Impact of Key Provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 COVID-19 Relief on Marketplace Premiums

Data Note

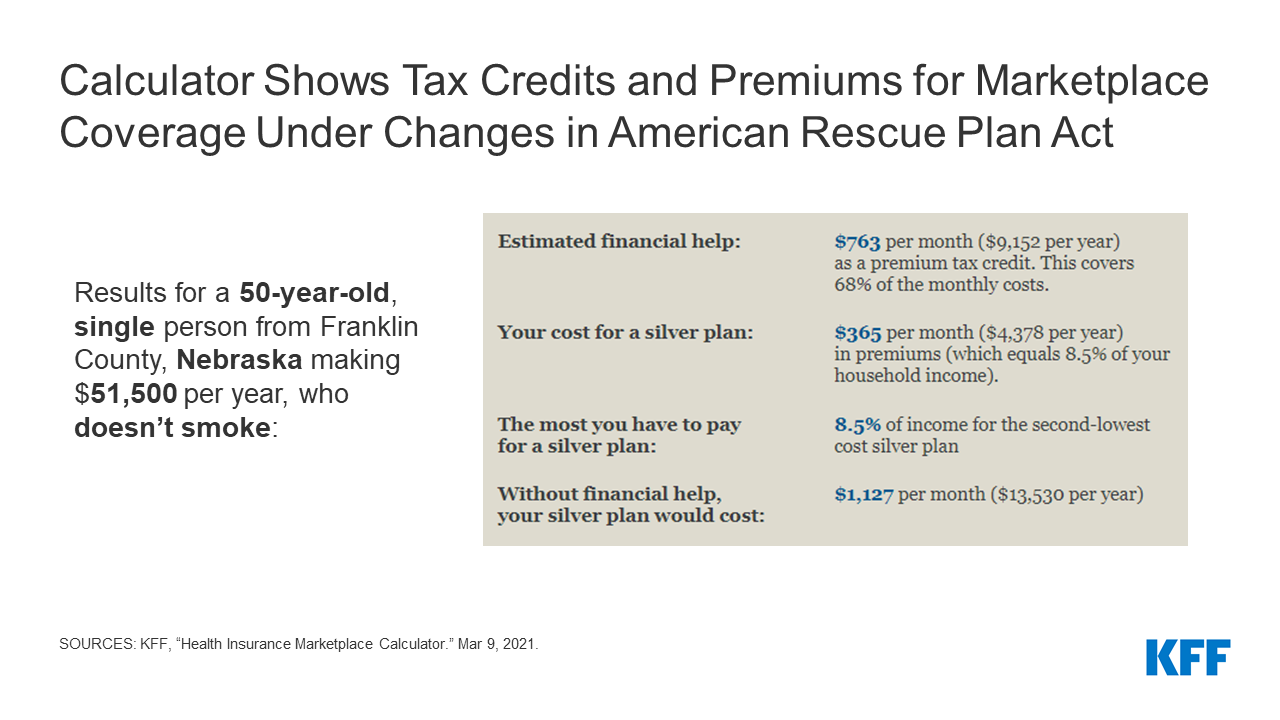

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made premium tax credits available to people purchasing health coverage on the Marketplaces, but generally only when their incomes fall between 100% and 400% of the federal poverty level. These subsidies work by capping what an enrollee must spend on a silver benchmark plan premium at no more than a certain percentage of the enrollee’s household income. The premium tax credit amount equals the difference between the actual benchmark plan premium for that individual and the required contribution. The tax credit can be applied to any metal level plan.

However, a sharp cliff exists at 400% of the poverty level. Under the ACA before any legislative changes, a 60-year-old making $50,000 per year (392% of poverty) would pay no more than $410 per month for a benchmark silver plan (9.83% of her income, after receiving an average subsidy of $548 per month). However, if her income crossed above $51,040 per year (400% of poverty), health insurance would become much more expensive. For example, at an income of $52,000 per year (408% of poverty), a 60-year-old would pay the full-priced premium, which, for a benchmark silver plan, averages $957 per month nationwide (22% of her income). This doubling of the premium payment for people with incomes just over 400% of poverty has been called the “subsidy cliff,” as shown in the blue line in Figure 1 below.

Additionally, there are millions of uninsured people who could be getting subsidized coverage on the ACA Marketplaces, but have not taken advantage of this financial help. In many cases, it may be that the financial help available to them is not sufficient to make the premium or the deductible affordable.

COVID-19 Relief Marketplace Subsidy Expansions

The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (COVID-19 relief) law passed in March 2021 expands Marketplace subsidies above 400% of poverty and also increases subsidies for those making between 100% and 400% of the poverty level, for two years (2021 and 2022), consistent with what President Biden proposed during his campaign.

These additional subsidies will yield substantially lower premium payments for the vast majority of the nearly 15 million uninsured people who are eligible to buy on the Marketplace and the nearly 14 million people insured on the individual market. With some exceptions (in the case of the highest income enrollees whose premiums may not be high enough to qualify for a subsidy), most of these 29 million people could see lower health insurance premiums as a result of these subsidies, and many could also afford lower deductible plans. However, it is far from certain how many people will take advantage of the new financial assistance.

Table 1 below compares the ACA and COVID-19 relief subsidy schedule, both of which are benchmarked to the premium of the second-lowest cost silver plan. The COVID-19 relief subsidy schedule increases subsidies across the board, notably extending them for the first time to people with incomes over 400% of the poverty level and guaranteeing access to a plan with a zero dollar premium payment for people with incomes between 100-150% of poverty. The COVID-19 relief law also expands Marketplace subsidies to people receiving unemployment insurance (UI), which we discuss more below.

| Table 1: Percent of Income Paid for Marketplace Benchmark Silver Premium, by Income | ||

| Income (% of poverty) | Affordable Care Act(before legislative change) | COVID-19 Relief (current law 2021-2022) |

| Under 100% | Not eligible for subsidies* | Not eligible for subsidies** |

| 100% – 138% | 2.07% | 0.0% |

| 138% – 150% | 3.10% – 4.14% | 0.0% |

| 150% – 200% | 4.14% – 6.52% | 0.0% – 2.0% |

| 200% – 250% | 6.52% – 8.33% | 2.0% – 4.0% |

| 250% – 300% | 8.33% – 9.83% | 4.0% – 6.0% |

| 300% – 400% | 9.83% | 6.0% – 8.5% |

| Over 400% | Not eligible for subsidies | 8.5% |

| NOTES: *Lawfully present immigrants whose household incomes are below 100% FPL and are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid are eligible for tax subsidies through the Marketplace if they meet all other eligibility requirements.**In the COVID-19 relief law, lawfully present immigrants in states that have not expanded Medicaid would continue to be eligible for marketplace subsidies. In addition, people receiving Unemployment Insurance (UI) are treated as though their income is no more than 133% of poverty for the purposes of the premium tax credit. This could extend premium tax credits to some individuals with incomes below poverty.SOURCE: KFF | ||

Removing the Subsidy Cliff

We estimate that there are about 8 million people who either are buying unsubsidized plans or faced paying full-price for ACA coverage before the COVID-19 relief legislation went into effect. This included an estimated 3.4 million uninsured people who fell into the subsidy cliff (i.e. had incomes too high to qualify them for subsidies under the ACA). Additionally, it included about 3.3 million people buying off-exchange coverage and 1.4 million people buying unsubsidized on-exchange plans, presumably because many were ineligible to buy subsidized coverage.

By extending eligibility for Marketplace subsidies above 400% of poverty, the COVID-19 relief law flattens out the ACA’s subsidy cliff and lowers premiums for virtually everyone already eligible for Marketplace subsidies. As shown in Figure 1, older people with incomes just above 400% of poverty ($51,040 for a single individual) would receive substantial new subsidies. The benefit would gradually phase out at higher incomes, as benchmark silver premiums no longer cross the 8.5% of income threshold.

As noted above, older adults with incomes above 400% of poverty would generally see some of the most significant savings from the COVID-19 relief law. Uninsured people in the subsidy cliff tend to be older, on average, than those eligible for subsidies, because premiums were so high for this group under the ACA. Figure 2 below shows the amount of savings available to older enrollees currently falling in the subsidy cliff. Compared to current premium payments, a 60-year-old with a $55,000 income would pay 77% less for a bronze plan ($146 vs. $634 per month), 56% less for a benchmark silver plan ($390 vs. $887 per month), and 52% less for a gold plan ($453 vs. $951 per month), on average, under the COVID-19 Relief law. Many young adults with incomes above 400% of poverty who are currently in the subsidy cliff would also see savings under the COVID-19 relief law, but those savings would be more modest (a 6-9% drop, depending on the metal level, for an average 27 year old).

Expanded Subsidies for Those Already Eligible

While removing the subsidy cliff would provide some of the largest drops in premium payments, the COVID-19 relief’s additional subsidies to those already eligible are also substantial, particularly because they would guarantee zero-premium silver plans to millions of low-income enrollees. At least 3.4 million of the lowest income enrollees would see a 100% decrease in their premium contribution.

The COVID-19 relief sets benchmark silver premium contributions at $0 of income for all enrollees with incomes below 150% of poverty. These zero-premium silver plans would also come with cost-sharing reductions that lower deductibles substantially. Enrollees with incomes between 100-150% of poverty would become eligible for a zero-premium silver plan with an average deductible of $177.

Most of these enrollees would have already been eligible for a zero-premium bronze plan under the ACA, but bronze plans have a typical deductible of about $6,900. For the same $0 premium, the lowest-income Marketplace enrollees could have a deductible that is 97% lower under COVID-19 relief law.

People Receiving Unemployment Insurance

The COVID-19 relief law makes special considerations for people approved to receive or receiving unemployment compensation at any point in 2021. Under the COVID-19 relief law, if a person is receiving unemployment compensation and she qualifies to purchase insurance on the Marketplace, she and any eligible dependents can get a silver plan with a $0 premium. That is because, under the proposal, any household income above 133% of poverty is not considered in the calculation of her premium tax credit if she receives unemployment insurance.

For people receiving unemployment compensation at any point in 2021, their income up to 133% of poverty is counted in determining eligibility for a cost-sharing reduction, which is only available to people with incomes between 100% and 250% of poverty. That is, a person with income, including unemployment compensation, of 260% of poverty would receive a premium and cost-sharing reduction subsidy as if her income is 133% of poverty. A person receiving unemployment income would still need to attest that they do not have an affordable offer of employer-sponsored insurance from their spouse or other family member. As the COVID-19 relief law does not change the so-call “family glitch” in the ACA, if an employer offer is deemed affordable (9.83% of household income for 2021 for self-only coverage), this may disqualify people receiving unemployment income from receiving ACA subsidies if they still have a working family member with an employer offer.

State-Level Differences

As is the case under the ACA, the amount of the subsidy in the COVID-19 relief law would vary by age, income, and geography. Tables in the Appendix show premium payment at the national level for various age and income scenarios, and at the state level for a 60-year-old currently in the ACA subsidy cliff. Note that all tables take into account additional state subsidies that are already provided in California and Vermont, so the typical savings would be even greater if those state were excluded.

Older adults in the ACA subsidy cliff who are living in states with high premiums would see the largest premium savings from the COVID-19 relief law. As shown in the map below, a 60-year-old making $55,000 per year living in Wyoming, West Virginia, South Dakota, Nebraska, Connecticut, or Alabama would save over 70% on the benchmark silver plan, on average. Older adults previously in the ACA subsidy-cliff in several states would even become eligible for free bronze plans, as shown in the state-level Appendix table.

Implications for Federal Government Costs and the Uninsured Rate

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) project that the enhanced premium tax credits in the original House COVID-19 relief proposal would increase federal deficits by $34.2 billion over ten years (including an increase in direct federal spending of $22.0 billion and a reduction in revenues of $12.2 billion). Additionally, CBO and JCT expect the enhanced subsidies for people receiving unemployment insurance to add another $4.5 billion over the next ten years (including an increase in outlays of $2.4 billion and a decrease in revenues of $2.1 billion).

CBO projections are generally over a 10-year period. Because the enhanced subsidies only last two years, though, most of the costs would be concentrated in 2021 and 2022. However, CBO and JCT expect some new enrollees to continue purchasing subsidized Marketplace coverage for a few years, even if those enrollees are no longer receiving enhanced subsidies.

The CBO and JCT estimate that, in 2022, 1.7 million people would gain coverage through the Marketplace. They estimate that new enrollees will account for $13.0 billion in federal costs, with the remaining going to enhanced premium tax credits for existing enrollees.

Methods

We analyzed data from the 2021 Individual Market Medical files to determine premiums and the benchmark amounts to calculate premium tax credits for the scenarios presented. Premiums for state-based Marketplaces are from KFF analysis of data received from Massachusetts Health Connector, Covered CA, and KFF analysis of data published by HIX Compare from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. This analysis only includes on-exchange plans. The premium caps used to model premiums under the ACA and the COVID-19 relief law are shown in Table 1 above.

All averages are weighted by county-level 2020 plan selections. 2020 plan selections come from the 2020 Marketplace Open Enrollment Period County-Level Public Use file provided by CMS. In states running their own exchanges, we gathered county-level plan selection data where possible and otherwise estimated county plan selections based on the county population in the 2010 Census and total state plan selections in the 2020 OEP State-Level Public Use File provided by CMS.

Premium Interactive

Appendix

| Appendix Table 1: Change in Monthly Benchmark Premium under COVID-19 Relief Law | |||||||

| 27-year-old | 40-year-old | 60-year-old | |||||

| Income | FPL | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief |

| $20,000 | 157% | $72 | $4 | $72 | $4 | $72 | $4 |

| $25,000 | 196% | $126 | $37 | $126 | $37 | $126 | $37 |

| $30,000 | 235% | $193 | $85 | $193 | $85 | $193 | $85 |

| $35,000 | 274% | $261 | $145 | $261 | $145 | $261 | $145 |

| $40,000 | 313% | $316 | $211 | $323 | $211 | $324 | $211 |

| $45,000 | 353% | $341 | $274 | $362 | $274 | $366 | $274 |

| $50,000 | 392% | $354 | $330 | $394 | $344 | $408 | $346 |

| $60,000 | 470% | $373 | $357 | $450 | $404 | $909 | $425 |

| $70,000 | 549% | $373 | $367 | $450 | $430 | $924 | $496 |

| $80,000 | 627% | $373 | $371 | $450 | $442 | $933 | $566 |

| $90,000 | 705% | $373 | $373 | $450 | $447 | $933 | $636 |

| $100,000 | 784% | $373 | $373 | $450 | $449 | $933 | $701 |

| NOTES: This table shows enrollment-weighted average premiums for the lowest-cost bronze plan. ACA premiums account for additional financial assistance provided to enrollees in California, Vermont, and Massachusetts.SOURCE: KFF analysis of data from Healthcare.gov, Massachusetts Health Connector, and HIX Compare from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. | |||||||

| Appendix Table 2: Change in Monthly Bronze Premium under the COVID-19 Relief Law | |||||||

| 27-year-old | 40-year-old | 60-year-old | |||||

| Income | FPL | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief |

| $20,000 | 157% | $4 | $0 | $2 | $0 | $1 | $0 |

| $25,000 | 196% | $37 | $0 | $24 | $0 | $3 | $0 |

| $30,000 | 235% | $92 | $7 | $74 | $3 | $12 | $0 |

| $35,000 | 274% | $158 | $49 | $139 | $33 | $42 | $2 |

| $40,000 | 313% | $215 | $111 | $202 | $92 | $89 | $17 |

| $45,000 | 353% | $240 | $172 | $240 | $153 | $124 | $50 |

| $50,000 | 392% | $253 | $229 | $272 | $222 | $163 | $107 |

| $60,000 | 470% | $272 | $256 | $328 | $282 | $656 | $178 |

| $70,000 | 549% | $272 | $266 | $328 | $308 | $671 | $246 |

| $80,000 | 627% | $272 | $270 | $328 | $320 | $680 | $315 |

| $90,000 | 705% | $272 | $272 | $328 | $325 | $680 | $384 |

| $100,000 | 784% | $272 | $272 | $328 | $327 | $680 | $449 |

| NOTES: This table shows enrollment-weighted average premiums for the lowest-cost bronze plan. ACA premiums account for additional financial assistance provided to enrollees in California, Vermont, and Massachusetts.SOURCE: KFF analysis of data from Healthcare.gov, Massachusetts Health Connector, and HIX Compare from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. | |||||||

| Appendix Table 3: Change in Monthly Gold Premium under the COVID-19 Relief Law | |||||||

| 27-year-old | 40-year-old | 60-year-old | |||||

| Income | FPL | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief |

| $20,000 | 157% | $96 | $33 | $101 | $40 | $137 | $80 |

| $25,000 | 196% | $150 | $62 | $155 | $68 | $190 | $106 |

| $30,000 | 235% | $220 | $112 | $225 | $118 | $259 | $154 |

| $35,000 | 274% | $287 | $172 | $293 | $177 | $326 | $212 |

| $40,000 | 313% | $343 | $238 | $355 | $243 | $388 | $277 |

| $45,000 | 353% | $368 | $300 | $393 | $306 | $430 | $339 |

| $50,000 | 392% | $381 | $357 | $426 | $375 | $472 | $410 |

| $60,000 | 470% | $400 | $384 | $482 | $436 | $972 | $489 |

| $70,000 | 549% | $400 | $394 | $482 | $462 | $988 | $560 |

| $80,000 | 627% | $400 | $398 | $482 | $474 | $996 | $630 |

| $90,000 | 705% | $400 | $400 | $482 | $479 | $996 | $699 |

| $100,000 | 784% | $400 | $400 | $482 | $481 | $996 | $765 |

| NOTES: This table shows enrollment-weighted average premiums for the lowest-cost bronze plan. ACA premiums account for additional financial assistance provided to enrollees in California, Vermont, and Massachusetts.SOURCE: KFF analysis of data from Healthcare.gov, Massachusetts Health Connector, and HIX Compare from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. | |||||||

| Appendix Table 4: Average Change in Monthly Premium for Enrollee at $55,000 Income (430% of Poverty) Under the COVID-19 Relief Law, by State | ||||||

| Lowest-Cost Bronze | Benchmark Silver | Lowest-Cost Gold | ||||

| State | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief | ACA | COVID-19 Relief |

| Alabama | $852 | $1 | $1,253 | $390 | $1,421 | $558 |

| Arizona | $726 | $198 | $925 | $390 | $1,175 | $640 |

| Arkansas | $684 | $238 | $836 | $390 | $1,059 | $613 |

| California | $349 | $176 | $566 | $390 | $605 | $428 |

| Colorado | $579 | $223 | $746 | $390 | $813 | $458 |

| Connecticut | $781 | $0 | $1,349 | $390 | $1,116 | $157 |

| DC | $726 | $221 | $894 | $390 | $929 | $424 |

| Delaware | $850 | $94 | $1,146 | $390 | $1,098 | $342 |

| Florida | $720 | $144 | $968 | $390 | $1,038 | $459 |

| Georgia | $738 | $162 | $966 | $390 | $982 | $406 |

| Idaho | $701 | $41 | $1,051 | $390 | $1,117 | $456 |

| Illinois | $716 | $210 | $897 | $390 | $1,016 | $509 |

| Indiana | $706 | $212 | $883 | $390 | $1,257 | $763 |

| Iowa | $660 | $13 | $1,110 | $390 | $941 | $221 |

| Kansas | $793 | $170 | $1,013 | $390 | $1,063 | $440 |

| Kentucky | $726 | $107 | $1,009 | $390 | $1,229 | $609 |

| Louisiana | $871 | $121 | $1,154 | $390 | $1,304 | $539 |

| Maine | $738 | $196 | $932 | $390 | $1,049 | $507 |

| Maine | $534 | $271 | $653 | $390 | $769 | $506 |

| Maryland | $471 | $123 | $738 | $390 | $695 | $347 |

| Massachusetts | $467 | $238 | $619 | $390 | $707 | $478 |

| Michigan | $542 | $196 | $738 | $390 | $785 | $437 |

| Mississippi | $864 | $279 | $974 | $390 | $1,153 | $569 |

| Missouri | $738 | $116 | $1,016 | $390 | $1,125 | $498 |

| Montana | $701 | $89 | $1,001 | $390 | $1,026 | $415 |

| Nebraska | $932 | $4 | $1,485 | $390 | $1,340 | $247 |

| Nevada | $594 | $150 | $834 | $390 | $1,003 | $559 |

| New Hampshire | $525 | $207 | $707 | $390 | $770 | $453 |

| New Jersey | $677 | $207 | $859 | $390 | $1,404 | $934 |

| New Mexico | $501 | $171 | $719 | $390 | $687 | $358 |

| New York | $430 | $223 | $597 | $390 | $709 | $502 |

| North Carolina | $742 | $64 | $1,095 | $390 | $1,101 | $395 |

| North Dakota | $579 | $0 | $1,047 | $390 | $918 | $261 |

| Ohio | $595 | $213 | $772 | $390 | $910 | $527 |

| Oklahoma | $780 | $63 | $1,177 | $390 | $1,065 | $287 |

| Oregon | $675 | $141 | $923 | $390 | $973 | $439 |

| Pennsylvania | $635 | $99 | $927 | $390 | $881 | $344 |

| Rhode Island | $491 | $139 | $742 | $390 | $719 | $367 |

| South Carolina | $697 | $86 | $1,005 | $390 | $1,090 | $474 |

| South Dakota | $965 | $57 | $1,312 | $390 | $1,385 | $463 |

| Tennessee | $722 | $152 | $983 | $390 | $1,197 | $604 |

| Texas | $640 | $113 | $917 | $390 | $911 | $383 |

| Utah | $578 | $22 | $956 | $390 | $980 | $413 |

| Vermont | $491 | $212 | $669 | $390 | $674 | $394 |

| Virginia | $760 | $134 | $1,016 | $390 | $984 | $358 |

| Washington | $595 | $163 | $821 | $390 | $895 | $463 |

| West Virginia | $1,266 | $281 | $1,375 | $390 | $1,752 | $767 |

| Wisconsin | $718 | $140 | $970 | $390 | $1,020 | $439 |

| Wyoming | $1,103 | $0 | $1,679 | $390 | $1,369 | $80 |

| NOTES: This table shows enrollment-weighted average premiums for the lowest-cost bronze plan, the second-lowest cost silver plan, and the lowest-cost gold plan in each county, based on premiums in effect in 2021. ACA premiums account for additional financial assistance provided to enrollees in California, Vermont, and Massachusetts.SOURCE: KFF analysis of data from Healthcare.gov, Massachusetts Health Connector, and HIX Compare from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. | ||||||