.

Appendix A: State Comparison Chart

| | Alabama | California | Connecticut | Illinois49 | Missouri | Virginia |

| Medicaid Family Planning Program |

| Name | Plan First | Family PACT | N/A | N/A | N/A | Plan First |

| Waiver or SPA | Waiver(Established in 2000) | SPA(Converted from waiver in 2011) | SPA(Established in 2012) | N/A(Waiver terminated in 2014) | Waiver(Established in 1998) | SPA(Converted from waiver in 2011) |

| Gender/Age Eligibility | Women, 19-55 Men, 21 and older (only for vasectomies) | Women, no age restrictions Men, no age restrictions | Women, no age restrictions Men, no age restrictions | N/A | Women, 18-55 | Women, no age restrictions Men, no age restrictions |

| Income Eligibility | 141% FPL | 200% FPL | 263% FPL | N/A | 201% FPL | 200% FPL |

| FP-Related Benefits? | No50 | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | No |

| Family Planning Program Enrollment(Source: state interviews) | 103,288(as of 12/31/15) | 1,000,000(2016 estimate) | 274(2016 estimate) | N/A | 71,000(2016 estimate) | 110,000(2016 estimate) |

| Coverage Landscape |

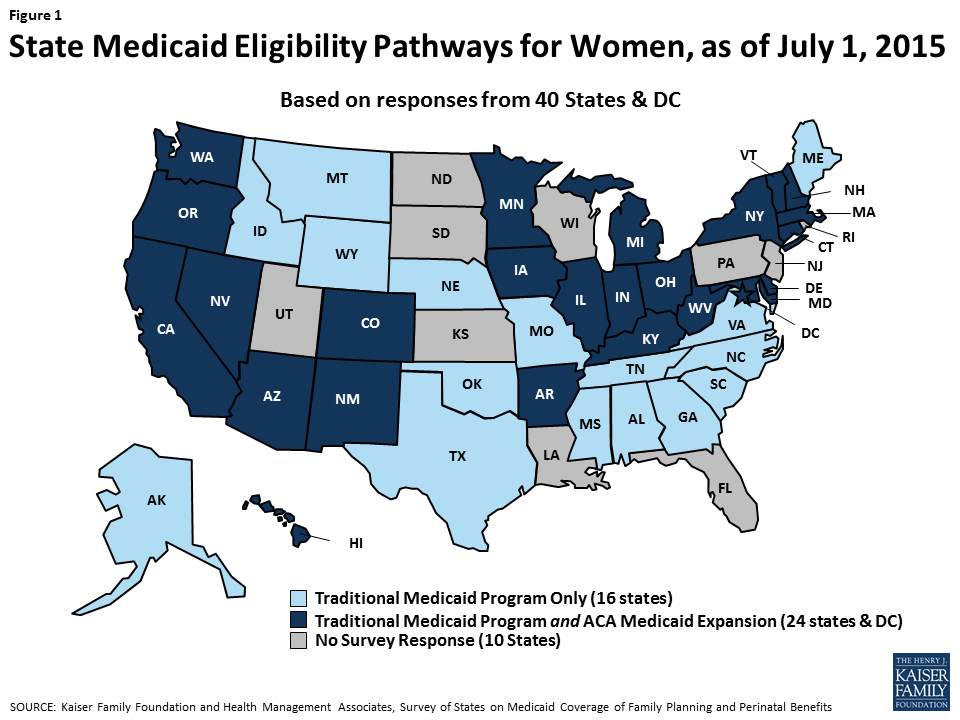

| Expanded Medicaid? | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| % of Medicaid Enrollees in Managed Care51 | 0% | 77% | 0% | 53% | 51% | 66% |

| Rely on Healthcare.gov? | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Demographics |

| Distribution of adults ages 19-64 enrolled in Medicaid, by sex, 2014(Source: U.S. Census Bureau) | Female: 60%Male: 40% | Female: 55%Male: 45% | Female: 58%Male: 42% | Female: 53%Male: 47% | Female: 56%Male: 44% | Female: 59%Male: 41% |

| Distribution of women ages 19-64, by FPL, 2014(Source: U.S. Census Bureau) | Below 100% FPL: 18%Below 400% FPL: 67% | Below 100% FPL: 16%Below 400% FPL: 62% | Below 100% FPL: 9%Below 400% FPL: 46% | Below 100% FPL: 14%Below 400% FPL: 58% | Below 100% FPL: 11%Below 400% FPL: 59% | Below 100% FPL: 12%Below 400% FPL: 52% |

| Health insurance coverage of women ages 19-64, 2014(Source: KFF Women’s Health Insurance Coverage) | ESI: 57%Direct purchase: 8%Medicaid: 13%Other: 9%Uninsured: 14% | ESI: 53%Direct purchase: 9%Medicaid: 22%Other: 4%Uninsured: 13% | ESI: 67%Direct purchase: 8%Medicaid: 14%Other: 3%Uninsured: 8% | ESI: 63%Direct purchase: 7%Medicaid: 16%Other: 3%Uninsured: 11% | ESI: 64%Direct purchase: 7%Medicaid: 11%Other: 5%Uninsured: 13% | ESI: 63%Direct purchase: 9%Medicaid: 7%Other: 9%Uninsured: 13% |

Back to top

Appendix B: State Profiles

Alabama State Profile

Family Planning Overview: Alabama operates Plan First, a waiver program that covers family planning services for women ages 19-55 with incomes up to 141% FPL. The program also covers vasectomies for men age 21 and older with incomes up to 141% FPL. Alabama’s Plan First program does not cover other medical services. The Alabama Medicaid Agency manages eligibility and enrollment for the program. The Alabama Medicaid Agency collaborates with the Department of Public Health (DPH) to administer a unique case management program for Plan First enrollees. The DPH operates 84 health centers where many enrollees seek care.

Alabama Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Levels as % of FPL52 Eligibility levels do not include 5% income disregard

| Children by Age (Medicaid) | Separate CHIP | Pregnant Women(Medicaid) | Parents | Childless Adults |

| 0-1 | 1-5 | 6-18 |

| 141% | 141% | 141% | 312% | 141% | 13% | N/A |

Share of Medicaid Population Covered by Different Delivery Systems53

| % of Medicaid Population Covered |

| Fee-for-Service (FFS) | 36% |

| Primary Care Case Management (PCCM) | 64% |

Brief Program History: Alabama established Plan First in October 2000 through an 1115 waiver. At that time, the program provided family planning services for women ages 19-44 with incomes up to 133% FPL not otherwise eligible for Medicaid or Medicare or for those who were losing Medicaid pregnancy coverage after 60 days postpartum. Plan First was expanded in 2008 to include women ages 19-55. In the most recent waiver amendment, the eligibility level was adjusted to 141% FPL54 due to ACA rules for basing eligibility on the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) formula and men were added as eligible individuals for vasectomies only. The State elected not to pursue a state plan amendment (SPA) due to the administrative burden of converting from a waiver to a SPA. As of December 2015, 103,288 individuals were enrolled in Plan First.

Program Enrollment & Access to Care: Individuals who apply for Medicaid with the State Medicaid agency must affirmatively opt-in to have their eligibility determined for the Plan First program. An applicant would check a box on the Medicaid application to indicate interest in Plan First in order to have his/her eligibility determined for the program. Alabama developed this approach in 2010 after finding that enrollees who had been auto-enrolled were not utilizing or interested in family planning services. Individuals who apply at HealthCare.gov do not have their eligibility determined for Plan First.

Plan First enrollees have access to a network of nearly 1,7000 providers, including public health clinics, FQHCs, and private providers.55 Notably, there is at least one public health site that offers family planning services in all but one county. These sites serve as key access points since much of Alabama is designated as a medical shortage area for primary care by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration.56

Intersection with Full-Scope Medicaid: Alabama enrolls “full-scope” beneficiaries into either fee-for-service or primary care case management plans. Full-scope enrollees have access to family planning and family planning-related services, whereas Plan First enrollees are covered only for family planning services.

LARC: Alabama promotes LARC utilization through provider education using the program’s website, ALERTS, care coordination in the Maternity Care program, in public health clinics and through the use of ADPH case management system. Notably, information about different types of contraceptive coverage and educational materials for both Plan First recipients and providers are available on the website and through outreach education provided through a partnership agreement with DPH. DPH provides family planning outreach services to Medicaid eligibles and potential Medicaid eligibles to include orientation pamphlets, posters, and flyers, designed to increase awareness of the availability of benefits of family planning methods.

Nurse practitioners providing services in a public health clinic use a tiered contraceptive chart to counsel patients on the effectiveness of different contraceptives, including LARCs. State law bars a nurse practitioner from inserting an IUD without a physician on staff, so women electing IUDs at a public health clinic are referred out to a physician. Nurse practitioners are permitted to remove IUDs without physician oversight.

In April 2014, Alabama started reimbursing hospitals for LARCs inserted immediately post-delivery. Specifically, the State covers the hospitals’ cost of the LARC device or implant and insertion is billable to Medicaid when the insertion occurs either immediately after delivery and before discharge from an inpatient setting, or in an outpatient setting after delivery and immediately after discharge from an inpatient setting.57

According to Alabama’s most recent waiver evaluation, LARC utilization among Plan First enrollees increased slightly from 2009 to 2014, from 29% to 32%.58

Other Initiatives: Alabama provides case management for individuals at high risk for unintended pregnancy and has made a concerted effort to ease Plan First enrollment and renewal processes.

- Case management has been a key component of the waiver since its inception in 2000. DPH employs social workers who cover all of Alabama’s 67 counties to conduct risk assessments to determine if Medicaid recipients enrolling for family planning services are at high risk for unintended pregnancies. When an individual is identified as high risk, social workers complete a psychosocial assessment and follow-up with individuals regarding family planning appointments and birth control.

- Case managers play an important role in linking women that seek care under the Plan First program and elect an IUD insertion with a provider that can insert an IUD.

- In 2012, Alabama started offering express lane eligibility and utilizing data from the Department of Human Services to process automatic renewals for the Plan First program.

Delivery System Reform: Alabama plans to transition its Medicaid program to managed care delivered through hospital and provider led entities called Regional Care Organizations (RCOs), an initiative that received CMS approval in 2016. RCOs will offer the same services currently provided to FFS and PCCM beneficiaries. The State plans to evaluate family planning outcome measures including utilization of LARC and other forms of birth control. Plan First enrollees will continue to enroll in Medicaid FFS, not through RCOs. Back to top

California State Profile

Family Planning Overview: California administers its “Family PACT” program though a State Plan Amendment (SPA) for women and men “of childbearing age” (there are no official age limitations) with incomes up to 200% of the FPL who have no other source of family planning coverage. Enrollees in Family PACT are covered for family planning services and limited family planning-related services. The Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) manages Family PACT as well as California’s Medicaid program, Medi-Cal while the Office of Family Planning (OFP), which sits within DHCS, provides administrative oversight for the Family PACT program and family planning policies for the DHCS at large.

California Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Levels as % of FPL59 Eligibility levels do not include 5% income disregard

| Children by Age (Medicaid) | Separate CHIP | Pregnant Women(Medicaid) | Parents | Childless Adults |

| 0-1 | 1-5 | 6-18 |

| 261% | 261% | 261% | 317% | 208% | 109% | 133% |

Share of Medicaid Population Covered by Different Delivery Systems60

| % of Medicaid Population Covered |

| Fee-for-Service | 23% |

| Managed Care Organizations | 77% |

Brief Program History: Family PACT was established by the legislature in 1997 as a state-funded program. In 1999, California received approval through a waiver for the program and began receiving matching federal funds. California converted the waiver to a SPA in 2011, retroactive to July 2010, eliminating the need to negotiate and renew the waiver at regular intervals. The state uses an option included in the ACA to extend eligibility under the SPA to individuals who, had they applied on or before January 1, 2007, would have been eligible under the standards and processes in place at that time. One exception is that because California now determines eligibility using the Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) methodology, applicants (with the exception of those aged 17 or younger) must report household income rather than individual income. Family PACT enrollment has been declining in recent years, with 1.3 million enrolled in June 2015, down from to 1.7 million in June 2013.61 Enrollment is expected to continue to decline as more individuals gain comprehensive coverage through Medi-Cal or Marketplace plans.

Program Enrollment & Access to Care: Individuals apply for and enroll in Family PACT directly through their providers by filling out a two-page application in which they attest to residency, household income and lack of other health insurance. Providers assess eligibility based on attested information. They can issue eligible individuals a Family PACT enrollment card on-site at the time of application, allowing them to provide needed services on the same day the individual applies for coverage. During the Family PACT enrollment process, providers are also encouraged to assist individuals who may be eligible for full Medi-Cal coverage in completing their application or advise them on where they can obtain further application assistance.

Family PACT enrollees can access family planning services through 2,200 providers, including a range of both public and private providers.62

Intersection with Medicaid Managed Care: Since California expanded Medicaid under the ACA, some Family PACT enrollees with incomes less than 138% FPL have become eligible for full-scope Medi-Cal. While the State has not tracked the number of individuals that have transitioned from Family PACT to full-scope Medi-Cal, the vast majority of enrollees have likely moved into Medi-Cal managed care plans (approximately three-quarters of all full-scope enrollees are enrolled in managed care plans). At the time of Medicaid expansion, there were some minor differences between the benefit packages for full-scope Medi-Cal versus Family PACT. Since then, however, the State has made a concerted effort to align the benefit package for the two programs, primarily by adding some new services to full-scope Medi-Cal.

LARC: While the proportion of Family PACT clients utilizing LARC methods has increased over the past ten years, California continues to work to further educate and train providers on LARC methods. For example, the State has conducted webinars for Family PACT and Medi-Cal providers to dispel common myths about LARC placement and to encourage providers to offer women the option of same-day LARC insertion. The State also continues to examine challenges that providers may face related to obtaining LARC devices and reimbursement for LARC procedures.

Other Initiatives: California has undertaken efforts to develop family planning quality measures and transition eligible individuals into comprehensive coverage, including:

- DHCS will continue to implement quality improvement and utilization management improvements within Family PACT, which would further enable the State to evaluate the quality and cost-effectiveness of services provided through the program. These evaluation efforts will replace a long-standing contract the state previously held with UCSF to evaluate Family PACT.

- California was a recipient of $400,000 from CMS’s Contraceptive Use Measure Grant,63 which it is using to develop LARC quality measures aimed at improving access to LARC.

- Medi-Cal distributed grants to providers, including Family PACT providers, to conduct enrollment outreach to their patients who may be eligible for comprehensive coverage through Medi-Cal.

Delivery System Reform: California’s first “Bridge to Reform” 1115 waiver, which included a Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, expired after five years on October 31, 2015. After months of negotiations to renew the waiver, CMS agreed to extend “Bridge to Reform” until the end of 2015 and then granted approval for the renewal waiver, Medi-Cal 2020, which took effect on January 1, 2016 and operates through December 31, 2020. Medi-Cal 2020 includes a number of different initiatives aimed at broader delivery system reform and preparing public hospitals for alternative payment methodologies, but family planning is not a focus of any of them. Back to top

Connecticut State Profile

Family Planning Overview: Connecticut administers its family planning program through a SPA for men and women of child-bearing age (including minors) who are not otherwise eligible for full-scope Medicaid, with incomes up to 263% FPL. Enrollees in the program are covered for both family planning and family planning-related services. The program is administered by the Department of Social Services (DSS).

Connecticut Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Levels as % of FPL64 Eligibility levels do not include 5% income disregard

| Children by Age (Medicaid) | Separate CHIP | Pregnant Women (Medicaid) | Parents | Childless Adults |

| 0-1 | 1-5 | 6-18 |

| 196% | 196% | 196% | 318% | 258% | 150% | 133% |

Share of Medicaid Population Covered by Different Delivery Systems65

| | % of Medicaid Population Covered |

| Fee-for-Service | 100% |

| Managed Care Organizations | 0% |

Brief Program History: Connecticut’s family planning SPA went into effect on March 1, 2012. While there was interest in establishing a family planning waiver prior to the implementation of the SPA, a program was never established. When the ACA made the SPA option available, the State leveraged the simpler implementation process.

Program Enrollment:Using presumptive eligibility, providers trained by DSS deemed as qualified entities submit a condensed online application via the DSS “ConneCT” system for those who appear eligible for the family planning program. To obtain coverage beyond the presumptive eligibility period—which lasts through the conclusion of the month following the month of application–individuals must apply through Access Health CT (the State-based Marketplace) either online or by phone and can be determined eligible for full-scope Medicaid, the Marketplace or the family planning program. The vast majority (>90%) of family planning program enrollees originally entered the program by applying for presumptive eligibility at the Planned Parenthood of Southern New England affiliate.

Enrollment in the family planning program beyond the presumptive eligibility period has fallen from 361 individuals in July 2015 to 274 individuals in June 2016. This decline is primarily the result of individuals obtaining full coverage through the Marketplace or in full-scope Medicaid.

Intersection with Medicaid Managed Care: Connecticut no longer operates a Medicaid managed care program. In 2012, Connecticut’s Medicaid program transitioned from contracting with managed care organizations (MCOs) for the delivery of care to fee-for-service, leveraging several Administrative Service Organizations (ASOs) to help with program administration.

LARC: LARC methods are included in the family planning program benefit package. The State also promotes LARC insertions for post-partum women immediately following delivery by allowing hospitals to bill for immediate post-partum LARC outside of inpatient delivery codes.

Other Initiatives: None identified

Delivery System Reform:In December 2014, CMS’ Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation awarded Connecticut up to $45 million through a State Innovation Model grant to implement the Connecticut Healthcare Innovation Plan. While the Innovation Plan does not include any family planning-specific components, family planning providers have been invited to participate in some programs. Back to top

Illinois State Profile

Family Planning Overview: Illinois does not have a separate Family Planning waiver or State Plan Amendment for the provision of family planning services. Instead, Illinois embeds family planning and family-planning related services within Medicaid’s comprehensive benefit package. The Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services (HFS) administers the full Medicaid program, with the Bureau of Quality Management overseeing family planning services, among other initiatives, within the broader Medicaid Program.

Illinois Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Levels as % of FPL66 Eligibility levels do not include 5% income disregard

| Children by Age (Medicaid) | Separate CHIP | Pregnant Women(Medicaid) | Parents | Childless Adults |

| 0-1 | 1-5 | 6-18 |

| 142% | 142% | 142% | 313% | 208% | 133% | 133% |

Share of Medicaid Population Covered by Different Delivery Systems67

| % of Medicaid Population Covered |

| Fee-for-Service | 21% |

| Primary Care Case Management | 27% |

| Managed Care Organizations | 53% |

Brief Program History: Between 2004 and 2014, the State operated the “Illinois Healthy Women” family planning waiver for women ages 19-44 with incomes up to 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL). The program was administered through the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health Promotion (BMCHP) within HFS. Illinois ended its family planning waiver program on December 31, 2014 with the understanding that women enrolled in the waiver would have the opportunity to enroll in comprehensive coverage — either in Medicaid expansion (for those with incomes at or below 138% of the FPL) or in a qualified health plan with financial assistance on the Marketplace (for those with incomes between 138% FPL and 200% FPL). BMCHP was recently merged into the Bureau of Quality Management.

After Illinois decided to end the waiver program, the State was granted a “transition year” across 2014 to conduct outreach to enrollees, educating them about the closing of the program and opportunities to enroll in either full coverage Medicaid or a Marketplace Qualified Health Plan (QHP) with premium tax credits. While waiver enrollees could not be automatically enrolled into the Medicaid expansion program because the State’s system did not capture enrollees’ income as a percentage of FPL, State data indicate that 45% of waiver enrollees had transitioned to full coverage Medicaid as of February 2016. A portion of waiver enrollees most likely gained coverage in the Marketplace QHPs, although information on the number of enrollees is not available.

Medicaid Enrollee Access to Family Planning Benefits: Medicaid enrollees have access to family planning services as a part of their comprehensive Medicaid benefit package. The majority of enrollees likely to seek family planning services are enrolled in Medicaid managed care.

In June 2014, Illinois Medicaid released a new policy providing guidance to all Medicaid-enrolled providers regarding comprehensive quality family planning and reproductive health services. In October 2014, Illinois took a step to increase access to family planning services, and most notably LARC methods, by increasing Medicaid reimbursement rates for the following procedures:68

| CPT Code | Description | Previous Rate | New Rate |

| 11981 | Insertion of implant | $72.30 | $88.00 |

| 11982 | Removal of implant | $87.00 | $99.00 |

| 11983 | Removal and reinsertion of implant | $108.00 | $143.00 |

| 58300 | Insertion of IUD | $44.00 | $88.00 |

| 58301 | Removal of IUD | $37.40 | $37.40 |

| 58300 + 58301 | Removal and reinsertion of IUD | $44.00 | $106.70 |

Intersection with Managed Care: In 2015, Illinois’ Medicaid program transitioned from predominantly fee-for-service to over 50% managed care. Knowing that the family planning enrollees transitioning to full coverage Medicaid would be enrolled in Medicaid MCOs, the State rolled out the “Family Planning Action Plan”69 (FPAP) to help smooth the transition and ensure that enrollees continued to receive access to comprehensive family planning services. The FPAP articulates for providers and MCOs that:

- All Medicaid providers must offer the full spectrum of family planning contraceptives with no cost sharing, step therapy or prior authorization;

- The Free Choice of Provider statute allows enrollees to see any Medicaid provider regardless of managed care network status; and

- Enrollees should receive education and counseling on all FDA-approved contraceptives, from most to least effective, with most effective including long acting reversible contraceptives (LARC)—intrauterine devices (IUD) and the contraceptive implant.

- The Medicaid agency oversees MCOs and their provision of family planning services. In addition to contracting requirements, the Medicaid agency:

- Requires MCO attendance at periodic in-person meetings, during which the Medicaid agency communicates updates, critical program information, and provides trainings, including on family planning services and how to improve birth outcomes;

- Requires MCOs to provide intensive care management to enrollees under the prenatal care plan which includes family planning education and counseling; and

- Is in the process of updating its methodology for withholding a portion of MCOs’ capitation rates contingent on their meeting certain performance measures. Consideration will be given to family planning metrics when the updated developmental contraceptive performance measures are finalized.

LARC: Illinois has implemented several policy and payment changes to increase access to LARC. In addition to the coverage and counseling requirements outlined in the FPAP, Illinois has: (1) increased reimbursement for insertion, removal and reinsertion of LARCs in outpatient settings; (2) increased the dispensing fee for LARC purchased through the 340B program; (3) allowed separate reimbursements for an Evaluation & Management visit in which the provider and patient discuss contraceptive options and a same-day LARC procedure; (4) allowed hospitals to separately bill for a LARC device that is provided immediately postpartum in the inpatient hospital setting;70 (5) ensured that federally-qualified health centers and rural health centers receive reimbursement for actual acquisition costs for LARC devices under the 340B program separate from the encounter rate; and (6) implemented a pilot program to ensure outpatient providers maintain sufficient supplies of LARC methods.71

Other Initiatives: Illinois has deployed other payment and billing changes across fee-for-service and managed care to ensure access to a range of contraceptive methods, including:

- Increasing the reimbursement rate for vasectomies;

- Permitting FQHCs and RHCs to bill fee-for-service for transcervical sterilization devices, which the State describes as alternatives to hospital-based surgical sterilization that do not require incisions or general anesthesia;

- Establishing a contraceptive education/counseling enhanced rate for eligible providers;

- Increasing medical dispensing fee add-ons for certain 340B birth control methods beyond LARC; and,

- Requiring providers to dispense three month supplies of certain contraceptives whenever possible and medically appropriate.

Additionally, on July 29, 2016, Governor Bruce Rauner signed into law House Bill 5677,72 which ensures that all FDA-approved contraceptive drugs, devices and supplies are covered without cost-sharing by individual and group plans regulated by the state or that cover state employees, retirees and their dependents. While plans are not required to include all FDA-approved, therapeutic equivalents of a drug, device or product on formulary, plans must make available without cost-sharing any off-formulary methods recommended by a patient’s provider based on medical necessity. The bill also ensures that 12 months’ worth of contraception may be dispensed at one time and requires coverage for patient education, counseling on contraception, contraceptive follow-up services and voluntary sterilization procedures. The law is scheduled to take effect January 1, 2017.

Finally, the Illinois Medicaid agency contributed to the national effort among the federal Department of Health and Human Services Office of Population Affairs, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to develop contraceptive use performance measures.

Delivery System Reform: There are no new statewide delivery system reform efforts underway. Back to top

Missouri State Profile

Family Planning Overview: Missouri administers its family planning program through an 1115 waiver for uninsured women ages 18-55 with incomes at or below 201% FPL. Enrollees in the program are covered for both family planning and family planning-related services. The program is co-managed by two divisions within the Department of Social Services: MO HealthNet (Missouri’s Medicaid agency) and the Family Support Division (FSD). FSD manages program eligibility and MO HealthNet handles policy and claims administration.

Missouri Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Levels as % of FPL73 Eligibility levels do not include 5% income disregard

| Children by Age (Medicaid) | Separate CHIP | Pregnant Women(Medicaid) | Parents | Childless Adults |

| 0-1 | 1-5 | 6-18 |

| 196% | 148% | 148% | 300% | 196% | 18% | N/A |

Share of Medicaid Population Covered by Different Delivery Systems74

| % of Medicaid Population Covered |

| Fee-for-Service | 50% |

| Managed Care Organizations | 51%75 |

Brief Program History: Missouri’s initial family planning program was approved as part of an 1115 Medicaid managed care demonstration project, which ran from May 1, 1998 through March 1, 2004, before being extended through September 30, 2007. On October 1, 2007 Missouri implemented the current family planning program entitled “Women’s Health Services Program.” At the request of the State, CMS subsequently renewed and extended this program through December 31, 2014, then again through December 31, 2017. Missouri did not see a need to transition the waiver program to a State Plan Amendment. Program enrollment has grown from an average monthly enrollment of approximately 60,000 in 2013 to approximately 71,000 in 2016.

Missouri recently suspended the family planning waiver and replaced it with a state-funded program titled “Missouri Women’s State-Funded Health Service Program.” All existing waiver program enrollees will be automatically transitioned into the state-funded program. Program eligibility and benefits are expected to remain the same. This change is being made because language authorizing funding for the program no longer complies with all terms and conditions of the waiver. As passed by the legislature76 and described in the State’s Public Notice,77 Medicaid funds in Missouri will no longer be “expended to directly or indirectly subsidize abortion services or procedures or administrative functions and none of the funds…may be paid or granted to an organization that provides abortion services.”

Program Enrollment: Missouri employs the same application, verification, and renewal processes for full-scope Medicaid and the family planning program. Pregnant women enrolled in Medicaid are automatically enrolled into the family planning program 60 days postpartum.

Intersection with Medicaid Managed Care: Half of Missouri’s full-scope Medicaid enrollees are enrolled through a Medicaid managed care plan. Family planning benefits are aligned across the family planning waiver program, Medicaid fee-for-service (FFS) and Medicaid managed care plans. Medicaid managed care plans in Missouri are required to offer care management for individuals receiving family planning services and to contract with Title X and other family planning providers. Additionally, plans must have internal quality improvement procedures for a variety of clinical areas, including family planning, well-woman care, and maternity.

LARC: LARC methods are included in the family planning program benefit package. Missouri recently expanded access to LARC for both Medicaid and family planning program enrollees by separately reimbursing hospitals for LARC insertions for post-partum women immediately following delivery.78

Other Initiatives: None identified

Delivery System Reform: Missouri is not currently pursuing delivery system reform efforts; however, Missouri will be expanding Medicaid managed care eligibility criteria by May 2017, with the primary goal of transitioning more children into managed care plans. The family planning program will remain FFS. Back to top

Virginia State Profile

Family Planning Overview: Virginia administers its “Plan First” program though a State Plan Amendment (SPA) for women and men of any age with incomes up to 200% FPL. Enrollees in Plan First have coverage of family planning services, but not family planning related services. The Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS) administers the Plan First program and contracts with the local Department of Social Services to perform eligibility determinations and enrollment of members in Plan First. The Department of Health (VDH) is the largest provider of safety-net family planning services through its Title X clinics.

Virginia Medicaid/CHIP Eligibility Levels as % of FPL79 Eligibility levels do not include 5% income disregard

| Children by Age (Medicaid) | Separate CHIP | Pregnant Women*(Medicaid) | Parents | Childless Adults |

| 0-1 | 1-5 | 6-18 |

| 143% | 143% | 143% | 200% | 143% | 49% | 0% |

| *Virginia also has a Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability CHIP waiver that covers pregnant women over the Medicaid income limits up to 200% of FPL. |

Share of Medicaid Population Covered by Different Delivery Systems80

| % of Medicaid Population Covered |

| Fee-for-Service | 34% |

| Managed Care Organizations | 66% |

Brief Program History: Virginia first established a family planning program through a waiver in 2002. This Medicaid waiver extended family planning services for two years to Medicaid pregnant women enrollees after delivery, if they continued to meet eligibility requirements. In 2007, coverage was expanded to all women and men with incomes less than 133% FPL and the lower age requirement of 19 was removed. The income limit was then raised to 200% FPL in 2008. In 2011, Virginia transitioned the family planning program from a waiver to a State Plan, eliminating the need for demonstration renewals every three years as well as waiver evaluations and reports. Since Virginia converted to a State Plan, the requirement for individuals to complete a separate application for family planning upon losing full-scope Medicaid coverage was removed, thus enrollment increased substantially from 8,000 in 2011 to approximately 110,000 in 2016. Notably, the State has not seen a corollary increase in utilization of services in Plan First, reflecting that many of the enrollees are not using services.

Program Enrollment & Access to Care: As part of the Affordable Care Act, Virginia uses a single, streamlined application for most Medicaid eligibility categories, including Plan First. Prior to implementation of the single, streamlined application, Virginia used a shorter, family planning-only form. Individuals between the ages of 19 and 64 who apply for Medicaid using the streamlined application who are not found eligible for full-scope Medicaid but are determined eligible for Plan First are automatically enrolled, unless they opt out for Plan First determination. Individuals under age 19 and over 64 must opt in to be evaluated for the Plan First program if they are not determined eligible for a full Medicaid covered group.

Plan First enrollees may obtain family planning services from any Department of Medical Assistance Services (DMAS) enrolled fee-for-service provider.

Intersection with Medicaid Managed Care: Two-thirds of Virginia’s Medicaid enrollees with comprehensive coverage are enrolled in a Medicaid managed care plan. Family planning services are included in the comprehensive benefit package and are very similar to those offered to family planning SPA enrollees. DMAS is evaluating programmatic differences and working to align the programs.

LARC: Virginia is working on reforms to eliminate payment barriers and increase access to and utilization of LARC in a variety of settings, including physician offices and hospital-based immediate postpartum LARC insertion. The Virginia DMAS is working with the Virginia Department of Health (VDH), Physician and Nurse Practitioner Provider Associations, and the Medicaid and CHIP managed care health plans to increase provider and member education as well as outreach efforts on the benefits of LARC and processes needed to streamline reimbursement for the LARC devices.

Other Initiatives: Virginia has taken steps to address Plan First enrollment issues and increase access to contraception, including through the following activities:

- DMAS and VDH jointly conducted targeted outreach to encourage enrollment into the Plan First program for several years. Each agency received funding to devote staff to these efforts, including outreach to patients and providers, and met regularly to discuss the outcomes of these efforts.

- DMAS modified the Plan First ID card and member handbook to differentiate the program more clearly from Medicaid, resolving confusion among providers and consumers about whether women had family planning only or full-scope Medicaid.

- While all categories of contraceptives are covered, in 2016 Virginia increased access to oral contraceptive methods by eliminating it from the “preferred drug list” (PDL). Removing contraceptives from the PDL removes all prior authorization requirements from oral contraceptives since the Commonwealth does not have “non-preferred” agents. Currently, physician-administered contraceptive methods are not on the PDL and must be purchased by the practitioner and billed upon administration.

- In 2015, VDH dedicated funding to increase accessibility of LARCs as part of an initiative to reduce unintended pregnancy. VDH continues to support availability of LARCs for VDH clients as long as funding allows. The intent is to compare statewide unintended pregnancy rates before 2015 and after this 2015 LARC initiative to measure efficacy and LARC selection by clients.

Delivery System Reform: In February 2016, Virginia submitted an 1115 Medicaid waiver application to CMS requesting authority to implement a $1 billion Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) initiative. The initiative would establish networks of high performing providers that would partner with managed care organizations to improve and coordinate care and ultimately transition to new payment models for high-cost Medicaid enrollees. Family planning providers and metrics were not incorporated into the proposed demonstration. Back to top

Appendix C: List of Interviewees

ALABAMA

Medicaid Agency:

Gretel Felton, Deputy Commissioner for Beneficiary Services

Jerri Jackson, Director of the Managed Care Division

Sylisa Lee-Jackson, Associate Director of Maternity, Plan First/Family Planning, and Nurse Midwife Programs

Department of Public Health, Bureau of Family Health Services:

Meredith Adams, Director of Social Work

Diane Beeson, Director of Women’s and Children’s Health Division

Leigh Ann Hixon, Plan First Manager

CALIFORNIA

Department of Health Care Services (DHCS):

Nicole Griffith, Assistant Division Chief of the Office of Family Planning (OFP)

René Mollow, Deputy Director of Healthcare Benefits and Eligibility

Christina Moreno, Division Chief, OFP

Laurie Weaver, Assistant Deputy Director of Healthcare Benefits and Eligibility

University of California at San Francisco (UCSF)

Claire Brindis, Professor of Pediatrics and Health Policy and Director of the Institute for Health Policy Studies. Previously, lead of UCSF Family PACT Evaluation, OFP, DHCS

Heike Thiel de Bocanegra, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology & Reproductive Services. Previously, director of UCSF Family PACT Evaluation, OFP, DHCS

Dr. Christine Dehlendorf, Associate Professor, School of Medicine

University of California, Davis

Eleanor Schwarz, Professor of Medicine. Previously, medical director of UCSF Family PACT Evaluation, OFP, DHCS

Planned Parenthood Affiliates of California:

Kathy Kneer, President and CEO

California Family Health Council:

Amy Moy, Vice President of Public Affairs

Julie Rabinowitz, President and CEO

CONNECTICUT

Department of Social Services:

Nina Holmes, Health Program Supervisor, Division of Health Services

Daniel Patterson, Public Assistance Consultant, Eligibility Policy and Program Support

Mark Shock, Director of Eligibility Policy, Division of Health Services

Robert Zavoski, Medical Director, Division of Health Services

Planned Parenthood of Southern New England:

Susan Lane, Director of Planning and Grants

Judy Tabar, President and CEO

ILLINOIS

Department of Healthcare and Family Services

Mary Doran, Bureau Chief, Bureau of Program and Policy Coordination

Teresa Hursey, Acting Administrator, Division of Medical Programs

Linda Wheal, Maternal Health Program Manager, Bureau of Quality Management

Chicago Department of Public Health:

Kai Tao, Deputy Commissioner, Chief Program Officer

Planned Parenthood of Illinois:

Brigid Leahy, Director of Public Policy

EverThrive:

Kathy Waligora, Director Health Reform Initiative

University of Chicago, Center for Interdisciplinary Inquiry and Innovation in Sexual and Reproductive Health:

Lee Hasselbacher, Policy Coordinator, Family Planning and Contraceptive Research

MISSOURI

MO HealthNet:

Glenda Kremer, Assistant Deputy Director of the Program Operational Unit

Nancy Nikodym, Social Services Unit Manager

Jayne Zemmer, Assistant Deputy Director of Clinical Services Policy & Operations

Department of Social Services (DSS):

Jennifer Tidball, Deputy Director

Kim Evans, Deputy Director for Income Maintenance, Family Support Division

St. Louis Planned Parenthood:

Mary Kogut, Chief Executive Officer

Angie Postal, Director of Public Policy

Missouri Family Health Council:

Michelle Trupiano, Executive Director

Missouri Foundation for Health:

Thomas McAuliffe, Director of Health Policy

Contraceptive Choice Center at the Washington University in St. Louis:

Dr. Tessa Madden, OB-GYN and Assistant Professor at the School of Medicine

Dr. Timothy McBride, Professor at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work

VIRGINIA

Department of Medical Assistance Services

Ashley Harrell, Policy & Services Manager, Maternal & Child Health Division

William Lessard, Director of Provider Reimbursement

Linda Nablo, Chief Deputy Director

Daniel Plain, Senior Health Care Services Manager

Cheryl Roberts, Deputy Director for Programs

Department of Health:

Sulola Adekoya, Medical Director for Regional Health Services

Janelle Anthony, Family Planning Quality Assurance Nurse

Cornelia Deagle, Director of the Division of Children and Family Health

Richmond City Health District:

Danny Avula, Deputy Director

Laurinda Davis, Public Health Nurse Supervisor

Planned Parenthood Advocates of Virginia:

Cianti Stewart-Reid, Executive Director

The Virginia League for Planned Parenthood:

Paulette McElwain, President and CEO

Virginia Poverty Law Center:

Jill Hanken, Health Attorney

FEDERAL & NATIONAL EXPERTS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS): Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS), State Demonstrations Group:

Andrea Casart, Director, Division of Medicaid Expansion Demonstrations

Julie Sharp, Technical Director, Division of State Demonstrations and Waivers

CMS: CMCS, Children and Adults Health Programs Group:

Stephanie Bell, Deputy Director, Division of Eligibility & Enrollment

Lekisha Daniel-Robinson, Coordinator, Maternal and Infant Health Initiative, Division of Quality and Health Outcomes

Karen Mizuka, Chief Quality Officer, Division of Quality and Health Outcomes

Jennifer Sheer, Project Officer, Division of Quality and Health Outcomes

CMS: CMCS, Office of the Administrator:

Jessica Schubel, Senior Policy Advisor to the Director of CMCS

National Family Planning and Reproductive Health Association:

Clare Coleman, CEO

Robin Summers, Policy Director

Planned Parenthood Federation of American:

Carolyn Cox, Public Policy Manager

Sarah Gillooly, Strategic Manager for Health Finance

Davida Silverman, Senior Policy Analyst

Emily Stewart, National Director of Public Policy

Amy Yenyo, Assistant Director of Public Policy