Health and Health Care Experiences of Hispanic Adults

Findings

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a stark disproportionate toll on people of color, including the Hispanic population. These disparate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have exposed and exacerbated longstanding underlying disparities in health and health care facing Hispanic people. Prior to the pandemic, these disparities had already been compounded by immigration policies implemented during the Trump administration that increased fears among immigrant families and made some more reluctant to access programs and services, including health coverage and health care. Although the Biden administration has since reversed many of these policies, they likely continue to have lingering effects.

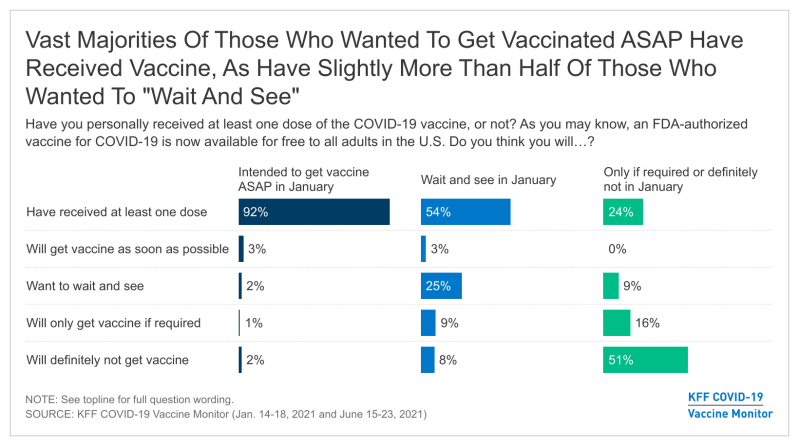

This report provides insights into the health care experiences of Hispanic adults amid the current environment and examines how they vary by key factors, including insurance and immigration status. A prior report examined the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 for Hispanic adults and their attitudes, experiences with, and barriers to getting COVID-19 vaccinations. This report from the KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is based on interviews with 778 Hispanic adults in the U.S., including 334 conducted in Spanish, 392 with adults born outside the U.S., including 185 who indicated that they do not have lawful permanent resident status (referred to in this report as “potentially undocumented”).1

Employment and Income

Individuals’ employment and income affect access to health insurance and ability to afford health care. People in lower wage jobs are less likely to be offered health insurance by their employer and may have more difficulty affording it when it is offered due to their limited incomes. Moreover, people with limited incomes may face more challenges paying for health care costs.

Although Hispanic adults are as likely as White adults to say they are employed, they are more likely to report living in a lower income household. Over half (54%) of Hispanic adults say they are employed, similar to the shares of Black (52%) and White (54%) adults (Figure 1). Among Hispanic adults, nearly six in ten (57%) potentially undocumented Hispanic adults say they are employed, similar to the shares among Hispanics who are U.S.-born (54%) and who are lawful permanent residents (50%). Employed Hispanic adults are more likely than employed White adults to say they currently work solely at a location outside their home (69% vs. 57%), contributing to increased risk of exposure amid the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for those who are unvaccinated. Among employed Hispanic adults, those who are potentially undocumented are more likely to say they are currently working outside the home—84% of potentially undocumented employed Hispanic adults say they work only outside the home compared to 60% of employed U.S.-born Hispanic adults.

Despite being as likely as White adults to report being employed, about half (52%) of Hispanic adults say their annual household income is less than $40,000 compared to 29% of White adults (Figure 2). Nearly eight in ten (78%) potentially undocumented Hispanic adults report annual household income of less than $40,000, compared to 60% of lawful permanent residents and 40% of U.S.-born Hispanic adults.

Health Coverage and Program Participation

Health insurance makes a difference in whether and when people get necessary medical care, where they get their care, and ultimately, how healthy they are. Uninsured adults are far more likely than those with insurance to postpone health care or forgo it altogether. Hispanic people have faced longstanding disparities in health coverage. They were more likely than their White counterparts to be uninsured prior to the pandemic and faced widening gaps in coverage between 2018 and 2019. These coverage declines may, in part, reflect changes to immigration policy, particularly the “public charge” policy under the Trump administration, which contributed to growing fears among immigrant families about participating in public programs, including health coverage. Although the Biden administration has since reversed many of these policies, they may continue to have lingering effects. Further, the economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have likely contributed to additional coverage losses that may further widen disparities in coverage for Hispanic people.

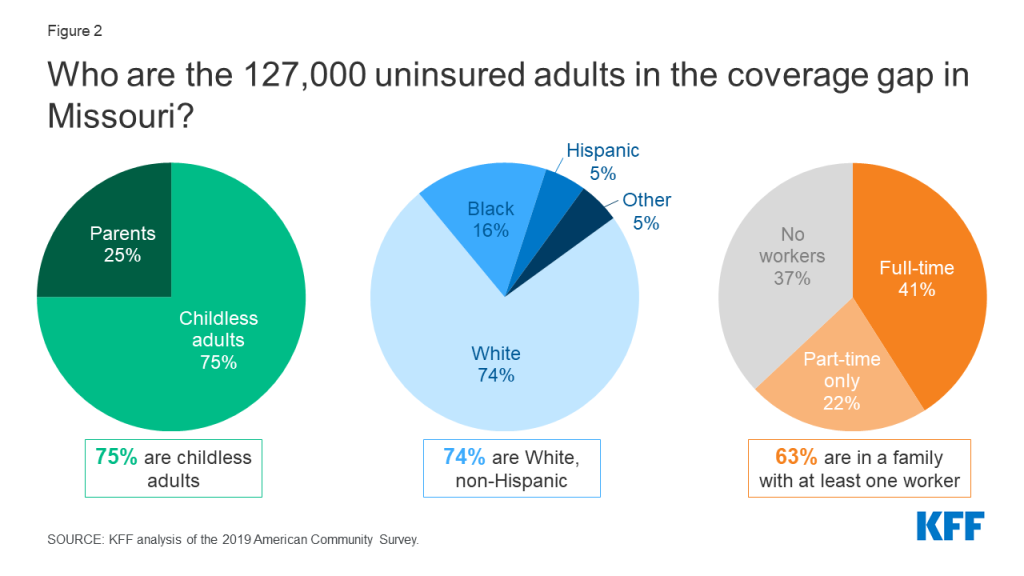

Three in ten nonelderly Hispanic adults (31%) say they are uninsured compared to 15% of Black adults and 9% of White adults (Figure 3). The share reporting they don’t have health insurance is much higher among nonelderly Hispanic adults who are potentially undocumented (71%) and somewhat higher among those who are lawful permanent residents (31%) compared to U.S.-born Hispanic adults (18%).

These patterns likely reflect more limited access to employer-sponsored coverage among foreign-born Hispanic adults, due to higher rates of employment in low-wage jobs that are less likely to offer health coverage, as well as more limited access to and barriers to enrolling in public coverage options. Lawfully present immigrants may qualify for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program, but many, including most lawful permanent residents, must wait five years after obtaining a qualified immigration status before they may enroll. Lawfully present immigrants can purchase coverage through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces and may receive subsidies for this coverage, including those who are not eligible for Medicaid or CHIP because they are in the five-year waiting period. Although lawfully present immigrants are eligible for coverage, they face a range of potential enrollment barriers, including fear, confusion about eligibility policies, difficulty navigating the enrollment process, and language and literacy challenges. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible to enroll in Medicaid or CHIP or to purchase coverage through the ACA marketplaces.

Some Hispanic adults, particularly those who are potentially undocumented, report that they have avoided seeking assistance for food, housing, and/or health care due to immigration-related fears. One in ten Hispanic adults (11%) say there was there a time in the past 3 years when they or a family member decided not to apply for or stopped participating in a government assistance program because they were afraid it might negatively affect their or a family member’s immigration status (Figure 4). Across Hispanic adults overall, 6% say they did not apply for or stopped participating a program to help with food, 4% say assistance for housing, and 3% say a health care program. The share saying they or a family member did not apply for or stopped participating in a program in the past 3 years due to immigration-related fears increased to 13% among lawful permanent residents and 26% among potentially undocumented Hispanic adults. Overall, 21% of potentially undocumented Hispanic adults say they did not apply for or stopped participating in a program to help with food, 12% say assistance for housing, and 11% say a health care program.

Access to and Experiences Obtaining Health Care

Beyond health coverage, other factors such as having a usual source for health care, accessibility of health care provider locations, and affordability of care have implications for individuals’ access to and use of care, including preventive and primary care as well as care for chronic conditions. Further, individuals’ experiences and relationships with health care providers, including patient-provider communications, can affect the quality of care they receive, their satisfaction with care, and health outcomes.

Usual Source of Care

A usual source of care is a health care provider where people usually go when they are sick or need advice about their health. Research finds that people with a usual source of care are more likely than those without a usual source to get care and less likely to have difficulty obtaining care or to go without receiving needed services.

Hispanic adults, particularly those who are potentially undocumented and uninsured, are more likely than their White counterparts to say they do not have a usual source of care other than the emergency room. Nearly one in four (24%) Hispanic adults overall report no usual source of care other than an emergency room, higher than the share of White adults (12%) and similar to the share of Black adults (28%) (Figure 5). Among Hispanic adults, roughly three in ten potentially undocumented (32%) and lawful permanent resident (29%) adults say they have no usual source of care other than the emergency room, compared to about one in five (19%) U.S.-born adults. Similarly, among nonelderly Hispanic adults, those who are uninsured are more likely than those with insurance to say they do not have a usual source of care other than the emergency room (37% vs. 20%).

Hispanic adults are also more likely than White adults to say a neighborhood clinic or health center is their usual source of care (33% vs. 16%). The shares relying on a clinic or health center as their usual source of care are even higher among lawful permanent resident (42%) and potentially undocumented (40%) Hispanic adults. In contrast, Hispanic adults are less likely than White adults to say their usual source of care is a private doctor’s office (34% vs. 64%). The share saying a clinic is their usual source of care is similar for both uninsured (36%) and insured (33%) nonelderly Hispanic adults, but those who are uninsured are less likely to say they use a private doctor’s office as their usual source of care than their insured counterparts (22% vs. 38%).

Access to and Affordability of Care

About one in five (21%) Hispanic adults say it is somewhat or very difficult to get to a location for health care versus 12% of White adults (Figure 6). The remaining nearly eight in ten Hispanic adults (78%) say it is very or somewhat easy to find health care at a location that is easy to get to, compared to 86% of White adults. Less than half of Hispanic adults say it is very easy (46%) compared to 62% of White adults. Among Hispanic adults, those who are foreign-born are less likely to say it is very easy to get to a location for health care, with 39% of lawful permanent residents and 35% of potentially undocumented adults saying it is very easy compared to 53% of those who are U.S.-born. Similarly, among nonelderly Hispanic adults, those who are uninsured are less likely to say it is very easy (34%) compared to those with health insurance (50%). Nearly three in ten uninsured Hispanic adults (28%) say it is very or somewhat difficult to find care at a location that is easy to get to.

Overall, the share of Hispanic adults who say it is very or somewhat difficult to find health care they can afford is similar to the share of White adults (37% vs. 32%) (Figure 7). However, Hispanic adults are less likely than White adults to say it is very easy to find affordable care (29% vs. 42%). Further, among nonelderly Hispanic adults, those who are uninsured are twice as likely as those with insurance to say it is very difficult to find health care they can afford (24% vs. 12%). There are no major differences in the reported ease of finding affordable care by immigration status. The reliance on community health centers as a usual source of care by a high share of Hispanic adults may mitigate potential challenges finding affordable care among Hispanic adults even though they are more likely to be uninsured and have lower incomes than White adults, since health centers provide free or low-cost care regardless of insurance status. Other data also show that Hispanic adults are less likely to utilize care than their White counterparts.2

Provider Communications and Linguistic Access to Care

Communication plays a key role in the delivery of health care and affects patient–provider relationships and the health care people receive. Studies have found that language barriers between providers and patients may result in excessive ordering of medical tests, lack of understanding of medication side effects and provider instructions, decreased use of primary care, increased use of the emergency department, and inadequate follow-up.

Some Hispanic adults, particularly those who are foreign born or uninsured, say it is difficult to find a doctor who explains things in a way that is easy to understand (Figure 8). Overall, three-quarters (74%) of Hispanic adults say it is very or somewhat easy to find a doctor who explains things in a way that is easy to understand, but nearly one-quarter (24%) say it is very or somewhat difficult, higher than the share of White adults (16%) and similar to the share of Black adults (23%). Foreign-born Hispanic adults are more likely than those born in the U.S. to say it is difficult to find a doctor who explains things in a way that is easy to understand, with 34% of potentially undocumented adults and 31% of lawful permanent resident adults saying it is somewhat or very difficult compared to 16% of those who are U.S.-born. Having a usual source of care also makes a difference in the ability to find a doctor who explains things in a way that is easy to understand, as Hispanic adults without a usual source of care are more likely to report it is somewhat or very difficult than those with one (30% vs. 21%). There are no significant differences in the share of nonelderly Hispanic adults who say it is difficult by insurance status, but those who are uninsured are less likely to say it is very or somewhat easy compared to those who are insured (65% vs 77%). Linguistic access to care is also a challenge for some Spanish-speaking adults. Among Hispanic adults who completed the survey in Spanish, one-third (33%) say it is very or somewhat difficult to find a doctor who speaks their preferred language or provides an interpreter when needed.

Experiences with Providers

Most Hispanic adults (83%) say it is very or somewhat easy to find a doctor who treats them with dignity and respect, similar to the share of White adults (84%) who say so (Figure 9). However, about one in four (24%) potentially undocumented Hispanic adults say it is somewhat or very difficult, compared to 14% of U.S. born Hispanic adults and 11% of lawful permanent residents. Among nonelderly Hispanic adults, there are no significant differences in reported ease of finding a doctor who treats them with dignity and respect by insurance status. However, among Hispanic adults overall, those without a usual source of care are more likely to say it is very/somewhat difficult compared to those with a usual source of care (20% vs. 12%).

Just over half (52%) of Hispanic adults say it is easy to find a doctor with shared background and experiences to them versus over two-thirds (67%) of White adults (Figure 10). The share who say it is very or somewhat easy to find a doctor with shared background and experiences falls to 42% among potentially undocumented Hispanic adults compared to 56% of those who are U.S. born. Similar differences are observed among Hispanic adults based on whether they have a usual source of care, with 42% of those without a usual source of care saying it is very or somewhat easy compared to 56% of those with a usual source of care. Ease of finding a doctor with the same background and experiences does not vary by insurance status among nonelderly Hispanic adults.

Implications

Overall, these findings show that, consistent with research from prior to the pandemic, Hispanic adults are more likely to be uninsured than their White counterparts. They also are less likely to have a usual source of care other than an emergency room and to rely on community health centers as their source of care. Further, they are more likely than their White counterparts to say it is difficult to get to a location for health care. The findings further show that these access challenges generally are amplified among Hispanic adults who are foreign-born and uninsured. Beyond increased barriers to accessing care, the findings also highlight some challenges communicating with providers among Hispanic adults, particularly among those who are foreign-born and those without a usual source of care. These challenges include increased difficulty finding a doctor who explains things in a way that is easy to understand, finding a doctor with shared background and experiences, and linguistic access challenges for Spanish-speaking adults.

Despite having a higher uninsured rate and being less likely to have a usual source of care, Hispanic adults are not more likely than White adults say it is difficult to find affordable care. This finding may, in part, reflect the primary role community health centers play as a source of care among Hispanic adults. Community health centers provide comprehensive primary care as well as supportive services such as health education, translation, and transportation to patients who are disproportionately low-income, people of color, uninsured, or publicly insured. They provide these services regardless of patients’ ability to pay or immigration status and charge for services on a sliding fee scale. As such, health centers facilitate access to affordable, culturally and linguistically competent care and can help mitigate challenges to accessing care. This finding may also reflect that Hispanic adults are less likely than their White counterparts to utilize care. For example, other federal survey data show that a quarter of Hispanic adults have not seen a doctor in the past year, compared to less than one in five White adults.3

The overall findings on Hispanic adults’ reported experiences and perceptions of care may reflect certain cultural norms, including an emphasis on politeness and conflict avoidance, and variations in expectations and experiences with the U.S. health care system. For example, research suggests that Hispanic people may give higher ratings to physicians and health plans despite worse health care experiences due to a cultural disposition to be deferential to those who are presumed to be of higher status. Moreover, immigrants may have lower expectations of the healthcare system based on prior experiences with health care in their countries of origin and less experience interacting with the U.S. health care system. Similarly, uninsured individuals’ reported experiences and perceptions of health care and health care system may reflect less interaction with the health care system.

Together these findings highlight the importance of addressing disparities in coverage, access to care, as well as in patient-provider communications for improving health and well-being of Hispanic adults. Further, they highlight the variation of experiences and needs within the Hispanic population which can help inform these efforts going forward. Addressing disparities in health and health care among the Hispanic population is of increasing importance given their growing share of the nation’s population and that they have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Endnotes

- The survey used questions to determine the likely immigration status of respondents by asking those who were born outside the U.S. whether they were a permanent resident (i.e. had a green card) when they came to the U.S. or if their status had been changed to permanent resident since arriving. In the current survey, 18 percent of Hispanic adults said they have not been granted permanent resident status, indicating that they are likely to be undocumented immigrants, although this group may also include a small number of temporary lawful residents. ↩︎

- KFF analysis of 2019 National Health Interview Survey Data ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎