How Does Gaining Coverage Affect People's Lives? Access, Utilization, and Financial Security among Newly Insured Adults

Who gained coverage in 2014?

In some ways, the low- and middle- income “newly insured” population (those who gained coverage in 2014 and were uninsured before gaining that coverage) and “uninsured” population (those who lacked coverage in fall 2014) resemble each other. For example, they are similar with respect to income, work status, age, and family type, and they differ from the low- and middle-income “previously insured” population (people who had coverage before 2014 and still had it in 2014) on these factors. However, the newly insured population differs from their counterparts who remained without coverage on some important factors, such as race/ethnicity, gender, and immigration status. These differences in part reflect ongoing barriers to coverage among some groups and in part reflect higher take-up among others.

Even within the low- and middle-income population, newly insured adults are more likely to be lower-income than previously insured adults. More than half (56%) of adults in the income range for ACA financial assistance are in families at or below 138% of poverty, a rate that is not statistically significantly different from the remaining uninsured. In contrast, previously insured adults in the low- and middle-income range are more likely to fall into the middle-income range, with 63% having family incomes between 139 and 400% of poverty (Figure 3). The fact that newly insured adults are more likely to be in the lowest income group may have implications for their financial stability and ability to navigate the health system, as lower-income individuals face more barriers to health care than higher-income people.

Figure 3: Income Distribution Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, By Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

Not surprisingly, adults who are newly insured through Medicaid are significantly more likely to be in the lowest income group than adults who gained Marketplace or other private coverage, who are more likely to be middle-income (data not shown). Medicaid eligibility is targeted to adults with the lowest incomes, with the ACA extending eligibility to most adults with incomes at or below 138% in states that expanded. Some adults, such as pregnant women or working adults with disabilities, may qualify for Medicaid at higher incomes through pathways in place before the ACA.

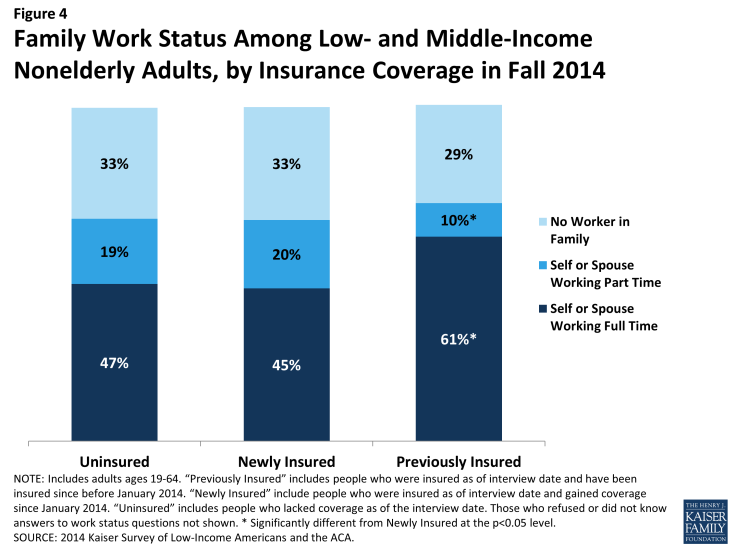

Newly insured adults are more likely to be in a family working part-time (versus full-time) than their previously insured counterparts. A majority of low- and middle-income adults who gained coverage in 2014 live in a family with a worker, meaning either they or their spouse works full time (45%) or part time (20%), and a third (33%) are in a family with no worker (Figure 4). This distribution is not significantly different from the uninsured. However, previously insured adults are more likely than newly insured adults to have a full-time worker in the family and less likely to have a part-time worker. This pattern reflects the historical ties between work and health insurance, since most people who had coverage before the ACA obtained that coverage through a job and people without full-time employment had limited access to affordable coverage. With new coverage provisions in place as of 2014, there were more options for health insurance outside employment, particularly for people in states that expanded Medicaid.

Figure 4: Family Work Status Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

Within the newly insured population, those newly insured through Medicaid were less likely than adults with other coverage (including Marketplace) to be in a full-time working family (data not shown). This finding is not surprising given that Medicaid eligibility targets those in the lowest income bracket, and people with lower incomes are less likely to work full-time. However, compared to adults who had Medicaid coverage before 2014, those who gained Medicaid coverage were more likely to be in a family with a worker. With the expansion of Medicaid in many states, eligibility levels were raised to levels where one could work part-time and still meet income limits.

Half of newly insured adults are under age 35. Despite concerns that many people who sign up for coverage would be older adults who were more at risk for health problems, half of newly insured adults were under age 35 (Appendix Table 1). Nearly a fifth (19%) were aged 19 to 25, the so-called “young invincible” group. The age distribution of the newly insured was similar to the remaining uninsured population but younger than the previously insured population. These differences likely reflect the fact that those who lacked coverage prior to 2014 were more likely to be young, since younger adults have looser ties to employment and lower incomes. Within the newly insured population, there were no significant differences in age distribution between Medicaid and Marketplace enrollees, though newly insured adults with employer coverage were less likely than those who gained ACA coverage to be age 45-64.

The newly insured population is more likely to be female than their counterparts who remained without coverage. Nearly six in ten (58%) of the newly insured population is female, a share significantly higher than that among the remaining uninsured (45%) but not significantly different from the previously insured (Appendix Table 1). Women have historically had a lower uninsured rate than men,1 and the gender patterns in who gained coverage may reflect women taking up coverage at a higher rate than men. There were no significant differences in gender by coverage type within the newly insured population.

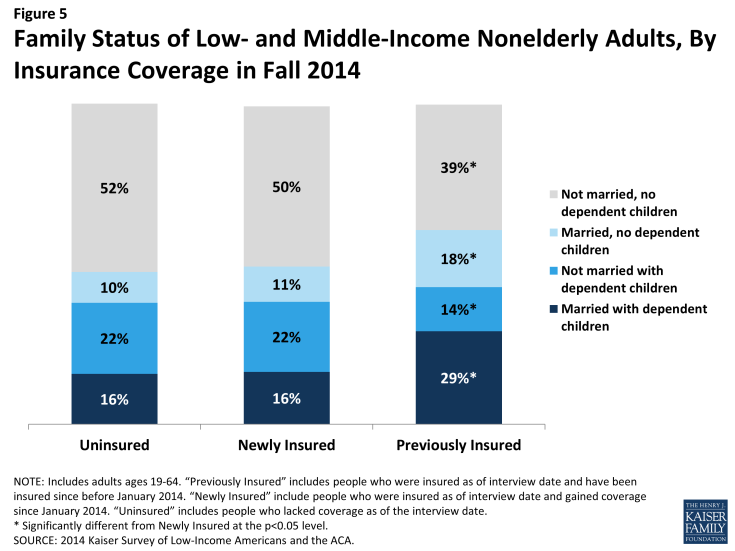

More than half of newly insured adults are adults without dependent children, a group that has generally been excluded from publicly-financed health coverage in the past. About six in ten (61%) newly insured adults do not have dependent children, and 72% are not married (Figure 5). These shares are similar to those among the remaining uninsured population. In the past, non-elderly adults without dependent children could only qualify for Medicaid if they were disabled or pregnant, and private coverage as an adult dependent was generally restricted to spouses. With new coverage expansions, some people who faced limits to accessing coverage due to family structure were able to gain coverage. Previously insured adults were most likely to be married, perhaps reflecting the availability of family coverage in the private market. Within the newly insured population, there were no significant differences by coverage in the share of adults who were not married without dependent children.

Figure 5: Family Status of Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, By Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

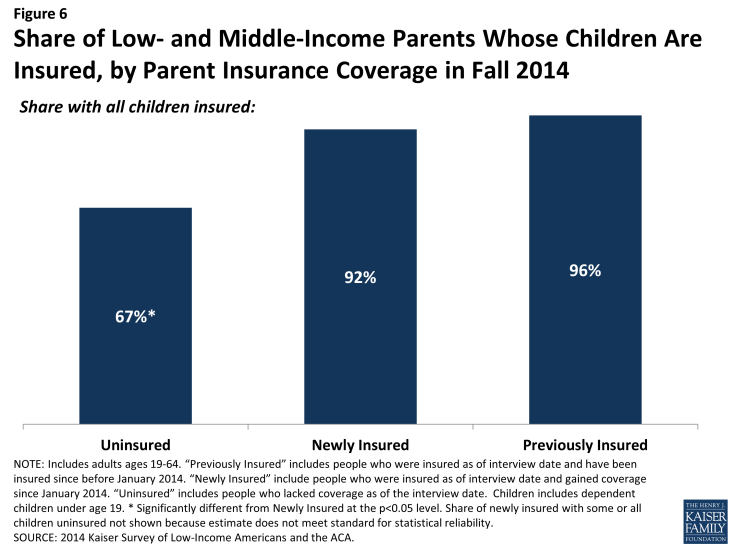

Among parents, newly insured adults were less likely to have uninsured children than adults who remained without coverage. The vast majority of uninsured children are eligible for coverage under the ACA: Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) are available to most children in low-income families, and children may be covered along with their parents in Marketplace coverage. Research has found that parent coverage in public programs is associated with higher enrollment of eligible children.2 Coverage patterns in 2014 support this finding: newly insured parents were less likely than uninsured parents to have uninsured children, and nearly all newly insured and previously insured parents had all of their children insured (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Share of Low- and Middle-Income Parents Whose Children Are Insured, by Parent Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

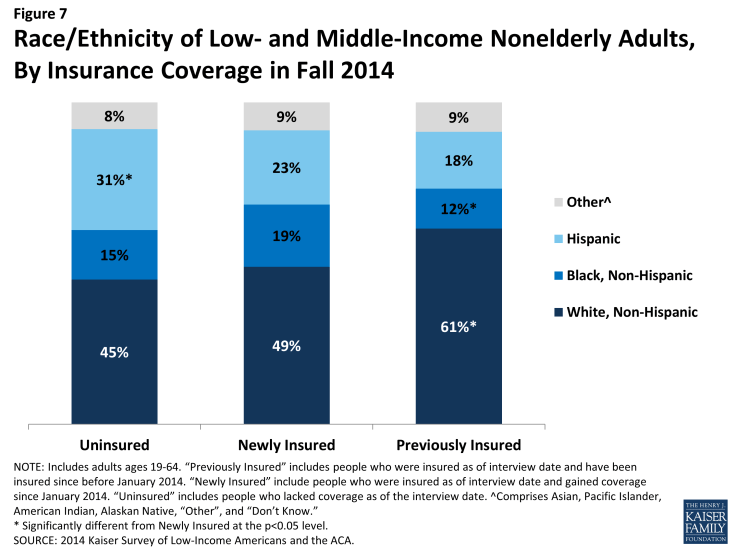

Over half of newly insured adults are people of color. Reflecting historical patterns of the uninsured being more likely to be people of color than the insured, the newly insured are less likely than the previously insured to be White, Non-Hispanic, though they are no more or less likely to be White, Non-Hispanic than adults who remained uninsured (Figure 7). Notably, the newly insured population is less likely to be Hispanic than the remaining uninsured. This pattern likely reflects a combination of factors, including language barriers, immigration policy, and work status, that led to the remaining uninsured being disproportionately Hispanic. There were no significant differences in race/ethnicity of the newly insured population by type of coverage gained.

Figure 7: Race/Ethnicity of Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, By Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

The vast majority of newly insured adults are U.S. citizens. Nearly nine in ten (87%) of newly insured adults are citizens, and 7% are legal immigrants (Appendix Table 1). The remainder is immigrants who are in the United States without a green card. While federal law bars undocumented immigrants from ACA coverage either through Medicaid or the Marketplace, as documented elsewhere, immigrants without green cards may acquire coverage through a job, directly from insurers outside the Marketplace, or through state-only programs.3,4,5 However, bans on coverage among undocumented immigrants are evident in the higher share (15%) of remaining uninsured who fall into this category. Among the previously insured, nearly all (97%) are U.S. citizens or legal immigrants. Within the newly insured population, there were no significant differences in the share of US citizens by type of coverage.

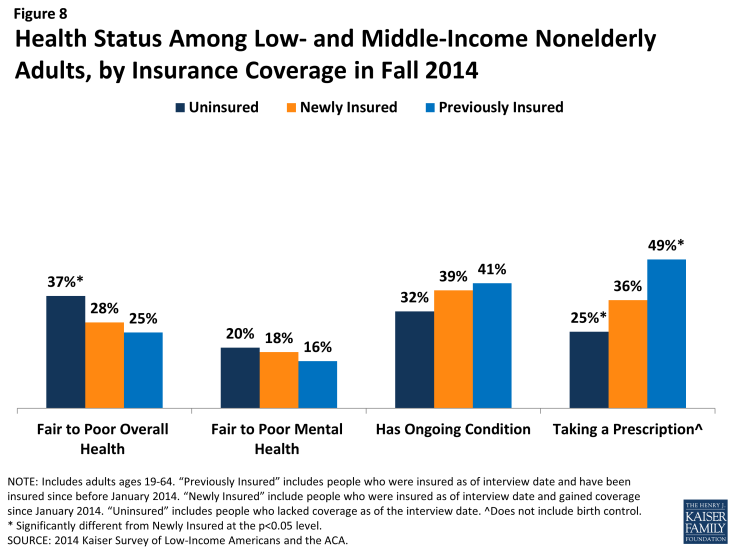

Newly insured adults do not differ significantly from the previously insured on most measures of health status, but they are less likely than their uninsured counterparts to report fair or poor health. Nearly three in ten (28%) newly insured adults rate their overall health as fair or poor, a share that is not significantly different from the previously insured but is lower than the remaining uninsured (Figure 8). Nearly a fifth (18%) reports their mental health is fair or poor and about four in ten (39%) report that they have an ongoing medical condition that requires regular care, rates about equal to adults in other coverage groups. These findings refute the idea that those who gained coverage are more likely than those who did not to be in poor health or feel they need medical services. However, newly insured adults are less likely than the previously insured and more likely than the uninsured to say they take a prescription on a regular basis.

Figure 8: Health Status Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

Within the newly insured group, adults with Medicaid are more likely say they receive care for an ongoing condition than those with Marketplace coverage (data not shown). Further, adults newly insured through Medicaid were more likely to report fair or poor overall or mental health, to have an ongoing condition, or to take a prescription drug than those newly insured through employer coverage. Several pre-ACA Medicaid eligibility pathways specifically target people with health problems, and some gaining coverage may have qualified through these routes. Many adults also enroll in Medicaid after coming in contact with the medical system, which may explain why these adults are more likely than other newly insured to have a chronic condition.

How do newly insured adults access care?

The ultimate goal of expanding health insurance coverage is to help people access the medical services that they need. A large body of literature has documented that people with insurance are more likely to be linked to regular care, are less likely to postpone care when they need it, and have an easier time accessing services. The survey findings reinforce those findings, indicating that adults who gained coverage in 2014 have better access to care than those who remained without coverage. In addition, the survey findings provide insight into patterns of care among the newly insured and remaining insured. While some newly insured adults report changing where they regularly go for care, many say they continue to seek services from community clinics and health centers, which have historically provided care to under-served populations such as the uninsured.

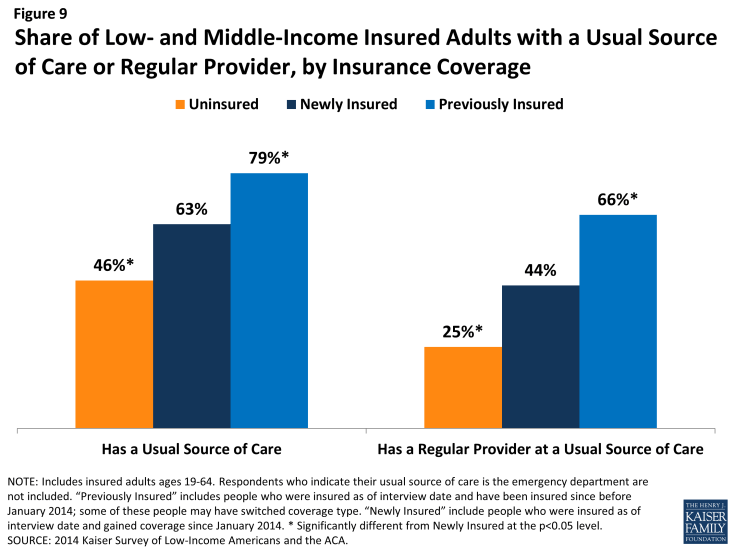

Adults who gained coverage are more likely to be linked to care than those who remained uninsured. Newly insured adults were more likely than those who remained uninsured in Fall 2014 to have a usual source of care, or a place to go when they are sick or need advice about their health (not counting the emergency room); they were also more likely to have a regular doctor at their usual source of care (Figure 9). Having a usual source of care or regular doctor is an indicator of being linked in to the health care system and having regular access to services. These patterns reinforce a large body of research that finds that gaining coverage is associated with improved access to care. However, results also indicate that the newly insured are less likely than the previously insured to have a usual source of care or regular doctor. This finding may indicate that newly insured adults are still navigating the health care system and are not as settled into regular care as their previously insured counterparts. There were no differences in the share with a usual source of care by type of coverage among the newly insured, but adults newly insured through Medicaid were more likely than those newly insured through Marketplace or employer coverage to say they have a regular doctor at their usual source of care.

Figure 9: Share of Low- and Middle-Income Insured Adults with a Usual Source of Care or Regular Provider, by Insurance Coverage

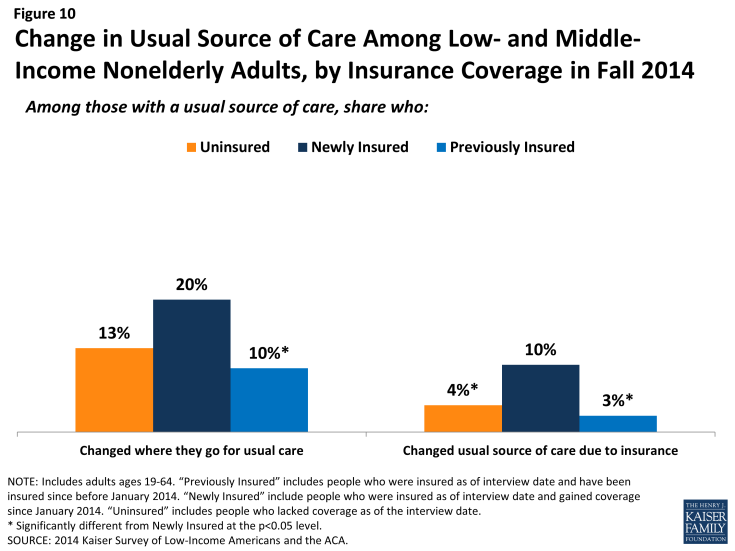

Newly insured adults were more likely to change where they usually go for care than their uninsured or previously insured counterparts. A fifth of newly insured adults who have a usual source of care reported that they changed the place they usually go for care since gaining their coverage (Figure 10). This rate is twice as high as the share of previously insured adults who changed their usual source of care in 2014 (it is also higher than the share of uninsured adults, but the difference is not statistically significant). About half of newly insured adults who changed their site of care reported that it was due to their insurance, a significantly higher rate than the other coverage groups.

Figure 10: Change in Usual Source of Care Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

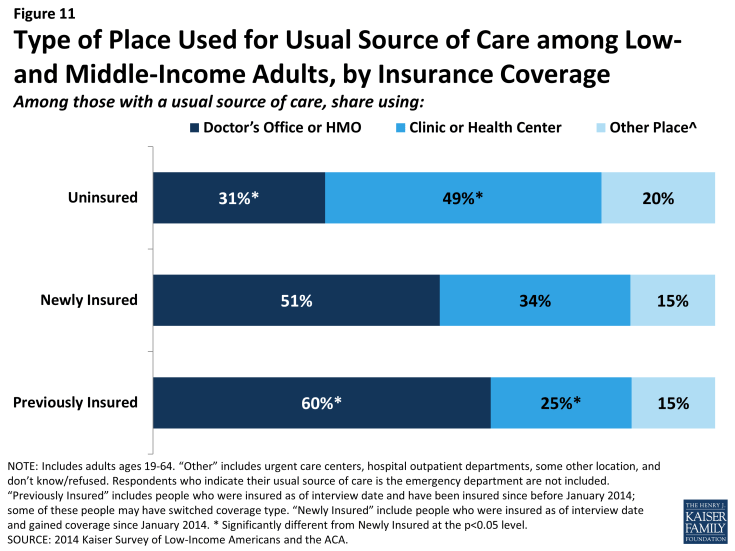

While clinics remain an important source of care for the newly insured, most rely on private doctor’s offices for their regular care. Among newly insured adults who have a usual source of care, about half (51%) say it is a doctor’s office or HMO, and more than a third (34%) say it is a clinic or health center (Figure 11). In contrast, about half of uninsured adults with a usual source of care rely on a clinic or health center, and less than a third use a doctor’s office or HMO for their regular care. Previously insured adults were most likely to use a doctor’s office or HMO and least likely to use clinics as their usual source of care. Historically, clinics and health centers were crucial “safety net” providers for uninsured people. As newly insured gain coverage, many continue to rely on these providers, but they are also more likely to change to a doctor’s office for their care.

Figure 11: Type of Place Used for Usual Source of Care among Low- and Middle-Income Adults, by Insurance Coverage

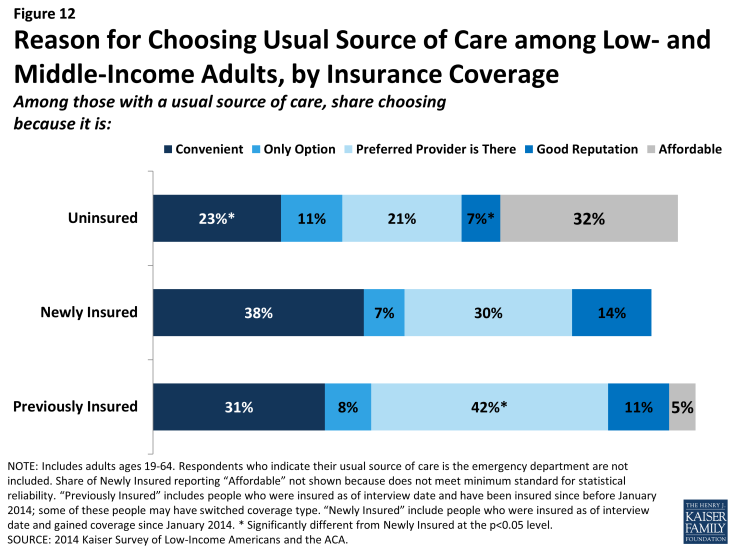

Like their previously insured counterparts, most newly insured adults choose their site of care based on convenience or providers, rather than affordability or lack of options. In the past, many uninsured adults reported that they chose their usual source of care because it was affordable, a pattern that is also seen among adults who were uninsured in 2014. In contrast, adults who gained coverage in 2014 were more likely to say they chose their usual source of care because it was convenient (38%), and many chose it because the provider they prefer to see is there (30%) (Figure 12). They were also more likely than the uninsured to choose their site of care because it has a good reputation. Previously insured adults were more likely than newly insured to choose their usual source of care because their preferred provider is there. These differences may indicate that the previously insured adults have stronger ties to their providers, having been linked to care for a longer period of time.

Figure 12: Reason for Choosing Usual Source of Care among Low- and Middle-Income Adults, by Insurance Coverage

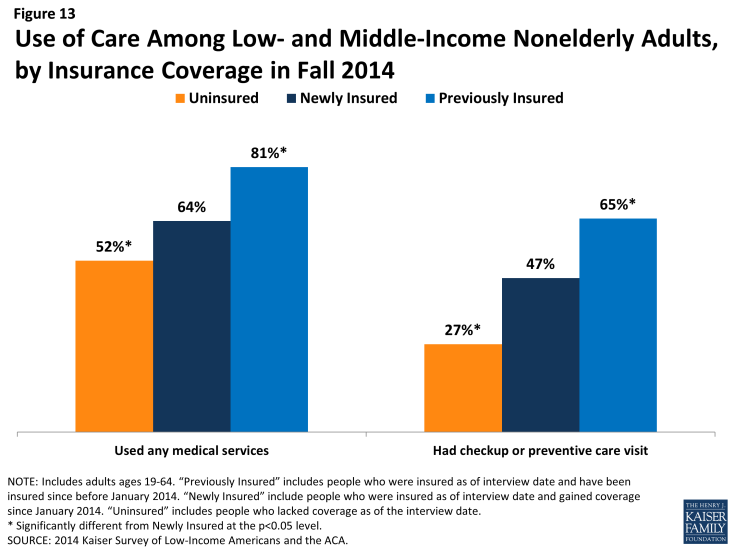

Mirroring patterns of being linked to care, newly insured adults are more likely than their uninsured counterparts to have used medical services or received preventive care. Overall, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults who gained coverage in 2014 said they used at least one medical service since gaining their coverage, and nearly half (47%) had received a preventive visit or check-up (Figure 13). These rates were significantly higher than those for the uninsured in 2014 but were lower than the previously insured reported for 2014. These patterns are not unexpected given the large body of research showing that people with insurance coverage are more likely than those without to use care, including preventive care. The differences between the newly insured and previously insured partially reflect the shorter period of time that the newly insured had their coverage, since most people’s coverage started at least several months into 2014. Analysis of the type of care received (not shown) indicates that differences exist for outpatient services (well-care or sick care) and mental health services but not for hospital-based services, including emergency care, indicating that patterns differ for discretionary versus emergent or high-acuity services. Within the newly insured, adults with employer coverage were less likely than those with Medicaid to have used medical services since gaining coverage, and they were less likely than either Medicaid or Marketplace enrollees to have received a preventive visit since gaining coverage.

Figure 13: Use of Care Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

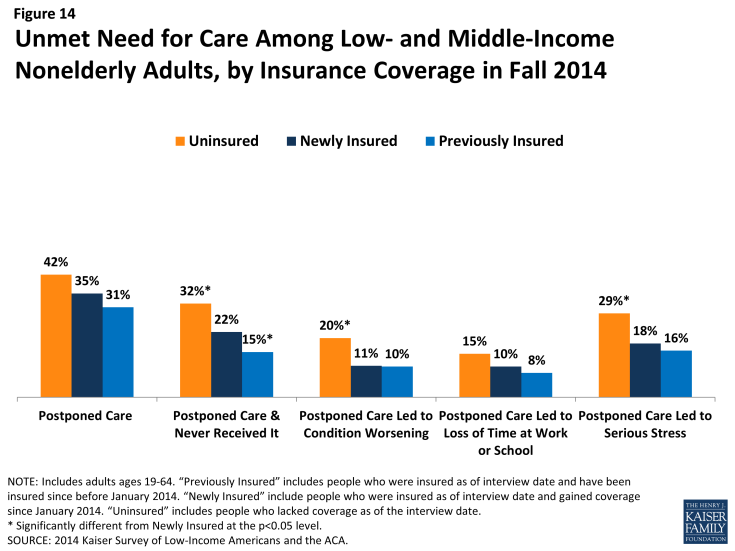

Newly insured adults were less likely than uninsured adults to never receive needed care or face serious consequences of postponing care. While there were no significant differences between coverage groups in the share who postponed care, newly insured adults were significantly less likely than uninsured adults to say they never got the care they needed (22% versus 32%) (Figure 14). They were also less likely to report that postponing care led to a condition worsening or serious stress (there was no significant difference in the share who said postponing care led to time away from work or school). Still, the newly insured were more likely than the previously insured to report problems postponing and never receiving needed care, reflecting some unmet need among those who gained coverage in 2014.

Figure 14: Unmet Need for Care Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

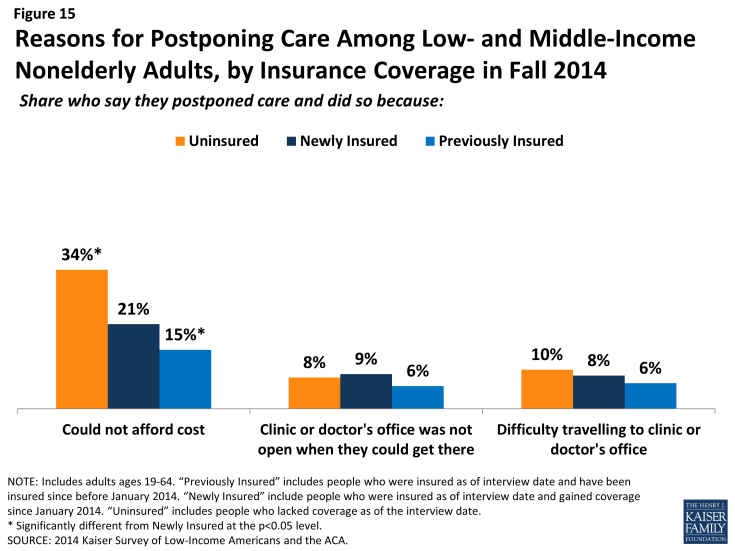

Unmet need could be related to several factors, including difficulty finding a provider, problems navigating the health system and health insurance networks, misunderstanding about how to use coverage and when to seek care, or concerns about out-of-pocket costs. When asked why they postponed care, newly insured adults were less likely than uninsured adults to say cost was a factor (21% versus 34%), but they were more likely than previously insured adults (15%) to say cost was a factor (Figure 15). While Medicaid enrollees pay no or nominal cost-sharing, adults with Marketplace coverage may face out-of-pocket costs, particularly if they do not choose a silver plan (cost sharing subsidies for people with incomes below 250% of poverty are only available if they choose a silver plan).6 In addition, as discussed earlier in this brief, newly insured adults have lower incomes than previously insured adults, which means cost-sharing may pose a bigger burden for them. When asked whether being able to get to the provider when it was open or difficulty traveling to the provider were factors, there were no significant differences in the shares of uninsured, newly insured, and previously uninsured adults who said these things caused them to postpone care.

Figure 15: Reasons for Postponing Care Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

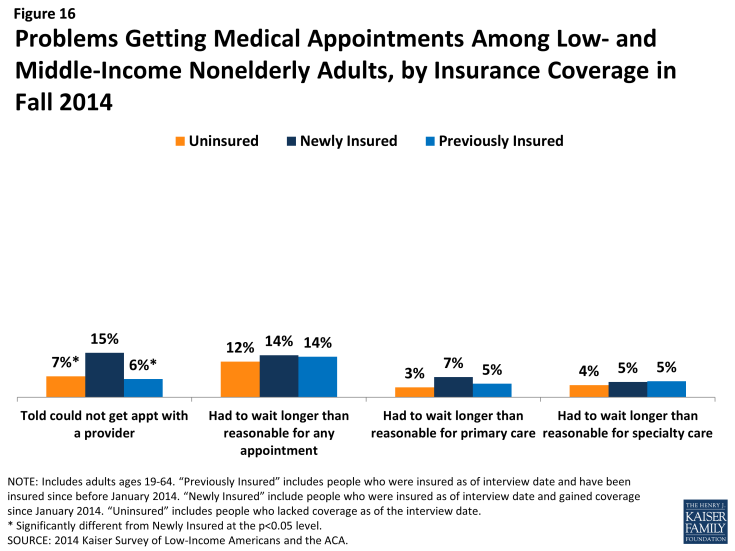

Though most adults did not report problems getting medical appointments, newly insured adults were more likely than other adults to say a provider would not take them as a new patient. Compared to 7% of uninsured and 6% of previously insured adults, 15% of newly insured adults say that a provider told them he/she would not take them as a new patient (Figure 16). Most newly insured adults who reported this problem said it was because the provider did not take their coverage, a rate higher than that for the previously insured. The lower rates among the uninsured likely reflect this group’s lower propensity to seek care, as detailed elsewhere. The higher rates among the newly insured may reflect problems with network adequacy, outdated or inaccurate plan information, or disruptions in care patterns that led newly insured adults to be more likely to seek a new provider.

Figure 16: Problems Getting Medical Appointments Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

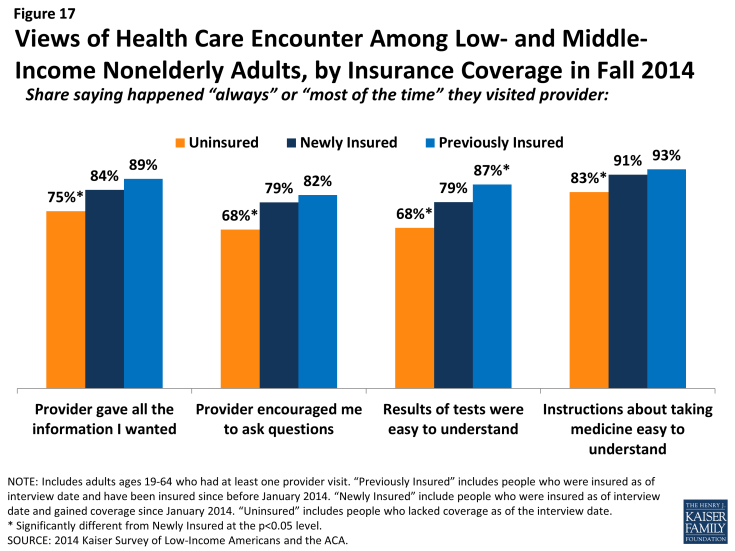

Among adults who received care, newly insured adults were more likely than uninsured to report effective communication with their providers about their care. Once people get into care, health literacy—or “patients’ ability to obtain, process, and understand the basic health information and services they need to make appropriate health decisions”7—plays an important role in how that care affects health outcomes. Health literacy depends on a range of factors related to patients (e.g., engagement in care), providers (e.g., how the information is communicated), service setting (e.g., the length of time of the interaction), and the nature of the visit (e.g., the complexity of health information). In general, it appears that adults with coverage are more likely than those without coverage to report effective communication with their provider, a finding that may be linked to having a regular doctor. Adults who were newly insured were significantly more likely than their uninsured counterparts to report effective communication, including getting all the information they wanted from the provider; feeling encouraged to ask questions; understanding their test results; and understanding how to take their medication (Figure 17). Within the group of newly insured adults, there were no significant differences by coverage type. Further, the only outcome for which there was a significant difference between the newly and previously insured was understanding test results.

Figure 17: Views of Health Care Encounter Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

How does coverage affect financial security?

Health care costs can be a major burden for low-income families. While many newly insured adults report difficulty affording their monthly premium, they also report lower rates of problems with medical bills and lower rates of worry about future medical bills than their uninsured counterparts. However, newly insured adults still face financial insecurity: they are more likely than those who had coverage before 2014 to worry about future medical bills, and they face general financial insecurity at rates similar to the uninsured. These patterns may indicate that while coverage can ameliorate some of the financial challenges that low- and moderate- income adults face, many will continue to face financial challenges in other areas of their lives.

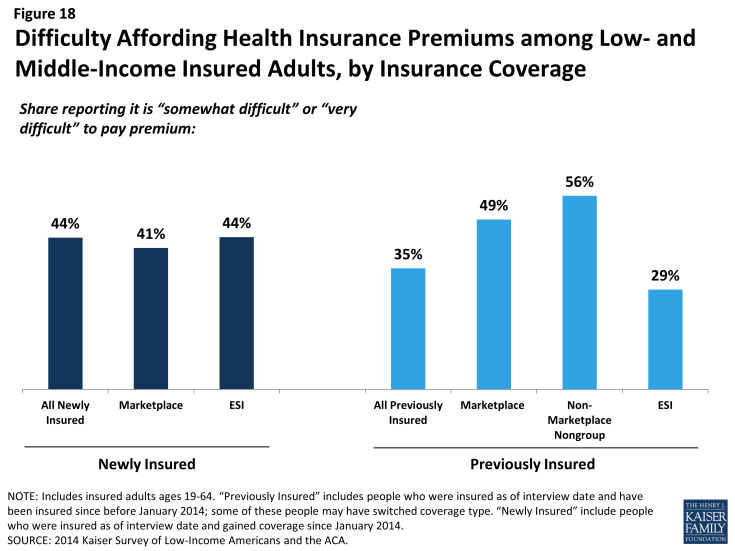

Many low- and middle-income insured adults report difficulty paying their monthly premium. Among adults who say that they pay a monthly premium for their health coverage, more than four in ten newly insured adults (44%) and over a third of previously insured adults (35%) say it is somewhat or very difficult to afford this cost (Figure 18). While rates of difficulty varied by type of coverage among the newly insured, these differences by type of coverage were not statistically significant. Notably, though a majority (85%) of Marketplace enrollees receive premium subsidies,8 many (41% of the newly insured and 49% of the previously insured) still report difficulty affording their premium cost.

Figure 18: Difficulty Affording Health Insurance Premiums among Low- and Middle-Income Insured Adults, by Insurance Coverage

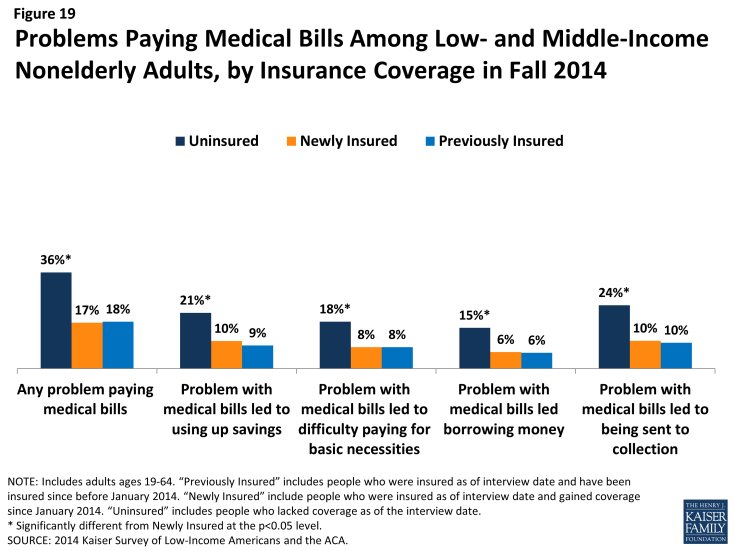

However, coverage does provide financial protection from medical bills and eases concern over affording medical care. Compared to the uninsured, both newly insured and previously insured adults report lower rates of difficulty paying medical bills. Despite being less likely to use services, over a third (36%) of uninsured adults report a problem paying medical bills, a rate twice as high as either the newly insured or previously insured (Figure 19). Uninsured adults were also more likely to report serious consequences from medical bills, such as using up their savings, having difficulty paying for necessities, borrowing money, or being sent to collection. On all measures of problems from medical bills, there were no significant differences between the newly and previously insured.

Figure 19: Problems Paying Medical Bills Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

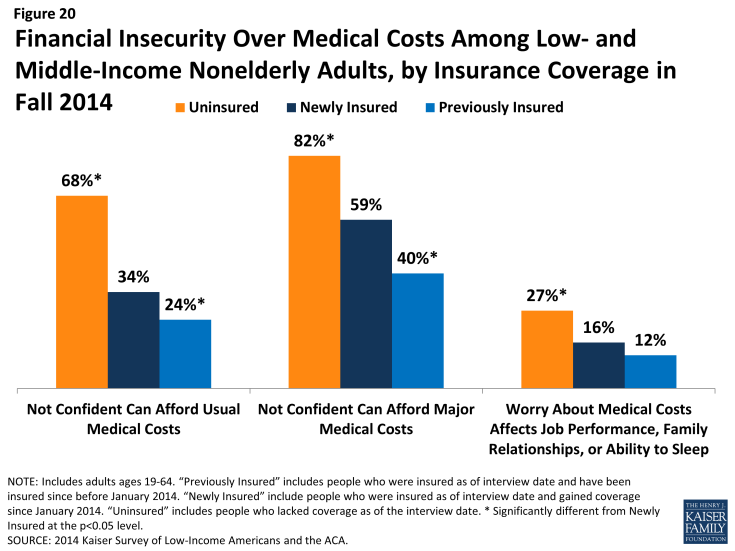

In addition to being less likely to report experiencing financial strain due to medical bills, insured adults are less likely than uninsured to report living with worry about their ability to afford medical care in the future. Newly insured adults were half as likely as uninsured to say they lack confidence in their ability to afford the cost of care for services they typically require (34% versus 68%), and they were also significantly less likely to say they lack confidence in their ability to afford the cost of a major illness (59% versus 82%) (Figure 20). In some cases, this concern has implications for people’s level of stress and affects their daily lives: newly insured adults were less likely than uninsured to say that worry over affording medical costs has affected their job performance, family relationships, or ability to sleep. However, in contrast to reported problems with medical bills, newly insured adults were more likely than previously insured adults to report financial insecurity over future medical bills. Among the newly insured, there were no significant differences in lack of confidence by coverage type. It is possible that newly insured adults have less confidence in the protection offered by their coverage, or it is possible that their recent experience without coverage led them to be more concerned about future coverage and costs.

Figure 20: Financial Insecurity Over Medical Costs Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

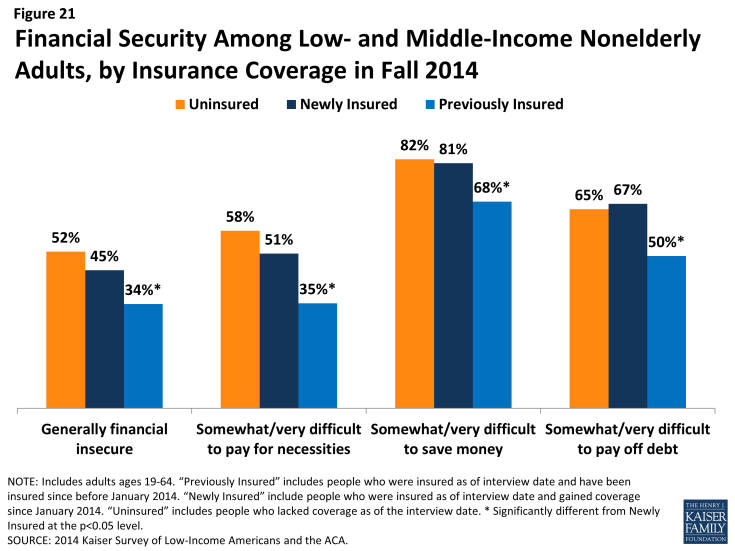

Many newly insured adults still face financial insecurity in areas outside of health care costs. While coverage provides some financial protection from medical bills, newly insured adults are not less likely than uninsured adults to report facing general financial challenges in other areas of their lives. For example, there are no significant differences in the share of uninsured and newly insured adults reporting general financial insecurity or in the share reporting difficulty paying for necessities, saving money, or paying off debt (Figure 21). However, previously insured adults were less likely than newly insured to report these financial challenges.

Figure 21: Financial Security Among Low- and Middle-Income Nonelderly Adults, by Insurance Coverage in Fall 2014

Within the group of newly insured adults, those with Medicaid were more likely than those with other types of coverage to report that they were financially insecure and more likely to say they have difficulty paying for necessities (data not shown). This finding is not surprising, given that Medicaid is targeted to adults with the lowest incomes.

How do the newly insured view their coverage?

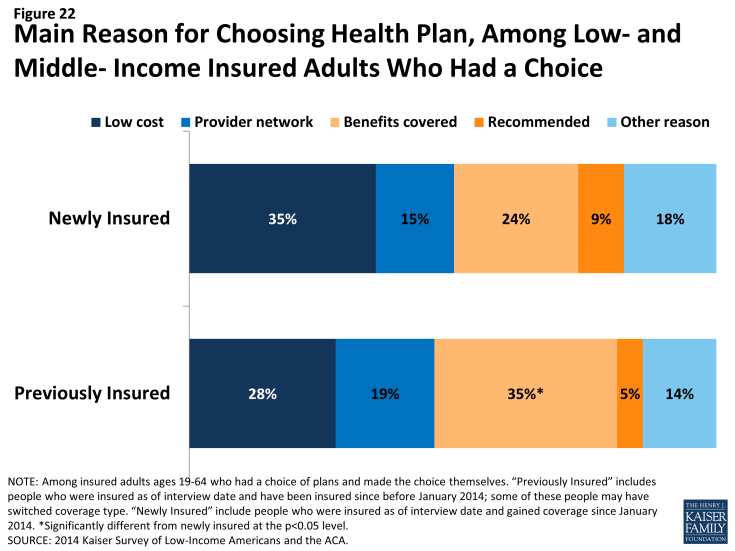

People’s views of their plan may affect not only their use of their coverage but also the likelihood that they re-enroll in coverage or change plans. Survey results reveal that newly insured adults were very sensitive to cost in choosing their plan, placing a priority on cost over benefits and provider networks. A minority of all insured adults reported problems in using their plan. However, newly insured adults were more likely than previously to say they do not understand the details of their plan and were more likely to give their plan a low rating. These findings indicate that additional education may be needed to help people understand their coverage.

Newly insured adults were less likely to prioritize scope of coverage in choosing their plan than previously insured adults. Among adults who say they had a choice of plans and made the choice themselves, under a quarter (24%) of newly insured adults say they chose their plan because of the benefits covered, compared to 35% of previously insured adults (Figure 22). Newly insured adults were most likely to say they chose their plan because of low cost (35%); while this share was higher than the previously insured (28%), the difference was not statistically significant. Newly insured adults may have been less likely to choose based on benefits because new regulations set a minimum scope of coverage across new plans (so called “essential health benefits”), but “grandfathered” pre-existing plans are not held to the same requirement. Alternatively, newly insured adults may be more sensitive to price than their previously insured counterparts, even with the availability of financial assistance for coverage. Notably, more than half (56%) of newly insured Marketplace enrollees say they chose their plan primarily based on cost (data not shown).

Figure 22: Main Reason for Choosing Health Plan, Among Low- and Middle- Income Insured Adults Who Had a Choice

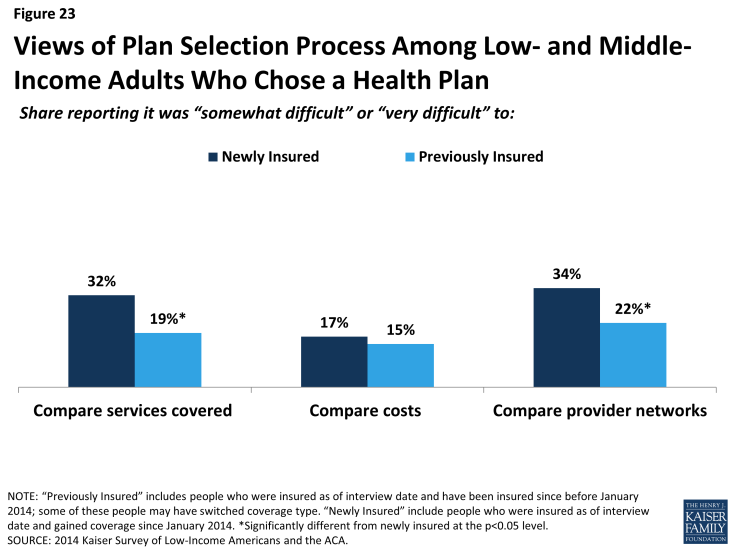

Newly insured adults were more likely to say they had difficulty comparing services and provider networks across plans than previously insured adults. In contrast to comparing costs, which similar shares of the newly insured (17%) and previously insured (15%) said was difficult, newly insured adults who chose a plan were significantly more likely than previously insured to say they found it difficult to compare services (32% versus 19%) or provider networks (34% versus 22%) (Figure 23). Comparing the newly insured and previously insured by coverage type, it appears that these differences may be linked to coverage type. For example, newly insured adults with Marketplace coverage were no more likely to report difficulty than the previously insured with Marketplace coverage (data not shown).

Figure 23: Views of Plan Selection Process Among Low- and Middle-Income Adults Who Chose a Health Plan

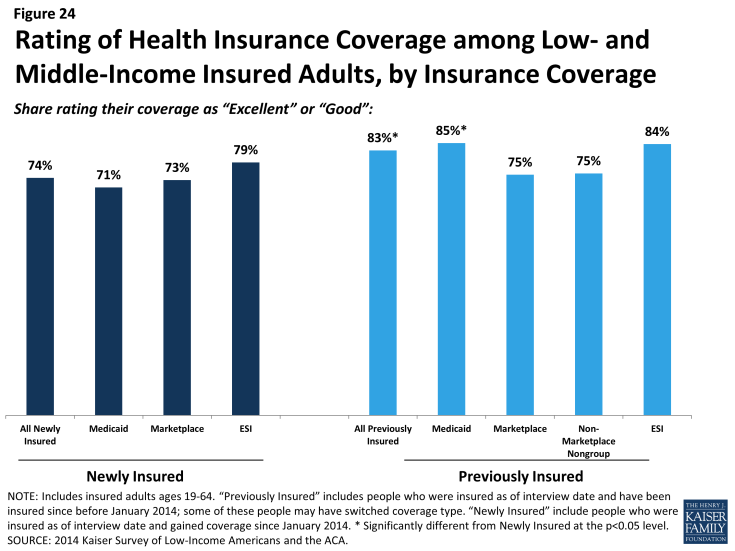

Most newly insured adults give their health plan high ratings, but some report not understanding the details of their plan. Nearly three quarters (74%) of all newly insured adults rate their coverage as “excellent” or “good” (versus “not so good” or “poor”), and this rate did not differ significantly by type of coverage that people gained (Figure 24). While these findings show high rates of satisfaction, adults who had coverage before 2014 were more likely to give their plan a high rating, with 83% saying their coverage was excellent or good.

Figure 24: Rating of Health Insurance Coverage among Low- and Middle-Income Insured Adults, by Insurance Coverage

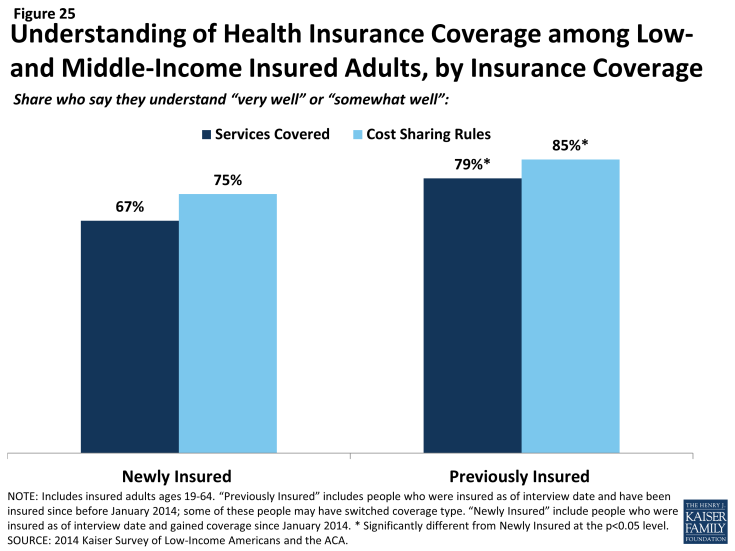

Lower plan ratings among the newly insured could reflect problems with coverage, but, as discussed below, newly insured were no more likely to report problems with their plans than their previously insured counterparts. However, newly insured adults were less likely than previously insured adults to say that they understand their plan (Figure 25). Just two thirds (67%) said they understand the services their plan covers “very well” or “somewhat well” (versus 79% of previously insured adults), and three quarters understand how much they would have to pay when they visit a health care provider (versus 85% of previously insured). These shares were not significantly different across coverage type within the newly insured. It is possible that newly insured adults face challenges in understanding the complexity of insurance coverage, and lower plan ratings could reflect confusion or misunderstanding about coverage.

Figure 25: Understanding of Health Insurance Coverage among Low-and Middle-Income Insured Adults, by Insurance Coverage

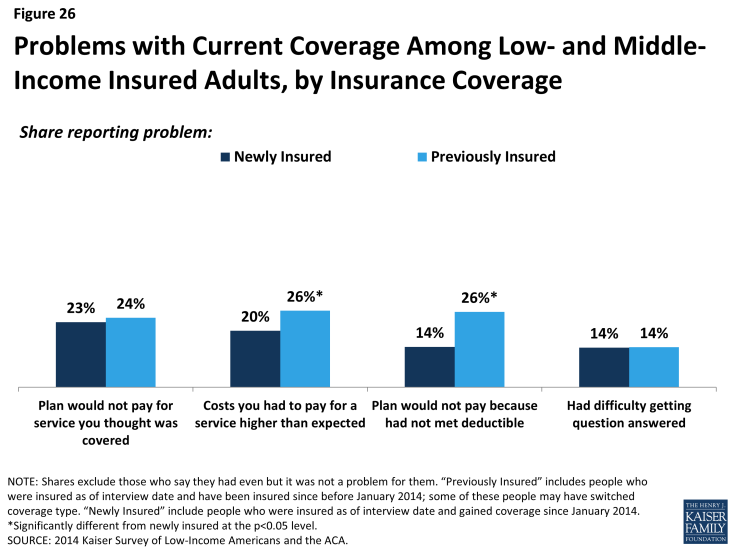

Newly insured adults were no more likely than previously insured to report a specific problem with their health plan. When asked specifically if they encountered various problems with their coverage, such as coverage, costs, or customer service, newly insured adults reported similar or lower rates than previously insured. Specifically, there were no significant differences in shares reporting being denied coverage for a service they thought was covered or having difficulty getting a question answered (Figure 26). Newly insured adults were less likely than previously insured to say they faced higher than expected out-of-pocket costs or that they had not yet met their deductible. Again, within the newly insured group, there were no significant differences in rates of problems by type of coverage, with the one exception of newly insured adults with employer coverage being less likely to say their plan did not cover a service they thought was covered. In addition, there were no consistent patterns in the share of newly insured adults reporting problems by when their coverage started.

Figure 26: Problems with Current Coverage Among Low- and Middle-Income Insured Adults, by Insurance Coverage

Policy Implications

As more and more evidence mounts to document coverage gains during the first year of the ACA, there is interest in understanding how these gains in coverage have affected the lives of the newly insured. Findings from the 2014 Kaiser Survey of Low-Income Americans and the ACA show, not surprisingly, that adults who gained coverage had better access to health care and better financial security from medical costs than those who remained without coverage. Still, comparison to adults who have had coverage since before 2014 show some areas for ongoing attention as policymakers strive to translate coverage to care.

The ACA created new coverage options for people who were left out of coverage in the past. Many people who gained coverage in 2014 were from groups that have historically lagged in access to health insurance, including part-time workers, single adults, and people of color. These groups had high uninsured rates in the past for a variety of reasons, including limited access to coverage through a job, limits on publicly-financed coverage, and low incomes that made affording coverage difficult. With the ACA, some of these barriers to coverage were eased. However, socio-demographic differences between the newly insured and remaining uninsured do reveal some remaining barriers to coverage. For example, the newly insured population is more likely than the remaining uninsured to be female—perhaps indicating a need for more outreach to men—and is more likely to be US citizens or legal immigrants—indicating ongoing restrictions to coverage for some immigrants. Further, while many who gained coverage in 2014 were people of color, indicating advances in addressing longstanding racial and ethnic disparities in health coverage, most of the remaining uninsured are people of color, with more than a quarter identifying as Hispanic. Continued expansion of coverage may be key to further efforts to address ongoing disparities in coverage.

There is limited evidence of selection or a “surge” among newly insured adults. Newly insured adults were no more likely than those who remained without coverage to be older or in poor physical or mental health. In fact, the newly insured adult population reports better health on average than the remaining uninsured population. In addition, compared to those who had coverage since before 2014, there were no differences in self-reported health status, and newly insured adults were less likely to have used medical services. The differences in utilization patterns between the newly insured and previously insured partially reflect the shorter period of time that the newly insured had their coverage, since most people’s coverage started at least several months into 2014. Notably, newly insured adults were no more likely to use emergency care than those who had coverage since before 2014.

Newly insured adults have protection from medical costs but still face some financial difficulty. Compared to their counterparts who remained uninsured, adults who gained coverage in 2014 had better protection from medical bills and less worry about future medical costs. However, newly insured adults still face financial insecurity: they are more likely than those who had coverage before 2014 to worry about future medical bills, and they face general financial insecurity at rates similar to the uninsured. Notable shares of both newly insured and previously insured adults report problems paying their monthly premium, and newly insured adults were particularly cost-sensitive in choosing their health plan. These patterns may indicate that while coverage can ameliorate some of the financial challenges that low- and moderate-income adults face, many will continue to face financial challenges in other areas of their lives.

Coverage facilitates access to care, but some newly insured adults need additional support in navigating the health system and getting linked to care. Like outcomes related to medical costs, survey results show that newly insured adults fared better than uninsured adults in access to care, including having a regular provider, receiving preventive care, not postponing care, and have effective communication with their provider. However, on some measures, newly insured adults reported more problems than their counterparts who have had coverage since before 2014: for example, they were less likely to have a regular provider, more likely to not get needed care, and more likely to say a provider would not take them as a patient due to insurance. These differences likely reflect a range of factors, including limited networks, problems navigating the health system, misunderstanding about how to use coverage and when to seek care, or concerns about out-of-pocket costs. While coverage facilitates access to care, it may not automatically or immediately link newly insured adults into care in the same way that adults who have had insurance for quite some time are. Ongoing monitoring of newly insured adults’ access and utilization is important to assess whether this population continues to face challenges or whether these differences subside over time.

Among the newly insured population, there were few differences in outcomes by type of coverage. The ACA builds on the existing employer-based system to create coverage options for people across the income spectrum, including Medicaid (for people at the lowest incomes) and subsidies for Marketplace coverage (for people with middle-income). Medicaid is designed to serve a low-income population, with very limited cost sharing and broad benefits; Marketplace coverage is designed to serve those with middle incomes, with premium and cost-sharing support for people with income at the lower range of eligibility. Through some have expressed concern that some gaining coverage under the ACA are required to enroll in Medicaid versus Marketplace coverage, survey findings indicate very few differences in outcomes for these two groups. For example, there were no differences in plan ratings or problems with coverage, protection from medical bills, or access to care. The differences that were seen (for example, that newly insured adults with Medicaid are sicker, less likely to be in a working family, and are more generally financially insecure) largely reflect Medicaid’s role in targeting lowest income and most vulnerable. However, on measures of how coverage works for enrollees, Medicaid and Marketplace coverage fared about equally well and generally as well as employer-based coverage.