The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

Who are the Unvaccinated?

As of late May 2021, a majority of U.S. adults have received a COVID-19 vaccine, with 62% of adults reporting having gotten at least one dose according to the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor. There are still substantial shares of the adult population who have not received a vaccine and many do not plan on getting vaccinated. This analysis, drawing on data from the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor, provides some insights into the demographics of the currently unvaccinated population as well as their views of vaccines generally and the pandemic more broadly.

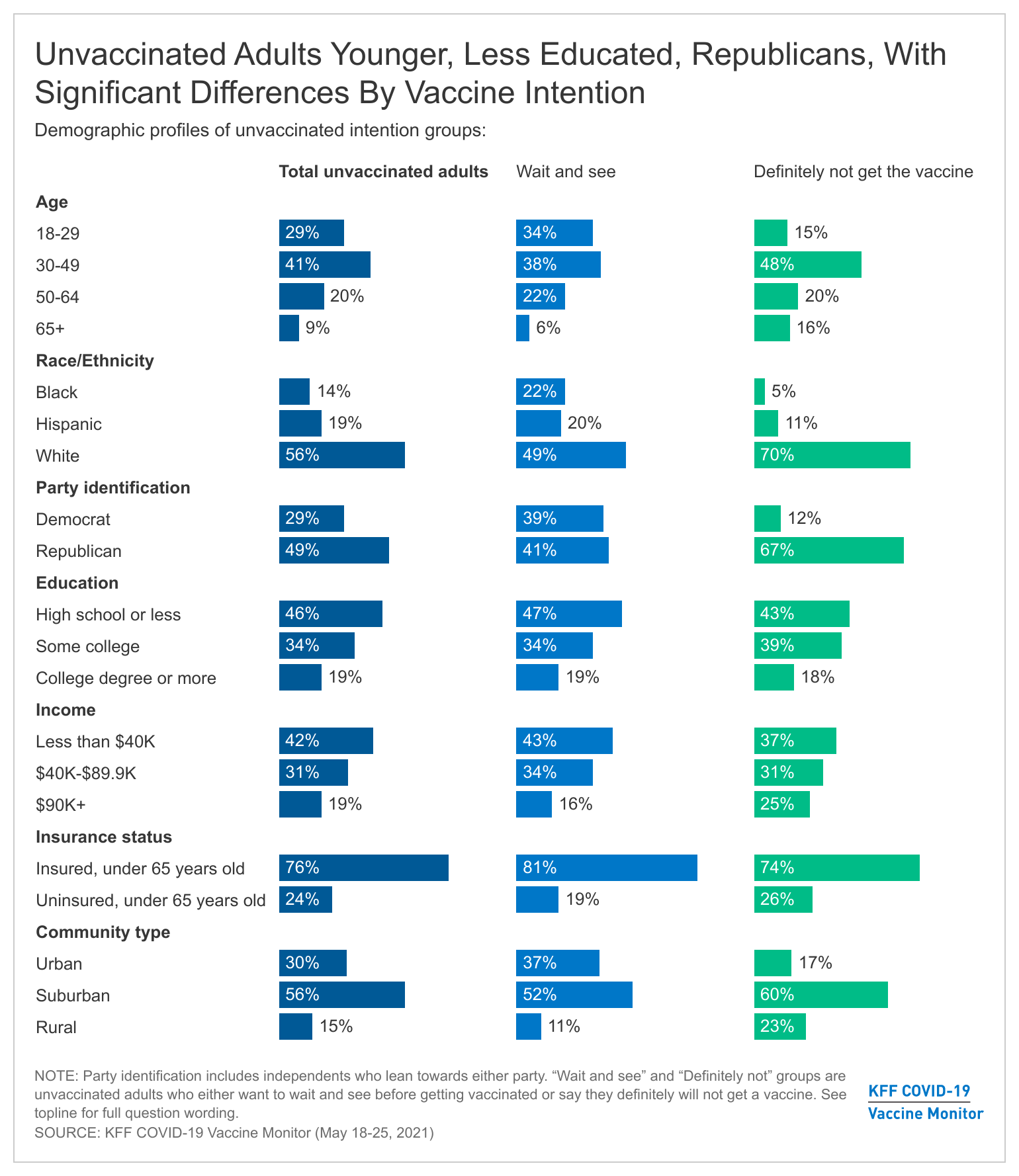

Unvaccinated adults are a shrinking population in the U.S. that, as of late May 2021, consists of about one-third of U.S. adults (37%). Adults in this group are those, who despite outreach efforts and being eligible for a vaccine for at least six weeks, have not received a COVID-19 vaccine. The unvaccinated group are younger, more likely to identify as Republicans or be Republican-leaning, and more likely to have lower levels of education and lower incomes than the vaccinated population.

Unvaccinated adults are significantly younger, with 29% of those in the group falling in the 18-29 year old range compared to 17% of those in the vaccinated group. In addition, a smaller share of unvaccinated adults are 65 and older (9%) than the vaccinated group (28%). This may reflect recent changes in access to vaccines with older populations being among the first groups eligible to be vaccinated in states. President Biden announced that 90% of adults would be eligible to get the vaccine by April 19th but there were still significant waiting times for many adults who had just gotten eligible. Over the next few weeks we will better know whether these age differences are due to vaccine access or to actual different vaccine intentions among younger adults.

There are strong partisan differences in vaccine intentions with almost half (49%) of unvaccinated adults identifying as Republicans or Republican-leaning independents, compared to three in ten (31%) vaccinated adults. On the other hand, Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents make up a majority of the vaccinated population (about six in ten), while about three in ten in the unvaccinated population identify as Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents.

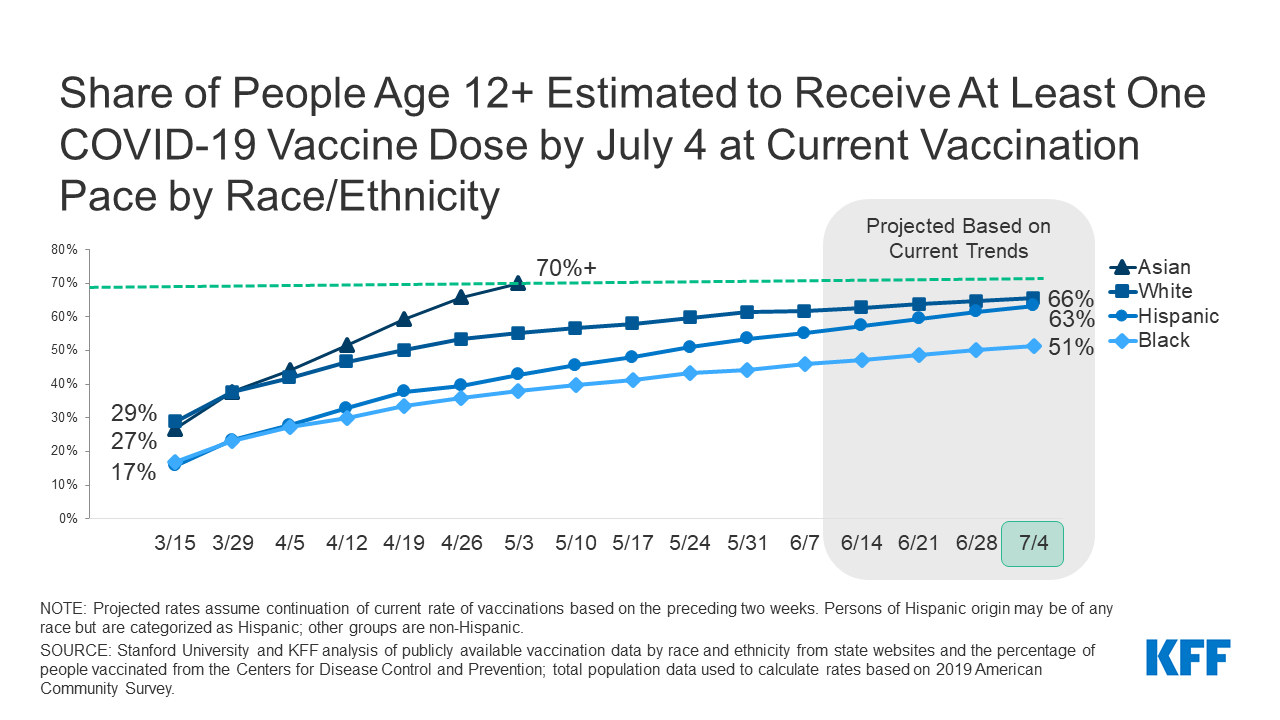

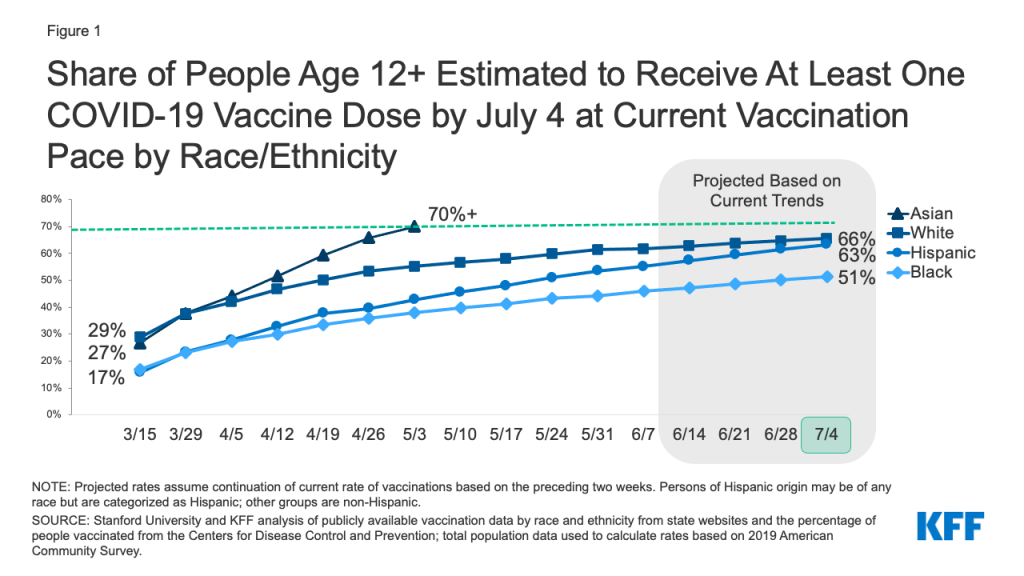

Compared to vaccinated adults, smaller shares of White adults are unvaccinated, with no significant differences for Black and Hispanic adults on whether they have received at least one-dose so far, despite Black and Hispanic adults lagging in vaccination rates compared to Whites. Around two-thirds (64%) of vaccinated adults are White, compared to 56% of unvaccinated adults. With difficulty accessing vaccine locations and services disproportionately impacting the non-White population, current outreach continues to strive to bridge the gap.

Americans with lower levels of education make up a larger share of the unvaccinated population than the vaccinated one, with 46% of unvaccinated adults holding a high school degree or less compared to 34% of vaccinated adults. Vaccinated Americans are twice as likely as unvaccinated to have a college degree or higher (38% vs. 19%).

The unvaccinated group also tends to include disproportionate shares of adults without health insurance coverage as well as those with lower levels of income. Those under the age of 65 without insurance make up about one quarter of the unvaccinated population, and 42% of all unvaccinated adults report earning less than $40K a year.

The “Definitely not” group compared to the “Wait and see” group

KFF has been tracking vaccine intentions over the past six months and while there are clear demographic differences between vaccinated adults and unvaccinated adults, there are also differences within the unvaccinated population depending on whether they are still open to getting a vaccine or not. Specifically, those who say they want to “wait until it has been available for a while to see how it is working for other people” before getting vaccinated, the wait and see group (12% of all adults) look distinctly different from the most vaccine resistant group, those who say they will “definitely not” get a COVID-19 vaccine (the definitely not group represents about 13% of U.S. adults). While the share of the U.S. adult population who self-identified as “wait and see” has decreased over the past several months as tens of millions of U.S. adults have received a vaccine and few people have experienced serious side effects from the vaccine, the share of the public who are in the “definitely not” group has not shifted dramatically over the past six months.

The key demographic differences between the “wait and see” and the “definitely not” groups center on racial and ethnic identity and political partisanship. Half of those in the “wait and see” group are people of color. Throughout the rollout of the vaccines, larger shares of Black and Hispanic adults have reported they would want to “wait until it has been available for a while to see how it is working for other people” before getting vaccinated. This still holds true in the latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor with Black adults and Hispanic adults both representing about one-fifth of the “wait and see” group. On the other hand, the most vaccine resistant group, those who say they will “definitely not” get a COVID-19 vaccine is overwhelmingly made up of White adults (70% of the group compared to 49% of the “wait and see” group).

The “wait and see” group is also split politically, with about four in ten who identify as Republicans or Republican-leaning independents and another four in ten as Democrats or Democratic-leaning, while the more vaccine resistant “definitely not” group is overwhelmingly Republican-leaning, with two-thirds (67%) in the group identifying as either Republican or Republican-leaning independents.

There is a smaller share of rural residents in the “wait and see” group (11%) than in the “definitely not” group (23%) but the “definitely not” group is also characterized by other demographics that disproportionately live in rural areas, including more White adults and Republicans.

There are no significant differences when you look at age, education, and insurance status among those who are unvaccinated with about seven in ten in both unvaccinated groups under the age of 50, about one in five have college degrees, and similar shares reporting being uninsured.

Vaccine Intentions Among Unvaccinated Adults Strongly Connected To Views Of Pandemic, Past Flu Vaccine Behavior

People’s intentions to get a COVID-19 vaccine are also largely connected with their previous experience with vaccines and their overall views of the pandemic.

Unvaccinated adults are less likely to reporting getting of the flu vaccine, with over three-quarters (77%) saying they do not normally get a flu vaccine each year. The vast majority of unvaccinated adults who say they will “definitely not” get the COVID-19 vaccine say they don’t regularly get their flu vaccine (91%), compared to about seven in ten (71%) of those in the “wait and see” group.

About six in ten unvaccinated adults (57%) think that what is said about COVID-19 in the news is generally exaggerated, significantly larger than the share of vaccinated adults who say the same (22%). Again, differences exist between the “wait and see” and the “definitely not” with close to twice as many of the latter group saying the news has exaggerated Covid-19. About three-fourths of vaccinated adults either say the news have either been “generally correct” or “generally underestimated” the severity of the pandemic.

In addition to thinking the news has overstated the problem, most unvaccinated adults say they are not worried about getting sick from coronavirus. About seven in ten unvaccinated adults overall, including nearly nine in ten (88%) of those in the “definitely not” group say they are either “not too worried” or “not at all worried” about personally getting sick from COVID-19. Those in the “wait and see” group are more likely to say they are worried, but still a majority of them (56%) say they are not worried.

Despite being less likely to be worried about getting sick, one-third of unvaccinated adults say they know someone close who has died due to COVID-19, according to the April COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor – including 29% of those who say they definitely won’t get the vaccine.

Unvaccinated Adults Have Different Concerns and Some In The “Wait and See” Group Say Certain Incentives Could Persuade Them

The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor has consistently found that many unvaccinated adults report being concerned about the safety of the vaccines. This is true among both the “wait and see” group and the “definitely not” group with large majorities of both saying they are concerned the vaccines are not as safe as they are said to be. The two groups differ on other concerns. For example, they differ in terms of concerns about the vaccine’s impact on fertility (two-thirds of the “definitely not” group say they are at least somewhat concerned about this compared to 44% of the “wait and see” group) and on concerns about having to pay for a vaccine (one-third of the “wait and see” group is concerned about this compared to 19% of the “definitely not” group). Nearly four in ten (37%) in the “wait and see” group also express concern about being able to get the vaccine from a place they trust, perhaps another indicator of health care access issues within this group.

Many states, public health departments, and employers are working on incentives aimed at increasing vaccine uptake among the currently unvaccinated populations. KFF has been tracking the reported effectiveness of various potential incentives for the past few months and finds substantial shares of those in the “wait and see” group say they would be more likely to get the vaccine if it was offered to them at a place they normally go for care (46%), they were required to get vaccinated in order to fly on an airplane (41%) or attend large gatherings (40%). In addition, nearly half of the “wait and see” group (44%) say they would be “more likely” to get a vaccine if one of the vaccines currently authorized for emergency use received full approval from the FDA. Yet, few of those in the “definitely not” group say any of these incentives, conveniences, or requirements would make them more likely to get vaccinated. This is also consistent with previous reports that finds these two groups differ in terms of reported access, information needs, and influence of both “carrot” and “stick” methods of incentives to get vaccinated.

It is clear there are distinct groups within the unvaccinated population and their views are not monolithic. While some within the “wait and see” population may be persuaded to get a vaccine in the coming weeks, few in the “definitely not” group show any indication of changing their minds as their views towards the COVID-19 vaccine are consistent with past vaccine behaviors as well as overall views of the threat of COVID-19.