An Overview of State Approaches to Adopting the Medicaid Expansion

Introduction

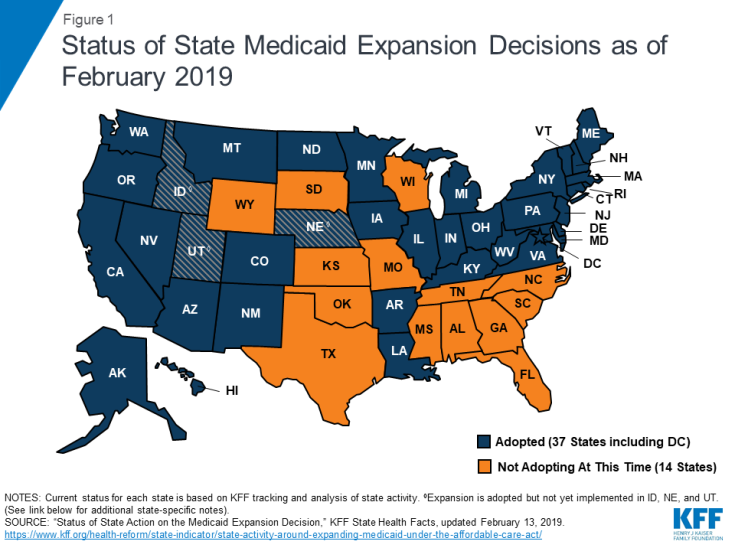

As enacted, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) broadened Medicaid’s role, making it the foundation of coverage for nearly all low-income Americans with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL) ($17,236 per year for an individual in 2019).1 However, the Supreme Court ruling on the ACA’s constitutionality effectively made the decision to implement the Medicaid expansion an option for states. For those that expanded, the federal government paid 100% of Medicaid costs of those newly eligible for coverage from 2014 to 2016. The federal share is gradually phasing down to 90% in 2020 (where it will remain in later years), still well above traditional federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) rates. As of February 2019, 37 states (including the District of Columbia) have adopted the Medicaid expansion2 (Figure 1). States’ initial approaches to adopting the Medicaid expansion have varied greatly by state based on state law, the political context, or other factors. While it does not cover how every state has enacted the Medicaid expansion, this issue brief highlights some of the different actions states have taken in response to the Medicaid expansion option. Each state’s circumstances are unique; the actions taken by one state may not apply to another state’s circumstances.

Overview of the Initial Processes Required to Adopt the Medicaid Expansion

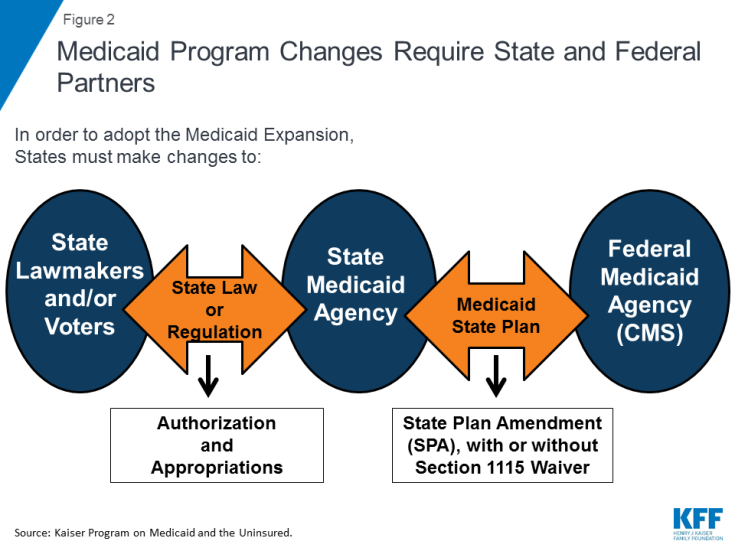

Medicaid is a jointly-operated program; state Medicaid agencies must work with federal partners to adopt the Medicaid expansion. The relationship between the state Medicaid agencies and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency administering the Medicaid program, is governed by a document called a Medicaid state plan. A Medicaid state plan describes how each state will operate its program, which is submitted to and approved by CMS. To make a change in its Medicaid program, the state Medicaid agency must submit and receive CMS approval of either a state plan amendment (SPA), which is used to make program changes that are allowed under current law, or a waiver request, which is a negotiated agreement involving changes to the operation of the state’s program that are not otherwise allowed under federal Medicaid law3 (Figure 2). However, all states are required to use a SPA to implement ACA expansion coverage, regardless of whether they also are seeking or have approval to make changes to the traditional expansion program under a Section 1115 waiver. Out of the 37 states that have adopted the expansion as of February 2019, eight states4 are currently using Section 1115 waiver authority to implement expansion programs in ways not otherwise permitted under federal law, and three states have adopted but not yet implemented the expansion (Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah). Kentucky is not yet included in the count of states implementing non-traditional Medicaid expansion programs under Section 1115 waiver authority, but the state has CMS approval to implement Section 1115 waiver changes affecting the expansion population later in 2019.5

However, before working with federal partners, state Medicaid agencies often must work with state lawmakers to obtain authorization and appropriations before implementing the Medicaid expansion (Figure 2). In order to make changes to Medicaid policy, such as expanding eligibility under the Medicaid expansion, most states must work with lawmakers (governors and/or legislatures) to make changes to either state laws and/or state regulations. While some states allow voters to authorize Medicaid program changes through ballot initiatives, lawmakers may still have significant influence over the final changes depending on variations in state law, including whether state law includes any restrictions on the legislature’s ability to amend or appeal the citizen initiatives after passage.6,7

Each state has different rules about which kinds of Medicaid policy changes, if any, can be authorized through changes in regulation (and therefore by agencies at the direction of the governor) or must be made through changes to state statute (and therefore require legislative approval or voter approval of a ballot initiative, if permitted in the state). For example, some states require state legislative action before state plan amendments or Section 1115 waiver requests can be submitted by the state Medicaid agency to CMS for federal approval, and others do not. States also vary on whether legislative action is required to authorize changes to Medicaid benefits, cost-sharing, and other types of Medicaid policy changes.8 This varies, at least in part, on how the Medicaid program was incorporated into state statute when the state originally enacted the program decades ago and the changes to rules and regulations enacted in the years since. In addition to authorization, state Medicaid agencies must also work with state lawmakers to obtain appropriations to fund the Medicaid policy change(s). Some states require legislative action to appropriate federal dollars as well as state dollars; others do not.

State Approaches to Medicaid Expansion Adoption

States’ initial approaches to Medicaid expansion adoption have varied greatly by state based on state law, the political context, or other factors. However, these approaches generally fall into four broad categories: adoption through the standard legislative process, adoption through the standard legislative process with a Section 1115 waiver to modify the traditional expansion program, adoption through executive action, and adoption through a ballot initiative. The following sections walk through each of these four categories, providing state examples and discussing the benefits and challenges associated with each approach. While states’ approaches may evolve over time and many states have made changes to their expansion programs post-implementation, the sections below focus primarily on the initial approaches states have taken to adopt the expansion.

Adoption Through the Standard Legislative Process

Many of the states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion have done so initially through the standard legislative process – legislation was passed authorizing the Medicaid expansion (either in a stand-alone bill or as part of budget legislation) – and expansion was implemented under SPA authority. For example, Minnesota9 and Maryland10 passed legislation during their 2013 regular legislative sessions to enact the Medicaid expansion. Other states, such as New York11 and New Mexico,12 included the Medicaid expansion as part of budget bills passed in 2013. In each of these states, the governor and legislature supported the Medicaid expansion. The standard legislative process has also worked in some states where adopting the Medicaid expansion was initially supported by one branch but not the other. For example, in Arizona, Governor Brewer strongly supported adopting the Medicaid expansion while the state legislature initially was hesitant; after lobbying legislators and building public support, legislators passed the state’s budget with the Medicaid expansion.13

Adoption Through the Standard Legislative Process with a Section 1115 Waiver to Modify the Traditional Expansion Program

While Section 1115 waivers require additional steps to obtain federal approval, the legislative process remains largely the same at the state level. The majority of states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion to date have done so within federal rules and options to receive the associated enhanced federal matching funds for newly eligible individuals. All states are required to use a SPA to implement ACA Medicaid expansion coverage, however, some states have obtained approval through Section 1115 waivers to implement the expansion in ways that extend beyond the flexibility provided by the law.14 While Section 1115 waivers require additional steps to obtain federal approval, the process may be largely the same at the state level, as if the state were not seeking expansion program changes through a waiver. For example, lawmakers in Iowa,15 Michigan,16 and Montana17 approved legislation adopting the Medicaid expansion through their standard legislative processes. While the legislation outlined their alternative Medicaid expansion requests and conditioned approval on federal waiver approval within a set timeframe, the legislatures delegated development and submission of the final waiver proposal to the state Medicaid agencies. While each Medicaid expansion waiver is unique, some states have included common elements such as a “premium assistance” model in which the state uses federal Medicaid funds to purchase Marketplace coverage for enrollees or other private coverage; enrollee premiums; elimination of the non-emergency medical transportation benefit, which is otherwise required under Medicaid; and use of “healthy behavior incentives” to reduce enrollee premiums and/or copayments.18 In some states, Section 1115 expansion waiver programs have changed over time, as discussed in the “additional considerations” section below.

Some states have implemented the expansion through a two-step process, first implementing a traditional expansion program under a SPA while separately seeking approval for expansion program changes through a waiver, to be implemented at a later date. In contrast to the approach of states like Arkansas and Indiana that simultaneously implemented expansion coverage under a SPA and non-traditional expansion program elements under a Section 1115 waiver, the two-step sequential approach allows states to quickly implement expanded coverage while taking additional time to develop, negotiate the terms of, and prepare for implementation of the desired Section 1115 waiver. For example, New Hampshire implemented the expansion through SPA authority in August 2014; however, authorizing legislation19 required the state to obtain Section 1115 waiver authority to operate the expansion in a way that differed from the standard approach permitted under federal law. CMS approved New Hampshire’s waiver request in March 2015, and the state then transitioned the expansion program to a Marketplace premium assistance model under the waiver authority in January 2016. Virginia took a similar two-step approach to expansion when they adopted it as part of the FY 2019-2020 budget that Governor Northam signed into law in June 2018.20 This legislation authorized the state Medicaid agency to implement expansion group coverage through a SPA and separately submit a waiver application seeking CMS approval for other new program elements that require waiver authority. New expansion coverage became effective in Virginia under a SPA in January 2019, and the state is currently negotiating the terms of a waiver request (with provisions applying to both expansion and traditional Medicaid populations) that they submitted in November 2018.21 This two-step approach enables the state to make coverage available more quickly while taking additional time needed to develop, negotiate, and implement more complex policies through a waiver.

Adoption Through Executive Action

While enactment of the expansion has involved the legislature in most expansion states, some governors have adopted the expansion through executive action without approval of the legislature. For example, in May 2013, former Democratic Governor Beshear of Kentucky and former Democratic Governor Tomblin of West Virginia adopted the expansion through executive orders. Expansion was also initially adopted without approval from the legislature in Pennsylvania. Former Republican Governor Corbett negotiated a Section 1115 waiver to implement the Medicaid expansion with CMS that was approved in August 2014, and implemented on January 1, 2015.22,23 Former Independent Governor Walker of Alaska took a similar approach after he was unable to persuade the Alaska Legislature to adopt the expansion in early 2015 (he took office in December 2014). Governor Walker announced his intent to expand through executive action on July 16, 2015, and expanded coverage became effective in Alaska on September 1, 2015.24 The most recent state to adopt the expansion through executive action was Louisiana. Democratic Governor Edwards issued an executive order25 to expand on his second day in office (January 12, 2016); expanded coverage became effective on July 1, 2016. Some expansions through executive action, including those in Kentucky26,27 and Alaska,28 have faced court challenges.

Former Republican Governor Kasich of Ohio adopted the expansion without support from the full Legislature by attaining approval to use federal expansion funds from a seven-member legislative panel. In October 2013, former Governor Kasich of Ohio secured support from the Legislature’s Controlling Board, a bipartisan legislative panel, to use available federal funds to expand Medicaid. This panel’s support allowed him to expand without approval from the full Legislature, which had consistently refused to authorize the expansion in previous months. Ohio law requires that money must be formally appropriated before it can be spent, and this is typically done through a vote of the General Assembly, but the Controlling Board also has the authority to adjust appropriations.29 This approach to expansion in Ohio faced a court challenge but was ultimately upheld.30

Some states have enacted laws prohibiting Medicaid expansion without legislative approval. While most states have adopted the Medicaid expansion after agreement has been reached between governors and state legislatures, some legislatures have sought to ensure that legislative approval is required before adoption of the Medicaid expansion can take effect. In March 2013, former Governor McCrory of North Carolina signed legislation that prevented any department, agency or institution of the state from expanding eligibility under the ACA Medicaid expansion in North Carolina unless directed to do so by the General Assembly.31 Similar stand-alone legislation was also passed in states such as Georgia,32 Tennessee,33 and Kansas.34 Legislatures in other states, such as Virginia, have included language requiring legislative approval before implementing the Medicaid expansion in state budgets.35

Most recently, Republican legislators in Wisconsin passed and outgoing Republican Governor Walker signed legislation during a lame-duck session in December 2018 restricting the executive branch’s authority to make changes to the Medicaid program (this occurred just before the start of new Democratic Governor Evers’ administration in January 2019). The new law effectively prohibits the Wisconsin governor from expanding Medicaid without some involvement from the Legislature.36,37 On January 8, 2019, Governor Evers signed an executive order directing the Department of Health Services to develop a plan to expand Medicaid;38 however, Republican leaders in the Legislature signaled that the Legislature would be unwilling to support it.39

Adoption Through a Ballot Initiative

Multiple states have adopted the Medicaid expansion through a ballot initiative. After former Governor LePage vetoed five Medicaid expansion bills passed by the state’s legislature, Maine voters made their state the first to adopt expansion through a ballot initiative (with 59% of voters’ support)40 in November 2017.41,42 Three additional states adopted expansion through ballot initiatives the following year in November 2018: Idaho43 (supported by 61% of voters),44 Nebraska45 (supported by 54% of voters),46 and Utah47 (supported by 53% of voters).48 Previous attempts by Medicaid expansion supporters to fully expand coverage to 138% FPL through the regular legislative process in all of these states were unsuccessful. Additional states are likely to attempt to adopt expansion through ballot initiatives in 2020. The Fairness Project, a key group that supported successful 2018 expansion ballot initiatives, is considering mounting similar ballot initiative campaigns in Florida, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, and/or Wyoming.49 These six states are the only non-expansion states as of February 2019 in which citizens can initiate a public vote on the expansion issue.50

Voter-approved ballot measures may face barriers to implementation based on state law requirements, efforts to block or amend the policies by legislators or governors, or legal challenges. Although the ballot initiative process may offer a path to expansion adoption in states where legislators or governors are unwilling to support it, experiences in Maine, Idaho, and Utah demonstrate that voter-approved measures may not be implemented quickly or as written without significant changes. Idaho and Utah are among 11 states (out of the 21 states that allow state laws to be adopted via a ballot initiative process) that have no restrictions on how soon or with what majority state legislators can repeal or amend initiated statutes.51

As a result, lawmakers in Utah passed legislation52 on February 11, 2019 that makes significant changes to the approach to expansion approved by voters. Utah voters approved a full expansion to 138% FPL, an April 1, 2019 implementation date, and a sales tax increase funding mechanism for the state’s share of expansion costs.53 However, the new legislation directs the Utah Department of Health to request Section 1115 waiver authority to make a number of changes including to use ACA enhanced federal matching funds for a partial expansion to 100% FPL, to add a work requirement as a condition of eligibility, to cap enrollment in expansion coverage, and to incorporate a per capita cap on federal reimbursement. Initially, the state may seek a waiver to implement a partial expansion to 100% FPL with capped enrollment at the regular state match rate.54 Enrollment caps for the expansion population and partial expansion with enhanced federal matching funds are policies that CMS has not approved in any other state to date.55

Lawmakers in Idaho are also considering a bill that would make changes to the expansion program approved by voters, including a “trigger provision” ending the expansion program if federal funding levels for the expansion population drop below a 90% match rate and a provision directing the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare to apply for a Section 1115 waiver to implement a marketplace premium assistance program for expansion enrollees with incomes above 100% FPL.56

Maine’s experience in the year following approval of the expansion ballot measure demonstrates the potential for an unsupportive governor to delay or restrict implementation. The expansion measure passed by voters included specific requirements for the dates by which the state must submit a SPA and implement the expansion. However, former Republican Governor LePage delayed and refused to implement the expansion throughout the rest of his time in office.57 Expansion coverage was ultimately implemented in January 2019, after new Democratic Governor Mills signed an executive order on her first day in office directing the Maine Department of Health and Human Services to begin expansion implementation and provide coverage to those eligible retroactive to July 2018.58

Approved ballot measures may also face legal challenges with the potential to delay or block implementation. In Idaho, a conservative think tank opposed to expansion (the Idaho Freedom Foundation) filed a lawsuit asking the Idaho Supreme Court to declare the expansion under Proposition 2 unconstitutional for delegating too much power to the federal government and the state Department of Health and Welfare.59 However, on February 5, 2019, the Idaho Supreme Court upheld the Medicaid expansion and dismissed the lawsuit.60

Some states have sought to use ballot initiatives to secure or reject new funding sources for the state share of Medicaid expansion costs. For example, in Montana, a measure on the November 2018 ballot would have extended the state’s existing Medicaid expansion program beyond the current June 30, 2019 sunset date and raised taxes on tobacco products to finance the state’s share of expansion costs.61 However, Montanans voted the measure down after tobacco industry spent over $17 million on television advertisements and other efforts to defeat the measure.62 As of February 2019, the Montana Legislature is debating different proposals to extend the program beyond the sunset date, with Republicans pushing to add work requirements or other changes to the program. Unlike Montana, which sought to approve a new expansion funding source using a ballot initiative, Republican lawmakers in Oregon attempted to use a veto referendum to repeal provisions of a law passed by the legislature and signed into law by the governor in 2017 that increased assessments on hospitals and insurers to help fund the state’s share of expansion costs.63 The effort to repeal the provisions was ultimately unsuccessful: in January 2018, 62% of Oregonians voted to uphold the expansion funding provisions of the law.64

Additional Considerations Pre- and Post-Expansion Adoption

State approaches to expansion are not static and may change over time in response to elections, new policy options, or other factors. While state approaches to adopting the Medicaid expansion can generally be grouped into the four categories discussed above, state approaches vary widely within each category, and state approaches are not static—a state may change its approach over time in response to elections, new policy options, or other factors. For example, during the Governor Corbett administration, Pennsylvania attained CMS approval for and implemented a Section 1115 Medicaid expansion program. However, Corbett was defeated in the November 2014 election by current Democratic Governor Wolf, who transitioned Pennsylvania’s Medicaid expansion from a waiver program to a traditional (SPA) expansion program shortly after taking office on January 20, 2015.65 Conversely, Kentucky initially adopted the expansion through executive action and a SPA under former Democratic Governor Beshear, but following the election of Republican Governor Bevin, Kentucky has attained CMS approval for a Section 1115 waiver expansion program with new restrictions on expansion coverage (the state intends to implement the waiver later in 2019, however, litigation over the waiver is ongoing).66 Louisiana’s Medicaid expansion experience presents another example of the impact of elections. Former Republican Governor Jindal refused to implement expansion through the end of his term in January 2015, but current Democratic Governor Edwards (who campaigned on expansion) switched the state’s course and adopted it through an executive order on his second day in office.67

Some states’ expansion programs have evolved over time at the direction of the state legislature or based on requirements included in the original legislation adopting the expansion. In Arkansas, the original legislation adopting the expansion mandated that the Arkansas Legislature reauthorize the expansion program annually.68 Arkansas’ “private option” approach to Medicaid expansion has undergone multiple modifications since initial implementation in 2014, as a result of decisions during the reauthorization process, requirements in the original expansion legislation, and a gubernatorial transition in 2015 when Republican Governor Hutchinson succeeded former Democratic Governor Beebe.69 In Michigan, the original state legislation authorizing expansion included requirements directing the state to submit waiver and waiver amendment requests at multiple points in time in the years following initial implementation. The legislation specified program elements that were to be included in the waiver and amendment requests, and called for termination of the expansion program if the state failed to obtain CMS approval for these requests.70 After first implementing the expansion under a waiver in 2014, Michigan received approval for a second waiver request in December 2015 and approval for an amendment to the waiver in December 2018.71

Many expansion states, including those that originally implemented traditional expansion programs without a Section 1115 waiver, have used or are seeking Section 1115 waivers to make program changes that affect the expansion population, including adding work requirements as a condition of eligibility for coverage. As of February 2019, nine expansion states have approved or pending Section 1115 waivers that add work requirements as a condition of eligibility for expansion adults. This includes five states that are operating their expansion programs using Section 1115 waivers (Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Michigan, and New Hampshire), three states that are currently operating traditional expansion programs without Section 1115 waivers (Kentucky, Ohio, and Virginia; however, Kentucky plans to transition to a Section 1115 waiver expansion program later in 2019), and one state that has adopted but not yet implemented the expansion (Utah). In addition, a number of expansion states have approved or pending waivers that add eligibility and enrollment restrictions or benefit, copay, and/or healthy behavior provisions affecting expansion populations.72

Although an increasing number of states are pursuing work requirement waivers following January 2018 CMS guidance signaling a new willingness to consider such proposals (which were never previously approved under Democratic or Republican administrations), other states have taken alternative approaches to supporting work in their Medicaid expansion programs without requiring work as a condition of eligibility. For example, expansion-authorizing legislation in Montana also authorized the state to administer a voluntary workforce development program (known as the HELP-Link program). Following expansion and HELP-Link implementation, labor force participation among low-income Montanans ages 18-64 increased by four to six percentage points relative to the change among the same population in other states or relative to the change among higher-income Montanans.73 Although Louisiana considered multiple work requirement-related bills in 2018, the state ultimately adopted legislation creating a voluntary workforce training and education pilot program for people receiving public benefits (including Medicaid) that went into effect in August 2018.74 Similar voluntary work support programs are also under consideration in Kansas and Idaho as of February 2019.75,76

Expansion adoption through a ballot initiative does not guarantee direct implementation as approved by voters, and this approach may be more prone to challenges prior to implementation than other expansion adoption approaches. Almost all states with ballot initiative processes allow lawmakers to make changes to approved ballot measures without voters’ approval of the changes. Experiences in states that adopted the expansion through a ballot initiative to date suggest that lawmakers in states that were reluctant to expand through the standard legislative process may be interested in making significant changes to the voter-approved expansion programs prior to implementation. Lawmakers recently approved changes that significantly limit the coverage expansion adopted by voters in Utah, and changes to a voter-approved expansion measure are under consideration in Idaho. Expansion approaches adopted through the ballot may also face challenges or delays to implementation from litigation (as occurred in Idaho) or from resistant governors (as occurred in Maine).

Financing for the state’s share of expansion costs has been a major factor in the decision about expansion adoption in many states, and some states have tied expansion adoption or continuation to specific funding mechanisms for the state’s share of expansion costs. Funding for the state share of Medicaid expansion costs has been a major concern among lawmakers and others who are (or have been) reluctant to adopt the Medicaid expansion in their state. As a result, many states have included specific funding mechanisms in the original legislation adopting the expansion. For example, Utah’s expansion ballot measure included a 0.15% increase from 4.70% to 4.85% of the state sales tax (except for groceries) to finance the expansion or Medicaid and CHIP more broadly.77

Montana and Oregon are examples of states that sought to use ballot initiatives to secure or reject new funding sources for the state share of Medicaid expansion costs, as described in the ballot initiatives section above. Arizona’s budget legislation that enacted the expansion called for the implementation of a new hospital provider fee to fund state costs of the Medicaid expansion. This funding mechanism was challenged in court for being a tax, which under Arizona’s constitution, requires two-thirds majority to approve as opposed to the simple majority that approved the legislation. However, the Arizona Supreme Court rejected the challenge in March 2017, ruling that the assessment is legal and that Medicaid expansion could continue.78

In Louisiana, legislators passed a bill that provided a funding mechanism for expansion (allowing hospitals to implement an assessment) several months prior to expansion adoption.79 In response to concern about possible changes to federal expansion funding levels from those currently provided and specified in the ACA, a number of states have included “trigger provisions” in their expansion legislation that would end the expansion program if federal funding levels change.80

Conclusion

State approaches to adopting the Medicaid expansion have varied greatly by state based on state law, the political context, or other factors. Many states initially adopted the Medicaid expansion through the standard legislative process after gaining the support of both the administrative and legislative branches of state government, including states that implemented traditional expansion programs and those that implemented expansion programs in ways not otherwise permitted under federal law using a Section 1115 waiver. Other states initially adopted expansion through executive authority or a ballot initiative; however, the legislature may still play a role in the expansion adoption process depending on the approach and state law. Each state’s circumstances are unique; the actions taken by one state may not apply to another state’s circumstances. In addition, states’ approaches to expansion are not static and may change over time in response to elections, new policy options, or other factors.

Work requirements are often a major consideration for states debating adopting the expansion or making changes to an existing expansion program, especially following the Trump administration’s willingness to consider Section 1115 “community engagement” proposals that were never approved under previous administrations. While many states have added or are seeking such requirements under Section 1115 waivers, other states are taking an alternative approach by including (or considering) voluntary work support programs for the expansion population without conditioning eligibility on meeting a work hours and reporting requirement. Financing for the state’s share of expansion costs has also been a major consideration for many states in the initial decision about Medicaid expansion adoption and, in some cases, debates over continuation of the expansion program. Looking ahead, it will be important to monitor debates on expansion in the 14 remaining non-expansion states, monitor any potential changes to expansion programs in states that have already adopted the expansion (including potential changes in states that adopted through ballot initiatives), and assess the advantages and disadvantages associated with different approaches with regard to coverage, cost, and administrative capacity.