This Week in Coronavirus: May 1 to May 7

Every Friday, we’re recapping the latest on coronavirus from our tracking, policy analysis, polling, and journalism. Total cases in the U.S. are still climbing, and surpassed 1.2 million this week. Approximately 76,000 have died in the U.S. from COVID-19. Meanwhile, since last Thursday, actions to ease social distancing requirements went into effect in 28 states and 14 states extended social distancing measures. One of the most notable updates to our data trackers was that 33 total states are now reporting 25,000 across 6,000 LTC facilities. Two weeks ago, only 6 states reported this data.

Here are more of the latest coronavirus stats from KFF’s tracking resources:

Global Cases and Deaths: This week, total cases worldwide passed 3.85 million – with approximately 591,000 new confirmed cases added between April 30 and May 7. There were approximately 36,000 new confirmed deaths worldwide between April 30 and May 7.

U.S. Cases and Deaths: There have been over 1.26 million total confirmed cases in the U.S. There were approximately 188,000 new confirmed cases and 13,000 confirmed deaths in the United States between April 30 and May 7.

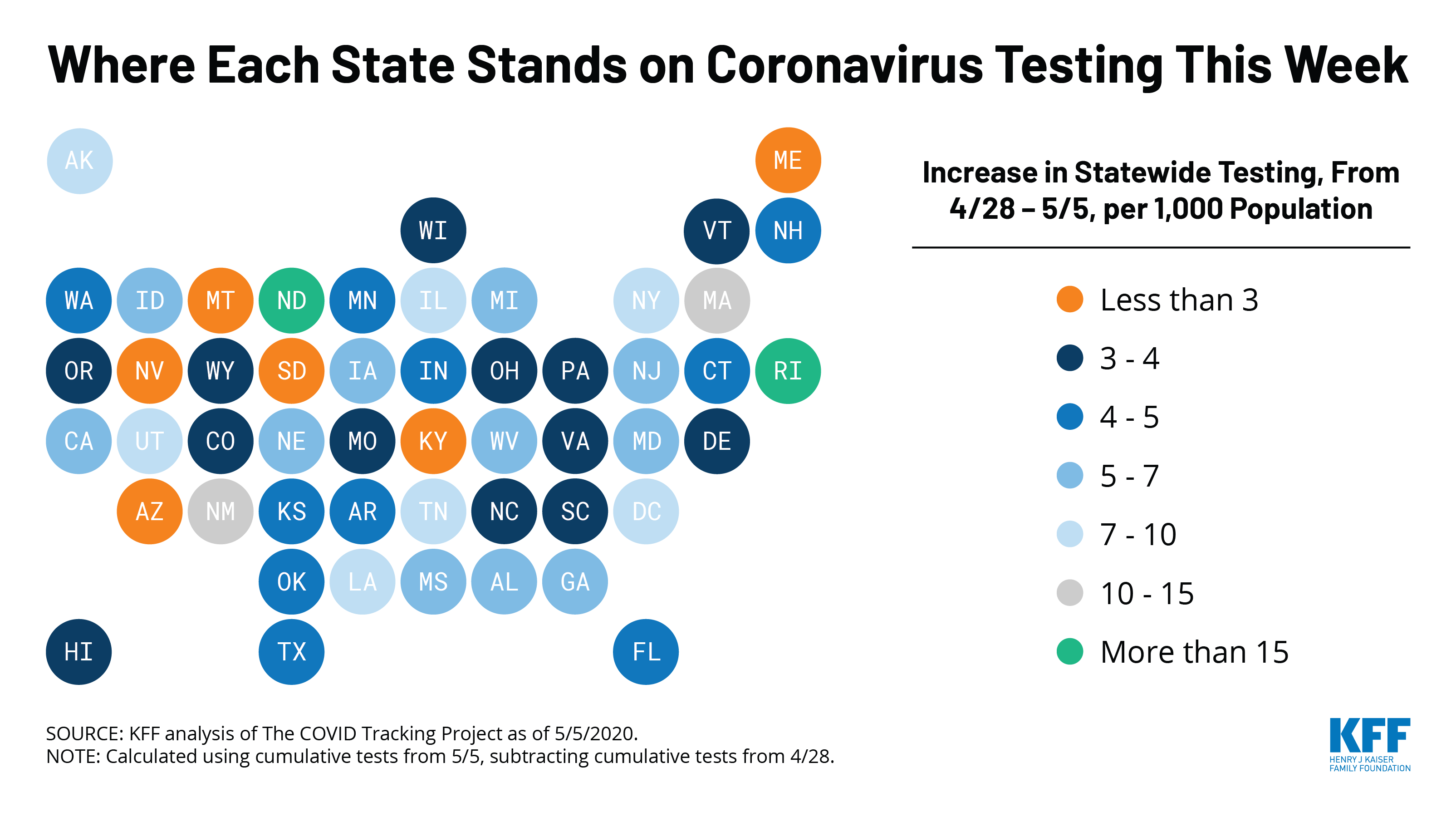

U.S. Tests: There have been approximately 8.1 million total COVID-19 tests with results in the United States — with over 2 million added since April 30. 15.4% of those tests were positive.

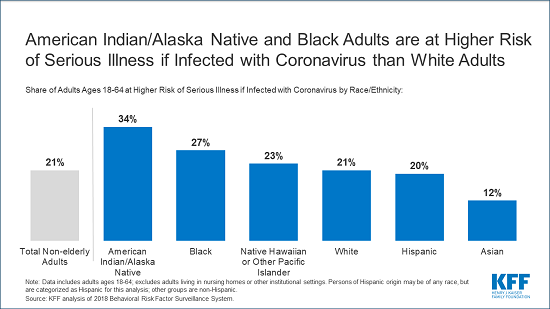

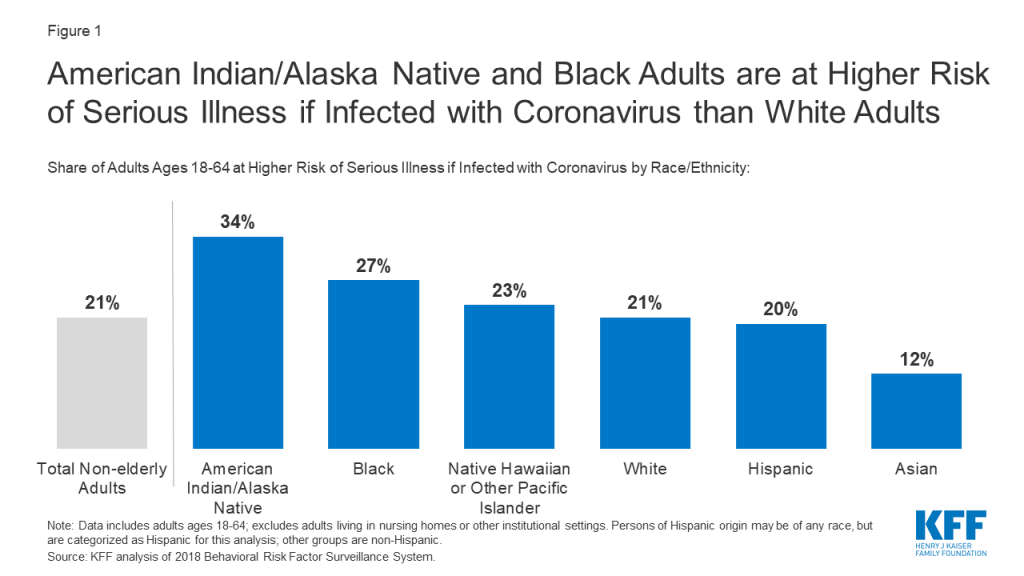

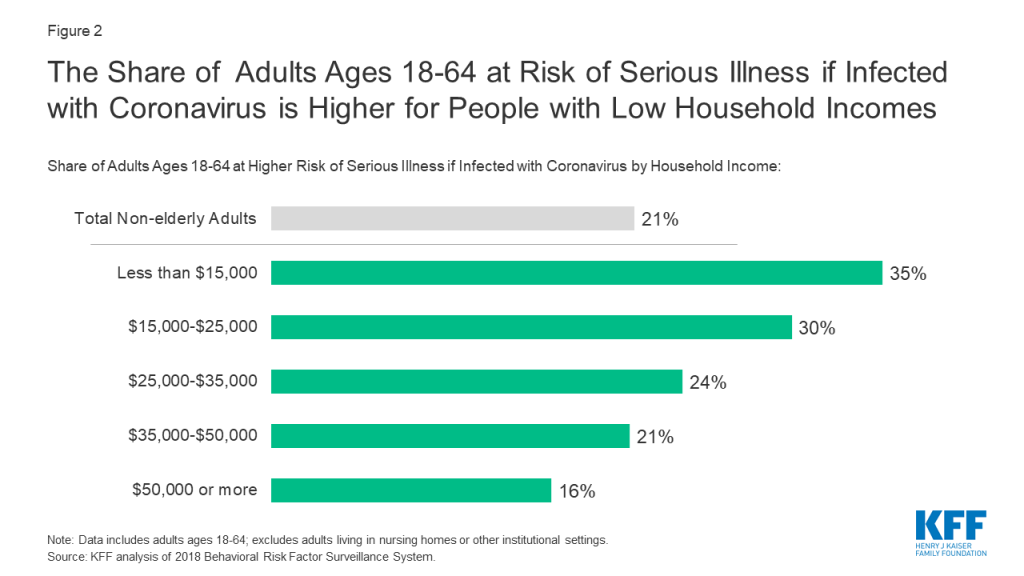

Adults at Higher Risk of Serious Illness if Infected with Coronavirus: 38% of all U.S. adults are at risk of serious illness if infected with coronavirus (92,560,223 total) due to their age (65 and over) or pre-existing medical condition. Of those at higher risk, 45% are at increased risk of serious illness if infected with coronavirus due to their existing medical condition such as such as heart disease, diabetes, lung disease, uncontrolled asthma or obesity. Among nonelderly adults, low-income, American Indian/Alaska Native & Black adults have a higher risk of serious illness if infected with coronavirus. For both race and household income, the higher risk of serious illness if infected with coronavirus is chiefly due to a higher prevalence of underlying health conditions and longstanding disparities in health care and other socioeconomic factors.

State Social Distancing Actions (includes Washington D.C.):

- Social Distancing: 28 states have eased social distancing measures: Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, and West Virginia. 14 states have extended social distancing measures: Arkansas, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, and Washington

- Stay At Home Order: original stay at home order in place in 29 states, stay at home order eased or lifted in 16 states, no action in 6 states

- Mandatory Quarantine for Travelers: original traveler quarantine mandate in place in 20 states, traveler quarantine mandate eased or lifted in 3 states, no action in 28 states

- Non-Essential Business Closures: original non-essential business closures still in place in 22 states, some or all non-essential business permitted to reopen (some with reduced capacity) in 23 states, no action in 6 states

- Large Gatherings Ban: original gathering ban/limit in place in 40 states, gathering/ban limit eased or lifted in 9 states, no action in 2 states

- State-Mandated School Closures: Closed in 7 states, closed for school year in 36 states, recommended closure in 1 state, recommended closure for school year in 6 states, rescinded in 1 state

- Restaurant Limits: Original restaurant closures still in place in 35 states, restaurants re-opened to dine-in service in 15 states, no action in 1 state

- Primary Election Postponement: Postponement in 14 states, cancelled in 1 state, no postponement in 36 states

- Emergency Declaration: There are emergency declarations in all states and D.C.

State COVID-19 Health Policy Actions (Includes Washington D.C.)

- Waive Cost Sharing for COVID-19 Treatment: 3 states require; state-insurer agreement in 3 states; no action in 45 states

- Free Cost Vaccine When Available: 9 states require; state-insurer agreement in 1 state; no action in 41 states

- States Requires Waiver of Prior Authorization Requirements: For COVID-19 testing only in 5 states; for COVID-19 testing and treatment in 6 states; no action in 40 states

- Early Prescription Refills: State requires in 18 states; no action in 33 states

- Premium Payment Grace Period: Grace period extended for all policies in 11 states; grace period extended for COVID-19 diagnosis/impacts only in 5 states; no action in 35 states

- Marketplace Special Enrollment Period: Marketplace special enrollment period in 12 states; no special enrollment period in 39 states

- Paid Sick Leave: 13 states enacted, 2 proposed, no action in 36 states

NEW: State Reports of Long-Term Care Facility Cases and Deaths Related to COVID-19 (Includes Washington D.C.)

- Data Reporting Status: 43 states are reporting COVID-19 data in long-term care facilities, 8 states are not reporting

- Cases in long-term care facilities: 127,693 (in 37 states)

- Deaths in long-term care facilities: 24,869 (in 33 states)

- Long-term care facilities as a share of total state cases: 15% (across 37 states)

- Long-term care facility deaths as a share of total state deaths: 38% (across 33 states)

Approved Medicaid State Actions to Address COVID-19 (Includes Washington D.C.)

- Approved Section 1115 Waivers to Address COVID-19: 1 state has an approved waiver

- Approved Section 1135 Waivers: 51 states have approved waivers

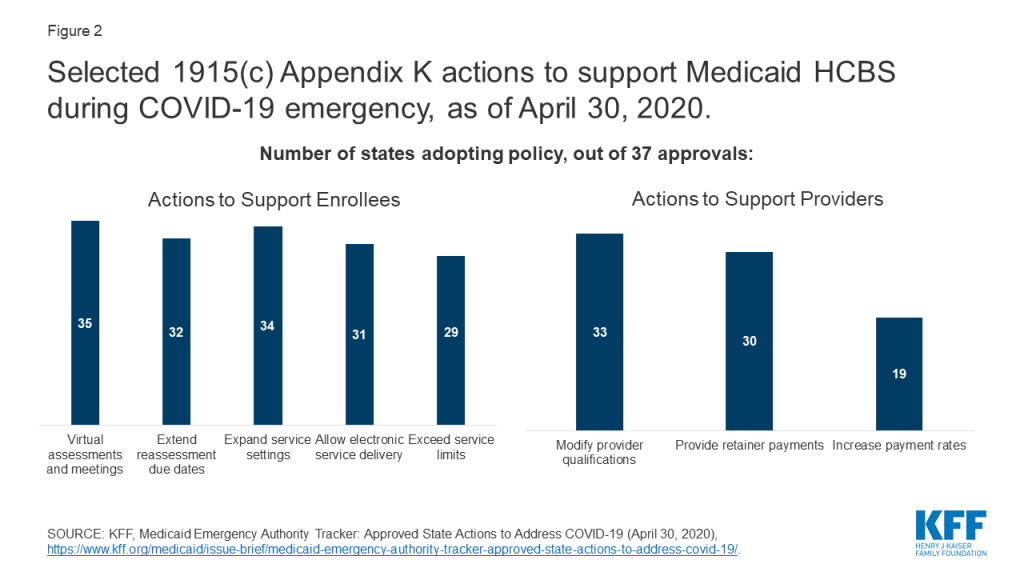

- Approved 1915 (c) Appendix K Waivers: 38 states have approved waivers

- Approved State Plan Amendments (SPAs): 29 states have temporary changes approved under Medicaid or CHIP disaster relief SPAs, 1 state has an approved traditional SPA

- Other State-Reported Medicaid Administrative Actions: 51 states report taking other administrative actions in their Medicaid programs to address COVID-19

This week’s posts in Coronavirus Policy Watch:

- At-Home SARS-CoV-2 Diagnostic Tests Could be a Breakthrough, But What Are the Limitations? (Blog)

- What We Can Learn from HIV in Communicating about COVID-19 (Blog)

- Lifting Social Distancing Measures in America: State Actions & Metrics (Blog)

- When Will The Unemployed Go Back To Work? Many Laid Off Workers Expect To Get Jobs Back In The Short-Term But Experts Caution About Long-Term Unemployment (Blog)

The latest KFF COVID-19 resources:

COVID-19 in the United States

- Low-Income and Communities of Color at Higher Risk of Serious Illness if Infected with Coronavirus (Issue Brief)

- COVID-19: Who Is Most At Risk of Serious Illness? (Video)

- COVID-19 Quiz (Quiz)

- Key Questions About the New Increase in Federal Medicaid Matching Funds for COVID-19 (Issue Brief)

- Key Questions About the New Medicaid Eligibility Pathway for Uninsured Coronavirus Testing (Issue Brief)

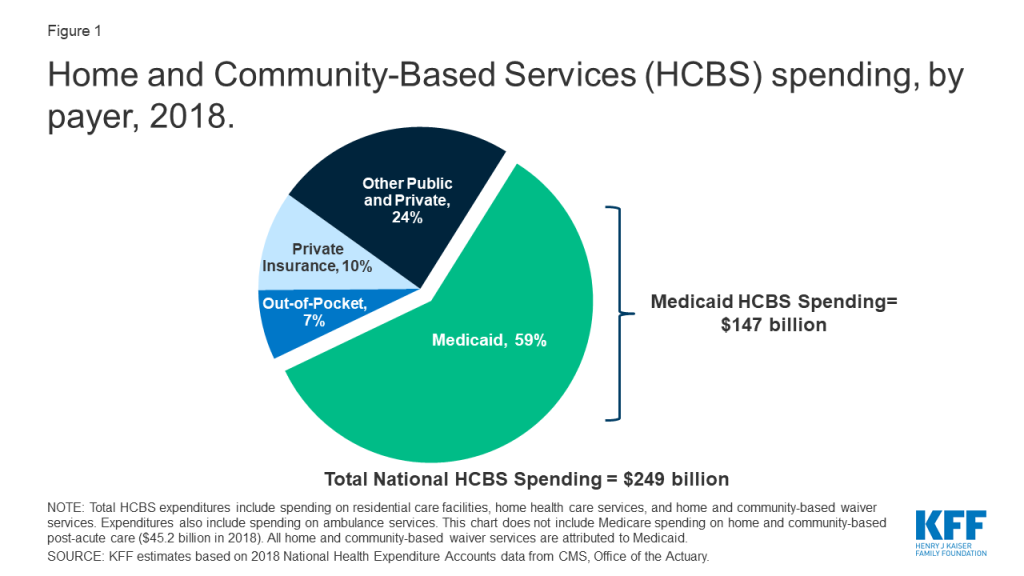

- How Are States Supporting Medicaid Home and Community-Based Services During the COVID-19 Crisis? (Issue Brief)

- How Publicly-Funded Family Planning Providers are Adapting in the COVID-19 Pandemic (Issue Brief)

- Updated: FAQs on Medicare Coverage and Costs Related to COVID-19 Testing and Treatment (Issue Brief)

- Pandemic Exacerbating Humanitarian Crises, Interrupting Aid Supply Chains, U.N. Agencies, Charities Say (KFF Daily Global Health Policy Report)

Trackers and Tools

- COVID-19 Coronavirus Tracker – Updated as of May 8, 2020 (Interactive)

- State Data and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus – Updated as of May 7, 2020 (Interactive)

- Medicaid Emergency Authority Tracker: Approved State Actions to Address COVID-19 – Updated as of May 7, 2020 (Issue Brief)

- COVID-19 and Related State Data (State Health Facts)

The latest KHN COVID-19 stories:

- Updated: Lost On The Frontline (KHN, The Guardian)

- Trying Out LA’s New Coronavirus Testing Regime (KHN, Washington Post)

- Looking For A Path To Reopen, Employers Weigh COVID Testing Of Workers (KHN, Time)

- Reopening In The COVID Era: How To Adapt To A New Normal (KHN)

- How The Pandemic And An Anti-Vax Health Official Are Roiling A Montana Community (KHN, Daily Beast)

- Economic Blow Of The Coronavirus Hits America’s Already Stressed Farmers (KHN)

- KHN’s ‘What The Health?’: Blowing The Whistle On Trump Team’s COVID Policies (Podcast)

- Eerie Emptiness Of ERs Worries Doctors As Heart Attack And Stroke Patients Delay Care (KHN, NPR)

- When Prisons Are ‘Petri Dishes,’ Inmates Can’t Guard Against COVID-19, They Say (KHN, NPR)

- Always The Bridesmaid, Public Health Rarely Spotlighted Until It’s Too Late (KHN, NPR)

- COVID-Plagued California Nursing Homes Often Had Problems In Past (KHN, KPCC)

- As COVID-19 Lurks, Families Are Locked Out Of Nursing Homes. Is It Safe Inside? (KHN, CNN)

- Palliative Care Helped Family Face ‘The Awful, Awful Truth’ (KHN, NPR)

- Testing In California Still A Frustrating Patchwork Of Haves And Have-Nots (KHN, NPR)

- As Lawmakers Reconvene, Not Everyone Agrees On COVID-Only Agenda (KHN)

- Viral Post Alleging Obama-Era Device Tax Caused Current PPE Shortage Is Way Off (KHN)

- Listen: A New Hope In The Battle Against COVID-19 (Podcast)