State Variations in the Role of the Reproductive Health Safety Net for Contraceptive Care Among Medicaid Enrollees

Key Takeaways

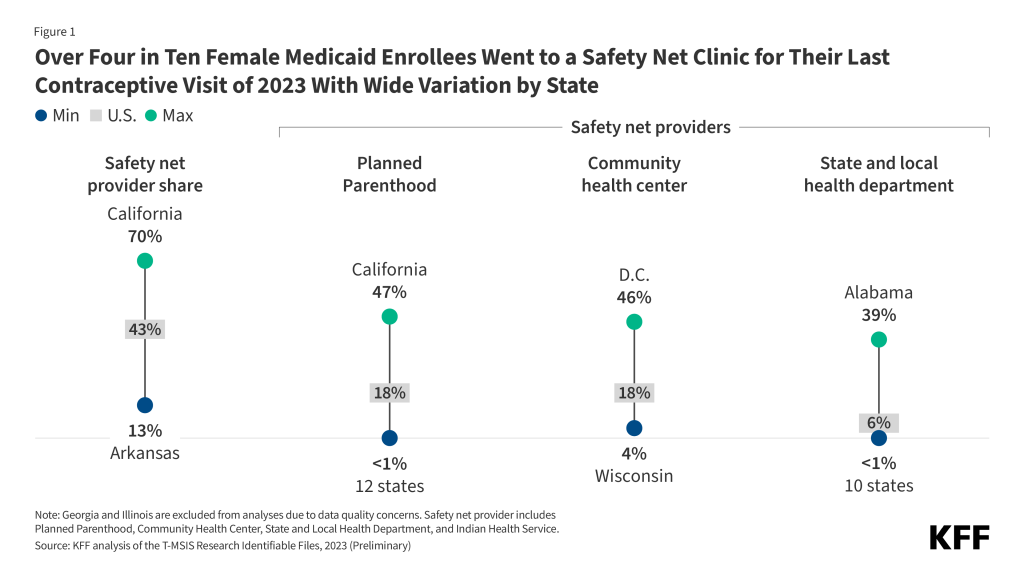

- Medicaid is a major source of coverage for contraceptive care for millions of people. Many Medicaid patients rely on a range of safety net providers including Planned Parenthood clinics, community health centers, state and local health departments, and Indian Health Services for their contraceptive care. The composition of the safety net and the relative role of the different providers vary considerably from state to state.

- Safety net providers served over four in ten (43%) female Medicaid enrollees seeking contraceptive care nationally, but there were considerable variations by state in the share of patients they served. While the safety net plays an important role for Medicaid enrollees, over half (54%) of female Medicaid enrollees had their last contraceptive visit at an office-based provider or outpatient clinic.

- Community health centers (CHC) accounted for 18% of recent contraceptive visits but the state range was sizable with 46% of female patients in DC had their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a CHC and 38% in Rhode Island. In contrast to only 4% in Wisconsin and 6% in Utah, North Dakota, North Carolina and Minnesota were seen at a CHC.

- Planned Parenthood was also an important source of contraceptive care for Medicaid enrollees (18%) but ranged widely by state. In California, 47% of female Medicaid enrollees had their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a Planned Parenthood, compared to none in Arkansas, Mississippi, North Dakota, Wyoming, West Virginia and Texas.

- Health departments (6%) and Indian Health Services (1%) often play a smaller role nationally, but these shares can mask the important role they play in some states as a major provider of contraceptive care. For example, 39% of female Medicaid enrollees in Alabama got their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a health department and 37% of enrollees in Alaska through Indian Health Services.

- The relative role of safety providers is likely to change in the coming years spurred by the Federal Medicaid payment ban on Planned Parenthood, uncertainty regarding the future of Title X, growth in the uninsured projected as result of the 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation law.

For millions of low-income people, Medicaid is a major source of coverage for their contraceptive care. It is the largest national, publicly funded program that finances family planning care and provides a key source of revenue for the vast network of safety net providers that provide reproductive and sexual health care services. Over the past year, a combination of actions by the Trump Administration, Supreme Court rulings, and new federal laws have begun to constrict the resources available to many of the providers that comprise this network. These actions have considerable implications for the future of this safety net and ultimately for access to contraceptive care for low-income people.

The reproductive health safety net is composed of clinics that receive public funds to provide sexual and reproductive health services, and includes Community Health Centers (CHCs), health departments, Planned Parenthood clinics, Indian Health Services, and other publicly funded clinics. These sites provide family planning services including contraception, sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, and cervical and breast cancer screening and serve large populations of low-income individuals on Medicaid billing the program for the sexual and reproductive health services they provide to enrollees. Many of these sites also receive funding support from federal programs to serve low-income uninsured individuals including the Title X family planning program, federal Health Center Program and the Indian Health Service.

The most immediate impact on funding for safety net providers has been through the Courts and Congress and has disproportionately but not exclusively affected Planned Parenthood clinics. In June 2025, the Supreme Court ruling in Medina v Planned Parenthood opened the door for states to choose to disqualify Planned Parenthood clinics from participating as a Medicaid provider. This ruling was followed by the July 2025 enactment of the 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation Law which stripped federal Medicaid funding for one year to Planned Parenthood clinics as well as a handful of other family planning providers that also offered abortion services to their patients. The provision of the new law is being legally challenged in three separate cases making their way through federal courts, but currently, the funding ban is in effect across the country. In addition to actions directed to providers, the new law will also require certain Medicaid enrollees to meet work requirements as a condition of eligibility, a new policy that is estimated by the Congressional Budget Office to increase the number of uninsured by millions in the next ten years.

Using the 2023 Transformed Medicaid Statistical Information System Research Files (TAF), a database of all Medicaid claims, KFF conducted an analysis to look at where reproductive age females received their last contraceptive care service by state with the goal of better understanding the role of the different types of reproductive health safety net providers in providing contraceptive care to females with Medicaid. Since people can receive contraceptive care at multiple locations in the span of a year, this analysis focused on the last location where Medicaid enrollees who received contraceptive care got their services in 2023. Since contraceptive patients can have multiple visits in the same year, this approach eliminates duplication in counting enrollees for one calendar year. This analysis specifically examines the number of Medicaid enrollees who obtained their most recent contraceptive visit at the following sites: Planned Parenthood, health centers including federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and Look-alike health centers, state and local health departments, Indian Health Services, other sites (i.e., emergency room, retail clinics, pharmacies), and office-based providers/outpatient clinics (i.e., offices, independent clinics, outpatient hospital clinics, ambulatory surgical centers, and birthing centers). We then looked at the distribution of place of service for contraceptive care by state. Detailed methods are presented in Appendix 1.

U.S. Profile

Nationally, Medicaid enrollees rely on a broad range of safety net providers for their contraceptive care. Over four in ten (43%) received their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a safety net provider, including a Planned Parenthood clinic, a community health center, a state and local health department, or Indian Health Services (Figure 1).

Planned Parenthood

Planned Parenthood clinics are specialized reproductive health providers that provide the full range of contraceptive methods, STI testing, pap smears, breast exams, preventive care, and often abortion services. Despite the fact that there are fewer Planned Parenthood clinics than other safety net providers such as community health centers and state health departments, research has shown that they provide this specialized care to a high volume of patients relative to other providers. Not all states have Planned Parenthood clinics. Many states, with the support of abortion opponents, have tried to exclude Planned Parenthood clinics from their Medicaid program, largely due to opposition to including a health care provider that also provides abortion. While these efforts have been challenged by the health care provider, the Supreme Court’s June 2025 decision in Medina v Planned Parenthood South Atlantic has opened the door for states to ban Planned Parenthood from participating in their Medicaid programs. This was followed in July 2025 with the enactment of the 2025 Federal Reconciliation Bill which imposed a one year ban on Federal Medicaid funding that had a direct impact on Planned Parenthoods’ ability to participate in Medicaid for one year. In recent years, many Planned Parenthood sites have closed due to funding cuts, low Medicaid reimbursement levels, state abortion policies, and a loss of federal funds with more closures anticipated in the coming years if federal funds are not restored.

The share of female Medicaid recipients who received their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a Planned Parenthood clinic was 18% across the U.S. and ranged from 0% in states that do not have a Planned Parenthood presence or ban Planned Parenthood from participating in their Medicaid program (Arkansas, Mississippi, North Dakota, Texas, Wyoming) to almost half (47%) of California female Medicaid recipients who received their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a Planned Parenthood clinic (Figure 2). California has the largest Medicaid enrollment in the country and the nation’s largest Planned Parenthood clinic network but has also seen the largest number of Planned Parenthood clinic closures this year, with 6 clinics closing since the start of 2025. Some states like Louisiana have seen all of their Planned Parenthood clinics close this year. In Wisconsin, one in three (32%) female Medicaid clients received their last contraceptive care in 2023 at a Planned Parenthood clinic. Planned Parenthood clinics also provide contraceptive services to 20% Medicaid patients in Connecticut, Oregon and Washington State. As clinics have closed across the U.S. in the last several years, the share of Medicaid enrollees that rely on Planned Parenthood has likely decreased since 2023.

Community Health Centers

Community health centers comprise a national network of safety net providers that receive federal grants to provide a range of primary health services as well as other services including dental and mental health care to low-income people. Community health centers as defined in this analysis include mostly federally qualified health centers (FQHCs), as well as FQHC look-alike clinics. Although the network is vast (nearly 18,000 service sites across the U.S.), not all these sites provide contraceptive care or may not provide the full range of contraceptive services to their patients. Previous research finds that only 1 in 4 community health centers offer their patients onsite access to all of the most effective family planning methods. Community health centers have historically served much smaller volumes of contraceptive clients, and it is estimated they would have to increase their contraceptive client caseloads by 56% to make up for the loss of Planned Parenthood clinics as a site of care for Medicaid enrollees.

The share of female Medicaid recipients who received their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at a community health center across the U.S. was 18% and ranged from a low of 4% in Wisconsin to a high of 46% in D.C. (Figure 3). In states where smaller shares of Medicaid patients rely on community health centers, these providers may face difficulties in ramping up the availability of services to meet a higher demand for time-sensitive services if there are fewer options for contraceptive care when other clinics close or when they are faced with an increasing number of uninsured patients due to coverage loses through ACA enrollment decreases and Medicaid disenrollment.

State and Local Health Departments

State and local health departments comprise another important part of the reproductive health safety net in several states, and many, particularly in the South, receive Title X funding to provide family planning services to low-income and insured people in their community. Health departments have historically made up a smaller percentage of publicly supported family planning clinics and served fewer patients than Planned Parenthood clinics and federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). Of the 4.7 million women who obtained contraceptive care from publicly supported clinics in 2020, 13% received care from a health department. Similar to FQHCs, health departments are also less likely to provide the full range of contraceptive methods. However, recent research has shown that health departments perform as well or better than FQHCs on providing patient-centered contraceptive care, like prescribing at least 12 months of oral contraception at initial visit and providing same-day IUDs and implants.

This analysis finds that the role of health departments in providing contraceptive services to Medicaid enrollees nationally was 6%, it varied considerably from state to state, ranging from a high of 39% in Alabama to 0% in a number of states where health departments either do not provide or bill for health services or contraceptive care (Figure 4). Alabama’s entire Title X network is comprised of health departments, as are most of South Carolina and Louisiana’s Title X networks, which may explain the large share of Medicaid recipients who get their contraceptive care at a health department. In general, states in the Southeastern U.S. provided contraceptive care to larger shares of female Medicaid enrollees through health departments than in other parts of the country.

Indian Health Services

Indian Health Services (IHS) may not play a large role in providing contraceptive care across the U.S., but in states with larger American Indian and Alaska Native populations, they play a major role. Federal regulations require IHS to cover health promotion and disease prevention services, which include family planning services and STI services with no cost-sharing to members or descendants of federally recognized Tribes who live on or near federal reservations.

In Alaska, more than one in three (37%) female Medicaid enrollees received their last contraceptive visit of 2023 at an Indian Health Services site (Figure 5). One in six (16%) female Medicaid enrollees received their last contraceptive care at Indian Health Services in South Dakota. Indian Health Services also played a larger role in Arizona, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Montana. Many of these sites bill Medicaid for services provided to Native Americans in addition to grant funding they receive through IHS. Reductions in Medicaid enrollment anticipated as a result of the Medicaid work requirements in the 2025 Federal Reconciliation law and subsequent increases in the share of patients who are uninsured means that these sites could have fewer resources to provide contraceptive services to their patients.

Office-Based Providers/Outpatient Clinics

Given the vast proliferation of managed care in the Medicaid program, providers including those in private practice, independent clinics, outpatient or inpatient hospital departments, or ambulatory surgical centers or birthing centers provide the majority of contraceptive care to Medicaid enrollees. Most individuals with Medicaid go to an office-based provider or outpatient clinic that accepts Medicaid patients for their contraceptive care. With a weakening of the reproductive health safety net and fewer options for Medicaid enrollees to receive contraceptive care, office-based providers and outpatient clinics may see an influx of patients who can no longer go to their usual contraceptive care provider or be seen in a timely way.

The national share of female Medicaid enrollees receiving contraceptive care at an office-based provider/outpatient clinic was 54%. This ranged from a low of 25% in California, which has a large network of reproductive health safety net providers, to a high of 86% in Arkansas (Figure 6). It should be noted that office-based/outpatient providers may see a decrease in Medicaid patients in the future if enrollees start to lose Medicaid coverage due to work requirements and administrative lapses in coverage. Also, care at these sites may be unaffordable for those who are uninsured. A 2024 KFF survey found that 20% of uninsured females reported that they had to stop using a method of birth control because of cost.

Looking Ahead

Recent policy changes under the current Trump Administration have resulted in cuts to federal funding for reproductive health safety net providers through Title X and Medicaid. This has made it challenging for some of these clinics to continue operating at full capacity, and in some cases stay open. In April 2025, 16 of the 86 Title X grantees, including all the Planned Parenthood grantees had their Title X funding withheld by the Trump Administration. While some grantees eventually received partial funding months later, many clinics went several months without any Title X funds and Planned Parenthood grantees have not received any Title X funds this year. This funding uncertainty has left some of these clinics facing difficult decisions regarding their ability to continue to operate without knowing when or if they would ever receive their Title X funding. In addition, the future of the Title X family planning program is unclear. Nearly all the staff of the federal program have been laid off during the shutdown, and the Trump administration did not include any support for the program in its FY 2026 budget proposal to Congress earlier this year.

With the June 2025 Supreme Court ruling in Medina v. Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, the door was opened for states to disqualify Planned Parenthood from participating as providers in their Medicaid programs. While this case narrowly focused on South Carolina, it is anticipated that many states, even those where abortion is banned, will drop Planned Parenthood from their Medicaid programs because they provide abortion services in other states. Federal Medicaid funds have been prohibited from paying for abortion services for decades under the Hyde Amendment, and this case allows states to choose to block Planned Parenthood from participating in Medicaid for providing other services, including contraceptive and preventive care. This state choice was effectively nationalized by the 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation Law which prohibits “specialized” reproductive health clinics that are classified as essential community providers, provide abortion services, and received over $850,000 in Medicaid revenues from receiving any federal Medicaid reimbursement for providing non-abortion-related family planning services to individuals with Medicaid. This includes nearly all Planned Parenthood clinics as well as Maine Family Planning and Health Imperatives in Massachusetts. While this law is currently being challenged in multiple lawsuits, federal Medicaid funding is currently blocked and no longer flows to these providers for any services they provide to Medicaid enrollees. Some states have provided funds to Planned Parenthood and other affected safety net providers, but there is no guarantee that the funding will continue in future years, and funding levels often do not fill the gap. Finally, while this is a one year ban, there are already efforts in place by abortion opponents to extend this policy next year through another reconciliation vehicle.

The 2025 Federal Budget Reconciliation Law is also projected to increase the number of individuals without insurance by 10 million over the next 10 years, which is expected to place increased pressure on the remaining reproductive health care safety net given its role providing care to uninsured patients. Combined, these policies and cuts to funding for family planning care are expected to have a direct impact on the availability of affordable and effective contraception to those who want or need it and will likely increase the number of individuals living in contraceptive deserts and who potentially experience an undesired pregnancy. The impacts of these policies will vary considerably from state to state by provider type.

Methods

Medicaid Claims Data: This analysis used two files from the 2023 T-MSIS Analytic Files (TAF): Other Header and Other Line Files (outpatient services). The analysis was limited to outpatient services because place of service (POS_CD) is only included in the Other Header File. Some patients who received their last contraceptive care while in an inpatient setting are not captured by this analysis.

State Exclusion Criteria: Georgia and Illinois were excluded due to data quality issues with NPI.

Identifying Contraceptive Care in Medicaid Claims Data: Contraceptive claims from the Other Line file were included if they could be linked by CLM_ID to the Other Header File. We looked for all contraceptive diagnosis and procedure codes from the Other Header and Other Line File (codes available upon request).

Defining Site of Care in Medicaid Claims Data: Then the following codes were used to define the site of care on the contraceptive claim: BLG_PRVDR_NPI, DRCTNG_PRVDR_NPI, RFRG_PRVDR_NPI, SPRVSNG_PRVDR_NPI, SRVC_PRVDR_NPI, POS_CD, PGM_TYPE_CD, and BNFT_TYPE_CD. A hierarchy of contraceptive care sites was created because a single claim can have multiple codes describing different sites. There were a number of instances where contraceptive claims had laboratory as a place of service because contraceptive counseling was provided with the lab service, such as a sexually transmitted infection test. Therefore, we applied the hierarchy to all of the claims on a service day for that individual to capture whether an individual went to another location on the same day that would have likely ordered the lab service.

Office-based providers/Outpatient clinics were classified after all other sites of care were identified. The following hierarchy and codes were used to define each site of care (see Appendix Figure 1 for distributions by state):

- Planned Parenthood: any Planned Parenthood NPI as identified through the NPPES Registry included in BLG_PRVDR_NPI, DRCTNG_PRVDR_NPI, RFRG_PRVDR_NPI, SPRVSNG_PRVDR_NPI, SRVC_PRVDR_NPI.

- Community Health Centers: POS_CD 50 (Fed Qualified Health Ctr.), PGM_TYPE_CD 04 (Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC)), BNFT_TYPE_CD 004 (FQHC services), BLG_PRVDR_NPPES_TXNMY_CD 261QF0400X (Clinic/Center – Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)), BLG_PRVDR_TXNMY_CD 261QF0400X (Clinic/Center – Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)), or an FQHC or FQHC look alike NPI from the HRSA Health Center Directory or NPPES Registry with taxonomy 261QF0400X (Clinic/Center – Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC)) for BLG_PRVDR_NPI, DRCTNG_PRVDR_NPI, RFRG_PRVDR_NPI, SPRVSNG_PRVDR_NPI, SRVC_PRVDR_NPI

- Health Department: POS_CD 71 (Public Health Clinic) or 72 (Rural Health Clinic), PGM_TYPE_CD 03 (Rural Health Clinic (RHC)), or BNFT_TYPE_CD 003 (Rural health clinic services)

- Indian Health Services: POS_CD 05 (Indian Health Service – Free-standing Facility), 06 (Indian Health Service – Provider-based Facility), 07 (Tribal 638), 08 (Tribal 638 Provider-based Facility); PGM_TYPE_CD 05 (Indian Health Services (IHS)); BNFT_TYPE_CD 061 (Indian Health Services and Tribal Health Facilities); or TOS_CD 127 (Indian Health Service (IHS))

- Other: Other services include places like retail clinics, pharmacies, urgent care, schools, telehealth, and laboratories. Across the states, the percentage of female Medicaid enrollees who received their last contraceptive visit in an “other” location ranged from 0% to 9%.

- Office-based Providers/Outpatient Clinics: POS_CD: 11 (Office), 19 (Off Campus – Outpatient Hospital), 21 (Inpatient Hospital), 22 (Outpatient Hospital), 24 (Ambulatory Surgical Center), 25 (Birthing Center), 49 (Independent Clinic)