The KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor is an ongoing research project tracking the public’s attitudes and experiences with COVID-19 vaccinations. Using a combination of surveys and qualitative research, this project tracks the dynamic nature of public opinion as vaccine development and distribution unfold, including vaccine confidence and acceptance, information needs, trusted messengers and messages, as well as the public’s experiences with vaccination.

Key Findings

- As the U.S. continues to grapple with the “third wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor finds that more than seven in ten U.S. adults (72%) now report being at least partially vaccinated, with the surge in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to the Delta variant being the main motivator for the recently vaccinated and other factors like full FDA approval of the Pfizer vaccine and an increase in vaccine mandates playing a more minor role. The largest increases in vaccine uptake between July and September were among Hispanic adults and those ages 18-29, and similar shares of adults now report being vaccinated across racial and ethnic groups (71% of White adults, 70% of Black adults, and 73% of Hispanic adults). Large gaps in vaccine uptake remain by partisanship, education level, age, and health insurance status.

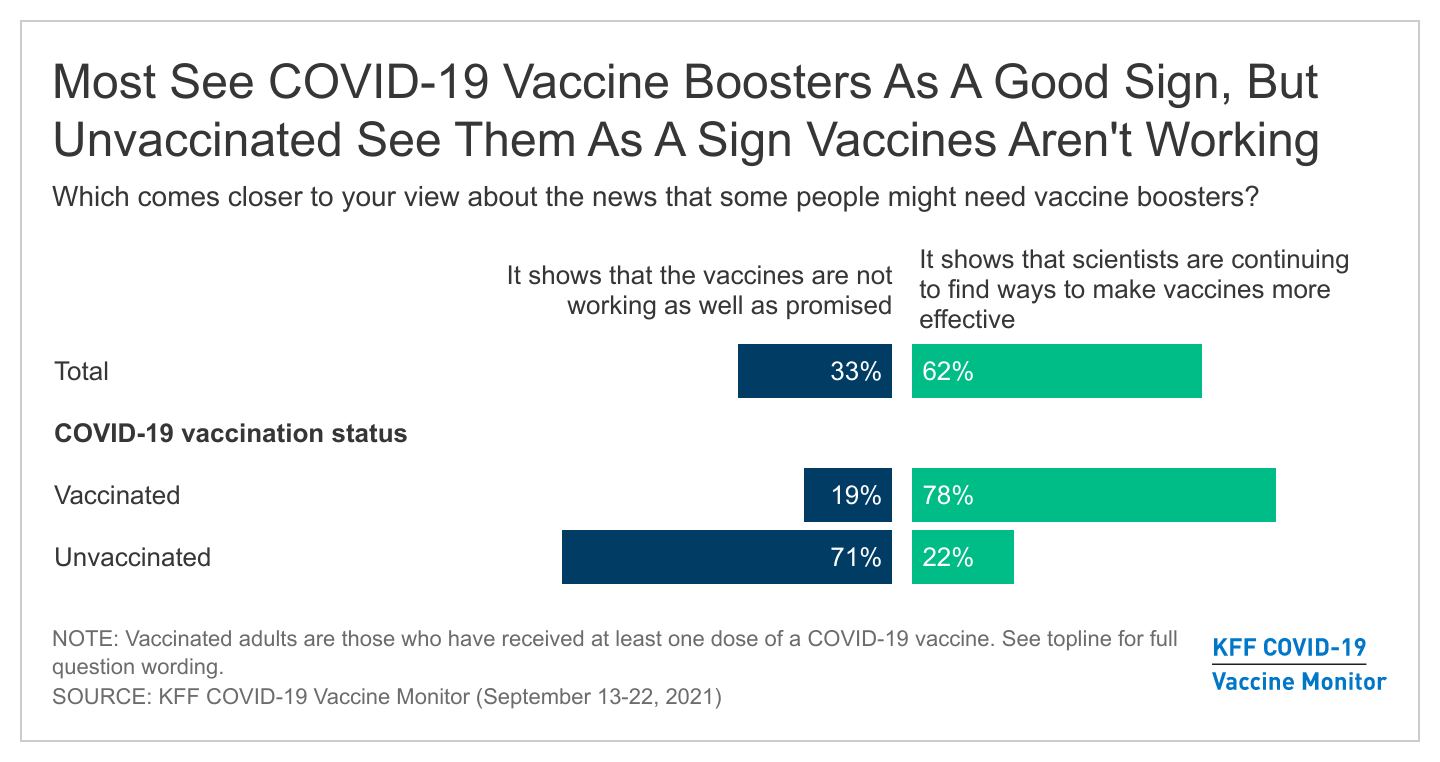

- With the FDA and CDC recently issuing recommendations related to COVID-19 booster shots, discussion of boosters appears to be a net positive for people who are already vaccinated, but a net negative for the unvaccinated. While a larger share of vaccinated adults say the information they have seen about boosters has been helpful (54%) than find it confusing (35%), among the unvaccinated almost twice as many find the information confusing as find it helpful (45% vs. 24%). Moreover, most unvaccinated adults see the booster discussion as a sign that the vaccines are not working as well as promised while most vaccinated adults see it as a sign that scientists are continuing to find ways to make vaccines more effective. Among fully vaccinated adults, a large majority say they would likely get a booster if the FDA and CDC recommended it for people like them, though vaccinated Republicans are somewhat less inclined than vaccinated Democrats.

- Amid a slew of recent announcements about COVID-19 vaccine requirements, majorities favor requirements for health care workers, school teachers, college students, and federal government employees, but the public is more divided on employer mandates in general and on K-12 schools requiring vaccines for eligible students. More specifically, nearly six in ten (58%) support the new federal government mandate on larger employers to require vaccines or weekly testing for their workers, and nearly eight in ten (78%) support the requirement that these employers offer paid time off for workers to get vaccinated and recover from side effects.

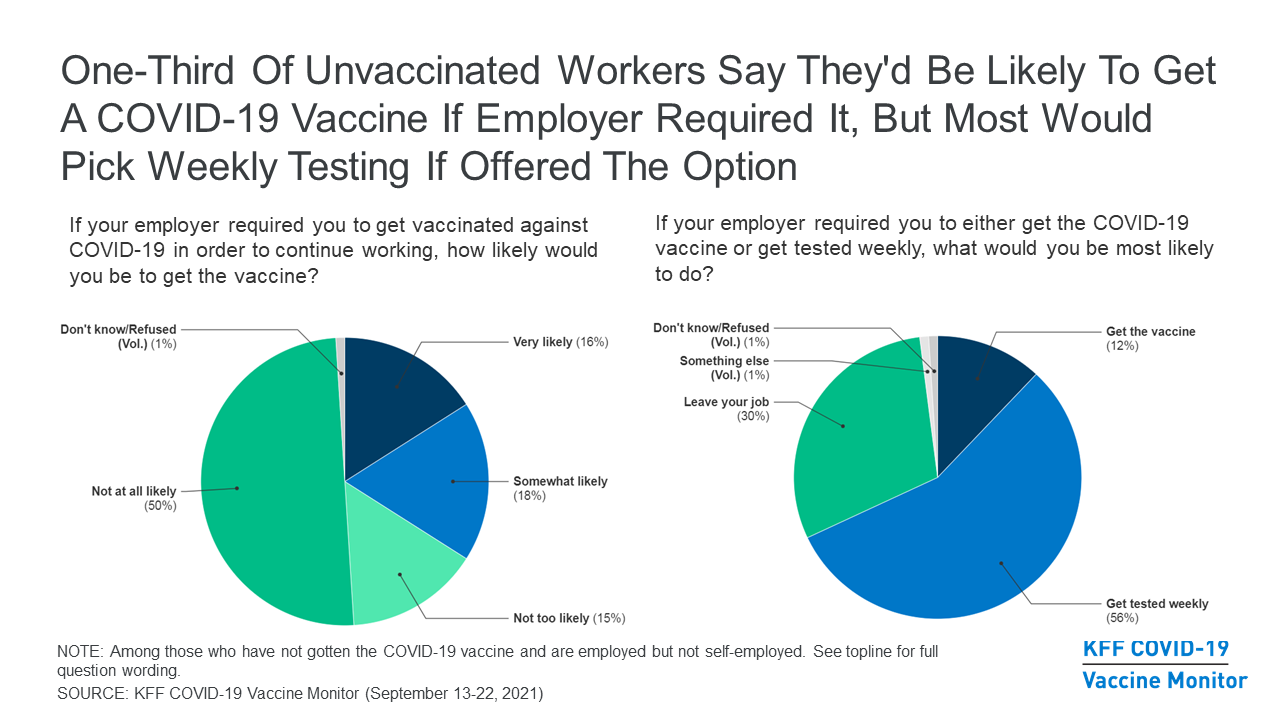

- Despite a lukewarm reception for employer COVID-19 vaccine mandates, such requirements do have the potential to further increase vaccine uptake somewhat. Asked what they would do if their employer required them to get vaccinated in order to continue working, about a third of unvaccinated workers say they would be likely to get vaccinated while two-thirds say they would be unlikely to do so (including half who say they would be “very” unlikely). However, when presented with the option to get vaccinated or face weekly testing (an option that larger employers could offer under the Biden plan), most unvaccinated workers (56%) say they would take the weekly testing option while just 12% say they’d get the shot and three in ten say they would leave their job.

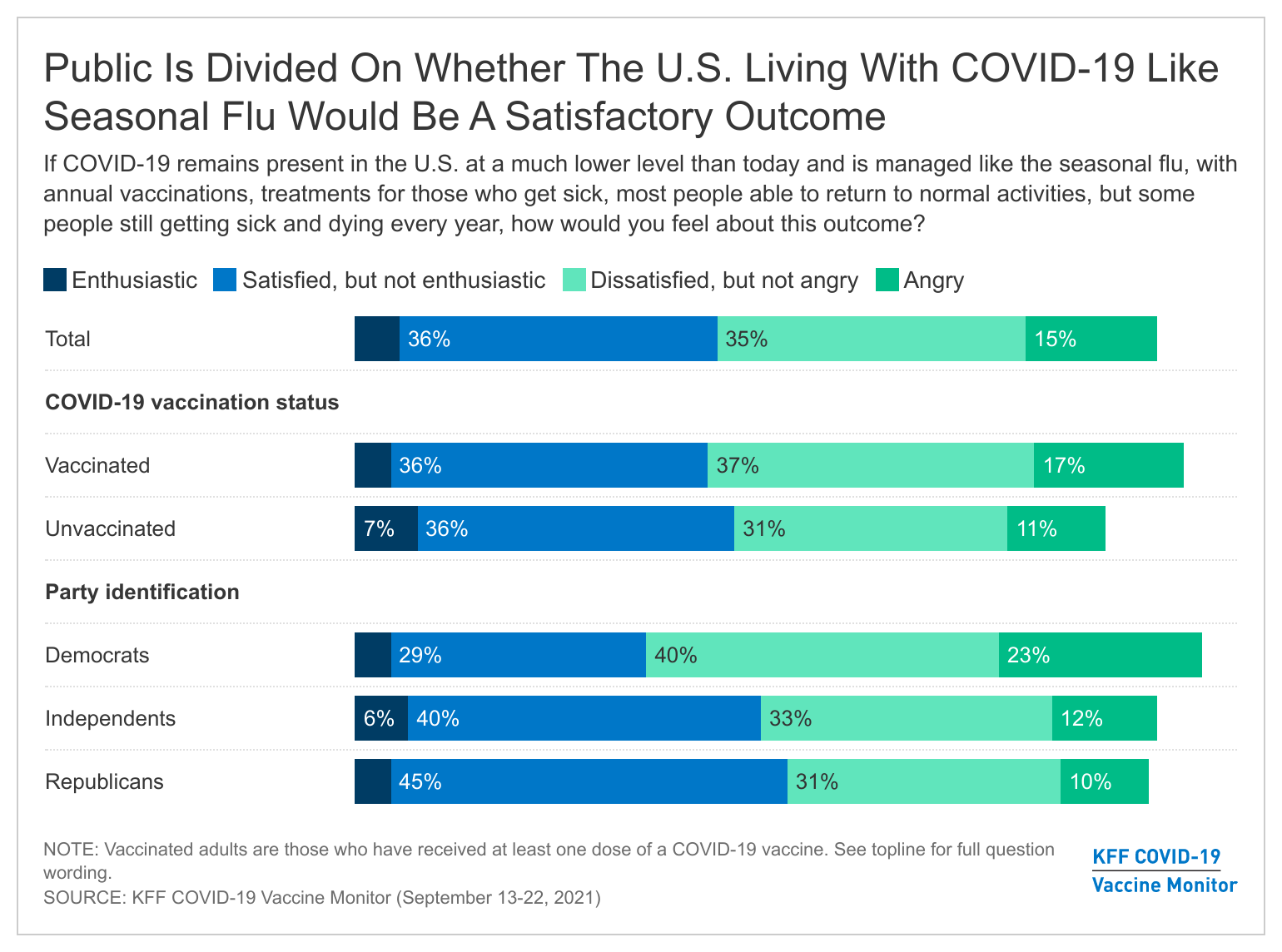

- The public appears resigned to a future in which COVID-19 remains present in the U.S. and is managed much like the seasonal flu rather than one in which the disease is completely eliminated. Eight in ten (79%) believe COVID-19 is something the U.S. will learn to live with, and while the public divides on whether they would be satisfied or dissatisfied with this outcome, few say they would feel either enthusiastic (5%) or angry (15%) if the disease remains present in the U.S. and is managed with vaccines and treatments like seasonal flu, with some people still getting sick and dying every year but most able to return to their normal activities.

- Partisanship and vaccination status continue to loom large as factors in how the public views both the U.S. vaccination effort and the government’s response to the pandemic in general. For example, while Democrats are most likely to see individuals refusing the COVID-19 vaccine and not taking enough precautions for the current surge in coronavirus cases, Republicans are most likely to view immigrants and tourists bringing the disease into the U.S. as a major reason for the surge. Similarly, the top reason vaccinated adults see driving high caseloads is vaccine refusal, while the unvaccinated say the main reason is that the vaccines aren’t working as well as promised. Some express anger as well, with two-thirds (65%) of Democrats and half (51%) of vaccinated adults saying the current state of the pandemic makes them angry at people who have not gotten a vaccine, and six in ten Republicans (59%) and a similar share of unvaccinated adults (56%) saying it makes them angry at the federal government.

- Looking ahead to the potential future political implications of the ongoing pandemic, Democrats retain a slight edge over Republicans when it comes to who voters see as having the better approach to handling the pandemic, but independents are divided with 32% preferring the Democratic Party’s approach, 27% preferring the Republican Party’s approach, and another 27% saying they prefer neither. Moreover, while most independent voters (61%) say the U.S. response to the pandemic hasn’t changed their intentions about which party’s candidates to support in future elections, 21% say it makes them more likely to support Republican candidates and 15% say it makes them more likely to support Democrats.

Trends In COVID-19 Vaccination Intentions And Uptake

In the midst of a “third wave” of the U.S. COVID-19 pandemic driven largely by the highly contagious Delta variant, more than seven in ten U.S. adults (72%) now report that they have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, up from 67% in July. An additional 2% say they plan to get the vaccine as soon as possible. The share who say they want to “wait and see” how the vaccine works for others before getting it themselves dropped to 7% in September. Four percent of adults this month say they will get vaccinated only if required for work, school, or other activities and 12% say they will “definitely not” get the vaccine.

The largest increases in self-reported COVID-19 vaccination rates between July and September were among younger adults (up 11 percentage points among 18-29 year-olds) and Hispanic adults (up 12 percentage points). The largest remaining gap in vaccination rates is by partisanship, with 90% of Democrats saying they have gotten at least one dose compared to 68% of independents and 58% of Republicans. In addition, large differences in self-reported vaccination rates remain between older and younger adults, between those with and without college degrees, and between those with higher and lower incomes, while rural adults continue to lag behind those living in urban and suburban areas. Non-elderly adults without health insurance also continue to report one of the lowest COVID-19 vaccination rates of any group (54%).

Similar shares of Hispanic (73%), Black (70%), and White (71%) adults now report having received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, a change from earlier in the vaccination effort when Black and Hispanic adults were much less likely to report being vaccinated than White adults, and reflecting other data showing that people of color make up a disproportionate share of recent vaccinations. KFF's analysis of state data on vaccination rates by race and ethnicity suggests that, when looking at people of all ages (including children who are not yet eligible to be vaccinated), White people continue to be vaccinated at higher rates than either Black or Hispanic people, although those gaps have narrowed over time.1

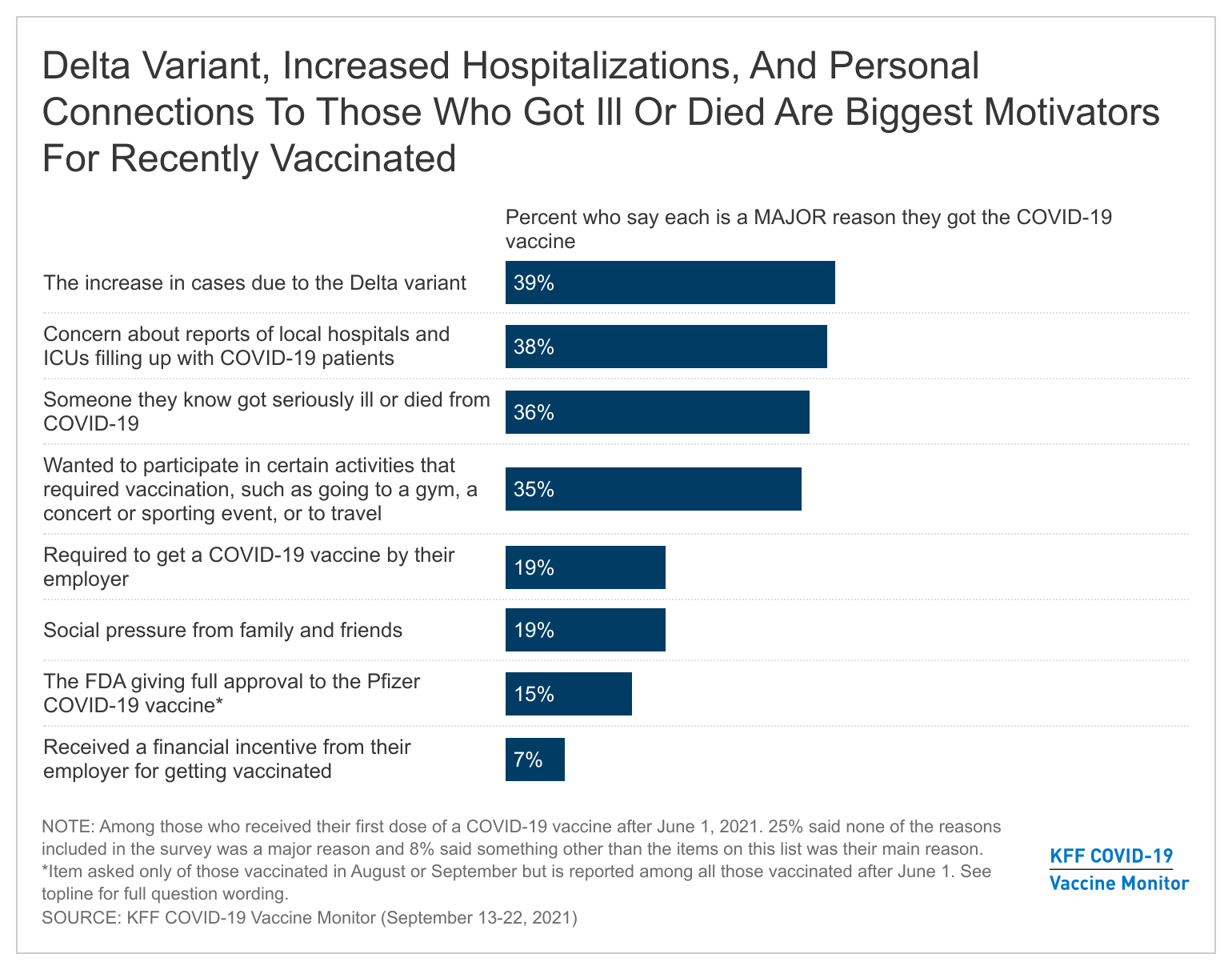

The latest KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor probed some potential reasons for getting vaccinated among those who received the vaccine more recently (since June 1) to understand the role of various factors in motivating the recently vaccinated, including the emergence of the Delta variant, the FDA giving full approval to the Pfizer vaccine, and an increase in vaccine mandates. We find that the rise of Delta and associated hospitalizations and deaths was the biggest motivating factor overall, while vaccine mandates and FDA approval played a more minor role.

More than one-third of those recently vaccinated say the increase in cases due to the Delta variant (39%), reports of local hospitals filling with COVID-19 patients (38%), and knowing someone who got seriously ill or died from the disease (36%) were major reasons they decided to get vaccinated. Altogether, 35% say one of these was the main reason they got vaccinated. Others were motivated by mandates of various sorts, including one-third (35%) who say a major reason for getting vaccinated was to participate in certain activities that required it such as traveling or attending events, and one in five (19%) who say a major reason was that their employer required it. Smaller shares choose such mandates as the main reason they got vaccinated (13% and 8%, respectively). Fifteen percent of those vaccinated since June2 say the FDA granting full approval to the Pfizer vaccine was a major factor in their decision, though just 2% of the recently vaccinated choose it as their main reason.

Among other reasons, 19% of the recently vaccinated say social pressure from family and friends was a major reason for getting vaccinated and 5% choose it as the main reason. Just 7% cite a financial incentive from their employer as a major reason and fewer than one percent choose it as the main reason.

Further supporting the idea that increased cases and deaths due to the Delta variant were a major motivating factor for the recently vaccinated, we find that among vaccinated adults, those living in counties with high COVID-19 caseloads and deaths are more likely to say they got their vaccine after June 1 compared to those living in counties with lower caseloads and deaths3 . While overall vaccination rates in counties with high case counts lag somewhat behind those in areas with lower case counts, 24% of vaccinated adults in high caseload counties say they received their first dose after June 1 compared to 15% in counties with lower case counts. Similarly, 23% of vaccinated adults in counties where the recent COVID-19 death rate is above the national average say they got their vaccine after June 1 compared to 14% of vaccinated adults in counties with the lowest recent death rates.

Boosters and Breakthrough Infections

In mid-August, the Biden Administration announced plans to begin rolling out COVID-19 booster doses to all Americans as early as September 20. More recently, the FDA instead authorized boosters of the Pfizer vaccine for older adults and certain high-risk individuals and a CDC panel issued similar recommendations.

The public’s attention to the conversation around COVID-19 vaccine boosters has increased since July, with about three-quarters (73%) now saying they’ve heard “a lot” or “some” about the possibility that booster doses may be necessary, up from six in ten in July. A slightly larger share of the public says the information they’ve seen about COVID-19 boosters has been helpful (45%) than the share who say it has been confusing (38%), but this varies greatly by vaccination status. Among those who are at least partially vaccinated, over half (54%) say the information they’ve seen has been helpful and about one-third (35%) say it has been confusing. Views are flipped among the unvaccinated, with almost half (45%) finding the information confusing, nearly twice the share who say it has been helpful (24%).

Among those who are fully vaccinated, a large majority say they will definitely (55%) or probably (26%) get a COVID-19 vaccine booster if the FDA and CDC recommend it for people like them, while small shares say they will probably not (8%) or definitely not get it (5%). Four percent of this group (3% of all adults) say they have already received a booster or additional vaccine dose. Notably, partisan differences in intentions to get a booster emerge even among the fully vaccinated population, with Democrats almost twice as likely as Republicans to say they’ll “definitely” get one if recommended (68% vs. 36%) and nearly a quarter (23%) of fully vaccinated Republicans saying they will probably or definitely not get a booster even if the FDA and CDC recommend it for people like them.

Among those who say they will probably or definitely not get a booster even if the FDA and CDC recommended it for people like them, reasons for not wanting a booster include feeling they won’t need it (14%), believing more research is necessary (13%), saying they have already been vaccinated (9%) and lack of trust in the government or the CDC (8%).

In their own words: What is the main reason why you would not get a booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine [if the FDA and CDC recommend it for vaccinated people like you]?

“Because they haven’t proved it as effective yet and if we really do need it or not.” – White man, age 54

“[I’m] confident [in the] first two doses.” – Hispanic man, age 21

“Because I got two first dose of the vaccine already and they definitely affected me and my health and there isn’t enough information about why I should get this booster shot.” – Black man, age 32

“Personal choice not enough evidence or study” – White woman, age 59

“More studies need to be done” – White woman, age 42

“I don’t trust anything the government says anymore.” – Black man, age 66

“I guess lack of trust in the government and the medical profession or I should say the CDC that part of it.” – White woman, age 68

Overall, the booster discussion seems to have increased rather than decreased the public’s confidence in the COVID-19 vaccines, though the opposite is true for those who remain unvaccinated. More than six in ten adults overall (62%) say the news that some people might need boosters “shows that scientists are continuing to find ways to make vaccines more effective” while one-third say it “shows that the vaccines are not working as well as promised.” Among those who are unvaccinated however, seven in ten (71%) say news about boosters is a sign that the vaccines aren’t working, including 69% of those in the “wait and see” group and 82% of those in the “definitely not” camp. Views on this topic also diverge by partisanship, with eight in ten Democrats (82%) seeing the booster discussion as a sign that scientists are continuing to find ways to make vaccines more effective and Republicans more evenly divided between this view (44%) and believing that boosters show the vaccines aren’t working well (52%).

Views of Breakthrough Infections

News about so-called “breakthrough” COVID-19 infections among some vaccinated people has also captured the public’s attention in recent weeks, with seven in ten U.S. adults saying they have heard “a lot” or “some” about these types of infections. Despite news about breakthrough infections, nearly seven in ten adults (68%), including majorities across partisan groups, say they agree more with the statement that “the fact that most vaccinated people who become infected with COVID-19 do not require hospitalization means that the vaccines are working” while about a quarter (26%) are more inclined to believe that “the fact that some vaccinated people are becoming infected with COVID-19 means that the vaccines are not working.”

However, as is the case with news about boosters, news of breakthrough infections plays more negatively among those who are currently unvaccinated, with two-thirds (66%, rising to 79% in the “definitely not” group) seeing breakthrough infections as a sign that the vaccines are not working.

Views on COVID-19 Vaccine Requirements

Vaccine Requirements For Work and School

In recent months, an increasing number of employers have announced COVID-19 vaccine requirements for their workers, many universities have begun to require vaccination for students, and some school districts are considering vaccine mandates for eligible students. In addition, on Sept 9, President Biden announced a COVID-19 action plan that includes a requirement for all federal government employees and contractors to be vaccinated as well as new requirements for employers with 100 or more employees.

The public remains somewhat divided on whether employers and others should require COVID-19 vaccination, with higher support for vaccine requirements in some settings and deep divisions along partisan lines. About six in ten say that vaccines should be required for health care workers (62%) and school teachers (58%), while slim majorities support mandates for federal government employees (55%), college and university students (55%), and state and local government employees (54%). The public is more divided on whether employers in general should require their workers to be vaccinated for COVID-19 (48% say they should and 50% say they should not). Similarly, as some school districts around the country have started to announce COVID-19 vaccination requirements for eligible students, about half the public says schools should do this (52%) and the other half says they should not (46%).

Not surprisingly, attitudes toward vaccine mandates differ greatly by partisan identification, with at least three in four Democrats saying COVID-19 vaccination should be required in each situation compared to around one-fifth to one-third of Republicans. Independents are divided on vaccine mandates in most settings, though a clear majority of independents (63%) says hospitals and other health care facilities should require their workers to be vaccinated.

Asked more specifically about the federal government requirement for larger employers to make sure their workers get vaccinated for COVID-19 or require unvaccinated workers to get tested at least weekly, a key element of President Biden’s plan announced on September 9, nearly six in ten (58%) support this requirement while about four in ten (39%) are opposed. An even larger majority (78%) support another element of the plan, the federal government requiring larger employers to give their workers paid time off to get a COVID-19 vaccine and recover from any side effects.

Partisans’ views differ on these new federal government requirements for employers, with the vast majority of Democrats in favor of both types of requirements. Among Republicans, a majority (58%) favor the requirement for employers to provide paid time off, but far fewer (29%) support the requirement to mandate vaccines or weekly testing while most (70%) are opposed. A large majority (77%) of independents supports the paid time off requirement, while independents are more divided on the worker vaccine mandate (53% support, 44% oppose).

Workers’ Experiences and Preferences

Among those who work for an employer (excluding the self-employed), 19% say their employer has already required them to get a COVID-19 vaccination, up from 9% in June. Half of all workers say they are not currently subject to an employer vaccine requirement and do not want their employer to require vaccination, while about three in ten (28%) are not currently required but want their employer to issue such a requirement. There are expected partisan divisions, with most workers who are Democrats saying they are already subject to an employer vaccine requirement or want their employer to issue one, and a large majority of Republicans (76%) as well as almost six in ten independents (56%) saying they don’t want their employer to require vaccination. Not surprisingly, the vast majority (87%) of unvaccinated workers are opposed to such a requirement, but as we found in our June survey, a substantial share (35%) of vaccinated workers are also opposed.

When unvaccinated workers are asked what they would do if their employer required them to get a COVID-19 vaccine in order to continue working, one-third (34%) say they’d be very or somewhat likely to get the vaccine, one in six (15%) say they would be “not too likely” to get it, and half (50%) say they would be “not at all likely” to get vaccinated. In a separate question that included an option for weekly testing, over half (56%) of unvaccinated workers say they would get tested weekly if presented with this option while 12% say they would get the vaccine and three in ten (30%) say they would leave their job.

Many workers continue to say they are not eligible for paid time off to get the COVID-19 vaccine and recover from side effects, or they are not sure if they are eligible. One-third (33%) of workers say their employer offers them paid time off to get a COVID-19 vaccine while three in ten say their employer does not offer this (31%) and 35% are unsure. Just over a third (35%) say they get paid time off to recover from vaccine side effects while 31% say they do not and 34% are unsure. The share of workers who report getting paid time off to get vaccinated or recover from side effects is lower among those with household incomes under $40,000 (23% and 28%, respectively) than it is among those earning at least $90,000 a year (37% and 44%), suggesting that increasing access to paid leave could help further reduce gaps in vaccination by age and income.

Views on State and Federal Laws Regarding Customer Vaccination Requirements

Similar to views on employer vaccine requirements, the public is divided and split on partisan lines when it comes to state and local laws regarding vaccine requirements for businesses. About half (49%) support states and local governments issuing COVID-19 vaccine requirements for indoor businesses like gyms, restaurants, and movie theaters, while the other half (49%) are opposed. About eight in ten Democrats (79%) support such laws while a similar share of Republicans (78%) are opposed. Among independents, a larger share opposes than supports such requirements (56% vs. 43%).

In recent months, some states and localities, including Florida, have issued orders that ban businesses from requiring their customers to show proof of COVID-19 vaccination. A slim majority (56%) of the public are opposed to these types of laws, while four in ten (41%) support them. Majorities of Democrats (69%) and independents (54%) oppose the bans, while Republicans are more evenly divided (47% support, 51% oppose).

School Mask Mandates

On another type of mandate question, a majority (56%) of the public says K-12 schools should require all staff and students to wear masks while at school and another 10% say schools should require masks for unvaccinated students and staff. About a third (31%) say schools should not have any mask mandate at all. As with other mandates, these views diverge by partisanship, with nearly all Democrats and six in ten independents supporting school mask requirements in some form and six in ten Republicans saying schools should not have any mask requirements at all.

The State Of The Pandemic, Government Response, And Political Implications

More than a year and a half since the start of the pandemic, most of the public expects COVID-19 will be something the U.S. will learn to live with and not something which will be eliminated. About eight in ten adults overall, and at least seven in ten across demographic groups, say they expect COVID-19 will “continue at a lower level and be something the U.S. will learn to live with and manage with medical treatments and vaccines, like the seasonal flu.” Few (14%) think COVID-19 will be “largely eliminated in the U.S. like polio.” Majorities of both vaccinated and unvaccinated adults see COVID-19 as something the U.S. will learn to live with and manage.

A majority of the public seem resigned to accept an outcome where COVID-19 remains present in the U.S. and is “managed like the seasonal flu, with annual vaccinations, treatments for those who get sick, most people able to return to normal activities, but some people still getting sick and dying every year.” About a third (36%) say they would be satisfied with this outcome, but not enthusiastic, a similar share (35%) say they would be dissatisfied with this outcome, but not angry. While a majority appear to be accepting of this possible outcome, one in six (15%) say they would be angry about this potential outcome, rising to a about one in four Democrats (23%).

Asked about various factors that might be contributing to the current surge of COVID-19 cases, majorities of adults say people not taking enough precautions, the infectiousness of the Delta variant, and too many people refusing to get vaccinated are major reasons for the current high case rate. However, there are notable differences between what vaccinated adults and unvaccinated adults see as major reasons.

The top factors vaccinated adults see as driving the high case levels are too many people refusing the vaccine (77%), people not taking enough precautions (73%), and the infectiousness of the Delta variant (67%). The top factor that unvaccinated adults see as driving current case counts is that “the vaccines are not as effective at preventing the spread of COVID-19 as scientists initially thought they would be” (58%), followed by immigrants and tourists bringing COVID-19 into the U.S. (40%), people not taking enough precautions (37%), and the infectiousness of the Delta variant (35%).

Unsurprisingly, there are some notable differences in what Democrats and Republicans say are the major reasons for the current high number of COVID-19 cases. Overwhelming majorities of Democrats say people not taking enough precautions like wearing masks and social distancing (89%), and too many people refusing to get the COVID-19 vaccine (87%) are major reasons for the current number high number of cases, whereas only about three in ten Republicans say the same. Large shares of Democrats also identify the infectiousness of the Delta variant (75%) and state and local governments being too quick to lift mask mandates and social distancing restrictions (73%) as major reasons why cases are so high, compared to fewer independents and Republicans who say the same. Notably, a majority of Republicans (55%) say immigrants and tourists bringing COVID-19 into the U.S. is a major reason for the high number of cases whereas fewer independents (34%) and Democrats (21%) see this as a major reason.

Despite a large share of the public seeing vaccine refusal as a major reason behind current high caseloads, a smaller share (38%) says the current state of the pandemic in the U.S. makes them feel “angry” at people who have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine. The same share (38%) say they feel angry at the federal government for the current state of the pandemic. Not surprisingly, these shares diverge along partisan lines and between those who have and have not gotten a COVID-19 vaccine themselves. Half of vaccinated adults (51%) say they are angry with those who have not gotten the COVID-19 vaccine compared to just 3% of unvaccinated adults. A majority of unvaccinated adults (56%) say they are angry with the federal government compared to three in ten of those who are vaccinated. Across partisans, about two-thirds of Democrats say they are angry with the unvaccinated while about six in ten Republicans say they are angry at the federal government. Among independents, a somewhat larger share says they are angry with the federal government (41%) than says they are angry with people who have not gotten vaccinated (33%).

For a large share of the public, the response to the pandemic has taken a toll on their trust in the federal government. Four in ten adults (42%) say the U.S. response to COVID-19 had decreased their trust in the federal government, while just 15% say it has increased their level of trust.

Across partisans, Democrats are more likely to say their trust in the federal government has increased (31%) than to say it has decreased (18%) though a plurality say the U.S. response has made no difference in their trust in the federal government. About two-thirds of Republicans (65%) say the U.S. response to the pandemic has decreased their trust in the federal government, as do almost half of independents (48%).

Despite a substantial share of the public expressing anger at the federal government for the current state of the pandemic, the Democratic Party retains a slight advantage over Republicans in voters’ trust to handle the pandemic going forward. Among registered voters, four in ten say the Democrats have the better approach to handling the pandemic while about a third (31%) prefer the Republican Party’s approach and 17% say they prefer neither. While about eight in ten partisan voters each prefer their own party’s approach, independents are divided with 32% preferring the Democrats’ approach, 27% preferring the Republicans’ approach, and about one in four (27%) saying they prefer neither party’s approach to handling the pandemic going forward.

Asked about the potential impact of the pandemic on future voting, about half of registered voters (49%) say the say the U.S. response to the pandemic hasn’t changed which party’s candidates they will support in future elections. One in four voters say the country’s response to the pandemic has made them more likely to support Democratic candidates while a similar share (23%) say it has made them more likely to support Republican candidates. Most independents (61%) say the U.S. response to the pandemic has made no difference in the likelihood of supporting a party’s candidates, while 21% say it makes them more likely to support Republican candidates and 15% say it makes them more likely to support Democrats.