Mental health and substance abuse disorder services are needed by people of all ages, including older adults. In February 2023, 20% of adults 65 and older reported symptoms of anxiety and/or depression. Medicare covers a range of mental health and substance use disorder services, and Medicare Advantage plans are required to cover the same set of services as traditional Medicare. With increasing Medicare enrollment, the need for mental health and substance use disorder care will likely continue to grow. Members of Congress and the Biden Administration have introduced proposals to address concerns about barriers to mental health and substance use disorder care in Medicare. However, despite the rise in enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans, which now cover about half of people on Medicare and typically offer extra benefits beyond traditional Medicare, not much is known about the scope of mental health and substance use disorder benefits covered by these plans.

This brief describes the scope of mental health and substance use disorder benefits in Medicare Advantage plans, including extra benefits, cost sharing, and prior authorization and referral requirements, based on an analysis of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Medicare Advantage plan benefit and enrollment files for 2022. We limited the analysis to individual Medicare Advantage plans that are generally available to all beneficiaries for enrollment (which excludes plans sponsored by employers/unions and special needs plans (SNPs) that are offered to a defined group of beneficiaries).

Key Findings

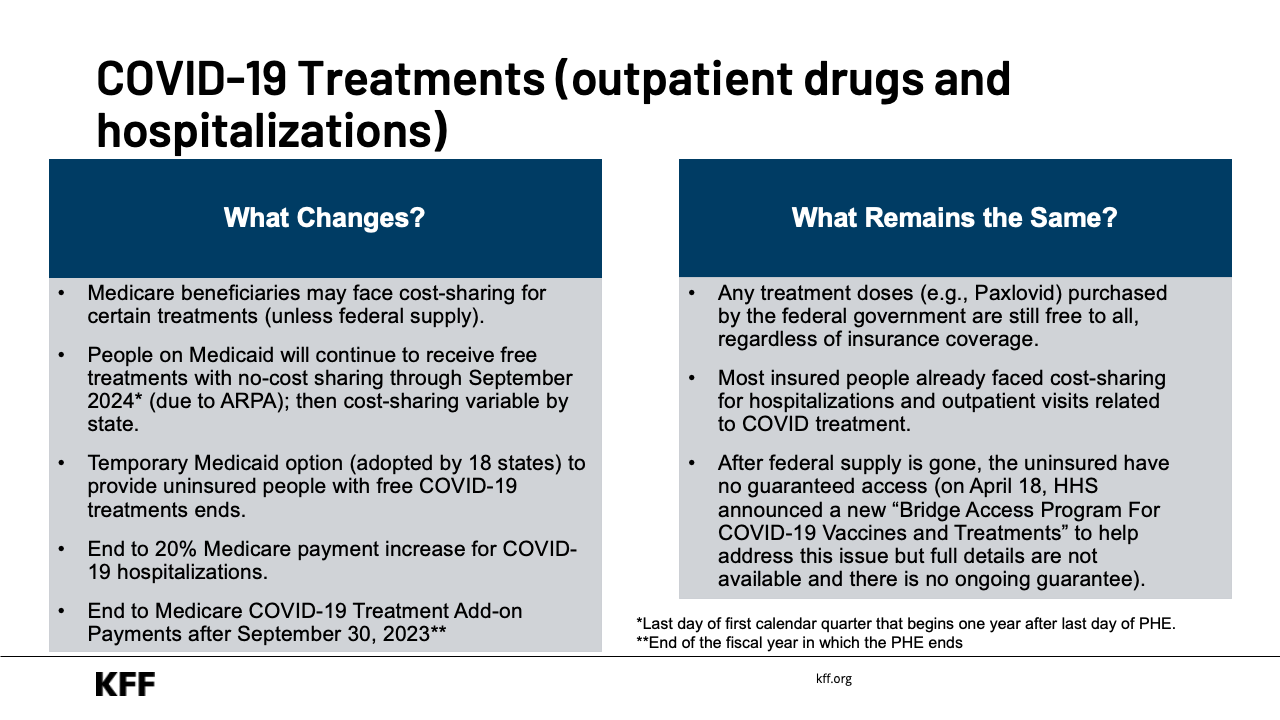

- A small share of plans provided extra benefits specifically for mental health and substance use disorders in 2022: 12% of enrollees were in plans that provided access to additional inpatient hospital psychiatric services, while 6% were in plans that offered tailored extra benefits, such as reduced cost sharing, to those with mood disorders or opioid use disorders.

- For in-network outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services, Medicare Advantage plans usually require cost sharing, which were typically copays rather than coinsurance, and varied across plans in 2022.

- About 60% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not cover out-of-network outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services in 2022; for the 40% who were enrolled in plans with some out-of-network coverage, the most common cost-sharing approach for out-of-network coverage of these services was coinsurance rather than a copay, typically 50%, though cost sharing also varied across plans.

- Prior authorization requirements are common: 98% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required prior authorization for some mental health and substance use disorder services in 2022.

- About one in four (26%) Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required referrals for some mental health and substance use disorder services in 2022.

- There are data gaps that limit the ability of beneficiaries and policymakers to understand the full extent of how mental health and substance use disorder benefits vary across Medicare Advantage plans and are working for enrollees. For example, there is not much information on whether Medicare Advantage enrollees are experiencing difficulty finding (and getting treated by) mental health providers in their plan’s network, the extent to which enrollees use in-network and out-of-network providers for these services, or their out-of-pocket liability for these services. Further, there is no data on prior authorization requests, denials, and appeals by type of mental health and substance use disorder service, by enrollee characteristics, or at the plan-level, such as for special needs plans versus plans available for general enrollment.

Coverage and Cost Sharing for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services

People on Medicare have the option of receiving their Part A and Part B Medicare benefits through traditional Medicare or a Medicare Advantage plan. For Medicare Advantage plans, the federal government contracts with private insurers to provide Medicare benefits to enrollees, and plans are required to meet federal standards. For example, Medicare Advantage plans are required to cover all Part A and B benefits covered under traditional Medicare, and Medicare Advantage plans are required to provide an out-of-pocket limit.

Medicare covers a range of mental health and substance abuse disorder services, both inpatient and outpatient services, and Part D plans cover outpatient prescription drugs used to treat these conditions. Medicare Part A covers inpatient care for beneficiaries who need treatment for a mental health condition in either a general hospital or a psychiatric hospital, though Medicare beneficiaries are only covered for up to 190 days in a lifetime for stays in a psychiatric hospital. Medicare Part B covers several outpatient services, including one depression screening per year, a one-time “welcome to Medicare” visit, which includes a review of risk factors for depression, and an annual “wellness” visit, where beneficiaries can discuss their mental health. Part B covers individual and group psychotherapy with doctors or with certain other licensed professionals, psychiatric evaluation, medication management, partial hospitalization, and opioid use disorder treatment services, among others.

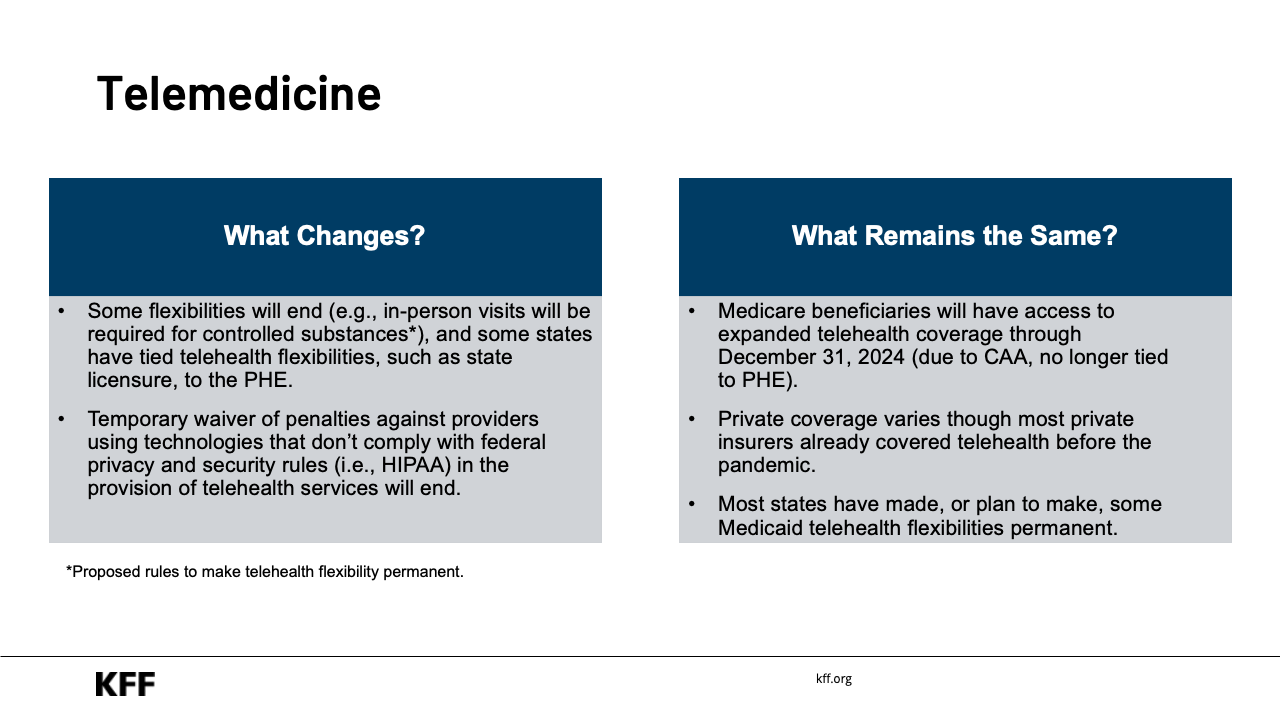

Medicare also covers some telehealth services under Part B, including for mental health and substance use disorder services as well as non-mental health related services, on both a permanent basis and on a temporary basis as part of the COVID-19 public health emergency. Medicare Advantage plans have additional flexibilities to provide telehealth benefits, and since 2020, Medicare Advantage plans have been permitted to include costs associated with telehealth benefits (beyond what traditional Medicare covers) in their bids for basic benefits. This benefit includes telehealth visits provided to enrollees in their own homes and services provided outside of rural areas (benefits not covered by traditional Medicare prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) and can be provided for mental health and substance use disorder services. In 2022, 98% of Medicare Advantage enrollees in individual plans had a telehealth benefit.

Medicare Advantage plans have flexibility when designing plan benefits and use rebate dollars to provide non-Medicare covered benefits, such as dental, vision, and hearing, as well as reduce cost sharing, and expand Medicare-covered benefits, such as by offering additional days of coverage in a psychiatric hospital. While Medicare Advantage plans may provide modified or reduced cost sharing compared to traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage cost sharing for Part A and B services cannot exceed cost sharing for those services in traditional Medicare on an actuarially equivalent basis. According to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), in 2023, about 39 percent of rebate dollars or $912 annually were used to lower cost sharing for Medicare services, although the allocation of lower cost sharing by benefit type, including for mental health, is not shown.

Most people with traditional Medicare have some kind of supplemental coverage (e.g. Medicaid, employer-sponsored coverage or Medigap) which helps with Medicare cost sharing. Out-of-pocket costs may differ between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans, and vary from one Medicare Advantage plan to another, though are subject to limitations.

Medicare Advantage plans can and do apply cost management tools to mental health and other services, such as prior authorization requirements, referrals, and limited networks that can restrict beneficiary choice of in-network physicians and facilities.

Plan Benefit Design

A small share of plans provided extra benefits specifically for mental health and substance use disorders in 2022: 12% of enrollees were in plans that provided access to additional inpatient hospital psychiatric services, while 6% were in plans that offered tailored extra benefits, such as reduced cost sharing, to those with mood disorders or opioid use disorders.

In 2022, 12% of enrollees were in plans that provided access to additional inpatient hospital psychiatric services as an extra benefit, including either additional days of coverage per benefit period and/or coverage of non-Medicare-covered stays. As noted above, Medicare beneficiaries are generally only covered for up to 190 days in a lifetime for stays in a psychiatric hospital. However, there is no publicly available data on how frequently extra benefits are used by enrollees.

While not necessarily specific to mental health and substance use disorders, there are other supplemental benefits that can be used toward services to address these conditions. For example, in 2022, 39% of enrollees were in plans that provided transportation benefits, which could be used to get to and from medical appointments for mental health and substance use disorder services. Because many supplemental benefits are applicable to all types of services, not just for mental health and substance use disorders, we do not go into detail on those benefits here.

As of 2019, Medicare Advantage plans may tie the availability of supplemental benefits to certain subgroups of beneficiaries, such as those with mental health disorders or diabetes, making different benefits available to different enrollees, as long as similarly situated enrollees are treated the same. This option, known as uniformity flexibility, allows Medicare Advantage plans to tailor supplemental benefits to enrollees with mental health or substance use disorders as well as reduce or eliminate cost sharing for certain services, and offer lower deductibles if they meet certain criteria.

In 2022, more than 1.1 million enrollees, or about 6% were in a Medicare Advantage plan that offered either reduced cost sharing or supplemental benefits to those with mood disorders (depending on the plan criteria) or opioid use disorders.

Chronic condition special needs plans (C-SNPs)

There are also other types of Medicare Advantage plans, called Special Needs Plans (SNPs), that are able to target plan benefits to enrollees with certain conditions. C-SNPs, which are for people with severe chronic or disabling conditions, can restrict enrollment to specific types of beneficiaries with significant or relatively specialized care needs, including beneficiaries with mental health conditions. In 2022, four firms offered C-SNPs for people with mental health conditions, covering about 1,800 enrollees. These plans are expected to provide benefits that meet the needs of enrollees, which can include but are not limited to, parity between medical and mental health benefits and services, no or lower cost sharing for mental health and substance use disorder services, and longer benefit coverage periods for inpatient services or other types of services.

Cost Sharing for Outpatient Services

For in-network outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services, Medicare Advantage plans usually require cost sharing, which were typically copays rather than coinsurance, and varied across plans in 2022. About 60% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not cover out-of-network outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services in 2022; for the 40% who were enrolled in plans with some out-of-network coverage, the most common cost-sharing approach for out-of-network coverage of these services was coinsurance rather than a copay, typically 50%, though cost sharing also varied across plans.

Under traditional Medicare, there is a $233 deductible (in 2022) and 20 percent coinsurance that applies to most services covered under Medicare Part B after the deductible is met. However, some mental health and substance use disorder services have different cost-sharing amounts, such as opioid treatment program services which do not require cost sharing, though the Part B deductible still applies for supplies and medications a beneficiary gets through an opioid treatment program provider.

Medicare Advantage plans can charge either copays or coinsurance for these services or no cost sharing at all. In 2022, when plans imposed cost sharing, nearly all required copays for in-network services and more frequently coinsurance for out-of-network services. Medicare Advantage plans’ cost sharing for outpatient mental health and substance use disorder benefits varied across plans, whether the service was in-network and out-of-network, and by service category (Table 1).

About six in ten (60%) Medicare Advantage enrollees did not have any coverage of mental health and substance use disorder services received from out-of-network providers in 2022, meaning enrollees in these plans would have to pay completely out-of-pocket to receive these services.

Therapy Sessions with a Psychiatrist or With Another Type of a Mental Health Provider

In-Network: These services consist of either individual or group therapy sessions with a psychiatrist or with other mental health providers, such as clinical psychologists and clinical social workers and other professional authorized by states to furnish mental health services. About 9 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees (90%) were in plans that charge cost sharing for therapy sessions, with virtually all charging copays (88%) rather than coinsurance (2%). The most common copay amount across plans was $40, though copays ranged from $2 to $40. For the small share of enrollees in plans with coinsurance, the most common coinsurance amount was 20% and ranged from 15% to 20%. In total, about 10% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not require cost sharing for therapy sessions. (For more detailed data on each therapy session type, see Table 1).

Out-of-Network: About 4 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees (41%) were in plans that provided coverage for out-of-network individual or group therapy sessions. More enrollees were in plans that charged coinsurance (22%) rather than copays (18%), with the most common coinsurance being 50%, and the most common copay being $40. About 6 in 10 (59%) Medicare Advantage enrollees were plans that did not provide coverage for out-of-network therapy sessions. Individual and group sessions are displayed together for out-of-network services due to how data are input in the Medicare Advantage benefit files.

Partial Hospitalization

In Network: These services include a more structured program of individualized and multidisciplinary outpatient psychiatric treatments that is more intensive than in a doctor or therapists’ office, as an alternative to an inpatient stay. Nearly 9 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees (86%) were in plans that charged cost sharing for each day of partial hospitalization, with virtually all charging daily copays (84%) rather than coinsurance (2%). The most common copay amount was $55, though copays ranged from $5 to $55 across plans. The most common coinsurance amount was 20% and ranged from 14% to 20%. In total, about 14% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not require daily cost sharing for partial hospitalization.

Out-of-Network: About 4 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees (41%) were in plans that provided out-of-network coverage for partial hospitalization. More enrollees were in plans that charged coinsurance (27%) rather than copays (13%). Coinsurance of 50% per day was the most common across plans, while the most common copay amount was $75 per day. About 6 in 10 (59%) Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not provide coverage for out-of-network partial hospitalization services.

Opioid Treatment Program Services

In Network: Medicare Advantage enrollees with opioid use disorder can receive services through an opioid treatment program, which may consist of medication-assisted treatment (MAT), substance use counseling, individual and group therapy, toxicology testing, intake activities, and periodic assessments. About 6 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees (63%) were in plans that charged cost sharing for various opioid treatment program services, with mostly all charging copays (57%) rather than coinsurance (4%). The most common copay amount was $40, though copays ranged from $5 to $250 across plans. The most common coinsurance amount was 20%, and ranged from 10% to 50%. About 2% of enrollees may have either had a copay or coinsurance. In total, 37% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not require cost sharing for opioid treatment program services.

Out-of-Network: About 4 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees (40%) were in plans that provided coverage for opioid treatment program services. More enrollees were in plans that charged coinsurance (22%) rather than copays (6%). The most common coinsurance amount was 50%, while the most common copay amount was $65 across plans. About 6 in 10 (60%) Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that did not provide coverage for out-of-network opioid treatment program services.

For information on individual and group therapy sessions for substance use disorder as well as more detailed information on other services, see Table 1.

Prior Authorization and Referrals

In 2022, 98% of Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required prior authorization for some mental health and substance use disorder services. About one in four (26%) Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required referrals for some of these services.

Prior Authorization

Medicare Advantage plans can impose prior authorization requirements, which entail enrollees getting approval from their plan prior to receiving a service, and if approval is not granted, then the plan generally does not cover the cost of the service. According to a KFF analysis, over 35 million prior authorization requests were submitted to Medicare Advantage plans in 2021.

In 2022, virtually all Medicare Advantage enrollees (98%) were in plans that required prior authorization for some mental health and substance use disorder services. More than 9 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees were plans that required prior authorization for inpatient stays in a psychiatric hospital (93%) and partial hospitalization (91%). Slightly more than 8 in 10 Medicare Advantage enrollees were in plans that required prior authorization for opioid treatment program services (85%), therapy sessions with other mental health providers besides psychiatrists (sometimes referred to as mental health specialty services; 84%), therapy sessions with a psychiatrist (84%), and outpatient substance abuse disorder services (83%) (Figure 1).

Health insurers use prior authorization to both contain spending and prevent enrollees from receiving unnecessary or low-value services, though there are some concerns these requirements may create barriers and delays to receiving necessary care. However, data are not available to analyze prior authorization and appeal rates by type of service, including mental health and substance use disorder services, so it is unclear to what extent prior authorization creates barriers to obtaining care.

To address some concerns related to the use of prior authorization in Medicare Advantage, CMS finalized a rule in April 2023 that would clarify the coverage criteria Medicare Advantage plans can use when making prior authorization determinations, including that they follow traditional Medicare coverage guidelines when making medical necessity determinations, which would apply to both mental health and non-mental health related services. Further, CMS clarified that mental health services needed in emergency medical situations cannot be subject to prior authorization.

A proposed rule issued by CMS in December 2022 would institute an electronic prior authorization process in Medicare Advantage and increase the speed at which Medicare Advantage plans must respond to prior authorization requests, which would also apply both to mental health and non-mental health related services. This proposal is similar to legislation that passed the House during the 117th Congress.

referRals

Medicare Advantage plans can also impose referral requirements, in which a primary doctor must provide a written letter in order for a patient to see a specialist for services, and if not provided, then the plan generally does not cover the cost. In contrast, traditional Medicare generally does not require prior referrals for services.

About one in four Medicare Advantage (26%) enrollees were in plans that required referrals for some mental health and substance use disorder services in 2022, including inpatient hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital (22%), partial hospitalization (21%), opioid treatment program services (20%), therapy with a psychiatrist (19%), outpatient substance abuse disorder services (19%), and therapy sessions with other mental health providers besides psychiatrists (18%) (Figure 1).

While some data on the use of referrals in Medicare Advantage is available, little is known if and how they impact enrollees’ access to care or create barriers to care.

Data Gaps and Limitations

There are data gaps that limit the ability of researchers and policymakers to understand the full extent of how mental health and substance use disorder benefits in Medicare Advantage plans are working for enrollees.

Access to Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Providers: There is not much information on whether Medicare Advantage enrollees are experiencing barriers accessing mental health providers in their plan’s network and the extent to which enrollees use in-network and out-of-network providers for these services. Prior KFF research has shown that access to psychiatrists was more restricted than for other physician specialties in Medicare Advantage plans, but the analysis did not examine network inclusion of other types of mental health providers, such as clinical psychologists and clinical social workers. Psychiatrists are also less likely than other specialists to take new Medicare (or private insurance) patients, and they’re more likely than other specialists to “opt out” of Medicare altogether, meaning they do not participate in the Medicare program; this may impact availability of these providers in Medicare Advantage networks and also affects access to those providers for people in traditional Medicare.

Research from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has also shown that consumers with various types of insurance (not specific to Medicare Advantage plans) face challenges accessing mental health care in-network, which may be due in part to providers not accepting new patients or long wait times to see providers. CMS recently finalized a rule that seeks to address some of these barriers, including applying Medicare Advantage network adequacy requirements to clinical psychologists and clinical social workers (in addition to psychiatrists), and notifying enrollees when their mental health providers are dropped mid-year from networks. However, little is still known about the extent Medicare Advantage enrollees specifically are experiencing barriers accessing providers in-network and how often enrollees seek out-of-network providers for these services.

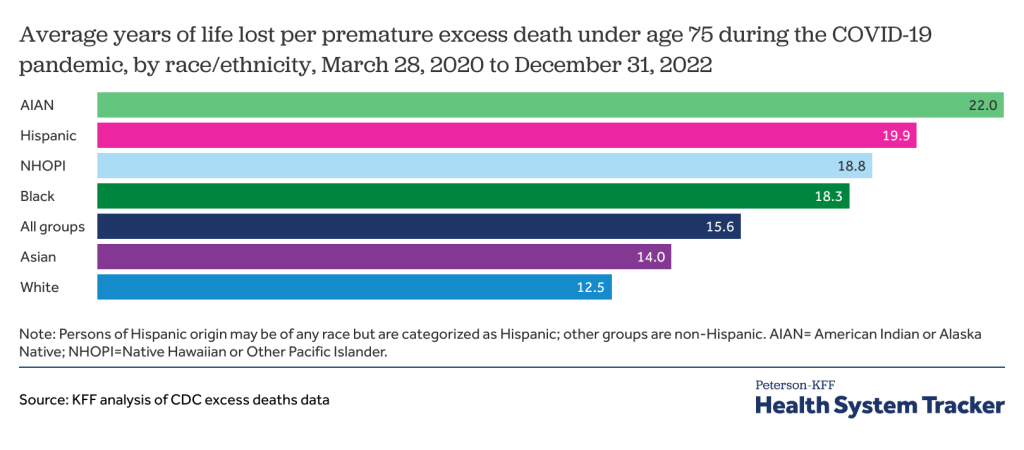

Out-of-Pocket Liability for Enrollees’ Use of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Services: CMS does not publish data on Medicare Advantage enrollees’ out-of-pocket liability for services, including mental health or substance use disorder services. Having information about enrollee liability would facilitate comparisons of out-of-pocket spending both across plans and compared to traditional Medicare. It could additionally help compare whether there are differences in cost-burdens across subgroups of beneficiaries, including by race/ethnicity, sex, age, or diagnosed health conditions.

Prior Authorization Requests by Type of Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Service: Data is not reported to CMS on prior authorization requests, denials, and appeals by type of service, enrollee characteristics, or by plan type, including for mental health and substance use disorder services. Therefore, it is not possible to assess whether prior authorization requests for certain types of mental health and substance use disorder services are denied more often by some plans than others, or whether prior authorization requests tend to be denied more for some types of services than others. Additionally, plans are not required to report prior authorization data by demographic characteristics of Medicare Advantage enrollees, which make it impossible to assess whether prior authorization requirements have a disproportionate impact on certain subpopulations of enrollees, which could affect access to care, out-of-pocket costs, and health outcomes. Further, the aggregate-level data reported by Medicare Advantage insurers to CMS and made available in a public use file are only available at the contract, rather than plan level. Contracts can include multiple types of Medicare Advantage plans – for example, sometimes combining those available for individual purchase with SNPs. By aggregating data in this way, it is not possible to assess variations in prior authorization practices across plans within a contract, including across plans that serve different populations.

Discussion

Medicare Advantage plans cover all mental health and substance use disorder services covered under Medicare Parts A and B. Coverage of these services may differ between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage plans because Medicare Advantage plans have flexibility to offer additional benefits, impose different cost-sharing amounts (if actuarially equivalent), employ utilization management tools such as prior authorization and referrals, and rely on defined networks of providers, all of which may vary from one plan to the next. Differences between traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, and among Medicare Advantage plans, can pose challenges for beneficiaries to decipher.

While there is great interest in how well Medicare Advantage plans are serving enrollees’ mental health and substance use disorder needs, lack of data limits the extent to which policymakers, researchers and beneficiaries can fully answer that question. There is little data on the breadth of provider networks and what that means for access to services or how frequently enrollees seek care out-of-network. There is no data available on out-of-pocket liability for these services in Medicare Advantage plans, nor how out-of-pocket spending compares to non-mental health services both in Medicare Advantage and compared to traditional Medicare. There is also no data on how often plans impose prior authorization for various mental health and substance use disorder services and how often that results in delays or denials of care by type of service, by enrollee characteristic, or by plan type.

As part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, the GAO is directed to conduct a study comparing the mental health and substance use disorder benefits offered by Medicare Advantage plans to traditional Medicare and to other benefits offered by Medicare Advantage plans, which may provide more insight on some of these issues. The results of this study are expected in 2025.

Given the number of people aging onto Medicare, increasing enrollment in Medicare Advantage, and mental health needs among the Medicare population, ensuring access to affordable mental health and substance use disorder services will be an ongoing issue.

This work was supported in part by AARP Public Policy Institute (PPI). KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Methods

The CMS Medicare Advantage Plan Benefit Package (PBP) files and enrollment files for 2022 were used to examine mental health and substance use disorder coverage, cost sharing, prior authorizations, and referrals for people enrolled in individual Medicare Advantage plans open for general enrollment (e.g., excludes employer plans and special needs plans). Enrollment data are from the March 2022 Monthly Enrollment by Contract/Plan/State/County published by CMS. Enrollment data are only included in the analysis if the plan-county enrollment is at least 11 enrollees.

We additionally remove cost plans, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) plans, and medical saving account plans (MSAs). These plans were removed as they either have unique enrollment requirements, are paid differently, or are structured significantly different from traditional Medicare Advantage plans.

We also remove plans missing any key variables used in the analysis, consistent with our other work. For this analysis, private fee-for-service (PFFS) plans were dropped due to this requirement.

Plans input a minimum and maximum cost-sharing amount in the PBP. Sometimes these values are equal; but they could also differ for various reasons, including cost-sharing differences based on where services are received. We only use the maximum cost-sharing amount plans report (including for the ranges) as this better reflects what enrollees may face. Additionally, even if plans report that they require cost sharing, we consider the plan to have no cost sharing if the maximum amount is zero ($0 copay or 0% coinsurance).

The PBP is filled in by plans and submitted to CMS. As such, if plans submitted any inaccurate data, that would be included in the analysis.