Comparing Trump and Biden on COVID-19

Issue Brief

Introduction

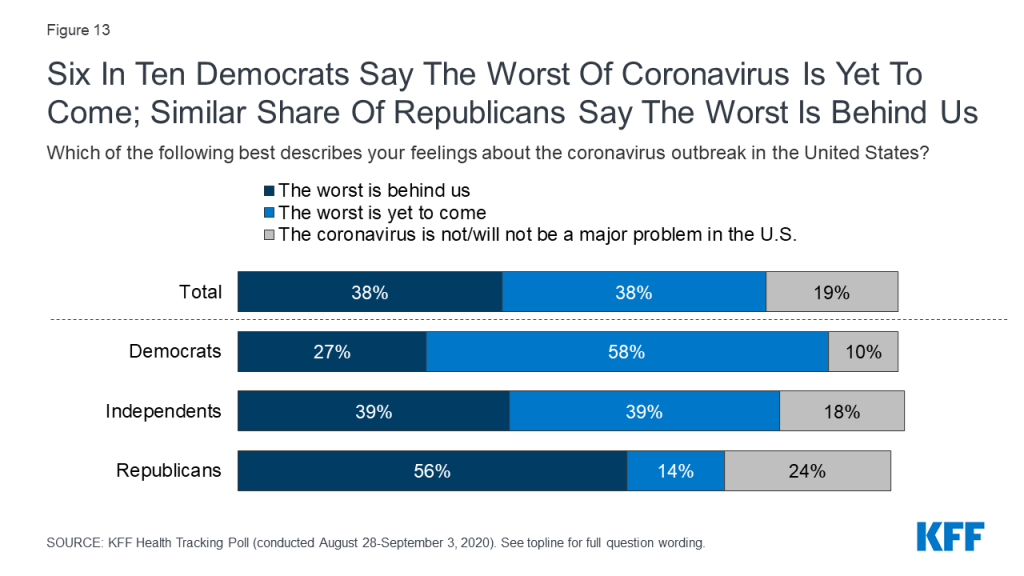

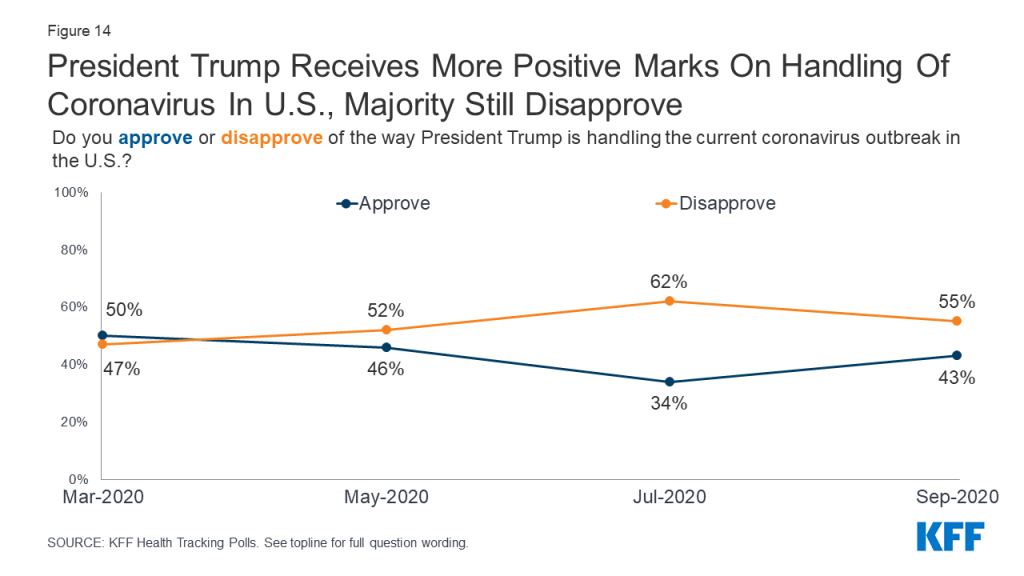

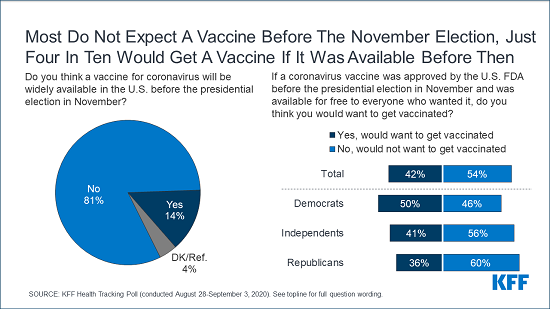

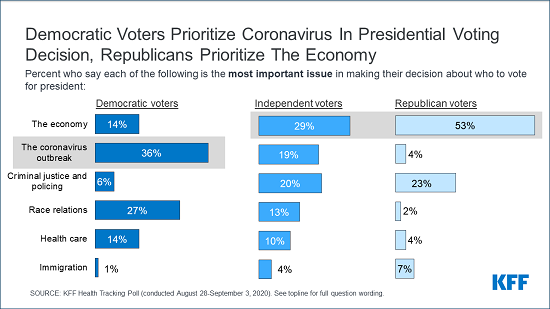

The first cases of a novel coronavirus were reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) in early January. Since then, the COVID-19 pandemic has become the worst health crisis facing the global community in more than a century. It has also taken a particular toll on the United States. Although the U.S. only represents 4% of the global population, as of early September, it accounts for 23% of all COVID-19 cases and 21% of all deaths, and ranks number one among high-income countries as measured by cases per capita. In addition, most states in the U.S. are considered “hotspots”, with ongoing, widespread community transmission; shortages of testing and other needed supplies also continue. COVID-19 has significantly affected daily life in America, including the economy and school closures, and has emerged as an important factor in the 2020 Presidential election. Polling data indicate that a majority of voters disapprove of President Trump’s handling of the outbreak and prefer Democratic candidate Joe Biden when it comes to tackling the pandemic. To gain a better understanding of how the candidates differ on their approach to addressing COVID-19, this document compares Trump’s record with Biden’s proposals. It starts with a broad overview of each candidate’s approach, followed by a detailed, side-by-side comparison.

Donald Trump

To date, in place of a coordinated, national plan to scale-up and implement public health measures to control the spread of coronavirus, the Trump Administration has chosen to rest the main responsibility for the COVID-19 response with the states, with the federal government serving as “back-up” and “supplier of last resort.” While this in part reflects federalism and the decentralized nature of U.S. public health, the lack of a national plan and strong federal guidelines have significantly contributed to a patchwork of policies, supplies, and outbreak trajectories across the country, and worsening community spread.

Early on, the President’s initial response to the new outbreak was focused on sealing U.S. borders and preventing entry of the virus. President Trump moved to suspend entry from China on January 31, followed by others since. However, with community transmission already underway in the U.S., and challenges with screening arriving passengers, travel restrictions were not effective in curtailing spread in the U.S. Meanwhile, the federal government was slow in bolstering public health capacities, such as testing and contact tracing, at the time the virus began to circulate domestically. As cases and deaths escalated, the gulf between what was needed and what was available grew quickly.

By mid-March, facing growing case numbers and seeing what had happened in other countries, several U.S. state and local jurisdictions began implementing stay-at-home orders and other social distancing policies. After conflicting messages from the President, who minimized the threat of the virus, the White House issued federal social distancing guidelines on March 16 for a 15-day period. Soon after, the President began pushing toward reopening, tweeting on March 22, for example, that “We cannot let the cure be worse than the problem itself. At the end of the 15 day period, we will make a decision as to which way we want to go!” and saying he hoped the country would reopen by Easter, with “packed churches.” The White House extended the social distancing period through the end of April, and issued reopening guidelines for states on April 16. Still, even before the end of April, the President began encouraging Governors to reopen, although key reopening metrics were not yet met in most places. The President has also pushed for schools to re-open in-person even though community transmission has remained high in many places, and is much higher than it was in other countries that moved to re-open in-person schooling.

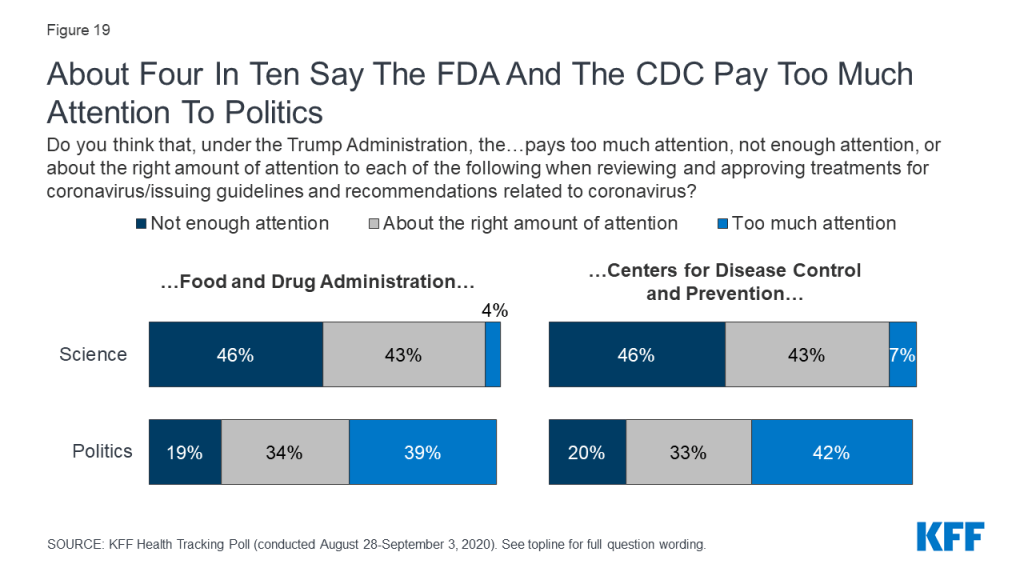

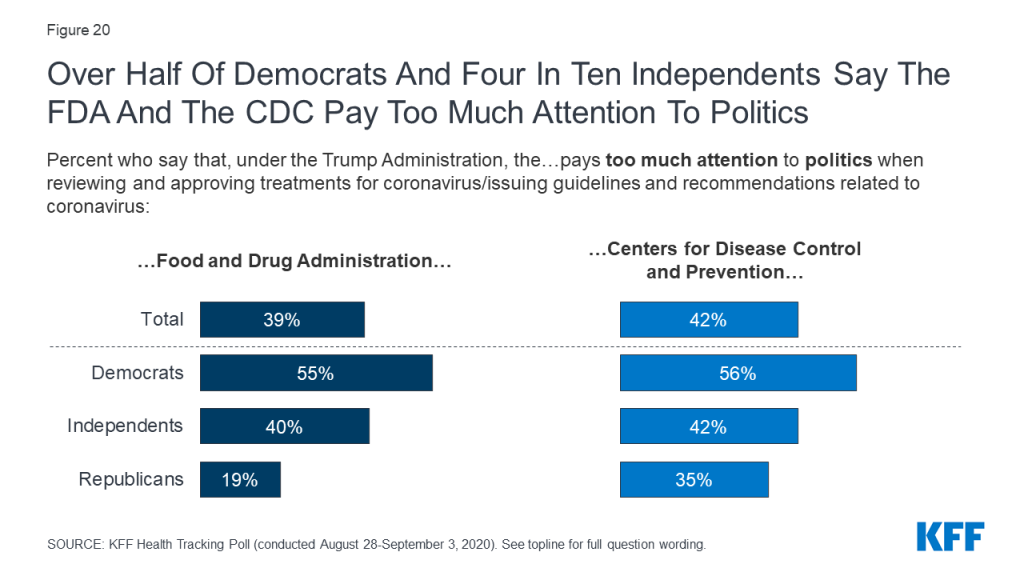

There have been ongoing challenges with COVID-19 testing in particular. These started with an early, faulty test developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that resulted in a significant delay in scaling-up testing as coronavirus spread quickly in the U.S. They have continued through to the present with ongoing shortages of critical testing supplies; significant delays in turn-around times for results; and shifting and sometimes confusing federal guidelines that have been reported to be subject to political pressure. Yet the President said in March that “Anybody that wants a test can get a test,” and in May, “As far as Americans getting a test, they should all be able to get a test right now.” More recently, while Administration officials have continued to say that anyone who needs a test could get one, they have acknowledged the need to reduce turn-around times and continue to work to increase testing capacity.

Throughout the pandemic, and even as cases and deaths increased, the President has downplayed the threat of COVID-19. For example:

- On January 22, in response to a question about whether he was worried given the first report of known U.S. case, he said, “No. Not at all. And– we’re– we have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s—going to be just fine.”

- On February 2, “We pretty much shut it down coming in from China.”

- On February 25, “We have very few people with it.”

- On April 28, “But I think what happens is it’s going to go away. This is going to go away.”

- On June 17, he said it was “fading away.”

- On July 19, “I think we’re gonna be very good with the coronavirus. I think that at some point that’s going to sort of just disappear. I hope.”

- On August 5, “It’s going away. Like things go away. No question in my mind that it will go away, hopefully sooner rather than later.”

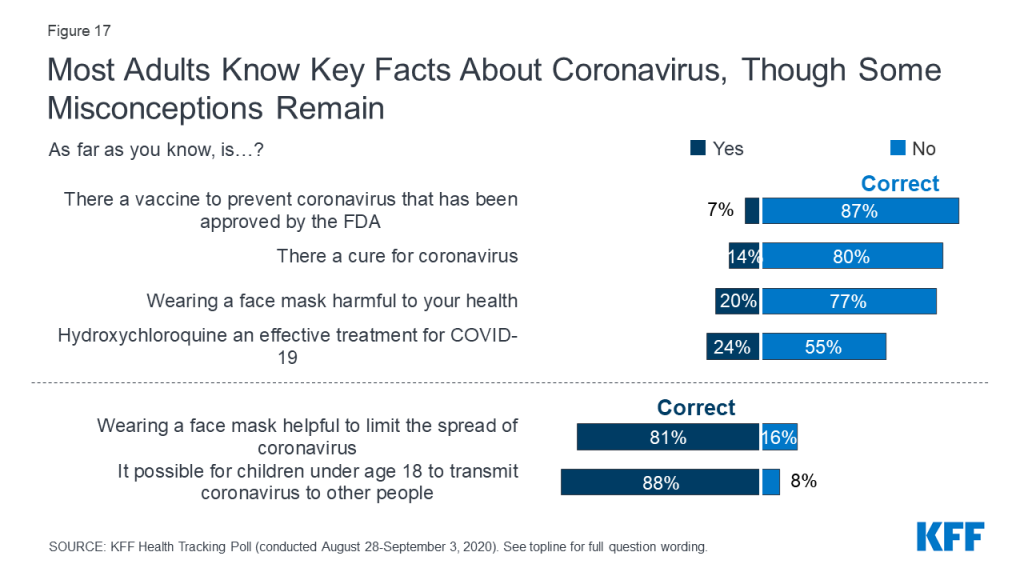

The President has also given conflicting messages and conveyed misinformation about coronavirus and has sometimes been at odds with public health officials (including those in the government) and scientific evidence. For example:

- He has touted the use of the drug, hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19, despite the lack of evidence of its effectiveness, warnings of potential harms, and even after federal COVID-19 treatment guidelines recommended against its use.

- He suggested that applying ultraviolet light to or inside the body, or injecting disinfectant, could combat coronavirus.

- He has attributed rising COVID-19 cases to increased testing, despite the fact that this claim is not backed up by the data.

- He has questioned the use of face masks, and given inconsistent messages about their use, even after CDC guidelines recommended them. It was only in July that he began to wear one in public at times and talk about their importance.

- In pushing schools to re-open in person, he has said that children are “almost immune” and “don’t have a problem,” despite evidence to the contrary.

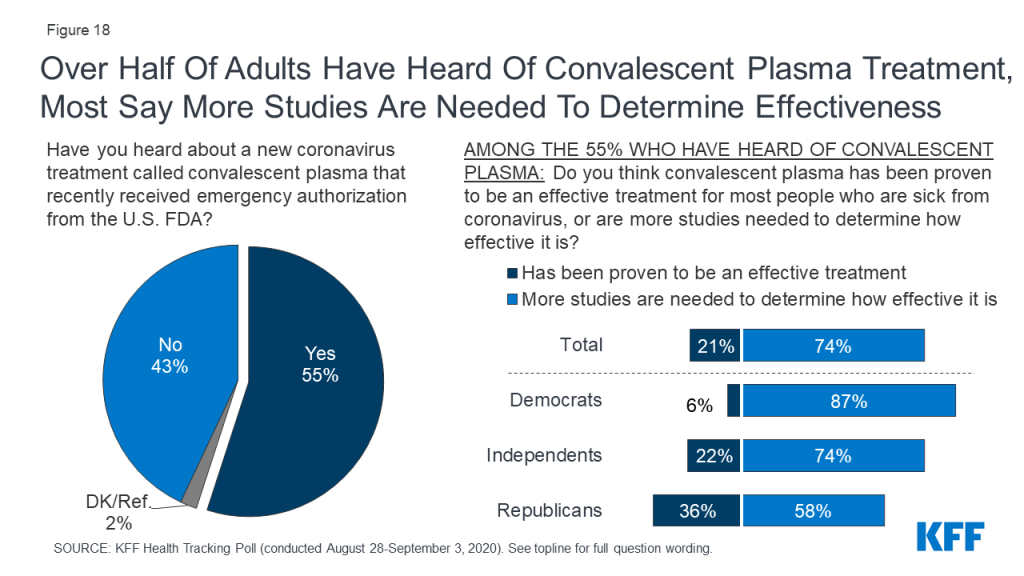

- He called the FDA’s issuance of an emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma, a potential treatment for COVID-19, “historic” and a “breakthrough,” even though the FDA itself said it “may be effective” and the National Institutes of Health COVID-19 treatment guidelines panel concluded that there were insufficient data to recommend either for or against it and at this time, it “should not be considered standard of care for the treatment of patients with COVID-19.”

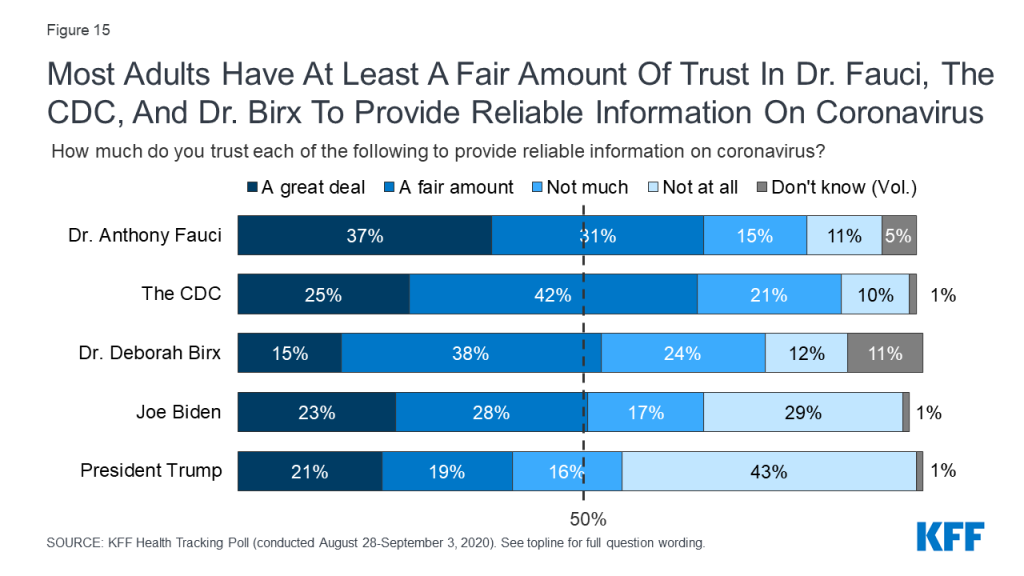

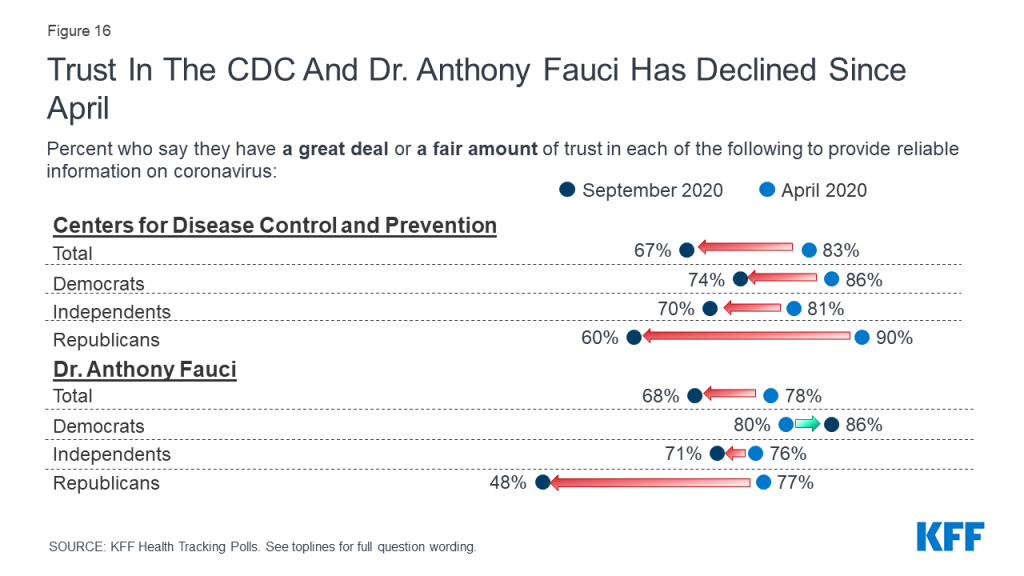

President Trump and White House officials often publicly disagreed with the recommendations being made by federal officials and public health scientists. The CDC, which in previous national public health emergencies was very much in the public eye, did not give press conferences. The President has also publicly criticized Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has been the Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health since 1984, and generally not appeared in public with him recently, unlike earlier in the pandemic.

Even as the administration’s primary strategy was to rely on states, it has taken a number of actions to address the pandemic. The President established a White House COVID-19 Task Force on January 27, even before the WHO had declared COVID-19 to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) (although leadership of the Task Force has shifted and its public-facing and internal activities have diminished). Three federal emergencies have been declared, enabling the authorization of funds and allowing the mobilization of resources and enhanced flexibilities to respond, as follows: HHS declared a public health emergency (PHE) on January 31 (renewed since then) and the President declared national emergencies under the Stafford Act and the National Emergencies Act, on March 13.

The President has also signed four emergency spending bills passed by Congress, which provide trillions to address COVID-19 and offer new flexibilities and relief for individuals, businesses, states, and localities. He has activated the use of the Defense Production Act (DPA) to expand production, prioritize, and allocate supplies in the U.S., if needed, and this authority has been used in select cases. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has provided emergency use authorization for hundreds of tests and other devices and the CDC has issued more than 170 guidance documents on COVID-19. In addition, the U.S. has launched “Operation Warp Speed”, a significant initiative to expedite research, development, and distribution of coronavirus vaccines. Finally, numerous other federal agencies have acted to help ease the burden of COVID-19, such as granting state Medicaid programs additional flexibilities, accelerating Medicare payments to hospitals and other health care providers, instituting new protections for nursing home residents, and issuing a strategy for “Accelerating Progress Towards Reducing COVID-19 Disparities and Achieving Health Equity.”

These measures are taking place against the backdrop of other non-COVID-19 specific Administration actions that could significantly affect the response, such as a continued push before the Supreme Court to overturn the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has provided millions of Americans with insurance coverage and expanded access to health care.

On the global front, two of the emergency spending bills included funding for other countries, and the Administration had already begun sending international assistance to countries in need before the bills were passed. Following a more general foreign policy approach of “America First”, the Administration has chosen not to participate in several high-level international efforts to address COVID-19, has ended funding for the WHO, and has announced its intent to withdraw from WHO membership, actions that mark a significant departure from the role the U.S. has historically played, including its major role in combating the 2014 Ebola outbreak.

As part of his second term agenda, the President recently released the following goals for his proposal to “eradicate COVID-19”:

- “Develop a Vaccine by The End Of 2020.”

- “Return to Normal in 2021.”

- “Make All Critical Medicines and Supplies for Healthcare Workers in The United States.”

- “Refill Stockpiles and Prepare for Future Pandemics.”

Joe Biden

Former VP Biden has outlined a number of proposals for how he would address the coronavirus pandemic as President. VP Biden was also part of the Obama Administration’s response to the 2009 H1N1 outbreak, the 2014 Ebola outbreak, and 2016 Zika outbreak. During his tenure, the Obama Administration played a lead role in creating the “Global Health Security Agenda,” a multilateral initiative that aims to serve as “a catalyst for progress toward the vision of attaining a world safe and secure from global health threats posed by infectious diseases.” In addition, as follow-up to the 2014 Ebola outbreak, the Obama Administration established the Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense at the National Security Council (NSC) to lead the federal government’s pandemic response (the Directorate was disbanded by the Trump Administration in 2018).

VP Biden has put forth the following principles for his proposed response to COVID-19:

- “Restoring trust, credibility, and common purpose”.

- “Mounting an effective national emergency response that saves lives, protects frontline workers, and minimizes the spread of COVID-19”.

- “Eliminating cost barriers for prevention of and care for COVID-19”.

- “Pursuing decisive economic measures to help hard-hit workers, families, and small businesses and to stabilize the American economy”.

- “Rallying the world to confront this crisis while laying the foundation for the future”.

VP Biden’s plan states that “The federal government must act swiftly and aggressively” and that “Public health emergencies require disciplined, trustworthy leadership grounded in science.” His approach calls for the federal government, not the states, to assume primary responsibility for many aspects of the COVID-19 response, including for scaling up testing and contact tracing, providing and managing the distribution of critical supplies, and setting strong national standards. For example, VP Biden has said he would call on all Americans to wear masks and work with governors and mayors to mandate mask wearing. He would appoint a “Supply Commander” to oversee national supply chain of essential equipment, medications, protective gear, directing distribution of critical equipment as cases peak at different times in different states or territories, and make more aggressive use of the DPA to direct companies to produce needed supplies. Additionally, in recognition of the disproportionate toll COVID-19 has taken on racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S., VP Biden would establish a “COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Disparities Task Force”.

VP Biden has also called for adopting measures that go beyond what have been passed by Congress or supported by the Administration to further extend fiscal relief to individuals, schools, and businesses, provide enhanced insurance coverage, support states in providing COVID-19 related services, and eliminate cost-sharing for COVID-19 treatment. For example, VP Biden would reopen enrollment for marketplace plans and cover COBRA at 100% for those who lose their jobs and health insurance due to COVID-19. In addition, VP Biden would further expand paid leave for sick workers and those caring for family members, among others, due to COVID-19, and provide additional pay for frontline/essential workers. On vaccine pricing, he would authorize the federal government to approve the price of any COVID-19 vaccine developed with federal resources, in contrast to the Trump Administration, which has said it does not want to pursue price controls. On schools, a key difference between Biden and Trump is Biden’s emphasis on the need to get the virus under control before reopening in-person education. More broadly, VP Biden proposes to expand and protect the ACA.

On the global front, VP Biden would “re-embrace international engagement,” leadership, and cooperation. His platform states that “Even as we take urgent steps to minimize the spread of COVID-19 at home, we must also help lead the response to this crisis globally. In doing so, we will lay the groundwork for sustained global health security leadership into the future.” He would act to restore the Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense at the NSC and work to help create a Global Health Emergency Board to harmonize crisis response for vulnerable communities around the world. Finally, he would restore funding to and fully resource the WHO and reverse the Trump Administration’s decision to withdraw from WHO membership.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, the following are the primary sources for this side-by-side:

President Trump:

- https://www.donaldjtrump.com/media/timeline-the-trump-administrations-decisive-actions-to-combat-the-coronavirus/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-trumps-historic-coronavirus-response/

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-is-taking-decisive-action-to-protect-vulnerable-citizens-in-americas-nursing-homes/

Vice President Biden:

- https://joebiden.com/covid19-leadership/#issue-0-4

- https://joebiden.com/covid19/:

- https://joebiden.com/reopening/

- https://joebiden.com/fact-sheet-how-joe-biden-would-help-you-get-health-insurance-coverage-during-the-coronavirus-crisis/

- https://medium.com/@JoeBiden/statement-by-vice-president-joe-biden-and-the-biden-for-president-public-health-advisory-committee-6407f37c93da

- https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/12/opinion/joe-biden-coronavirus-reopen-america.html

- https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6982369-Biden-Supply-Chain-Fact-Sheet-07-07-20.html

Table: Side-by-side

Federal Emergency Power

| Trump | Biden |

The Trump Administration has declared three federal emergencies:

|

Travel Restrictions

| Trump | Biden |

Travel restrictions and limitations put in place include the following:

|

Emergency Spending Bills

| Trump | Biden |

Congress passed and the President signed four emergency spending bills:

|

Coordinating a Federal Response

| Trump | Biden |

| Establish a White House COVID-19 Task Force on January 27. | Biden has said that, as President, “the first step I will take will be to get control of the virus that’s ruined so many lives….We will never get our economy back on track, we will never get our kids safely back to school, we will never have our lives back, until we deal with this virus.” He would implement a national strategy on day one of his Presidency. |

Federal Social Distancing and Reopening Guidelines

| Trump | Biden |

The White House:

| Biden:

|

Reopening Schools

| Trump | Biden |

|

|

Scaling up COVID-19 Testing and Contact Tracing

| Trump | Biden |

Under President Trump:

| Biden proposes to:

|

Addressing the Costs of COVID-19 Testing, Prevention, Treatment and an Eventual Vaccine

| Trump | Biden |

Congress has passed and the President has signed emergency relief measures eliminating costs for testing, preventive services, and an eventual vaccine (but in most cases, not for treatment) as follows:

| Biden would work to eliminate cost-barriers (co-payments, deductibles, surprise billing) for all COVID-19 services and commodities, including testing, preventive services, treatment, and an eventual vaccine, for both those who are insured and uninsured, by:

|

Health Insurance Coverage During the Emergency Period

| Trump | Biden |

In response to COVID-19, the Administration has:

| In response to COVID-19 specifically, Biden proposes to:

|

Helping Workers/Workplaces

| Trump | Biden |

Under President Trump:

| Biden would work to:

|

Helping Hospitals/Health Care Facilities & Providers

| Trump | Biden |

Under President Trump:

| Biden proposes to:

|

Building the Strategic National Stockpile & Critical Supplies

| Trump | Biden |

Under President Trump:

| Biden proposes to:

|

Research & Development/ Treatment and Vaccine Distribution

| Trump | Biden |

Under President Trump:

| Biden proposes to:

|

International Cooperation and Global Health Security

| Trump | Biden |

Under President Trump:

| Biden proposes to:

|