The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

Key Findings

- The latest KFF COVID-19 Monitor finds that fatigue and frustration dominate the public’s mood as the U.S. nears the pandemic’s two-year anniversary. While partisans have often been split in their pandemic attitudes, roughly three in four Democrats, independents, and Republicans say they feel “tired” and “frustrated,” and similar shares say they think it is likely that most people in the U.S. will eventually get infected with COVID-19. Partisans do divide, however, on whether the pandemic is the most important issue facing the country, with about half of Democrats choosing COVID-19 as the most important among 6 different issues and a similar share of Republicans choosing inflation as the top issue.

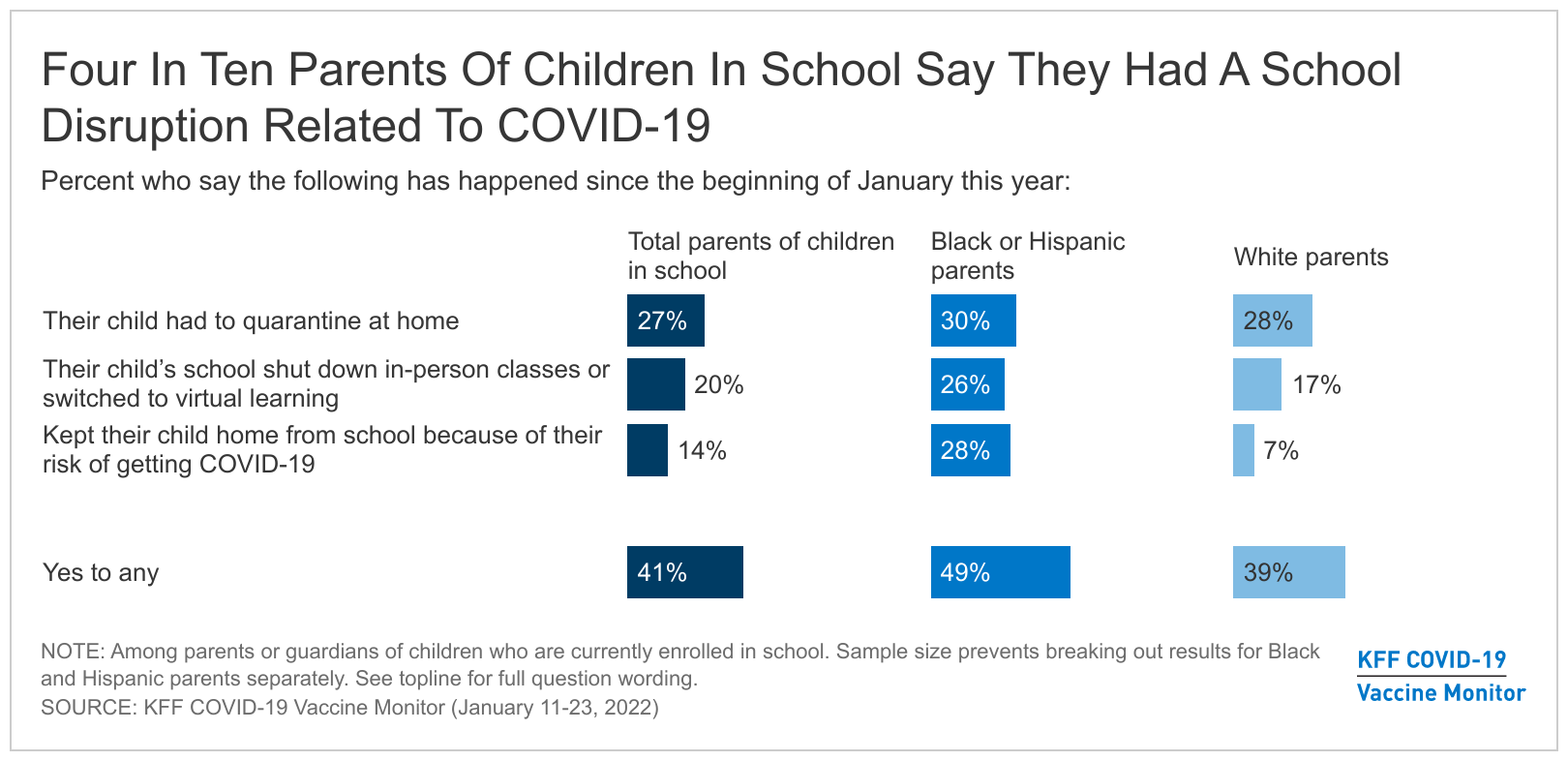

- The public overall says that compared to previous waves of the virus, they are now “more worried” about the impact of the omicron surge on the U.S. economy and on their local hospitals, but “less worried” about the impact in their own personal lives. Notably, however, Black and Hispanic adults and those with lower incomes report higher levels of worry than their counterparts when it comes to missing work due to COVID-19 or becoming seriously ill or hospitalized, reflecting the increased burden the pandemic has placed on people of color over the past two years.

- While many vaccinated people have become infected with the omicron variant, a majority of the public (62%) continue to see the fact that most vaccinated people who get COVID-19 do not require hospitalization as a sign that the vaccines are working. However, the share who see breakthrough infections as a sign that the vaccines are not working has increased slightly since September (from 26% to 34%).

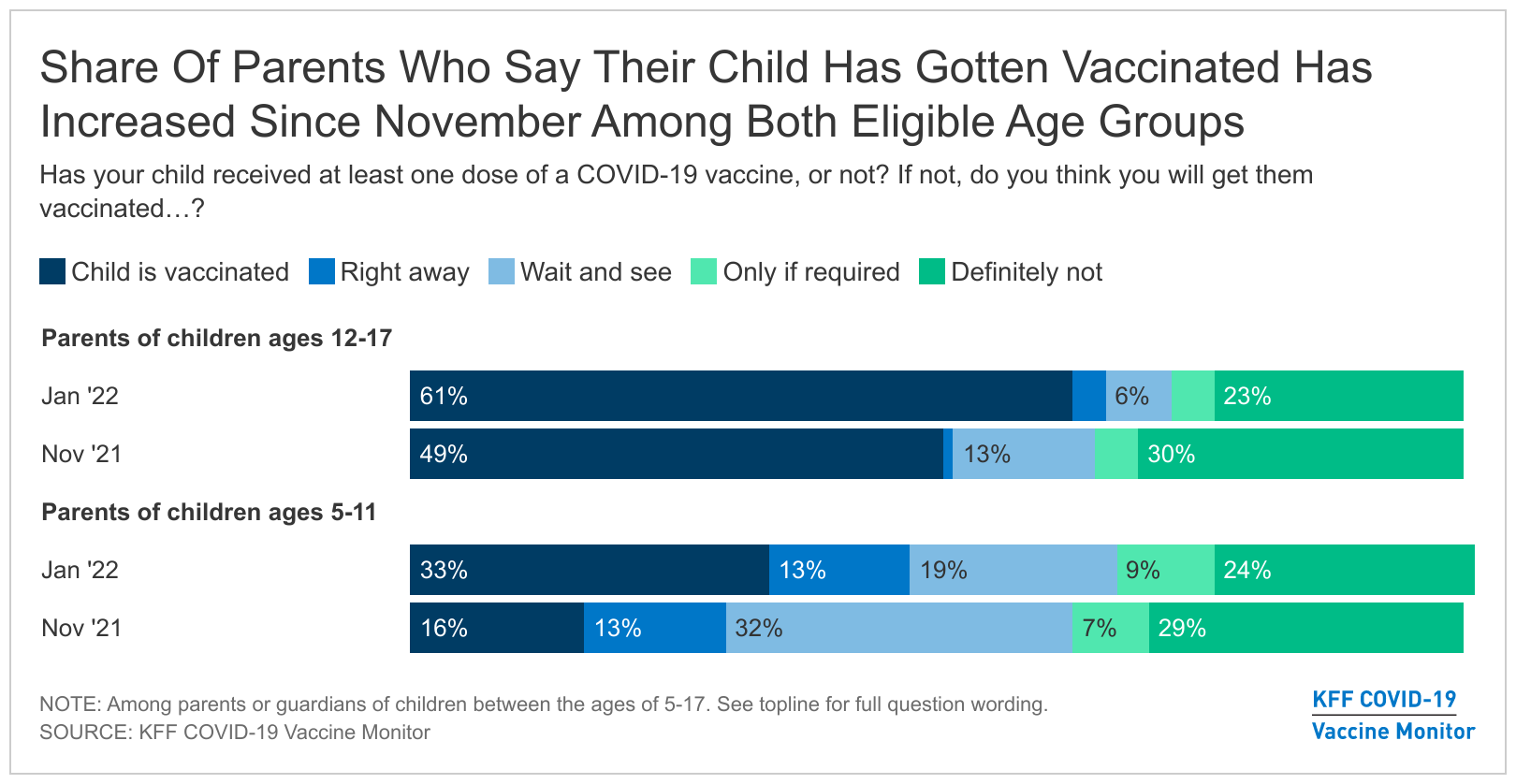

- After holding relatively steady for several months, vaccine uptake inched up in January, with 77% now saying they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (up from 73% in November 2021). This movement seems to have come from a chipping away at the shares who say they will get vaccinated right away, will “wait and see” or will get vaccinated only if required. The share saying they will “definitely not” get vaccinated currently stands at 14% and has not moved in a statistically significant way since December 2020.

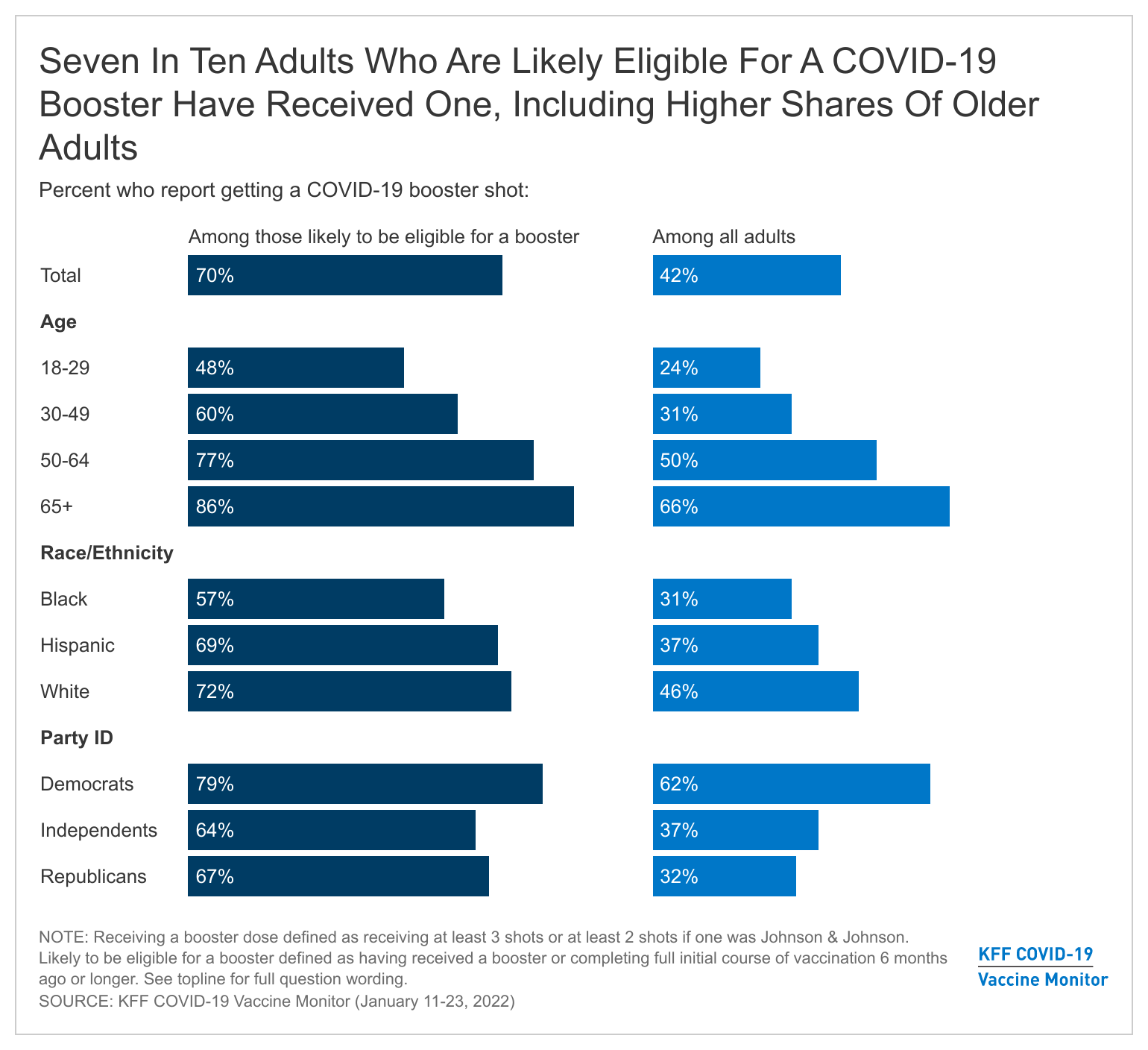

- With the CDC now recommending that all eligible adults get a COVID-19 booster shot, we find that about four in ten (42%) of all adults say they have received a booster dose, a third (34%) have received at least one vaccine dose but are not boosted, and 22% remain unvaccinated. Among the population likely to be booster-eligible (those who either received a booster or completed a full initial course of vaccination 6 months ago or longer), seven in ten have gotten a booster.

- Gaps in booster uptake are mirroring early gaps in initial vaccination uptake, with adults 65 and older (66%) and Democrats (62%) among the most likely to have received a booster and Black and Hispanic adults lagging behind White adults in booster uptake (31%, 37%, and 46%, respectively). Among those who are vaccinated but not boosted, four in ten (39%) say they want to get a booster as soon as they can, however a similar share say they will either definitely not get a booster (19%) or only do so if required (22%).

- Nearly one-quarter of adults (23%) now say they’ve tested positive for COVID-19 at some point, including 8% who say they’ve tested positive in the past month. Among those who tested positive in the past month, 16% say their positive result was on an in-home test only, which is unlikely to be recorded in official COVID-19 case counts. Difficulty accessing COVID-19 tests is likely further contributing to an undercount of cases.

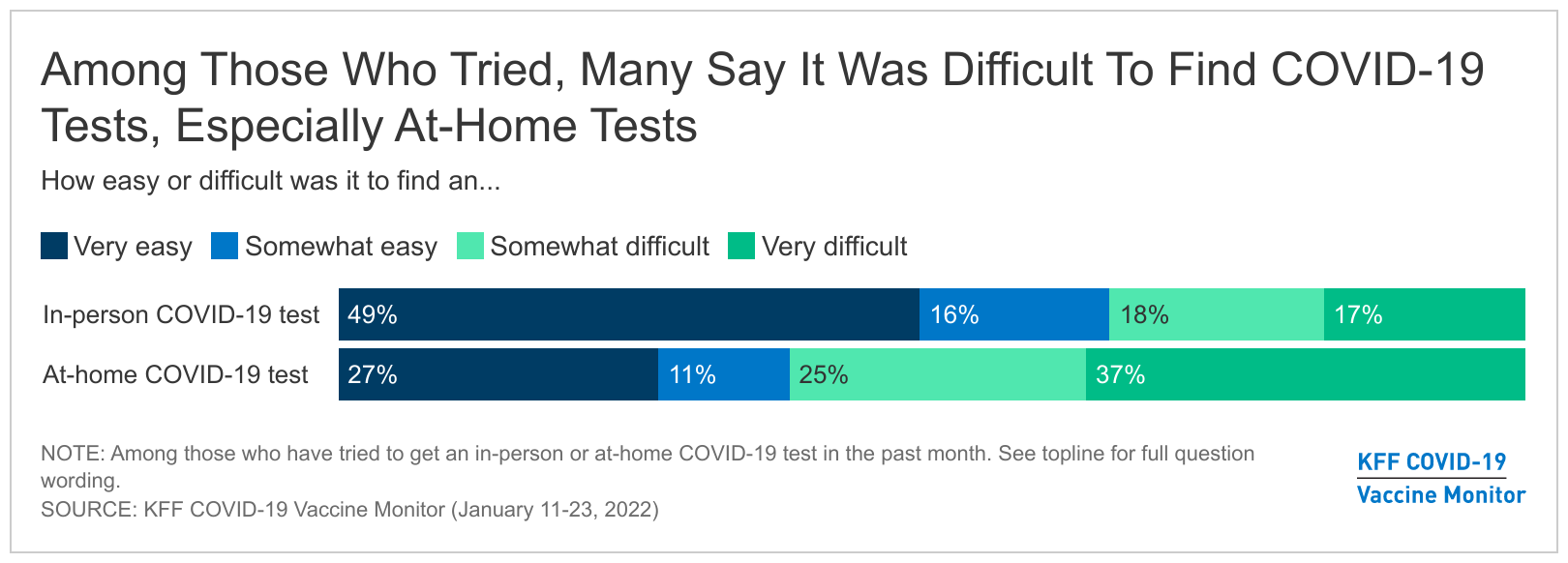

- Amid the omicron surge, about six in ten of those who tried to purchase an at-home COVID-19 test say the tests were difficult to find, and one-third (35%) of those who tried to find an in-person test similarly report difficulty. Overall, nearly a quarter (23%) of all adults say they tried to find either type of test and faced difficulty. More broadly, about half of adults say there are not enough COVID-19 tests available in their local area for those who want them. In addition, while about eight in ten are confident the results of COVID-19 tests at a medical facility or testing site are usually accurate, just over half (54%) are similarly confident in the accuracy of home tests.

- About half of adults say the FDA deserves at least a fair amount of blame for the limited availability of tests, while about four in ten assign blame to each President Joe Biden and the test manufacturers. President Biden announced on January 14th that Americans could order free at-home tests beginning on January 19th, while the survey was still in the field.

- Around one in five adults (19%) report they’ve personally had difficulty in the past three months figuring out whether they needed to isolate or limit their normal activities due to a COVID-19 exposure, positive test, or symptoms. This is even higher among those who say they tested positive for COVID-19 in the last month (38%) and those who reported difficulty finding a COVID-19 test (37%).

Mood Of The Country

Nearly two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, the public’s mood is dominated by fatigue and frustration. About three in four adults including majorities across age, gender, race and ethnicity, and income groups say that “tired” and “frustrated” describe how they feel about the current state of the pandemic in the U.S., while about four in ten each say they are “optimistic” or “angry” and three in ten say they feel “confused.”

While previous KFF research has shown that most attitudes toward COVID-19 tend to diverge along partisan lines, “tired” and “frustrated” are the dominant emotions expressed across partisans, with at least seven in ten Democrats, independents, and Republicans saying each word describes how they feel about the current status of the pandemic.

Despite feeling fatigued about the current state of the pandemic, about a third of adults (34%) continue to see the pandemic as the biggest problem facing the country right now, ranking slightly ahead of rising prices due to inflation (28%). About one in ten say climate change (9%) and racial inequality (8%) are the biggest problems facing the country, while 6% choose crime and 5% choose product shortages due to supply chain issues as the country’s biggest problems. Partisans have differing views as a half of Democrats (51%) say the pandemic is the biggest problem, while a similar share of Republicans (44%) cite inflation. Among independents, about equal shares say the pandemic (28%) and inflation (30%) are the biggest problem facing the United States right now.

Along with feelings of fatigue and frustration, the public overall seems resigned to the idea that COVID-19 infection is inevitable for most people. Three in four adults (77%) think that most people in the U.S. will eventually get COVID-19, including majorities across gender, age, income, and racial and ethnic groups. Similar shares across partisanship and vaccine status also say this is inevitable.

In addition, six in ten (62%) of those who have never tested positive for COVID-19 think it is “very likely” or “somewhat likely” they will become infected in the next year, including two-thirds of those who are vaccinated and 45% of those who are unvaccinated and also have never tested positive.

Impact Of Omicron

Omicron’s Impact On Worries

With the omicron variant of COVID-19 spreading across the country, about four in ten adults (42%) say they are “very” or “somewhat” worried that they will become infected with the new variant. The share who are worried about the virus’ impact is somewhat lower, with about a third saying they are worried they will become seriously sick from coronavirus (34%) or will have to miss work due to a coronavirus infection (36%). About a quarter (27%) say they are worried they will be hospitalized for COVID-19. Each of these worries are more prevalent among adults with lower incomes and people of color. For example, Hispanic adults (57%) and Black adults (43%) are much more likely than White adults (27%) to say they are worried about having to miss work due to a coronavirus infection, as are those with incomes under $40,000 compared to those with higher incomes (46% vs. 31%). Hispanic and Black adults are also more likely than White adults to say they are worried about becoming infected with omicron, becoming seriously ill, or being hospitalized due to coronavirus, as are lower-income adults compared to their higher-income counterparts.

Similar to previous KFF Vaccine Monitor findings, vaccinated adults are also more likely than those who are unvaccinated to say they are worried about getting infected with, getting seriously sick from, or being hospitalized due to coronavirus. At least three in ten vaccinated and unvaccinated adults are worried about having to miss work due to a coronavirus infection.

While many adults, and particularly people of color, are worried about the personal impacts of omicron, the public overall says omicron has made them more worried about the pandemic’s impact on the economy, their local hospitals, and people who are unvaccinated. Majorities say that compared to previous surges of the pandemic, they are now more worried about the impact of omicron on the U.S. economy (56%) and on their local hospitals (54%). Half of adults also say they are more worried about omicron’s impact on people who are not vaccinated, however this largely reflects the vaccinated population’s worry about the unvaccinated. Among unvaccinated adults themselves, just 15% say they are more worried about omicron’s impact, compared to 61% of vaccinated adults who are worried about the impact on the unvaccinated.

When it comes to personal impact, the public reports being less worried about omicron than they were about previous waves of the pandemic. Majorities say that compared to previous surges, they are less worried about the impact of omicron on themselves personally (69%) and on their way of life (58%). An even larger share of unvaccinated adults say they are less worried about the impact of omicron on themselves personally (76% of unvaccinated adults, compared to 67% vaccinated) and their way of life (66% of unvaccinated adults, 55% vaccinated).

About seven in ten adults (71%) say they are “very” or “somewhat” worried that restrictions aimed at stopping the spread of omicron will hurt local businesses in their area and similar shares (68% each) say they are worried that their local hospitals will be overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients or that other new and more serious variants will spread in the United States. While majorities across partisans express worry about the impact of restrictions on local businesses, Democrats are much more likely than Republicans to worry that their local hospitals will be overwhelmed (86% vs. 50%) or that new variants will develop and spread in the U.S. (86% vs. 48%).

Despite widespread reports of vaccinated individuals becoming infected with the omicron variant, most adults (62%) say “the fact that most vaccinated people who become infected with COVID-19 do not require hospitalization means that the vaccines are working” while about a third (34%) say “the fact that some vaccinated people are becoming infected with COVID-19 means that the vaccines are not working.” Notably, the share who see breakthrough infections as a sign that the vaccines are not working has increased slightly since September (from 26% to 34%), mainly driven by an increase among Republicans (from 39% to 50%) and unvaccinated adults (from 66% to 84%).

Omicron’s Impact On Behaviors

When asked about the impact of omicron on their own behaviors, 43% of adults say the spread of the new variant has made them more likely to wear a mask and nearly as many (38%) say it has made them more likely to avoid large gatherings. Reflecting their higher levels of worry about becoming infected with omicron, Black and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to say the new variant has prompted them to change their behavior, as are vaccinated adults compared to unvaccinated adults and Democrats compared to Republicans.

Trend data also reveals that self-reported mask usage has increased among the public since last summer. A majority of adults (57%) now say they wear a mask every time when they are in a grocery store, a 20-percentage point increase since July 2021. About half of the public say they wear masks every time at work (47%) or on public transportation (49%), up from about a third in July. While a majority of adults (54%) say they were a mask every time they are in an indoor crowded place, fewer (33%) report consistent mask usage in crowded outdoor spaces. Overall, Black and Hispanic adults are more likely than White adults to report consistent mask usage, as are vaccinated adults compared to those who are not vaccinated. Across partisans, Democrats are roughly two to three times as likely as Republicans to say they wear a mask every time in each of the situations presented.

Trends In COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions And Uptake

After holding relatively steady for several months, COVID-19 vaccine uptake inched up between November 2021 and January 2022. More than three-quarters of adults (77%) now report that they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, up from 73% in November. One percent say they plan to get vaccinated as soon as possible, 4% say they want to “wait and see” before getting a vaccine, and 3% say they will get vaccinated only if they are required for work, school, or other activities. One in eight adults (14%) say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated for COVID-19, a share that has held generally constant since December 2020.

The spread of omicron in the U.S. does not appear likely to motivate more unvaccinated adults to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Three in four unvaccinated adults (76%) say that news of the omicron variant spreading has not made much of a difference as to whether they will get the vaccine while just 8% said it has made the more likely to get vaccinated and 15% say it has made them less likely to do so.

Looking at demographic patterns of COVID-19 vaccine uptake, we continue to find that Democrats, college graduates, older adults, and those living in urban areas report being vaccinated at higher rates than Republicans, those without college degrees, younger adults, and rural residents.

The age gap in vaccine uptake appears to be shrinking somewhat with 73% of 18-29 year-olds and 72% of 30-49 year-olds now saying they are vaccinated, compared to about two-thirds in November. In addition, the shares of Republicans (63%) and independents (76%) who report being vaccinated reached new highs this month, though still lagging significantly behind the vaccination rate among Democrats (91%). Notably, a quarter of Republicans (26%) continue to say they will “definitely not” get vaccinated, a share that has held relatively steady since December 2020.

Vaccine Booster Uptake And Intentions

A recent study released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found that a booster dose was effective in preventing hospitalization due to COVID-19 and the CDC announced earlier this month that a booster dose will be required for adults to be considered “up-to-date” on their COVID-19 vaccinations. We find that among adults overall, about four in ten (42%) have received a booster dose, while 34% have received at least one vaccine dose but are not boosted and 22% remain unvaccinated.

Mirroring their earlier uptake of the initial vaccine doses, Democrats (62%) are more likely than independents (37%) and Republicans (32%) to have received a booster. Similarly, two-thirds of adults 65 and older and half of adults ages 50-64 have received a booster, compared to three in ten adults ages 30-49 (31%) and a quarter of those ages 18-29 (24%) who say the same.

Notably, across racial and ethnic groups, White adults (46%) are more likely than Black (31%) and Hispanic (37%) adults to say they have received a booster dose of the vaccine, while larger shares of Black and Hispanic adults are vaccinated but not boosted (49% and 39% respectively, compared to 29% of White adults). This may at least partially reflect some Black and Hispanic adults not yet being eligible for a booster if their initial course of vaccination was completed more recently, since access issues and other concerns delayed initial vaccine uptake for some people.

Among vaccinated adults who are likely eligible for a booster dose (those who either got a booster or completed an initial full course of vaccine at least six months ago), seven in ten have gotten a booster. This rises to 86% among those ages 65 and over and 77% among those ages 50-64 who are likely booster-eligible.

However, there is evidence that booster uptake and access may be lagging among the booster-eligible population of Black adults. Among the likely booster-eligible population, 57% of Black adults compared with 69% of Hispanic adults and 72% of White adults have gotten a booster.

The racial and ethnic gap in booster uptake does not appear to be driven by a lack of desire among Black and Hispanic adults to get boosted. Among those who are vaccinated but not yet boosted, four in ten (39%) say they want to get a booster dose as soon as they can, including 41% of Black adults and nearly half of Hispanic adults (47%).

On the other hand, resistance to getting a booster does appear to be a factor in the partisan gap in booster uptake. A majority (58%) of Democrats who are vaccinated but not yet boosted say they want to get a booster dose as soon as they can, compared to just 18% of Republicans who have not yet gotten a booster. Indeed, about half (53%) of vaccinated but not yet boosted Republicans say they will either “definitely not” get a booster (23%) or will only do so if they are required (30%).

Most vaccinated but not boosted adults (60%) say news of the omicron variant spreading has not made much of a difference as to whether they will get a booster. However, about three in ten (29%) say the spread of omicron has made them more likely to get a booster shot, a share that rises to 41% among Hispanics who are vaccinated but not boosted.

When asked to say in their own words the main reason they have not gotten a booster dose, about one in eight vaccinated but not boosted adults offer that they feel that their initial vaccination doses are enough or that they don’t need it (13%) and a similar share say they are currently not eligible for a booster (12%). Other common reasons provided include doubts about the efficacy of boosters, including those who cite the fact that vaccinated people are still getting sick (9%), being too busy or not having time to get a booster (8%), having already gotten COVID-19 (7%), work-related concerns such as having to miss work to get the shot or recover from side effects (5%), medical issues (5%), procrastination (5%) and wanting to wait and see how boosters are working (5%).

Among those who are more open to getting a booster (those who say they want to get a booster dose as soon as possible or wait and see), the most common reasons given for not getting a booster are that they aren’t eligible (17%), are too busy (12%), already had COVID-19 (8%), or haven’t gotten around to it or have been putting it off (8%). Those who are more reluctant (saying they will get a booster only if required or will definitely not get one) cite different reasons for not getting boosted, with the top answers being that they feel they don’t need a booster or feel the initial vaccination is enough (22%), or that they question the boosters’ effectiveness (19%).

Across racial and ethnic groups, one in five Hispanic adults who are vaccinated but not boosted (21%) cite lack of eligibility as the main reason they have not gotten a booster dose, as do 13% of Black adults and 10% of White adults. Notably, about one in ten vaccinated but not boosted Black and Hispanic adults said they have been too busy or haven’t had time to get a booster dose of the vaccine.

In their own words: What is the main reason you have not gotten a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine?

“I feel that my initial doses were enough” – 36 year-old male, White, Texas

“Because I received my second shot and I have to wait 4 more weeks to receive the booster shot.” – 33 year-old male, Black, Maryland

“Not enough time between doses” – 63 year-old male, White, Oregon

“Because I have to wait until 6 months” – 67 year-old male, Hispanic, Arizona

“First, I don't trust the vaccine and I'm seeing a lot of people vaccinated and still getting sick” – 39 year-old female, Hispanic, Nevada

“Because I know a few people that received the booster and still contracted covid” – 36 year-old female, Black, Pennsylvania

“I don’t think it makes any difference if people are getting vaccinated and people are still getting sick senior citizens are dying” – 56 year-old male, White, Tennessee

“No appointments in my area” – 65 year-old male, Black, Maryland

“I haven't had any time off from work” – 31 year-old female, Black, Mississippi

“Missing work from side effects” – 18 year-old male, Hispanic, Missouri

“Tired of the federal government telling me what to do” – 55 year-old female, White, Maryland

The spread of the omicron variant has led some disease experts to call for COVID-19 vaccine mandates for air travel. Overall, most of the public think that COVID-19 vaccination should be required for international air travel (62%) and for domestic air travel (55%) and about half think there should be a vaccination requirement for train travel within the U.S. (51%). Unsurprisingly, there are large partisan differences on whether to institute vaccination requirements for travel. More than three in four Democrats think there should be a vaccine requirement for air travel and train travel, whereas about four in ten Republicans (39%) think a requirement should be in place for international travel, and about one in four think a requirement should be in place for domestic travel by air (28%) or train (25%).

COVID-19 Testing

How Many Adults Have Personally Tested Positive For COVID-19?

Almost a quarter of adults now say they have personally tested positive for COVID-19 at some point (23%), while another 12% say someone in their household has tested positive and 49% say someone else they know has. Around a third of unvaccinated adults say they have tested positive at some point (34%), significantly higher than the share among vaccinated adults (21%).

Notably, while unvaccinated adults are more likely than those who are vaccinated to say they tested positive for COVID-19 at some point, similar shares of vaccinated and unvaccinated adults say they tested positive within the past month amid the omicron surge (7% and 10%, respectively).

Amid concerns that official COVID-19 case counts may be an underestimate if many people are taking at-home tests that are not recorded by government agencies, about eight in ten of those who say they tested positive in the past month say they received a positive result on an in-person test (66%) or on both an in-person and at-home test (17%).

One in six (16%) adults who received a positive test result in the past month (representing about 1% of all U.S. adults) say that result came on an at-home test only. With few states or localities offering residents a way to report their at-home tests, these results are unlikely to be included in official case counts.

Experiences With Testing Access

With COVID-19 cases surging to unprecedented levels over the past two months, many U.S. adults report difficulty accessing both at-home and in-person COVID-19 tests.

While many made an effort to find testing for COVID-19, some – depending on what type of test they sought – struggled with the task. A majority (65%) of adults who tried to get an in-person COVID-19 test in the past month say it was easy, though a substantial share, 35%, say it was difficult. At-home tests presented even more of a challenge, with 62% of those who tried to find an at-home test reporting it was difficult and 38% saying it was easy.

Overall, 23% of all adults say that they tried to get either an in-person or at-home test in the past month and had difficulty finding one, 24% tried and didn’t have any difficulty, and 52% didn’t try to access either type of test. Suburban (27%) and urban (24%) residents are more likely than rural residents (12%) to report difficulties finding tests in the past month. As well, higher shares of young adults (33% of those ages 18-29) and adults with high incomes (32% of those with a household income of $90K or more a year) reported difficulties finding tests. These differences are largely a reflection of the higher shares of these groups who said they attempted to purchase at-home tests, which were often in short supply.

The vast majority (89%) of those who attempted to get an in-person COVID-19 test in the past month say they were able to get one, including 58% who say they got a test on the first day they wanted one. However, 11% of those who tried to get such a test (4% of all adults) say they were unable to get an in-person test, and 23% (7% of all adults) say they had to wait 2 days or more to be tested. Combined with the longer wait time for the results of in-person tests, this could result in delays in returning to work or other activities for people who were exposed or experiencing symptoms of COVID-19.

Among those who tried to get an at-home test, one-third (33%, or 9% of all adults) say they were unable to get one, mainly because tests were not available rather than being too expensive (91% vs. 2% among those who tried but could not get an at-home test).

Perceptions Of Test Access In Local Areas

Beyond their personal experiences, about half of adults (48%) feel that there are not enough COVID-19 tests available in their local area for people who want them, while 45% believe there are enough tests. Residents of rural areas are more likely to think there are enough tests in their area (53%) compared to suburban residents (42%). President Biden announced on January 14th that Americans could order at-free home tests beginning on January 19th, while the survey was still in the field.

Adults with higher incomes and those in urban and suburban areas are more likely to feel that the testing supply isn’t adequate, which may reflect the fact that they were more likely to say they have sought out at-home tests, which many people reported difficulty finding.

Despite reported difficulty accessing tests, most adults are confident they would be able to access COVID-19 testing if needed. About eight in ten adults overall say they are confident that they would have access to COVID-19 testing if they were exposed to the virus (81%), with about half saying they are very confident (51%).

Who Does The Public Blame For Issues With Testing?

When asked who is responsible for the limited availability of COVID-19 tests in the U.S., around half of adults (49%) say that the FDA deserves a lot or a fair amount of blame for the limited availability of COVID-19 tests in the United States. Slightly fewer think President Joe Biden deserves a fair amount or a lot of blame (44%) with a similar number who say the same about the COVID-19 test manufacturers (41%). However, more adults say that Biden deserves a lot of blame (26%), compared to the FDA (19%) and test manufacturers (16%).

Republicans and unvaccinated adults are more likely than Democrats and vaccinated adults to place at least a fair amount of blame for test shortages on President Biden and on the FDA. Three in four Republicans (75%) and more than four in ten independents (44%) say President Biden deserves a lot or a fair amount of blame for the limited availability of COVID-19 tests, compared to one in five Democrats (21%) who say the same. Similarly, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say the FDA deserves a lot or a fair amount of blame (62% vs. 39%).

Confidence In Accuracy Of Testing

In addition to difficulty accessing at-home tests, many adults lack confidence in their accuracy. While a large majority are very (43%) or somewhat (39%) confident that the results of in-person COVID-19 tests at a medical facility or testing site are usually accurate, far fewer are very (11%) or somewhat (44%) confident in the accuracy of at-home tests.

Views Of CDC Guidance Following Testing Or Exposure

Even after testing positive or being exposed to COVID-19, many still are not sure what they are supposed to do. Around one in five adults (19%) report they have personally had difficulty in the past three months figuring out whether they needed to isolate or limit their normal activities due to a COVID-19 exposure, positive test, or symptoms they were experiencing. Adults under 65 (22%) are more likely than those 65 and older (8%) to say they have had difficulty figuring out whether they needed to isolate or limit their normal activities; among 18-29 year-olds more than one in four (27%) report difficulty making personal decisions around COVID. Notably, 38% of those who say they tested positive for COVID-19 in the last month say they had difficulty deciding whether they needed to isolate, as did 37% of those who reported difficulty finding a COVID-19 test.

In late December, the CDC shortened the recommended isolation time for people who test positive for COVID-19 from 10 days to 5 days, followed by another five days of wearing a mask. Some individuals and organizations, including the American Medical Association, questioned the wisdom of the updated guidelines and whether they would be confusing for people to follow. In addition, some states and localities, including Washington, DC, have continued to advise residents to observe a 10-day isolation period. Our findings suggest that the change has indeed been confusing for the public, with around six in ten adults (58%) saying the CDC guidelines for testing and isolation for those exposed or infected with COVID-19 are confusing, while 39% think the guidelines are clear.