Introduction

Several recent policy proposals address the cost of prescription drugs to both consumers and payers. Though attention in current federal actions is largely focused on Medicare and private insurance drug prices, federal legislation also has been recently introduced or enacted that would affect Medicaid prescription drug policy. Most recently, the American Rescue Plan included a provision that would eliminate the Medicaid rebate cap and save $14.5 billion between 2021-2030.

Congress has already started hearings on other legislation to target drug prices and could include such proposals in forthcoming budget reconciliation bills. This brief analyzes leading federal approaches to address Medicaid prescription drug spending, discusses (where available) a range of cost estimates for each policy, and assesses what drives those estimates or where there is uncertainty in them. Key findings include (Table 1):

- The recently enacted policy to eliminate the Medicaid rebate cap is estimated to save $14.5 billion in federal Medicaid spending between 2021-2030 and $17.3 billion between 2021-2031, though savings are to some extent dependent on manufacturer response to the policy. Other policies to increase Medicaid rebates, for example by increasing the minimum rebate amount for certain drugs, would likely generate similar scale potential savings for the Medicaid program.

- Prohibiting spread pricing by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) would generate relatively small federal savings of nearly $1 billion over ten years, but the level of savings depends on state actions to address spread pricing and the extent of spread pricing across states. State estimates suggest larger savings than estimates of federal proposals.

- Allowing importation of drugs would likely result in significant federal savings, but these would be to programs other than Medicaid. Importation is unlikely to have a large effect on Medicaid spending.

- The “best price” requirement provides significant discounts for federal and state Medicaid drug spending and policies that modify or eliminate Medicaid best price rules are likely to increase federal spending on Medicaid but may result in savings for other payers.

| Table 1: Federal Approaches to Address Medicaid Prescription Drug Spending |

| Cost Estimates | Status of Proposal | Key Factors Impacting Estimates |

| Eliminate Medicaid Drug Rebate Cap | $17.3 billion in federal Medicaid savings over 2021-2031 (policy effective as of 2024) | Enacted in the American Rescue Plan (P.L. 117-2) | - Number and composition of drugs reaching the rebate cap

- Manufacturer response

|

| Limit or Prohibit PBM Spread Pricing | $929 million in federal Medicaid savings over 10 years | Included in H.R. 19; introduced in House and referred to Subcommittee on Health | - State actions to limit spread pricing

- Prevalence of spread pricing across states

|

| Eliminate or Modify Medicaid Best Price | Not likely to produce savings and may increase costs | Final rule issued December 2020; Biden Administration issued proposed rule delaying provisions on 5/28/2021 | - Which drugs are subject to best price changes

- Manufacturer behavior

|

| Increase Minimum Rebate Amount for Certain Drugs | $10 billion in federal Medicaid savings over 10 years | MACPAC adopted recommendations to increase rebate amounts on certain accelerated approval drugs | - Which drugs are subject to new minimum rebate

- Manufacturer response

|

| Allow Importation of Prescription Drugs | $7 billion in federal savings over 10 years (across all federal programs) | Biden administration has supported the importation rule in court but gave no timeline for approval of state proposals | - Which drugs are subject to importation

- If Medicaid is able to receive rebates in addition to importation discounts

|

| SOURCE: CBO, Estimated Budgetary Effects of H.R. 1319, American Rescue Plan Act of 2021,March 2021; CBO, Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act of 2019, March 2020; CBO, A Comparison of Brand-Name Drug Prices Among Selected Federal Programs, February 2021; KFF, Pricing and Payment for Medicaid Prescription Drugs, January 2020; MACPAC High-Cost Specialty Drugs: Review of Draft Chapter and Recommendations, April 2021; CBO, S. 469, The Affordable and Safe Prescription Drug Importation Act, July 2017. |

1. Eliminate the Medicaid Drug Rebate Cap

Recent federal legislation has changed the structure of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), which provides a significant offset to Medicaid drug spending, to lift current caps on rebate amounts. Under current law, manufacturers who want their drugs covered by Medicaid must enter a federal rebate agreement under which they rebate a specified portion of the Medicaid payment for the drug to the states, who in turn share the rebates with the federal government. The rebate amount is set by statute and includes two main components: a rebate based on a percentage of average manufacturer price (AMP) and an inflationary component to account for price increases. Because of the inflationary component, the calculated rebate on a drug whose price increases quickly over time could be greater than the AMP for that drug. However, the total rebate amount has been capped at 100% of AMP since 2010. As a result, manufacturers who hit the rebate cap do not face additional Medicaid rebates if they continue to increase list price. Proposals to modify the rebate cap have included raising it to a higher amount (e.g., 125% AMP) or eliminating it entirely and have had bipartisan support. As part of the American Rescue Plan Act enacted in March 2021, the 100% of AMP limit on Medicaid drug rebates will be eliminated starting January 1, 2024.

Estimating Federal Cost Savings

Eliminating the rebate cap is expected to reduce federal spending by more than $17 billion over ten years, an estimate that has been largely consistent over various versions of proposals related to the rebate cap. The CBO score of the provision to eliminate the rebate cap estimates a reduction in federal Medicaid spending of $14.5 billion over the 2021-2030 period and $17.3 billion over the 2021-2031 period. This estimate is based in CBO’s analysis that the rebate cap led to $3 billion in lost federal and state rebates in 2019 and translates to an approximately 5-8% drop1 in federal Medicaid prescription drug spending over 2021-2031 (states would also save, as statutory rebates are split between states and the federal government). This estimate is largely in line with other cost estimates related to the rebate cap. MACPAC’s review of estimated cost savings from changes to the rebate cap indicates that cost estimates for eliminating the rebate cap save between $15-20 billion in federal spending over 10 years and indicates that raising, versus eliminating, the cap would produce “about half as much savings.”

Estimates of savings under changes to the rebate cap are, to a large extent, based on analysis of how many and which drugs currently hit the rebate cap, information that is currently proprietary. The CBO generates its cost estimate based in part on data on actual AMPs and rebates collected through Medicaid. Such data is currently not publicly available, making it difficult to replicate or extend this analysis. Thus, it is difficult to predict which drugs or manufacturers will be most affected by the policy change. In an analysis of drug rebate data from 2015, MACPAC analysis (which found annual foregone rebates on par with the CBO estimate)2 found that about 18.5% of brand drugs (at the national drug code level) reached the rebate cap in that quarter. An analysis of 2017 data found a similar share of drugs potentially affected by the rebate cap (16%) and showed that, among the drugs analyzed, the distribution of potential effects was skewed: in that analysis, 85% of reduced rebates due to the cap were attributable to 25 drugs, most of which were for diabetes treatment. That analysis also showed that one insulin drug alone accounted for 38% of lost rebates and that foregone rebates were concentrated among a few manufacturers. Recent KFF analysis finds that insulin utilization in Medicaid is still largely concentrated among brand-name drugs. It also finds that gross (pre-rebate) Medicaid spending per insulin unit on diabetes drugs declined slightly from 2017-2019, though it is unclear whether this trend means diabetes drugs still account for most foregone rebates due to the cap (as it could mean that fewer drugs are increasing prices and hitting the cap or that prices have stabilized).3

Other analysis concludes that drugs with steep price increases are most likely to be subject to the cap, since once those drugs hit the cap, they face no additional inflationary rebates under Medicaid but could gain revenue from other payers. KFF analysis of gross prescription drug spending in Medicaid finds that more than a third (34%) of drugs had price increases above inflation between 2015 and 2019,4 though not all these drugs hit the rebate cap. Drugs with fewer drugs in their drug class were more likely to have increases above inflation.5 While some analyses show Medicaid spending on specialty and biologic drugs has increased faster than non-specialty or “traditional” drugs, due at least in part to increases in the cost per claim, some of this may reflect changes in the composition of “specialty drugs” over time. Other analysis found that rebates were, on average, lower for specialty drugs compared to non-specialty drugs in Medicaid (60% versus 86%), due to both lower base rebates and lower inflationary rebates, indicating that specialty drugs may be less likely to hit the cap. Thus, it may be traditional drugs with large price increases and large rebates that are most likely to be hitting the cap. In analysis of gross spending per prescription, for example, we find that some of the largest price increases were in common classes such as antibiotics, antiemetics, sympathomimetic agents, and analgesics.

Cost savings under changes to the rebate cap also will be dependent on manufacturer responses to the change in policy. CBO indicates that actual federal savings under the current proposal to eliminate the rebate cap are subject to error due to difficulty in “forecasting future growth in drug prices and how drug manufacturers would change their pricing strategies if the cap on rebates were eliminated.” Manufacturers maintain that policies to increase Medicaid rebates create incentives to raise prices and may shift costs to other payers.6 In discussing potential outcomes under changes to the rebate cap, MACPAC explains that manufacturers could respond to the policy change by increasing launch prices for drugs or, far less likely, exiting the Medicaid program altogether. Other possible manufacturer responses could include shifting prices from brand-name to generic drugs, as there is more “room” below the current cap for generic drugs due to a lower minimum rebate (13% of AMP). Another possible challenge is potential increased gaming to inappropriately reduce reported AMP (or also best price) to reduce rebate liability once the AMP cap is eliminated. The rebate calculations rely on the pricing information reported by manufacturers; misclassified drugs or inaccurate price information in these files affects the rebate calculation. Further changes to Medicaid best price reporting in a final rule released in December 2020 may also create opportunities for gaming, but those provisions have now been delayed for six months by the Biden administration. On the other hand, it is possible that manufacturers may make no changes to their drug pricing if the additional Medicaid rebate paid is offset by increased revenue from other payers.

2. Limit or Prohibit PBM Spread Pricing in Medicaid

Federal legislation could limit or prohibit “spread pricing” in Medicaid by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) by requiring “pass through” pricing that limits PBM fees. States and MCOs are increasingly utilizing pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) in their Medicaid prescription drug programs. The financial responsibilities PBMs take on, including negotiating prescription drug rebates with manufacturers and dispensing fees with pharmacies, have generated considerable policy debate about price transparency and spread pricing. Spread pricing refers to the difference between the payment the PBM receives from the state or MCO and the reimbursement amount it pays to the pharmacy. Proposals to limit spread pricing may require “pass through pricing,” under which PBMs can retain only a “reasonable” administrative fee. Some states have limited spread pricing by eliminating the use of PBMs or requiring pass through pricing, but federal action could make this policy uniform nationally. A bill introduced in the 117th Congress would effectively prohibit spread pricing in both Medicaid managed care and Medicaid fee-for-service. Under the proposal, PBMs would be required to pass through actual pharmacy costs (net of rebates) to managed care plans or the state, charge only the actual cost of the drug plus a dispensing fee, and be provided only a reasonable administrative fee. Other potential federal policies in this area, including transparency or contractual requirements that could reduce spread pricing, are more limited than proposals to ban spread pricing outright.

Estimating Federal Cost Savings

Estimates of a federal proposal to eliminate spread pricing predict that it would lead to approximately $900 million in federal savings over 10 years, while some state analyses indicate higher degrees of spread pricing. A March 2020 CBO estimate of the federal proposal to require pass through pricing finds the spread pricing provision would produce federal savings of $929 million over 10 years, which translates to a less than 1% drop in federal Medicaid prescription drug spending. It is unclear what analysis or assumptions went into these estimates, but they are highly dependent on assumptions or understanding of the extent to which spread pricing currently exists in Medicaid. Several state reports have found relatively higher Medicaid costs due to spread pricing. For example, a 2018 report by Ohio’s state auditor found that PBMs cost the Medicaid program nearly $225 million through spread pricing in managed care. Similar analysis by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission found that PBMs charged MassHealth MCOs more than the acquisition price for generic drugs in 95% of the analyzed pharmaceuticals in the last quarter of 2018. Michigan found that PBMs had collected spread of more than 30% on generic drugs and a report found that Medicaid had been overcharged $64 million. These state estimates clearly range widely, but existing state estimates are generally higher than the average $1.9 million a year per state that the CBO estimate impliesIt is possible that state analyses occurred in states in which this issue is more problematic or that CBO’s estimates assume state activity to curb spread pricing has already addressed some of these costs.

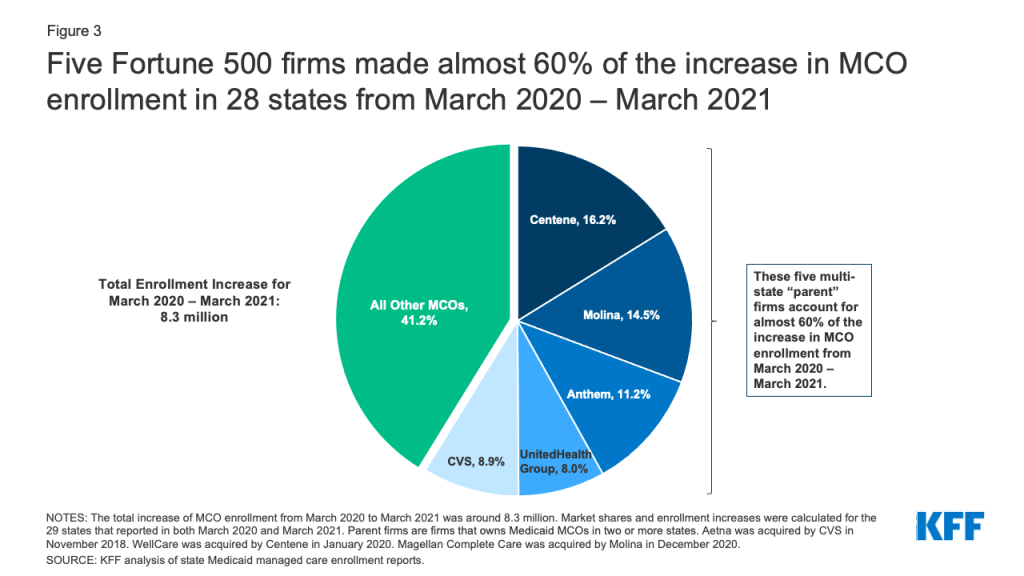

The inclusion or exclusion of fee-for-service prescription drug spending may affect the scale of potential savings from spread pricing limits. The large majority of states that use comprehensive managed care to deliver services to Medicaid enrollees generally include prescription drugs in those contracts, though many MCO states carve out certain drugs or entire drug classes and, in recent years, a growing number of states are making or considering pharmacy carve outs (likely in an effort to negotiate higher supplemental rebates). In 2019, nearly two-thirds (64%) of gross Medicaid prescription drug spending was through MCOs.7

MCOs have been the primary target of efforts to curb spread pricing, as MCOs are not bound by the same rules regarding ingredient cost reimbursement that prescription drug payments through Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) are subject to. However, current spread pricing proposals would apply to fee-for-service in addition to managed care, to the extent that states are using PBMs or PBM-like entities to administer their FFS pharmacy benefit. It is unclear to what extent including FFS in spread pricing bans increases savings. One analysis that examined “markup” in Medicaid generic drug prescriptions—defined in that analysis as the difference between gross reimbursement and acquisition cost, the benchmark used to determine Medicaid reimbursement for ingredient costs— found that in Q2 2020 approximately 7.5% of prescriptions in FFS had “high markup,” or gross reimbursement at least $15 above NADAC. However, it is not necessarily the case that those price differences reflect PBM spread (versus, for example, dispensing fees which are often $10-$15).

To the extent that spread pricing policies lead states to make different decisions about delivering pharmacy benefits through managed care, the policy could have downstream spending effects. For example, additional carve-ins could lead to different utilization control policies and thus different spending, though many states currently align those policies across FFS and MCOs.

Federal savings tied to a specific proposal are, in part, dependent on whether additional states take action to curb spread pricing. Increased state action to limit or prohibit spread pricing would likely decrease the level of federal savings estimated under a national ban on spread pricing, though—because Medicaid prescription drug costs are shared by states and the federal government— ultimately the federal government does share in cost savings due to state action in this area. State actions that focus on increasing transparency around PBM pricing could enable more precise estimates of federal savings. As of July 2019, at least 15 states had prohibited spread pricing or planned to prohibit spread pricing in 2020 and other states have placed additional transparency requirements on PBMs.

3. Eliminate or Modify Medicaid Best Price

Federal action could ease rules on Medicaid “best price,” either as part of other changes to the rebate formula or to facilitate value-based payment arrangements. The statutory formula for Medicaid rebates includes a “best price” component that ensures that Medicaid receives the lowest price offered by a manufacturer. 8 Best price is defined as the lowest available price to any wholesaler, retailer, or provider, excluding certain government programs, such as the health program for veterans. The best price benchmark is especially important for Medicaid, as brand drugs comprise a large share of spending and their rebates are often larger than the minimum rebate amount. However, the Medicaid best price provision is often cited by manufacturers and other stakeholders as a barrier to discounts and value-based contracts for other payers, since those same discounts would apply to Medicaid as well. Recent policy proposals to modify best price are largely aimed to provide exceptions for other payers. These include allowing exceptions for value-based arrangements, entirely eliminating the best price provision (which may be offset by an increase in the minimum rebate amount), and setting uniform reporting rules for prices under value-based arrangements. In late December 2020, the Trump Administration issued a final rule that allows manufacturers to report multiple “best prices” if they participate in certain types of value-based payment arrangements and allows flexibility in how manufacturers calculate which drugs apply to the VBP and the length of time to revise initial best price reports. The Biden Administration recently released a proposed rule to delay implementation of the best price changes for six months, to July 2022.

Estimating Federal Costs

Rough estimates indicate that best price leads to substantial discounts in federal and state Medicaid prescription drug spending. In the final rule, CMS assumes close to no spending impact from changes to best price and small savings due to uptake of VBP arrangements. Specifically, the agency estimated an upper and lower range of combined federal and state savings between $0 and $228 million over 5 years for provisions that make best price reporting changes to facilitate more widespread adoption of subscription or VBP arrangements in the commercial sector. CMS notes that the savings will likely be on the lower end of estimates (that is, close to zero) unless there is a significant increase in the number of states participating in the agreements. However, policies to eliminate or alter best price have the potential to generate large costs to Medicaid. Recent analysis from the CBO indicates that the average Medicaid rebate for select9 brand-name drugs was 77% of retail price in 2017, with about half of that due to the base rebate and half due to inflationary rebates. This finding means the average base rebate was approximately 38.5%, more than 15 percentage points higher than the minimum rebate amount of 23.1%. In that year, Medicaid gross spending on brand-name prescription drugs was $50 billion. Applying an approach used in earlier analysis10 , we calculate that best price led to approximately $7.7 billion in discounts (shared by the federal government and states) above the minimum rebate amount in 2017.

Using another approach, CBO also shows that best price was 59% of AMP, on average for select brand-name drugs. Using the average AMP ($509) and best price ($298) amounts included in the CBO analysis, best price leads, on average, to an addition $94 rebate per brand name prescription, about an 80% increase over the base rebate amount.11

The ultimate cost impact of changes to Medicaid best price depends on how the policy is enacted and to what drugs it applies. The range of policy options regarding best prices makes it difficult to assess a cost effect, as proposals could include an offset to easing best price such as increasing rebates. Under the specific policy issued in December 2020, of which portions are currently under review, the actual cost to Medicaid will depend on which drugs are included in VBP arrangements. The limited number of VBP arrangements under way to date have largely targeted costly “specialty drugs” with exceptionally high costs or with high costs plus relatively high demand. Using the approach above to calculate discounts due to best price for all prescription drugs, CBO indicates that base rebates for “high-priced drugs” in Medicaid were 29%, lower than those overall for brand-name drugs. KFF analysis12 finds that gross Medicaid spending for the 50 most expensive drugs (ranked by spending per prescription) was $1.4B in 2019, leading to an estimate that best price leads to $85 million per year in discounts for these drugs. Limiting the analysis to the top 10 most costly drugs, the estimate drops to $25 million. These calculations provide illustrative ranges of the scale of costs if best price is no longer available for these very high cost drugs.

The cost of changing rules for best price also depends in part on the extent to which reporting may introduce errors or allow for gaming by manufacturers. Because Medicaid rebate calculations rely on pricing information reported by manufacturers, inaccurate price information affects the rebate calculation and may reduce rebates and increase net spending. Particularly for policies that allow manufacturers to report more than one best price or choose which best price to report, it is possible that the policy will create substantial opportunities for manufacturer gaming and weaken compliance overall with the best price requirement; this gaming could further raise federal and state Medicaid costs. While manufacturers will still be required to report best prices outside of VBP arrangements under the December 2020 regulations, nothing prohibits them from shifting certain drugs entirely to VBP arrangements, which would only offer discounts to states that participate in those arrangements. It is unclear to what extent manufacturer behavior may affect ultimate costs or savings under the rule.

Federal savings are also dependent on which rebates and discounts are included in the best price calculation. There is uncertainty over the extent to which manufacturers already include PBM rebates in best price, the relative importance of those manufacturers to Medicaid drug spending and rebates, and how much their PBM rebates would affect how best price is calculated, relative to discounts that currently are incorporated into best price. There are no cost estimates on an explicit requirement that commercial PBM rebates be included in best price calculations by manufacturers. According to the HHS Office of Inspector General, there is a wide range of assumptions taken by manufacturers: most include some PBM rebates, some include all and some do not include any PBM rebates. Those that do not include PBM rebates claim that the PBM rebates are not reflected in retail prices faced by consumers. An explicit requirement likely may not produce “scoreable” savings on the assumption that many of the PBM rebates are already included in best price under current law.

4. Increase Minimum Rebate Amount for Certain Drugs

Federal action could aim to increase the minimum Medicaid rebate amount based on launch price or other factors that define a high-cost drug. The Medicaid rebate amount is set is statute based on a formula that sets the rebate at a minimum amount (for brand name drugs, the greater of 23.1% of AMP or the difference between AMP and best price; for generic drugs, 13% of AMP). As discussed above, the MDRP also includes a penalty for price increases above inflation, capped at 100% AMP until 2024, to address the issue of increasing drug prices over time. However, manufacturers producing new drugs may set their launch prices high in an effort to capture greater net reimbursement. For example, in its estimate of the effect of minimum rebate increases passed under the ACA, CBO predicted that manufacturers would increase launch prices by about 4% and that supplemental rebates would decrease. Subsequent research has had mixed findings on how the increase in base rebate led to other pricing responses, and specific Medicaid rebate proposals could target other aspects of pricing such as launch price. One potential federal legislative action to combat this response is an increase in the statutory (federal) minimum rebate, with a sliding scale based on launch price or another factor that defines a high-cost drug, to deter high launch prices for new drugs or simply increase minimum rebates on high-cost drugs. For example, MACPAC recently considered changes to the rebate formula for specific categories of high-cost drugs, including drugs approved through the FDA’s accelerated approval process, and the Commission adopted a recommendation that Congress increase the base minimum rebate on drugs approved through the accelerated-approval pathway with an additional inflationary rebate for drugs that have not completed confirmatory trials in a specified number of years.

Estimating Federal Cost Savings

Federal savings due to proposals to link rebates to launch prices or increase minimum rebate amounts for specific drugs are highly dependent on the specific proposal or drugs targeted, but estimates of current proposals indicate federal savings may be relatively small. CBO scored the MACPAC proposal to increase the base rebate for accelerated approval drugs by 10 percentage points, with a 20 percentage point increase in the inflationary rebate if the manufacturer has not completed confirmatory trials within five years, at federal savings up to $50 million in the first year and up to $1 billion over the first five years. That estimate is largely in line with other calculations that, while the policy could lead to substantial savings on a given specific, high-cost drug accelerated approval drugs account for a very small share of overall Medicaid spending.

Broadening rebate increases to target other groups of specialty drugs could substantially increase federal savings. For example, increasing the minimum rebate amount for specialty drugs by 10 percentage points (to 33.1% AMP) could increase rebates paid for specialty brand-name drugs from the current average base rebate for these drugs (29%) by 4 percentage points. Previous analysis indicates that specialty drugs account for 35% of total net Medicaid expenditures. If all these drugs were affected by the increase, it could lead to approximately $900 million more in statutory rebates (shared by states and the federal government).13 It is unclear how such a policy would be applied, as there is no uniform definition or classification of “specialty” drug. If the policy targeted only very high-cost drugs, such as the top 50 most costly drugs, savings would be lower: an additional 4 percentage point rebate on gross spending of $1.4 billion for these drugs translates to approximately $57 million. The increased rebates would be shared by the federal and state governments, so federal savings would be lower. In addition, some of the upfront savings from the increase in the minimum rebate would be offset by lower reductions in net spending due to best price discounts, supplemental rebates and inflation-related rebates that would otherwise ramp up over time for such drugs.

Further expanding policies to increase minimum rebates to target drugs with high launch prices could lead to substantial short-term savings, though long-term effects are uncertain. Analysis of drug prices has indicated that, while year-to-year prices increases have slowed in recent years, launch prices have increased substantially: between 2006 and 2018, it found that median launch cost per month of treatment for brand-name drugs increased 934%; while launch prices dropped in 2019, the analysis still found a 381% increase in median launch prices between 2006 and 2019. The analysis showed increases on a similar scale for launch prices for generic drugs. KFF analysis of Medicaid rebate data shows that the average gross spending per prescription for drugs new to the MDRP from 2011 to 2018 was more than 2700% higher for brands and 468% higher for generics than that for other drugs in the class.14 Median price differences were smaller (less than 300% for brands and 24% for generics), indicating that some very high-priced new drugs drive these differences. Some of these “new” drugs may have been new packaging or reformulations of existing drugs, which would lead to an underestimate of launch prices of new drugs. Altogether, gross Medicaid spending for the most costly (top 10%) of new drugs in Medicaid averaged more than $4 billion per year from 2015-2018. Medicaid is most likely obtaining rebates for these drugs similar to those for “high priced drugs,” which CBO reports are 29% or just above the base rebate, compared to an average rebate for high-priced drugs of 53%. Thus, increasing the base rebate for costly new drugs in their first year could lead to federal and state savings.

There are major unknown factors in predicting costs or savings of policies targeted at launch prices or targeted to specific high-cost drugs, including when specific products will come to market and the extent to which Medicaid rebate policy drives overall market prices. Recent analysis of the implications of the drug pipeline for Medicaid indicates that there are multiple, very high-cost drugs coming to market that could lead to substantial drug spending within Medicaid, though it is unclear exactly when these drugs will be on the market and prescribed. State Medicaid programs could impost utilization control measures on these drugs, which would further limit costs. In addition, Medicaid’s ability to drive market prices such as launch price through changes to MDRP may be limited. Other analyses have noted that, while there is some evidence that Medicaid policy influences prices to other payers, manufacturers pricing decisions also are driven by a range of factors besides Medicaid reimbursement, including competition, coverage decisions by other payers, and long-term profit calculations. Research from other countries has also shown that negotiating launch prices does not necessarily lead to lower launch prices.

5. Allow Importation of Prescription Drugs

Some federal proposals allow buyers, including state Medicaid programs, to import drugs from foreign markets to access lower prices generally available in other countries. Federal law already allows pharmacists and wholesalers to import prescription drugs directly from Canada, subject to specified limitations and safeguards. Some importation proposals focus on allowing additional actors, such as states and other entities (including consumers) to import drugs, while others would allow importation from additional countries. In fall 2020, the Trump Administration issued a final rule and FDA guidance for industry creating new pathways for the importation of drugs from Canada and other countries by pharmacists, wholesales, states, and certain entities, subject to specified limitations and safeguards. The law requires importation to result in a significant reduction in drug costs and requires states to submit a plan for approval to the FDA. While some states have developed importation proposals, few have moved forward with implementation due to barriers related to regulation, safety and overall financial impact. While Biden supported importation during the Presidential campaign, it is unclear if the Biden Administration will approve any state plans to move forward with implementation of an importation proposal. In a recent court filing, the Biden Administration indicated that implementation and approval of state plans for importation would be difficult and that Canada would oppose such efforts.

Estimating Federal Cost Savings

While importation proposals are estimated to generate federal savings, the savings generated on behalf of Medicaid are likely small. Federal programs, which use mechanisms such as the best price provision in Medicaid and the federal supply schedule, already pay among the lowest prices in the market. CBO scored the impact of broad importation policies in a 2003 importation bill, which would have allowed pharmacists, wholesalers and individuals to import drugs from 25 countries, and estimated estimated small reductions in spending by federal programs—just $2.9 billion across Medicaid, FEHB, TriCare, and Medicare over the 2004-2013 period. Though current proposals are more limited in scope, the landscape has changed substantially since the 2003 bill, which came before the creation of Medicare Part D (which increased federal subsidy of prescription drugs) as well as changes to Medicaid drug rebates that have increased the amount of rebates paid to states and the federal government. A more recent CBO score estimates federal savings of importation legislation at $6.8 billion over ten years, but does not specify savings by program. In its final rule, the FDA did not provide estimates of importation savings due to significant uncertainty around the number of participants in the importation program as well as eligible drugs and their relative prices, but noted savings would likely be less than other, more broad proposals.

States that have developed importation plans have also developed cost savings estimates for their proposals and show limited Medicaid savings. Vermont’s report concluded that importation would not generate significant savings for the Medicaid program, largely due to the state’s rebate agreements. Florida’s report on drug importation found notable savings under importation, but the analysis removed drugs that were already deeply discounted in Medicaid and would not yield any greater savings or were ineligible for inclusion due to other restrictions. Thus, it is not clear to what extent savings would accrue to Medicaid. Medicaid wholesalers and pharmacists are included as eligible importers in Florida’s importation law but would likely only import drugs that did not receive significant Medicaid rebates.

Key factors affecting estimates related to importation include whether Medicaid rebate rules apply to imported drugs as well as how imported drugs feed into Medicaid price benchmarks. Due to the high rebate amounts Medicaid receives, unless states could claim rebates on top of lower imported prices, imported prices would likely not be lower than net Medicaid prices. However, CMS guidance on the recent FDA final rule states that drugs imported from Canada under this rule are not eligible for rebates and would not be reported for best price. Importation also has implications for pharmacy reimbursement. Medicaid does not pay manufacturers directly for drugs but rather reimburses pharmacies for their acquisition costs. If importation lowers acquisition costs (which is the goal of such policies), pharmacy rates would need to be adjusted to account for those lower acquisition costs for Medicaid to realize lower prices but the mechanism for tracking and reporting dispensing of imported drugs is unclear. The number of states that take up the option to import drugs as well as the specific drugs imported also would have significant implications for any cost savings.

Looking Ahead

Recently introduced legislation targets prescription drug prices for both Medicaid and other payers and includes several of the policy proposals analyzed here, and it is possible that additional policy proposals or legislation will be introduced. In addition, states are taking a range of actions in Medicaid prescription drug policy, some of which directly interact with federal proposals and their likely costs. Prescription drug spending growth remains an area of concern for states, particularly payment for new, high cost therapies, and states may continue to adopt new policies in the absence of federal action. Understanding the cost and savings implications of policies currently under discussion, as well as the factors driving those estimates or uncertainty in them, can help policymakers and others assess the relative impact of policy options.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. We value our funders. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

We are grateful to Edwin Park and Rena Conti for their input into the policy options included and considerations for estimating or understanding their potential costs.