KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: The Impact Of The Coronavirus Pandemic On The Wellbeing Of Parents And Children

Findings

Key Findings

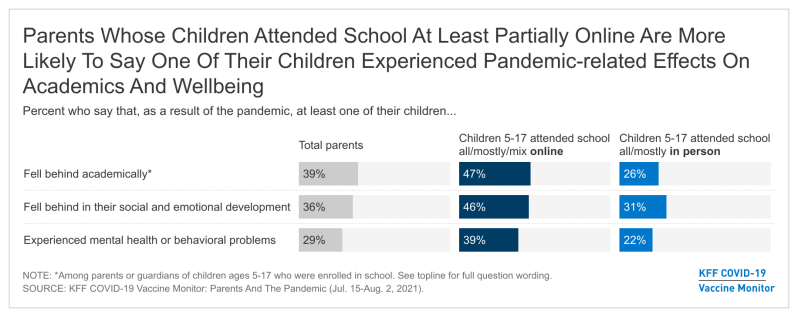

- As students head back to school amid uncertainty caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the latest report from the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds parents reporting notable adverse impacts of the pandemic on children’s academic and social development. About four in ten parents of children ages 5 and over say at least one of their children fell behind academically (39%), rising to half of Hispanic parents (50%) and those with lower household incomes (51%). More than a third (36%) of parents say their child fell behind in their social and emotional development and about three in ten (29%) say their child experienced mental health or behavioral problems due to the pandemic. Notably, parents whose children attended school all or mostly online, or who had a mix of online and in-person schooling were more likely than parents whose child attended school all or mostly in-person to say they had a child who had these adverse effects even after controlling for other demographic factors and type of school.

- When asked about more specific problems that may indicate mental health concerns among children, about four in ten parents (42%) report that at their children experienced at least one new mental health symptoms in the past 12 months that they had not been experiencing them before the pandemic including difficulty concentrating on schoolwork (27%), problems with nervousness or being easily scared or worried (19%,) trouble sleeping (18%), poor appetite or overeating (15%), and frequent headaches or stomachaches (11%). Mothers – who tend to take on greater responsibilities for childcare and are often the primary health care decision makers in a family– are more likely than fathers to say one of their children experienced most of the symptoms since the pandemic began.

- The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that nearly four in ten parents say they or another adult in their household left a job or changed work schedules to care for their children in the past year. Notably, more than half of Black parents (53%) and parents with lower household incomes (51%) say they or another adult in their family left a job or changed schedules in order to care for their children. One in five parents overall say the person in their household who left a job or changed their work schedule is still not working or continues to work reduced hours, rising to one-third of Black parents and nearly four in ten lower-income parents.

- Household employment disruptions may also be related to children’s wellbeing. Parents in a household with an employment disruption are more likely than those who didn’t experience a disruption to say their fell behind academically (51% vs. 32%), fell behind in their social or emotional development (49% vs. 28%), or experienced mental health or behavioral problems (41% vs. 21%). Parents in a household with an employment disruption are also more likely than those who did not experience a disruption to say their child has developed a new mental health symptom since the pandemic began (56% vs. 33%).

- Along with negative impact on children’s mental health, the pandemic appears to have taken a mental health toll on parents. A majority (54%) of parents say the pandemic has had a negative impact on their mental health, compared to 39% of adults overall who say the same. Mothers, Black and Hispanic parents, those with lower incomes, and parents whose household experienced a work disruption due to increased childcare needs have been particularly affected with at least six in ten in each of these groups saying it the pandemic had a negative impact on their mental health.

Effects of the pandemic on children’s academic and emotional development

As students head back to school amid uncertainty caused by the coronavirus pandemic, this new report from the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor examines parents’ assessment of the toll the pandemic has taken on their children and on their own mental health and financial wellbeing over the past 18 months. When asked about specific ways the pandemic may have affected their children, about four in ten parents of children ages 5 and over say at least one of their children fell behind academically (39%), while more than a third (36%) of parents of children of any age say their child fell behind in their social and emotional development and about three in ten (29%) say their child experienced mental health or behavioral problems due to the pandemic.

Notably, half of Hispanic parents say one of their children fell behind academically as a result of the pandemic compared to about a third of White parents (35%) who say the same. Across income groups, half (51%) of parents with a household income under $40,000 say their child fell behind academically compared to about a third (32%) of those with incomes of $90,000 or more.

The coronavirus pandemic caused a tremendous amount of disruption to the 2020-2021 school year. Across the country, millions of students and teachers had to transition to online learning. Previous KFF research at the beginning on the 2020-2021 school year found that about two-thirds of parents were worried about their child falling behind academically or in their social and emotional development if they did not return to in-person school. Indeed, most students were not able to attend in-person school fulltime during this past school year. KFF’s most recent COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that a majority of parents say their child attended school at least partially online during the previous school year (72% of parents of 12-17 year-olds and 62% of parents of 5-11 year-olds). Notably, we find that parents of children whose school was at least partially online are more likely than those whose kids attended school mostly or completely in-person to report that one of their children have experienced a negative impact to their wellbeing1 . These differences may be at least partially due to differences in other demographic characteristics of parents whose child’s schools offered in-person schooling compared to those who did not. However, using a statistical technique called multivariate regression, we find that even after controlling for parent’s race and ethnicity, gender, income, region, age, educational attainment, and party identification and whether they had a child attending private or public school, parents with a child who attended school at least partially online are more likely than those whose children attended school all or mostly in person to report their child experienced a negative impact to their wellbeing due to the pandemic.

Parents whose children attended school all or mostly online, or who had a mix of online and in-person schooling were more likely than parents whose child attended school all or mostly in-person to say they had a child who fell behind academically (47% vs. 26%), fell behind in their social or emotional development (46% vs. 31%), or experienced mental health or behavioral problems (39% vs. 22%).

When asked about more specific problems that may indicate mental health concerns among children, about one in four parents (27%) say their children had difficulty concentrating on schoolwork or completing assignments and that this was a new problem they were experiencing since the pandemic began. About one in five say a child experienced new problems with nervousness or being easily scared or worried (19%) or trouble falling or staying asleep or sleeping too much (18%). In addition, 15% of parents say their children exhibited poor appetite or overeating (15%) and about one in ten say they experienced frequent headaches or stomachaches (11%). Overall, four in ten parents (42%) report that their children experienced at least one of these symptoms in the past 12 months and had not previously been experiencing them before the pandemic.

With the exception of difficulty concentrating on schoolwork, mothers – who tend to take on greater responsibilities for childcare and are often the primary health care decision makers in a family– are more likely than fathers to say one of their children experienced each of the symptoms since the pandemic began. Overall, about half (47%) of mothers report that their child experienced a new problem compared to about to four in ten fathers (37%).

Notably, half of Hispanic parents (52%) and lower-income parents (49%) say one of their children exhibited one of these mental health symptoms in the past 12 months which were not present before the pandemic. In addition, parents of children who attended school at least partially online are more than twice as likely as parents whose children attended school all or mostly in person to say their child experienced new problems concentrating on schoolwork or completing assignments in the past 12 months (41% vs. 17%).

Childcare Needs And Employment Disruptions

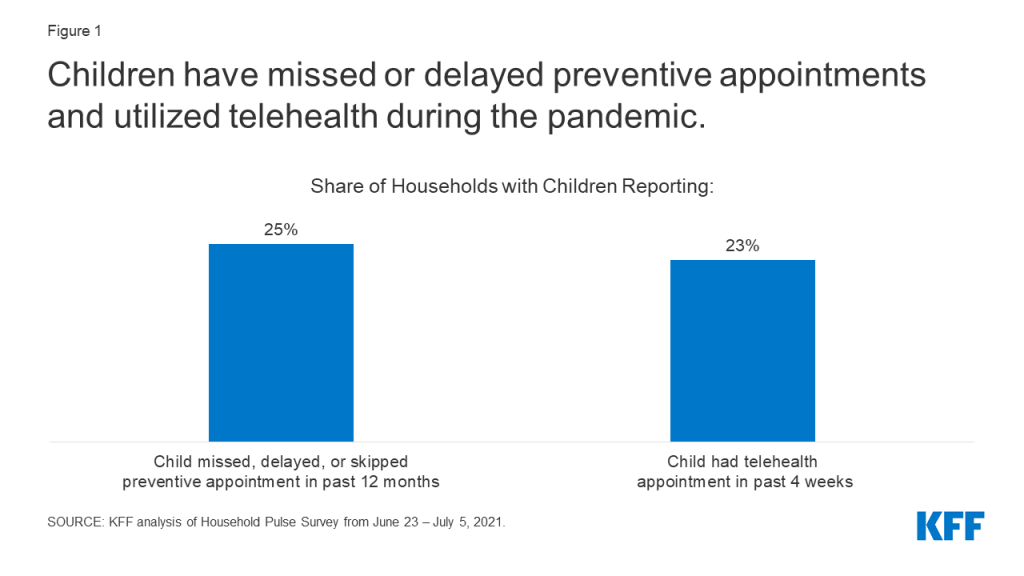

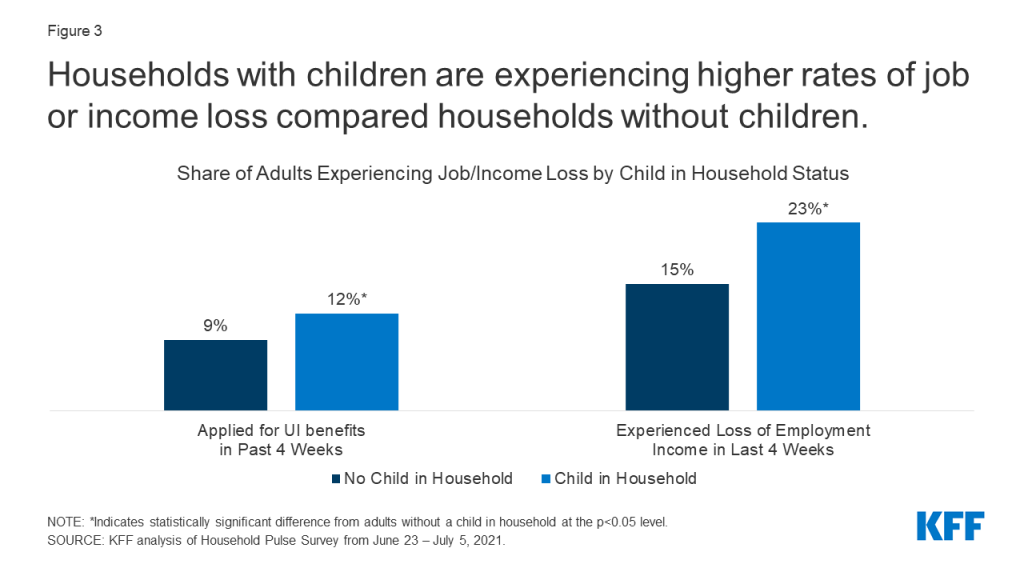

In this past year, the pandemic not only affected children, but has also had an impact on working parents and families across the country. A recent KFF analysis of the Census Household Pulse Survey shows that households with children were more likely to have experienced employment loss. The most recent KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that nearly four in ten parents say they or another adult in their household left a job or changed work schedules to care for their children in the past year. As one might expect, parents of younger children are more likely than those of children ages 12 and older to say their household had an employment disruption due to childcare needs in the past year. In addition, Black parents (53%) and Hispanic parents (44%), those with a household incomes under $40,000 (51%), and parents under age 40 (44%) are more likely than their counterparts to say they or another adult in their family left a job or changed schedules in order to care for their children.

Notably, one in five parents of kids ages 5 and over say at least one of their children had to take on new duties helping to care for siblings or other family members as a result of the pandemic, including 28% of Black parents and 26% of Hispanic parents compared to 15% of White parents.

When asked more specifically how their work arrangements changed to accommodate for increased childcare needs during the pandemic, 16% of parents say they or another adult in their household changed their work schedule and a further 10% say they cut back on hours. About one in ten parents (11%) say they or another adult in their household stopped working temporarily in order to care for their children, rising to one in five among Black parents (20%) and parents with a household income under $40,000 (21%). A further 9% of parents say in the past year they or another adult in their household stopped working permanently in order to care for their children, rising to 17% among Black parents and those with lower household incomes.

Many parents who stopped working or adjusted their work schedules to take care of children during the pandemic have still not returned to work or to their previous schedules. Overall, about half (54%) of parents who report a work disruption due to childcare needs (21% of parents overall) say the person in their household who left a job or changed their work schedule is still not working or continues to work reduced hours. Overall, one-third of Black parents and one in four Hispanic parents say their household has not resumed their previous employment hours after having a childcare-related employment change during the pandemic. Low-income parents are particularly hard-hit, with roughly four in ten parents (39%) with a household income under $40,000 saying their household has not resumed their previous employment hours.

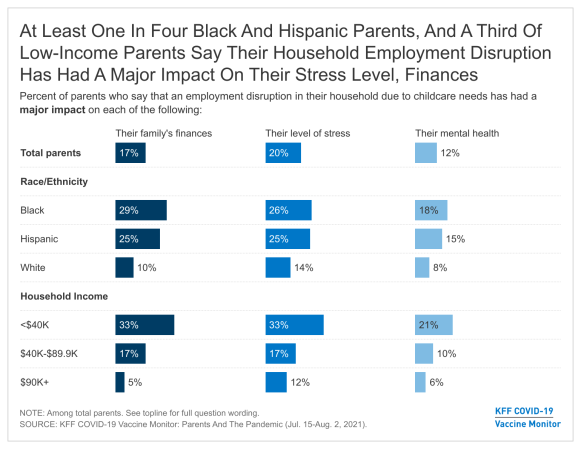

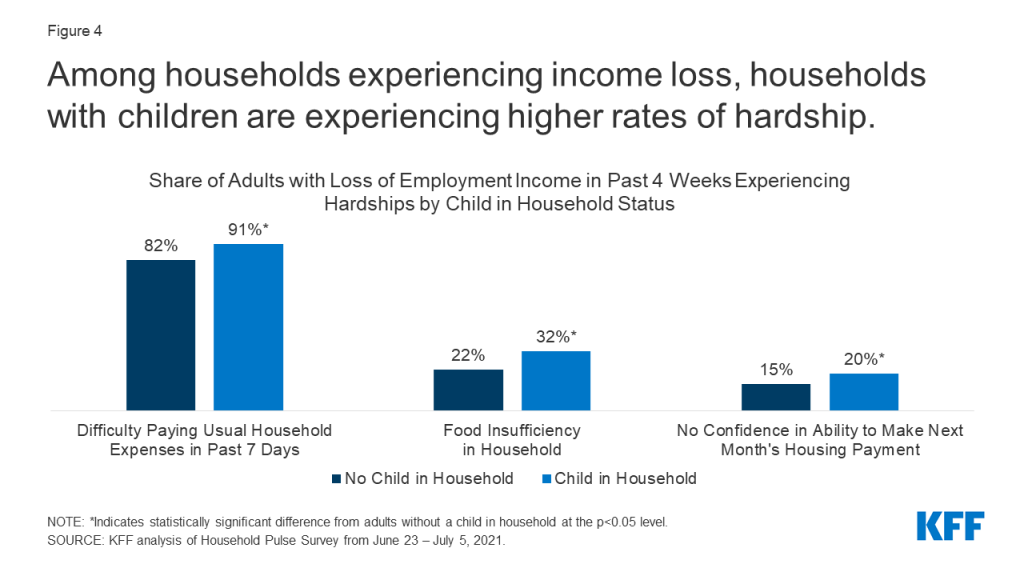

These employment disruptions have added an additional burden to what has already been a difficult year for many parents across the country. Large majorities say their household employment disruption due to childcare needs has had an impact on their stress level (50% say it has had a major impact, 36% a minor impact), their family finances (44% major, 35% minor), and their own mental health (31% major, 39% minor).

Again, Black and Hispanic parents are particularly impacted with about one in four saying their household experienced an employment disruption and that it has had a major impact on their family’s finances and on their stress level. Among lower-income parents, one-third say report experiencing a household employment disruption that has had a major impact on their stress level (33%), and on their family finances (33%) and one in five (21%) report such a disruption has had a major impact on their mental health.

The Impact Of Employment Disruption On Children

When parents experience disruptions in their employment due to increased childcare needs, this may also have an impact on the wellbeing of their children. When assessing the impact of the pandemic on their children, parents in a household that experienced an employment disruption are more likely than those whose household did not experience a disruption to say their child fell behind academically (51% vs. 32%), fell behind in their social or emotional development (49% vs. 28%), experienced mental health or behavioral problems (41% vs. 21%), or had to take on new care duties for siblings or other family members (33% vs. 11%). Overall, about seven in ten parents in households that experienced an employment disruption say one of their children has experienced at least one of these things compared to 44% of those who did not experience a disruption.

Similarly, parents who experienced a household employment disruption are also more likely than those who did not experience a disruption to say their child has developed a new mental health symptom since the pandemic began (56% vs. 33%). Nearly four in ten parents in households that experienced an employment disruption say their child has had difficulty concentrating on schoolwork (37%), about three in ten say their children have exhibited nervousness or being easily scared or worried (29%), and about one in four say they had sleeping disturbances (26%) or issues with eating (26%). One in six say their child experienced frequent headaches or stomachaches (17%).

Mental Health Of Children And Their Parents

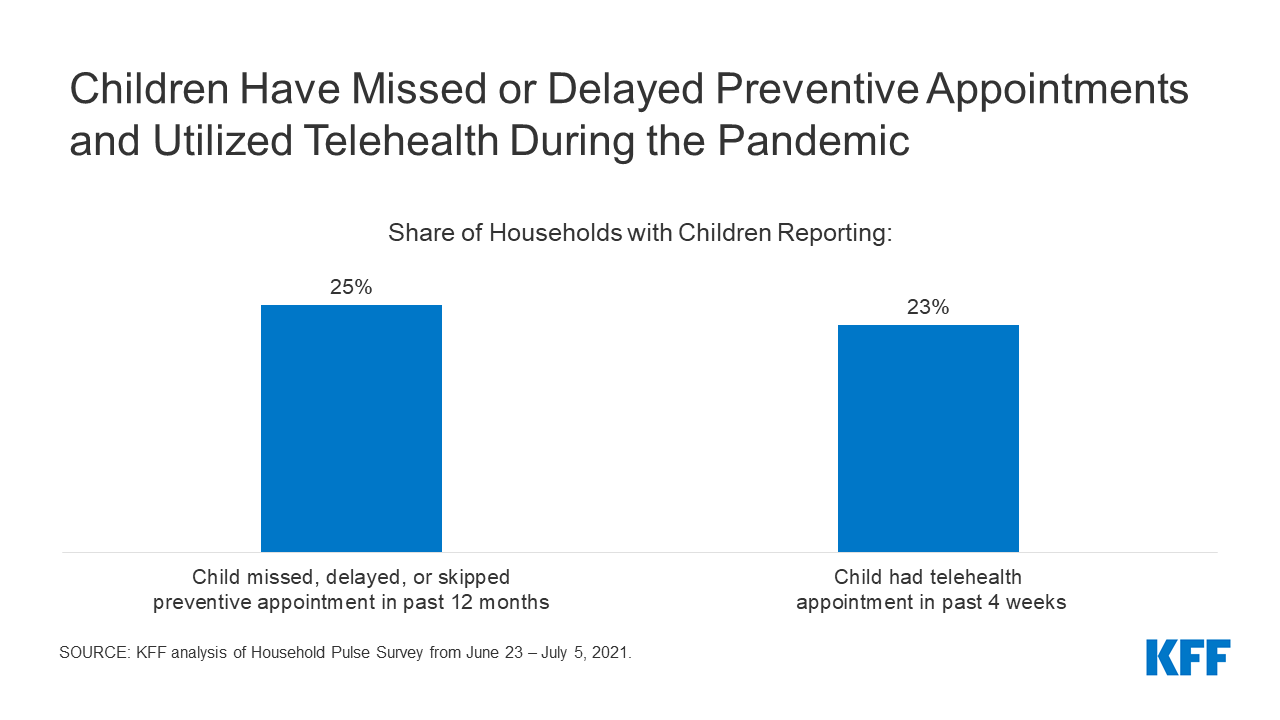

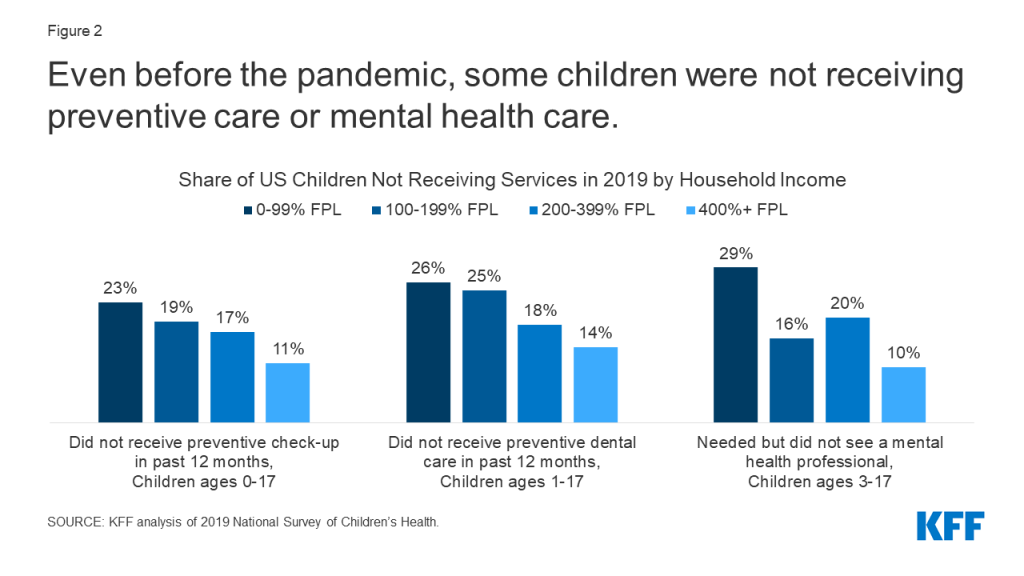

Previous KFF research has shown the even before the pandemic, many children in the U.S. were experiencing mental health problems and there was some evidence last year that the pandemic may have been exacerbating the issue. While three in ten parents report that their children experienced mental health or behavioral problems as a result of the pandemic and an even larger share say their children have experienced new symptoms in the past 12 months that may be associated with mental health concerns, a much smaller share (17%) report that their children received mental health services in the past 12 months. One in nine parents overall (11%) say there was a time in the past 12 months when they thought their child may have needed mental health services or medication but didn’t get them.

Access to mental health services appears to be an issue for those parents who say they thought their child might need mental health care but they were unable to get it. The main reasons parents cite for why their child was unable to get needed mental services include that they could not find a provider (32%), that they were too busy or could not get the time off work (16%), and that they could not afford the cost (15%).

In addition to the effects on children’s mental health, parents themselves are disproportionately likely to say the pandemic has had a negative impact on their own mental health. About four in ten adults overall (39%) report that stress and worry related to coronavirus has had a negative impact on their mental health, a share that rises to 54% among parents (compared to 37% of adults without children at home). The stress and worry over the pandemic has especially affected mothers, Black and Hispanic parents, those with household incomes under $40,000, and parents whose household experienced a work disruption due to increased childcare needs, with at least six in ten in each of these groups saying it has had a negative impact on their mental health.

Mental Health Impacts Over The Course Of The Pandemic

Previous KFF research has found that the share of adults reporting symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder rose to about four in ten during the pandemic, up from about one in ten who reported these symptoms in 2019. While still large share of adults say the stress and worry due to the pandemic has had a negative impact on their mental health, it has decreased slightly from March 2021 (47%) to 39% in the July KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, and is down considerably from 53% a year ago. While the share of adults in the U.S. who are reporting negative mental health impacts from the coronavirus is down slightly, the survey was fielded largely before the news of the increased threat of the Delta variant.

A majority of parents and more than four in ten Hispanic adults, women, those with a chronic health condition, and health care workers say stress and worry related to coronavirus has had a negative impact on their mental health. Smaller shares of non-parents, adults ages 65 and older, men, and those with higher incomes say they have experienced mental health impact from the coronavirus. Previous studies have shown that men, older adults, and Black adults may be less likely to report mental health difficulty and more likely to face challenges accessing mental health care.

Methodology

This KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor – Parents and the Pandemic was designed and analyzed by public opinion researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). The survey was conducted July 15-August 2, 2021 via telephone and online among a nationally representative sample of 1,259 adults who are the parent or guardian of a child under the age of 18 living in their household. The sample includes 351 parents reached through the July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor and 908 who were reached online through a probability-based online panel (SSRS Opinion Panel). The Vaccine Monitor respondents were reached through a random digit dial telephone sample of adults ages 18 and older (including interviews from 101 Hispanic parents and 64 non-Hispanic Black parents), living in the United States. Phone numbers used for the telephone component were randomly generated from cell phone and landline sampling frames, with an overlapping frame design, and disproportionate stratification aimed at reaching Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black respondents as well as those living in areas with high rates of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. The sample also included 43 parents by calling back respondents that had previously competed an interview on a KFF poll (n=11) or SSRS omnibus poll (n=32). The comparison sample of non-parents was also drawn from the July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. See the July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor for further details on the telephone component.

For the online component, invitations were sent to panel members who previously identified as the parent of a child ages 5 to 17. As with the telephone component, Hispanic and Black respondents were oversampled. The SSRS Opinion Panel is a nationally representative probability-based web panel. SSRS Probability Panel members are recruited randomly in one of two ways: (a) Through invitations mailed to respondents randomly sampled from an Address-Based Sample (ABS). ABS respondents are randomly sampled by MSG through the U.S. Postal Service’s Computerized Delivery Sequence (CDS). (b) from a dual-frame random digit dial (RDD) sample, through the SSRS Omnibus survey platform. Sample for the SSRS Omnibus is obtained through Marketing System Groups (MSG).

The combined telephone and online parent samples were weighted to match the sample’s demographics to the national parent population using data from the Census Bureau’s 2019 U.S. American Community Survey (ACS). Weighting parameters included sex, age, education, marital status, child age, and region, within racial/ethnic groups. The weights take into account differences in the probability of selection for each sample type (phone and web). This includes adjustment for the sample design and geographic stratification of the telephone sample, within household probability of selection, and the design of the panel-recruitment procedure.

The margin of sampling error including the design effect for the full sample of parents is plus or minus 4 percentage points. Numbers of respondents and margins of sampling error for key subgroups are shown in the table below. For results based on other subgroups, the margin of sampling error may be higher. Sample sizes and margins of sampling error for other subgroups are available by request. Sampling error is only one of many potential sources of error and there may be other unmeasured error in this or any other public opinion poll. Kaiser Family Foundation public opinion and survey research is a charter member of the Transparency Initiative of the American Association for Public Opinion Research.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF (an advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation), the Ford Foundation, and the Molina Family Foundation. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

| Group | N (unweighted) | M.O.S.E. |

| Total parents/guardians of children under 18 in household | 1,259 | ± 4 percentage points |

| Parent Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 399 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 372 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Hispanic | 429 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Child Age Groups | ||

| Parents of children under age 5 | 523 | ± 7 percentage points |

| Parents of children ages 5-11 | 674 | ± 6 percentage points |

| Parents of children ages 12-17 | 728 | ± 5 percentage points |

| Comparison sample of non-parents (adults who are not parents or guardians of children under 18) from July 2021 KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor | 1,166 | ± 4 percentage points |

Endnotes

- Parents who said they had at least one child who attended school all or mostly online, or a mix of online and in-person were coded as All/Mostly/Mix Online. ↩︎