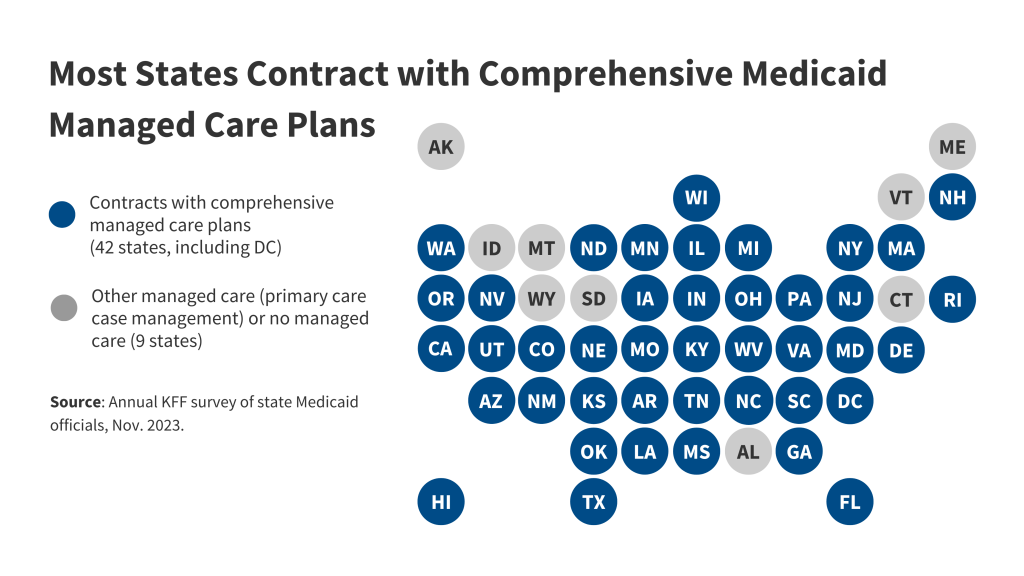

As concerns continue to be raised about consumer barriers to care resulting from prior authorization requirements, the federal government issued a final regulation aimed at streamlining and automating the prior authorization process and improving transparency for certain payers. Over the past two years, research and investigations into the use of prior authorization in Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care plans have brought renewed attention to the prior authorization process. For private commercial coverage, a growing number of states have passed wide-ranging prior authorization changes. This Issue Brief discusses the final regulation issued by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), how it might address some of the current consumer concerns, and the areas that are left for further evaluation. Key takeaways include:

- The new regulation will apply largely uniform prior authorization standards across almost all insurance programs that CMS oversees: Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces run by the federal government, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) fee-for-service and managed care plans, and Medicare Advantage plans. These rules do not apply to prescription drug prior authorization, or prior authorization processes for most employer-sponsored health plans.

- The use of electronic processes to share the data needed for prior authorization review promises to improve the speed and efficiency of the process, but hurdles could exist that limit actual use of these technologies including patient awareness, limited education about how to use these features, and data privacy and security concerns.

- New transparency requirements will provide information to enrollees and the public about the specific services that require prior authorization by their health plan, and aggregate information about prior authorization claim denials. Claim denial information about the specific types of services denied is not included.

- The regulation will require some plans to shorten time frames for making prior authorization decisions but does not address how plans figure out what services require prior authorization; the clinical coverage criteria plans decide use to make prior authorization decisions; or the appeals structures in place that allow consumers to appeal a prior authorization denial to the plan and independent appeal entities.

Final Rules Focus on Electronic Processes and Increased Transparency

The major aim of the final rule is to improve the speed and efficiency of making prior authorization decisions through the standardized electronic exchange of information. It applies to payers (insurers and in the case of Medicaid fee-for-service, states) for the following plans: Medicare Advantage plans, Medicaid and CHIP fee-for-service and managed care plans, and qualified health plans (QHPs) on the federal Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplace. These payers will be required to make prior authorization information available through four different application programming interfaces (APIs). This will allow providers, payers, and consumers to know what medical items and services require prior authorization, what documentation is required for the plan to make a prior authorization decision, and the current status of a prior authorization decision (Box 1). The rule does not apply to most employer-sponsored health plans.

Box 1: Prior authorization details available through the APIs include:

- Prior authorization status

- Date of approval or denial of a prior authorization request

- Date or circumstance when the prior authorization ends

- What items or medical services were approved

- Reason for denial, if denied

- Administrative and clinical information submitted by a provider

Four APIs are included in the final rule (Table 1). The Patient Access, Provider Access, and Payer-to-Payer APIs facilitate exchange of claims and clinical information about a patient so that it is more easily accessible electronically to make prior authorization decisions. This could also include information about past prior authorization decisions useful for a patient that is required to obtain prior authorization again for the same service when switching health plans. The Prior Authorization API will be used in the prior authorization process to pass information between the provider and payer.

Effective Date: The effective date of these new functionalities was changed from the January 2026 effective date in the proposed regulation to January 2027, giving payers extra time to implement what may be new processes for some of these plans. While nothing prevents these plans from putting these standards in place before then, the delay means that providers and consumers might not see noticeable changes soon.

Limits of API standards. The final rules will likely result in improvements where the API processes are utilized by providers and patients. Notably, these rules put requirements on payers to make certain information available so it can be accessed through an API. However, it will still require providers and patients to voluntarily use these API processes to take advantage of these efficiencies. Third party applications—consumer applications for the Patient Access API and electronic health record software for the Provider Access API—will likely need to be available to make this happen.

Patient use. CMS indicates in the final rule that consumers have been slow in utilizing the existing Patient Access API functionalities and may require additional education and resources to take advantage of the Patient Access API. CMS will be tracking consumer use of the Patient Access API through annual reporting requirements including the total number of unique enrollees whose data are transferred using the Patient Access API. While this number might help gauge traction of the API overall, it may not accurately reflect patient engagement in the prior authorization process. This API may be used for purposes other than monitoring prior authorization, such as downloading a clinical history. Additionally, consumer interaction with the insurer where the API is not used, either through insurance portals or telephone, would not be considered in the metrics even if conveying information on prior authorization.

Providers will be able to access their patient’s information through the Provider API. Patients that do not want their information accessed in this way can opt out to prevent this exchange. Payers must provide educational resources written in plain language to patients describing the Provider Access API and instructions for opting out (or back in) to the data exchange. Since multiple mechanisms exist apart from the new APIs for disseminating patient clinical information (such as through a health information exchange), it may be confusing for some consumers that opting out of the Provider Access API may not prevent their information from being shared.

For the Payer-to-Payer API, a patient’s information will not be shared between payers unless a patient opts in with both their previous and new insurers for data to be exchanged. One potential value of this API is to allow a patient’s new health plan to access information about a prior authorization approval from the patient’s previous health insurer. This might eliminate the time a patient and their doctor must spend to obtain a new prior authorization for the same treatment when a patient must change their health insurance. Given the opt in requirement, lack of awareness of this API could limit its use.

Provider use. Use of the API for providers is voluntary and might not be up to individual practitioners todecide, as increasing numbers of providers are employed by large health systems that make these business decisions. Use of the Provider Access API is broadly available to all in-network providers that treat a given patient, such as specialists who have recently received a referral but have not yet seen the patient. Unless querying the payer through the Provider Access API is enabled by information technology infrastructure and is part of the established provider workflow, use of the API could be somewhat limited. Also, since support of APIs is not universally required of all payers, a provider would need to determine whether their patient has a payer required to provide this information through the API. The final rules do add a new Electronic Prior Authorization measure for providers under the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) to encourage providers to use the Prior Authorization API.

Other Changes Required in the Final Rule

The remaining standards in the final prior authorization regulation would make changes to what CMS calls “business process” rules. Payers will need to make these changes by January 2026 whether API processes are used or not:

Shortened Timeframes. Medicare Advantage plans and Medicaid and CHIP (both fee-for-service and managed care plans) will have to make standard prior authorization decisions within 7 calendar days and expedited decisions within 72 hours of prior authorization requests for medical treatment. Shorter timeframes could apply to programs that are subject to state law, but the rules provide a federal floor of protections. This would tighten some decision-making standards. For example, currently Medicare Advantage timeframes are 14 calendar days for standard decisions. The final regulations do not change timeframes for QHPs on the federal Marketplace (generally, 15 days to make standard prior authorization decisions and 72 hours for expedited requests, although states may have shorter timeframes). See Table 2 for current and new timeframes.

Reasons for denial. Plans must give a specific reason for a denial to the provider and the patient through their APIs. This does not change existing notice rules that may already require notice to patients (and in some case providers). This requirement is meant to align all program standards to make sure providers have the information about a denial so that they can take whatever necessary steps are needed for their patient—whether that is an appeal of the decision and/or a recommendation for an alternative treatment.

New public reporting on prior authorization. All payers covered by the final rule will have to report information about prior authorization determinations. See call out box. The goal is that new transparency of aggregate information about prior authorization will “allow for objective evaluation of the efficiency of prior authorization practices of each organization.” Public reporting information for prior authorization will be available directly for consumers to review on a payer’s website but will not be aggregated by CMS. While there is an expectation that patients could use the information when selecting among plan or organization options, it is not clear whether consumers understand that prior authorization data will be available, how to access them, and how these data could inform their decisions of selecting an insurer. At a minimum, the information posted on the website could be a resource for better information about what items and services require prior authorization.

Box 2. Public Reporting for Prior Authorization (applies to items and services other than prescription drugs)

- List of all items and services that require prior authorization

- Percentage of standard and expedited prior authorization requests approved & denied (aggregated for all items and services)

- Percentage of standard prior authorization requests that were approved after appeal

- Percentage of standard and expedited claims where decision timeframes were extended and then followed by a request approval

- Average and median timeframes between a prior authorization request and decision for standard and expedited prior authorization requests

Issues Remain

The final regulation is a first step toward addressing existing challenges, including those that unnecessarily delay prior authorization decisions, causing patients and providers to scramble to obtain medically necessary care they thought was covered by insurance. This regulation, however, does not get to many of the patients affected by prior authorization and many of the issues raised about prior authorization. This includes the following:

Prescription drugs

Only medical items and services are covered by the final regulation, not prior authorization requirements for drugs, whether self-administered, administered by a provider, dispensed by a pharmacy, or purchased over the counter. CMS cited operational complexities in applying API and other standards, but the agency received many comments objecting to the exclusion of drugs and in response says they will consider options for future rulemaking. Examples of concerns often arising for prescription drug prior authorization include:

- Step therapy. While not limited to pharmacological treatments, step therapy is often a limitation to immediate access to a medication that a provider recommends. Step therapy is where a plan requires a patient to take another medication or treatment and determine it is not effective before it will authorize coverage for a specific medication. Some states require commercial plans with step therapy requirements to have an exceptions process for enrollees whose condition warrants receiving the prescribed and covered medication without trying an alternative beforehand. These state laws do not apply to self-insured employer-sponsored plans, which represent a majority of those covered through employers.

- Claim review timing. Time is often of the essence for medications such as chemotherapy oral medications to treat cancer. CMS points out in the new regulation that some existing programs already have expedited timeframes for review of an initial claim specific to prescription drugs. For example, Medicare Advantage plans must respond within 24 hours to an expedited prior authorization request for a Medicare Part B drug. Medicaid contracting rules require a response within 24 hours of a prior authorization request of a covered outpatient drug if the state requires prior authorization. These expedited timeframes might not apply to commercial insurance provided on the Marketplace unless state law requires it. Federal claims review standards that are part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) were taken from existing ERISA internal claims standards and timeframes issued in a U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) claims and appeals regulation from 2000. These rules do not include timeframes specific to prescription drugs.

CMS does not regulate large private employer plans that are subject to ERISA requirements administered by the DOL. As a result, these rules do not change any of the current requirements for most Americans who are covered by large insured and self-insured employer plans. Even most small employer plans are not covered, unless they obtain their insurance through the Small Business Health Options Program (SHOP) with an insurer that offers coverage to both individuals and small employers on a federal Marketplace. For these private employer plans not covered by the CMS prior authorization rules, federal standards for “internal” claim review and appeal (where a health plan makes an initial coverage decision and then reviews the decision again if a consumer appeals) for prior authorization and other claim decisions have not been updated since 2000. The ACA applied these rules from 2000 to most non-grandfathered individual and group health plans (including Marketplace plans) in 2010.

Prior authorization requirements have been a focus of DOL oversight for mental health parity standards. A 2023 DOL enforcement report noted that these were the top issues where the agency found violations. Also, concerns about the failure to provide adequate notice of the reasons for a denial was the subject of a recent federal appeals court decision that has garnered some attention.

In addition, continuing an already approved prior authorization for those changing employer-sponsored plan benefit options from year to year or transitioning to Marketplace or Medicaid coverage can put a halt to the preauthorized care at the beginning of the plan year (or due to a midyear formulary change). ERISA does not address these types of transitions. Last year, CMS adopted changes for Medicare Advantage coordinated care plans that require a minimum 90-day transition period when an enrollee currently undergoing a course of treatment is new to Medicare or switches Medicare Advantage plans. Plans cannot require reauthorization of care during this 90-day period.

Plan processes for prior authorization decision making

The final regulation does not address how prior authorizations decisions are made within a health plan, including any plan processes for deciding what types of services warrant prior authorization, the clinical and other coverage criteria a plan uses to make these decisions, the individuals and technologies utilized to make prior authorization decisions, and how these prior authorization processes are updated over time as research results in more information about the effectiveness and cost of a service.

Rationale for applying prior authorization. Some point to the wide variation across different health plans of the services that require prior authorization. Scrutiny of this plan variation might uncover unnecessary or outdated use of prior authorization resulting in a high volume of prior authorization requests and the resulting administrative burden on providers and patients. One study of over 200 Medicaid managed care plans that covered buprenorphine (a medication used to treat opioid use disorder) found large variation within and across states on whether plans required prior authorization for the drug.

Clinical coverage criteria. Attention has also focused on the clinical criteria that plans use to make prior authorization decisions. Issues include whether the criteria are transparent to patients and providers, appropriate for the specific claim being evaluated, or whether the criteria are evidence-based. A report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General (OIG) on improper use of a Medicare Advantage plan’s internally-developed clinical criteria for prior authorization decisions led to a 2023 CMS regulation and recent guidance clarifying when such criteria can be used. These rules are limited to Medicare Advantage plans. How clinical coverage criteria are applied has been the subject of litigation involving employer-sponsored plans covered under ERISA, including an ongoing case on the alleged improper use of a plan’s own coverage criteria and a recent case questioning the use of an independently developed clinical guideline.

Use of automated processes. How plans process the millions of prior authorization requests and other claims filed every year has also become the subject of scrutiny. A DOL case filed last summer accused a large third-party administrator of automatically denying certain types of claims without human review, in violation of ERISA rules. In addition, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in claims review has triggered additional private litigation involving Medicare Advantage plans and private plans. It is unclear whether streamlining data collection through the API will facilitate application of such technologies to the prior authorization process and whether similar litigation will result.

Appeals of prior authorization decisions

KFF research indicates that few patients engage the appeals process, whether for prior authorization in Medicare Advantage plans or for claims from federal Marketplace plans denied for lacking prior authorization. A denial of prior authorization is a “claim denial.” Many are not aware they have a right to appeal, according to the KFF 2023 Consumer Survey. Some consumers may not have the time or ability to navigate a complicated appeals process. Others may be relying on their provider to take action. A KFF analysis of Medicare Advantage prior authorization denials found that of the small number of denials that were appealed to the health plan (an internal appeal), a large percentage (82%) were either partially or completely overturned. Increased use of appeals processes might uncover improper prior authorization claim denials, whether resulting from an administrative mistake or more systemic problems in a claims review system.

Limited appeal information in final rule. The CMS final prior authorization rule will provide some new and ongoing information about prior authorization, but limited information about appeals of prior authorization denials. Plans must publicly report the percentage of prior authorization requests that were approved after appeal but does not require that plans provide any other information about the specific service involved in the appeal, the reason for the initial denial, or the rate of appeal to health plans. While some information is reported to CMS or states for Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, currently there are few sources for information about appeals in private coverage available. The Market Conduct Annual Statement (MCAS), developed by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), can provide most states with uniform market-related commercial health plan information and data including on prior authorization requests, approvals, denials, and external appeals requests for adverse benefits determinations which are reported in aggregate and not publicly available. CMS also releases data on claims denials and appeals for QHPs offered on the federal Marketplace, including for prior authorization.

No information on the use of independent and automated systems of appeal. The CMS final regulations appear to require plans to report on their own appeals outcomes—those appeals reviewed by plans internally—but not the outcome of independent external review of prior authorization denials. All appeals systems have some form of independent external appeal entity. For private coverage, including Marketplace and employer-sponsored coverage, the ACA added the option for independent appeals for certain claims. Patients must individually request to appeal a denied prior authorization claim to external appeal. By contrast, Medicare Advantage plans require automatic review of a claim denial by an external entity (an Independent Review Entity or IRE) following the denial of a claim on appeal to the health plan. For consumers in Medicaid managed care plans, state fair hearing and access to independent appeal entities is available, but an HHS OIG report found these enrollees in Medicaid managed care plans are less likely to have access to an external, automated review process compared to Medicare enrollees.

Looking Forward

Prior authorization will continue to be an important tool for health insurers. Many insurers have announced that they have reduced the volume of prior authorization requirements, but with few specifics on where these reductions are being made. Congress is starting to focus on prior authorization reforms, with pending legislation that would make changes for Medicare Advantage plans (for example, H.R. 4822) and an investigation by at least one Congressional committee on prior authorization practices of Medicaid managed care plans. A recent Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D final regulation will require plan utilization management committees to issue an annual plan level health equity analysis of prior authorization policies.

Even for electronic processes, there is more to come. Further actions will likely involve including API functionality in the provider’s electronic health record to make it easier to use these automated electronic processes. More streamlined processes might also focus not just on business processes, but on how patients use the system, allowing them to appeal a prior authorization or claim denial to an independent entity through a simple process on their smart phones so that they can also get the benefit of innovation. Enhanced visibility into the prior authorization process by patients, through means enabled by the patient access API, could increase patient engagement in the process and contribute to a higher appeal rate.

As the number of health apps using the patient access API grows, there is increasing opportunity for monetization of patient information, with potential security and privacy risk to the payers’ systems. While payers must provide information to their subscribers on steps to protect their privacy, this limited education might not be sufficient to prevent users from authorizing the collection of commercially valuable patient information by app developers, who may not be covered entities under HIPAA privacy rules. Inclusion of prior authorization information could make mining for certain conditions easier. Questions surrounding security also exist in addition to privacy concerns. The recent cybersecurity breach at UnitedHealthcare is a reminder of the limits of the sole reliance on electronic systems. There may be renewed attention to the importance of enhanced security and privacy protections as systems of data exchange become more interoperable.