VOLUME 26

States Expand Access to Ivermectin as Cancer Myths Continue, and Abortion Pill Faces False Water Supply Claim

Summary

This volume examines how unsupported claims about ivermectin as a cancer treatment have coincided with legislative efforts to expand access to the drug. It also explores the promotion of unproven “detox” supplements in response to falsehoods about the spike protein from the COVID-19 virus and vaccine, along with the unsubstantiated claim that byproducts from medication abortion pills contaminate the water supply. Lastly, it analyzes the renewed debate over ADHD diagnoses and treatments, including how stigma and shifting policy may affect treatment access.

Recent Developments

State Policy Changes Follow Ongoing Promotion of Ivermectin as Cancer Treatment

Persistent unsupported claims about ivermectin’s effectiveness in treating a range of diseases, including cancer and COVID-19, have coincided with state-level policy efforts to make the drug more accessible. While some studies have suggested ivermectin may enhance the efficacy of chemotherapy and immunotherapy drugs, its use for cancer treatment has not been extensively studied in humans and it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this purpose. Oral ivermectin is currently FDA-approved to treat certain parasitic infections in humans, like strongyloidiasis and onchocerciasis, and topical forms are approved to treat head lice and rosacea. Some social media users, though, continue to promote it as a cancer treatment, often sharing personal testimonials that frame the drug as a “miracle cure.” KFF’s monitoring of social media found that the share of cancer-related posts mentioning ivermectin doubled, albeit from a small share to start, in the first half of 2025 compared to all of 2024, with such posts accounting for more than 4% of all cancer-related content identified in our search this year. Between May 28 and June 26, some of the most-engaged-with posts relating to ivermectin as a cancer treatment came from a medical influencer with more than 565,000 followers on X. Their posts called ivermectin a “cutting-edge” cancer treatment and cited anecdotal stories of alleged success treating cancer with ivermectin and other anti-parasitic drugs.

Sixteen states have introduced or passed bills that would make ivermectin available over-the-counter, although pharmacists have expressed reluctance to dispense it without FDA approval for non-prescription or off-label use. Although some share personal stories of themselves or people they know treating their cancer with ivermectin, no major health organizations or regulatory bodies have approved it for cancer treatment, and the use of ivermectin could pose health risks. According to the FDA, ivermectin can interact with other medications, including blood thinners, and overdoses may lead to seizures, coma, or death. Claims that ivermectin can treat cancer may also lead some patients to pursue alternative treatments or delay effective therapies, both of which may result in higher mortality rates.

Polling Insights: KFF polling from 2023 found that about half (48%) of the public has heard the false claim that ivermectin is an effective treatment for COVID-19. While few adults overall say they think this myth is definitely true (6%), seven in ten express uncertainty, saying it is either “probably true” (26%) or “probably false” (44%).

There are notable partisan differences when it comes to believing or leaning toward believing this false claim. About half (48%) of Republicans say it is either “definitely true” or “probably true” that ivermectin is an effective treatment for COVID-19, compared to about three in ten independents (28%) and one in five Democrats (18%).

Unproven “Detoxes” for Spike Protein from COVID-19 Virus and Vaccine Gain Renewed Attention Online

Mentions of alleged spike protein “detoxes” have increased on social media, fueled by continued falsehoods that the spike protein produced during COVID-19 exposure or vaccination lingers in the body and causes long-term harm. There is no evidence that the spike protein from vaccines is toxic or remains in the body for an extended period, yet “detox” products continue to be marketed online. The largest volume of social media mentions in 2025, as identified in our search of terms related to spike protein “detoxes,” occurred on May 26, following reports of alleged vaccine-related injuries. Mentions rose again in June when a podcast host posted on X promoting a $90 supplement that claims to “break down spike protein and disrupt its function.” In reality, the spike protein produced by an mRNA vaccine only attaches to the outer layer of cells to trigger an immune response against future illness and typically clears from the body after a few days.

A popular “detox” formula, which is marketed by a medical doctor whose credentials were revoked for promoting false claims about COVID-19 vaccines, contains nattokinase, bromelain, and curcumin. These supplements are generally considered safe, but their use as spike protein detoxes lacks scientific support and may carry risks. Nattokinase and bromelain have blood-thinning properties that can interact with anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications, potentially increasing the risk of excessive bleeding. Curcumin may pose similar risks and has been associated with liver injury in some cases. Infectious disease doctors warn that promoting unnecessary and potentially harmful “detox” products may further erode public trust in the safety of COVID-19 vaccines.

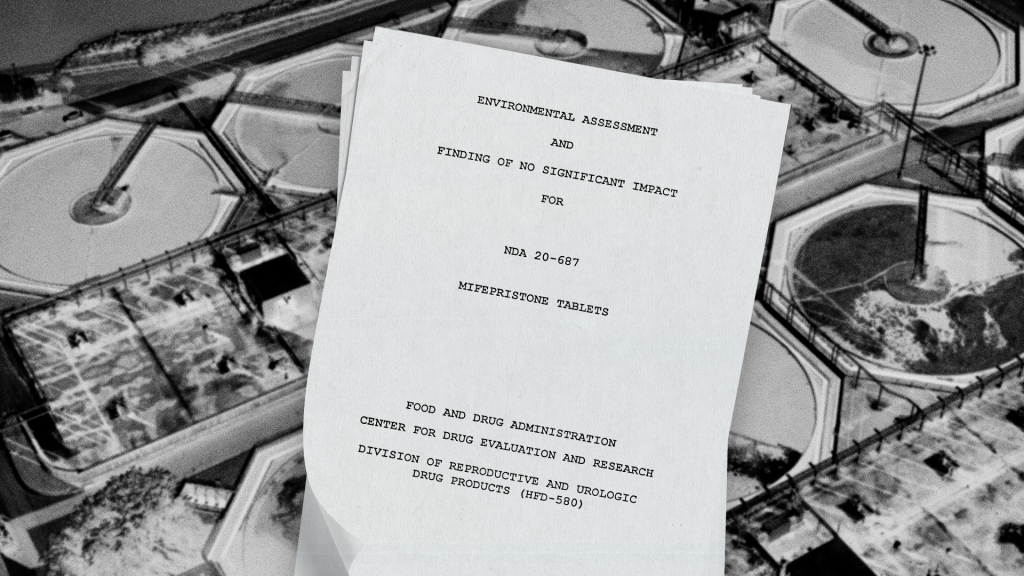

Abortion Opponents Fabricate Concerns About Water Contamination in Effort to Restrict Access to Abortion Pills

The baseless narrative that medication abortion pills, particularly mifepristone, contaminate the water supply through urine and menstrual blood is circulating online alongside unfounded claims that abortion pill byproduct in water systems can lead to negative impacts on fertility, public health, and the environment. Federal agencies and independent researchers have found no evidence that mifepristone contaminates the water supply at levels that cause harm, but unsupported claims have appeared sporadically over the past few years, recently gaining traction in late June.

On June 17, a report from an advocacy group that opposes abortion access alleged that over 40 tons of fetal remains and abortion pill byproducts have entered the water system, potentially causing infertility and other reproductive health problems. The report did not include any evidence to substantiate the allegation. While the report was not covered by major news outlets, it circulated widely through non-mainstream news, anti-abortion advocacy groups, and policymakers who called for federal agencies to test the water supply for abortion pill byproducts. The following day, twenty-five House and Senate Republicans signed a letter to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) calling for an investigation into the matter. Later, a video clip circulated widely online of a U.S. congresswoman who opposes abortion stating, without evidence, that the water supply is “severely contaminated” by abortion drugs. Social media users who shared the clip amplified the claim, including one X user with more than 259,000 followers. Others questioned the legitimacy of the claim by noting that the FDA and environmental scientists have found no basis for this claim.

An environmental assessment conducted as a part of the FDA’s approval process for the drug estimated its environmental concentration to be less than one part per billion – an amount considered too low to affect standard test organisms. The FDA has described that estimate as conservative because it does not account for metabolism of the drug by the human body or the ability of wastewater treatment plants to remove pharmaceuticals from water. Despite a lack of evidence of harm, state lawmakers in Wyoming and Texas introduced bills earlier this year aiming to mandate testing of water supplies for excreted fetal tissue and abortion medication byproduct. As access to mifepristone remains at risk, these narratives and legislative efforts may contribute to further restrictions on abortion access through arguments not grounded in science and unrelated to medical safety or reproductive rights. Additionally, elevating these unproven claims to call for a federal investigation, despite the lack of scientific basis, could further erode trust in public health institutions and regulatory bodies.

Debate Over ADHD Medication Resurfaces on Social Media

Concerns about the overmedicalization of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have existed for decades, with the scientific community divided over how often the condition is overdiagnosed or overtreated. The ongoing debate coincides with rising diagnoses, although nearly one-third of those diagnosed receive no treatment. A 2021 scoping review found evidence of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, particularly among youth with mild symptoms, but other literature attributes rising diagnoses to shifting diagnostic criteria, greater public awareness, and historic disparities in underrepresented populations.

The long-running public debate was renewed by the resurfacing of a 2005 interview with actor Tom Cruise, who criticized the legitimacy of psychiatric diagnoses and pharmaceutical treatments. The video, reposted in late May, became the most shared post on X identified through our search of terms related to ADHD medications between May 27 and June 25. Some users praised Cruise’s skepticism and repeated claims that pharmaceutical companies have over-influenced mental health care. Others repeated stigmatizing claims about ADHD medication, including linking it to violence, despite multiple studies showing that ADHD medications reduce the risk of criminality, self-harm, and other adverse outcomes. These narratives may contribute to stigma around ADHD and its treatment, potentially dissuading individuals or parents from seeking or continuing treatment. Claims of overmedicalization have also influenced recent policy discussions. A May report from the White House’s Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Commission identified overmedicalization as a key factor in childhood chronic disease. The report further claimed that there is evidence that ADHD medications do not improve long-term outcomes, but ADHD specialists and advocacy groups have argued that the research cited is flawed and does not account for changes in medication practices. Proposed changes by the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to its telemedicine rules have also raised concern about access to ADHD medication. The agency said it received 38,000 comments on its proposed rules, many of which expressed concern that the changes might limit availability. Nearly half of adults with ADHD reported having used telehealth to receive treatment.

AI & Emerging Technology

Study Finds Small Language Changes Can Alter AI Medical Advice

As medical providers seek to incorporate artificial intelligence (AI) tools in clinical environments, new research from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) finds that large language models (LLMs) may generate inconsistent medical advice to users based on small changes to patient messages, like including typos, extra white spaces, or colloquial language. Researchers tested four commonly used LLMs by introducing minor, non-clinical language changes designed to simulate messages that might be written by different patient populations seeking advice from these models. This included people with limited English proficiency or health anxiety.

Across all of the altered messages, LLMs were 7-9% more likely to recommend self-management solutions rather than seeking medical care. The study compared these recommendations to those of clinicians and found that in many cases, the AI suggested self-management when providers would recommend escalating medical care. The effect was amplified for women, with researchers noting that the models made about 7% more errors for female patients and were more likely to recommend self-management. Researchers cautioned that the models’ sensitivity to irrelevant linguistic cues, particularly those designed to mimic vulnerable populations, could lead to uneven care recommendations and reinforce health disparities.

Support for the Health Information and Trust initiative is provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of RWJF and KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities. The data shared in the Monitor is sourced through media monitoring research conducted by KFF.