State Medicaid Home & Community-Based Services (HCBS) Programs Respond to COVID-19: Early Findings from a 50-State Survey

Issue Brief

Key Takeaways

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a public health emergency that was unprecedented in its scope and duration and brought new focus to the long-standing unmet need for home and community-based services (HCBS) among seniors and people with disabilities and direct care workforce shortages. Recognizing Medicaid’s role as the primary payer for HCBS, this issue brief presents early findings from the most recent KFF 50-state survey of Medicaid HCBS programs. It focuses on state policies adopted in response to challenges posed by the pandemic, the pandemic’s impact on Medicaid HCBS enrollees and providers, and states’ early plans for the new American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) 10 percentage point temporary increase in federal Medicaid matching funds for HCBS. We survey states about HCBS provided through state plan authorities and waivers. There were 277 HCBS waivers in FY 2018. Overall, 41 states responded to the survey by mid-July 2021, accounting for 87% of total HCBS spending nationally in FY 2018, though response rates for specific questions varied. We highlight some specific state examples where states provided additional information with their responses. Key finding include the following:

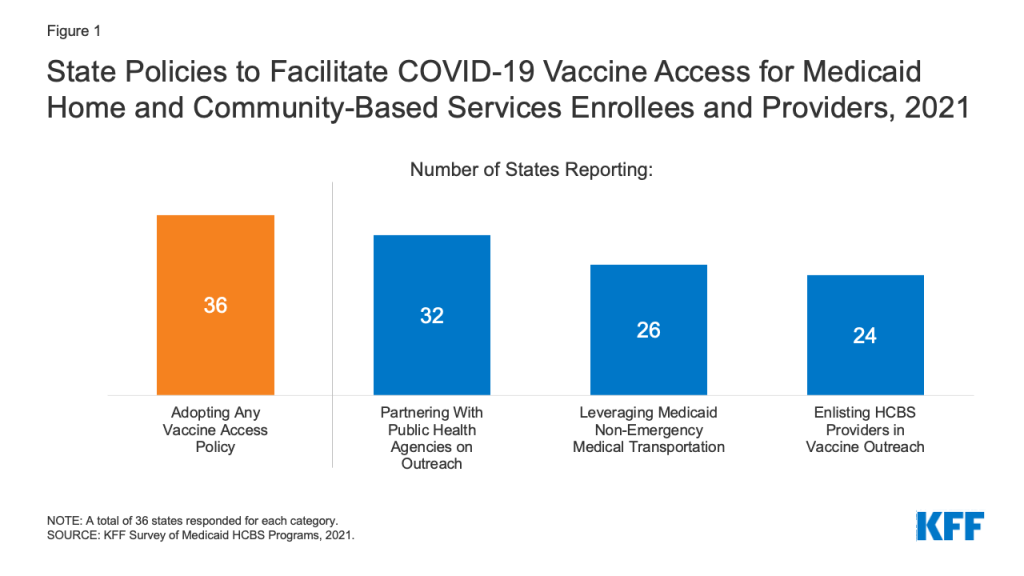

- Important data gaps remain, with just under half of responding states tracking COVID-19 vaccination rates among Medicaid HCBS enrollees. At the same time, state HCBS programs are playing a role in facilitating vaccine access for HCBS enrollees, with most responding states adopting multiple policies in this area. Over one-third of responding states have publicly available data on COVID-19 cases and deaths among HCBS enrollees.

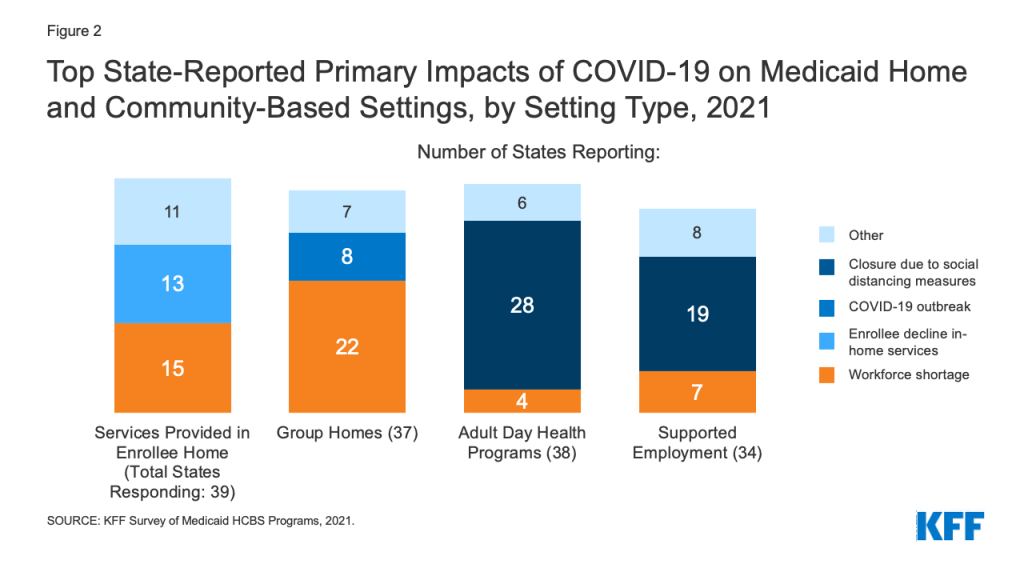

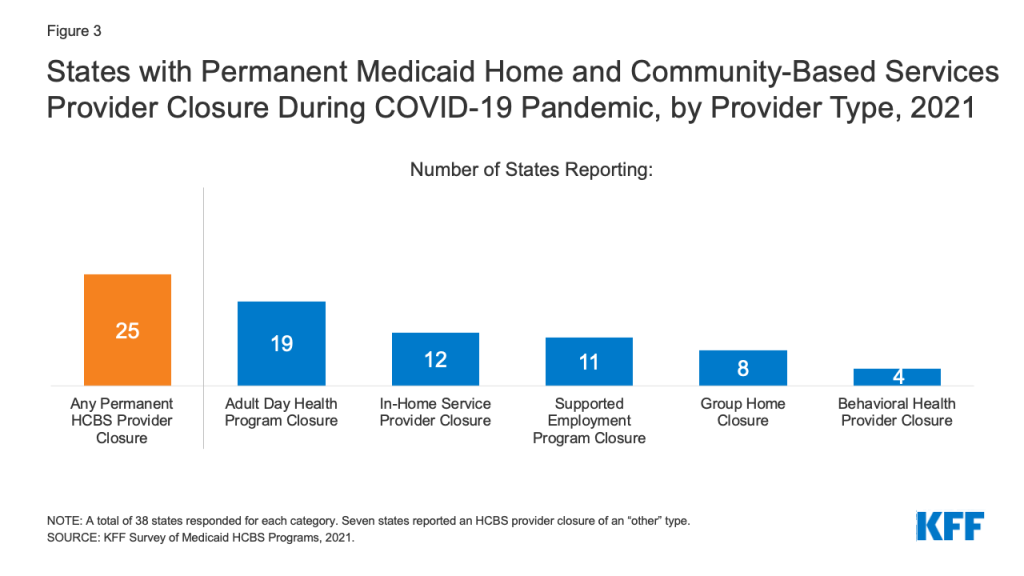

- The Medicaid HCBS provider infrastructure declined during the pandemic, with two-thirds of responding states reporting a permanent closure of at least one provider. Most of these states reported permanent closures among more than one HCBS provider type. States most frequently cited workforce shortages as the pandemic’s primary impact on in-home and group home services, while closures due to social distancing measures was the most frequently reported primary impact on adult day health and supported employment programs.

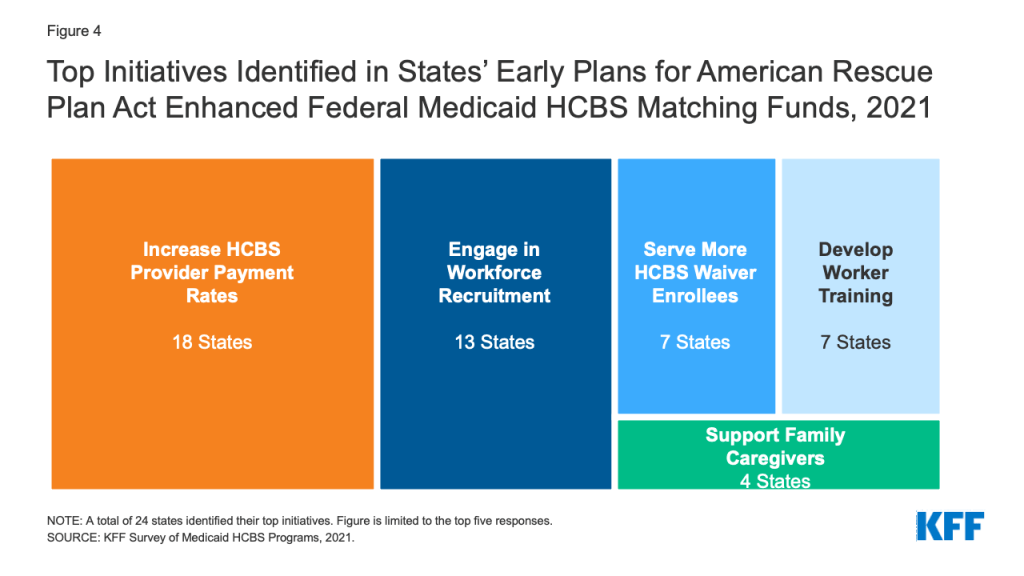

- Over half of responding states reported early plans for the new ARPA temporary enhanced federal funds for Medicaid HCBS. The most frequently reported activities were provider payment rate increases and workforce recruitment.

Expanding HCBS access and strengthening the direct care workforce would help to improve care as pandemic recovery efforts continue and beyond, while also increasing public spending. While the ARPA enhanced funds are available only for one year, additional federal funding for HCBS is part of the budget reconciliation package proposed by Democratic leaders, though the details will be worked out by Congressional committees. President Biden earlier this year proposed a $400 billion federal investment in Medicaid HCBS, though it is unclear how much of that funding increase will be approved by Congress as it considers competing priorities in the budget package.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a public health emergency (PHE) that was unprecedented in its scope and duration. Key Medicaid populations, including seniors and nonelderly people with disabilities who use long-term services and supports (LTSS), are disproportionately at risk of serious illness or death from COVID-19 compared to the general population. This risk is heightened for people who receive LTSS in congregate settings and for the direct care workers who provide these services. The pandemic’s impact on these populations brought new focus to pre-existing issues, including unmet need for home and community-based services (HCBS) and workforce shortages. Drawing on Medicaid’s role as the primary payer for LTSS, including HCBS, federal and state policymakers have adopted a number of policies to aid pandemic response.

This issue brief presents early findings from the most recent KFF survey of Medicaid HCBS programs in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. It focuses on state policies adopted in response to challenges posed by the pandemic, the pandemic’s impact on Medicaid HCBS enrollees and providers, and states’ initial plans for the new American Rescue Plan Act 10 percentage point temporary increase in federal Medicaid matching funds for HCBS available from April 2021 through March 2022. Additional survey findings and state-level data related to Medicaid HCBS enrollment, spending, and key state policies will be released later. We survey states about HCBS provided through state plan authorities and waivers. There were 277 HCBS waivers in FY 2018.1 Overall, 41 states responded to the survey by mid-July 2021, though response rates for specific questions varied.2 The 41 responding states account for 87% of total HCBS spending nationally in FY 2018. We highlight specific state examples where states provided additional information with their responses.

COVID-19 Impact on Medicaid HCBS Enrollees

Over one-third of responding states reported having publicly available data on COVID-19 cases and deaths among Medicaid HCBS enrollees.3 Though states are monitoring COVID-19 cases and deaths generally, and some are tracking overall cases and deaths by demographic characteristics such as age, race, and sex, fewer are collecting these data specifically for Medicaid HCBS enrollees. Among the 14 states reporting publicly available data specific to HCBS enrollees, 12 states’ responses to this question varied by waiver program. This suggests that even when states are tracking COVID-19 cases and deaths among HCBS enrollees, tracking may not be uniform across all HCBS programs. For example, Illinois reported that it makes COVID-19 cases and deaths data publicly available for three HCBS waivers serving people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD) but not for its HCBS waivers serving other populations.4 Rhode Island reported that efforts to track COVID-19 cases and deaths among its HCBS waiver enrollees are under development, though data are not yet publicly available.

Just under half of responding states reported tracking COVID-19 vaccination rates for Medicaid HCBS enrollees.5 Nearly all of these states indicated that these data are used internally to inform outreach efforts, while two states (Delaware and Indiana) noted that they make these data publicly available. Seven states’ responses to this question varied by HCBS program, again suggesting that tracking may not be uniform across all HCBS enrollees. In addition, Washington reported that it is beginning to track COVID-19 vaccination status among its Section 1115 HCBS waiver enrollees as part of the functional assessment process.

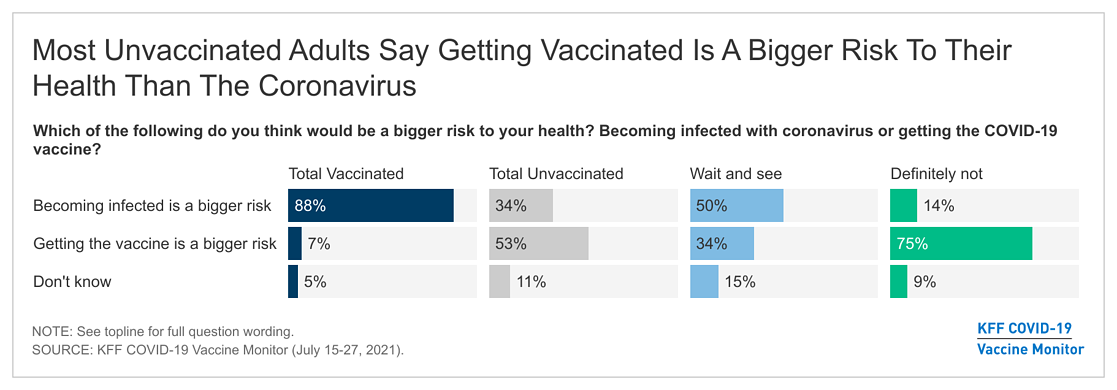

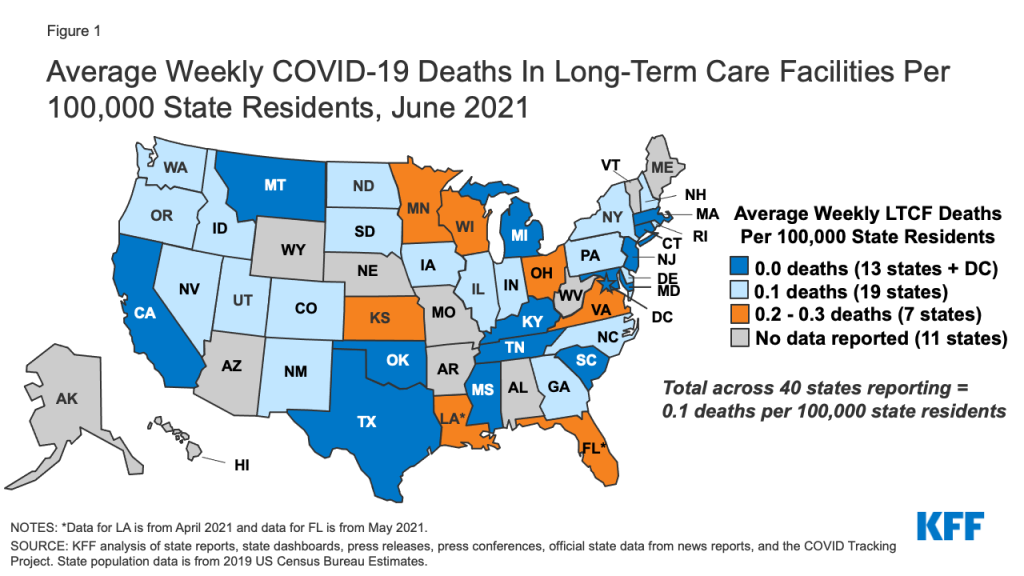

All responding states reported having at least one policy in place to facilitate access to COVID-19 vaccines for Medicaid HCBS enrollees and providers, with 8 in 10 responding states reporting more than one policy.6 The most frequently reported policy was partnering with public health agencies on vaccine outreach and education initiatives (Figure 1). For example, West Virginia provided a list of homebound HCBS enrollees to local health departments to arrange for appointments to administer vaccines in enrollees’ homes. Other frequently reported policies included leveraging Medicaid’s non-emergency transportation benefit to provide enrollees with access to vaccination appointments and enlisting HCBS providers in vaccine outreach and education efforts (Figure 1). Additional policies to facilitate vaccine access reported by states included placing certain HCBS populations in higher vaccine access priority groups, having Medicaid managed care plans contact enrollees to provide education and schedule vaccination appointments,7 and partnering with pharmacies to provide vaccination clinics for HCBS enrollees.8 Washington reported having “strike teams” travel to some HCBS settings to offer vaccinations to staff and enrollees.

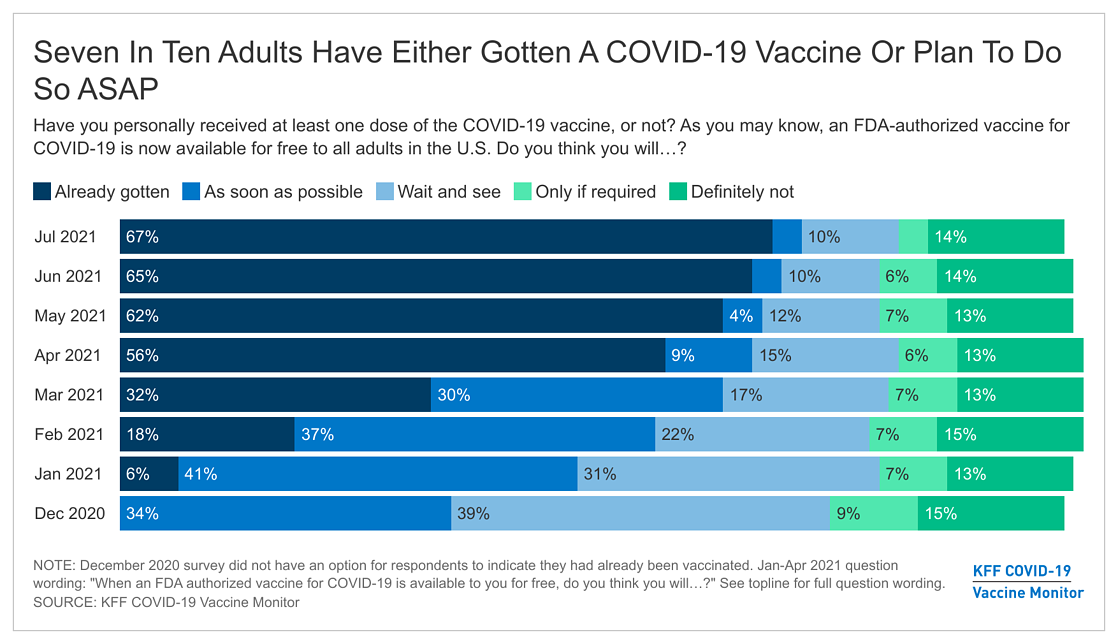

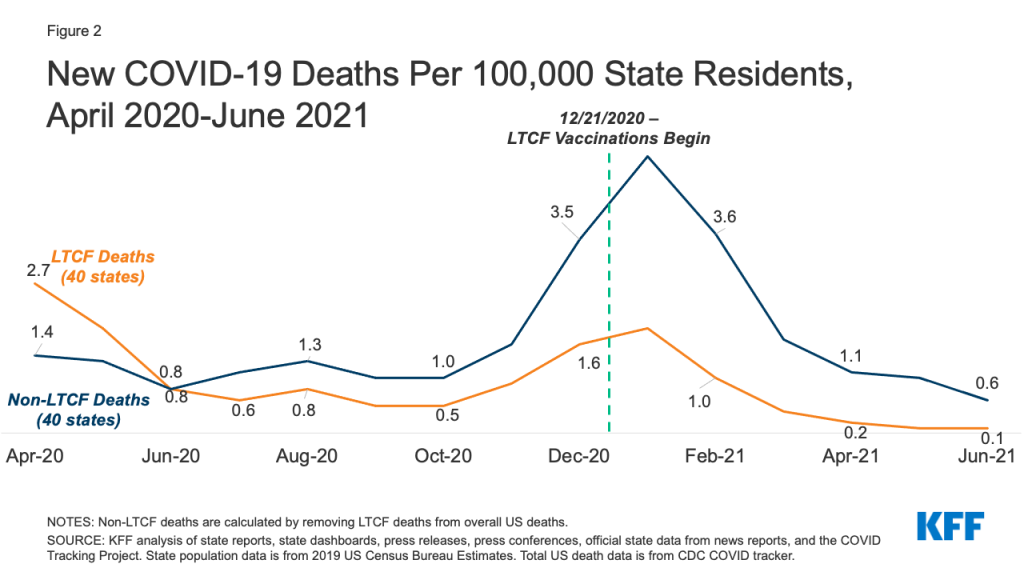

The pandemic affected all Medicaid HCBS settings, though the primary impact identified by states varied somewhat by setting type. States most frequently reported that the pandemic resulted in workforce shortages for HCBS provided in an enrollee’s home9 and in group homes,10 while closures due to social distancing measures was the most frequently reported impact for adult day health programs11 and supported employment programs12 (Figure 2). For HCBS provided in an enrollee’s home, workforce shortages was closely followed by enrollees declining to have workers in their homes (Figure 2). States reported that some HCBS enrollees and their family members declined services due to fear of coronavirus exposure and had concerns about receiving in-person services until enrollees and providers could be vaccinated. To minimize service interruptions, some states reported using Medicaid emergency authorities to provide HCBS via telehealth where possible to enrollees at home and in adult day health programs. Some states also noted that utilization of supported employment services dropped due to job loss during the pandemic among the enrollees who received these services.

Eight states identified COVID-19 outbreaks as the pandemic’s primary impact in group homes (Figure 2). (Other states also may have experienced outbreaks but did not identify them as the pandemic’s “primary” impact on group homes in their survey response.) Arizona provided additional detail about the pandemic’s impact on group homes, noting that group homes had to increase staffing to support HCBS enrollees during the day when outside day habilitation and supported employment programs became less available. In addition, Arizona noted that its group homes had to identify alternative places to quarantine residents exposed to coronavirus to mitigate the risk of spreading infection to other residents and staff.

COVID-19 Impact on Medicaid HCBS Providers

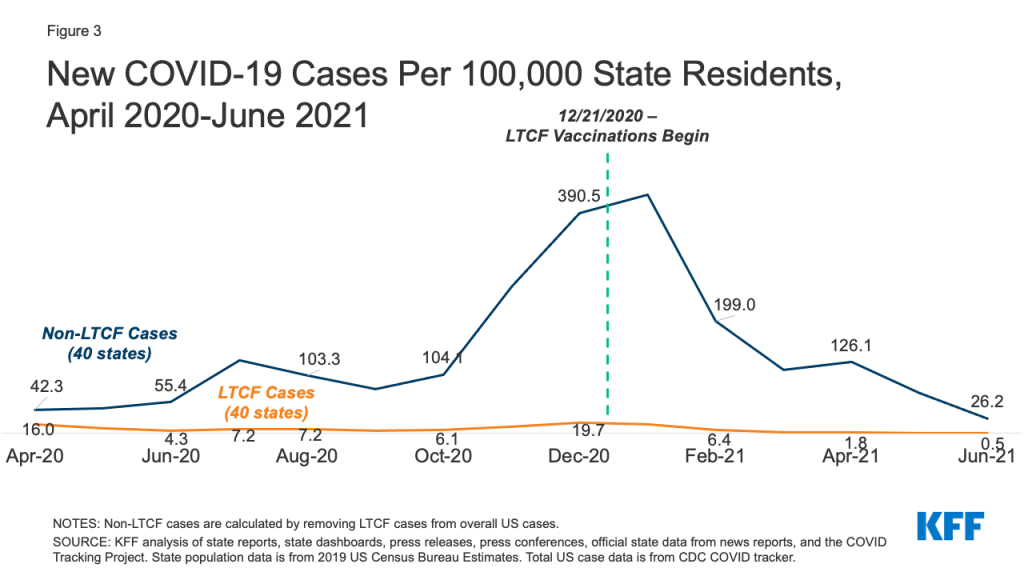

Two-thirds of responding states reported a permanent closure of at least one Medicaid HCBS provider during the pandemic (Figure 3).13 Most of these states (16) reported permanent closures among more than one HCBS provider type. Adult day health programs were the most frequently reported HCBS provider type to have permanently closed, followed by providers of in-home services, supported employment providers, and group homes (Figure 3). Several states indicated that workforce shortages already existed prior to pandemic and worsened during the COVID-19 PHE. For example, Oregon noted that HCBS providers experienced challenges with remaining financially viable due to the pandemic, which will impact their ability to reopen. Specific challenges cited by Oregon related to providers’ ability to maintain leased space, retain trained staff, and provide supported employment services such as job search, placement, and coaching.

About three-quarters of responding states reported that they used CMS-approved authority to provide retainer payments to financially support Medicaid HCBS providers during the pandemic.14 Retainer payments allow providers to continue to bill and be paid for habilitation and personal care services that are authorized in enrollee service plans, which is intended to help providers maintain capacity when circumstances prevent enrollees from actually receiving those services.15 For example, some HCBS providers such as adult day health centers had to temporarily close to comply with social distancing orders during the COVID-19 PHE, and some HCBS enrollees may have had to temporarily stop receiving in-home services due to self-quarantine.

Most responding states (20 of 29) reported that the initial federal limit of three 30-day episodes for retainer payments was insufficient to fully support HCBS providers during the pandemic.16 Some states’ responses to this question varied by HCBS program, indicating that the federal retainer payment limit may have been sufficient to support some service provider types but not others. For example, Pennsylvania reported the federal retainer payment limit was insufficient for I/DD service providers but was sufficient for providers serving enrollees in its waiver for seniors and people with physical disabilities. CMS’s initial guidance allowed states to make up to three 30-day episodes of retainer payments during the COVID-19 PHE.17 This guidance was in effect when we began fielding our survey in March 2021. Subsequent CMS guidance revised federal policy to allow states to offer retainer payments for up to three additional 30-day periods in calendar year 2021, recognizing the extended duration of the COVID-19 PHE.18

Early State Plans for ARPA HCBS Funding Increase

Nearly six in 10 responding states identified the top initiatives that they were planning to target with the new temporary enhanced federal Medicaid matching funds for HCBS in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).19 The ARPA increases the federal matching rate for state spending on HCBS by 10 percentage points from April 1, 2021 through March 31, 2022.20 States must maintain their current HCBS spending and use the enhanced funds for activities that expand or strengthen Medicaid HCBS. KFF previously estimated that this ARPA provision could increase federal Medicaid HCBS spending by about $11.4 billion nationally. The increase will be distributed proportional to the size of state HCBS programs, reflecting variation in both state size and optional policy choices. The ARPA was enacted just as our survey went into the field in March 2021, and survey responses reflect states’ early plans. States’ plans for the ARPA funds may change in light of CMS implementation guidance issued in mid-May 2021, and based on stakeholder input as states develop their formal plans to submit to CMS.

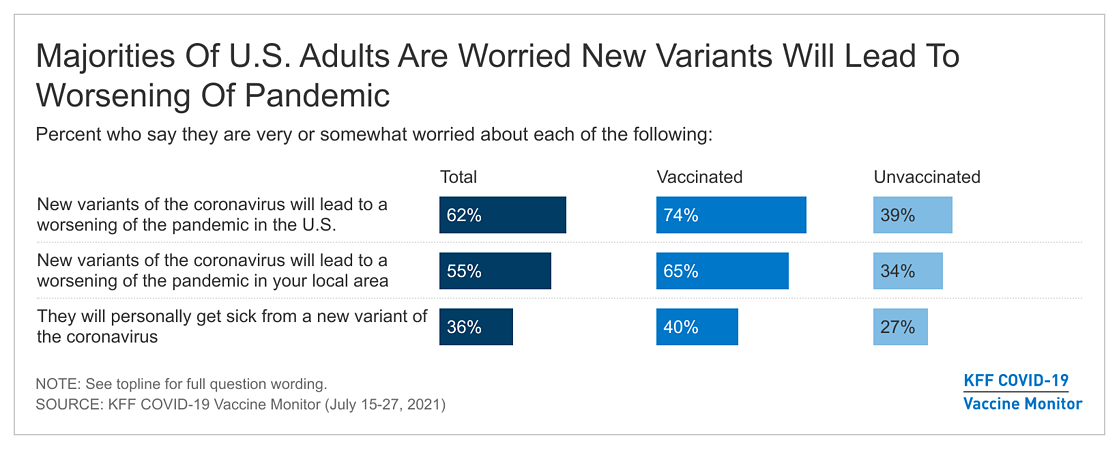

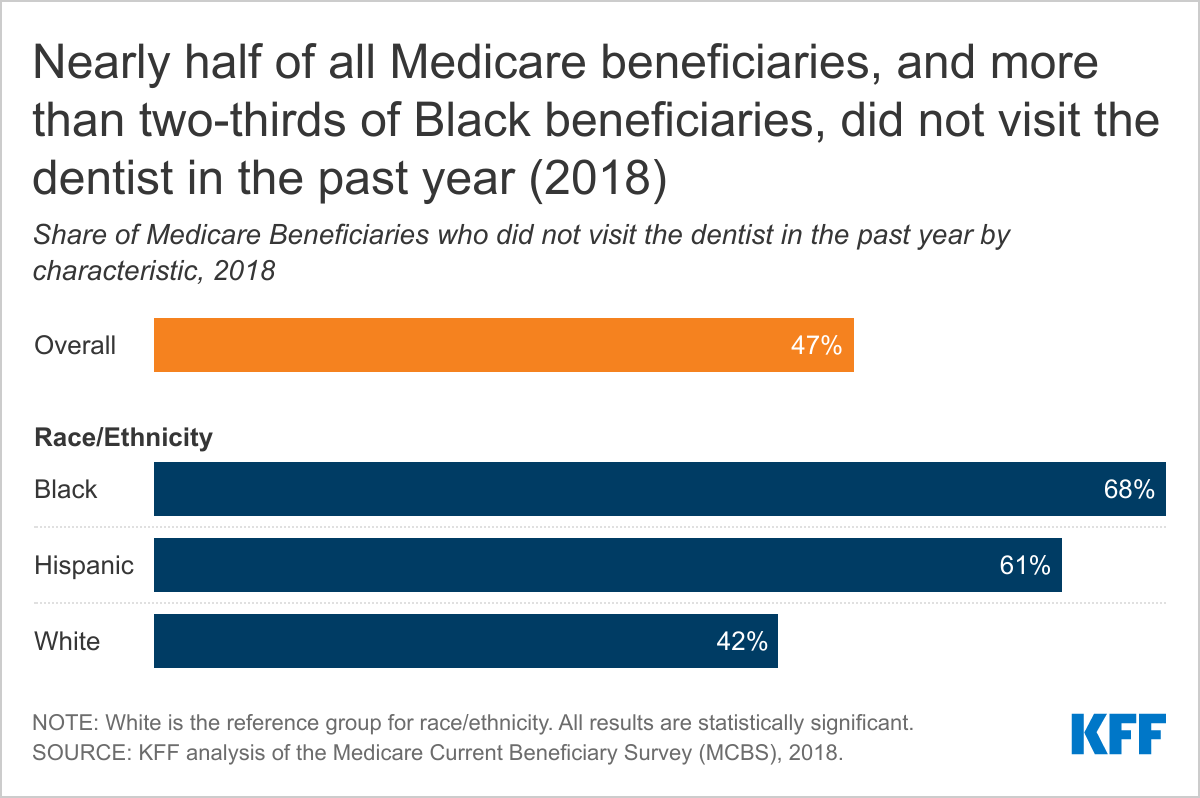

The two initiatives most frequently reported by states as potential uses of the new APRA funds were increasing HCBS provider payment rates and workforce recruitment (Figure 4). Other initiatives rounding out the top five included serving additional HCBS waiver enrollees, investing in worker training, and supporting family caregivers (Figure 4). Fewer states reported providing emergency equipment and supplies (4 states), providing worker hazard or overtime pay (3 states), providing retainer payments (3 states), providing services to mitigate enrollee isolation due to the pandemic (2 states), adding or increasing waiver services (2 states), and funding nursing home to community transitions (2 states) among their top anticipated uses of APRA funds. We asked states to identify their top two initiatives, though a number of states’ responses to this question varied by HCBS program with 14 states reporting three or more initiatives across different programs. The May 2021 CMS guidance clarified that states also can use ARPA funds to facilitate access to COVID-19 vaccines, so some states may include this initiative in their final plans.

Looking Ahead

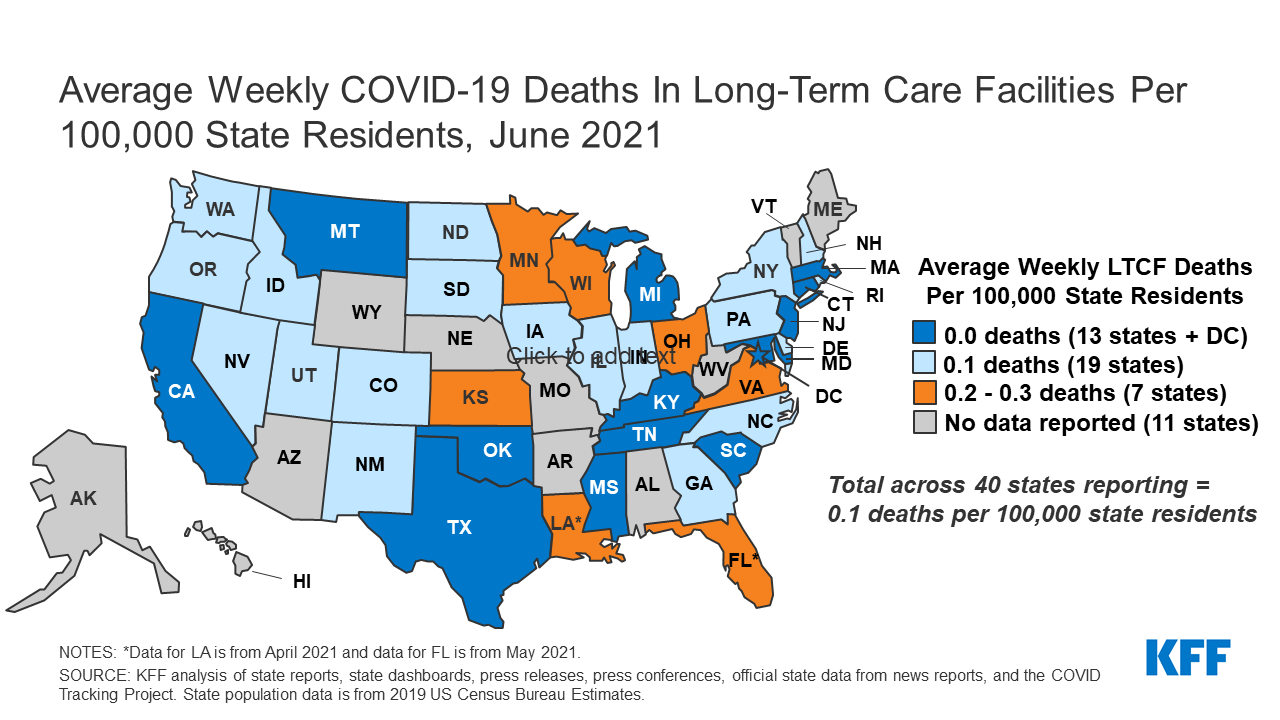

Understanding the pandemic’s impact on Medicaid HCBS enrollees and providers can help to inform ongoing pandemic response and recovery efforts. Important data gaps remain, with most states lacking publicly available data on COVID-19 cases and deaths among HCBS enrollees. While the availability of vaccines has led to substantial decreases in cases and deaths among those in LTSS settings, CMS has noted that ongoing vaccination efforts will be necessary due to workforce turnover and to ensure widespread vaccine access. Our survey results indicate that while some states are tracking vaccination rates among Medicaid HCBS enrollees, tracking is not yet uniform across all states and among all HCBS programs within states. A recent interim final rule adopting requirements for certain LTSS settings to report on, provide education about, and offer the COVID-19 vaccine to residents and staff applies to nursing homes but deferred establishing similar requirements for congregate community-based settings like group homes and adult day health centers. Until data, resource, and oversight gaps across the LTSS continuum are filled, nonelderly people with disabilities may continue to experience disproportionate barriers to vaccine access compared to people in nursing homes, and the full impact of COVID-19 on this population will not be understood completely. Despite limited efforts to track vaccination rates, our survey also found that state HCBS programs are playing a role in facilitating vaccine access for HCBS enrollees, with most states adopting multiple policies in this area. These efforts could be expanded if states choose to direct a portion of their ARPA enhanced HCBS funds to activities supporting COVID-19 vaccine access as permitted in recent CMS guidance.

The pandemic has brought new attention among policymakers and the public to the longstanding unmet need for HCBS and direct care workforce shortage, driven by low wages, high turnover, and limited opportunities for career advancement. Most states reported workforce shortages as the pandemic’s primary impact on HCBS provided in an enrollee’s home and in group homes. Many states also reported permanent closure of Medicaid HCBS providers during the pandemic, affecting adult day health centers, in-home service providers, supported employment providers, and group homes. Most states that reported provider closures experienced the loss of more than one provider type. Though many states reported using retainer payment authority to financially support providers, the original federal episode limit may have been insufficient to meet some providers’ needs, particularly those with narrow operating margins. Medicaid providers also faced challenges accessing federal provider relief funds, both in the amount of funding received and delays in allocations compared to other provider types.

Maintaining and increasing the HCBS provider infrastructure is key to meeting enrollee need and expanding access to these services as pandemic recovery efforts continue and beyond. The APRA one-year enhanced funds for HCBS represents the first new federal investment in Medicaid HCBS since the Affordable Care Act in 2010. States have adopted a number of policies to expand access to Medicaid HCBS during the PHE, such as expanding eligibility criteria, streamlining enrollment processes, adding services, and increasing provider payment rates, but their ability to continue many of these policies after the PHE ends may be limited by budgetary constraints. Our survey found that states’ initial plans for the new ARPA funds centered on provider payment rate increases and workforce recruitment, two areas which experience during the pandemic has confirmed are crucial to sustaining and expanding access to HCBS. While the ARPA enhanced funds are available only for one year, additional federal funding for HCBS is part of the budget reconciliation package proposed by Democratic leaders, though the details will be worked out by Congressional committees. President Biden earlier this year proposed a $400 billion federal investment in Medicaid HCBS, though it is unclear how much of that funding increase will be approved by Congress as it considers competing priorities in the budget package.

Endnotes

- The total number of HCBS waivers may differ somewhat for FY 2021. That data will be included in a subsequent report. ↩︎

- The 10 states that did not respond by mid-July 2021 are Connecticut, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Utah. ↩︎

- Thirty-nine states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Illinois reported that the state agencies operating its HCBS waivers for seniors, people with physical disabilities, and people with HIV/AIDS are reporting COVID-19 cases and deaths among those enrollees to local health departments, and managed care plans are tracking COVID-19 cases and deaths across several Illinois HCBS waivers, but this information is not publicly available. ↩︎

- Thirty-eight states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Thirty-six states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- This initiative was reported by five states (Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Ohio, and Virginia). ↩︎

- This initiative was reported by three states (Illinois, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin). ↩︎

- Thirty-nine states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Thirty-seven states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Thirty-eight states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Thirty-four states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Thirty-eight states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- Thirty-nine states responded to this survey question. Our survey asked states whether they actually used CMS-approved authority to provide retainer payments. KFF’s Medicaid emergency authorities tracker lists states with CMS-approved authority, without indicating whether states actually used an approved authority. This difference may account for discrepancies in state totals between the two sources. ↩︎

- Since 2000, CMS Olmstead guidance has permitted states to make retainer payments to personal care and attendant service providers while an HCBS enrollee who usually receives those services is hospitalized or absent from their home. This policy places personal assistance services on equal footing with nursing facility services, for which states are allowed to make bed hold payments in an enrollee’s absence. The 2000 guidance applies to personal assistance services provided through HCBS waivers and allows a retainer payment period of 30 consecutive days or the number of days for which the state allows a nursing facility bed hold payment, whichever is less. CMS’s Section 1115 COVID-19 demonstration waiver template allowed states to request authority to make retainer payments to habilitation and personal care service providers affected by the pandemic in an effort to preserve this provider network. CMS COVID-19 guidance clarified that retainer payment authority also is available as a regular state plan amendment or a disaster state plan amendment for Section 1915 (i) HCBS and Community First Choice attendant services as well as through HCBS waiver Appendix K. CMS, COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for State Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program Agencies, at pp. 101-102 (last updated Jan. 6, 2021), https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/downloads/covid-19-faqs.pdf. ↩︎

- Twenty-eight states responded to this survey question. One state reported that it used retainer payment authority but did not respond to this follow-up question. ↩︎

- Consecutive days are those that are eligible for billing, which means that 30 consecutive billing days for services provided Monday through Friday encompasses a 6-week period. CMS, COVID-19 FAQs, supra. n.16 at p. 99. ↩︎

- The revised policy is retroactive to January 1, 2021. CMS State Medicaid Director letter, SMD #21-003, Implementation of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 Section 9817: Additional Support for Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services during the COVID-19 Emergency, at p. 11 (May 13, 2021), https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/smd21003.pdf. ↩︎

- Forty-one states responded to this survey question. ↩︎

- States have until March 31, 2024 to spend the enhanced funds. ↩︎