Introduction

The U.S territories — American Samoa, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and US Virgin Islands — and the Freely Associated States (FAS) — the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau — have faced an array of longstanding fiscal and health challenges, made worse by recent natural disasters and the coronavirus pandemic. Health centers are an important part of health care system in the U.S. territories and FAS, providing access to a range of primary care services to low-income and vulnerable individuals. They have also historically played a central role in the response efforts to previous natural disasters as well as the ongoing pandemic. Additional federal grant funding and Medicaid funding made available to the territories during the pandemic have helped health centers respond to the unique needs of their patients and weather the financial uncertainty related to the pandemic. Looking ahead, provisions in the Build Back Better Act would permanently increase federal Medicaid funding for the territories, enhancing Medicaid’s role in supporting the health care safety net in the territories.

This issue brief examines the role of community health centers in the U.S. territories and Freely Associated States during the COVID-19 pandemic. It presents findings from a survey of health centers and incorporates data from the Uniform Data System (UDS) as well as information from interviews with the Primary Care Associations in those regions (Pacific Islands Primary Care Association [PIPCA] and Asociación de Salud Primaria de Puerto Rico [ASPPR]).

The U.S. Territories and Freely Associated States

The U.S. has a unique relationship with the U.S. territories and Freely Associated States (FAS). The U.S. government provides different programmatic benefits to these Caribbean and Pacific islands compared to the U.S. states, and the territories and FAS receive different benefits compared to each other.

Individuals born in the five U.S. territories – American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI) – are U.S. citizens and nationals. Individuals in the territories receive some, but not all, federal safety net program benefits that are available to the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC). However, the programs that are available operate differently in the territories than they do in the states. For example, Medicaid in the territories features both a capped federal allotment (known as the Section 1108 allotment) and fixed federal matching rate (known as the federal medical assistance percentage, or FMAP) unlike federal Medicaid funding for states where federal dollars are uncapped and the FMAP is adjusted annually based on a state’s relative per capita income.

In contrast, individuals born in the three Freely Associated States (FAS) – the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau – are not considered U.S. citizens or nationals. Instead, the FAS are independent nations that each have a Compact of Free Association (COFA) with the U.S. government. Through this bilateral agreement, the FAS receive economic and military assistance from the U.S. government in exchange for allowing the U.S. to operate military bases on their soil. Because of this relationship, the FAS do not receive Medicaid funding and citizens of the FAS are not eligible for Medicaid unless they are residing in the states. Recently, the U.S. states were required to provide Medicaid benefits for FAS citizens without the previously mandatory five-year waiting period and U.S. territories were given the option to provide Medicaid benefits for FAS citizens.

Role of Health Centers in the U.S. Territories and FAS

Community health centers are located in all of the U.S territories and Freely Associated States. In 2020, there were 33 health center organizations (27 in the territories and six in the FAS) that operated 170 clinic sites in the U.S. territories and FAS (Table 1). Reflecting the significantly larger population of Puerto Rico compared to the other territories and FAS, the majority of health centers (22) are located in Puerto Rico. In contrast, there are four health center organizations operating in the Federated States of Micronesia, two health center organizations operating in USVI, and one health center in each of the smaller Pacific Island territories and the remaining FAS. Despite the challenges posed by the pandemic, the number of sites operated by health centers in the territories and FAS increased 8% from 2019 to 2020.

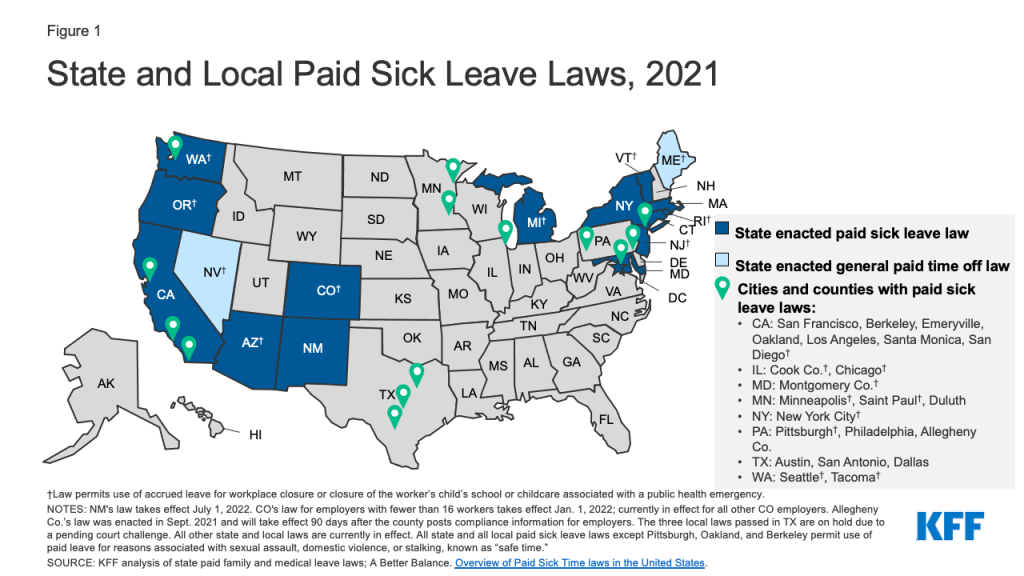

According to health centers in the territories and FAS that responded to the survey, the most prevalent health conditions among patients are heart disease and diabetes while the economic effects of COVID-19 and endemic poverty were cited as the most significant social issues. Responding health centers also reported obesity (42%) and mental health (33%) among the top three health issues. A smaller share (17%) said cancer was a prevalent condition; however, no health centers reported COVID-19 to be a top health condition, though COVID-19 was cited as a significant social issue. Nearly six in ten (58%) health center respondents reported both the social and economic effects of COVID-19 and poverty among the top three most prevalent social issues facing health center patients, while over four in ten (42%) also included lack of jobs as one of the most prevalent. One-third of respondents reported lack of physical activity and poor health education as important issues and smaller shares cited limited education, violence, and lack of housing as concerns (Figure 1).

Health Center Patients, Services, and Financing

Most patients served by health centers in the territories and the FAS are poor. Reflecting higher rates of poverty in the territories, 87% of health center patients had incomes at or below the federal poverty level (FPL) and 98% had incomes at or below 200% FPL in 2020. In comparison, 68% of health center patients in the 50 states and DC had incomes at or below poverty and 91% had incomes at or below 200% FPL (Appendix Table).

In part because of higher poverty, the majority of health center patients in the territories are covered by Medicaid. Across the territories, excluding American Samoa, 62% of health center patients are covered by Medicaid (63% in Puerto Rico and USVI and 50% in the Pacific Island territories, excluding American Samoa) compared to just over 46% in the 50 states and DC. American Samoa does not make individual eligibility determinations for Medicaid and individuals in American Samoa do not enroll in Medicaid. Additionally, as noted above, citizens of the FAS are not eligible for Medicaid unless they are lawfully residing in the U.S. territories or in the U.S. states. Consequently, over eight in ten (81%) health center patients in the FAS are uninsured (Appendix Table).

Health centers provide access to a comprehensive set of primary care services and other key services for the residents of the U.S. territories and the FAS. While all health centers provide primary care and preventive medical services, they also fill in gaps in the health care system, offering a range of other services, including dental, vision, mental health and substance use disorder (SUD), and pharmacy services. Additionally, according to Pacific Islands Primary Care Association (PIPCA), some health centers in the FAS serve as the primary outpatient centers for their respective islands. The array of services provided by each health center differs based on local needs and the health center’s capacity. While the majority of visits provided by all health centers in the territories and FAS are for medical visits, 10% of visits at health centers in Puerto Rico and USVI are mental health and SUD visits, and in the Pacific Island territories and FAS, dental services account for 8% of total health center visits (Table 2).

Health centers in the territories and FAS also provide a range of social and supportive services, both on-site and through referral to other community organizations. Nearly all the health centers that responded to the survey (92%) said they provide transportation services onsite and 83% provide case management services. Smaller shares reported providing food and nutrition services and education services (50% each). Health centers were less likely to report providing job placement, childcare, and housing services on-site (Figure 2).

Federal grant funding and Medicaid make up the large majority of revenues for health centers in the territories. Section 330 grants provide annual support for health center operations, and supplemental Section 330 grants are made available to expand capacity, improve care, and respond to emerging priorities, including COVID-19. Health centers in the territories and FAS rely more heavily on Section 330 funding than health centers in the U.S. states; these grants (excluding COVID-19 supplemental funding) comprised 25% of total revenues for health centers in the territories and FAS in 2020 compared to 14% for health centers in the 50 states and DC. Medicaid is a major source of funding for health centers in Puerto Rico and USVI, accounting for close to 50% of total revenues but is a less significant source of revenue for health centers in the Pacific Island territories. The Freely Associated States do not receive Medicaid funding and therefore most of their funding comes from Section 330 grants (Appendix Table).

Impact of the Pandemic on Health Center Patients and Services

Like health centers in the 50 states and DC, health centers in the territories and FAS saw a decline in the number of patients and visits compared to before the pandemic. Overall, the number of patients served by health centers in the territories and FAS dropped by 12% in 2020 compared to 2019 while the number of patient visits, including both clinic and virtual visits, declined by 17% (Table 2). However, the impact of the pandemic was more severe for health centers in the Pacific Island territories where the number of patients dropped by 31% and patient visits fell by 38%. In Puerto Rico and USVI, the number of patients and visits dropped by 12% and 17%, respectively, while health centers in the FAS saw a slight increase (3%) in the number of patients and the number of visits decreased by less than 1%.

While overall visits declined, health centers in the territories reported an increase in visits for mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) services. Overall, health centers in the territories and FAS reported a 25% increase in mental health visits and a 26% increase in SUD visits during the pandemic (Table 2). The negative effects of the pandemic on mental health as well as the ability to transition mental health and SUD services more easily to virtual visits likely contributed to the increase in visits for these services.

Despite increasing mental health and SUD services during the pandemic, respondents from the Primary Care Associations described ongoing challenges in providing these services. ASPPR noted that the mental health needs of health center patients in Puerto Rico are becoming increasingly complex because of the lingering effects of past natural disasters that have been exacerbated by the pandemic. In the Pacific Island territories and FAS, according to PIPCA, the lack of an adequate referral network complicates treatment for patients with behavioral health conditions who need a broader set of social and supportive services. For example, the dearth of social workers in the territories and especially in the FAS makes it difficult to connect patients with the range of services they need.

Most health centers said they can schedule patient appointments for new patients for various services within two weeks, but four in ten said wait times for appointments had gotten longer since the start of the pandemic. Particularly for SUD, prenatal, and family planning services, 80% or more of responding health centers indicated appointments were available within two weeks, including 20% that said appointments for these services were available on a walk-in basis. Fewer health centers (45%) reported they could schedule medical appointments within two weeks or via walk-in. Despite the overall decline in patient visits, 40% of health centers reported wait times had increased and 40% said wait times had stayed about the same compared to before the pandemic.

Telehealth Services

The use of telehealth services increased dramatically among health centers in the territories in response to the pandemic. Over eight in ten (83%) responding health centers said they currently provide telehealth services, and among those providing telehealth services, 40% said they did not provide any telehealth services prior to the pandemic. All health centers that reported providing new telehealth services during the pandemic indicated they planned to provide some or all of these services on a permanent basis. In 2020, telehealth visits accounted for almost one quarter (24%) of total visits in Puerto Rico and USVI, but just 2% of total visits at health centers in the Pacific Island territories. Telehealth visits were not widespread in the FAS with only 75 total telehealth visits occurring in the FAS in 2020 (Figure 3).

Despite an increasing reliance on telehealth services, health centers in the territories and FAS face numerous challenges to providing virtual visits. Three-quarters of responding health centers cited lack of internet access, including lack of a smartphone or computer or limited data, among patients as a barrier. Inadequate reimbursement and lack of comfort with telehealth technology among both patients and providers were reported as barriers by a third of health centers. In contrast, no health center reported a lack of funding to purchase equipment as a barrier and just 8% said the cost of operating a program or lack of internet access at the health centers was a barrier (Figure 4).

Respondents from the Primary Care Associations for both Puerto Rico and the Pacific Islands echoed the telehealth challenges reported by health centers. ASPPR agreed that health center patients in Puerto Rico face barriers to using telehealth due to a lack of access to internet or a smartphone, noting that patients in rural areas and older patients experience particular barriers. PIPCA also noted that broadband has only recently become available in some of the islands of the FAS and that some islands still face outages during weather events.

COVID-19 Services

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has affected each territory differently, with many of the Pacific Islands remaining free of COVID-19 for the large part of last year, health centers have been important providers of COVID-19 testing and vaccinations. Health centers in all the territories and FAS, except in CNMI, provide regular COVID-19 testing. Health centers are also helping to administer the COVID-19 vaccine. Since January 2021, health centers in the territories have administered around 405,000 vaccine doses, representing about 7% of all vaccine doses administered in the U.S. territories; health centers in the FAS have administered around 55,000 doses, representing 35% of all vaccine doses administered in the FAS.

Health centers are administering the COVID-19 vaccine at multiple sites in their communities. All responding health centers said they administer the vaccine at their clinic sites and majorities also said they provide the vaccine at community sites (70%), and via mobile vans (60%). A smaller share (20%) reported vaccinating individuals at workplaces (Figure 5).

Impact of the Pandemic on Health Center Financing

Health centers in U.S. territories have received over $28 million in COVID-19 related funding in 2020 to assist with COVID-19 prevention, diagnosis, and treatment during the public health emergency (PHE). This COVID-19 funding included automatically awarded rapid response grants to improve COVID-19 testing, purchase personal protective equipment (PPE), and maintain health center capacity generally, as well as funding from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act for the Provider Relief Fund and COVID-19 Uninsured program. In 2020, COVID-19 related funding made up 5% of total revenues in Puerto Rico and USVI, 9% of total revenues in the Pacific Island U.S. territories, and 24% of total revenues in the FAS (Appendix Table). Health centers that responded to the survey reported that these additional funds were very important in offsetting costs associated with purchasing PPE, providing COVID-19 testing and vaccinations, and maintaining general health center capacities, such as services and staffing.

There was also a large increase in Medicaid funding for health centers in the territories from 2019 to 2020. Unlike Medicaid funding for the states and DC, Medicaid funding for the territories is capped, which can put a financial strain on the territories’ health care systems and providers. However, for FY 2020 and FY 2021, Congress appropriated additional federal Medicaid funding for the territories in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, Medicaid funding increased by 22% for health centers in Puerto Rico and USVI, while health centers in the Pacific Island territories experienced an almost 50% increase (Table 3). Health centers in the FAS are not eligible for Medicaid.

The increase in federal COVID-19 relief and Medicaid funds contributed to an increase in overall funding for health centers in the territories and FAS in 2020. Health centers in the FAS saw the largest increase in total funding with revenues increasing 37% (Table 3), while total revenues for health centers in Puerto Rico and USVI increased by 16%. Health centers in the Pacific Island territories experienced a more modest 8% increase in revenues. As the COVID-19 relief funding winds down, some health centers have seen their revenues begin to decrease. Just under half (45%) of responding health centers reported that total revenues decreased from March 2020 to March 2021.

Ongoing Challenges

Even as they meet the immediate challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, health centers in the territories and FAS face several ongoing operational challenges. Despite an increase in staff during the pandemic, over six in ten (64%) responding health centers reported workforce recruitment as a major challenge. Increasing operating costs and inadequate physical space were also cited as major challenges by health centers. These challenges are similar to those facing health centers in the U.S. states. Health centers in the territories and FAS face the additional challenge of operating within a broader health system that is not always able to meet patient needs. Consequently, a majority of health centers (64%) also reported the lack of an adequate referral network for specialty and acute care as a major operational barrier (Figure 6).

Echoing the workforce challenges reported by health centers, Primary Care Associations noted the longstanding challenges with health care provider shortages in the territories and FAS. Provider recruitment and retention are difficult as salaries for providers in the territories are substantially lower than they are for providers in the U.S. even though providers in most territories must be U.S.-licensed. PIPCA reported that the Pacific Island territories face nursing shortages due to licensing requirements. In addition, health centers face challenges retaining providers because they cannot compete with the higher salaries offered by other health care systems in the territories. This is a particular problem in rural areas of Puerto Rico.

What’s Next?

Health centers in the territories and FAS have responded to the coronavirus pandemic by playing an active role in COVID-19 testing and vaccination efforts and by innovating services, including by increasing the availability of telehealth services, to meet patients’ needs. While the COVID-19 threat will likely remain in 2022, health centers will continue to provide access to primary care services and will meet the increased need for mental health and SUD services that surfaced during the pandemic as well as the ongoing needs for certain social and supportive services.

As the COVID-19 relief funding expires, provisions in the Build Back Better Act, passed by the U.S. House, would permanently increase the federal Medicaid cap on funding and the matching rate for the territories. Specifically, the Build Back Better Act would increase the FY 2022 funding amounts for the territories above levels provided in 2020 and 2021 and index future allotments to the percentage increase in overall Medicaid spending. In addition, the federal matching percentage would be permanently increased to 83% for the territories beginning in FY 2022 (Puerto Rico’s match rate would be 76% in FY 2022 before increasing to 83% in FY 2023 and subsequent years). If enacted, the enhanced Medicaid funding provided in the Build Back Better Act will avoid an expected fiscal cliff when the increased funding provided by the American Rescue Plan Act expires.

Enhanced federal grant funding as well as increased Medicaid funding for the territories during the pandemic helped to offset revenue losses from reduced patient utilization and enabled health centers to weather the crisis and continue serving their patients. Stable grant and Medicaid funding for health centers in the territories and FAS will help them to address ongoing and future operational and financial challenges.

Methods

The 2021 Survey of Community Health Centers in the U.S. Territories and Freely Associated States was jointly conducted by KFF and the Geiger Gibson/RCHN Community Health Foundation Research Collaborative at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health.

The survey was fielded from July to September 2021 and was emailed to 33 CEOs of health centers in the US territories and Freely Associated States identified in the 2019 Uniform Data System (UDS). The response rate was 39% with 13 community health center responses from three territories and two FAS.

Interviews were conducted with Primary Care Associations representing the Pacific Islands (Pacific Islands Primary Care Association, known as PIPCA) and the Primary Care Association representing Puerto Rico (Asociación de Salud Primaria de Puerto Rico, known as ASPPR) in August 2021. Questions were asked about challenges faced by community health centers, the impact of COVID-19 on community health centers and their patients, and the role of Medicaid and Section 330 funding.

We used Health Resources and Services Administrations’ (HRSA) Health Center COVID-19 Vaccination data and KFF’s analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) COVID-19 Vaccines Administered data for analysis of vaccinations. These data were pulled on December 2, 2021. For other analyses, we used data from the 2019 and 2020 Uniform Data System (UDS).

Additional funding support for this brief was provided to the George Washington University by the RCHN Community Health Foundation.