Medicare and Dental Coverage: A Closer Look

Issue Brief

Dental benefits are not generally covered by Medicare, except under limited circumstances, and many people on Medicare do not have any dental coverage at all. Some Medicare beneficiaries have access to dental coverage through other sources, such as Medicare Advantage plans, but the scope of dental benefits, when covered, varies widely and is often quite limited, which can result in high out-of-pocket costs among those with serious dental needs or unmet need.

Policymakers are now discussing options to make dental care more affordable by broadening dental coverage for people on Medicare. President Biden’s FY 2022 budget request includes as part of the President’s healthcare agenda “improving access to dental, hearing, and vision coverage in Medicare.” Senate Democrats recently announced an agreement to include Medicare expansions, including dental, vision, and hearing, as part of the budget reconciliation package, though details of the agreement have not yet been released. In 2019, the House of Representatives passed the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R.3) that would add a dental benefit to Medicare Part B, along with a vision and hearing benefit, in addition to provisions to reduce prescription drug costs. Earlier this year, Representative Doggett, joined by 76 members of the House of Representatives, introduced the Medicare Dental, Vision, and Hearing Benefit Act (H.R. 4311) which would cover these benefits under Medicare Part B.

In light of these ongoing policy discussions, this brief provides new data on the share of Medicare beneficiaries with dental coverage, the share with a dental visit in the past 12 months, and out-of-pocket spending on dental care. It also takes a closer look at the scope of dental benefits offered to Medicare Advantage enrollees in individual plans in 2021. We focus on Medicare Advantage plans because they have become the leading source of dental coverage among Medicare beneficiaries. Our analysis draws from multiple datasets, including the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey for information on dental visits and out-of-pocket dental costs and the Medicare Advantage Enrollment and Benefit files for data on individual Medicare Advantage plans. To present a more detailed picture of dental benefits beyond what’s available in these data sets, we examine dental coverage offered by 10 geographically dispersed Medicare Advantage plans offered by different insurers with relatively high enrollment that offer dental benefits (see Methodology and Appendix for more information).

Key Findings

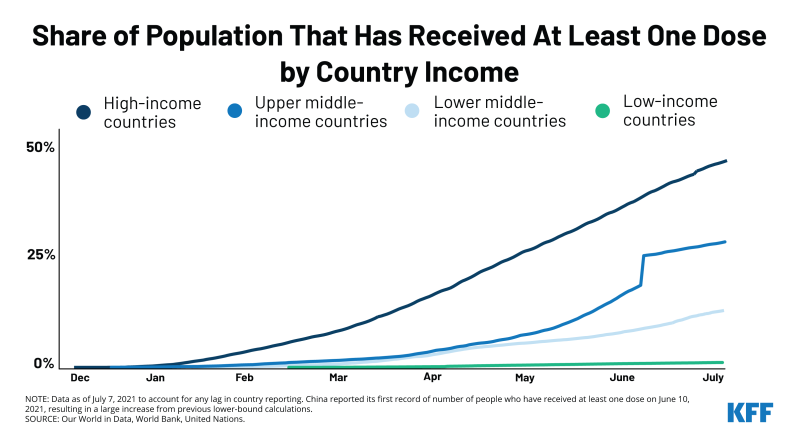

- Nearly half of Medicare beneficiaries (47%), or 24 million people, do not have dental coverage, as of 2019.

- Almost half of all Medicare beneficiaries did not have a dental visit within the past year (47%), with higher rates among those who are Black (68%) or Hispanic (61%), have low incomes (73%), or who are in fair or poor health (63%), as of 2018.

- Average out-of-pocket spending on dental services among Medicare beneficiaries who had any dental service was $874 in 2018. One in five Medicare beneficiaries (20%) who used dental services spent more than $1,000 out-of-pocket on dental care.

- In 2021, 94% of Medicare Advantage enrollees in individual plans (plans open for general enrollment), or 16.6 million enrollees, are in a plan that offers access to some dental coverage. Among these Medicare Advantage enrollees:

- Most (86%) of these enrollees are offered both preventive and more extensive dental benefits.

- More than three in four (78%) Medicare Advantage enrollees offered more extensive coverage are in plans with annual dollar limits on dental coverage, with an average limit of $1,300 in 2021; more than half (59%) of these enrollees are in a plan with a maximum dental benefit of $1,000 or less.

- Nearly two-thirds of enrollees (64%) with access to preventive benefits, such as oral exams, cleanings, and/or x-rays, pay no cost sharing for these services, though their coverage is typically subject to an annual dollar cap.

- The most common coinsurance for more extensive dental services, such as fillings, extractions, and root canals, is 50%.

- About 10% of Medicare Advantage beneficiaries are required to pay a separate premium to access any dental benefits.

Dental Coverage, Utilization and Out-of-Pocket Spending

Nearly 24 million people, or about half of all Medicare beneficiaries (47%), did not have any form of dental coverage in 2019 (Figure 1).

The remaining Medicare beneficiaries have access to dental coverage through Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid, and private plans, including employer-sponsored retiree plans and individually purchased plans.

In 2019, 29% of all Medicare beneficiaries had access to some dental coverage through Medicare Advantage plans (including 3% of beneficiaries also eligible for Medicaid who had access to dental coverage through a Medicare Advantage plan). Another 16% had coverage through private plans. About 11% of Medicare beneficiaries had access to dental coverage through Medicaid (including the aforementioned who also have coverage through Medicare Advantage plans). With the rise of Medicare Advantage enrollment, a growing share of Medicare beneficiaries have access to some dental coverage through their Medicare Advantage plan, so the share of all Medicare beneficiaries with some dental coverage would likely be higher in 2021.

A prior KFF analysis of the 2016 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) and other data sources indicated that nearly two-thirds of people on Medicare (65%) had no dental coverage that year. However, due to a data collection and processing issue subsequently identified by CMS, the estimates for private dental coverage derived from the MCBS were lower than they should have been by an unknown magnitude. CMS resolved this issue in 2017. Due to this and other methodological changes in our analysis, as explained in the methodology, estimates of the number of people on Medicare with dental insurance cannot be trended using our 2016 estimate.

Lack of dental care can exacerbate chronic medical conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, contribute to delayed diagnosis of serious medical conditions, and lead to preventable complications that sometimes result in costly emergency room visits.1 Limited or no dental coverage and cost concerns contribute to Medicare beneficiaries foregoing routine and other dental procedures.

Utilization. In 2018, half of Medicare beneficiaries did not have a dental visit (47%) – with even higher rates reported among those who are Black or Hispanic (68% and 61%, respectively) (Figure 2).

When we looked by race and gender, we found a larger share of Black and Hispanic women (64% and 59%, respectively) went without any dentist visit in the past year than White women (40%). The same pattern exists among men: a larger share of Black (74%) and Hispanic (64%) men than White men (44%) went without a dental visit.

Low-income beneficiaries are far less likely than higher-income beneficiaries to report a dental visit in the prior year. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of Medicare beneficiaries with incomes of less than $10,000 per year did not visit a dentist, as compared to 25% of beneficiaries with incomes above $40,000.

Health status was also correlated with dental care. Nearly two-thirds (63%) of all beneficiaries in fair or poor self-assessed health had a dental visit in the past year, as compared to 41% of beneficiaries in excellent, very good, or good health.

These relatively low rates of dental use are not attributable to a drop in utilization caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as they are based on 2018 data, the most recent year available, which was prior to the pandemic.

Out-of-Pocket Spending. Most beneficiaries who received dental services in 2018 (88%) paid out of pocket for their care. Across all beneficiaries, average out-of-pocket spending on dental care was $454 in 2018, although this includes a large number of beneficiaries who did not have any dental care that year. Among the roughly half of all Medicare beneficiaries who used any dental services, average out-of-pocket spending on dental care was $874 in 2018. One in five beneficiaries who used dental services spent more than $1,000 out-of-pocket on dental care, including one in ten that spent more than $2,000 (Figure 3).

Medicare Advantage Dental Benefits

Medicare Advantage plans may provide extra (“supplemental”) benefits that are not covered under traditional Medicare, such as dental, vision, hearing, and fitness benefits. The cost of these benefits may be covered using rebate dollars. Plans can also charge additional premiums for such benefits. In 2021, 94% of Medicare Advantage enrollees in individual plans, have access to some dental coverage. The majority (86%) of these Medicare Advantage enrollees have access to a plan with more extensive coverage, while 14% had access to preventive coverage only. Preventive dental coverage under Medicare Advantage plans generally includes oral exams, cleanings, dental x-rays, and sometimes fluoride treatments. More extensive benefits cover a range of services, including restorative services (e.g., fillings), endodontics (e.g., root canals), periodontics (e.g., scaling and root planing), prosthodontics (e.g., dentures, dental implants), and oral surgery.

The Scope of Covered Dental Benefits Varies Across Medicare Advantage Plans

Virtually all Medicare Advantage enrollees in plans that offer access to dental benefits (including if they have to pay a premium for those benefits), have access to preventive services, including oral exams (100%), cleanings (100%), and x-rays (99%), although fewer enrollees have access to fluoride treatment (59%).

Service Limits. Medicare Advantage plans typically limit the frequency of obtaining certain covered services during defined time frames. For example, nearly all enrollees (88%) are in plans that have frequency limits on the number of cleanings, with the most common limit being twice per year. For other services, such as x-rays, the frequency limits vary more across plans. For example, 36% of enrollees are in plans that limit the number of x-rays to a specified time frame, with the most common limit being once per year.

Covered Services (Other Than Preventive). Among enrollees in plans that offer access to more extensive services, the type of covered services varies across plans: 96% of enrollees are in plans that offer restorative services, such as fillings; 83% are in plans that cover extractions; 76% are in plans that cover periodontics and/or prosthodontics; 64% are in plans that cover endodontics, such as root canals; and 60% are in plans that cover diagnostic services and/or non-routine services. However, we did not examine frequency limits for more extensive services because these service categories encompass a variety of treatments, and it is not always clear what an individual plan covers in each of these service categories.

like other dental benefits, coverage for dentures varies across plans

As part of the prosthodontics service category, some beneficiaries may have access to coverage for dentures, a commonly needed service among older adults. As of 2018, nearly 14% of adults 65 and older are edentulous, meaning they have no natural teeth. We were unable to determine specifics about denture coverage based on the analysis of national data, so we looked at the ten illustrative plans in more detail. Five of the ten plans specified that they covered dentures (partial and full) and each of these plans limit dentures to 1 set every 5 years (Appendix Table 1). Among these five plans, cost sharing imposed on beneficiaries for dentures ranges from no copayment to a $500 copayment, and 50% to 70% coinsurance. All of these cost-sharing amounts are for in-network dental providers. Four out of the five plans have annual caps toward covered services, while one plan does not specify if it has an annual cap. The other five plans that offered dental coverage did not specify if dentures were covered.

Medicare Advantage Plans That Offer Dental Benefits Typically Have an Annual Dollar Cap on Dental Coverage

Most Medicare Advantage enrollees have access to more extensive benefits and the majority (78%) of these enrollees are in plans that impose a maximum annual dollar cap on the amount the plan will pay for dental care. Some plans just cap the amount they will pay for the relatively extensive dental benefits (with no cap on preventive services), but the majority of enrollees are in plans that cap cost sharing for both preventive and more extensive services.

The average annual limit on dental coverage among plans that offer more extensive benefits is about $1,300 in 2021, and more than half (59%) of enrollees in these plans have dental benefits that are capped at $1,000 or less (Figure 4).

About 16% are in a plan that pays up to $500, while 22% of enrollees are in plans with a $2000 annual limit, and 8% of enrollees are in plans with a limit greater than $2,000 and up to $5,000. Coverage limits are far more common among plans that cover more extensive benefits than plans that cover only preventive services.

Preventive Services Are Often Covered Without Cost Sharing (Subject to Annual Dollar Limits); For More Extensive Dental Services, 50% Coinsurance and Caps Are the Norm

Medicare Advantage plans’ cost sharing for dental benefits varies across plans and by service category – some plans do not charge any cost sharing (primarily for preventive services), while others charge coinsurance and/or a flat copayment.

- Preventive Services. Nearly two-thirds of enrollees (64%) in plans with access to oral exams, cleanings, and/or x-rays do not pay cost sharing for these services, although the majority of these enrollees are in plans that have annual limits on covered preventive services. An additional 8% of enrollees may have preventive services bundled as part of an office visit, which means they may only pay cost sharing for the visit itself, or in other cases, may have additional cost sharing for each individual service. About 3% of enrollees are in plans that require them to pay some type of cost sharing, which varies across plans. About 25% are in plans that do not report their cost-sharing amounts for these preventive services.

- More Extensive Dental Services. For plans that offer more extensive benefits and require cost sharing, coinsurance is more common than copayments, and the most common coinsurance amount is 50% across the more extensive service categories, including restorative services, extractions, endodontics, periodontics, prosthodontics, non-routine services, and diagnostic services.

- Cost sharing for more extensive dental services varies across plans (and services) and are typically subject to annual plan limits. For example, 39% of enrollees that are offered endodontic services (e.g. root canals) are in plans that do not require cost sharing for these services, but the majority of these enrollees are subject to an annual maximum on dental coverage. Another 30% are required to pay coinsurance for endodontic services – most often 50% – and also typically with an annual maximum. Among the remainder, 15% are required to pay copayments for endodontic services, and 15% of plans did not include data on cost-sharing amounts.

Among the ten illustrative Medicare Advantage plans with dental coverage, only one charges any cost sharing for preventive services ($10 copayment per service), though almost all plans (7) include an annual limit. Among the nine plans that offer more extensive dental services, five of the plans charge coinsurance, each of which is subject to an annual plan limit, with coinsurance ranging from 20% to 70% depending on the service, with 50% as the most common coinsurance amount across service categories. One of the plans requires copayments for more extensive dental benefits that vary depending on the service category (no annual maximum specified). Two plans that cover more extensive services do not require coinsurance or copayments; one of these plans has an annual limit ($2,300), while the other does not specify an annual limit.

Some Medicare Advantage Enrollees Must Pay a Separate Premium for Any Dental Coverage

Overall, 10% of Medicare Advantage enrollees in individual plans are required to pay a monthly premium to access any dental benefits, either preventive benefits only or more extensive benefits. For these enrollees, premiums average $270 per year, ranging from about $108 per year to $692 per year.

Some Medicare Advantage enrollees are in a plan where they are offered an option to pay a premium for additional dental benefits beyond those included in their plan, and some of these plans include vision and hearing benefits as part of that coverage. Dental premiums are in addition to premiums for other Medicare Advantage benefits, as well as the Medicare Part B premium ($148.50 in 2021).

Medicare Advantage Plans Tend to Limit Coverage to In-Network Providers or Charge More for Out-of-Network Care

Medicare Advantage plans that offer dental coverage may require enrollees to receive all covered services from in-network dental providers or impose additional cost sharing for services delivered out-of-network. Due to data limitations, we were unable to assess cost-sharing requirements for out-of-network dental care across all Medicare Advantage plans, so instead reviewed the practices of the 10 Medicare Advantage plans selected for this analysis.

Among the 10 illustrative Medicare Advantage plans, three plans do not cover any out-of-network dental care (Appendix Table 1). Two plans pay for out-of-network care “up to a certain amount” (amount not specified), with the patient billed for the remainder of the charges. Two plans impose coinsurance ranging from 50-55% for more extensive services received out-of-network, and another plan imposes 30% coinsurance for preventive services and 70% coinsurance for more extensive services delivered out-of-network. One plan covers out-of-network dental care for emergencies only, paying a maximum of $100 for any other out-of-network service. Finally, one plan covers 100% of preventive services received out-of-network.

How Medicare Advantage Dental Coverage Compares to Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace Coverage

As context for assessing the scope of dental benefits offered to Medicare Advantage enrollees, we reviewed dental coverage available to those who purchase dental coverage through the ACA Marketplaces. Adults purchasing plans through the ACA Marketplace may have dental coverage as part of their medical plan, or may choose to purchase separate stand-alone dental coverage. Among stand-alone dental plans available to adults on HealthCare.gov in 2021 (the federal marketplace), 100% cover routine preventive dental services (e.g. exams, cleanings, x-rays), 97% cover basic dental care (e.g. fillings, extractions, gum disease treatment, and root canals), and 81% cover major dental care (e.g. crowns, bridges, and dentures). Unlike the analysis of Medicare Advantage plans, the data on the ACA Marketplace is not enrollment-weighted.

Like Medicare Advantage plans, most plans have little to no cost sharing for preventive services. For adult routine dental coverage, most plans charge no coinsurance (57% of dental plans), followed by no coinsurance after meeting the dental deductible (32%). The median dental deductible for an individual is $50. For adult basic dental care, the most common cost sharing amount is 50% coinsurance after meeting the dental deductible (40% of plans that cover this benefit).

Similarly, for adult major dental care, the most common cost sharing amount is 50% coinsurance after meeting the deductible (58% of plans that cover this benefit). These most common coinsurance amounts for basic and routine dental coverage are the same as those in Medicare Advantage plans for more extensive services (50% coinsurance), though most Medicare Advantage plans do not first charge a deductible. All of these coinsurance rates for the ACA Marketplace dental plans are for in-network providers.

Most plans on the ACA Marketplace have an annual limit the plan will pay toward covered services, typically ranging from $1,000 to $2,000. For stand-alone dental coverage, premiums vary slightly depending on the age of the enrollee. For an adult age 40, the average premium in 2021 is $290 per year, and ranges from $97 per year to $780 per year.

How Current Proposals Would Add a Dental Benefit to Medicare

In the 116th Congress, the House of Representatives passed the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act (H.R.3), which among many provisions, provided for dental coverage under Part B of the Medicare program, starting in 2025 if enacted into law. Medicare would cover 80% of the cost of preventive services and basic treatments, and would phase up coverage for more major treatments, covering 10% of the cost in 2025, increasing 10 percentage points per year to 50% in 2029 and thereafter. The Congressional Budget Office estimated this benefit would cost almost $238 billion over 10 years (2020-209). The recently reintroduced version of H.R. 3 does not include coverage for a dental benefit.

Representative Doggett introduced the Medicare Dental, Vision, and Hearing Benefit Act (H.R. 4311) in July 2021 that would provide dental coverage under Medicare Part B. In contrast to H.R.3, the proposal, according to a press release, would require no coinsurance for preventive services, and impose a 20% coinsurance for more extensive benefits, which is similar to how the Part B benefit is structured for physician and other outpatient services, and is lower than the 50% coinsurance typically charged by Medicare Advantage plans.

Discussion

Since its enactment in 1965, Medicare has not covered routine dental care and half of Medicare beneficiaries (47%) do not have any dental coverage, as of 2019. Without dental coverage, many people on Medicare forego needed and routine dental care – an issue that disproportionately impacts communities of color – with significantly fewer visits to the dentist in the past year among Black and Hispanic beneficiaries (68% and 61%, respectively) compared to White beneficiaries (42%). Untreated oral health can exacerbate certain chronic diseases, delay diagnosis of serious health conditions, and result in costly emergency visits. Further, among beneficiaries who have the ability to pay for dental treatment, many experience high out-of-pocket costs, with 20% of people spending more than $1,000 out-of-pocket on dental care.

Medicare Advantage plans are the leading source of dental coverage for people with Medicare. While the scope of dental coverage varies across Medicare Advantage plans, there are some common features: virtually all Medicare Advantage enrollees with access to dental coverage as part of their plan have preventive benefits, and most have access to more extensive dental benefits, though cost sharing for more extensive services is typically 50% for in-network care, and subject to an annual cap on plan payments. More than three out of four (78%) enrollees with access to more extensive services are subject to annual caps – averaging about $1,300 in 2021.

In conducting this analysis, we found that plans do not use standard language when defining their benefits and include varying levels of detail, making it challenging for consumers or researchers to compare the scope of covered benefits across plans.

Given the continued interest in adding a dental benefit to Medicare, policymakers will need to weigh a variety factors in designing this benefit, including the scope of covered benefits, cost sharing for specific services, and how different levels of dental coverage may affect Medicare costs and premiums.

Meredith Freed, Nancy Ochieng, Nolan Sroczynski, and Krutika Amin are with KFF.

Anthony Damico is an independent consultant.

Methodology

Methodology

This analysis uses data from multiple sources: Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS), 2018 and 2019; Medicare Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse data from 20 percent of beneficiaries (20% Sample), 2019; and CMS Medicare Advantage Enrollment and Benefit files, 2019 and 2021. The analysis also uses data from the Center for Health Care Strategies’ (CHCS) Medicaid Adult Benefits data, updated September 2019.

To determine dental coverage in Figure 1, we combined data from multiple sources. The 20% Sample and Medicare Advantage Benefits files, 2019 were used to determine the number of Medicare Advantage enrollees with access to dental coverage. The 20% Sample, combined with data from CHCS 2019, was used to calculate the number of full dual eligible beneficiaries with some dental coverage based on whether they lived in a state that offered adult dental benefits through Medicaid. While we use CHCS data for dental coverage for adults, it is possible that not all duals are covered by adult dental benefits because the benefit may vary based on eligibility pathway. Private dental coverage was calculated using the share of MCBS 2019 responses to questions about whether a beneficiary has dental coverage, and then using that share to calculate a comparable number of people with private dental coverage using the 20% Sample for estimates of all Medicare beneficiaries. The populations are those with both Parts A and B in March of 2019, excluding the US territories. Had we included those with Part A-only, which is primarily people who have employer-based coverage or some public retirees, the number and share with private dental coverage would be higher.

This analysis of Medicare dental coverage differs from KFF’s analysis of dental coverage in 2016 in several ways, and therefore this data cannot be trended using our 2016 estimate. CMS identified a data collection and processing issue in the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey 2016 data that resulted in lower estimates of private dental coverage than should have been reported based on actual survey responses. CMS resolved this issue in the 2017 MCBS. In our prior analysis, full dual eligible beneficiaries who lived in states with adult emergency-only dental coverage were considered to have dental coverage. However, in this analysis, they are not considered to have dental coverage because emergency-only coverage does not compare to most coverage provided under Medicare Advantage or private plans; Medicare also provides some emergency-only coverage. There were 16 states that we codified as not providing dental coverage to adults on Medicaid based on CHCS data: AL, TN, MD (no coverage); AK, AZ, FL, GA, ME, MS, NV, OK, TX, UT, WV (emergency-only coverage); and NH, DE (dental benefit was under development in 2019). We excluded from the total 4.4 million Medicare Advantage enrollees who are in employer-group health plans from this analysis (but not in the prior analysis) because information describing supplemental benefits, including dental coverage, are not available. Finally, in our prior analysis, we combined estimates from the 20% Sample and MCBS to determine the total number of Medicare beneficiaries in 2016, whereas the 2019 total population is derived from the 20% Sample.

The 2018 MCBS Cost Supplement file was also used to look at visits to the dentist, and out-of-pocket costs for dental services. MCBS Cost Supplement data from 2019 are not yet available for these variables.

The Medicare Advantage Enrollment and Benefit files for 2021 were used to look at dental coverage for beneficiaries enrolled in individual Medicare Advantage plans (e.g. excludes Special Needs Plans and employer-group health plans). This analysis includes enrollees in Puerto Rico and other territories. Plans with enrollment of 10 or fewer people were also excluded because we are unable to obtain accurate enrollment numbers.

To supplement the Medicare Advantage analysis, we examined the scope of dental coverage offered by ten Medicare Advantage plans in greater detail. We reviewed 2021 Medicare Advantage plans with the highest enrollment, and among these highest enrollment plans, we selected 10 geographically dispersed plans, taking into account variations across firms and a mix of HMO and PPO plans. As part of this illustrative analysis, we examined a variety of aspects of Medicare Advantage plans including premiums, annual caps, coinsurance/copayments, covered services, and networks, among others.

The Healthcare.gov 2021 QHP landscape data was used to look at plans available on the ACA Marketplace. This data only includes dental information from the federal marketplace; states that have their own marketplaces are not represented in this data. Child-only plans were excluded. Data used in this analysis was not enrollment-weighted.

Appendix

Endnotes

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health, 2000; Schenkein HA, Loos BG. Inflammatory mechanisms linking periodontal diseases to cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol 2013;40 (Suppl. 14):S51–S69 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jcpe.12060; Teeuw WJ, Gerdes VE, Loos BG. Effect of periodontal treatment on glycemic control of diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2010;33(2):421-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2809296/pdf/zdc421.pdf; Preshaw PM, Alba AL, Herrera D, et al. Periodontitis and diabetes: a two-way relationship. Diabetologia 2011;55(1):21-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3228943/#CR7; Allareddy V, Rampa S, Lee MK, et al. Hospital-based emergency department visits involving dental conditions. The Journal of the American Dental Association 2014;45(4):331–337. https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(14)60010-6/fulltext; Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Thorpe JM, Xiang Q, Szabo A. Patient characteristics and trends in nontraumatic dental condition visits to emergency departments in the United States. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent 2012;4:1-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3652363/ ↩︎