The Helms Amendment and Abortion Laws in Countries Receiving U.S. Global Health Assistance

Key Facts

- The Helms Amendment, signed into law almost fifty years ago, as an amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, prohibits the use of foreign assistance to pay for the performance of abortion as a method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortion.

- In practice, the Helms Amendment has also been used to prohibit the use of federal funding for all abortions even in the circumstances of rape, incest, or risk to the life of the pregnant person, exceptions that have been allowed in other areas of U.S. international abortion law and policy.

- There has been growing debate about the Helms Amendment, with some advocates and legislators supporting efforts to clarify the application of the Helms Amendment to allow for exceptions and, more recently, to repeal it. To better understand the implications of the Helms Amendment for abortion access globally and to inform ongoing discussions, we examined abortion laws in countries that received U.S. foreign assistance, looking specifically at funding for family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH), maternal and child health (MCH), and PEPFAR.

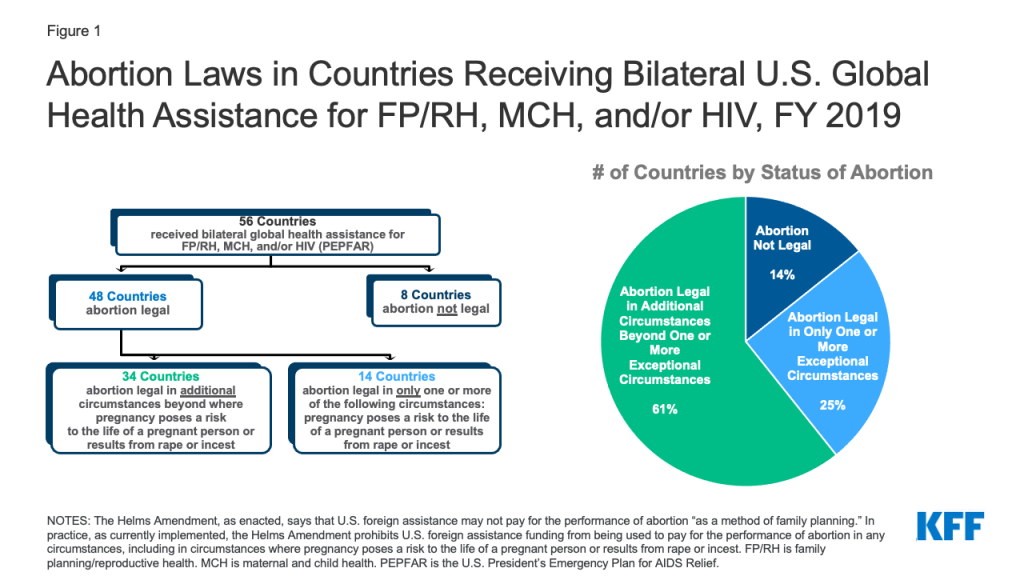

- We find that of the 56 countries receiving such U.S. global health assistance, most (86%, or 48 countries) allow for abortion in at least one circumstance.

- These 48 countries account for 95% ($4.53 billion) of U.S. global health assistance for FP/RH, MCH, and PEPFAR. Most are in Africa (30 countries). PEPFAR funding reaches the most countries (36), followed by MCH (35) and FP/RH (29).

- Of the 48 countries, 14 (or 25% of those receiving U.S. support) allow abortion in only one or more exceptional circumstances, while the remainder (34 countries) allow for abortion beyond these exceptions.

- Given that the U.S. is often the largest funder of health efforts in low- and middle-income countries, these findings suggest that the outcome of debates about the Helms Amendment stands to significantly affect access to legal abortion in a large number of countries, primarily those in Africa. Repeal of the Helms Amendment would expand the ability of U.S. global health assistance to support legal abortion in many countries, while clarifying Helms to allow such support in exceptional circumstances would also expand the ability of U.S. global health assistance to support legal abortion but in more limited circumstances.

Introduction

The Helms Amendment, signed into law almost fifty years ago, as an amendment to the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, prohibits the use of foreign assistance to pay for the performance of abortion as a method of family planning or to motivate or coerce any person to practice abortion. In practice, it has also been used to prohibit the use of federal funding for all abortions even in the circumstances of rape, incest, or risk to the life of the pregnant person, exceptions that have been allowed in other areas of U.S. international abortion law and policy, such as the Mexico City Policy when it has been in place. There has been growing debate about the Helms Amendment, with some advocates and legislators supporting efforts to clarify the application of the Helms Amendment to allow for exceptions and, more recently, to repeal it. Last year, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the FY 2022 State and Foreign Operations (SFOPS) appropriations bill without language reiterating the Helms Amendment,1 and legislation has been introduced that would permanently repeal the Helms Amendment by striking its language from the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 (see the KFF global health legislation tracker).2

Still, the prospects of repeal of the Helms Amendment are challenging. While the Biden administration has called for repeal of the Hyde Amendment (the domestic law restricting federal funding for abortion),3 its stance on Helms is unclear. It has not taken a public position on repeal, and its first budget request to Congress included the Helms language. Moreover, both chambers of Congress would have to agree to excluding Helms Amendment language from annual appropriations legislation as well as from the permanent statute, the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. Even if repealed, it would not necessarily lead to more funding for abortion, especially if U.S. funding for global health remains level.

To better understand the implications of the Helms Amendment for access to abortion services globally and to inform ongoing discussions, we examined abortion laws in countries that received U.S. foreign assistance. We sought to identify the number of countries in which abortion is legal but U.S. funding is not permitted, even in the exceptional circumstances noted above.4 While the Helms Amendment applies to all U.S. foreign assistance, we focused our analysis on assistance for family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH), maternal and child health (MCH), and HIV, through PEPFAR, since these are the technical areas of USAID’s health work to which Helms and other FP/RH restrictions “most often apply,” according to USAID.5 We placed countries receiving bilateral U.S. global health assistance in FY 2019 (the most recent publicly-available complete data) into three categories according to their abortion laws:

- abortion not legal in any circumstance;

- abortion legal in one or more of the following circumstances: where the pregnancy poses a risk to a pregnant person’s life, is the result of rape or is the result of incest; and

- abortion legal in any circumstance beyond the preceding ones (e.g., to preserve the physical or mental health of a pregnant person or for social or economic reasons).

Findings

In FY 2019, the U.S. provided bilateral global health assistance for FP/RH, MCH, and/or HIV (PEPFAR) to 56 countries. Together, funding across these three areas totaled $4.77 billion. Funding for PEPFAR and MCH was directed to the greatest number of countries (40 and 39, respectively), followed by FP/RH (35). More than half (33) of the 56 countries reached were in Africa, followed by East Asia and the Pacific (8), South and Central Asia (7), Latin American and the Caribbean (4), the Near East (3), and Europe and Eurasia (1).

Abortion is legal in at least one circumstance in almost all – 48 of 56 (or 86%) – of the countries receiving U.S. support. These 48 countries accounted for 95% ($4.53 billion) of U.S. global health assistance for FP/RH, MCH, and PEPFAR. Most were in Africa (30), and PEPFAR reached the largest number (36), followed by MCH (35) and FP/RH (29). See Figure 1 and Tables 1 and 2.

In 14 countries (25% of countries receiving U.S. support) abortion is legal only in at least one exceptional circumstance (where the pregnancy poses a risk to the life of a pregnant person, is the result of rape, or is the result of incest). These countries accounted for 34% ($1.63 billion) of U.S. global health assistance for FP/RH, MCH, and PEPFAR. Half of these countries (7) were in Africa, and the other half were in East Asia and the Pacific (3), South and Central Asia (2), Latin American and the Caribbean (1), and the Near East (1). The MCH program reached the largest number (13), followed by FP/RH (10) and PEPFAR (9).

The remaining 34 countries (61% of countries receiving U.S. support) allow for legal abortion beyond one or more of these exceptions. This includes circumstances where abortion is allowed to preserve the physical or mental health of a pregnant person, for social or economic reasons, or because of fetal impairment. These countries accounted for 61% ($2.9 billion) of U.S. global health assistance for FP/RH, MCH, and PEPFAR. Most of these countries (23) were in Africa, and the remainder were in South and Central Asia (5), East Asia and the Pacific (3), Europe and Eurasia (1), Latin America and the Caribbean (1), and the Near East (1). PEPFAR reached the largest number (27), followed by MCH (22) and FP/RH (19).

There are only 8 countries (14% of countries receiving U.S. support) where abortion is not legal under any circumstance. These accounted for 5% ($238 million) of U.S. global health assistance for FP/RH, MCH, and PEPFAR. Several were in Africa (3), while the remainder were in East Asia and the Pacific (2), Latin America and the Caribbean (2), and the Near East (1). The FP/RH program reached the largest number (6), followed by MCH and PEPFAR (4 each).

| Table 1: Number of Countries Receiving Selected FY 2019 Bilateral U.S. Global Health Assistance,by Program Area and Abortion Law Status | ||||

| Program Area | # of Countries Reached | # of Countries Where Abortion Is Legal In Additional Circumstances Beyond Poses Risk to Life or Due to Rape or Incest | # of Countries Where Abortion Is Legal Only One or More of These Circumstances: Poses Risk to Life or Due to Rape or Incest | # of Countries Where Abortion Is Not Legal |

| FP/RH | 35 | 19 | 10 | 6 |

| MCH | 39 | 22 | 13 | 4 |

| HIV (PEPFAR) | 40 | 27 | 9 | 4 |

| NOTES: FP/RH means Family Planning & Reproductive Health. MCH means Maternal & Child Health. PEPFAR is the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Abortion legal in only one or more circumstances refers to circumstances where pregnancy poses a risk to the life of the pregnant person or results from rape or incest. Additional circumstances allowed beyond those might include, for example, to preserve the physical or mental health of a pregnant person or for social or economic reasons. SOURCES: KFF analysis of data from the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard (foreignassistance.gov/), accessed Jan. 2021, and data from World Health Organization (WHO), Global abortion policies database, 2018, https://abortion-policies.srhr.org/, accessed Dec. 13, 2019, and Center for Reproductive Rights, The World’s Abortion Laws Database, http://worldabortionlaws.com/, accessed Aug. 3, 2021. | ||||

Discussion

As members of Congress, advocates, and others continue to debate the future of the Helms Amendment, this analysis finds that the outcome of these discussions stands to significantly affect access to legal abortion in a large number of countries, primarily those in Africa. Indeed, since most countries receiving U.S. global health assistance (86%) allow for abortion in at least one circumstance, including 25% that allow abortion in only one or more exceptional circumstances, repeal of the Helms Amendment would expand the ability of U.S. global health assistance to support legal abortion in many countries; clarifying Helms to allow such support in exceptional circumstances would also expand the ability of U.S. global health assistance to support legal abortion but in more limited circumstances, such as when a pregnancy poses a risk to a pregnant person’s life. Given that the U.S. is the largest global health donor in most countries, whether or not U.S. lawmakers ultimately decide to repeal Helms or modify it to allow for exceptions will likely have an outsized effect on access to legal abortion in low- and middle-income countries.

| Table 2: Countries Receiving Selected Bilateral U.S. Global Health Assistance,by Program Presence and Abortion Law Status, with Total FY 2019 Funding | |||||||

| Region | Country | USG Program Presence | Total FY 2019 Funding Across These Programs*(U.S. $) | ||||

| FP/RH | MCH | HIV (PEPFAR) | # of USG Programs | ||||

| TOTAL NUMBER OF COUNTRIES | 56 | 35 | 39 | 40 | – | $4,770,715,000 | |

| Abortion Legal in Additional Circumstances Beyond Poses Risk to Life or Due to Rape or Incest (34 Countries) | |||||||

| Africa | Angola | X | – | X | 2 | 6,932,000 | |

| Africa | Benin | X | X | – | 2 | 8,000,000 | |

| Africa | Botswana | – | – | X | 1 | 38,667,000 | |

| Africa | Burkina Faso | X | X | X | 3 | 12,023,000 | |

| Africa | Burundi | X | X | X | 3 | 25,310,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Cambodia | X | X | X | 3 | 8,005,000 | |

| Africa | Cameroon | – | – | X | 1 | 139,728,000 | |

| Africa | Central African Republic | – | X | – | 1 | 1,000,000 | |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Colombia | – | X | – | 1 | 3,000,000 | |

| Africa | Democratic Republic of the Congo | X | X | X | 3 | 132,679,000 | |

| Africa | Eswatini | – | – | X | 1 | 69,028,000 | |

| Africa | Ethiopia | X | X | X | 3 | 145,119,000 | |

| Africa | Ghana | X | X | X | 3 | 30,076,000 | |

| Africa | Guinea | X | X | – | 2 | 8,000,000 | |

| South/Central Asia | India | X | X | X | 3 | 23,491,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Indonesia | – | X | X | 2 | 19,596,000 | |

| Near East | Jordan | X | – | – | 1 | 21,000,000 | |

| Africa | Kenya | X | X | X | 3 | 276,972,000 | |

| South/Central Asia | Kyrgyzstan | – | – | X | 1 | 6,279,000 | |

| Africa | Lesotho | – | – | X | 1 | 84,617,000 | |

| Africa | Liberia | X | X | X | 3 | 19,500,000 | |

| Africa | Mozambique | X | X | X | 3 | 314,904,000 | |

| Africa | Namibia | – | – | X | 1 | 69,135,000 | |

| South/Central Asia | Nepal | X | X | X | 3 | 40,427,000 | |

| Africa | Niger | X | X | – | 2 | 16,119,000 | |

| South/Central Asia | Pakistan | – | X | – | 1 | 3,000,000 | |

| Africa | Rwanda | X | X | X | 3 | 80,861,000 | |

| Africa | South Africa | – | – | X | 1 | 718,285,000 | |

| South/Central Asia | Tajikistan | – | X | X | 2 | 7,731,000 | |

| Africa | Togo | – | – | X | 1 | 1,632,000 | |

| Europe/Eurasia | Ukraine | – | – | X | 1 | 27,200,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Vietnam | – | – | X | 1 | 27,084,000 | |

| Africa | Zambia | X | X | X | 3 | 371,446,000 | |

| Africa | Zimbabwe | X | X | X | 3 | 147,094,000 | |

| Abortion Legal in Only One or More of These Circumstances: Poses Risk to Life or Due to Rape or Incest (14 Countries) | |||||||

| South/Central Asia | Afghanistan | X | X | – | 2 | 31,468,000 | |

| South/Central Asia | Bangladesh | X | X | – | 2 | 48,123,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Burma | – | X | X | 2 | 18,450,000 | |

| Africa | Côte d’Ivoire | X | X | X | 3 | 55,629,000 | |

| Africa | Malawi | X | X | X | 3 | 170,935,000 | |

| Africa | Mali | X | X | X | 3 | 36,300,000 | |

| Africa | Nigeria | X | X | X | 3 | 486,417,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Papua New Guinea | – | – | X | 1 | 4,901,000 | |

| Africa | South Sudan | X | X | X | 3 | 59,536,000 | |

| Africa | Tanzania | X | X | X | 3 | 325,338,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Timor-Leste | X | X | – | 2 | 2,000,000 | |

| Africa | Uganda | X | X | X | 3 | 381,320,000 | |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Venezuela | – | X | – | 1 | 5,000,000 | |

| Near East | Yemen | – | X | – | 1 | 3,500,000 | |

| Abortion Not Legal (8 Countries) | |||||||

| Latin America/Caribbean | Dominican Republic | – | – | X | 1 | 26,482,000 | |

| Near East | Egypt | X | – | – | 1 | 10,000,000 | |

| Latin America/Caribbean | Haiti | X | X | X | 3 | 125,011,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Laos | – | – | X | 1 | 780,000 | |

| Africa | Madagascar | X | X | – | 2 | 28,200,000 | |

| East Asia/Pacific | Philippines | X | – | – | 1 | 13,000,000 | |

| Africa | Senegal | X | X | X | 3 | 30,385,000 | |

| Africa | Sierra Leone | X | X | – | 2 | 4,000,000 | |

| NOTES: FP/RH means Family Planning & Reproductive Health. MCH means Maternal & Child Health. PEPFAR is the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. Abortion legal in only one or more circumstances refers to circumstances where pregnancy poses a risk to the life of the pregnant person or results from rape or incest. Additional circumstances allowed beyond those might include, for example, to preserve the physical or mental health of a pregnant person or for social or economic reasons. X indicates country receiving bilateral assistance through USAID and the Department of State in FY 2019. * indicates total does not include funding for regional or “worldwide” program efforts that may reach additional countries not reflected in this table. “–” indicates country-level funding is not available on ForeignAssistance.gov. SOURCES: KFF analysis of data from the U.S. Foreign Assistance Dashboard (foreignassistance.gov/), accessed Jan. 2021, and data from World Health Organization (WHO), Global abortion policies database, 2018, https://abortion-policies.srhr.org/, accessed Dec. 13, 2019, and Center for Reproductive Rights, The World’s Abortion Laws Database, http://worldabortionlaws.com/, accessed Aug. 3, 2021. | |||||||

- See: U.S. Congress, Department of State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs Appropriations Act, 2022 (H.R. 4373), 117th Congress. ↩︎

- The Abortion is Healthcare Everywhere Act would amend the Foreign Assistance Act to remove this language from permanent law. On the other hand, the American Values Act would restate the Helms Amendment as included in the amended Foreign Assistance Act of 1961. See: U.S. Congress, Abortion is Health Care Everywhere Act of 2021 (H.R. 1670), 117th Congress; U.S. Congress, S.239 – American Values Act (S. 239), 117th Congress. ↩︎

- President Biden supports repeal of the Hyde amendment and did not include it in its budget request to Congress. See: Colby Itkowitz, “Biden budget plan removes decades-old ban on federal funds for abortions,” Washington Post, May 28, 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/biden-budget-abortion-hyde-amendment/2021/05/28/7b248838-bfde-11eb-b26e-53663e6be6ff_story.html. ↩︎

- In all instances, the U.S. continues to provide U.S. funding to support post-abortion care (PAC). See: USAID, “Memo from Duff Gillespie on Post-Abortion Care,” Sept. 10, 2001, https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/documents/1864/duff_memo.pdf. ↩︎

- USAID, Guidance on the Definition and Use of the Global Health Programs Account: A Mandatory Reference for ADS Chapter 201, partial revision as of Dec. 12, 2014, https://www.usaid.gov/ads/policy/200/201mau. ↩︎