Browse by Issue:

- Addressing the short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on PEPFAR and the HIV response.

- PEPFAR funding and bipartisan support.

- PEPFAR’s geographic footprint, service portfolio, and population focus.

- The role of community and civil society in PEPFAR and the HIV response.

- PEPFAR, epidemic control, and the long-term sustainability of the HIV response.

- PEPFAR’s role in global health security and broader health systems strengthening.

- PEPFAR and the Global Fund.

- PEPFAR’s structure and location within the U.S. government’s global health architecture.

Introduction

The Biden administration has inherited the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) at a critical time for the program and the fight against HIV, as it faces important strategic decisions and new challenges, not the least of which being the continuing impact of COVID-19. PEPFAR, the U.S. government’s signature global health effort, is broadly regarded as one of the most successful programs in global health history. Conceived of as an emergency initiative and launched by President George W. Bush in 2003, when HIV was ravaging much of sub-Saharan Africa, PEPFAR, along with the creation of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), ushered in a significant increase in funding and attention to the global HIV response, with bilateral HIV funding more than tripling in the program’s initial five-year period, rising from $1.6 billion in 2004 to $5 billion in 2008 (see Figure 1).

Due in no small part to sustained U.S. support, many of the countries that were being devastated by HIV at the turn of the millennium have recorded major progress in preventing new HIV infections and deaths, including a number that appear to be on the cusp of achieving PEPFAR’s epidemic control target.3 PEPFAR reports that it has saved 20 million lives, prevented millions of new HIV infections, and contributed to progress towards elimination of mother-to-child HIV transmission, and a number of external analyses and evaluations have documented its impact (see Box 1 for additional PEPFAR results).4 ,5 ,6

| Box 1: PEPFAR Reported Results |

- Countries Reached: 50+

- People Receiving Antiretroviral Treatment (as of September 2020): 18.2 million

- Babies Born Free of HIV (as of September 2020): 2.8 million

- New Health Care Workers Trained (as of September 2020): 290,000

- People Receiving HIV Testing Services (in FY2020): 50 million

|

| SOURCE: U.S. Department of State, PEPFAR Latest Global Results; June 2021. |

However, PEPFAR is at a turning point. Much has changed since the program was created, including important shifts in the global HIV burden, a substantial expansion of the array of validated HIV prevention and treatment tools, and notable changes in the global health and development landscape. The lens through which the HIV response is viewed has also shifted, with a growing focus on addressing inequalities and promoting equity, principles endorsed, for example, in a new UNAIDS global AIDS strategy.7 In addition, over the last year, COVID-19 has upended the world in fundamental ways that have affected the HIV response and have important implications for future directions of global health more broadly. Institutionally, PEPFAR awaits the nomination by the President of a new Coordinator, is preparing a new five-year, Congressionally-mandated strategy and has released principles and a vision for this strategy (see Table 1)8 ,9 and, in two years, will be considered by Congress for reauthorization (initially authorized in 2003, the program has been reauthorized three times, the most recent of which extends through 2023) (see Table 2).10

| Table 1: Key Elements of Current & Forthcoming PEPFAR Strategies |

| PEPFAR Strategy for Accelerating HIV/AIDS Epidemic Control (2017-2020) | Guiding Principles for the Next Phase of PEPFAR (Released December 2020) | PEPFAR Strategy: Vision 2025(September 2021 “2.0” Draft) |

- Focused on achieving epidemic control in 13 high-burdened countries, with ultimate goal of ending the HIV epidemic

- Aligned with UNAIDS 90-90-90 framework

- Action steps:

- Accelerate optimized HIV testing and treatment strategies

- Expand HIV prevention

- Use epidemiologic and cost data to improve partner performance and increase program impact

- Renew engagement with faith-based organizations and private sector

- Strengthen policy and financial contributions by partner governments

| - Focused on ending AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 (Sustainable Development Goal 3)

- Key principles:

- Deliver inclusive, people-centered HIV prevention and treatment services

- Support resilient and capacitated partner country health and community systems, communities, and local partners

- Partner for greater impact, burden sharing, and sustainability

| - Vision to “achieve sustained epidemic control of HIV by supporting equitable health services and solutions, enduring national health systems and capabilities, and lasting collaborations”

- Aligned with UNAIDS Global AIDS Strategy 2021-2026 and 95-95-95 framework, as well as post-2022 Global Fund Strategy

- Under strategy, PEPFAR aims to ensure that supported countries have, by 2025:

- Reached UNAIDS 95-95-95 treatment targets for all populations; sustain progress in countries that have already achieved targets

- Reduced new HIV infections, particularly in key populations, adolescent girls and young women, key populations, children

- Institutionalized data use, systems, and community-led approaches in place to monitor and address new infections in key populations and younger populations

- Made significant gains toward addressing societal challenges that impede HIV progress, including stigma and discrimination and gender-based inequalities

- Developed benchmarks that support enabling policies and systems in countries to increase domestic capacity to deliver services

|

| SOURCES: U.S. Department of State, “Strategy for Accelerating HIV/AIDS Epidemic Control (2017-2020),” 2017; U.S. Department of State, “Guiding Principles for the Next Phase of PEPFAR,” 2020; U.S. Department of State, “Draft Overview – PEPFAR Strategy: Vision 2025,” September 2021. |

| Table 2: PEPFAR Legislation |

| Full Title | Common Title | Public Law # | Years |

| United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act of 2003 | “The Leadership Act” | P.L. 108-25 | FY 2004 - FY 2008 |

| Tom Lantos and Henry J. Hyde United States Global Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Reauthorization Act of 2008 | “The Lantos-Hyde Act” | P.L. 110-293 | FY 2009 - FY 2013 |

| PEPFAR Stewardship and Oversight Act of 2013 | “The PEPFAR Stewardship Act” | P.L. 113-56 | FY 2014 - FY 2018 |

| PEPFAR Extension Act of 2018 | “The PEPFARExtension Act” | P.L. 115-305 | FY 2019 - FY 2023 |

At the same time, the fight against HIV/AIDS is far from over. In 2020, 1.5 million people were newly infected with HIV, and the pace of decline in new HIV infections has slowed.11 HIV remains the number one cause of death among those ages 15 to 49 in sub-Saharan Africa, is the number one cause of death among women of reproductive age worldwide, and, more broadly, is a leading cause of death globally.12 There are still many countries, including PEPFAR countries, which have fallen short of key global HIV targets.13 ,14 Moreover, funding to address HIV in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has stagnated at levels that are below estimated need,15 threatening further progress.16

At this inflection point for PEPFAR and the broader fight against HIV, this policy brief explores key issues and questions regarding PEPFAR’s future that, depending on how they are addressed, could shape the program’s long-term vision, goals, strategies, measures of success, and implementation moving forward, as well as the future of the broader global HIV response. Eight key interrelated issues facing policymakers, PEPFAR leadership, and others were identified. These are explored in greater detail below, providing background and context and elaborating on key strategic choices confronting PEPFAR in the coming years:

- Addressing the short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on PEPFAR and the HIV response.

- PEPFAR funding and bipartisan support.

- PEPFAR’s geographic footprint, service portfolio, and population focus.

- The role of community and civil society in PEPFAR and the HIV response.

- PEPFAR, epidemic control, and the long-term sustainability of the HIV response.

- PEPFAR’s role in global health security and broader health systems strengthening.

- PEPFAR and the Global Fund.

- PEPFAR’s structure and location within the U.S. government’s global health architecture.

(Back to top)

Issues & Questions

1. Addressing the short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19 on PEPFAR and the HIV response

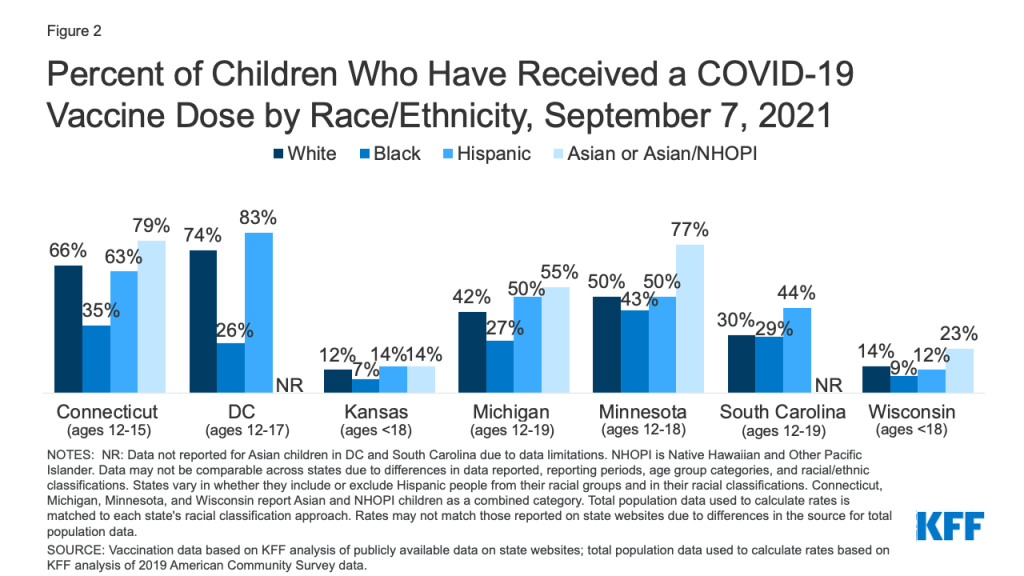

COVID-19 continues to have profound effects in the LMICs that receive PEPFAR support, where vaccination rates are markedly lower than in the U.S. (Figure 2).17 Although rates of reported COVID-19 cases and deaths are lower in sub-Saharan Africa than in many other parts of the world, some countries in the region have been harder hit.”18 Additionally, COVID-19 control measures have pushed the region into its first recession in 25 years, deepening poverty, increasing vulnerability, and challenging national budgets.19 While COVID-19 accelerated uptake of key innovations that PEPFAR has long championed, it has also presented the program with new challenges and strategic choices.

As COVID-19 emerged as a worldwide emergency, national and localized lockdowns and social distancing mandates swiftly made impossible the face-to-face encounters on which HIV services have long relied, such as clinic visits, prevention counseling, and community outreach. During the early phases of the pandemic, PEPFAR documented disruptions in HIV services, particularly for prevention, including HIV testing, voluntary male medical circumcision (VMMC), and its DREAMS initiative serving adolescent girls and young women.20 ,21 The World Health Organization,22 UNAIDS,23 and the Global Fund24 ,25 also reported service disruptions as a result of COVID-19. Beyond these direct impacts on HIV programs, indirect effects of COVID-19 could also affect the fight against HIV, including a rising incidence of gender-based violence;26 broader impacts on health systems,27 many of which were already under-resourced before COVID-19; and significant and ongoing economic hardship and financial risk28 in many of the countries in which PEPFAR works, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa.29

In one aspect of the HIV response – preserving access to HIV treatment services – action by PEPFAR leadership, as well as the Global Fund,30 appears to have minimized service disruptions or limited their duration.31 Shortly after the emergence of COVID-19, PEPFAR leadership issued guidance to the field that has been regularly updated, with a particular focus on ensuring continuity of care, providing program flexibility, and leveraging PEPFAR’s infrastructure to respond to COVID-19.32 PEPFAR has accelerated the use of strategies to minimize disruption and promote continuity of HIV services, such as multi-month dispensing of antiretrovirals and decentralized distribution of HIV self-testing kits; implemented new strategies, such as telemedicine; and allowed for some program flexibility in reporting requirements, staffing, and funding re-allocation.33 ,34 ,35

PEPFAR data for many countries indicate that, thus far, there has been no decline in the number of people accessing HIV treatment services, although disruptions in HIV testing services caused declines in the number of people newly initiating HIV treatment in many settings in the first year of the pandemic.36 A recent analysis of results in six PEPFAR countries found that the level of HIV treatment interruption was actually lower during lockdowns in five of the six countries (all but Botswana), compared to pre-lockdown levels, and that the lower rate of treatment interruption persisted after lockdowns were removed.37 Disruptions to HIV prevention services, however, were more severe and longer-lasting in many countries.38

PEPFAR’s capacity to recover ground lost as a result of COVID-19 received an important boost in March of this year, when the latest COVID-19 emergency relief bill passed by Congress39 provided the program with $250 million (Congress also provided $3.5 billion in emergency funding to the Global Fund), and PEPFAR has begun to identify how it will use these funds.40 In its National Strategy for the COVID-19 Response and Pandemic Preparedness, the White House has also said that it will seek to mitigate the secondary impacts of COVID-19 on global health programs.41 Whether these efforts will be sufficient to address the short and long-term effects of COVID-19 on the HIV response in PEPFAR countries remains to be seen, and it will likely take time to fully assess and understand the implications.

Key questions:

- Will COVID-19 set back PEPFAR’s progress and if so, to what extent? Are there specific PEPFAR countries, or populations within countries, that are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19’s impact?

- Should PEPFAR adjust its program targets to account for existing and potential effects of COVID-19 given challenges in vaccine access and concerns about a third wave? What actions can PEPFAR take to support countries in making up any ground lost during COVID-19, particularly on the HIV prevention front?

- Will PEPFAR’s emergency funds from Congress be sufficient to address the primary and secondary impacts of COVID-19 on the HIV response? How flexible will these funds be?

- Should PEPFAR be more directly involved in providing COVID-19 vaccines in the countries in which it works?

- To what extent should Congress and the administration explore broader economic relief to aid these countries in their HIV response?

- How did PEPFAR’s existing authorities affect its early response to COVID-19? Are adjustments needed to enhance its ability to respond to the lasting effects of COVID-19, future pandemics, or other shocks?

- Are there ways for PEPFAR and the Global Fund to more effectively leverage each other’s strengths, resources, and reach to respond to COVID-19 and minimize the impact on HIV, as well as TB and malaria?

(Back to top)

2. PEPFAR funding and bipartisan support

Future funding levels for PEPFAR will, in many ways, structure and affect its broad direction, including many of the looming programmatic and policy decisions highlighted in this brief. As a discretionary federal program, PEPFAR depends on annual appropriations from Congress, which are not guaranteed nor tied to the number of people in need of services or the cost of those services. While the creation of PEPFAR in 2003 heralded significant increases in U.S. HIV funding to LMICs, PEPFAR funding has been mostly stagnant for more than a decade, remaining at approximately the same level in FY 2021 as in FY 2011.42 ,43 President Biden’s first budget request to Congress, released on May 28, 2021, would keep the program at this same level in FY 2022 (see Figure 1).44

The flattening of PEPFAR funding over the past decade has occurred even as the number of people needing HIV treatment has increased and as new infections remain high. Although PEPFAR has managed to expand the number of people receiving HIV treatment services, largely through programmatic efficiencies and a pipeline of funding, the potential for further coverage gains without increased funding is uncertain. PEPFAR’s once robust funding pipeline – funding available, but not yet spent – has diminished over time, and its ability to achieve greater program efficiencies is unclear. Given that millions of people in LMICs had yet to obtain antiretroviral therapy in 2020,45 potential programmatic efficiencies on their own, by PEPFAR or others, will be insufficient to close the still-substantial HIV treatment gap (though it should be noted that the U.S. government has, in the past, stated that it will maintain antiretroviral treatment for all of those currently on treatment through PEPFAR support).46 ,47

In addition, our analyses have shown that other donors have reduced their funding for HIV in recent years, forcing an increased reliance on the U.S. government and calling into question the ability of the global community to sufficiently scale up the HIV response (Figure 3).48 While some countries that receive PEPFAR support have made strides toward mobilizing domestic resources to complement U.S. support – for example, South Africa, home to the largest number of people living with HIV, covers roughly 80% of HIV-related costs through domestic outlays49 – domestic expenditures on HIV globally have also begun to plateau.50 Moreover, even small reductions in donor assistance for HIV would be hard for many LMICs to absorb.51 This is now all the more challenging given the impacts of COVID-19 on the economies of many countries that receive PEPFAR support, at least in the near term.52

Whether funding for PEPFAR will be increased, or even sustained, will in part depend on its ability to maintain bipartisan support,53 which has been one of its hallmarks to date. An unprecedented initiative launched by a Republican president, PEPFAR has been supported by both parties and multiple congresses and administrations over time, as well as a broad and diverse base of non-governmental organizations and advocates. As a result, PEPFAR has remained largely unaffected by the increasingly polarized and partisan environment. This support has been aided by the program’s clear, singular focus on HIV, its reliance on specific goals and metrics, and its evidence of impact.54 How strongly PEPFAR’s bipartisan support persists, as well as the feasibility of more or even stable funding, in the future is unclear, however. Many original PEPFAR champions are no longer in Congress, and only 20% of current members were serving when the program was first authorized.55 In addition, decisions made about PEPFAR’s future directions – including whether or not its mandate is broadened to more directly address global health security or health systems strengthening, whether it is further integrated with other U.S. global health programs, or whether its structure is altered (see discussions below) – could affect support for the program. More generally, the sense of urgency around HIV seems to have diminished, with attention turning to other challenges, including but not limited to COVID-19.56

Key questions:

- Can PEPFAR stretch its current budget further to reach more people? Or would flat funding require a reduction in its scope?

- Without additional funding, what strategic choices should PEPFAR make and how should these be weighed?

- How does the larger global political and economic climate affect PEPFAR’s prospects for new funding? Will COVID-19’s impact on the economies of LMICs mean that even more HIV funding will be needed?

- If HIV funding from other sources is reduced, or increased, will it change the calculus of U.S. support?

- Will there be appetite in Congress to provide additional funding to PEPFAR? What if such funding were to come at the expense of other components of the U.S. global health portfolio?

- Were Congress to appropriate additional resources for PEPFAR, how best should they be used?

- How would a broadening of PEPFAR’s mandate, further integration of PEPFAR’s efforts with other global health programs, or a change in PEPFAR’s structure affect Congressional support?

(Back to top)

3. PEPFAR’s geographic footprint, service portfolio, and population focus

Among the main programmatic levers available to PEPFAR to address the HIV epidemic are its geographic focus, the set of interventions its supports, and the population groups it prioritizes. Decisions in these areas have reflected a variety of factors over time, including the epidemiology of HIV, new scientific advances, political and diplomatic considerations, historical HIV investments, and current funding levels.57 Going forward, many of these same factors will likely affect PEPFAR’s strategic choices in these three interrelated areas, as will new ones, including, for example, an increasing focus on addressing inequalities and promoting equity in the context of HIV and beyond.58 ,59 ,60

While PEPFAR’s bilateral funding has reached more than 100 countries since it launched, and today is provided to more than 50 countries (Figure 4),61 it has always concentrated its efforts in a smaller subset. This includes its original 15 “focus countries”,62 located primarily in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as its more recent emphasis on 13 “priority high-burden countries” for epidemic control, nine of which are original focus countries and all but one of which is in sub-Saharan Africa.63 ,64 Most of PEPFAR’s current country funding is concentrated in 10 countries,65 which together represent more than half (54%) of people living with HIV globally (Figure 5).66

At the same time, while PEPFAR’s most prominent funding footprint remains in eastern and southern Africa, the sub-region most heavily affected by HIV and where PEPFAR is widely acknowledged to have played a pivotal role in the area’s comparatively greater progress in treatment coverage and HIV incidence reduction,67 incidence has been on the rise in Eastern Europe/Central Asia (where deaths have also risen recently), Latin America, and the Middle East and North Africa.68

Going forward, PEPFAR faces a range of possible options with respect to its future geographic footprint. PEPFAR could continue to concentrate most funding and activities in the same set of countries currently prioritized as these countries work toward epidemic control. This would promote continuity and predictability but might not neatly map to where the need is greatest or where other donor actions may leave gaps. Alternatively, PEPFAR could further narrow its scope to a smaller set of countries, which could help to drive impact or allow greater focus within particularly hard hit or challenging areas. However, this approach might require a scale down in other countries and, again, may not be responsive to changing epidemiological trends. Finally, PEPFAR could seek to increase investments elsewhere to maximize responsiveness to an ever-evolving epidemic, such as directing resources to countries facing the loss of other donor support (e.g., middle-income countries that are no longer eligible for Global Fund support), experiencing increasing HIV rates among key populations, and/or other acute challenges such as conflict or famine. How these decisions are made will depend on multiple factors, including future funding, without which any decision to change geographic focus could become a zero-sum game, with real risks to HIV outcomes (though as noted above, the U.S. government has stated that it will maintain antiretroviral treatment for all those it supports).

PEPFAR’s service mix

PEPFAR currently channels just over half (52% in 2020) of its planned funding to HIV treatment, 16% to care, 15% to prevention, 6% to testing, and the remainder (11%) to governance, management, and operations.69 PEPFAR’s current service mix is the result of years of shifting funding mandates by Congress as well as the evolution in standards of care and introduction of new interventions. PEPFAR’s original legislation required that at least 55% of bilateral funds be spent on treatment70 and that at least 33% of prevention funds be spent on abstinence-until-marriage (ABC) programs, among other requirements. After criticism of these earmarks,71 ,72 Congress somewhat relaxed these requirements in 2008.73

While HIV treatment remains the single greatest area of expenditure for PEPFAR, the program has supported an increasing range of prevention interventions over time. Especially noteworthy is the creation by PEPFAR in 2015 of the DREAMS initiative, which links biomedical, behavioral, and structural approaches to prevent new HIV infections among adolescent girls and young women in 15 countries.74 PEPFAR reports that it has invested nearly $1 billion in DREAMS.75 A recent review found that DREAMS programs have reached millions of adolescent girls and young women, elevated global attention to the HIV agenda for these populations, and contributed to a decline in new HIV infections among adolescent girls and young women in districts where DREAMS programs are operating.76

However, the stubbornly high global rate of new HIV infections has led UNAIDS to call for a substantial strengthening of investments in HIV prevention efforts and structural interventions to address the factors that contribute to HIV vulnerability and impede service utilization.77 The case for bolstering HIV prevention has been underscored by the disruptions in HIV prevention services caused by COVID-19, as well as by the pipeline of new prevention technologies that are likely to come on line soon, such as long-acting injectable pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and vaginal dapivirine rings. Yet, at the same time, the HIV treatment agenda remains unfinished, as more than one in four of all people living with HIV worldwide were not receiving antiretroviral therapy in 2020 and one-third were not virally suppressed.78

Lastly, although PEPFAR retains a singular focus on HIV, the program has also provided services to address co-morbidities frequently experienced by people living with HIV, including tuberculosis, cervical cancer, viral hepatitis, and cryptococcal meningitis. In addition, it has started to address some chronic conditions faced by people with HIV as they age, but there is an open question about how much it should emphasize these other areas in the future.

As with possible changes in PEPFAR’s geographic footprint, PEPFAR could choose to rebalance its portfolio mix, as long as it complies with Congressional mandates (though Congress could also choose to relax or change some of these mandates in the future). This could include a greater emphasis on prevention programming, such as increasing support for PrEP; scaling-up support for structural interventions; devoting more resources to health systems strengthening, including for health care workers, in support of HIV interventions; and/or more proactively planning for the incorporation and rapid diffusion of new technologies on the horizon (e.g. vaginal microbicides, long-acting PrEP), which is one objective in PEPFAR’s draft vision for 2025.79 Changes in the broader environment, such as further reductions in the unit costs of antiretroviral therapy, could conceivably aid PEPFAR in freeing up resources for the scale-up of prevention and other non-treatment programming, or for treating additional people.

PEPFAR’s population focus

As with PEPFAR’s geographic and service mix, PEPFAR’s population focus, particularly for prevention efforts, has evolved over time, largely reflecting the relaxation of legislative mandates and changing political views. With much of its early prevention programming focused on promoting an ABC (“abstinence, be faithful, use condoms”) approach and reducing heterosexual transmission, there was limited attention to high-risk key populations such as men who have sex with men, sex workers, and injection drug users. In fact, PEPFAR’s original authorizing legislation was almost completely silent on these populations. Over time, PEPFAR has increased its focus on key populations, releasing specific guidance on injection drug users (in 2006) and men who have sex with men (in 2011),80 supporting the development of evidence-based estimates of the size of key populations in countries, and launching a Key Population Implementation Fund.81

Notwithstanding this evolution, programming for key populations has never been a central pillar of PEPFAR’s work in most countries. In FY 2021, planned PEPFAR funding specifically identified to address key populations totaled $269.8 million, or just 6% of the total.82 There have been calls for PEPFAR to further increase its focus on key populations, including by creating a DREAMS-type program for key populations.83 This stems from both the unique challenges and barriers they face, including discrimination, stigma, and criminalization in their own countries, as well as evidence that high-risk key populations and their partners are now driving the global HIV epidemic, accounting for 62% of new HIV infections in 2019.84 A new series of papers highlights the importance of enhancing efforts to address HIV among key populations in Africa, who will “increasingly become the face of AIDS” on the continent.85

In addition, although PEPFAR’s authorizing legislation prioritized programming for women and girls, the challenge of meeting their needs and importance of increasing PEPFAR’s focus on women and girls has been identified throughout PEPFAR’s history.86 ,87 ,88 Women, particularly young women and girls, continue to be at high risk for HIV and face unique challenges. In 2020, women accounted for 51% of new HIV infections globally, including 63% in sub-Saharan Africa.89 Adolescent girls and young women are particularly vulnerable, with those in sub-Saharan Africa estimated to have an HIV risk that is 4.5 times higher than men their own age.90 These challenges helped to drive the creation of the DREAMS initiative in 2014. As with calls to increase the focus on key populations, some have also called for more funding and attention to the needs of adolescent girls and young women by PEPFAR as well as through broader U.S. programming.91

Finally, there have been similar calls for PEPFAR to increase attention to and funding for children,92 as well as for men and boys. PEPFAR has been a key provider of HIV services for children, supporting treatment services to nearly 700,000 children living with HIV and providing care and support to 6.7 million orphaned or made vulnerable by HIV as well as their caregivers.93 However, there are significant gaps in access,94 particularly for antiretroviral treatment, with only 54% of the 1.4 million children living with HIV diagnosed and on treatment in 2020, compared to 74% of adults.95 Data also show that men and boys lag in their uptake of HIV testing and treatment, posing risks for themselves and their partners. While PEPFAR has developed specific programs targeting men and boys, including through the MenStar Coalition96 with private sector partners, and is the largest funder of VMMC in the world, it has also been criticized97 for not including men and boys more directly in DREAMS programming.

Going forward, as with its geographic footprint and service mix, PEPFAR faces key strategic questions about whether it should expand or shift its population focus in any way. These decisions depend in part on funding, but also the extent to which PEPFAR has comparative advantages relative to other donors or country governments in addressing the needs of certain population groups, such as those who face discrimination or even criminalization by their own governments.

Key questions:

- Should PEPFAR expand, narrow, or otherwise change the countries and regions where it works? If so, what should be the factors or criteria that determine PEPFAR’s future geographic footprint? How important will future funding levels be to PEPFAR’s ability to alter its geographic footprint?

- How, if at all, should PEPFAR’s HIV service mix change? How might PEPFAR expand its prevention services while preserving and continuing to maintain or even scale up treatment access and improving rates of viral suppression? To the extent PEPFAR opts to expand its prevention services, which prevention interventions should be prioritized and which target populations?

- Should PEPFAR increase its focus on addressing co-morbidities and chronic conditions among people with HIV? Does it have a mandate to do so?

- How can PEPFAR best be prepared to rapidly diffuse new technologies once they are available?

- Are there priority populations that warrant intensified assistance from PEPFAR? If so, which ones?

- Should PEPFAR create a DREAMS-like initiative for key populations or otherwise intensify its assistance for programming to address the HIV prevention and treatment needs of key populations? What is PEPFAR’s comparative advantages with respect to key population programming?

- To what degree would an increased focus on key populations, or other population groups, be tied to decisions regarding PEPFAR’s geographic footprint? What trade-offs need to be considered?

- To what extent should PEPFAR incorporate equity goals into its HIV response and decisions about who to serve?

- How should actions or policies of other donors and country governments be taken into account in PEPFAR’s decision-making regarding its geographic, service, and population emphases in the future?

(Back to top)

4. The role of community and civil society in PEPFAR and the HIV response

Since the onset of the HIV epidemic, communities, including people living with HIV, have played a key role in the HIV response – as advocates, providers of services, and accountability watchdogs.98 Communities bring to the table unique perspectives on their needs and on the most effective public policies and service delivery strategies, underscoring the importance of community engagement in the planning and implementation of HIV programs.99 The integral involvement of civil society in the HIV response has distinguished it from other areas of global health and development, and this has been the case for PEPFAR as well.

The participation of civil society in PEPFAR’s policy development and programming has a long history, one which has increased and become more formalized over time. While PEPFAR’s early annual reports to Congress identified the importance of civil society, the program’s 2008 reauthorization specifically required PEPFAR to include civil society in the development of new “compacts” at the country level, and PEPFAR’s subsequent Partnership Framework Guidance reflected this.100 ,101 In 2013, for the first time, PEPFAR formally included civil society in the annual process for developing the Country Operational Plans (COPs) that guide PEPFAR support at the country level, with the FY 2014 COP guidance specifying that PEPFAR country teams must include a separate supplemental narrative documenting how civil society has been involved in COP development, comments made by civil society, and the ways in which the country teams have considered these comments as part of COP planning.102

This inclusion of civil society has resulted in adjustments in PEPFAR’s guidance and influenced country plans. At the level of the Office of the Global AIDS Coordinator (OGAC), for example, civil society input led PEPFAR to change its COP guidance to address concerns about the delivery of index testing (the offer of testing to partners or family members of people living with HIV)103 and to develop further guidance on safe and ethical ways to deliver this service.104 At the country planning level, a recent analysis found that nearly 500 civil society recommendations were either fully or partially incorporated into PEPFAR annual country workplans during the COP 2020-2021 planning process.105 In addition, community involvement in COP development has been cited as an important factor in the implementation of innovations in HIV treatment programming in Malawi, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.106 Finally, civil society groups successfully advocated to have PEPFAR, and the Global Fund, adopt and support “community-led monitoring” (CLM), a process by which civil society groups are directly involved in data collection on HIV service quality and access primarily from actual beneficiaries of those services, and PEPFAR COP guidance now requires countries to establish CLM.107 Despite these efforts, community groups continue to document challenges in access and quality at the country level, suggesting that this work is ongoing.

In addition to strengthening PEPFAR’s immediate efforts, the inclusion of community and civil society could be important for the longer-term sustainability of programs in countries. Civil society engagement and strengthening have been found to be key ingredients in successful country transitions from donor assistance.108 ,109 ,110 As experience during COVID-19 has underscored, community organizations and networks are able to reach populations not always well served by health facilities and play a critical role in preserving service access during crises.111 Sustaining community-led responses over time will likely depend on transitioning the funding of community infrastructure from donors to domestic governments through mechanisms such as social contracting, whereby governments provide support to community groups for performing essential health functions.112

There may also be lessons to be learned from PEPFAR’s experience for other U.S. global health and development programs on how to include civil society more formally in planning and programming efforts, as well as efforts to promote sustainability.

Key questions:

- How can PEPFAR build upon and sustain its support for community-led HIV responses? Are there other ways to augment community involvement, particularly at the country level?

- Should PEPFAR, and the U.S. government, engage HIV civil society more directly in monitoring human rights and governance challenges in the countries in which it works?

- How can communities be engaged over the long term to inform, assess, and monitor PEPFAR when and if it seeks to reduce or discontinue assistance in particular countries or settings?

- How might lessons learned from PEPFAR’s inclusion of civil society and support for community-led responses inform and strengthen other U.S. government health and development programs?

(Back to top)

5. PEPFAR, epidemic control, and the long-term sustainability of the HIV response

Although PEPFAR was designed from the outset as an emergency response, the importance of building sustainable capacity in countries was recognized as a priority at the early stages of the program. Capacity building for sustainability was included in PEPFAR’s original authorizing legislation,113 its first five-year strategy,114 and the Institute of Medicine’s early assessment of the program.115 As the Institute of Medicine (IOM) found, “For continued progress toward its 5-year targets and longer-term goals, PEPFAR should transition from a focus on emergency relief to an emphasis on the long-term strategic planning and capacity building necessary for sustainability.”116 By the time PEPFAR was reauthorized in 2008, there was a specific emphasis on country ownership and health system strengthening.

PEPFAR has used different models to enhance country ownership and sustainability over time, including “Partnership Frameworks,” required by the 2008 reauthorization and developed with 19 countries and two regions between 2009 and 2012,117 and “Country Health Partnerships”,118 created in 2013 and used with several countries.119 ,120 In addition, PEPFAR developed a “Sustainability Index and Dashboard (SID)” in 2015 that all country teams complete.121 In 2018, PEPFAR announced that it would direct at least 70% of its funding to host country governments or local organizations by the end of 2020, although that benchmark has not yet been met.122 ,123 PEPFAR’s draft strategic vision for 2025 includes a goal to “Build Enduring Capabilities” which includes developing benchmarks to, among other things, ensure “that countries and communities can lead with the capacity to deliver prevention and treatment services through domestic systems.”124

Still, how best to define and sustain long-term success in any recipient country remains an important challenge for PEPFAR, as well as for other HIV donors. While epidemic control has been identified as a critical program target, along with reaching the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals,125 PEPFAR acknowledges that “[t]his definition of epidemic control does not suggest near-term elimination or eradication of HIV, as may be possible with other infectious diseases, but rather suggests a decline of HIV-infected persons in a population, achieved through the reduction of new HIV infections when mortality among [people living with HIV] is steady or declining, consistent with natural aging” (see Table 3 for key global HIV targets and status in PEPFAR countries).126

| Table 3: Progress Toward Global HIV Targets in PEPFAR Countries |

| Target | Definition | PEPFAR Countries Meeting Target in 2020 (out of 53) |

| Know HIV Status | First of UNAIDS “90-90-90” targets established in 2014 and expired in 2020 – 90% of people with HIV know their status. | 13 (25%) |

| Receiving ART | Second “90” – 90% of people who know their status are on treatment. | 14 (26%) |

| Suppressed Viral Loads | Third “90” – 90% of people on treatment have suppressed viral loads. | 13 (25%) |

| PEPFAR’s Epidemic Control Target (Incidence-to-Mortality) | Ratio of number of new HIV infections to number of people infected with HIV who die (from any cause). When ratio is greater than one, or when there are more new infections than deaths, size of the population of people living with HIV grows; when less than one, size of population shrinks. | 18 (34%) |

| HIV Incidence per 1,000 | Number of new HIV infections per 1,000 population. Global HIV incidence target is <1%. | 41 (77%) |

| Incidence-to-Prevalence | Ratio of number of new HIV infections and number of people living with HIV within a population to measure average duration of time a person lives with the disease. Benchmark for epidemic control is a ratio of 3%. When the number of new infections is less than 3%, total population of people who live with HIV will eventually decline. | 20 (38%) |

| NOTE: HIV epidemiological data is for all ages unless otherwise specified.SOURCES: KFF analysis of data from: U.S. Department of State, “Where We Work — PEPFAR” webpage, https://www.state.gov/where-we-work-pepfar/; UNAIDS, AIDSInfo database, accessed August 2021; UNAIDS, Global AIDS Update 2021, July 2021; UNAIDS, “Ratio of new HIV infections to number of people living with HIV improving,” April 2020; UNAIDS, “Making the End of AIDS Real: Consensus building around what we mean by epidemic control,” October 2017. |

With respect to PEPFAR assistance, it is not yet clear what the scope and nature of U.S. support might be after a country achieves epidemic control or other program targets, and how best to sustain HIV treatment and prevention programs and leverage surveillance systems going forward and guard against shocks or respond to setbacks that might occur, as in the case of COVID-19. Additionally, some of the elements needed to achieve and sustain gains are beyond the control of the U.S. government, such as adequate national investments in health, the capacity for which is heavily affected by macroeconomic conditions and the effectiveness of national governance.

Ultimately, promoting sustainability and country ownership is a major challenge, given the complexity of the HIV epidemic and the larger political and economic climate in recipient countries. Despite its efforts to promote sustainability and country ownership, PEPFAR does not have formal transition or graduation plans, unlike the Global Fund127 and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance,128 for example, each of which have specific graduation criteria and requirements for domestic co-financing. Whether PEPFAR should consider instituting a formal transition or graduation plan, specific criteria for determining when and at what pace to draw down financial or other support, or requirements for co-financing are key strategic questions for the future. If it were to pursue such a strategy, there are important lessons to be learned from the U.S. family planning program and other health areas, as well as the experiences of the Global Fund and Gavi, including the length of time needed and the challenges faced by more marginalized populations.129 ,130 ,131

Moreover, the continued heavy reliance of many countries on PEPFAR support (in many cases, more so than in other health areas) poses another challenge to long-term sustainability. According to the latest data on HIV expenditures (2017-2019), PEPFAR accounted for 86% of all HIV-related spending in Tanzania, 73% in Angola, 66% in Mozambique, 57% in Zambia, 56% in Lesotho, and 50% in Malawi.132 With some notable exceptions, governments in countries receiving PEPFAR aid have had difficulty allocating substantially greater domestic resources for HIV services to complement and leverage PEPFAR assistance, even before COVID-19. Factors that have contributed to limited domestic contributions include challenges mobilizing sufficient domestic resources to address HIV; multiple, simultaneous pressures to take on more of their HIV responses, as well as more of their responses to other health issues, from other donors; weak health systems; and difficulty in instituting social insurance schemes which could help to promote access.133 The effects of COVID-19 in LMICs – increasing hunger, poverty, unemployment, and the need for government assistance at the same time that the pandemic’s economic shocks have reduced government revenues – may delay even further the domestic investments in health and HIV that will be needed for long-term sustainability.134

Key questions:

- How else can PEPFAR promote long-term sustainability in the countries in which it works? How should such considerations be adjusted or tempered as the result of the COVID-19 pandemic?

- For countries that achieve epidemic control, how might PEPFAR assistance evolve? Should the upcoming reauthorization of PEPFAR specify criteria or mechanisms for transitioning PEPFAR assistance in countries that achieve or approach epidemic control? What steps are needed to ensure that gains in the response can be sustained in high-performing countries? What is the risk that some might see “epidemic control” as an endpoint?

- Should PEPFAR develop clear metrics or “graduation” criteria to guide country-specific transitions from PEPFAR support? If so, what should these metrics consist of and how might PEPFAR avoid creating unintended incentives that penalize countries that are doing well?

- Should PEPFAR implement clear co-financing requirements for recipients of PEFPAR support?

- As PEPFAR explores ways in which to increase recipient country ownership of the HIV response, what safeguards should be included to ensure that HIV outcomes do not suffer and that certain groups, particularly key populations, are not left behind?

- How should PEPFAR’s efforts to promote long-term sustainability of the HIV response be coordinated with other U.S. government efforts and those of other donors, the private sector, and communities?

(Back to top)

6. PEPFAR’s role in global health security and broader health systems strengthening

In large part because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is growing attention to scaling up U.S. global health security efforts and creating more resilient health systems.135 This is shaping up to be a major global health focus of the Biden administration.136 On his first day in office, President Biden issued an Executive Order on “Organizing and Mobilizing the United States Government to Provide a Unified and Effective Response to Combat COVID-19 and to Provide United States Leadership on Global Health and Security.”137 This was followed shortly thereafter by a National Security Memorandum on “United States Global Leadership to Strengthen the International COVID-19 Response and to Advance Global Health Security and Biological Preparedness.”138 In addition, several bipartisan global health security bills have been introduced in Congress calling for more funding and U.S. action.139

It is still unclear, however, what an increased emphasis on global health security will mean for PEPFAR, as well as for the other core, longer-standing components of the U.S. global health portfolio, and this growing focus poses both opportunities and risks. On the one hand, PEPFAR already contributes significantly to health systems strengthening efforts, including support for many of the key elements of pandemic preparedness which, combined with its large geographic footprint and diplomatic engagement, may make it uniquely situated among U.S. global health programs to play a broader role in this area. For example, PEPFAR reports that it has supported 3,000 laboratories, including 28 national reference laboratories, 70,000 health care facilities, and 290,000 health care workers, and invests almost one billion dollars each year in health systems.140 In addition, as the first and largest U.S. global health program specifically designed to address a pandemic, PEPFAR could offer key lessons for broader U.S. pandemic preparedness efforts and potentially be integral to such efforts. On the other hand, an increased focus on broader health security could conceivably crowd out other global health investments and reduce the stature of the PEPFAR program and emphasis on HIV when tremendous need still exists.

As mentioned above, infrastructure components built by or strengthened through PEPFAR investments – specifically those focused on preservation of HIV treatment services – rapidly pivoted in 2020 to address COVID-19 and continue to play important roles in national COVID-19 responses.141 PEPFAR-supported laboratories provide diagnostic testing for COVID-19; health care workers hired through HIV investments shifted to manage COVID-19 as well; HIV clinical sites, many of them closed during lockdowns, were repurposed to care for COVID-19 patients; and strategic information systems strengthened through PEPFAR investments proved critical for tracking COVID-19.142

This is not the first time that PEPFAR and other HIV investments have contributed to managing a serious health emergency, as was seen in the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014-2015.143 ,144 Still, whether and how PEPFAR’s expertise and reach will be leveraged to address a more robust U.S. global health security engagement, and health systems more generally, remains unclear and depending on the approach could either strengthen or dilute HIV efforts.

Key questions:

- Will an increasing emphasis on global health security and pandemic preparedness pull attention away from PEPFAR and the fight against HIV or can PEPFAR become an integral contributor to these efforts? Does a program largely focused on a single disease support or complicate global health security efforts?

- What are PEPFAR’s comparative advantages for responding to COVID-19 and other pandemics?

- Should PEPFAR be more intentional about identifying opportunities to build out from the program’s platform to strengthen pandemic preparedness and response? Are changes needed in PEPFAR’s authorization to better leverage PEPFAR’s comparative advantages with respect to pandemic preparedness and response? Should global health security and pandemic preparedness become a greater part of PEPFAR’s future mandate?

- How can PEPFAR’s contributions to health systems strengthening and pandemic preparedness be better quantified and accounted for?

- How can the U.S. government build on the PEPFAR platform for other global health and development efforts, including global health security, without diminishing the HIV response? Are there marginal investments that could be made to do so?

(Back to top)

7. PEPFAR and the Global Fund

The Global Fund, founded in 2002, is an independent multilateral financing entity designed to raise significant resources and intensify efforts to end the AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria epidemics. The U.S. has played an integral role in the Global Fund since its inception by providing the Global Fund with its founding contribution, serving as its single largest donor, and being active in the organization’s governance and oversight.145 The Global Fund has been called the “multilateral component” of PEPFAR146 and together, the two account for most (82% in 2019) international funding provided to address HIV in LMICs.147

PEPFAR and the Global Fund work quite differently, however.148 PEPFAR, for example, uses a donor-driven model, driving decisions from Washington, D.C. to the country-level, and the U.S. government has a significant presence on the ground in many of the countries in which it works. By contrast, the Global Fund relies on country-driven proposals, and, as a financing mechanism, does not have any programming presence in countries. PEPFAR uses an annual COP planning process while the Global Fund’s Country Coordinating Mechanism development process is on a three-year cycle. In some cases, the differences between PEPFAR and the Global Fund have been complementary. The Global Fund has helped to expand PEPFAR’s reach to many more countries and to leverage additional donor resources. PEPFAR has provided on-the-ground technical and other support for Global Fund programs. Additionally, in many of the countries that receive funding from both, PEPFAR and the Global Fund finance different components of the HIV response – the Global Fund is generally the largest funder of HIV commodities in PEPFAR countries while PEPFAR funds many of the associated services needed to support the delivery and use of commodities, for example.149

Given how important both PEPFAR and the Global Fund are to the HIV response, there may be opportunities for the U.S. government to rethink and strengthen their relationship going forward, including through more proactive and strategic coordination, particularly given concerns about future financing for HIV. For example, both the Global Fund and PEPFAR are in the process of developing new strategic frameworks, which may provide a natural opportunity to enhance strategic alignment between the two programs. PEPFAR’s draft vision for 2025 indicates that it will seek to closely coordinate with the Global Fund Strategy to “optimize complementarity, value for money, and impact.”150 Specific areas that might be more closely coordinated include planning cycles, monitoring systems, and guidance documents, in part to reduce reporting burdens on countries and partners. Other areas that could be explored for further coordination and alignment include a more explicit division of labor and/or financing for specific HIV services (e.g., commodities, labs, workforce, etc.) in countries where both are present; leveraging PEPFAR’s expertise to assist the Global Fund in strengthening the quality, timeliness, and strategic use of program data; and more closely planning regarding support for countries transitioning off of Global Fund financing, particularly since the list of these countries is known several years in advance.

Key questions:

- What factors should the U.S. government use to determine the optimal balance of U.S. funding between PEPFAR and the Global Fund, particularly in the long term?

- Could PEPFAR and the Global Fund coordinate more closely to support countries that are transitioning off of Global Fund financing?

- Could planning cycles and strategy development be more closely aligned?

- Could there be more direct and proactive coordination regarding the division of financing for specific HIV services (e.g., commodities, labs, workforce, etc.) in countries in which both PEPFAR and the Global Fund operate?

- Can PEPFAR leverage its expertise to assist the Global Fund in strengthening the quality, timeliness, and strategic use of program data and data monitoring capabilities? Can the two work more closely together on monitoring to reduce the reporting burden on implementers?

- Can PEPFAR and the Global Fund work more directly together on mitigating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the HIV response?

(Back to top)

8. PEPFAR’s structure and location within the U.S. government’s global health architecture

When PEPFAR was first created, locating it in the State Department and providing its Coordinator with the power to oversee all U.S. global HIV investments, as specified in its authorizing legislation, marked a departure from the way in which U.S. global health programs had been structured. Prior to that point, with limited exception, global health programs, including bilateral HIV assistance, typically resided at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) [USAID and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are PEPFAR’s main implementing agencies, although several other arms of the U.S. government carry out HIV activities under PEPFAR’s coordination]. There were several reasons this unorthodox approach was taken with PEPFAR: an emergency program that linked multiple arms of the U.S. government appeared to justify an unusual organizational approach; PEPFAR’s placement at State was believed to better harness U.S. diplomacy capabilities in addition to development and public health expertise in other agencies; and situating PEPFAR at State recognized that the global HIV epidemic presented not only public health but also major human rights and national security challenges.

PEPFAR’s first five-year strategy, presented to Congress in 2004, discussed its intentional role in supporting the implementation of good policies and effective legislation, including addressing stigma and discrimination and promoting human rights.151 PEPFAR’s diplomatic role has been cited as one of its most important successes.152 ,153 ,154 ,155 PEPFAR has worked with host country governments to remove user fees for accessing health services; adopt international HIV treatment guidelines and standards of care; and address stigma and discrimination against key populations.156 ,157 ,158 ,159 Analyses have found that higher levels of PEPFAR investment are associated with greater improvements in key governance measures and that PEPFAR countries have better policy alignment with internationally recommended standards compared to other LMICs that do not receive PEPFAR support.160 ,161 ,162

Still, some have argued that at this point in PEPFAR’s evolution, the program should be moved to USAID,163 co-located with other global health efforts, to further its transition from an “emergency” program to one more focused on long-term development. Others, citing the program’s broadly recognized positive impact on the HIV response, have argued that it is important to keep the current structure, and that moving PEPFAR would present significant risks, including threatening the HIV response and diluting PEPFAR’s diplomatic role, which could have implications for country-level coordination with local governments.164 In addition, they posit that PEPFAR, by virtue of its structure, should be seen a model for other U.S. global health programs in leveraging public health, development, and diplomatic expertise for achieving desired outcomes. In addition, given the size of PEPFAR investments in numerous countries, the program has unique leverage and diplomatic impact, which could translate beyond HIV. This issue has gained new attention in the context of President Biden’s moves to shore up the U.S. global health security response, including by placing a Coordinator for the Global COVID Response and Health Security at the State Department,165 and a bipartisan global health security bill introduced in the Senate which seeks to establish a special representative for global health security and diplomacy at the State Department, to be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate.166

There are also broader conversations regarding the importance of integrating across global health programs, particularly to better reach and more effectively serve women and girls, which may have bearing on PEPFAR’s structure.167 ,168 PEPFAR’s DREAMS initiative for adolescent girls and young women is one effort to offer a more integrated approach, with HIV prevention, testing, and treatment services linked to educational assistance, economic support and community strengthening. However, the DREAMS program still faces challenges in integrating fully with other U.S. government global health and development assets. For example, as a matter of policy, PEPFAR funds cannot be used to procure contraceptive commodities, other than for prevention purposes, which must instead be funded by other U.S. programs or other donors.169 More generally, Congress funds U.S. global health programs through specific appropriations and requires reporting according to these siloes, making it difficult to integrate across programs.

Ultimately, whether or not discussions about PEPFAR’s structure or location will continue, Congressional legislation would be needed to make some of these changes, including the location of PEPFAR at State and reporting line of the Coordinator.

Key questions:

- Should PEPFAR’s statutory structure and location at the State Department be reconsidered? What are the risks of doing so? What are the opportunities? How does the administration’s increased focus on global health security and diplomacy affect these considerations?

- Are there ways to better leverage PEPFAR’s role in global health diplomacy beyond HIV? What are the opportunities to support a more “whole-of-government” approach in the U.S. government’s relations with countries that receive PEPFAR support?

- What steps are needed to improve the integration of PEPFAR with other U.S. global health and development programs? Should Congress and the administration consider elimination of some of the existing budgeting line silos or otherwise encourage reporting on integrated programming?

Conclusion

PEPFAR has made historic contributions to the health and well-being of people living in the world’s most resource-constrained countries, first starting as an emergency program with little precedent and growing to become the mainstay of the global HIV response and largest component of the U.S. global health portfolio. As PEPFAR approaches its two-decade mark, however, it is at an important inflection point and there are several key strategic questions regarding its programmatic focus and role within the U.S. government’s global health and development portfolio going forward. Key factors that have the potential to influence PEPFAR’s future include the growing emphasis on global health security (and the continuing need to mitigate the spread and impact of COVID-19 and to hasten recovery from the pandemic), the durability of bipartisan political support and its implications for program funding, how PEPFAR defines success in individual countries and promotes the long-term sustainability of national HIV responses, and the optimal relationship of PEPFAR to other global health programs. Given that the fight against HIV is far from over, decisions about PEPFAR’s future will have an outsized impact on the course of the HIV epidemic. The key strategic issues and questions posed here aim to inform these decisions.

This work was supported in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Jennifer Kates and Alicia Carbaugh are with KFF. Mike Isbell is an independent consultant. KFF’s Stephanie Oum and Anna Rouw also contributed to the brief.