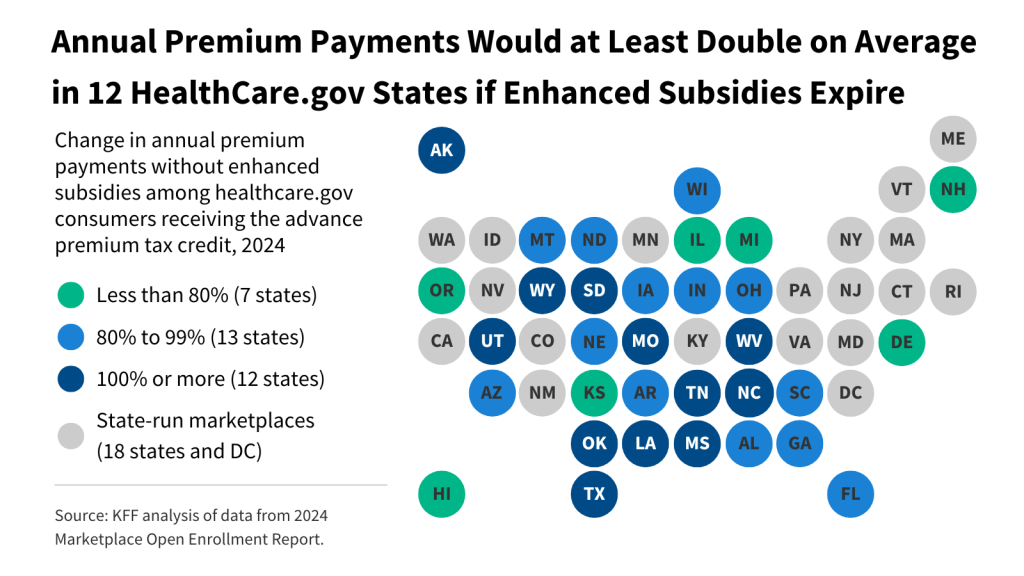

- Without these enhanced subsidies, premiums would double or more, on average, for subsidized enrollees in 12 states using Healthcare.gov.

While enhanced subsidies expire at the end of 2025, insurers and regulators will want to know well in advance whether the subsidies will be renewed or discontinued so they can set accurate premiums for 2026.

Since 2020, the year before the enhanced subsidies went into effect, the number of people with ACA Marketplace coverage has grown by 88% from 11.4 million to 21.4 million.

All the growth in Marketplace enrollment in the last four years is among people receiving an advanced payment of the premium tax credit. Subsidized enrollment is up 106%, from 9.6 million (84% of Marketplace enrollees) in 2020 to 19.7 million people (92% of the total number of Marketplace enrollees). If the Inflation Reduction Act’s enhanced subsidies expire, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects ACA Marketplace enrollment to drop sharply from an estimated 22.8 million in 2025 to 18.9 million the following year. CBO projects that enrollment would continue to fall in the subsequent years reaching as low as 15.4 million in 2030.

Spurred by the availability of plans with no or very low premium payment – often with very low deductibles – made possible by enhanced subsidies, low-income enrollees (those with incomes up to 2.5 times the federal poverty level) have driven most (83%) of the enrollment growth in the ACA Marketplaces from 2020 to 2024. While these plans with little or no premium payment are available nationwide, they are available to a larger share of ACA Marketplace enrollees in the ten states that have not expanded Medicaid.

While most of the recent growth in enrollment is from low-income enrollees, all income groups have seen substantial growth. From 2020 to 2024, the number of Marketplace enrollees with incomes up to 2.5 times poverty grew by 115%, whereas enrollment for those with incomes between 2.5 and 4 times poverty grew by 36%, and enrollment for those with incomes above 4 times poverty grew by 57%.

ACA Marketplace enrollees with incomes just above the federal poverty level (up to 2.5 times poverty) are eligible for cost sharing reductions (CSR) that reduce deductibles and other cost sharing. From 2020 to 2024, the number of enrollees receiving cost sharing reductions increased by 91% from 5.6 million to 10.6 million enrollees.

The Inflation Reduction Act’s enhanced subsidies make the reduced cost sharing plans more affordable. For example, $0 premium silver plans with very low deductibles are available to the lowest income enrollees (those with incomes up to 1.5 times poverty), whereas before the enhanced subsidies became available, these enrollees would have had to pay about 2%-4% of their household income for a plan with a reduced deductible.

The enhanced subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act reduce net premium costs by 44%, on average, for enrollees receiving premium tax credits, though the amount of savings varies by person. In 2024, the average annual premium payment would have been $1,593, but instead was $888 because of the Inflation Reduction Act subsidies, which average $705 per enrollee.

On average, the total annual premium is similar in 2024 ($7,320) to what it was in 2020 ($7,132), but the federal government is paying a larger share of the total premium (a subsidy of $6,432 or 88% of the average annual premium in 2024, compared to a subsidy of $5,942 dollars or 83% of the average annual premium in 2020).

Enhanced subsidies work by reducing the amount an enrollee has to pay for a benchmark silver plan. Under the Inflation Reduction Act, the amount of money enrollees are required to contribute toward their monthly silver premium varies by income, on a sliding scale with lower income enrollees paying as little as $0 and higher income enrollees paying as much as 8.5% of their household income.

Without enhanced subsidies, an enrollee making just above poverty would be required to pay around 2% of their income for a benchmark silver plan. With enhanced subsidies, however, most enrollees with incomes around the poverty level are eligible for zero-dollar benchmark silver plans. Similarly, without enhanced subsidies, an enrollee with an income just above 400% of the poverty level would have to pay full price for their monthly premium (because they would be ineligible for financial assistance), but with the enhanced subsidies, they pay no more than 8.5% of their household income.

The chart above depicts the percent increase in premium payments for a 45-year-old buying a silver plan, if enhanced subsidies were to expire. (Because 2025 premiums and federal poverty guidelines are not yet available, the chart is based on 2024 premiums and poverty guidelines.)

Low-income enrollees would experience the steepest percent increase in their annual premium payments if enhanced subsidies were unavailable. A 45-year old enrollee making $25,000 (166% of poverty) would see their annual premium payments grow by an average of 573%, or $917, for a benchmark silver plan (an increase from $160 for the annual premium payment with enhanced subsidies to $1,077 without enhanced subsidies). Prior to the enhanced subsidies, enrollees making above 400% of poverty were ineligible for premium assistance. Without enhanced subsidies, a 45-year old individual making $65,000 (432% of poverty) would experience a premium increase of $941 annually from $5,525 to $6,466 (the full cost of the benchmark silver premium).

Prior to the ARPA and Inflation Reduction Act, individuals making above 400% of poverty were ineligible for ACA Marketplace premium subsidies and had to pay the full cost of monthly health insurance premiums. In 2024, CMS estimates that individuals making above four times poverty in HealthCare.gov states save an average of $4,248 annually due to the Inflation Reduction Act’s enhanced subsidies. Without the Inflation Reduction Act subsidies, middle income ACA Marketplace enrollees with incomes just above four times poverty would, in many cases, be priced out of health insurance coverage. The number of ACA Marketplace enrollees making above four times of poverty quadrupled from approximately 400 thousand in 2021 to 1.5 million in 2024.

Inflation Reduction Act subsidies are available nationwide, but current data on the amount of the enhanced subsidies are only available in the 32 states that use Healthcare.gov. In these states, 15.5 million people are receiving an average of $624 per year in enhanced subsidies because of the Inflation Reduction Act. On an annual basis, this translates to nearly $10 billion in enhanced Inflation Reduction Act subsidies going to enrollees in these 32 states in 2024. Among states using Healthcare.gov, the majority (52%) of this federal funding is going to enrollees in Florida ($2.2 billion, or 22%), Texas ($1.5 billion, or 16%), Georgia and North Carolina ($660 million, or 7%, each). These are all high-population states, but also stand out because most have not expanded Medicaid, and therefore have more low-income residents who qualify for substantial ACA subsidies.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that making enhanced subsidies permanent would result in an increase of $275 billion in direct outlays and a reduction in revenues of $60 billion, for a net impact of $335 billion on the federal budget over the 10-year period from 2025 to 2034. This amount reflects higher enrollment induced by the enhanced subsidies and projections of premium growth over time.

If the Inflation Reduction Act’s enhanced subsidies expire, the vast majority of ACA Marketplace enrollees will see their premium payments increase significantly in 2026.

The results of the 2024 elections will likely play a major role in whether enhanced subsidies are extended beyond 2025. The map above shows 2024 ACA Marketplace enrollment by congressional district in the 118th Congress. (Though some states have redrawn their congressional district lines ahead of the 2024 election for the 119th Congress, they remain the same for the majority of states as in the 2022 elections for the 118th Congress).

Generally, enrollment in Marketplace coverage by congressional district is largest in the South. At least 10% of the population is enrolled in ACA Marketplace plans throughout all congressional districts in Florida and South Carolina, along with most in Texas, Georgia, and Utah. In Florida, there are nine congressional districts where at least 20% of the population is enrolled in in a Marketplace plan.

If the Inflation Reduction Act’s enhanced subsidies were to expire at the end of next year, the vast majority of ACA Marketplace enrollees would see significant increases in their premium payments. However, these increases would vary by state because of differences in the incomes and ages of people living in each state, as well as differences in the premiums charged by insurers in each state.

For subsidized enrollees in states using Healthcare.gov, premium payments average about $672 per year in 2024 ($56 per month). Without enhanced subsidies, the average annual premium payment would rise by 93% ($624) to $1,296.

Based on 2024 premiums, if these enhanced premium subsidies were to expire, subsidized Marketplace enrollees in at least 12 states would see their annual premium payments double or more, on average. As these data are only available in states using Healthcare.gov, there could be additional states that would see average premium payments double. Among states using Healthcare.gov, average annual premium payments for subsidized enrollees would grow the most in Wyoming (195%, or $1,872), Alaska (125%, or $1,836), and West Virginia (133%, or $1,404). In Texas, annual premium payments would increase by an average of 115%, or $456, for the 3.4 million people receiving premium tax credits, if these subsidies were to expire.

If enhanced subsidies expire, gains in Marketplace enrollment are projected to reverse and the health status of remaining enrollees may be sicker, on average, than it is with enhanced subsidies. If insurers expect to lose their healthier enrollees, they may raise premiums heading into 2026.

Every year, in early spring, insurers compile and then submit detailed rate filings proposing premium changes for the following year, for review by state regulators. Regulators evaluate insurer justifications for premium increases, provide feedback to the insurers, and request revisions or additional justifications as deemed necessary. This process stretches into the summer each year.

For the 2026 plan year, when the Inflation Reduction Act subsidies are set to expire, insurers will have to submit their proposed premiums and justifications in early 2025 and finalize their premiums by August 2025, in advance of the 2026 open enrollment period beginning November 1, 2025.

Because of this lengthy process, insurers and state and federal regulators will want to know whether enhanced subsidies will expire or be renewed well in advance of their expiration or renewal. In the leadup to the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, uncertainty over whether the enhanced subsidies would be extended led some insurers to increase premiums. An April 2022 letter to Congress from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners and signed by regulators from Idaho, Missouri, Connecticut, and North Dakota urged Congress to “to act by July of this year to extend the enhanced premium tax credits beyond their current end date,” which, at the time, was the end of 2022.

Methods

Enrollee counts by income group for Figures 2 and 6 were taken or calculated from the CMS Open Enrollment period State-Level Public Use Files (PUFs) or the 2021 Open Enrollment report. Starting in 2022, enrollee counts in the State-Level PUF for individuals making below 100% and above 400% of poverty became available. In prior years, enrollee counts in the state-level PUF for people making below 100% of poverty, above 400% of poverty, or with unknown income were typically grouped together. For Figure 2, due to data limitations, enrollees with unknown incomes or making below 100% FPL are included in the “Above 400% FPL” category in 2018-2020. Individuals making below 100% FPL make up around 2% of total ACA Marketplace plan selections in 2024.

In Figure 2, the number of enrollees making below 100% of poverty in 2021 was approximated by multiplying the share of enrollees making below poverty level during the 2021 Open Enrollment period (found in the 2024 Open Enrollment report) by the 2021 national plan selection total. In Figure 2, the number of enrollees making above 400% of poverty for 2021 includes the number of consumers with other/unknown income subtracted by the approximated number of enrollees making below poverty. In Figure 2, due to unavailability of some states’ data, plan selections by income category in 2018-2021 do not sum to total national plan selections. In Figure 2, enrollees with other or unknown incomes (due to them not requesting financial assistance) are included in the “Above 400% FPL” category in 2022-2024.

2024 county-level plan selections were collected from a combination of the 2024 County-Level Public Use File from CMS, state open enrollment summary reports, or estimated by determining the share of plan selections by county for a given state in a prior year and applying this to the total state plan selection value from the CMS 2024 OEP State-Level Public Use File.

2024 plan selections were mapped onto the 118th Congressional District boundaries. To map county-level plan selections to the congressional district level, the Missouri Census Data Center Geocorr 2022 tool was used. For counties that corresponded to multiple congressional districts, an allocation factor was used to apportion plan selection enrollment. The vast majority of states will use the same Congressional District lines in the 2024 election for the 119th Congress as in 2022 for the 118th Congress. Some states have finalized changes to their Congressional District lines for the 2024 election while others are currently in litigation.

Mollyann Brodie

Mollyann Brodie  Liz Hamel

Liz Hamel  Ashley Kirzinger

Ashley Kirzinger

Irving Washington

Irving Washington  Hagere Yilma

Hagere Yilma