The Landscape of Medicaid Demonstration Waivers Ahead of the 2020 Election

Issue Brief

Key Takeaways

As the Trump administration reaches the end of its first term, this issue brief considers the landscape of approved and pending Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers under this administration and how the November 2020 presidential election may impact this landscape. Section 1115 waivers offer states an avenue to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from what is required by federal statute and can provide states considerable flexibility in how they operate their programs. States can also use waivers to respond to emergencies. In March 2020, the Trump administration released guidance for states to obtain emergency COVID-19 waivers in response to the pandemic.

Section 1115 waivers generally reflect priorities identified by the states and the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), as well as changing priorities from one presidential administration to another. Beginning in the 1990s, there was an increase in waiver activity, and waivers became broader in scope. Under different administrations in the past, waivers have been used to expand coverage, modify delivery systems, and restructure financing and other program elements. Although each administration has some discretion over which waivers to approve and encourage, that discretion is not unlimited.

The Trump administration’s Section 1115 waiver policy has emphasized work requirements and other eligibility restrictions, payment for institutional behavioral health services, and capped financing. The Trump administration has aimed to reshape the Medicaid program (e.g. financing, eligibility, and benefits) through the use of Section 1115 demonstration waivers. Although waiver submission and approval activity initially slowed in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic downturn, CMS has resumed issuing approvals with work requirements and other restrictions in the weeks ahead of the November 2020 election.

The future landscape of Section 1115 waivers depends on both the outcome of the November 2020 presidential election as well as the result of ongoing legal challenges to certain waivers. Section 1115 waivers generally reflect administrative priorities. Former Vice President Joe Biden is supportive of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion and has proposed using a federal public option to cover low-income Americans in states that have not expanded. While Biden’s formal campaign proposals have been silent on Medicaid waivers, if he wins the election he would have the authority to rescind existing CMS guidance and/or issue new guidance and could also withdraw already-approved waiver and/or expenditure authorities. If President Donald Trump wins a second term, his administration would presumably continue existing waiver priorities. The Trump administration is seeking Supreme Court review of appeals court decisions which found work requirement waivers in Arkansas and New Hampshire to be unlawful. Other waiver approvals under the Trump administration—such as any approved changes to financing structures—may similarly face legal challenges.

Introduction

As of October 2020, 44 states had a total of 57 approved Section 1115 Medicaid waivers, while 21 states had a total of 26 pending waivers (including new waiver requests and pending extensions of or amendments to existing approved waivers). These waivers range across a variety of categories and offer states flexibility to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from what is required by federal statute. In general, waivers reflect priorities identified by states as well as changing priorities from one presidential administration to another. For example, the Trump administration has aimed to make sweeping changes to Medicaid using Section 1115 demonstration waivers, including provisions not previously approved by any administration.

This brief explores three key questions about the landscape of Section 1115 Medicaid waivers ahead of the 2020 election:

- What are Section 1115 waivers and how have they been used in the past?

- What are key waiver themes under the Trump administration?

- What might the future landscape of waivers look like?

What are Section 1115 Medicaid Waivers?

Section 1115 Medicaid demonstration waivers offer states an avenue to test new approaches in Medicaid that differ from what is required by federal statute. They can provide states additional flexibility in how they operate their programs, beyond the considerable flexibility that is available under current law. Waivers generally reflect priorities identified by states and the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), as well as changing priorities from one presidential administration to another. Each administration has some discretion over which waivers to approve and encourage (see Figure 1 and Appendix A), but that discretion is not unlimited—for example, in February 2020, a unanimous federal appeals court upheld a district court decision that set aside the Trump administration’s work requirement waiver approval in Arkansas. The Trump administration is seeking Supreme Court review of this case. The most current state-by-state activity is contained in the KFF Medicaid waiver tracker,1 which shows approved and pending waivers.

Authority and Purpose. Under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, the Secretary of HHS can waive specific provisions of major health and welfare programs, including certain requirements of Medicaid and CHIP. Section 1115 permits the Secretary to allow states to use federal Medicaid and CHIP funds in ways that federal rules do not otherwise allow, as long as the Secretary determines that the initiative is an “experimental, pilot, or demonstration project” that “is likely to assist in promoting the objectives of the program.”2 States can obtain “comprehensive” Section 1115 waivers that make broad changes in Medicaid eligibility, benefits, provider payments, and other program rules across their programs.3 While the Secretary’s waiver authority is broad, it is not unlimited. The Secretary does not have authority to waive some elements of the program, such as the federal matching payment system for states, or requirements that are rooted in the Constitution, such as the right to a fair hearing.4 Additionally, as an appeals court recently affirmed in the case challenging Arkansas’s work requirement waiver, the Secretary must use Section 1115 authority to further Medicaid’s primary objective as set out by Congress: providing affordable health insurance coverage.

Financing. While not set in statute or regulation, a longstanding component of Section 1115 waiver policy is that waivers must be budget neutral for the federal government. As such, federal costs under a waiver must not exceed what federal costs would have been for that state without the waiver, as calculated by the administration. To date, the federal government generally enforces budget neutrality by establishing a per member per month cap on federal funds under the waiver, putting the state at risk for increases in per member per month costs but not for increased costs due to enrollment growth.5

Transparency, Public Input, and Evaluation. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) made Section 1115 waivers subject to new rules about transparency, public input, and evaluation. In February 2012, HHS issued regulations that require public notice and comment periods to occur at the state and federal levels before CMS approves new Section 1115 waivers and extensions of existing waivers.6 Although the final regulations on public notice do not require a state-level public comment period for amendments to existing/ongoing demonstrations, CMS has historically applied these regulations to amendments as well.7 The ACA also implemented new evaluation requirements for Section 1115 waivers, including that states must have a publicly available, CMS-approved evaluation strategy.8 States have traditionally been required to submit quarterly reports as well as an annual report to HHS that describes the changes occurring under the waiver and their impact on access, quality, and outcomes.9 ,10 Since taking office, the Trump administration has established new guidelines for waiver approval, reporting and evaluation, and renewals (Box 1). Notably, required rules related to transparency, public input and evaluation would be set aside should the Supreme Court invalidate the ACA.

Box 1. Trump Administration Changes to Waiver Approval, Reporting and Evaluation, and Renewal Periods.

New Waiver Approval Criteria. Marking a new direction for Medicaid waivers, in November 2017, CMS posted revised criteria for evaluating whether Section 1115 waiver applications further Medicaid program objectives (see Appendix B).11 The revised criteria no longer include expanding coverage among the stated objectives. Instead, the revised waiver criteria focus on positive health outcomes, efficiencies to ensure program sustainability, coordinated strategies to promote upward mobility and independence, incentives that promote responsible beneficiary decision-making, alignment with commercial health plans, and “innovative” payment and delivery system reforms.

Reporting and Evaluation. CMS released an Informational Bulletin in November 2017 signaling an interest in reducing the frequency of required state reporting from quarterly to semi-annual or annual for certain demonstrations. CMS’s August 2017 renewal of Florida’s Managed Medical Assistance Section 1115 waiver allows the state to submit annual reports (and semi-annual reports at CMS’s request) instead of quarterly reports.

Renewal Periods. In guidance released in November 2017, CMS indicated that it would consider approving “routine, successful, non-complex” Section 1115 waiver extension requests for up to 10 years.12 Most recently, on October 26, 2020, CMS approved Indiana’s request to extend many components of its existing HIP 2.0 waiver for 10 years, including premiums with disenrollment for nonpayment, conditioning the start of coverage upon first premium payment, a tobacco use premium surcharge, and elimination of retroactive eligibility and non-emergency medical transportation.13 As of October 2020, CMS is still working with Indiana to incorporate and extend for 10 years its “bridge account” amendment. On December 28, 2017, CMS approved the first 10-year extension with its extension of the Mississippi Family Planning Medicaid Waiver. Since then, CMS has approved 10-year waiver extensions for non-family planning demonstrations, with both Maine’s HIV/AIDS extension approval and Wisconsin’s SeniorCare extension approval issued in April 2019.

What are Key Waiver Themes under the Trump Administration?

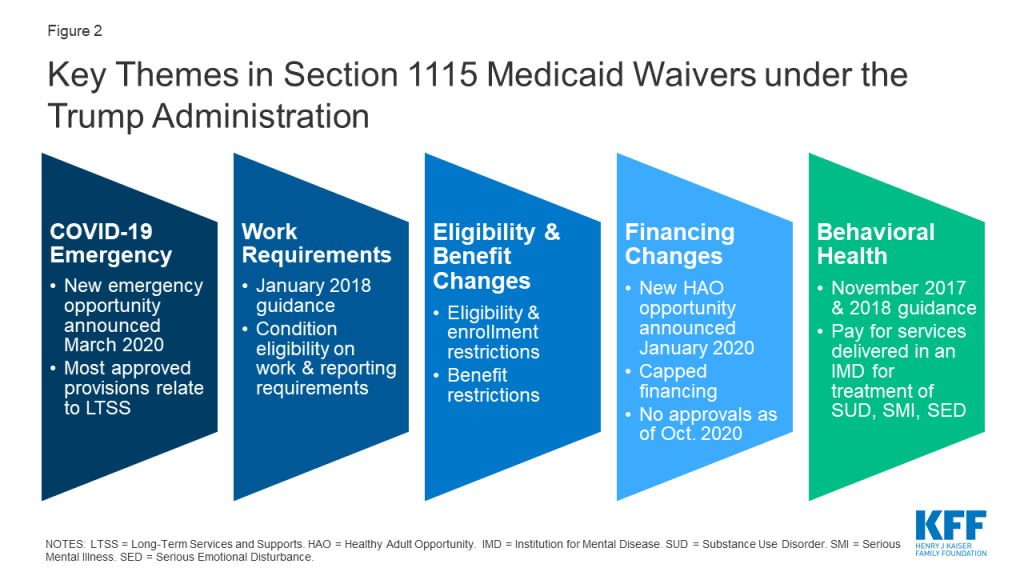

The Trump administration has aimed to make sweeping changes to Medicaid using Section 1115 demonstration waivers. While Congress fell short of passing legislation in 2017 to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and to reduce and cap federal Medicaid financing, the Trump administration sought to make sweeping changes to Medicaid through the use of Section 1115 demonstration waivers as well as other administrative channels, including rulemaking and sub-regulatory policy guidance. CMS under the Trump administration has prioritized several areas of focus for Section 1115 waivers, some of which represent reversals of or departures from previous administrations’ policies (Figure 2). In particular, the Trump administration’s waiver policy has emphasized waivers that allow states to:

- Respond to the COVID-19 pandemic using emergency waivers.

- Condition Medicaid eligibility on meeting work requirements.

- Impose restrictions on eligibility, enrollment, and benefits.

- Not apply an array of federal rules in exchange for capped financing, as proposed under guidance inviting Health Adult Opportunity (HAO) demonstrations.

- Receive federal Medicaid funds for services delivered in an “institution for mental disease” for treatment of substance use disorder or serious mental illness.

Waiver submission activity has slowed, however, in the face of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) and associated economic downturn. No states have newly requested waivers with work requirements, other eligibility and enrollment restrictions, or financing changes since February 2020. To access enhanced federal Medicaid funding during the PHE, states must meet “maintenance of eligibility” (MOE) conditions which limit state options to enforce new eligibility and enrollment restrictions. These conditions include ensuring continuous eligibility for current enrollees and prohibit states from increasing premiums or making eligibility standards, methodologies, or procedures more restrictive than those in effect on January 1, 2020, among other requirements. Further, some states are utilizing Medicaid emergency authorities to take additional actions to address the pandemic including expanding eligibility and making it easier to apply such as allowing for self-attestation of eligibility criteria; eliminating premiums; expanding the use of presumptive eligibility; and otherwise simplifying application processes. State interest in pursuing Medicaid financing changes that could shift fiscal risk to states such as the HAO option has been limited to date and is not expected to increase, given that the pandemic and economic downturn has resulted in increased Medicaid enrollment, adverse state budgetary impacts, and uncertainty about the future. Despite the slowdown in overall state waiver submission activity, in the weeks ahead of the November 2020 presidential election CMS approved new waivers in expansion (Nebraska) and non-expansion states (Georgia) with work requirements, eligibility, and benefit restrictions.

The following sections highlight major policy guidance, waiver decisions, and litigation challenges across several waiver categories. (For the most up-to-date list of pending and approved COVID-19 emergency waivers, see the KFF Medicaid emergency authorities tracker; for the most up-to-date list of other Section 1115 waivers, see the KFF Medicaid waiver tracker.)

COVID-19 Public Health Emergency

In response to the COVID-19 PHE, on March 22, 2020 CMS released a new Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration opportunity and application template intended to enable states to protect the health, safety, and welfare of individuals and providers affected by COVID-19. This template allows states to extend home and community-based services (HCBS) flexibilities available under Section 1915 (c) HCBS Appendix K to beneficiaries receiving long-term services and supports (LTSS) under state plan authorities. To further expedite the provision of services during the PHE, the template also allows states to accept applicant self-attestation of income and assets for the purpose of determining eligibility for individuals seeking LTSS. There are requirements for monitoring and evaluation, but CMS is not requiring states to submit calculations showing that the waiver would be budget neutral to the federal government like traditional waivers due to the emergency nature of the pandemic. These demonstrations can be retroactive to March 1, 2020 and will expire no later than 60 days after the end of the PHE (which is currently set to end on January 21, 2021).

To date, CMS has approved emergency COVID-19 Section 1115 waivers for eight states, although state websites indicate that many more states have submitted requests for these waivers.14 Most approved provisions relate to LTSS and follow the “pre-printed” waiver and expenditure authorities outlined in the CMS template. The most commonly-approved provision is the ability to make retainer payments to certain habilitation and personal care providers to maintain capacity during the public health emergency (five states are approved for this authority). Historically, states have used Section 1115 authority to expand coverage and/or provide uncompensated care to address the direct impact of natural disasters and public health emergencies (like New York City after 9/11, Hurricane Katrina, and Flint Michigan) on state Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) programs; however, CMS has not approved similar requests in emergency COVID-19 waivers. For example, CMS did not approve Washington’s request to establish a temporary eligibility group for individuals with incomes at or below 200% FPL.15 CMS also noted in its April 2020 approval of Washington’s request that it was continuing to review the state’s request to create a Disaster Relief Fund to cover costs associated with the treatment of uninsured individuals with COVID-19, housing, nutrition supports, and other COVID related expenditures, but no additional approvals have been granted to date.

Work Requirements / Community Engagement

In January 2018, CMS issued guidance for Section 1115 waiver proposals that impose work and reporting requirements (referred to as community engagement) as a condition of Medicaid eligibility. This action reversed the positions of previous Democratic and Republican administrations, which had not approved such waiver requests on the basis that they would not further the Medicaid program’s purposes of promoting health coverage and access. The January 2018 guidance argues that such provisions would promote program objectives by helping states “in their efforts to improve Medicaid enrollee health and well-being through incentivizing work and community engagement.” In its HAO guidance, CMS also included work requirements as a policy provision that it would approve in those waivers.

As of October 2020, eight states have approved waivers with work requirements, seven have such waiver requests pending, and four other states (AR, KY, MI, and NH) have had work requirement waivers set aside by the courts; however, no states are currently implementing work requirements. After taking office in December 2019, Kentucky’s Governor rescinded the state’s waiver that the district court had set aside, and the appeals court case has been dismissed. States with approved waivers not set aside by courts have not yet implemented them (GA, NE, OH, SC, and WI) or have put implementation on hold due to pending litigation (AZ16 and IN17 ) or due to the coronavirus pandemic (UT18 ). In February 2020, a federal appeals court upheld the district court decision that set aside the work requirement waiver in Arkansas; in May 2020, the appeals court decided that the reasoning of its Arkansas decision required a similar outcome in a case challenging New Hampshire’s waiver approval. The court cited the Secretary’s failure to consider the waiver’s impact on Medicaid’s primary objective of providing affordable health coverage. These appeals court decisions—for which the administration is seeking Supreme Court review—could have implications for pending legal challenges to work requirements in other states. While these decisions did not directly invalidate work requirement approvals in other states, courts hearing similar cases are likely to consider these decisions when deciding challenges to other waiver approvals. To date, Arkansas is the only state to have implemented a waiver that conditioned Medicaid eligibility on meeting a work and reporting requirement, which resulted in over 18,000 people losing coverage from its implementation in summer 2018 by the end of that year before the waiver approval was set aside by the court.

Despite legal challenges, CMS has continued to approve work requirement waivers, including requirements that apply to low-income parents and others in non-expansion states (GA and SC) and a waiver that conditions access to certain benefits for expansion enrollees on meeting a work requirement (NE). CMS approved the first work requirement waiver for low-income parents and caretaker relatives in a non-expansion state, South Carolina, in December 2019. The waiver will apply primarily to low-income parents and is the first work requirement waiver to mandate that all new applicants comply with work requirements at the time of application to be enrolled in coverage.19 In October 2020, CMS approved a similar work requirement waiver for Georgia, another non-expansion state. Georgia’s waiver will apply to low-income parents and childless adults not otherwise eligible for Medicaid and, like South Carolina’s, conditions initial and continued enrollment on work requirement compliance.20 Also in October 2020, CMS approved Nebraska’s request to require non-exempt expansion beneficiaries to meet work and other requirements in order to access certain state plan benefits (over-the-counter medication, vision, and dental coverage).21

Eligibility and Benefit Changes

States are implementing a range of demonstrations that include eligibility restrictions, some of which were approved for the first time under the Trump administration. Under the Obama administration, CMS approved certain eligibility- and enrollment-related waiver provisions as part of ACA Medicaid expansion waivers (e.g., charging premiums beyond what is allowed under federal law, eliminating retroactive eligibility for certain populations, making coverage effective on the date of the first premium payment instead of the date of application, and locking out certain expansion adults who are dis-enrolled for unpaid premiums). Under the Trump administration, CMS has allowed states to apply these previously approved provisions as well as new eligibility and enrollment restrictions to both expansion and traditional Medicaid populations (e.g., low-income parent/caretakers) (see KFF waiver tracker for details).

Prior to the pandemic, CMS approved the following eligibility and enrollment restrictions for the first time under the Trump administration:22

- Coverage lock-outs for failure to timely renew coverage or report changes affecting eligibility and for non-payment of premiums for non-expansion populations.

- Authority to charge premiums up to 5% of family income and to impose a premium surcharge for tobacco users.

- Elimination of retroactive coverage for nearly all Medicaid enrollees, including seniors and people with disabilities.23

- Eligibility conditioned on the completion of a health risk assessment (HRA).

The current administration has also approved waivers that affect enrollees’ access to benefits and free choice of family planning providers. While the Obama administration had approved some benefit restriction provisions as part of ACA expansion waivers, the Trump administration has approved them for both expansion and non-expansion populations. Approved benefit restrictions under the current administration include elimination of non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) and implementation of healthy behavior incentives (tied to premium or cost-sharing reductions). Nebraska has also received approval to require beneficiaries to meet healthy behavior, “personal responsibility,” and work requirements in order to access certain benefits. In January 2020, CMS approved Texas’ request to restrict enrollees’ free choice of provider for family planning services, a request that CMS had denied under the Obama administration. A few other states have pending waivers that would restrict enrollees’ free choice of provider for family planning services.

The Trump administration has not approved several other eligibility and benefit waiver provisions. CMS has declined to approve authority to impose lifetime limits on Medicaid benefits for eligible beneficiaries (KS);24 condition coverage on drug screening, and if indicated, testing and treatment (WI); and to require stricter verification of U.S. citizenship and state residency than already required under federal law (NH).

As of October 2020, CMS is also considering requests to expand coverage for pregnant and postpartum women. These include requests that would maintain higher eligibility levels (above 138% FPL) for postpartum women in expansion states. Pending waivers include requests to expand eligibility to six (NJ) or twelve months (IL) postpartum, compared to the 60 days available under current law. Additional states have reported plans to apply for waivers that will expand postpartum coverage (GA and IN). In September 2020, the United States House of Representatives passed a bill that would allow states to extend postpartum Medicaid coverage to 12 months via a state plan option rather than through the waiver process.

Financing Changes

Some states have proposed waivers to make significant Medicaid financing changes, though none has been approved to date. These waivers include Utah’s request for a per capita cap funding structure — which remains formally pending at CMS, although the state has moved forward with full expansion — and Tennessee’s request for a modified block grant, which is pending at CMS. Several states25 (AR, GA, MA, UT) have submitted waiver requests seeking to limit ACA expansion eligibility by setting the income limit at 100% instead of 138% FPL or capping enrollment while still receiving the enhanced ACA federal matching rate, though none have been approved.26 Both the Obama27 and Trump28 administrations have issued policy guidance (although with different rationales) indicating that states cannot receive the enhanced federal matching rate unless they cover all newly eligible adults up to 138% FPL. CMS reiterated this policy in its HAO guidance but invited other limits on coverage (some of which have not been approved under other waivers to date) that would be permissible in an HAO demonstration under the regular matching rate (discussed below).

CMS published guidance on January 30, 2020, that introduced the option for states to pursue “Healthy Adult Opportunity” (HAO) demonstrations. The guidance would allow states “extensive flexibility” to use Medicaid funds to cover ACA expansion adults and nonelderly adults covered at state option who do not qualify on the basis of disability, without being bound by many federal standards related to Medicaid eligibility, benefits, delivery systems, and program oversight. In exchange, states would agree to an annual limit on federal financing in the form of a per capita or aggregate cap. States that opt for the aggregate cap and meet performance standards could access a portion of federal savings if they keep actual spending under the cap. In May 2020, Oklahoma submitted an 1115 request pursuing an HAO demonstration with a work requirement and other eligibility and benefit restrictions that would apply to a new expansion adult population; however, the state withdrew this application in August 2020 following a successful ballot measure adopting a traditional Medicaid expansion in June 2020. No other state has indicated pursuit of an HAO demonstration to date, and any such waivers are likely to face litigation if approved. State interest in pursuing Medicaid financing changes that could shift fiscal risk to states such as the HAO option has been limited to date and is not expected to increase, given that the pandemic and economic downturn has resulted in increased Medicaid enrollment, adverse state budgetary impacts, and uncertainty about the future.

The HAO demonstrations would allow states to not apply some provisions of federal law, consistent with earlier CMS approvals, as well as other provisions that CMS has not previously approved. The “menu” of provisions that CMS offers under HAO demonstrations includes those not approved by the current administration in previous state Section 1115 waiver requests (e.g., asset tests for populations whose financial eligibility is based on modified adjusted gross income, more frequent eligibility redeterminations, elimination of hospital presumptive eligibility, and closed prescription drug formularies).29 In June 2018, CMS rejected Massachusetts’ request to adopt a closed prescription drug formulary.30

Behavioral Health

States are using Section 1115 waivers to authorize Medicaid payment for substance use disorder (SUD), and, more recently, mental health treatment services, in “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs).31 While most recent activity involves states seeking IMD waivers, a few states are pursuing community-based behavioral health benefit expansions, targeted behavioral health eligibility expansions, or behavioral health delivery system reform. On November 1, 2017, CMS issued a state Medicaid director letter that revised guidance that the Obama administration issued in July 2015.32 The revised guidance continues to allow CMS to approve IMD payment waivers for SUD33 but makes other changes; for example, waivers under the 2015 guidance were contingent on states covering community-based SUD treatment services at the time of approval, while the 2017 guidance allows states up to two years after waiver approval to cover “critical levels of care.” As of October 2020, CMS has approved 28 IMD SUD waivers. Some of these waivers include community-based benefit expansions in conjunction with an IMD waiver.34

On November 13, 2018, CMS issued guidance inviting states to apply for Section 1115 waivers authorizing federal Medicaid payment for mental health services provided to people in IMDs. These includes services for adults with a serious mental illness (SMI) or for children with a serious emotional disturbance (SED). This guidance reverses prior CMS policy not to use Section 1115 waiver authority to allow Medicaid payments for IMD services for non-elderly adults with a primary mental health diagnosis and could have implications for states’ community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act and the Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead decision.35 In December 2019, CMS approved the first waiver (DC) to cover treatment of SMI and/or SED in an IMD under the November 2018 guidance. CMS also reapproved Vermont’s existing IMD mental health waiver in December 2019 under the new guidance and approved similar waivers for Indiana in January 2020 and for Idaho in April 2020. CMS has noted that states may participate in the SUD demonstration and the SMI/SED demonstration at the same time.

Delivery System Reform

In a shift from some of the Obama administration’s Section 1115 waiver initiatives, demonstrations designed to promote payment and delivery system reforms have not been a key priority of the Trump administration. For example, the Obama administration approved a number of Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) waivers, which provided states with significant federal funding to support hospitals and other providers in changing how they provide care to Medicaid beneficiaries.36 Although DSRIP funding was never intended to be permanent, the current administration has reduced funding for DSRIP renewals37 and not approved new demonstrations.38 Several states have used DSRIP demonstrations to address social determinants of health, although these demonstrations have not included federal funding to pay directly for non-medical services that target such needs. One exception is North Carolina’s “Healthy Opportunity Pilots” Section 1115 waiver, which CMS approved in October 2018. The demonstration authorizes $650 million in Medicaid funding over five years for a new pilot program to cover evidence-based non-medical services that address specific social needs (e.g., housing instability, food insecurity) linked to health/health outcomes. These services would be available for certain high-risk enrollees who meet physical or behavioral health and social risk factor criteria. Interested states are watching North Carolina’s implementation; however, the state has temporarily suspended these pilots due to the COVID-19 pandemic and CMS has not released formal guidance in this area or signaled that it will approve similar waivers. Finally, while the post-ACA Obama administration39 was phasing down uncompensated care/low income pool funding because states could now obtain federal financing for covering expansion adults (which would lower state uncompensated care burdens), the Trump administration has shown willingness to continue such waivers. Although CMS did not approve requests for uncompensated care pool increases in New Mexico and Kansas in 2019,40 the agency approved increases in such funding in two non-expansion states, Texas41 and Florida,42 ,43 in December 2017.

What to Watch in Waivers Looking Forward

The future of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated economic downturn may impact the waiver landscape. Waiver submission activity slowed in the face of the pandemic as states faced increased Medicaid enrollment, adverse economic and state budgetary impacts, and uncertainty about the future. Further, the COVID-19 PHE has both limited state options to enforce new eligibility and enrollment restrictions (as states receive enhanced federal matching funds and meet MOE conditions) as well as resulted in states not enforcing existing restrictions in order to facilitate access to coverage and services during the pandemic. The future course of the pandemic as well as the duration of the PHE declaration and economic downturn may affect state decisions to pursue future Section 1115 waivers. Although CMS released a new emergency COVID-19 Section 1115 demonstration in March 2020, only eight states have received approvals to address the pandemic using these waivers, with most approvals to date limited to provisions in the template. These waivers will expire 60 days after the PHE’s current end date of January 21, 2021 unless HHS renews the PHE.

Under either a potential Biden or Trump administration, the Supreme Court’s decision on the future of the ACA will have far-reaching consequences that may impact Section 1115 waivers. Medicaid expansion could be eliminated if the Court overturns the entire ACA, which could impact state adoptions of Medicaid expansion with modifications through Section 1115 waivers. In this circumstance, both authority under federal law to cover expansion adults as well as the enhanced federal funding for this coverage would cease, requiring states to find savings elsewhere to finance this coverage. Many approved and pending waiver provisions modify Medicaid program requirements for expansion populations, such as imposing work requirements, charging premiums, and restricting benefits. These waivers could also be affected by the outcome of the Court’s ACA decision.

Looking forward, the future landscape of Section 1115 waivers also depends on the outcome of the November 2020 presidential election. Waivers generally reflect priorities identified not only by states but also by CMS (a federal agency within HHS administered by presidential appointees) and thus often reflect changing priorities from one administration to another.

- Under a second Trump administration, current priorities would presumably continue and the future of work requirement and financing changes would likely lie with the courts. The Trump administration is seeking Supreme Court review of two DC Circuit Court of Appeals decisions that found the Secretary’s work requirement waiver approvals in Arkansas and New Hampshire were unlawful. If Trump is reelected in November 2020, the future of Medicaid work requirements—as well as other administration priorities that could face legal challenges, such as HAO capped financing proposals—likely lies with the courts. After the expiration of the COVID-19 PHE and associated MOE requirements, a second Trump administration may also re-focus on additional waivers restricting eligibility, enrollment, and/or benefits.

- If former Vice President Joe Biden is elected, his administration would have the authority to rescind existing guidance and/or issue new guidance. Former Vice President Joe Biden is supportive of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and has proposed using a federal public option to cover low-income Americans in states that have not expanded. While Biden’s formal campaign proposals are silent on Medicaid waivers, he has critiqued work requirements and pledged not to “undermine Medicaid.”44 A potential Biden administration could potentially rescind work requirement and other guidance and/or issue new guidance. CMS also generally reserves the right to withdraw waiver and/or expenditure authorities at any time and could do so under a potential Biden administration, in which case states would have the opportunity to request a hearing to challenge CMS’s determination. Additionally, as Section 1115 demonstrations expire, a potential Biden administration would have opportunities to decline to renew or to renegotiate those waivers. Biden’s campaign has indicated that, if elected, his administration would provide federal support for state Medicaid programs during the COVID-19 economic crisis, which could also include approvals of more expansive emergency waivers to aid state responses to the pandemic during the PHE.

Appendices

Appendix A

How Have States Used Section 1115 Demonstration Waivers in the Past?

From Medicaid’s beginning in 1965 through the early 1990s, waivers were small in scope. Beginning in the 1990s, there was an increase in waiver activity, and waivers became broader in scope. General periods of waiver activity prior to the Trump administration are discussed below:

Broad Expansion Waivers (Mid-1990s-2001). In the pre-ACA mid-90s through the early part of the 2000s (before statutory authority/federal funds were directly authorized for coverage expansion to childless adults under the ACA), most waivers focused on expanding coverage. Many began as state efforts to implement broader managed care delivery systems than were then permitted under federal law. States used savings from mandatory managed care or redirected disproportionate share hospital funds to offset expansion costs, and flush economic times during the mid- to late-90s helped support expansion efforts. Two of the largest waivers approved during this time (OregonHealth Plan and TennCare) also restructured coverage for existing beneficiaries in ways that were considered very controversial at the time.

HIFA and Other Waivers (2001 Forward). In August 2001, under President Bush, the administration announced the Health Insurance Flexibility and Accountability (HIFA) waiver initiative, which promoted the use of waivers to expand coverage within “current-level” resources and offered states increased flexibility to reduce benefits and charge cost-sharing to offset expansion costs. However, states had limited interest and success in expanding coverage under HIFA, and waivers instead began to increasingly focus on cost control as the nation moved into an economic downturn. Expansions that did move forward under HIFA waivers were generally limited, particularly when compared to the larger expansions of the 1990s. Beginning in 2005, waivers were approved in Rhode Island and Vermont set global caps on federal funds. Also during this same period, Massachusetts obtained a waiver that provided support for its efforts to provide universal coverage without significantly restructuring its Medicaid program.

Pre-ACA Expansion Waivers (2010-2013). Six states (CA, CO, DC, MN, NJ, and WA) used waivers to expand Medicaid coverage to adults after the enactment of the ACA to prepare for 2014.

Emergency Waivers (periodic over time in response to emergencies). Beyond these themes, waivers have also helped states quickly provide Medicaid support during emergencies, for example, by enabling a vastly streamlined enrollment process in New York in the wake of the September 11th attacks, and by assisting states in providing temporary Medicaid coverage to certain groups of Hurricane Katrina survivors and those affected by lead contaminated water in Flint, Michigan.

Appendix B

What are the CMS Criteria for Approving Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers?

In response to criticism from the General Accounting Office (GAO) about the lack of standards used to determine whether proposed Section 1115 demonstrations further Medicaid program objectives, CMS under the Obama administration posted a set of criteria to use when considering waiver requests in 2015. The Trump administration revised these criteria in November 2017. For comparison, both sets of criteria are listed below.

2015 CMS Waiver Approval Criteria

- Increase and strengthen overall coverage of low-income individuals in the state;

- Increase access to, stabilize and strengthen providers and provider networks available to serve Medicaid and low-income populations in the state;

- Improve health outcomes for Medicaid and other low-income populations in the state; or

- Increase the efficiency and quality of care for Medicaid and other low-income populations through invitations to transform service delivery networks.

November 2017 Revised CMS Waiver Approval Criteria

- Improve access to high-quality, person-centered services that produce positive health outcomes for individuals;

- Promote efficiencies that ensure Medicaid’s sustainability for beneficiaries over the long term;

- Support coordinated strategies to address certain health determinants that promote upward mobility, greater independence, and improved quality of life among individuals;

- Strengthen beneficiary engagement in their personal healthcare plan, including incentive structures that promote responsible decision-making;

- Enhance alignment between Medicaid policies and commercial health insurance products to facilitate smoother beneficiary transition; and

- Advance innovative delivery system and payment models to strengthen provider network capacity and drive greater value for Medicaid.

Endnotes

- Major areas of focus of current approved state Section 1115 waivers include: financing changes; eligibility and enrollment restrictions; work requirements; benefit restrictions, copays and healthy behaviors; behavioral health; delivery system reform initiatives; authorization of the delivery of Medicaid long-term services and supports (LTSS) through capitated managed care; and other targeted eligibility changes. ↩︎

- 42 U.S.C. § 1315. ↩︎

- Some states have multiple waivers, and many waivers are comprehensive and may fall into a few different areas. ↩︎

- The Secretary’s waiver authority is limited to the provisions of 42 U.S.C. § 1396a, provided that waivers are demonstration projects that further Medicaid program objectives. 42 U.S.C. § 1315. ↩︎

- In August 2018, CMS issued guidance related to Section 1115 budget neutrality, which outlined methodology adjustments to calculating “without waiver” expenditures that would be fully phased in for waiver extensions beginning January 1, 2021. Notably, these methodology changes restrict the ability of states with long-running demonstrations to roll over “unspent” budget neutrality savings and to extend baseline spending assumptions for years without adjustment. SMD # 18-009, Budget Neutrality Policies for Section 1115 (a) Demonstration Projects, https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/downloads/SMD18009.pdf. ↩︎

- Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, The New Review and Approval Process Rule for Section 1115 Medicaid and CHIP Demonstration Waivers, (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, March 2012), http://kff.org/health-reform/fact-sheet/the-new-review-and-approvalprocess-rule/. ↩︎

- However, Indiana filed an amendment to its pending extension on May 25, 2017 and Kentucky filed an amendment to its pending application on July 3, 2017. Neither state held a state-level public comment period before submission to CMS. Although the final regulations involving public notice do not require a state-level public comment period for amendments to existing/ongoing demonstrations, CMS has historically applied these regulations to amendments. However, these amendments were not to ongoing demonstrations but to a new waiver request (KY) and extension request (IN). ↩︎

- However, CMS relieved Montana from the requirement to evaluate its expansion waiver based on its participation in a cross-state federal evaluation. ↩︎

- Robin Rudowitz, MaryBeth Musumeci, and Alexandra Gates, Medicaid Expansion Waivers: What Will We Learn? (Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, March 2016), http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/medicaid-expansion-waivers-what-will-we-learn/. ↩︎

- The November 6, 2017 CMCS Information Bulletin (found at: https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib110617-2.pdf) on Section 1115 demonstration process improvements also signaled CMS’s interest in moving toward reducing the frequency of reporting required for states to semi-annually or annually for certain demonstrations. ↩︎

- “About Section 1115 Demonstrations,” CMS, last accessed October 23, 2020, https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demo/about-1115/index.html. ↩︎

- This CMCS Information Bulletin also outlines changes to the “fast track” federal review process for Section 1115 waiver extension requests, removing the requirement that states must have at least one full extension cycle without “substantial program changes” before they are eligible to be considered for the “fast track” review process. (The “fast track” process was designed to expedite the federal review of certain Section 1115 waiver extensions requests that meet specified criteria.) ↩︎

- This approved waiver renewal for Indiana also includes a five-year extension of its SUD and SMI demonstrations as well as the waiver’s work requirements, disenrollment and lock-out period for non-payment of premiums, and lock-out period for failure to timely renew eligibility (conditional on the outcome of litigation that would allow these requirements to go forward). ↩︎

- State applications for emergency COVID-19 Section 1115 waivers may have included requests for provisions that CMS approved under other emergency authorities. ↩︎

- Washington had proposed using Medicaid funds to provide additional subsidies for people enrolled in Qualified Health Plans (QHPs) with income at or below 200% FPL to allow individuals to purchase and use Marketplace coverage with no or low out-of-pocket costs. ↩︎

- Letter from Arizona Medicaid Director to CMS (Oct. 17, 2019), https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/az/Health-Care-Cost-Containment-System/az-hccc-postponement-ltr-ahcccs-works-10172019.pdf. ↩︎

- While Indiana began work requirement implementation in 2019, no hours were required in the first 6 months. The phase-in of required hours begins in months 7-9 with a requirement of 5 hours per week. On October 31, 2019, the Indiana Family and Social Services Administration announced that it would temporarily suspend the enforcement of its work requirement, which was scheduled to begin January 2020, due to a pending legal challenge. The state noted that it was delaying benefits suspensions pending the outcome of the state’s work requirement legal challenge. ↩︎

- Utah Department of Health, “Community Engagement Requirement Suspended,” https://medicaid.utah.gov/expansion/community-engagement-requirement-suspended/ ↩︎

- South Carolina’s work requirement applies to traditional parent/caretaker relative enrollees up to 100% FPL, Transitional Medical Assistance enrollees, and a newly established Targeted Adult Group. The Targeted Adult Group includes certain childless adults experiencing homelessness, justice system involvement, and/or need for SUD treatment; a limited number of pregnant or postpartum women up to 194% FPL with SUD and/or serious mental illness; and a limited number of parents who have children in foster care, earn up to 138% FPL, are undergoing SUD treatment, and have not had their parental rights terminated. ↩︎

- Georgia’s work requirement applies to adults up to 100% FPL who are not otherwise eligible for Medicaid coverage: parent/caretaker relative enrollees 35-100% FPL and childless adult enrollees 0-100% FPL. ↩︎

- Nebraska’s work requirement applies to expansion beneficiaries (up to 138% FPL) who do not meet any exemptions. Non-participation in this work requirement does not affect overall Medicaid eligibility, but does limit access to covered benefits. ↩︎

- Waiver provisions in some states may be approved but not implemented. ↩︎

- In October 2017, CMS approved an amendment to Iowa’s waiver eliminating 3-month retroactive coverage for nearly all new Medicaid applicants. The retroactive coverage waiver applies to all other state plan populations, including low-income parents, children over age 1, ACA expansion adults, seniors, and people with disabilities. Pregnant women and infants under age 1 still qualify for retroactive coverage in Iowa. In 2018, the state restored retroactive coverage for nursing facility residents. CMS also approved retroactive coverage waivers in Florida (November 2018), New Mexico (December 2018), and Arizona (January 2019) which apply to waiver populations including seniors and people with disabilities. In June 2019, NM (under its new governor) submitted an amendment to CMS requesting to reinstate the full 90-day retroactive coverage period for all affected individuals. CMS approved the amendment request on February 7, 2020. ↩︎

- In a CMS administrator letter to Kansas on May 7, 2018, CMS rejected Kansas’ proposal to impose a lifetime limit on Medicaid benefits for eligible beneficiaries. ↩︎

- The Trump administration rejected Massachusetts’ request for partial expansion to 100% of the FPL using the ACA enhanced match on June 27, 2018. The current administration did not make a decision on Arkansas’ partial expansion request in its March 5, 2018 approval of the Arkansas Works waiver amendment request. In an 8/16/2019 letter to Utah, CMS indicated that it would continue not to approve state requests for the ACA enhanced matching rate unless the states covered the entire adult expansion group. CMS noted in the letter that it also would not approve an enrollment cap on the expansion population, as such a cap “would be tantamount to ‘partial expansion.’” In its January 2020 HAO guidance, CMS noted that states can continue to receive enhanced matching funds for ACA expansion adults only if they cover the full expansion population (all adults up to 138% FPL) without an asset test. Most recently, in October 2020, the administration declined to approve Georgia’s request for the ACA enhanced match rate for its expansion of Medicaid coverage to 100% FPL (with initial and continued enrollment conditioned on compliance with work and premium requirements), again emphasizing it would continue its policy of only providing this match for states that cover the full expansion population. ↩︎

- Utah’s existing Section 1115 waiver was first approved in 2002 and included a pre-ACA coverage expansion (called the Primary Care Network, PCN) to parents 60%-100% FPL and childless adults up to 100% FPL, at the regular matching rate. The PCN coverage expansion provided a limited benefit package of primary and preventive services to a capped number of these adults and was funded by reduced benefits for traditional low-income parents. In March 2019, a waiver amendment moved Utah’s PCN adults to its “Adult Expansion Population.” In December 2019, Utah adopted the full ACA expansion and is now receiving the enhanced ACA matching rate for its expansion population. Still, while expansion adults receive full state plan benefits if they are childless or fall into the state’s Targeted Adult group, expansion parents receive a more limited benefit package than one designed to meet the alternative benefit package requirements for expansion adults under the ACA. ↩︎

- The Obama administration issued policy guidance, consistent with its legal interpretation of the ACA, indicating that states cannot receive enhanced federal ACA expansion funding unless they cover all newly eligible adults through 138% FPL. ↩︎

- In an 8/16/2019 letter to Utah, CMS indicated that it would continue not to approve state requests for the ACA enhanced matching rate unless the states cover the entire adult expansion group. ↩︎

- Maine and New Hampshire requested authority to impose asset tests for poverty-related pathways, and Maine and Utah requested approval to waive hospital presumptive eligibility. Arizona proposed to redetermine eligibility every 6 months for all expansion enrollees and every 3 months for individuals who have a change in circumstance that results in non-compliance with waiver requirements. ↩︎

- In its rejection, CMS noted that it would only be willing to consider a closed formulary proposal under which the state agrees to negotiate directly with manufacturers and forgo all manufacturer rebates available under the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program. ↩︎

- The federal Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act creates a state plan option, from October 2019 through September 2023, for states to receive federal Medicaid payments for non-elderly adults with SUD in an IMD up to 30 days per year. ↩︎

- The revised guidance requires certain demonstration components, such as residential treatment provider qualifications and capacity, opioid prescribing guidelines, access to naloxone, prescription drug monitoring programs, and care coordination between residential and community settings. States must report on core and state-specific quality measures, perform waiver evaluations, and be subject to a $5 million deferral per item for failure to comply with evaluation and reporting requirements. ↩︎

- Federal law generally bars states from receiving “any such [federal Medicaid] payments with respect to care or services for any individual who has not attained 65 years of age and who is a patient in an [IMD].” 42 U.S.C. § 1396d (a)(29)(B). ↩︎

- States also can offer a wide array of community-based behavioral health benefits under state plan authority. ↩︎

- Waiving the IMD payment exclusion and expanding institutional services without also ensuring adequate access to community-based services could have implications for states’ community integration obligations under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) if people with disabilities are inappropriately institutionalized. The Supreme Court’s 1999 Olmstead decision found that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities violates the ADA. The ADA’s community integration mandate is separate from federal Medicaid law. However, states rely on Medicaid funding to help meet their ADA obligations, because Medicaid is the primary payer for long-term services and supports, including home and community-based services. See https://modern.kff.org/medicaid/report/state-options-for-medicaid-coverage-of-inpatient-behavioral-health-services/. ↩︎

- Originally, DSRIP initiatives were more narrowly focused on funding for safety net hospitals and often grew out of negotiations between states and HHS over the appropriate way to finance hospital care. ↩︎

- In December 2017, CMS approved a five-year renewal of Texas’ Healthcare Transformation and Quality Improvement Program Section 1115 waiver. The waiver renewal decreases federal matching funds for the state’s DSRIP program between year one and year four, eliminating federal funding for DSRIP in the fifth year. New York requested a waiver amendment to continue its DSRIP program with additional funding. In a 2/21/2020 letter to New York, CMS noted that it was not approving the state’s requested extension of its DSRIP program. ↩︎

- Despite the Trump administration’s decreased focus on DSRIP waivers, in December 2019, Colorado submitted a waiver request for a new hospital-based DSRIP program (still pending at CMS). ↩︎

- Post-ACA Obama administration guidelines established that 1) uncompensated care pool funding should not pay for costs that would be covered in a Medicaid expansion, 2) Medicaid payments should support services provided to Medicaid beneficiaries and low-income uninsured individuals, and 3) provider payment should promote provider participation and access, and should support plans in managing and coordinating care. ↩︎

- On December 6, 2017, New Mexico requested five additional years of its uncompensated care pool with increasing funding, but CMS only approved one additional year. On December 20, 2017, Kansas requested an uncompensated care pool increase by $20 million per year, but CMS kept it at its current levels in a 1/15/2019 approval. ↩︎

- Texas Healthcare Transformation and Quality Improvement Program, Special Terms and Conditions, # 11-W-00278/6, approved January 1, 2018 through September 30, 2022, https://hhs.texas.gov/sites/default/files//documents/laws-regulations/policies-rules/1115-waiver/waiver-renewal/1115renewal-cmsletter.pdf. ↩︎

- Florida Managed Medical Assistance Program (MMA), Special Terms and Conditions, #11-W-00206/4, approved August 3, 2017, https://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Waivers/1115/downloads/fl/fl-medicaid-reform-ca.pdf. ↩︎

- Under Florida’s low income pool (LIP), funding was set at $1 billion in SFY 2016 and $608 million in SFY 2017. CMS indicated that the new LIP funding amount approved as part of the state’s extension request reflects “the most recent available data on hospitals’ charity care costs.” Florida’s LIP funds may be used for health care costs incurred by the state or by providers (hospitals, medical school physician practices, federally qualified health centers (FQHCs)/rural health centers (RHCs), and community behavioral health providers) to furnish uncompensated medical care for uninsured low-income individuals up to 200% FPL. ↩︎

- See Former Vice President’s Joe Biden’s remarks at Cherry Health in Michigan, March 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tO1CBDxRMus ↩︎