Community Health Centers in a Time of Change: Results from an Annual Survey

Health coverage, affordability, and revenue

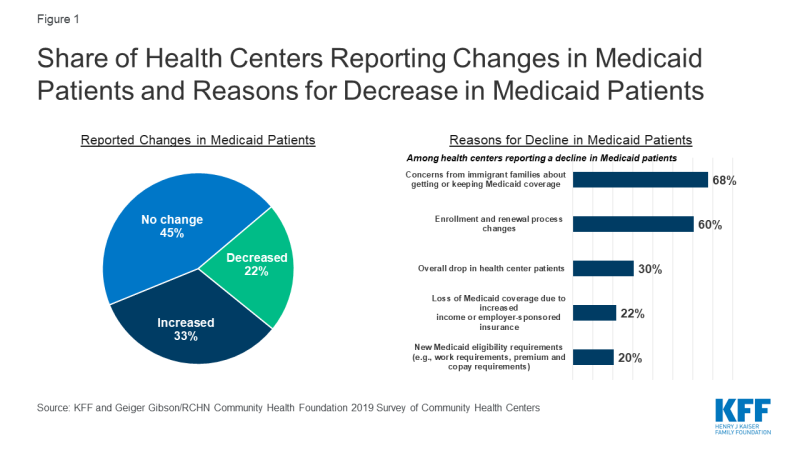

Five years following the ACA coverage expansions, most health centers reported the number of Medicaid patients had increased or stayed the same over the past year. In contrast to national trends showing Medicaid enrollment declines, one-third of health centers said the number of Medicaid patients had increased in the past year while 45% said the number had stayed the same (Figure 1). Health centers serve as an important source of care for Medicaid patients and as they continue to expand their service capacity, some are likely attracting new Medicaid patients.

Figure 1: Share of Health Centers Reporting Changes in Medicaid Patients and Reasons for Decrease in Medicaid Patients

At the same time, one in five health centers said the number of Medicaid patients had declined. Health centers in non-expansion states were more likely to report their Medicaid patients had decreased (28% vs. 19% in Medicaid expansion states, data not shown). Among health centers reporting a decline, the most commonly reported reason for the decline (68%) was concerns among immigrant families about applying for or keeping Medicaid for themselves or their children. Nearly as common, six in ten health centers attributed the decline to changes in enrollment and renewal processes that make it more difficult for patients to obtain or keep Medicaid coverage, while three in ten cited an overall drop in the number of health center patients. The reasons cited for the decline differed by Medicaid expansion status and urban/rural status. Health centers in Medicaid expansion states were significantly more likely to attribute decreases in Medicaid patients to patients gaining jobs and losing Medicaid coverage due to increased income and/or employer-sponsored insurance (30% vs. 7% for non-expansion states, Appendix Table 1). Urban health centers were significantly more likely than rural health centers to report that concerns from patients in immigrant families about applying for or keeping Medicaid for themselves or their children explained the drop in Medicaid numbers (77% vs. 46%); while rural health centers were significantly more likely to cite declines in overall health center patient numbers (46% vs. 23% for urban) as a reason.

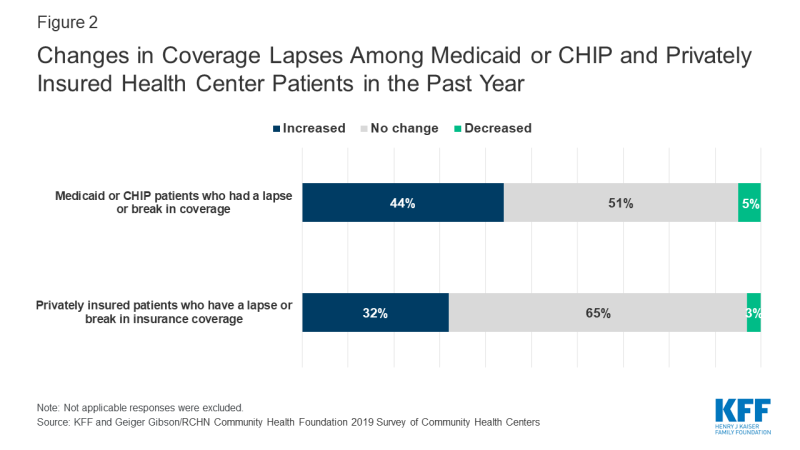

Health centers also reported an increase in coverage lapses among Medicaid and CHIP patients as well as those with private insurance. Over four in ten (44%) health centers reported an increase in coverage lapses for their Medicaid/CHIP patients, while a slightly smaller share of health centers (32%) reported coverage lapses among privately insured patients had increased (Figure 2). There are a number of reasons why people may experience a lapse or break in coverage. For Medicaid patients, the coverage lapses may stem from difficulties in renewing coverage. For privately insured patients, a break in coverage may reflect a change in employment and temporary loss of coverage or an inability to afford the monthly premium, among other reasons.

Figure 2: Changes in Coverage Lapses Among Medicaid or CHIP and Privately Insured Health Center Patients in the Past Year

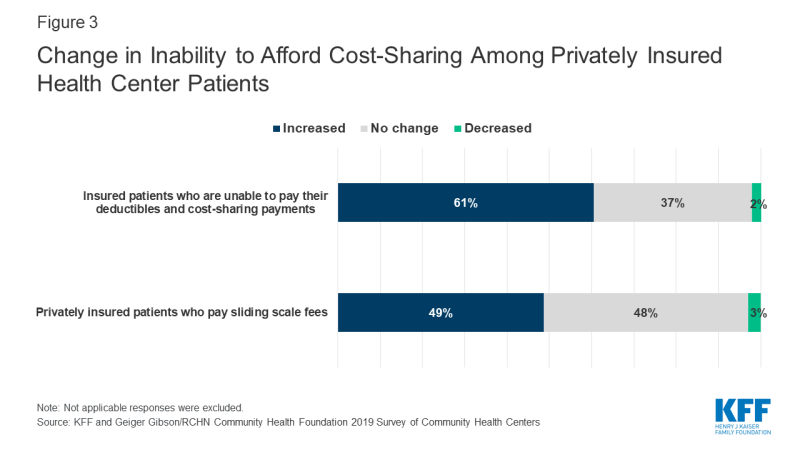

Health centers reported their privately insured patients face increasing challenges affording coverage. More than six in ten health centers (61%) reported an increase in the past year in the percentage of insured patients who are unable to pay their deductibles and cost-sharing payments, and nearly half (49%) reported an increase in privately insured patients paying sliding scale fees (Figure 3). Health center patients qualify for sliding fee scale payments based on their income. An increase in the number of patients with private insurance who pay the sliding fee scale in lieu of the health plan’s copayments or other cost sharing suggests those payments are unaffordable to the individual.

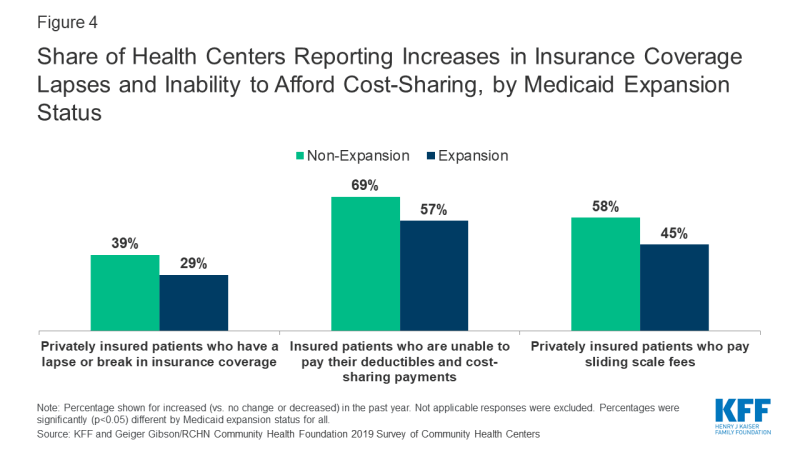

Health centers in non-expansion states were more likely to report affordability challenges for their privately insured patients. Health centers in non-expansion states were significantly more likely than health centers in Medicaid expansion states to report increases in the past year in patients’ inability to afford cost-sharing payments and in the percentage of privately insured patients paying sliding-scale fees (Figure 4). These differences may be explained, in part, by the higher rates of marketplace coverage among low-income patients in non-expansion states. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, low-income individuals with incomes above 100% of the poverty level may enroll in marketplace coverage, but will face cost sharing requirements that may be difficult for them to afford. Rural health centers were significantly more likely than urban health centers to report an increase in privately insured patients paying sliding scale fees (55% vs. 44%).

Figure 4: Share of Health Centers Reporting Increases in Insurance Coverage Lapses and Inability to Afford Cost-Sharing, by Medicaid Expansion Status

Health centers’ financial situation remains strong, with most reporting improved or stable financial factors in the past year; however, some health centers reported decreases in key revenue sources. Similar to findings on patient coverage, most health centers continue to benefit financially from the ACA coverage expansions and enhanced federal health center funding. Over half (51%) of health centers reported an increase in federal grant funding from annual appropriated funding, the Community Health Center Fund as well as from targeted grant funding, and three in ten reported an increase in Medicaid revenue (Figure 5). At the same time, a growing share of health centers reported a decrease in Medicaid revenue. In 2019, similar to the share of health centers reporting a drop in Medicaid patients, 23% of health centers reported a decline in Medicaid revenue compared to just 15% in 2018.1 As health centers’ single largest source of operating revenue (44% in 2018),2 Medicaid revenue declines may carry implications for health centers’ ability to add service sites, hire staff, and expand the scope of care they provide. Additionally, over three in ten health centers that received Title X grant funding reported a decrease in their funding in the past year.

Addressing social determinants of health

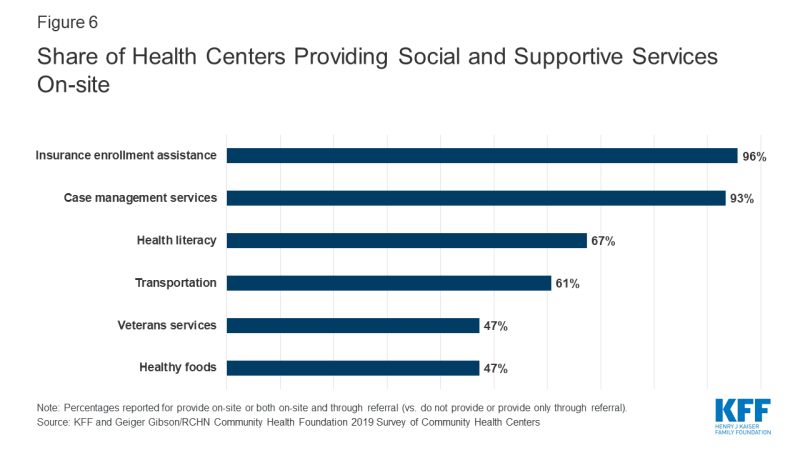

Health centers provide a range of social and supportive services aimed at addressing social determinants of health. Nearly all health centers reported providing insurance assistance services and case management services on-site (96% and 93%, respectively), and over six in ten health centers said they provided health literacy services (67%) and transportation services (61%) on-site (Figure 6). Nearly half (47%) reported providing healthy foods and veterans’ services. The provision of certain social and supportive services differed by Medicaid expansion status and between urban and rural health centers (Appendix Table 1). Health centers in non-expansion states were significantly more likely to provide veterans’, education, and agricultural worker support services on-site, while health centers in Medicaid expansion states were significantly more likely to provide insurance enrollment assistance services on-site. Urban health centers were significantly more likely to provide on-site transportation, SNAP, WIC, or other nutritional assistance, and refugee services, while rural health centers were significantly more likely to provide on-site agricultural worker support and veterans’ services (Appendix Table 1).

Potential implications of Medicaid work requirements

As of March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) had approved Medicaid Section 1115 waivers to implement work/community engagement requirements for ten states and ten state proposals are pending.3 At the same time, federal courts have set aside four approvals (Arkansas, Kentucky, Michigan, and New Hampshire) and work requirements in another four states with approved waivers—Arizona, Ohio, South Carolina, and Wisconsin—have not yet been implemented. Indiana, which has implemented work requirements, announced that it will temporarily suspend enforcement of the requirements pending the outcome of a legal challenge.4 A work demonstration was in effect and moving forward in Utah but was suspended on April 2, 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.5 However, the future of these demonstrations may be in doubt following a ruling by a federal appeals court upholding a lower court’s decision striking down the work requirements in Arkansas. Before Arkansas’s work requirements program was halted by the court, over 18,000 Medicaid enrollees lost coverage; over 95% of those losing coverage either met the requirements or qualified for an exemption.6

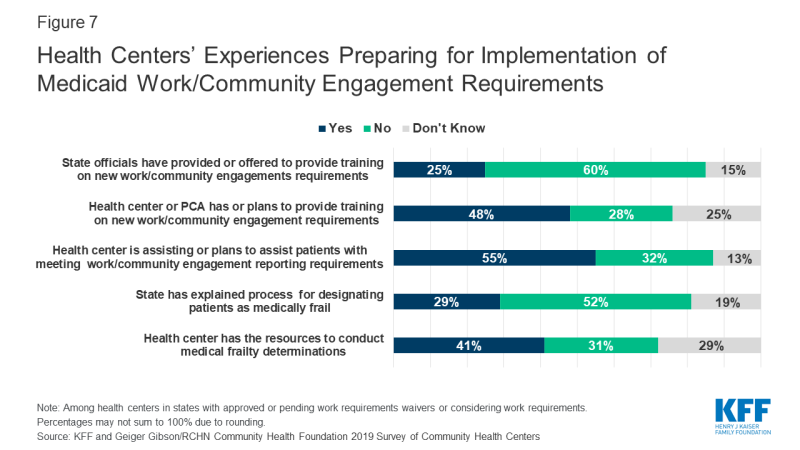

Survey findings revealed a great deal of confusion and lack of information about the status of work requirement waivers and how those work requirements would be implemented. In states with an approved or pending waiver at the time of the survey, one in five respondents incorrectly identified the status of the state’s approved or pending waiver or indicated that they did not know if the state had or was considering a waiver. Among the survey respondents who correctly said that their state had an approved or pending waiver to implement Medicaid work/community engagement requirements or was considering developing a waiver, six in ten said their state had neither provided nor offered to provide training on the work requirements (Figure 7). Despite this lack of training from the state, nearly half (48%) of health centers reported they or their Primary Care Association (PCA) had provided or planned to provide training to their employees.

Most health centers indicated a desire to help patients with work reporting requirements and with obtaining exemptions; however, some health centers said they lacked the resources to do so. While over half (55%) of health centers in states with an approved or pending waiver said they were assisting or planned to assist patients with the new reporting requirements, more than three in ten (32%) said they were not providing or did not plan to provide the assistance (Figure 7). Most states include an exemption from work requirements for medically frail individuals; medical frailty determinations must be made by medical professionals. Although 52% of health center respondents reported state officials had not explained the process for determining patients as medically frail, 41% said they had the resources to conduct the determinations. However, reflecting the resource burden of making medical frailty determinations, six in ten (59%) said they did not have the resources or did not know if they had the resources to make these determinations.

Figure 7: Health Centers’ Experiences Preparing for Implementation of Medicaid Work/Community Engagement Requirements

Health centers perceive that their patients who are not currently working face many barriers to work. All health centers, regardless of their state’s waiver status, were asked about potential barriers to working among their adult, non-elderly, and non-disabled Medicaid patients who are not currently working. They reported a mix of health and mental health-related barriers as well as geographic and economic barriers to work. Over seven in ten health centers reported that many of their patients faced substance use disorders, acute or chronic mental health conditions, and acute or chronic physical health conditions (Appendix Table 1). Similar shares of health centers noted other barriers, such as child caring responsibilities, lack of transportation to jobs, or inadequate skills or education. Compared to health centers in rural areas, urban health centers were more likely to report as barriers preventing patients from working a mismatch between available jobs and patients’ skills and education and family caretaking responsibilities, while rural health centers were more likely than their urban counterparts to report a lack of jobs in the community, and the seasonal nature of many jobs.

Health centers also indicated their patients would likely face many barriers that would make it difficult for them to report work activity. In addition to confusion over reporting rules and deadlines, over half of health centers (57%) reported that lack of access to a computer would be a barrier for many patients and nearly half (47%) reported not having internet service would be a barrier for many patients, which would prevent them from being able to report work activity by phone or online, as required by several states (Appendix Table 2).

Participation in the Title X program and ability to accept new family planning patients

New rules governing the Title X family planning program went into effect on July 15, 2019, imposing new restrictions on grantee activities. These restrictions include blocking participation of program providers that also offer abortion services, barring staff from fully counseling pregnant patients about all options, and requiring mandatory referral of pregnant women for prenatal care regardless of patient choice. Before the restrictions took effect and as of June 2019, 4,008 Title X clinics were in operation. By December 20, 2019, all 410 Planned Parenthood health centers had withdrawn from the program, and an additional 631 Title X clinics, including some community health centers, were no longer participating in Title X.7 The decision to stop participating in Title X means the loss of funding to support family planning services at these clinics and health centers.

As of July 2019, a quarter of health centers reported participating in the Title X program, though that number may have changed following implementation of more restrictive rules. The share of health centers reporting receiving Title X funding was similar to the 26% who said they received Title X funding in 2017.8 Since the survey, which was conducted before the new rules went into effect, a significant number of health centers may have dropped their Title X participation, although a count is not available. Some health centers may perceive a conflict between the Title X counseling and referral ban and its physical and financial separation requirements and health centers’ patient care obligations under their funding authority (Section 330 of the Public Health Service Act).9,10

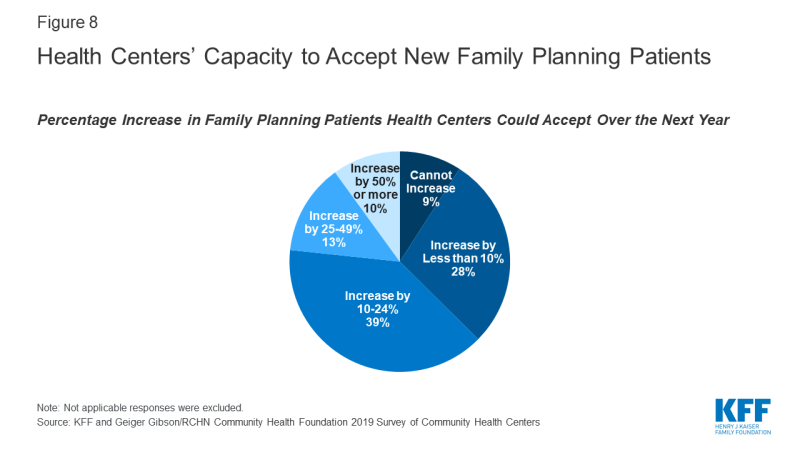

Health centers reported limited capacity to accept new family planning patients. With hundreds of clinics, including health centers, leaving the Title X program and their ability to serve family planning patients diminishing due to loss of funding, the need for alternative sources of care is expected to rise. Family planning services are part of the comprehensive primary care package that all health centers must furnish under Section 330.11 However, many health centers have limited capacity to expand these services. Over one-third (37%) of health centers reported either they could not expand patient load or they could expand by less than 10% with current staffing and clinic space; another 39% said they could increase the number of family planning patients by less than 25% (Figure 8). Despite limited capacity at some health centers, over one in five (23%) said they could expand capacity by 25% or more, including one in ten who said they could increase the number of family planning patients by 50% or more.

Challenges facing health centers

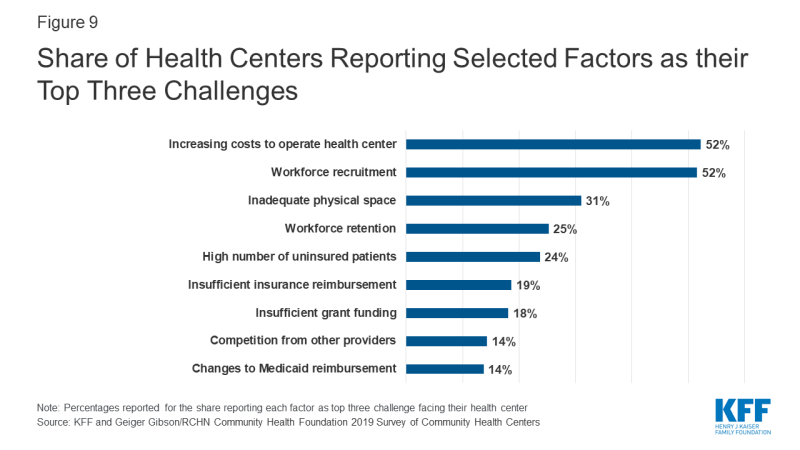

Despite ongoing policy challenges, health centers were more likely to report operational issues as top challenges. Over half of health centers (52%) cited workforce recruitment and increasing costs to operate their health center as top challenges, while three in ten (31%) cited inadequate physical space as a top challenge (Figure 9). A quarter of health centers reported workforce retention (25%) and high numbers of uninsured patients (24%) as major challenges. Health centers in Medicaid expansion states were more likely than health centers in non-expansion states to report workforce recruitment as a top-three challenge (55% vs. 43%), while health centers in non-expansion states were more likely than those in expansion states to report high numbers of uninsured patients as a top-three challenge (45% vs. 15%, Appendix Table 1). Rural health centers also face provider shortages and were significantly more likely to report workforce recruitment as a top-three challenge (60%) compared to urban health centers (45%). These ongoing challenges, particularly the workforce and financial challenges, are likely to be exacerbated during the current COVID-19 crisis as frontline workers get sick and others must take time off to care for children and other family members, and as health centers face potentially precipitous declines in patient care revenue.

Discussion

As federal policymakers turn to health centers during this time of crisis, they will play an important role in providing access to COVID-19 testing as well as ongoing primary care services for low-income, medically underserved communities. However, even as health centers continue their historic growth brought about by the ACA that may position them well to respond to the crisis, some have encountered limits on their ability to meet the needs of their patients because of recent policy changes, especially those that have resulted in recent declines in Medicaid coverage. While many states and the federal government have temporarily suspended some policies that create barriers to enrolling in Medicaid or to maintaining Medicaid coverage during the emergency, the reinstatement of these policies after the immediate emergency ends could make it harder for health centers to serve their communities in the longer term.

Through coronavirus response legislation, the federal government directed an initial $100 million to health centers12 and later directed over $1.3 billion in emergency grants to health centers to enable them to continue serving their patients during the crisis, and funded the Community Health Center Fund through November 2020.13 Yet, the economic upheaval from this pandemic is likely to persist long after the threat from the virus diminishes. While over half of health centers reported that federal grant funding had increased in the past year, the failure of Congress to pass a long-term extension of the Community Health Center Fund threatens to jeopardize the stable funding health centers have experienced for the past decade. The importance of stable future funding will be even greater in the aftermath of the pandemic as health centers seek to resume normal operations.

| Methods |

| The 2019 Survey of Community Health Centers was jointly conducted by KFF and the Geiger Gibson/RCHN Community Health Foundation Research Collaborative at George Washington University’s Milken Institute School of Public Health. The survey was administered in partnership with the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC). The survey was fielded from May to July 2019 and was emailed to 1,342 CEOs of federally-funded health centers in the 50 states and the District of Columbia (DC) identified in the 2017 Uniform Data System (UDS). The response rate was 38%, with 511 responses from 49 states and DC.

The survey data were weighted using 2017 UDS variables for total health center patients, the percentage of patients reported as racial/ethnic minorities, and total revenue per patient. Survey findings are presented for all responding health centers and responses were analyzed using chi-squared tests to compare responses between health centers in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states and14 health centers in rural and urban locations (based on a UDS variable).State Medicaid expansion status was assigned as of the survey fielding period. |