Federal law limits the extent to which states can charge premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid because the Medicaid population is low-income. States may not charge premiums to Medicaid enrollees with incomes below 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL). Maximum allowable cost-sharing in Medicaid varies by type of service and income, with total family out-of-pocket costs (premiums and cost-sharing) limited to no more than 5% of family income. A large body of research shows premiums serve as a barrier to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage; even relatively small levels of cost-sharing are associated with reduced care, including necessary services, as well as increased financial burden for families; and state savings from premiums and cost-sharing in Medicaid are limited. This brief reviews and summarizes the most recent literature on the impact of premiums and cost-sharing on low-income populations. We also summarize approved Section 1115 demonstration waivers allowing eight states to charge premiums to enrollees below 150% FPL (AZ, AR, GA, IN, IA, MI, MT, and WI) and analyze available data on the impact of these premiums from five states (AR, IN, IA, MI, and MT). States generally may not use Section 1115 authority to waive other cost-sharing protections such as statutory limits on co-payment amounts.

Our review of recent literature on premiums and cost-sharing is based on studies and reports published between 2017 and 2021. Our analysis of premiums in post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) Section 1115 waivers (approved under the Obama and Trump administrations) is based on available interim and final waiver evaluations as well as annual and quarterly state data reports posted on Medicaid.gov. Key findings include:

- Recent studies bolster earlier research on premiums and cost-sharing for low-income populations, indicating that these policies lead to reduced coverage, worse access to care, and increased financial burden.

- Eight states have CMS approval to implement Section 1115 waivers with premium requirements, with stated goals of these requirements including increasing personal responsibility and ensuring program sustainability.

- While specific premium policies vary across states that have Section 1115 approval for premium requirements, available data and evaluations from five states that have implemented these requirements show that high numbers of enrollees fail to pay premiums, face consequences for nonpayment, and experience confusion over premium policies.

During the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE), states may not disenroll those who fail to pay premiums. Of the six states that had been implementing Section 1115 premiums prior to the PHE, three have continued to charge these premiums while the other three have temporarily waived or suspended these premiums. After the PHE ends, states must determine whether and how to resume premium policies. Looking ahead, changing waiver policy under the Biden Administration could also impact the future of Medicaid premiums under Section 1115 waivers. In addition, as Congress considers options to provide coverage for people in the coverage gap, understanding the implications of premium requirements may help inform those options.

What does the literature tell us about the effects of premiums and cost-sharing on low-income populations?

An earlier literature review found that premiums serve as a barrier to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage for low-income individuals, with those who lose coverage facing increased barriers to accessing care. Research indicated that these effects are largest among those with the lowest incomes. Studies also found that even relatively small levels of cost-sharing are associated with reduced use of care and increased financial burden. Research suggested that state savings from premiums and cost-sharing in Medicaid and CHIP are limited, and that increases in premiums and cost-sharing can increase pressures on safety net providers.

A review of recent studies continues to support earlier research on the impacts of premiums and cost-sharing among low-income populations. We reviewed research from 24 papers published between April 2017 and May 2021 on the effects of premiums and cost-sharing on low-income populations (usually defined as at or below 250% of the federal poverty level (FPL)). Additional research on the impact of premiums from Section 1115 waiver reports are described in a later section of this brief. Literature in this section includes peer-reviewed studies and freestanding reports, government reports, and white papers by research and policy organizations. Key findings include the following:

Premiums lead to decreased coverage for low-income individuals, with negative impacts on health access and outcomes for those who lose coverage. Studies find that premiums reduce insurance coverage and increase disenrollment among low-income individuals, though in some instances these effects were limited to healthier individuals only.1 ,2 ,3 ,4 Those who disenroll, are disenrolled, or otherwise lose coverage due to premiums are at increased likelihood of remaining uninsured and may experience worse health outcomes, decreased health care utilization, worse quality of health care, and increased financial burden.5 ,6 ,7 Other research shows that administrative burdens on eligibility and enrollment processes, such as having to re-apply to regain coverage, result in some eligible people remaining unenrolled.

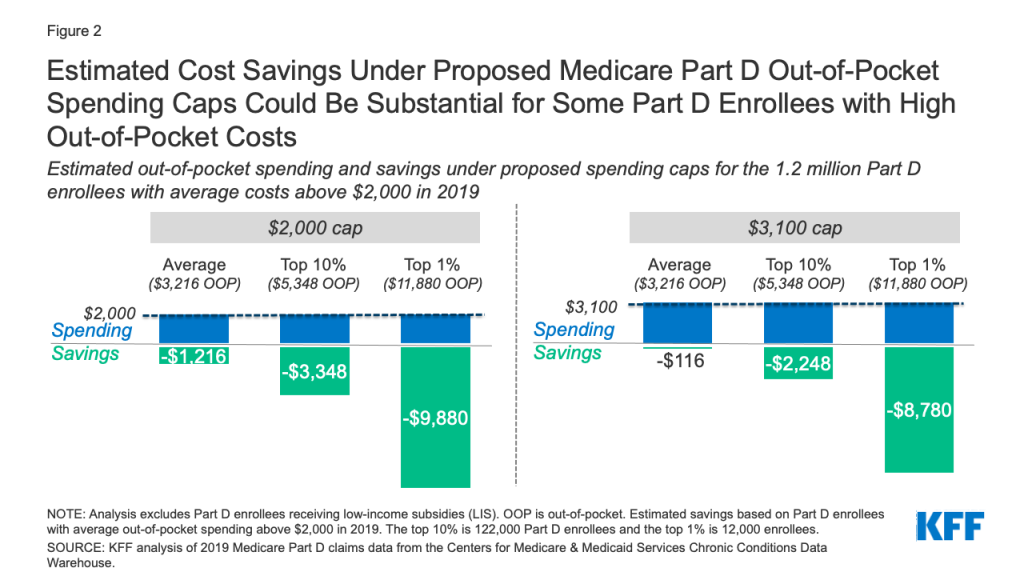

Cost-sharing is associated with reduced use of care, worse health outcomes, and increased financial burden. Studies find that higher out-of-pocket costs are associated with decreased access to and utilization of care, including for individuals with significant health needs.8 ,9 ,10 ,11 ,12 ,13 ,14 ,15 ,16 In particular, studies indicate that higher cost-sharing contributes to decreased prescription refills.17 ,18 ,19 ,20 ,21 ,22 ,23 Several studies find that higher out-of-pocket costs are associated with worse health outcomes including increased mortality and unintended pregnancies.24 ,25 ,26 ,27 ,28 Finally, cost-sharing results in higher costs, decreased affordability, and greater financial burden for low-income adults.29 ,30 ,31 ,32 ,33 ,34 ,35

One more recent study supported earlier findings of limited state savings from premiums and cost-sharing. The study finds that increasing premiums leads to lower-cost enrollees disproportionately dropping out, raising the average cost of the remaining insured population and contributing to increased average medical claims.36

What states have approved Section 1115 waivers with premiums and how do they vary?

Following the ACA, eight states have received CMS approval to implement Section 1115 waivers with premium requirements.37 Prior to the ACA, a number of states sought approval for and implemented coverage expansion waivers (under Section 1115 authority) to optionally extend Medicaid eligibility to adults who did not meet categorical Medicaid eligibility requirements (i.e., to childless adults). Many of these waivers provided these adults more limited benefits and charged them higher premiums and cost-sharing than otherwise allowed in Medicaid. Medicaid expansion under the ACA expanded eligibility to nearly all adults with income at or below 138% FPL, including adults without dependents. While most states that have taken up the ACA option to expand Medicaid have implemented the expansion through State Plan authority, some states have sought and received approval to implement the ACA expansion through Section 1115 waivers. The Obama Administration approved certain premium requirement provisions as part of broader ACA Medicaid expansion Section 1115 waivers. Under the Trump Administration, CMS allowed states to apply these premium requirements to broader populations (i.e., non-expansion/traditional) and to charge higher premium amounts than previously approved. States generally may not use Section 1115 authority to waive other cost-sharing protections such as statutory limits on co-payment amounts.38

Stated goals of Section 1115 premium requirements include increasing personal responsibility and ensuring program sustainability (Appendix Table A). Appendix Table A summarizes goals of these post-ACA 1115 premium requirements across states with approved waivers. Across these goals, states hypothesize benefits of premiums for beneficiaries, including improving health outcomes and health literacy, increasing personal responsibility, and preparing enrollees to transition off Medicaid by aligning the program more closely with commercial coverage. States also hypothesize economic benefits of Section 1115 premiums for themselves, with another common goal being to ensure the fiscal sustainability of the Medicaid program.

Table 1: Approved Section 1115 Waivers with Premium Requirements

>

Key differences in approved Section 1115 premium policies across states include the populations subject to premiums, amounts charged, consequences for nonpayment, and other provisions (Table 1):

Populations. Six states (AR, AZ, IA, IN, MI, and MT) have approval to require expansion adults to pay premiums, though the income groups subject to premiums vary across these states. Under the Trump Administration, CMS approved waivers for three states (GA, IN, and WI) to charge premiums to non-expansion adults, including two states (GA and WI) which have not expanded Medicaid under the ACA. In addition to variation by eligibility group and income level, all states exempt some populations from being charged premiums and/or from facing consequences for non-payment, with common exemptions including medically frail populations and American Indian and Alaskan Native (AI/AN) individuals.

Amounts. Most states adjust premium amounts by beneficiary income, with approved possible charges ranging from approximately $5 to $74 per month. Four states (AR, AZ, MI, and MT) have approved waivers to require monthly premium payments as a percentage of income. Except for Michigan, these states all have approval to charge premiums equal to 2% of household income; Michigan currently charges 2% of income as well but has received CMS approval to raise this amount to 5% of income (which, once implemented, would make it the state with the highest premiums). The other four states (GA, IA, IN, and WI) have approval to charge fixed dollar premiums, three of which vary these amounts by income level (GA, IA, and IN). One of these states, Indiana, had previously charged premiums as a percentage of income but subsequently replaced this requirement with fixed dollar premiums to ease administrative burden.

How premiums are paid. In most states which have implemented premiums, enrollees pay premiums directly to the state, though in two states (AR and IN), enrollees pay premiums to health plans. States and/or health plans generally allow enrollees to pay premiums online (using credit/debit cards or bank account information) or by mail (using checks, cash, and/or money orders). States and/or plans may also allow enrollees to pay in person or by payroll deductions through eligible employers. In states where health plans charge premiums, payment options may vary by plan. Three states (AZ, IN, and MT) allow third party payers (such as employers or nonprofits) to make premium payments on behalf of enrollees.

Consequences for nonpayment. Six of eight states (AZ, GA, IA, IN, MT, and WI) have approval to impose some form of coverage loss for missed premiums (following a grace period) for at least some beneficiaries. In three of these states (AZ, GA, and IA), individuals who fail to pay premiums will lose coverage but may reapply at any time. In the other three states (IN, MT, and WI), individuals who fail to pay are disenrolled from coverage and locked out for a period of six months (IN and WI) or an indefinite period until all missed premiums are paid or until the state sends the individual a notice of collectible debt (MT). In Indiana, although only individuals above 100% FPL face coverage loss for nonpayment, enrollees below 100% FPL who fail to pay premiums receive a more limited benefit package (without coverage of vision, dental, and other services) and owe point-of-service co-payments. In most states, all individuals (including those not subject to coverage loss consequences) may face debt collection of unpaid premiums. Once unpaid premiums are considered collectible debt, states and/or health plans typically recover this debt from state tax refunds, but face some restrictions (e.g., may not place a lien on the individual’s home and may not sell the debt to a third party).

Additional provisions. In addition to monthly premiums, two states (GA and IN) have approval to charge a tobacco premium surcharge which increases the monthly amount owed for enrollees who use tobacco (by $3-$5 in GA and $1.50-$30 in IN, with both states varying the surcharge amount by income level).39 Six states (AZ, GA, IA, IN, MI, and WI) with approved premiums also have approved healthy behavior incentives that may reduce premium amounts if completed. Four states (AZ, GA, IN, and MI) have approval to deposit paid premiums into a member savings account that may be used to deduct copays. Arkansas has approval for a Qualified Health Plan (QHP) premium assistance program, through which expansion adults are required to enroll in and pay premiums for Marketplace QHP coverage, with premium assistance from the state to reduce these premiums to no more than 2% of income.

What does the data show on the impact of premiums under Section 1115 waivers?

In this section, we analyze data from five states that have implemented Section 1115 premium requirements (AR, IN, IA, MI, and MT) on rates of premium nonpayment and consequences, reasons for nonpayment including confusion and affordability, and administrative burden. Our analysis is based on interim and final waiver evaluations as well as annual and quarterly state data reports posted on Medicaid.gov. Although we highlight key themes across states, comparison between states is limited by state-by-state variation in premium policies and available data metrics.

Available data from quarterly and annual state waiver reports suggests that high numbers of enrollees fail to pay premiums. Common reasons for nonpayment include confusion and affordability (see details below). For example, in Montana (a state with particularly robust data), for each month in 2019 an average of 57% of enrollees failed to pay that month’s premium, while 74% had an overdue premium for a prior month (Figure 1); these percentages were similar in 2017 and 2018.40 Lower-income enrollees in Montana were more likely to fail to pay: an average of 61% of those between 50% and 100% FPL failed to pay that month’s premium versus 52% of those above 100% FPL (data not shown).

Available data from other states also suggests high rates of nonpayment: in Arkansas, from January 2015 through April 2016, just 14% of enrollees made at least one eligible premium payment. In Michigan, between October 2014 and January 2021, fewer than half (47%) of those who owed premiums made at least one payment. During this time period, the state only collected 26%, or approximately $23.8 million, of the $92.3 million in premium payments owed. In Indiana, from February 2015 through November 2016, 55% of all individuals subject to premiums had at least one missed premium payment and faced consequences.

Data indicates that many enrollees have faced an array of consequences for failure to pay premiums, including loss of coverage.

- Loss of coverage or benefits. Data shows that individuals with incomes above 100% FPL subject lost coverage in Montana, Indiana, and Iowa due to failure to pay premiums. In Montana, a total of 1,800 individuals lost coverage due to nonpayment of premiums in 2019 (nearly one in four of those subject to coverage loss).41 In Iowa, a total of 2,200 individuals were disenrolled due to failure to pay premiums in 2019 (16% of those subject to coverage loss).42 In Indiana, from February 2015 through November 2016, of those eligible to pay premiums with incomes above 100% FPL, just over half (51%) were never enrolled in coverage (46,200 individuals) or lost coverage (13,600 individuals) due to failure to pay. Nearly half (47%) of those eligible to pay premiums with incomes below 100% FPL were moved from the comprehensive to the more limited benefit package due to failure to pay (286,900 individuals in total).

- Debt collection. In addition, data show that individuals in Iowa, Montana, and Michigan were subject to debt collection due to premium non-payment. For example, in Iowa, a total of 5,300 enrollees faced debt collection due to failure to pay premiums in 2019 (more than one in 10 of those subject to premiums).43 In Montana, for each month in 2019 about 30% of all non-exempt enrollees were subject to debt collection as a consequence for premium nonpayment (Figure 1). As of August 2017, about 186,000 Michigan beneficiaries owed past due premiums or co-payments, and over 40% of these were in “consistent failure to pay” status, subjecting them to garnishment.44

Available data from evaluation reports indicates that many enrollees experience confusion over premium policies. Unlike employer-sponsored insurance plans which typically require workers to contribute some share of premium costs by automatically deducting these from employee paychecks, premium policies implemented as part of Section 1115 Medicaid waivers generally require enrollees to actively remit payment each month, typically online or by mail. For example, reports from Iowa and Indiana show that the most common reasons for nonpayment of premiums included not knowing payment was required and forgetting to pay or confusion about payment process (in addition to affordability, discussed below). State reports also indicate that policies related to premiums such as member savings accounts and healthy behavior incentives similarly may result in confusion for enrollees. Other examples include the following:

- An Iowa survey of individuals disenrolled for failure to pay premiums found that fewer than 40% were aware that they owed a premium while receiving coverage. Just 34% of those disenrolled for premium nonpayment knew that they were being disenrolled before it happened (despite the state’s 90-day grace period for premium nonpayment).

- In Montana, the majority of enrollees (current and those disenrolled for premium nonpayment) knew that monthly premiums were dependent on income; however, focus groups reported multi-hour wait times when trying to obtain help understanding premium policies. Fewer Montanans were aware of the consequences for nonpayment and options for retaining or reenrolling in coverage following nonpayment.45

- Indiana reports that while most members understood payment obligations generally (i.e., the fact that they owed premiums), fewer understood the consequences for nonpayment. Although only enrollees above 100% FPL are subject to coverage loss and lock-out in Indiana, evidence from focus groups suggests that individuals at all income levels thought that this consequence for premium nonpayment applied to them. Officials in Indiana indicated that member understanding of premium obligations may have improved following the transition from a 2% of income premium structure to a fixed dollar amount structure.

- An analysis from Michigan reveals that although the state currently does not impose coverage loss as a consequence for nonpayment of premiums, enrollees subject to premiums were more likely to disenroll from the program.

Many enrollees reported that their premiums were not affordable. In Iowa and Indiana, the most common reason for failure to pay premiums was inability to afford payment. In Montana, 15% of “current enrollees” (subject to premiums) and 80% of those disenrolled for failure to pay premiums reported that premiums were more than they could afford. In Indiana, 15% of current enrollees and 41% of those disenrolled for failure to pay premiums reported that they always or usually worried about having enough money to pay premiums. Among individuals in Michigan who disenrolled from Medicaid, those who remained uninsured were less likely to agree that Medicaid premiums were fair and affordable. Of individuals disenrolled for failure to pay premiums in Iowa, 44% lacked coverage and 31% stated that their health had declined following disenrollment. In Montana, the large majority of those disenrolled for failure to pay premiums were found to be eligible through an alternative Medicaid pathway, suggesting that they had lower incomes and qualified for “standard Medicaid” coverage without premium requirements.

Limited available data suggests that premiums may cause high administrative burden and in some cases have resulted in the discontinuation of program elements. States are not required to report administrative data—including state costs to build and operate the infrastructure required to implement premium requirements—associated with Section 1115 waiver implementation.

- In Arkansas, in 2016 administrative costs for the state’s Section 1115 waiver were nearly 30% higher as compared to standard Medicaid (though the state does not identify specifically the reasons for these higher costs).

- In 2018, Indiana replaced its 2% of income premium requirement with a fixed dollar premium requirement that varies across five income tiers, explaining that this simpler structure would ease administrative burden from both a systems and member communication perspective.

- Two years after implementing its premium requirements, Montana discontinued two provisions related to premiums due to administrative and budgetary concerns. The state initially provided coverage to non-exempt enrollees through public-private third-party administrator (TPA) plans but eliminated this program element due to state budgetary concerns, citing the belief that shifting to state collection of premiums instead of TPA would yield savings in administrative costs. At the same time, Montana also discontinued a provision that provided all enrollees subject to premiums with a credit toward co-payments of up to 2% of income, citing that this credit was too difficult to track and administer.

Without administrative data from most states, it is unclear whether costs to implement premium requirements are typically offset by premium collections, given high rates of nonpayment: for example, while Michigan charged over $92.3 million in premiums from October 2014 to January 2021, enrollees paid less than $23.8 million in premiums over the same time period.

Looking Ahead

Recent literature as well as data from Section 1115 waiver reports and evaluations bolster earlier research finding that premiums may serve as a barrier to obtaining and maintaining Medicaid coverage, are confusing and unaffordable to enrollees, and that states’ premium collections may not offset administrative costs. Looking ahead, both the continued COVID-19 emergency and actions at the federal level could impact premiums in Medicaid, though the Biden Administration’s stance on premiums requirements approved through Section 1115 waivers is not yet clear. Three states (AR, MI, and MT) are still charging premiums during the PHE (though maintenance of eligibility requirements prohibit them from disenrolling those who fail to pay and also prohibit states from increasing premium amounts), while the remaining states have temporarily waived or suspended premiums. When the PHE ends, states must determine whether and how to resume policies including charging premiums, increasing premiums, and/or disenrolling individuals who fail to pay.

At the federal level, Section 1115 waiver policy generally reflects changing priorities from one presidential administration to another. Section 1115 waiver policy could shift under the Biden Administration: in a January 28, 2021 executive order, President Biden directed relevant agencies to review waivers and waiver policies that may reduce coverage under or otherwise undermine Medicaid. CMS subsequently began the process to withdraw waivers with work requirement provisions and indicated that other previously-approved authorities in these waivers—including, in some cases, premium requirements—remained under review. CMS generally reserves the right to withdraw approved waiver authorities at any time, and can also decline to renew or to renegotiate waivers as demonstrations expire. This large body of research and state experience with premium waivers could contribute to decisions about continuing or granting additional waivers to study the effects of such policies. In addition, as Congress considers options to provide coverage for people in the coverage gap, understanding the implications of premium requirements may help inform those options.

The authors thank former KFF Policy Analyst Olivia Pham for her assistance reviewing studies on the effects of premiums and cost-sharing.