Medicaid Coverage of Behavioral Health Services in 2022: Findings from a Survey of State Medicaid Programs

Medicaid plays a key role in covering and financing care for people with behavioral health conditions. Nearly 40% of the nonelderly adult Medicaid population (13.9 million enrollees) had a mental health or substance use disorder (SUD) in 2020. Most enrollees with behavioral health conditions qualify for Medicaid because of their low incomes. Behavioral health services are not a specifically defined category of Medicaid benefits: some may fall under mandatory Medicaid benefit categories (e.g., psychiatrist services may be covered under the “physician services” category), and states may also cover behavioral health benefits through optional benefit categories (e.g., case management services, prescription drugs, and rehabilitative services). Behavioral health services for children are particularly comprehensive due to Medicaid’s EPSDT benefit for children: children diagnosed with behavioral health conditions receive any service available under federal Medicaid law necessary to correct or ameliorate the condition. However, the same is not required for adults.

To better understand the variation in access to behavioral health services for adults in Medicaid, KFF surveyed state Medicaid officials about behavioral health benefits covered for adult enrollees in their fee-for-service (FFS) programs. These questions were part of KFF’s Behavioral Health Survey of state Medicaid programs, fielded as a supplement to the 22nd annual budget survey of Medicaid officials conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA). A total of 45 states (including the District of Columbia) responded to the behavioral health benefits survey. This issue brief uses the survey data to describe the landscape of behavioral health service coverage across states, including themes across and within service categories. Additional state-by-state detail is available in KFF’s Medicaid Behavioral Health Services data collection. Further policy context is available in a series of behavioral health briefs that can be accessed in the “Behavioral Health Supplemental Survey” section on this page.

Medicaid coverage of behavioral health services varied moderately across states, with the median number of covered services at 44 of the 55 services queried (Figure 1). We provided state Medicaid officials with a list of 55 behavioral health benefits and asked them to indicate which were covered under their FFS Medicaid programs for adults, as of July 1, 2022 (for more information on survey methods, see Appendix A). We grouped the benefits queried by service category: institutional care/intensive, outpatient, SUD, naloxone (without prior authorization), crisis, integrated care, and other services. Notably, all but one state (SC) reported coverage of at least half of all services queried, with a median coverage rate of four-fifths of all services (44 of 55). These high rates of coverage reflect state trends in recent years to expand Medicaid services across the behavioral health care continuum—however, coverage of services may not translate into access to care, particularly given workforce shortages that make accessibility a challenge for Medicaid enrollees (as well as people with private insurance). We also asked states that reported coverage of each service to indicate any copay requirements as well as notable limits on the services (such as day limits or other utilization controls, including prior authorization requirements).1 Across services, most states reported no copay requirements, but limits were more common.

These findings are limited to FFS Medicaid and do not comprehensively capture variation in coverage for managed care organizations (MCOs) or Section 1115 waivers. Within each service category, we asked states to note differences in coverage for populations receiving services from MCOs or through Section 1115 waivers. Most states continue to rely on MCOs to deliver inpatient and outpatient behavioral health services, and these MCOs may offer services to their adult enrollees that differ from those available on a FFS basis. States also may use Section 1115 waivers to operate their Medicaid programs in ways that differ from what is required by federal statute; these can include “comprehensive” waivers that make broad changes in Medicaid benefits and other program rules or more targeted demonstrations. For state-specific information on behavioral health benefit coverage variation in MCOs or Section 1115 waivers as reported by states, see footnotes on indicators in the data collection. See also Appendix A for a summary of survey methods.

Across responding states, coverage rates were highest for SUD and outpatient services and lowest for crisis services (Figure 2). As indicated in Figure 2, for each service category, the majority of responding states covered more than 50% of the services queried, with at least a few states reporting coverage of 100% of services queried. Some states reported high coverage rates across service categories, including six states that cover more than 90% of all services queried: NY, AZ, OR, MI, NJ, and WV. Each of these states cover all services in multiple of the categories: for example, MI and OR each cover 100% of the services queried in the institutional, outpatient, SUD, and integrated care categories.2

Additional detail on definitions of and trends within each service category, including copays and limits, is included in the bullets below. For a detailed table showing the number of states with coverage of each individual benefit, see Appendix B.

- Institutional care and intensive services are typically reserved for situations that require a higher level of care and monitoring, such as behavioral health emergencies or long-term treatment for those with ongoing needs. Although a large majority of responding states report coverage of inpatient psychiatric hospital services and 23-hour observation, fewer than half of states report coverage of psychiatric residential treatment and adult group homes. Within this category, limits and copays are most common for psychiatric inpatient care, with more than one-third of covering states reporting limits and nearly one-fifth reporting copays. In states without Section 1115 waivers of the IMD payment exclusion, the number of psychiatric or residential care facilities that accept Medicaid may be restricted.

- Outpatient services include a wide range of psychiatric services provided in outpatient settings. Services in this category range from psychiatric testing—which may be used to inform diagnosis of mental health conditions—to more intensive services, like partial hospitalization services—a more intensive treatment that occurs multiple times a week on an outpatient basis. While all or nearly all states cover evaluation and testing services as well as individual, family, and group therapy, there is more variation in coverage of ADL/Skills training, case management, and day treatment services. Within this category, states were most likely to report limits for case management and copays for therapy (individual, family, or group).

- Services to treat SUD were queried in categories that follow the level of care criteria from the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM), ranging from early intervention to more intensive services, such as medically monitored intensive inpatient services (which may be subject to the IMD exclusion). Most states reported the highest coverage rates for SUD services compared to the other categories, likely bolstered by provisions in the SUPPORT Act. Within this category, nearly all states cover outpatient SUD treatment, while states were least likely to cover clinically managed high intensity residential services. As services grow in intensity, the number of states placing limits on the service also increases. Also within this service category, all or nearly all states reported coverage of medications for SUD treatment, including buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone. About one-third of states report limits for buprenorphine, but fewer limits are reported for naltrexone, which is not a controlled substance. For most SUD medications, about one-quarter of states report copay requirements (whereas fewer states report copays for services across the ASAM levels).

- We also asked states to report coverage of naloxone (without prior authorization requirements), which is used to reverse an opioid overdose and is prescribed to people with opioid use disorder, but may be available over the counter in the future. Nearly all states cover at least one formulation of naloxone without a prior authorization. A handful of states place other limits on these prescriptions and fewer than one-third of states require copays. (Data for this service category is not shown in Figure 2, but can be found in Appendix B.)

- Crisis services provide specialized responses to enrollees experiencing behavioral health emergencies. These services aim to reduce the reliance on law enforcement professionals, emergency departments, and other organizations staffed by people who are not behavioral health professionals. States were less likely to cover crisis services compared to other categories: for most states, crisis services was the category for which the state reported the lowest coverage rate, including several states that reported covering none of the crisis services queried. In contrast, four states (AZ, NM, NY, and TN) reported covering every crisis service queried. The wide range of coverage across states may reflect the emerging nature of crisis management in behavioral health. Within this category, states most frequently covered mobile crisis services (about three-quarters of responding states). This relatively higher coverage rate could be in part connected to the American Rescue Plan Act’sprovision of a new option and enhanced funding for states to provide community-based mobile crisis intervention services.

- Integrated care services provide behavioral health care in conjunction with physical health care. Examples include mental health screening in primary care settings and psychiatric evaluation with medical services. Traditionally, physical and behavioral health services have been delivered separately, but a growing body of evidence supports their integration. Coverage of services in this category varies; collaborative care model services are covered least frequently and psychiatric evaluations with medical services, as well as Medicaid individual/family counseling, are covered most often. For most integrated care services, few states reported copays, and limits were somewhat more common (fewer than one-fifth of states).

We also asked states to report coverage of a few additional behavioral health benefits in an “other” category. For example, more than four-fifths of responding states cover peer support services, which are provided by individuals who have personally experienced behavioral health challenges. These professionals may help enrollees with emotional support or navigation of health care or other social services. Peer supports has been identified as one method that states are using to extend the Medicaid behavioral health workforce.

Looking ahead, states may continue the trend of expanding Medicaid behavioral health benefits and may also enhance access to behavioral health care through other programs or policies. Since FY 2016, behavioral health benefits have been the most frequent category of service expansions reported on KFF’s annual Medicaid budget survey. For example, in FY 2022 and/or FY 2023, a number of states reported expanding coverage of crisis services and/or of services aimed to improve the integration of physical and behavioral health care. As access to behavioral health care is a key Medicaid priority at both the state and federal levels, these trends are likely to continue into the future. Notably, comprehensive coverage of behavioral health services has been linked to higher Medicaid acceptance rates by providers. In addition to further expanding coverage of behavioral health services, states may take additional policy actions to increase access and improve outcomes for enrollees with behavioral health conditions. For example, states may pursue initiatives to address behavioral health workforce shortages, such as by adopting permanent expansions of behavioral health telehealth policy to facilitate access to care. State Medicaid agencies may also play a role in developing, implementing, and helping to fund a statewide crisis system, including 988 crisis hotline services. KFF surveyed states on these and other behavioral health policies, with the results to be published in a series of briefs that can be accessed in the “Behavioral Health Supplemental Survey” section on this page. Finally, in addition to state Medicaid policy, federal legislation could continue to shape the behavioral health landscape for Medicaid enrollees.

This work was supported in part by Well Being Trust. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

This brief draws on work done under contract with Health Management Associates (HMA) consultants Angela Bergefurd, Gina Eckart, Kathleen Gifford, Roxanne Kennedy, Gina Lasky, and Lauren Niles.

Appendix A: Methodology

KFF contracted with Health Management Associates (HMA) to survey Medicaid directors in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to identify those behavioral health services covered for adult beneficiaries in their programs. The survey instrument captured information about services covered, copay requirements, and notable limits on those services as of July 1, 2022. The survey data is summarized in this brief and published on a state-by-state basis in KFF’s Medicaid Behavioral Health Services data collection. This data reflects what the states reported on the survey; responses vary in level of detail and were not verified through another source.

The survey asked states to report coverage of services in their fee-for-service (FFS) programs for categorically needy (CN) traditional Medicaid adults ages 21 and older. The survey did not ask about service coverage for medically needy (MN) coverage groups, which may differ from the state’s CN benefit package. Children were excluded from the survey because all children under age 21 enrolled in Medicaid through the categorically needy pathway are entitled to the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit, which requires states to cover all screening services for children as well as any services “necessary… to correct or ameliorate” a child’s physical or mental health condition (regardless of whether the service is covered for adults). All but six states (AR, DE, GA, MN, NH, UT) submitted survey responses, though in some instances a responding state may have left a particular service row blank. The territories are not included in the data.

We provided states with a list of 55 optional Medicaid behavioral health services. For each service, the state selected from a yes/no dropdown menu on the survey to indicate whether the service was covered. The list of behavioral health services included in this survey was based on the services queried by KFF in a similar 2018 survey; the 2018 data is available in the data collection. While we have posted data for both years, the data should not be compared across years as a trend due to changes in question phrasing over time.

Note that while this survey focused on coverage in FFS, most states continue to rely on MCOs to deliver inpatient and outpatient behavioral health services, and these MCOs may offer services to their adult enrollees that differ from those available on a FFS basis. States had an opportunity on the survey to note differences in required minimum benefits for MCOs, as well as differences in benefit coverage under Alternative Benefit Plans (benefit plans that Medicaid expansion states are required to design, in line with federal guidelines, for newly eligible ACA expansion adults) or Section 1115 waiver programs. To the extent that they were reported, these notes are included in the data collection as state-specific footnotes. However, the level of comprehensiveness of states’ responses in capturing these differences varies, and the level of information provided is likely inconsistent across states. Therefore, while the state-specific footnotes may provide useful context about coverage in an individual state, they should not be taken as a complete list of differences in benefit coverage under managed care, Alternative Benefit Plans, or Section 1115 waiver programs nationally.

Additional information on Medicaid coverage of behavioral health services is available here and here.

Appendix B: Summary Table

- Specifically, we asked states to describe any “notable limits on services or days or other utilization controls.” This question was open to state interpretation, so limits may not be consistently reported across states. ↩︎

- Also, NY covers all services in the crisis, SUD, and integrated care categories; AZ covers all services in the institutional, outpatient, crisis, and SUD categories; NJ covers all services in the institutional, outpatient, and integrated care categories; and WV covers all services in the outpatient and SUD categories. ↩︎

As State Medicaid Programs Prepare to Resume Disenrollments, Many States Are Using a Range of Strategies to Make it Easier for People Who Remain Eligible to Retain Coverage, But in Others it Will be More Difficult

Annual 50-State Survey Looks at Medicaid Eligibility, Enrollment, and Renewal Policies

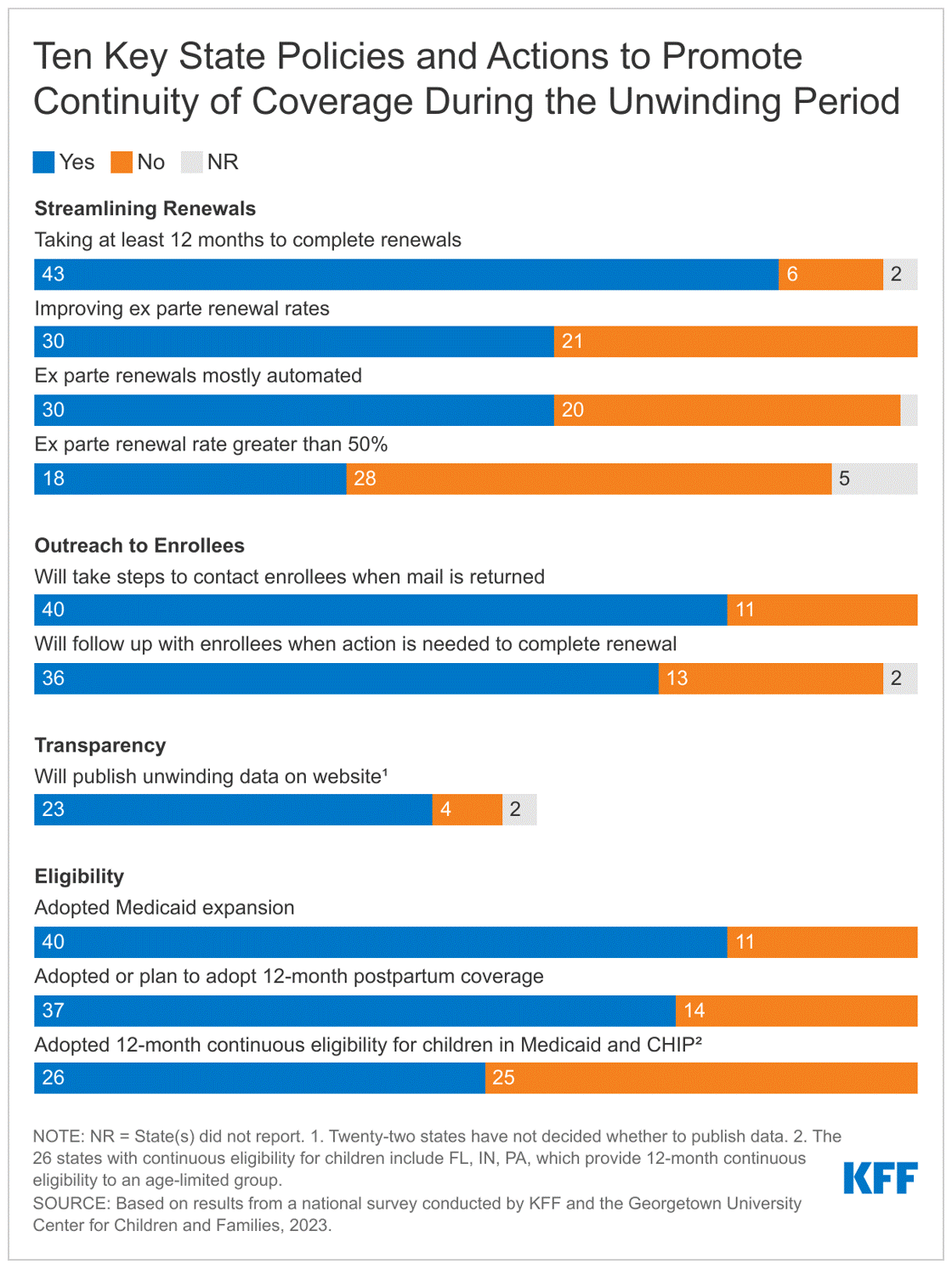

With pandemic-era protections for Medicaid enrollees set to expire this month, state Medicaid programs are gearing up to resume eligibility checks and disenrollments. But how the unwinding of the federal continuous enrollment provision affects enrollees and state budgets will vary according to states’ differing approaches and administrative capabilities, a new KFF survey finds.

The 21st annual KFF survey of state Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance (CHIP) Program officials finds that many states are using an array of strategies to promote continuity of coverage, while other states have adopted policies that may make it harder for people who are still eligible to retain coverage. Staffing shortages and systems limitations could also affect whether eligible enrollees are able to remain enrolled.

The survey, conducted by KFF in collaboration with the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, presents a snapshot of actions that states are taking to prepare for the unwinding of the provision that has paused Medicaid disenrollments since February 2020. It also highlights states’ Medicaid eligibility, enrollment, and renewal policies and procedures in place as of January 2023.

KFF has estimated that enrollment in Medicaid and CHIP will have grown by 23.3 million enrollees, to nearly 95 million, by the end of March when the continuous enrollment provision expires. Millions of beneficiaries are expected to be disenrolled over the next year, including some who are no longer eligible for Medicaid and others who still qualify but lose coverage due to administrative paperwork problems.

In the new survey, the one-third of states that were able to report projected coverage losses estimate that about 18 percent of Medicaid enrollees will be disenrolled after the continuous enrollment provision ends. The estimates range from seven percent to 33 percent of total enrollees and are consistent with other estimates that about 15 million people may lose Medicaid coverage over the coming year.

There is variation in the strategies states are adopting that could affect the amount of coverage losses, including:

- Taking 12-14 months to complete renewals following the end of the continuous enrollment provision (43 states). Taking more time can help prevent inappropriate terminations of those who are still eligible but could maintain enrollment of ineligible people for longer.

- Improving rates of renewals using ex parte processes that use reliable data sources — such as the Federal Data Services Hub and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) information — to verify ongoing eligibility, reducing the administrative burden on both states and enrollees (30 states).

- Contacting enrollees when renewal action is needed and following up with those who don’t respond (36 states). About half of the states (27) have been flagging individuals who may no longer be eligible or who did not respond to renewal requests.

- Adopting continuous eligibility policies for children, postpartum and for some adults that will help more people retain coverage during the unwinding. A total of 37 states have extended postpartum coverage to 12 months and 26 states provide 12-month continuous eligibility to some or all children in Medicaid and CHIP.

At the same time, some states have not adopted these strategies. Several states lack fully automated systems, processing some or most renewals manually (12 states) and others have ex parte renewal rates below 25 percent (11 states), which will increase the administrative burden on staff and enrollees. Even among states that adopt policies to promote continuity of coverage, implementation of policies and systems capacity will be key in how enrollees fare during the unwinding.

The challenge of processing an unprecedented volume of eligibility renewals and disenrollments comes at a time when most state Medicaid programs face significant staffing challenges. The survey finds that more than half of reporting states have staff vacancy rates greater than 10 percent for eligibility workers (16 of 26 reporting states) and slightly less than half for call center staff (13 of 28 reporting states).

These and other findings from the survey will be discussed today at a public web briefing. An archived video recording of the briefing will be available on kff.org later today.

The full survey report, “Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility and Enrollment Policies as States Prepare for the Unwinding of the Pandemic-Era Continuous Enrollment Provision,” includes state-level data about Medicaid and CHIP eligibility in every state. Also available are other recent KFF analyses related to the end of the continuous enrollment provision, including “Unwinding the Continuous Enrollment Provision: Perspectives from Current Medicaid Enrollees” and “Medicaid Enrollment Growth: Estimates by State and Eligibility Group Show Who may be at Risk as Continuous Enrollment Ends.

Annual Update of Key Health Data Collection by Race and Ethnicity, Now Including Mental Health Measures

The annual update of KFF’s collection of wide-ranging data on health and health care by race and ethnicity is now available, and this year includes measures on mental health care access, mental illness, substance use disorder, suicide rates, and drug overdose death rates.

The handy reference, “Key Data on Health and Health Care by Race and Ethnicity,” has nearly 50 charts and up to 70 data measures that highlight the scale and scope of disparities among six racial and ethnic groups in three broad categories: health coverage and access to and use of care; health status, outcomes, and behaviors; and social determinants of health.

When the measures are examined collectively to see how Asian, Hispanic, Black, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN), and Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) people fare compared to White people, readers can see the extent of disparities experienced by specific groups. For example, Black people fared worse than White people in 55 measures of health and health care and Hispanic people fared worse than White people in 44 of them. However, the data may mask disparities faced by subgroups within these broad racial and ethnic categories. For example, while Asian people fare the same or better than White people on many measures, certain ethnic subgroups of Asian people may fare worse. Further, ongoing data gaps and limitations hinder the ability to have a comprehensive understanding of the experiences of smaller groups, such as AIAN and NHOPI people.

The overview of how specific racial/ethnic groups fared compared to White people is a gateway to explore the detailed findings, some of which have received attention or policy action recently:

- Among adults with any mental illness, Black (39%), Hispanic (36%), and Asian (25%) adults were less likely than White (52%) adults to receive mental health services as of 2021.

- 2020 data reflect that AIAN people had the highest rates of drug overdose deaths compared with all other racial and ethnic groups. Drug overdose death rates among Black people exceeded rates for White people as of 2020, reflecting larger increases among Black people in recent years.

- Although Black people did not have higher cancer incidence rates than White people overall and across most types of cancer that were examined, they were more likely to die from cancer.

- At birth, AIAN and Black people had a shorter life expectancy compared to White people as of 2021, and AIAN, Hispanic, and Black people experienced larger declines in life expectancy than White people between 2019 and 2021. These life expectancy trends may matter in any discussion of increasing the age of eligibility for Medicare.

- Black infants were more than two times as likely to die as White infants, and AIAN infants were nearly twice as likely to die as White infants as of 2021. Black and AIAN women also had the highest rates of pregnancy-related mortality.

The Estimated Value of Tax Exemption for Nonprofit Hospitals Was About $28 Billion in 2020

Editor’s note: This analysis was revised on March 27, 2023 to account for data anomalies and incorporate corrections, including to our estimate of the value of property tax exemption. These corrections result in a modest increase in the total estimated value of tax exemption, from $27.6 to $28.1 billion.

Over the years, some policymakers have questioned whether nonprofit hospitals—which account for nearly three-fifths (58%) of community hospitals—provide sufficient benefit to their communities to justify their exemption from federal, state, and local taxes. This issue has been the subject of renewed interest in light of reports of nonprofit hospitals taking aggressive steps to collect unpaid medical bills, including suing patients over unpaid medical debt, including patients who are likely eligible for financial assistance. Further, recent research indicates that nonprofit hospitals devote a similar or smaller share of their operating expenses to charity care in comparison to for-profit hospitals. In light of these concerns, several policy ideas have been floated to better align the level of community benefits provided by nonprofit hospitals with the value of their tax exemption.

This data note provides an estimate of the value of tax exemption for nonprofit facilities based on hospital cost reports, filings with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and American Hospital Association (AHA) survey data (see Methods for additional details). We define the value of tax exemption as the benefit of not having to pay federal and state corporate income taxes, typically not having to pay state and local sales taxes and local property taxes, and any increases in charitable contributions and decreases in bond interest rate payments that might arise due to receiving tax-exempt status. (For additional information, see Methods.)

Results

The total estimated value of tax exemption for nonprofit hospitals was about $28 billion in 2020 (Figure 1). This represented over two-fifths (44%) of net income (i.e., revenues minus expenses) earned by nonprofit facilities in that year. To put the value of tax exemption in perspective, our estimate is similar to the total value of Medicare and Medicaid disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments in the same year ($31.9 billion in fiscal year 2020) (i.e., supplemental payments to hospitals that care for a disproportionate share of low-income patients which are intended, in part, to offset the costs of charity care and other uncompensated care).

The estimated value of federal tax-exempt status was $14.4 billion in 2020, which represents about half (51%) of the total value of tax exemption. This is primarily due to the estimated value of not having to pay federal corporate income taxes ($10.3 billion). In addition, we assumed that individuals contribute more to tax-exempt hospitals because they can deduct donations from their income tax base ($2.5 billion) and issue bonds at lower interest rates because the interest is not taxed ($1.6 billion). Our estimates of changes in charitable contributions and interest rates on bonds only account for federal tax rates for simplicity and may therefore understate the total value of tax exemption because they do not account for the effects of state taxes.

The total estimated value of state and local tax-exempt status was $13.7 billion in 2020, which represents about half (49%) of the total value of tax exemption. This amount includes the estimated value of not having to pay state or local sales taxes ($5.7 billion), local property taxes ($5.0 billion) or state corporate income taxes ($3.0 billion).

The total estimated value of tax exemption (about $28 billion) exceeded total estimated charity care costs ($16 billion) among nonprofit hospitals in 2020 (Figure 2), though charity care represents only a portion of the community benefits reported by these facilities. Hospital charity care programs provide free or discounted services to eligible patients who are unable to afford their care and represent one of several different types of community benefits reported by hospitals. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) also defines community benefits to include unreimbursed Medicaid expenses, unreimbursed health professions education, and subsidized health services that are not means-tested, among other activities. One study estimated that the value of tax exemption exceeded the value of community benefits broadly for about one-fifth (19%) of nonprofit hospitals during 2011-2018 or about two-fifths (39%) when considering the incremental value of community benefits provided relative to for-profit facilities. Other research suggests that nonprofit hospitals devote a similar or smaller share of their operating expenses to charity care and unreimbursed Medicaid costs—which accounted for most of the value of community benefits in 2017—when compared to for-profit hospitals.

The value of tax exemption grew from about $19 billion in 2011 to about $28 billion in 2020, representing a 45 percent increase (Figure 3). The value of tax exemption increased in most of the years (7 out of 9) in our analysis, though there was a notable decrease of $5.8 billion in 2018. The largest single-year increase was $4.1 billion in 2020. The large decrease in the value of tax exemption in 2018 coincided with the implementation of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which permanently reduced the federal corporate income tax rate from 35 to 21 percent and therefore decreased the value of being exempt from federal income taxes.

The large increase in the value of tax exemption in 2020 overlapped with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This increase primarily reflects a large increase in aggregate net income for nonprofit hospitals in 2020. Although there were disruptions in hospital operations in 2020, hospitals received substantial amounts of government relief, and it is possible that other sources of revenue, such as from investment income, may have also increased. Increases in net income in turn increased the value of not having to pay federal and state income taxes.

Increases in the estimated value of tax exemption over time also reflect net income growth that preceded the pandemic as well as increases in estimated property values, supply expenses, and charitable contributions, each of which would carry tax implications if hospitals lost their tax-exempt status (e.g., with some supply expenses being subject to sales taxes). Even when setting aside the strong financial performance of nonprofit hospitals in 2020 as a potential outlier, total net income among nonprofit facilities increased substantially in the preceding years, before increasing further in 2020. Although we are not able to directly observe the value of the real estate owned by hospitals, the estimated value of exemption from local property taxes—which is based on our analysis of property taxes paid by for-profit hospitals—increased by 63 percent from 2011 to 2019. Finally, the supply expenses in our analysis increased by 44 percent and charitable contributions increased by 49 percent from 2011 to 2019.

Discussion

The estimated value of tax exemption for nonprofit hospitals increased from about $19 billion in 2011 to about $28 billion in 2020. The rising value of tax exemption means that federal, state, and local governments have been forgoing increasing amounts of revenue over time to provide tax benefits to nonprofit hospitals, crowding out other uses of those funds. This has raised questions about whether nonprofit facilities provide sufficient benefit to their communities to justify this tax benefit. Federal regulations require, among other things, that nonprofit hospitals provide some level of charity care and other community benefits as a condition of receiving tax-exempt status. However, a 2020 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report raised questions about whether the government has adequately enforced this requirement. Further, some argue that the federal definition of “community benefits” is too broad—e.g., by including medical training and research that could benefit hospitals directly—though others believe that the definition is too narrow. Most states have additional community benefit requirements for nonprofit or broader groups of hospitals—such as providing charity care to patients below a specified income threshold—though there is little information about the effectiveness of these regulations or the extent to which they are enforced.

Several policy ideas have been floated at the federal and state level that would increase the regulation of community benefits spending among nonprofit hospitals or among hospitals more generally. These include proposals to create or expand state requirements that hospitals provide charity care to patients below a specified income threshold, mandate that nonprofit hospitals provide a minimum amount of community benefits, establish a floor-and-trade system where hospitals would be required to either provide a minimum amount of charity care or subsidize other hospitals that do so, create mechanisms to increase the uptake of charity care, expand oversight and enforcement of community benefit requirements, replace current tax benefits with a subsidy that is tied to the value of community benefits provided, and introduce reforms intended to better align community benefits with local or regional needs. These policy options would inevitably involve tradeoffs. While they may expand the provision of certain community benefits, hospitals would incur new costs as a result, which could in turn have implications for what services they offer, how much they charge commercially insured patients, and how much they invest in the quality of care.

Methods

Our analysis defined the value of tax exemption as the benefit of not having to pay federal or state corporate income taxes, typically not having to pay state and local sales taxes and local property taxes, and any increases in charitable contributions and decreases in bond interest rate payments that might arise due to receiving tax-exempt status. To estimate the value of these benefits, we drew on methods from three studies and a report commissioned by the American Hospital Association (AHA). As is the case with prior work, we assumed that nonprofit hospitals and health systems would take various allowed deductions if they were required to pay taxes, but we do not capture all nuances of the tax code, nor do we model any other actions that hospitals take to reduce their tax burden, such as by changing how they operate or changing how they account for revenues and expenses. Two of the studies that we draw from estimated the total value of tax exemption or of federal tax exemption. Our estimates are smaller than these amounts, which likely reflects aspects of our approach that are more conservative than these papers. We detail our specific approach for each component below.

As a starting point, we relied on RAND Hospital Data, which applies cleaning and processing steps to annual cost report data submitted by hospitals to the Healthcare Cost Report Information System (HCRIS). Every Medicare-certified hospital must submit a cost report to a Medicare Administrative Contractor (MAC) under contract with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), meaning that HCRIS pulls data from all US hospitals except federal hospitals and some children’s hospitals. We used the calendar year version of RAND Hospital Data, which apportions data from different cost reports for hospitals that do not use a calendar year reporting period. For example, 2019 data reflect the weighted average of hospital finances during various periods from 2018 through 2020 (i.e., both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) for a subset of hospitals. We excluded hospitals in the U.S. Territories and hospitals that did not report positive operating expenses in a given year (about 0.3% of remaining hospitals). We also relied on the AHA Annual Survey Database and IRS Form 990 data, focusing on hospitals and systems that we were able to match to RAND Hospital Data. We imputed values for supply expenses, charitable contributions, and tax-exempt bonds in instances where data were missing or unavailable for a given hospital or health system or year. We did not attempt to impute net income when missing (about 1.0% of remaining hospitals).

Federal corporate income tax. We estimated the federal corporate income tax that a given nonprofit hospital or health system would have to pay without the tax exemption by multiplying an estimate of taxable income by the federal corporate income tax rate, which was 35 percent from 2011 through 2017 but decreased to 21 percent in 2018. Our estimate of taxable income reflects the difference between revenues and expenses, accounting for deductions allowed under the federal tax code for interest rate payments, state corporate income taxes, state and local sales taxes, and local property taxes and adjusting for estimated changes in charitable contributions and bond interest rate payments. Hospitals may report unrealized gains or losses on financial instruments, which do not affect their tax base, as part of their net income. We aggregated hospital level data to the system level, as applicable, before estimating tax benefits. Aggregate estimates of tax benefits are lower when calculated at the system versus hospital level, as systems may be able to offset taxable profits from one system member with losses from another. We also modeled options for businesses to offset taxable income with losses in earlier and later years. Other studies have used an alternative approach that multiplies net income by estimates of effective tax rates based on tax filings from for-profit hospitals, nursing homes, and residential care facilities. Using this approach would have increased our estimates by $3.6 billion. We chose our approach because it is more closely tied to financial data from nonprofit hospitals.

State corporate income tax. We estimated the state corporate income tax that a given nonprofit hospital or health system would have to pay without tax exemption by multiplying an estimate of their taxable income in a given state by the state corporate income tax rate. We used a similar approach to estimating taxable income as above, except that we did not deduct the state corporate income tax (by definition) and we did not allow entities to offset taxable income with losses from later years, in line with state law. We obtained state corporate income tax rates by year from the Tax Foundation.

State and local sales taxes. We estimated the state and local sales taxes that a given nonprofit hospital or health system would have to pay without tax exemption by multiplying their total non-pharmaceutical supply expenses (or, for a system, the total supply expenses among member hospitals in a given state) by the average state and local sales tax rate in that state. We obtained total non-pharmaceutical supply expenses from the AHA Annual Survey Database. We obtained average state and local tax rates by state and year from the Tax Foundation.

Property taxes. We estimated the local property taxes that a given nonprofit hospital would have to pay without the tax exemption based on the amount paid by for-profit hospitals that reported this information. In the small number of states with five or more for-profit hospitals, we calculated the median ratio of property taxes to operating expenses among for-profit hospitals for a given state and year and then multiplied this amount by the operating expenses for a given nonprofit hospital. In states with fewer than five for-profit hospitals, we instead relied on the national median ratio among for-profit hospitals.

Charitable contributions. If nonprofit hospitals were no longer tax-exempt, donors who take itemized deductions for income taxes would no longer be able to deduct their contributions. We assumed that donors would decrease their contributions by an amount equal to their tax increase. We estimated this amount by multiplying charitable contributions by the estimated average household marginal tax rate of donors to health care organizations (32% from 2011 to 2017 and 23% from 2018 to 2020). Our 2011 to 2017 estimate of the marginal tax rate comes from a previous study. We updated this amount for 2018 to 2020 based on a Tax Policy Center estimate of the decrease in the average effective marginal tax rate for all donors in 2018 as a result of changes to the tax code. We estimated charitable contributions from Internal Service Revenue (IRS) Form 990 data by subtracting government grants and in-kind contributions from total contributions, gifts, grants, and other related amounts.

Bond interest rate payments. We assumed that, if interest rate payments from hospitals to bondholders were taxed, issuers would increase interest rates accordingly. We estimated the difference between taxable and non-taxable interest rates by: (1) estimating the average taxable interest rate using a rolling average of the Moody’s Seasoned Aaa and Baa index over the previous 10 years, (2) assuming a marginal tax rate for investors of 24 percent (based on a Capital Group post suggesting that municipal bonds are a better investment than taxable bonds for individuals with a marginal tax rate of 24% or higher), (3) assuming that average bond interest rates for nonprofit hospitals are equal to the after-tax bond interest rates among for-profit hospitals (so that investors are indifferent between the two), and (4) taking the difference. To estimate the value to a given hospital of paying lower interest rates, we multiplied the difference by the total value of tax-exempt bonds issued, which we obtained from IRS Form 990 data.

We used RAND Hospital Data to estimate charity care costs in 2020 based on amounts reported by the hospitals in our tax exemption analysis. HCRIS instructions indicate that hospitals should report amounts related to both their charity care and uninsured discounts as part of their charity care costs. After cleaning these data, we imputed values in instances where data were missing.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Nonprofit Hospitals’ Tax-Exempt Status Worth About $28 Billion, New KFF Analysis Finds

Editor’s Note: The press release was updated on March 27, 2023, to reflect corrections in the underlying analysis, resulting in a modest increase in the total estimated value of tax exemption, from $27.6 to $28.1 billion.

The tax-exempt status of the nation’s nonprofit hospitals collectively was worth about $28 billion in 2020, a new KFF analysis of hospital financial data estimates.

The total reflects the estimated federal, state and local taxes that nonprofit hospitals do not have to pay. It also includes estimated increases in charitable contributions and decreases in bond interest rate payments due to hospitals having tax-exempt status.

Nearly three-fifths of the nation’s community hospitals are nonprofits, an Internal Revenue Service designation that requires hospitals to provide charity care and other benefits to their communities in exchange for federal tax-exempt status.

The $28 billion total is much higher than the $16 billion in free or discounted services provided by nonprofit hospitals in 2020 through their charity care programs, though charity care is just one element of the community benefits nonprofit hospitals provide. Other community benefits include unreimbursed expenses related to Medicaid and health professional education, and certain subsidized health services.

“The Estimated Value of Tax Exemption for Nonprofit Hospitals Was About $28 Billion in 2020” is available as part of KFF’s expanding work examining the business practices of hospitals and other providers, and their impact on costs and affordability.

Challenges to the FDA’s Approval of Medication Abortion Pills Could Curtail Access Throughout the United States

In anticipation of a ruling in a case with enormous implications for access to medication abortion in the United States, a new KFF brief explains the impact of this case, and others filed in federal courts, involving the FDA’s regulation of medication abortion. The case that has gotten the most attention recently is Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM) v. FDA, filed in November 2022, a challenge to the FDA’s decision to approve mifepristone (the first medication taken as part of the medication abortion drug regimen) and to include misoprostol in the medication abortion regimen. The outcome of AHM v. FDA, along with the other challenges, could have ramifications for access to medication abortion throughout the country, including in states where abortion is legal and protected. The outcome could also potentially have broader implications for the FDA’s authority in regulating drugs.

Read the brief, “Legal Challenges to the FDA Approval of Medication Abortion Pills,” which focuses on the major claims in the AHM case. Many of the issues raised in the brief will also be relevant to the other abortion cases involving the FDA and its role in approving and regulating mifepristone.

As Congress Considers Reauthorizing PEPFAR, A New Policy Watch Asks and Answers Fundamental Questions

As Congress considers reauthorizing the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) for a fourth time, a new KFF Policy Watch details key facts about the program and top issues related to its authorization and funding. Created in 2003 as the U.S. government’s signature global health effort in the fight against HIV, PEPFAR is broadly regarded as one of the most successful programs in global health history, with the U.S. government reporting tens of millions of lives saved over the past 20 years. However, the reauthorization comes in a period of heightened debate over the federal budget in a divided Congress.

The Policy Watch asks and answers frequently asked, fundamental questions about PEPFAR’s reauthorization, including:

• Will PEPFAR end without reauthorization?

• Are there any provisions of the program that would end without reauthorization?

• Is PEPFAR reauthorization required for the program to receive continued funding?

• What are some issues to consider for PEPFAR’s future, and are these affected by reauthorization?

Read “PEPFAR Reauthorization 2023: Key Issues” and access a variety of resources about the program in our PEPFAR Policy Resource Hub

Legal Challenges to the FDA Approval of Medication Abortion Pills

Key Findings

On June 13, 2024, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM) v. FDA that the AHM does not have standing to sue the FDA for injury. However, three state Attorneys’ Generals have intervened in this case in district court, and it is unclear how this action will shape the case when it goes back to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals and then back to the originating federal district court.

Medication abortion has emerged as a major legal front in the battle over abortion access across the nation. Since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs ruling on June 24, 2022, four new cases have been filed in federal courts specifically regarding aspects of the FDA’s regulation of medication abortion. These challenges, some in the early stages, could affect the availability of abortion medications in the short and long term. At the heart of these cases is the FDA’s authority to approve drugs, whether courts can reverse the FDA’s decisions, and if states can impose additional restrictions beyond what the FDA requires. The case that has gotten the most attention recently is Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (AHM) v. FDA, filed in November 2022, a challenge to the FDA’s decision to approve mifepristone, the first medication taken as part of the medication abortion drug regimen and to include misoprostol in the medication abortion regimen. The plaintiffs in this case contend the FDA did not act within its authority and that an 1873 anti-obscenity law, the Comstock Act, prohibits the mailing of any medication used for abortion.

The outcome of this case could have ramifications for access to medication abortion throughout the country, including in states where abortion is legal and protected. For the first time, the court is being asked to essentially overturn the approval of a drug, in this case one that has been safely used by more than 5.6 million people since it was approved in 2000 with a long record of safety and effectiveness. This issue brief focuses on the major claims in the AHM case, as a decision is expected soon, but many of the issues raised will also be relevant to the other abortion cases involving the FDA and its role in approving and regulating mifepristone.

Background on the FDA’s approval of Mifepristone

Mifepristone, often referred to as medication abortion pills, RU-486, or the abortion pill, was approved by the FDA over 20 years ago as a medication that can safely and effectively end pregnancy. A regimen of mifepristone, followed by misoprostol, a drug that is also used to treat ulcers, manage miscarriages, induce labor, and assist with IUD insertions, is an FDA approved protocol for abortion during the first 70 days, or up to 10 weeks, after the first day of the pregnant person’s last menstrual period. It is estimated that in 2020, medication abortions accounted for just over half of all abortions in the US. The drug regimen terminates pregnancies successfully 99.6% of the time, with a 0.4% risk of major complications, and an associated mortality rate of less than 0.001 percent (0.00064%). The FDA initially approved mifepristone with some conditions on who and how it can be dispensed in 2000, and over the years the FDA has amended these restrictions. (Appendix Table 1). The plaintiffs in the AHM case are challenging the FDA’s initial approval of mifepristone on procedural grounds, as well as the 2016, 2019 and 2021 changes to the drug’s safety program as being beyond the FDA’s authority.

Subpart H

When the FDA initially approved mifepristone, it did so under a provision called “Subpart H,” a set of regulations implemented to expedite the approval of “new drug products that have been studied for their safety and effectiveness in treating serious or life-threatening illnesses,” like those to used treat HIV. The FDA approval process for mifepristone, however, was not expedited, as it was approved more than four years after the original application was filed. In the case of mifepristone, Subpart H was originally used to restrict the dispensing to prescribers who agreed to dispense it in certain health care settings, by or under the supervision of a qualified physician who attested to the ability to accurately date pregnancies and diagnose ectopic pregnancies. The drug was not available for distribution at retail pharmacies.

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy

The FDA Amendments Act of 2007 (FDAAA) added a new section (Section 505-1) to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) authorizing the FDA to require a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) for a drug if the FDA deems it is necessary to ensure that the drug’s benefits outweigh its risks; it also revises the terminology for eligibility for the drug from treating a “serious or life threatening illness” to permitting the FDA to require a REMS for drugs intended to be used for a “disease or “condition.”

Congress also deemed all drugs with existing restricted-distribution programs (Section 909 of the FDAAA), including mifepristone, to require a REMS. Congress required sponsors of such “deemed” drugs to submit a proposed REMS to the FDA — which mifepristone’s sponsor did. The FDA approved the initial REMS for mifepristone in 2011, which required in-person dispensing by or under supervision of a certified physician, the dispensing of misoprostol at the provider’s office or clinic, and a follow-up visit 14 days later. In 2016, the FDA updated and approved a new evidence-based regimen and drug label for mifepristone. This updated regimen expanded the use of the mifepristone/misoprostol regimen from 49 days to up to 70 days (10 weeks) of pregnancy. In addition, the provider certification requirement was broadened from being limited to physicians only to include other advanced practice clinicians (e.g., nurse practitioners and physician assistants) who can meet the REMS requirements. The FDA approved the generic version of mifepristone in 2019 and issued a unified REMS for both the generic and the brand-name medication. In April 2021, the FDA decided to exercise enforcement discretion for the in-person dispensing requirement during the public health emergency. In December 2021, when the FDA rejected the plaintiffs’ citizen petition, the FDA removed the in-person dispensing requirement for mifepristone and expanded the distribution to include certified pharmacies in addition to certified clinicians. On January 3, 2023, the FDA updated the REMS approving the protocol for certification of pharmacies, allowing those that have been certified by the manufacturers to dispense mifepristone directly to patients (eliminating the requirement that it can only be dispensed directly to the patient by the certified provider).

The Legal Challenge to the FDA’s Approval of Mifepristone

In the case, Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA, (filed November 18, 2022 in the US District Court for The Northern District of Texas Amarillo Division presided over by a Trump Administration appointed judge), the plaintiffs are challenging the FDA’s approval of mifepristone on many grounds. (Table 1) The plaintiffs are the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine (a newly formed anti-abortion advocacy coalition); the American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists; the American College of Pediatricians; and the Christian Medical and Dental Associations, as well as three individual doctors (Shaun Jester, D.O., Regina Frost-Clark, M.D., Tyler Johnson, D.O., and George Delgado, M.D.)

As with any lawsuit, the plaintiffs first need to show they have legal standing by demonstrating they have an injury, and that they have filed this action within six years of the FDA’s action, the statute of limitations.

Do the plaintiffs have standing?

The plaintiffs, the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, the AAPLOG, the American College of Pediatricians and the Christian Medical & Dental Associations, contend that they have members in Texas and around the country who have treated and will continue to treat women and girls who have experienced a complication from medication abortion. In addition, the associations assert that they have suffered organizational harms from the FDA’s approval of mifepristone because they have spent time and resources to conduct their own studies and analysis, and to educate their members about the dangers of medication abortion. Anyone challenging the actions of a federal agency must demonstrate that they are within the “zone of interests” protected or regulated by the statute in question. The plaintiffs contend that they are within the FDCA’s zone of interests, meaning their interests are protected by the statute. The plaintiffs who are individual doctors are suing on their own behalf and on behalf of their patients, citing that the Supreme Court has held that medical providers have third-party standing to invoke the rights on their patients. Interestingly, in his dissenting opinion for June Medical Services v. Russo, Justice Alito called into question the precedent that allowed abortion providers to challenge abortion restrictions on behalf of their patients.

The Government argues that none of the plaintiffs have established an injury-in-fact or that they are within the “zones of interest,” which is necessary to establish standing. While the plaintiffs are not regulated by the FDA and do not prescribe mifepristone, the plaintiffs claim they will have to treat patients who suffer from complications from mifepristone and therefore have less time and resources to treat other patients. The Government argues this reasoning is speculative. Furthermore, they claim this approach to standing could open the door for any doctor to challenge the FDA’s approval of any drug that causes adverse events.

Have the plaintiffs filed this lawsuit within the statute of limitations?

There is a six-year statute of limitation to challenge any federal agency action. Anyone challenging an agency action is also required to exhaust their administrative remedies before initiating litigation seeking judicial review. FDA regulations specifically require challengers to file a “citizen petition” before any legal action can be filed in a court. In 2019 the plaintiffs filed a citizen petition asking the FDA to undo a 2016 revision of the REMS for mifepristone, which had changed the gestational limit for taking the drugs from 49 days to 70 days (10 weeks), expanded the provider certification requirement beyond physicians to include advance practice clinicians (e.g. nurse practitioners and physician assistants), and eliminated the requirements for in-person administration of misoprostol and for an in-person follow-up examination. The Government’s position is that the statute of limitations bars the plaintiffs from raising any issues not included in their 2019 citizen petition. This petition did not contest the underlying approval of mifepristone established in 2000. The plaintiffs maintain that the statute of limitations resets every time the FDA has modified the restrictions for mifepristone.

WHAT ARE THE PLAINTIFFS’ CLAIMS?

If the plaintiffs make it through these two hurdles, they are challenging the FDA’s approval and subsequent modifications of the dispensing requirements for mifepristone as being beyond the FDA’s authority based on the FFDCA statute. The plaintiffs are asking the court to find the FDA acted beyond its authority to initially approve mifepristone using Subpart H and that the FDA’s initial approval and subsequent actions to regulate mifepristone were not supported by sufficient evidence of safety and efficacy. The plaintiffs have cited their own studies to reach their conclusion that mifepristone is not safe. It is an unprecedented request to ask a court to block the FDA’s prior determination that a drug is safe and effective (Table 1).

| Table 1: Summary of the Plaintiffs’ and the Government’s Positions Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA | |

| Claim: FDA’s approval of mifepristone in 2000 violated the Administrative Procedures Act (APA) because the FDA Lacked the authority to use subpart H | |

Plaintiffs’ Position:

| Government’s Position:

|

| Claim: The FDA’s approval of and subsequent actions to regulate mifepristone were not supported by sufficient evidence of safety and efficacy and did not meet federal pediatric assessment requirements, violating the APA and Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act | |

Plaintiffs’ Position:

| Government’s Position:

|

| Claim: The FDA’s approval of mifepristone and subsequent modifications violated the Comstock Act. | |

Plaintiffs’ Position:

| Government’s Position:

|

Does the Comstock Act impede the distribution of abortion medications?

When the Comstock Act was passed in 1873, it made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious,” “immoral” or “indecent” publications or other materials through the mail. It also banned the mailing of any articles that could be used as contraceptive or to cause abortions. The plaintiffs in this case contend that the Comstock Act should be read literally. The plaintiffs cite a section of the Act as prohibiting the mailing or delivery by any letter carrier of “[e]very article or thing designed, adapted, or intended for producing abortion” and “[e]very article, instrument, substance, drug, medicine, or thing, which is advertised or described in a manner calculated to lead to another to use or apply it for producing abortion, ” and a separate section as prohibiting the use of “any express company or other common carrier” to transport abortion drugs in interstate or through foreign commerce. They are seeking to block the distribution of drugs for abortion (mifepristone and misoprostol) to clinics, doctors, and hospitals, as well as to patients, on grounds that the Comstock law makes it illegal to send these through the mail or other carriers.

However, the Government contends that because the plaintiffs failed to raise the Comstock argument at any stage of the administrative proceedings, they are therefore barred from raising it now. In addition, the Government contends that the plaintiffs’ Comstock argument fails on the merits. Although Congress has not amended the abortion provisions in the statute, prior court cases and administrative actions have limited the reach of the Comstock Act. In December 2022, the US Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel issued an opinion, concluding that the Comstock Act does not prevent the mailing of medication for abortion for legal use.

Possible Rulings and Implications

Depending on the ruling, the case could affect the availability and distribution of mifepristone. More broadly, if the court allows the plaintiffs to have standing, the door may be opened for future litigation brought by doctors and organizations challenging the FDA’s approval of other drugs. Similarly, if the court does not restrict the plaintiffs’ challenges to what they included in their 2019 citizen petition, then other litigation may be brought beyond the six years statute of limitation period that challenges agencies’ actions without first exhausting administrative remedies.

Possible Ruling 1: FDA Approval of Mifepristone Violated the APA

The federal court could find that the FDA did not apply a lawful review process for its initial approval of mifepristone in 2000. It would be unprecedented for a Court to rule that the FDA did not properly approve a drug, much less one that has a safety and effectiveness record over more than two decades. While the availability of mifepristone for abortion could be blocked following such a ruling, it is likely, based on the research, record and clinical trials, that the drug would be reapproved by the FDA. This would, however, force those who seek abortion to use a less effective medication abortion protocol with misoprostol only in the interim. The court could also rule that the FDA acted beyond its authority by including misoprostol in the two-drug regimen for medication abortion. However, because misoprostol is currently used for medication abortion off-label, it is not clear how this ruling would impact the availability of misoprostol.

If the court suspends the FDA’s approval of mifepristone, with or without finding that the FDA acted improperly by including misoprostol, clinics will likely respond by switching to using a higher dose of misoprostol alone, but that is less effective (estimated to be between 80% and 100% effective) than using mifepristone and misoprostol together (99% effective). Misoprostol along can also cause more side effects, including pain and bleeding than the combination regimen. In addition, patients experiencing a miscarriage will also need to switch to using only misoprostol. This ruling will likely have implications far beyond abortion. This action would open the door for other actors to potentially sue to block the approval of existing or new drugs that may be deemed as controversial such as vaccines or treatments for conditions that are at the crosshairs of culture wars. Manufacturers may be reluctant to bring to market certain new drugs or treatments if they are concerned that a court ruling could block the approval of the drug in the future.

Possible Ruling 2: FDA 2016 Revision of the REMS Violated the APA

The court could limit the plaintiffs’ arguments to those they included in their 2019 citizen petition, which challenged changes to the conditions of use and restrictions on the distribution of mifepristone. The 2019 petition asked the FDA to “[r]etain” the 2011 REMS and its in-person dispensing requirement, and to “restore and strengthen elements of the [mifepristone] regimen and prescriber requirements approved in 2000” to: (1) limit mifepristone’s use to 49 days gestation; (2) require the drug to be administered by or under the supervision of a physically present and certified physician who has ruled out ectopic pregnancy; (3) require three office visits; (4) include a contraindication for patients who do not have convenient access to emergency medical care; (5) require reporting of certain adverse events to FDA; and (6) require additional studies If the court grants the plaintiffs’ request to roll back the requirements for the gestational age for which the regimen is approved and limit the pool of clinicians who could be certified to dispense the drug therefore constraining abortion access for those in states that have not banned abortion. This would effectively eliminate the new evidence-based protocols the FDA has established which removed the in-person dispensing requirement, permitted telehealth abortions, and established the process for pharmacies to become certified to dispense mifepristone.

Possible Ruling 3: The Comstock Act Blocks Distribution of Medication Abortion Pills

If the court rules in favor of the plaintiffs finding that the Comstock Act prohibits the mailing of mifepristone and misoprostol, the distribution channels for both drugs could be effectively shut down, and access to the drugs will become limited over time. This would affect not only the mailing of the drug to patients through telemedicine but could also limit the distribution of the medication to hospitals, clinics or clinicians. Misoprostol is used to treat ulcers, and mifepristone is used to treat Cushing’s Syndrome. Both drugs are used for miscarriage management. Patients who need these drugs ,for these conditions, many of whom are women, could potentially have limited or no access. If the court ruling relies narrowly on the Comstock Act, there would not likely be broader ramifications for the FDA’s authority to regulate other drugs and be limited to medication abortion. It is conceivable that if it reaches the Supreme Court on appeal, the Court could leave intact the FDA’s current authority to review and approve drugs, but rule in favor of the plaintiffs, based on the Comstock Act reasoning that it’s the responsibility of Congress, not the Court’s, to repeal the Comstock Act if it’s no longer valid. This ruling could create large barriers for patients to access medication abortion across the country, even in states where abortion is legal. Even if the ruling does not find that the FDA’s approval of mifepristone was improper, a ruling based on the Comstock Act would severely limit distribution of the mifepristone and misoprostol.

Other Cases Involving the FDA and Medication Abortion

While many have focused on the AHM case, there are several other cases in the federal court system that relate to aspects of the FDA’s regulation of mifepristone. Now that states are permitted to ban abortion, new questions have arisen regarding the intersection of federal and state authority when it impacts access to abortion.

Federal law preempts state law, but some are questioning how the new state authority to regulate or ban abortion intersects with the Federal FDA’s authority to regulate drugs. There are currently two cases in federal court challenging state abortion prohibitions and restrictions on federal preemption grounds. The maker of a generic mifepristone medication, GenBioPro, Inc., is challenging West Virginia’s total abortion ban, and an ob-gyn, Dr. Amy Bryant, is challenging the abortion restrictions in North Carolina, which include requirements that mifepristone be dispensed in person by a physician following a state-mandated counseling session and a 72-hour waiting period. In both cases, plaintiffs argue that the FDA’s authorization and regulation of mifepristone preempt state law banning the use of the medication or regulating its use more strictly, and given this, enforcement of the state laws should be blocked. If these lawsuits are successful, people living in states where abortion is banned could access medication abortion.

In addition, the Oregon and Washington Attorneys General joined by 10 other Attorneys General are also challenging the FDA’s decision-making about mifepristone. but rather than challenging the FDA approval process, the plaintiffs are calling to question the FDA’s decision to impose restrictions on prescribing and dispensing mifepristone through the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation System (REMS). The case filed by the Oregon and Washington Attorneys General in the US District Court in the Eastern District of Washington could result in a conflicting ruling from the AHM case. Ultimately, the Supreme Court could decide the role of the courts to review the FDA’s decisions, and how much deference the agency should be given.

Conclusion

No matter how the district court rules in the AHM case, the parties will likely appeal to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals and then to the Supreme Court. The case, as well as others about medication abortion, raise questions about the role of the courts in reviewing the FDA’s findings about a particular drug. While most of the focus since the Dobbs ruling has been on the impact of that ruling on those who live in states that ban or greatly restrict abortion, the outcome of these medication abortion cases could also affect the availability of medication abortion to people in who live in states that protect abortion access. Furthermore, these cases could also have far-reaching implications for the FDA’s authority to continue to regulate not only mifepristone, but a wide range of other drugs that could be perceived to be controversial today and in the future.

Appendix

Appendix

| Appendix Table 1: Timeline of Regulatory Actions Regarding Mifepristone* | |

| Date | Action |

| March 1996 | The Population Council submitted a New Drug Application (NDA) for Mifeprex (Mifepristone). |

| September 2000 | FDA approved Mifeprex for the medical termination of pregnancy through 49 days’ gestation. The approval was granted under FDA’s regulations at 21 C.F.R. Part 314 Subpart H (Subpart H), which permitted FDA to impose conditions the agency deemed necessary to ensure the product’s safe use, including in this instance requirements regarding the capabilities and commitments of each healthcare provider who would be authorized to prescribe the drug and restrictions on how the drug would be distributed. |

| August 2002 | American Association of Pro-Life Obstetricians and Gynecologists (AAPLOG) and Christian Medical& Dental Associations and Concerned Women for America submitted a citizen petition requesting FDA revoke approval of Mifeprex. |

| September 2007 | Congress amended the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to give FDA authority to require an applicant to submit a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) if the agency determined that a REMS “is necessary to ensure that the benefits of the drug outweigh the risks of the drug.” 21 U.S.C. § 355-1(a)(1). |

| August 2008 | The GAO issued a report on the approval and oversight of Mifeprex following a request from several members of Congress. |

| June 2011 | FDA approved the Mifeprex REMS after Danco submitted an application on September 17,2008. The approved REMS maintained and augmented the Subpart H requirements imposed with the initial approval of Mifeprex. |

| March 2016 | FDA denied the 2002 citizen petition requesting to revoke approval of Mifeprex. |

| March 2016 | FDA updated and approved a new evidence-based regimen and drug label, which guides current clinical practice. This regimen approves use of medical abortions for up to 70 days (10 weeks) of pregnancy. |

| March 2018 | The GAO issued a report on FDA’s actions in approving the 2016 changes following a request from several members of Congress. |

| March 2019 | Plaintiffs AAPLOG and ACOP submitted a citizen petition to FDA asking the agency to “restore and strengthen elements of the Mifeprex regimen and prescriber requirements approved in 2000,” and “retain the Mifeprex [REMS], and continue limiting the dispensing of Mifeprex to patients in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals, by or under the supervision of a certified prescriber.” |

| April 2019 | FDA approved of GenBioPro’s abbreviated new drug application for a generic version of mifepristone. FDA determined that the generic drug was material the “same” as Mifeprex. With this approval, the FDA also approved a Mifepristone REMS program, covering both Mifeprex and the generic medication. |

| April 2020 | The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) sent a letter urging FDA to suspend enforcement of the in-person dispensing requirements of the Mifeprex REMS. |

| April 2021 | FDA responded to the letter from ACOG and SMFM, stating that during the COVID-19 public health emergency, the agency would exercise enforcement discretion with regard to “dispensing of Mifeprex . . . through the mail either by or under the supervision of a certified prescriber, or through a mail-order pharmacy when such dispensing is done under the supervision of a certified prescriber.” |

| May 2021 | FDA updated the Mifepristone REMS, adding gender-neutral language to the patient agreement form. |

| December 2021 | FDA responded to the 2019 citizen petition from plaintiffs AAPLOG and ACOP, addressing in detail their concerns, assertions, and the sources cited in support, but denying their request to restore the requirements approved in 2000 and to limit dispensing (for both Mifepristone and Misoprostol) in person. |

| January 2023 | FDA modified the Mifepristone REMS, removing the in-person dispensing requirement. |

| NOTES: *For the purpose of terminating pregnancy. The FDA has additionally approved a Mifepristone medication to treat Cushing’s disease. | |

PEPFAR Reauthorization 2023: Key Issues

This year, Congress will consider reauthorization of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), which was created in 2003 as the U.S. government’s signature global health effort in the fight against HIV. This would be PEPFAR’s fourth reauthorization. The program is broadly regarded as one of the most successful programs in global health history, with the U.S. government reporting tens of millions of lives saved over the past 20 years. Our analyses have also found positive spillover effects associated with the program beyond HIV, such as large, significant reductions in both maternal and child mortality and significant increases in some childhood immunization rates. At the same time, with a divided Congress, there are likely to be heightened disagreements over funding levels across the federal budget, potentially tied to the need to raise the debt ceiling later this year.

Following are fast facts about the program and top issues related to PEPFAR’s authorization and funding.

Fast Facts About PEPFAR

- Created in 2003 during the George W. Bush administration

- FY 2023 funding: $6.9 billion, with approximately $4.9 billion for bilateral HIV efforts and $2 billion for U.S. contributions to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria

- Spans more than 50 countries

- Reports saving 25 million lives

- Operates largely under permanent authorities of U.S. law that allow for ongoing funding and the continuation of the major structures of the program

- Would continue absent a reauthorization, provided funds are appropriated (although some time-bound requirements would end if a reauthorization bill is not passed or if Congress does not address them through another legislative vehicle)

What are authorization and reauthorization bills, and what is their connection with appropriations bills?

Established by House and Senate rules, the two-step process of authorization/appropriations supports the linkages between the authorizing and appropriating committees of each chamber:

- Authorization legislation establishes programs, policies, and organizational, oversight, and reporting requirements. It is also “intended to provide guidance to appropriators as to a general amount and under what conditions funding might be provided to an agency or program” before appropriations may be made. It may have time-limited provisions, including for funding.

- Reauthorization legislation allows existing law for programs and policies to be adapted to current circumstances, such as adding or updating reporting requirements, increasing oversight, and extending or modifying time-limited provisions.

- Appropriations legislation provides budget authority, allowing funding for an agency or program.