As 2022 kicks off, a number of issues are at play that could affect coverage and financing under Medicaid, the primary program providing comprehensive health and long-term care coverage to low-income Americans. New COVID variants are surging and the fate of the Build Back Better Act (BBBA), a reconciliation bill that includes significant changes to health coverage and Medicaid, is hanging in the balance. In addition, Governors are poised to release proposed budgets amid continued uncertainty about the health and economic trajectory of the pandemic while the Biden Administration continues to use its authority to address the pandemic and to further strategic goals to expand coverage and access and to improve equity. Within this context, this issue brief examines key issues to watch in Medicaid in 2022.

Medicaid Coverage and Enrollment

Enrollment and the pandemic. Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, enrollment in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) grew to 83.2 million in June 2021, an increase of 12.0 million (16.8%) from February 2020. Enrollment growth reflects downturns in the economy due to the pandemic and provisions in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) that require states to ensure continuous coverage for current Medicaid enrollees to access a temporary increase in the Medicaid match rate during the Public Health Emergency (PHE) period, recently extended to April . Continuous enrollment has helped to preserve coverage and halted Medicaid churn, however, when these requirements end, states will begin processing redeterminations and renewals and millions of people could lose coverage if they are no longer eligible or face administrative barriers during the process despite remaining eligible. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has released guidance and strategies for states to help maintain coverage of eligible individuals after the end of continuous enrollment requirements. The BBBA also includes provisions that would phase-out the continuous enrollment requirement beginning April 1, 2022 with rules about disenrolling people tied to a phased down enhanced match rate. Within the parameters set by the Administration, or BBBA if enacted, states will largely be responsible for managing the unwinding of the continuous enrollment requirement, which could lead to variation in practices and in how many people are able to maintain coverage.

State decisions around Medicaid coverage. Beyond the pandemic and continuous enrollment requirements, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) included new coverage options for states. ARPA provides a two-year fiscal incentive to encourage states to newly adopt the Medicaid expansion. Over 2 million individuals living in the 12 states that have not adopted the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion fall into the coverage gap because they do not qualify for Medicaid and have incomes below poverty, making them ineligible for premium subsidies in the ACA Marketplace. A KFF analysis shows that all non-expansion states would see a net fiscal benefit from the ARPA incentive for two years if they adopt the expansion. The ARPA federal incentive reignited discussion around Medicaid expansion in a few non-expansion states during the last state legislative session, but no state newly voted to adopt the expansion. South Dakota will have a Medicaid expansion constitutional amendment on the November 2022 ballot. Six states have adopted the expansion by ballot initiative (Idaho, Maine, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Utah). ARPA also includes an option to allow states to extend postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months. Under current law, after the 60 days of postpartum coverage, individuals in states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion may continue to be eligible for Medicaid, but in non-expansion states many may become uninsured because Medicaid eligibility levels for parents are much lower than for pregnant people. The new option starts in April 2022 and as of last year, more than half of the states had taken steps to extend postpartum coverage.

BBBA and Medicaid coverage provisions. The version of the BBBA that passed the House would create a temporary pathway to coverage for people in the coverage gap by allowing them to purchase subsidized coverage (with no premiums and minimal cost sharing) in the ACA Marketplace starting in 2022 through 2025. To discourage states that have adopted the ACA Medicaid expansion from dropping that coverage, the BBBA would also increase the federal match rate for the expansion population in these states from 90% to 93% in 2023 through 2025. The CBO estimates that provisions to address the coverage gap would result in 1.7 million fewer uninsured people with a net federal cost of $57 billion over the next decade. In addition, the BBBA would require states to provide 12 months continuous coverage for postpartum people and children, which could help reduce churn among these populations. The BBBA would also partially lift the inmate exclusion (current policy that prohibits Medicaid from covering services provided during incarceration, except for inpatient services) by allowing federal Medicaid money to be used to pay for Medicaid-covered services 30 days prior to release for people who are incarcerated.

Administrative actions to maintain and expand coverage. In January 2021, the Biden Administration issued an Executive Order that called for efforts to “protect and strengthen Medicaid” and directed a review of waivers that may reduce coverage or undermine Medicaid. As part of that effort, the Administration issued final withdrawals of waivers, promoted under the Trump Administration, that conditioned Medicaid eligibility on work requirements. More recently, the Biden Administration took steps to withdraw or phase out waivers that included premiums in Medicaid. The Administration also approved some waivers to expand postpartum coverage and, in November 2021, issued a strategic vision for Medicaid and CHIP that includes expanding coverage and access as a key priority.

The Administration has also issued an Executive Order focused on streamlining eligibility and enrollment processes and increased efforts to reach uninsured individuals who are eligible for Medicaid or Marketplace coverage. In 2020, seven million uninsured people were eligible for Medicaid but not enrolled. Most of these individuals were adults and nearly two-thirds were people of color. For the 2022 Marketplace open enrollment period, the Biden Administration launched an expansive advertising and outreach campaign to educate consumers on the availability of both Marketplace and Medicaid coverage. It also increased funding for Navigators in the federal Marketplace seven-fold from $10 million in 2020 to $80 million in 2021. The enhanced Navigator funding will mean more staff to assist both Marketplace and Medicaid applicants.

What to Watch:

- What will happen to Medicaid enrollment when the continuous enrollment requirement ends? Will many people lose Medicaid coverage due to administrative barriers despite remaining eligible? Will people no longer eligible for Medicaid successfully transition to subsidized Marketplace coverage?

- If the BBBA passes, how will that affect Medicaid coverage and coverage options for those who are uninsured?

- If the BBBA is not enacted, will states use existing options and authority to expand Medicaid coverage?

Institutional and Home and Community Based Long-Term Care

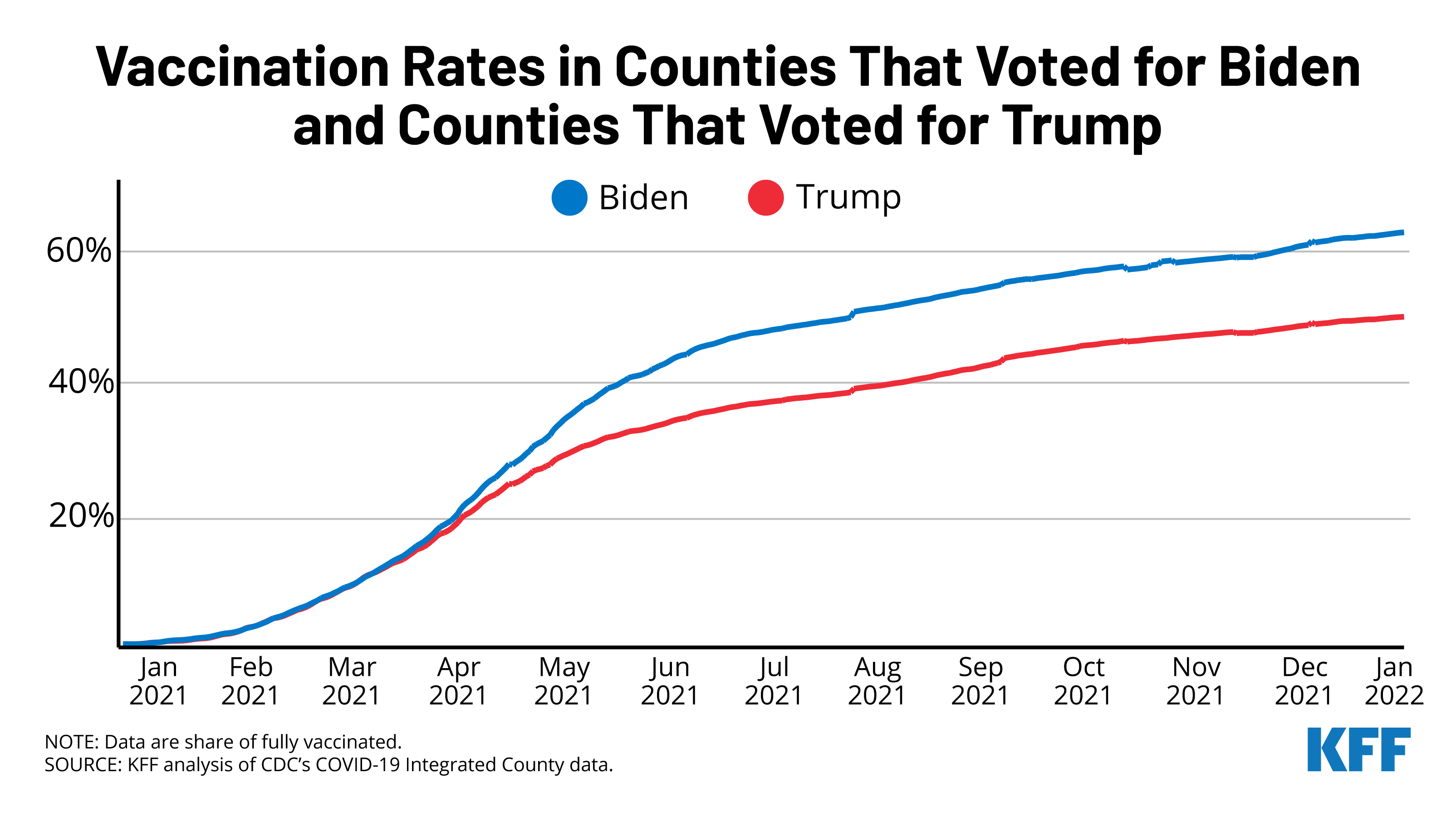

Staff and residents at long-term care facilities have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. In the first year of the pandemic, long-term care facilities accounted for 31% of all COVID-19 deaths in the US as of June 30, 2021. KFF analysis found that, following vaccine rollout in winter 2020-2021, weekly cases and deaths in long-term care facilities (including nursing homes, assisted living facilities, ICF/IIDs, and some congregate community-based settings) dropped, reaching an all-time low in June 2021, prior to new surges due to the Delta and most recently omicron variants. The pandemic has also affected the long-term care workforce. Unlike past recessions, the health sector saw a big drop in employment in early 2020, similar to other sectors as the COVID-19 pandemic shut down much of the nation’s economy and remains below expected employment levels through November 2021. Data show that the number of workers in nursing care and elder care facilities has continued to decline even after other health settings experienced a rebound. As of November, nursing care facilities and elder care facilities employed 15% and 11.1% fewer workers than they did in February 2020. The health and long-term care workforce could continue to be strained as some workers are vaccine hesitant and the new vaccine mandate for health care workers has been challenged in the federal courts. The Supreme Court recently allowed the rule to take effect while lawsuits proceed in 24 Republican-led states challenging it.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought new focus to the long-standing unmet need for home and community-based services (HCBS) among seniors and people with disabilities and direct care workforce shortages. The Medicaid HCBS provider infrastructure declined during the pandemic, with two-thirds of states responding to a KFF survey reporting a permanent closure of at least one provider. Additionally, important data gaps remain with just under half of responding states tracking COVID-19 vaccination rates among Medicaid HCBS enrollees. Recognizing Medicaid as the primary payer for HCBS, recent legislation has increased federal funding to support Medicaid HCBS. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) temporarily increases federal matching funds for Medicaid HCBS by an estimated $11.4 billion, and the BBBA passed by the House in November 2021 would provide $150 billion in new federal funds for Medicaid HCBS, including a permanent increase in the federal matching rate. The BBBA also includes new nursing facility staffing requirements, including a requirement to have a at least one registered nurse on duty 24 hours a day, seven days per week.

What to Watch:

- How will institutional and community based long-term care congregate settings continue to be impacted by the pandemic in terms of cases, deaths and staffing? How will providers and staff respond now that the Supreme Court has allowed CMS’s health care staff vaccine mandate to take effect, and how will litigation challenging the rule ultimately be resolved?

- Will states retain policies adopted under emergency authorities that expanded access to HCBS after the PHE ends?

- How will existing investments help states address the need to continue to expand access to HCBS?

- If BBBA passes, how will states use additional Medicaid HCBS funding to further expand eligibility and services and bolster the direct care workforce?

Access, Social Determinants of Health, and Health Equity

In response to the pandemic, states took action to increase the use of telehealth to expand access to care and also to increase the scope of coverage (and availability of telehealth) for behavioral health services. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many states expanded Medicaid telehealth coverage for a number of services and using multiple modalities (audio-visual and audio-only). Post-pandemic telehealth coverage and reimbursement policies are being evaluated in most states, with states weighing expanded access against quality concerns, especially for audio-only telehealth. In addition to telehealth, states continue to expand behavioral health services. Behavioral health conditions—including mental illnesses and substance use disorder (SUD)—are especially common among Medicaid enrollees and have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic. The proposed Build Back Better Act (BBBA) passed by the House of Representatives on November 19, 2021 would expand funding for HCBS and community mental health services. Also, CMS under the Biden Administration has identified behavioral health policy and investments as a key federal Medicaid priority.

In KFF’s 50-state budget survey, most states reported that the COVID-19 pandemic prompted them to expand Medicaid programs to address social determinants of health, especially related to housing supports. States also reported existing initiatives in this area in managed care organization (MCO) contracts (e.g., requirements for MCOs to screen and refer enrollees for social needs). Social determinants of health (SDOH) are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age that shape health. In response to the pandemic, federal legislation has been enacted to provide significant new funding to address the health and economic effects of the pandemic including direct support to address food and housing insecurity as well as stimulus payments to individuals, federal unemployment insurance payments, and expanded child tax credit payments. While measures like these have a direct impact in helping to address SDOH, health programs like Medicaid can also play a supporting role. Although federal Medicaid rules prohibit expenditures for most social needs, such as rent, state Medicaid programs have been developing strategies to identify and address enrollee social needs both within and outside of managed care.

The Administration and the majority of state Medicaid programs are implementing initiatives to address disparities in health care by race/ethnicity in Medicaid. Key state initiatives are focused on specific health outcomes including maternal and infant health, behavioral health, and COVID-19 outcomes and vaccination rates. In addition, the Administration issued a Request for Information to federal agencies to assess barriers and opportunities to advance equity for historically underserved individuals and communities. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated already existing health disparities for a broad range of populations, but specifically for people of color. Early analyses of available federal, state, and local data show that people of color were experiencing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases and deaths, but more recent data show racial disparities in cases and death rates have narrowed for Black and Hispanic people compared to earlier in the pandemic, while American Indian/Alaska Native people continue to experience higher rates of infection and death. In addition to worse health outcomes, data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey show that during the pandemic, Black and Hispanic adults have fared worse than White adults across nearly all measures of economic and food security.

State Medicaid agencies and Medicaid MCOS are implementing a variety of activities aimed at promoting the take-up of COVID-19 vaccinations. Given the large number of people covered by Medicaid, including groups disproportionately at risk of contracting COVID-19 as well as many individuals facing access challenges, state Medicaid programs and Medicaid MCOs (which enroll over two-thirds of all Medicaid beneficiaries) can help in COVID-19 vaccination efforts. MCOs are using member and provider incentives, member outreach and education, provider engagement, assistance with vaccination scheduling and transportation coordination, and partnerships with state and local organizations. Medicaid agencies are taking actions such as partnering with public health agencies, providing technical assistance to providers, and conducting outreach to facilitate vaccine take-up. States were also implementing policies to help facilitate access to vaccines for HCBS enrollees by partnering with public health agencies, using non-emergency transportation services and enlisting HCBS providers in outreach. More broadly, the BBBA would require state Medicaid programs to cover all approved vaccines recommended by Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and vaccine administration, without cost sharing, for adults (and receive a 1 percentage point FMAP increase for 8 quarters).

What to watch?

- How will states continue to leverage Medicaid to help address SDOH and racial equity and how will the Administration support these efforts through investments, guidance and demonstration waivers?

- How will Medicaid agencies continue to work with public health agencies, providers, managed care plans and enrollees to facilitate access to vaccines and boosters?