Introduction

This report provides data on donor government funding for family planning activities in low- and middle-income countries in 2020, the most recent year available, as well as trends over time. It is part of an effort by KFF that began after the London Summit on Family Planning in 2012 and includes data from all 30 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), as well as non-DAC members where data are available.8 Data are collected directly from donors and supplemented with data from the DAC. Direct data collection was carried out for ten donor governments that account for 98% of total funding for family planning. Both bilateral assistance and core contributions to UNFPA are included. For more detail, see methodology.

Findings

Bilateral Funding

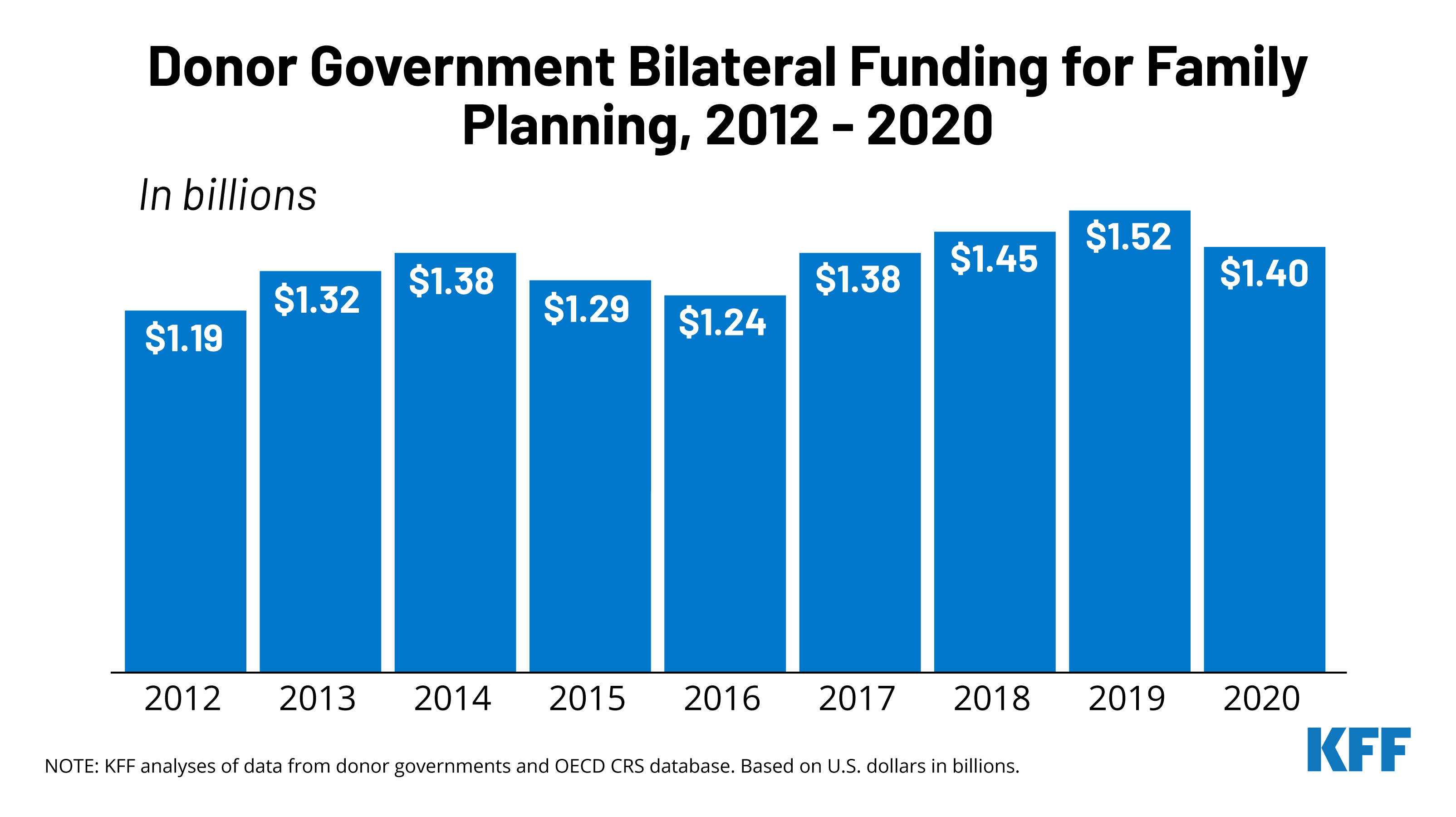

In 2020, donor governments provided US$1.40 billion in bilateral funding for family planning activities (see Figure 1, Table 1, & Appendix), a decline of US$114 million compared to the 2019 level (US$1.52 billion).1 The decline in 2020 followed three years of increases, which, in 2019, resulted in the highest level of funding since the London Summit in 2012.

The decline in 2020 was largely due to decreased funding from the U.K., the world’s second largest donor. It is important to note, however, that the U.K. decline was due to a complex set of factors including the timing of disbursements (funding increased significantly in 2019, but then returned to almost prior year levels in 2020) and the overall decline in ODA resulting from the effect of COVID-19 on GNI.2

Among the ten donors for which direct data collection was conducted, three increased funding in 2019 (Canada, France, and Sweden), three remained essentially flat (Australia, Netherlands, and U.S.), and four decreased (Denmark, Germany, Norway, and U.K.). These trends were the same after adjusting for inflation and exchange rate fluctuations, except for the Netherlands, which increased in currency of origin.

The U.S. was the largest donor to bilateral family planning efforts in 2020, accounting for 42% of donor government funding (see Figure 2). Despite a decline, the U.K. remained the second largest donor (19%) followed by the Netherlands (14%), Sweden (9%), and Canada (7%).

Donor government funding for family planning has generally risen since the London Summit in 2012, although totals have fluctuated over the period. Funding in 2020 (US$1.40 billion) was approximately US$215 million above the 2012 level (US$1.19 billion). In 2020, six donors provided higher funding than in 2012, including Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the U.K. Since funding from the U.S., which has been the largest donor each year over the period, has been relatively flat, the overall trends have largely been driven by the other donors (see Figure 3).

Donor Contributions to UNFPA

While the majority of donor government assistance for family planning is provided bilaterally, donors also provide support for family planning activities through contributions to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Most of UNFPA’s funding is from donor governments, which provide funding in two ways: 1) donor directed or earmarked contributions for specific activities (e.g. donor contributions to the UNFPA Supplies), which are included as part of bilateral funding above; and 2) general contributions to “core” activities that are untied and meant to be used for both programmatic activities (e.g. family planning, population and development, HIV/AIDS, gender, and sexual and reproductive health and rights) and operational support as determined by UNFPA.9

In 2020, the donor governments profiled provided US$411.7 million in core contributions to UNFPA, an increase of more than US$40 million compared to the 2019 level (US$367.6 million). The increase was largely attributable to Germany, which more than doubled its core contribution (from US$37.0 million in 2019 to US$78.8 million in 2020), mostly in support of UNFPA’s efforts to address the impacts of COVID-19.10 In addition to Germany, one other donor increased funding (Sweden), while five remained flat (Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and the U.K.), and two declined (Denmark and Norway); these trends were the same after adjusting for inflation and exchange rate fluctuations, except for Norway, which remained flat in currency of origin.

The ranking of donor contributions to UNFPA differs from that of their bilateral family planning funding. Germany provided the largest core contribution to UNFPA in 2020 (US$78.8 million), followed by Sweden (US$65.9 million), Norway (US$55.1 million), the Netherlands (US$36.8 million), and Denmark (US$34.1 million), (see Figure 4 and Table 2). Three donors – Denmark, Germany, and Norway – provided larger contributions to UNFPA’s core resources than their total bilateral funding for family planning.

Due to the Trump administration’s decision to invoke the Kemp-Kasten amendment to withhold funding – both core and non-core - from UNFPA, the U.S. did not provide a contribution to UNFPA between 2017-2020. The Biden Administration has moved to restore funding, which is expected in 2021. Still, these amounts, and historical UNFPA contributions, place the U.S below other donors as the U.S. directs almost all of its support for family planning through bilateral channels.

Looking Ahead

Donor government funding decisions for 2020 largely occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the decline in family planning funding in 2020 was partially due to the impact of COVID-19 on the U.K. GNI. Whether this trend continues for the U.K. or other donor governments in 2021 and beyond will largely depend on the trajectory of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly the rollout of vaccinations globally, as the pandemic put significant stresses on both donor and recipient country budgets as well as the delivery of family planning services globally.11 At the same time, funding from the U.S. could potentially increase in 2021 as the Biden Administration requested additional resources, and Congress has indicated it may support an increase (although, final funding decisions have not been made). Given that the U.S. is the largest donor to global family planning efforts, any changes would have an outsized impact on the overall amount and trends over time.

Methodology

Bilateral and multilateral data on donor government assistance for family planning (FP) in low- and middle-income countries were collected from multiple sources. The research team collected the latest bilateral assistance data directly for 10 governments: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States during 2021. Data represent the fiscal year 2020 period. Direct data collection from these donors was desirable because they represent the preponderance of donor government assistance for family planning and the latest official statistics – from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Creditor Reporting System (CRS) (see: http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/data) – which are from 2019 and do not include all forms of international assistance (e.g., funding to countries such as Russia and the Baltic States that are no longer included in the CRS database). In addition, the CRS data may not include certain funding streams provided by donors, such as FP components of mixed-purpose grants to non-governmental organizations. Data for all other OECD DAC member governments – Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, the European Union, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland – which collectively accounted for approximately 2 percent of bilateral family planning disbursements, were obtained from the OECD CRS and are from calendar year 2019.

For purposes of this analysis, funding was counted as family planning if it met the OECD CRS purpose code definition: “Family planning services including counselling; information, education and communication (IEC) activities; delivery of contraceptives; capacity building and training.” Where it was possible to identify funding amounts, family-planning-related activities funded in the context of other official development assistance sectors (e.g. education, civil society) are included in this analysis. Project-level data were reviewed for Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden to determine whether all or a portion of the funding could be counted as family planning. Family-planning-specific funding totals for the United States were confirmed through communication with government representatives. Funding attributed to Australia and the United Kingdom is based on a revised Muskoka methodology as agreed upon by donors at the London Summit on Family Planning in 2012. Funding totals presented in this analysis should be considered preliminary estimates based on data provided by representatives of the donor governments who were contacted directly.

It was difficult in some cases to disaggregate bilateral family planning funding from broader population, reproductive and maternal health totals, as the two are sometimes represented as integrated totals. In addition, family-planning-related activities funded in the context of other official development assistance sectors (e.g. education, civil society) have in the past remained largely unidentified. For purposes of this analysis, we worked closely with the largest donors to family planning to identify such family-planning-specific funding where possible. In some cases (e.g. Canada), specific FP percentages were recorded for mixed-purpose projects. In other cases, it was possible to identify FP-specific activities by project titles in languages of origin, notwithstanding less-specific financial coding. In still other cases, detailed project descriptions were analyzed (see Appendix for detailed data table).

Bilateral funding is defined as any earmarked (FP-designated) amount and includes family planning-specific contributions to multilateral organizations (e.g. non-core contributions to UNFPA Supplies). UNFPA contributions from all governments correspond to amounts received during the 2020 calendar year, regardless of which contributor’s fiscal year such disbursements pertain to.

With some exceptions, bilateral assistance data were collected for disbursements. A disbursement is the actual release of funds to, or the purchase of goods or services for, a recipient. Disbursements in any given year may include disbursements of funds committed in prior years and in some cases, not all funds committed during a government fiscal year are disbursed in that year. In addition, a disbursement by a government does not necessarily mean that the funds were provided to a country or other intended end-user. Enacted amounts represent budgetary decisions that funding will be provided, regardless of the time at which actual outlays, or disbursements, occur. In recent years, most governments have converted to cash accounting frameworks, and present budgets for legislative approval accordingly; in such cases, disbursements were used as a proxy for enacted amounts.

For the U.S., funding represents final, Congressional appropriations (firm commitments that will be spent) to the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), rather than disbursements, which can fluctuate from year-to-year due to the unique nature of the U.S. budget process (unlike most other donors, U.S. foreign assistance funding may be disbursed over a multi-year period). U.S. totals also include some funding originally appropriated by Congress for UNFPA that is transferred to the USAID family planning & reproductive health (FP/RH) account due to specific provisions in U.S. law including the Kemp-Kasten amendment (see KFF “UNFPA Funding & Kemp-Kasten: An Explainer”). Prior reports presented disbursements. For this report, all prior-year amounts have been changed from disbursements to appropriations. This change in methodology does not alter the overall trend in total funding from donor governments over time.

UNFPA core contributions were obtained from United Nations Executive Board documents. UNFPA estimates of total family planning funding provided from both core and non-core resources were obtained through direct communications with UNFPA representatives. Other than core contributions provided by governments to UNFPA, un-earmarked core contributions to United Nations entities, most of which are membership contributions set by treaty or other formal agreement (e.g., United Nations country membership assessments), are not identified as part of a donor government’s FP assistance even if the multilateral organization in turn directs some of these funds to FP. Rather, these would be considered as FP funding provided by the multilateral organization, and are not considered for purposes of this report.

The fiscal year period varies by country. The U.S. fiscal year runs from October 1-September 30. The Australian fiscal year runs from July 1-June 30. The fiscal years for Canada and the U.K. are April 1-March 31. Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden use the calendar year. The OECD uses the calendar year, so data collected from the CRS for other donor governments reflect January 1-December 31. Most UN agencies use the calendar year and their budgets are biennial.

All data are expressed in US dollars (USD). Where data were provided by governments in their currencies, they were adjusted by average daily exchange rates to obtain a USD equivalent, based on foreign exchange rate historical data available from the U.S. Federal Reserve (see: http://www.federalreserve.gov/) or in some cases from the OECD. Data obtained from UNFPA were already adjusted by UNFPA to represent a USD equivalent based on date of receipts.