Many States Impose a Jail Sentence for Doctors Who Perform Abortions Past Gestational Limits

Source

KFF 2022 analysis of state statutes and laws; Guttmacher Institute. State Laws and Policies, State Policies on Later Abortions. As of May 2022.

The independent source for health policy research, polling, and news.

KFF 2022 analysis of state statutes and laws; Guttmacher Institute. State Laws and Policies, State Policies on Later Abortions. As of May 2022.

Lead exposure has well-documented long-term health and developmental impacts for children. As evidenced by the Flint Michigan water crisis, one way people may be exposed to lead is through water service lines, but exposure may also occur through other sources of lead in homes and neighborhoods. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Healthy People 2020 goals to reduce blood levels in children were exceeded, disparities persist, with lower-income households and children of color continuing to be at increased risk for lead exposure. Consistent with other preventative health screening trends, data suggest that lead screening may have declined amid the COVID-19 pandemic and exacerbated underlying disparities in early identification and intervention. As a major source of health coverage for low-income children and children of color, Medicaid can help to mitigate lead exposure and its impacts. Medicaid requires lead screening and testing for children that can facilitate early identification and intervention for lead exposure. In addition, there are a range of federal and state initiatives underway to address lead exposure and its health impacts.

To provide further insight into these issues, this brief examines:

In the U.S., individuals may be exposed to lead through multiple sources in their home or environment. Homes built before 1978 — when the federal government banned consumer uses of lead-based paint — likely contain lead-based paint, which may create lead dust when it peels or cracks. Older homes also may have pipes, faucets, and plumbing fixtures containing lead. Moreover, at least 6 million lead service lines exist in water delivery infrastructure, schools, and businesses. Lead can also be found in some products, such as toys and jewelry and in some imported food or medicine. Other sources of lead exposure may include certain jobs, such as manufacturing or construction, and/or contaminated soil.

Exposure to lead can seriously harm a child’s health, including damage to the brain and nervous system, slowed growth and development, learning and behavior problems, and hearing and speech problems. The effects of lead on the nervous system can cause lower IQ, decreased ability to pay attention, and under performance in school. The CDC indicates that these health effects are more harmful to children under age six, whose bodies are still developing and growing rapidly. In addition, younger children are at increased risk for exposure, since they are more likely to put their hands or other objects in their mouth, which may be contaminated with lead. In addition, lead exposure during pregnancy can increase risk for miscarriage, premature birth, and other developmental effects for babies. Blood lead levels rise after ingestion of lead and gradually decrease when exposure stops. Persistent blood lead level elevations may require therapy to remove heavy metals from the body to avoid irreversible damage to multiple body systems.

Disparities in lead exposure persist for lower-income households and neighborhoods and children of color. Data show that although Healthy People 2020 objectives to reduce overall blood levels in children have been exceeded, Black children and those living in households with incomes below 130% of the federal poverty level (FPL) remain at increased risk for exposure (Figure 1). Data were not reported for other broad racial/ethnic groups. Other research has found higher proportions of detectable and elevated blood lead levels among children with public insurance, who are more likely to be low income and found the share of children with elevated blood levels increased as degree of poverty increased. Similarly, research show that areas with higher blood lead levels are associated with low home ownership, high poverty, and residents who are a majority people of color. Some research also suggests some groups of Hispanic and Asian children are at increased risk for lead exposure. Similar patterns are observed among pregnant women, with studies finding higher levels of lead among Black and Hispanic women compared to White women, as well as higher levels among women residing in areas with higher crime, greater diversity, lower educational attainment, lower household income, and higher poverty. Lead poisoning also disproportionately affects refugee and other immigrant children due to both environmental exposures, such as resettling in pre-1978 housing, and potential exposure through cultural practices, traditional medicines, and consumer products. For example, refugees and other newcomer populations may use or consume imported products contaminated with lead, such as traditional remedies, herbal supplements, spices, candies with lead in the wrappers, cosmetics, or jewelry. Indigenous people may also be at increased risk of being exposed to lead through certain traditional practices, such as lead contamination of plants and animals in traditional diets, and older housing.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends testing blood for lead exposure because there often are no immediate symptoms when a child is exposed to lead. The amount of lead in blood is referred to as the blood lead level, which is measured in micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood. While no level of lead in the blood is identified as safe, the CDC uses a blood lead reference value (BLRV) of 3.5 micrograms per deciliter to identify children with blood lead levels that are higher than most children’s levels. This level is based on the 97.5th percentile of blood lead values among U.S. children ages 1-5 years from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; children with blood lead levels at or above the BLRV represent the top 2.5% blood lead levels. In 2021, the CDC decreased the reference value from 5.0 to 3.5 micrograms per deciliter to facilitate earlier intervention and identification of at-risk children even as overall lead levels among children in the U.S. have been decreasing. If a child has a blood level value above the BLRV, their doctor may recommend services for treatment and/or to remove lead from the environment.

There are no recommendations for universal lead screening among children, but screening is recommended for children and pregnant and breastfeeding women who are at higher risk for exposure. These include Medicaid-eligible children, those living in areas with older housing, and those in areas where higher shares of younger children have elevated blood levels as well as pregnant women in communities with high risk of lead exposure. The CDC also discourages breastfeeding among mothers with elevated blood lead levels. Given local variation in presence of risk factors, the American Academy of Family Physicians recommends following CDC screening guidelines in addition to using targeted screening questionnaires to identify children who may be at increased risk for lead poisoning. States also offer varied guidance for lead screening, management, and reporting

Consistent with other preventive health screening trends, data suggest that lead screening may have declined amid the COVID-19 pandemic and exacerbated underlying gaps and disparities in early identification and intervention. The CDC reports that from January-May 2020, 34% fewer U.S. children had blood lead level testing compared to the same period in 2019, with an estimate of 9,603 children with elevated blood lead levels missed. Between May 2019 and 2020, screenings fell by over 50%, with even larger fall offs in some states. For example, Michigan, Delaware, and Colorado all reported screenings fell by over 70% between May 2019 and 2020. The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measure for lead screening in children in Medicaid MCOs shows a decline from 70.0% in 2019 to 68.3% in 2020.

Medicaid covers lead testing through the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit and has specific requirements for lead screening of children. Guidance suggests that states must ensure that all children enrolled in Medicaid receive lead screenings at ages 12 months and 24 months; additionally, any child between 24 and 72 months with no record of a previous blood lead screening should receive one. Separate Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) programs do not have the same requirements for universal lead screening as Medicaid, although the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) encourages states to align CHIP and Medicaid screening policies. Despite requirements for lead screening, gaps in lead screening persist. Research has found that adherence to the Medicaid screening requirements is variable across states.

Beyond lead screening for children, consistent with Medicaid EPSDT benefit requirements, states are required to provide medically necessary diagnostic and treatment services for children identified with elevated blood lead levels. Additionally, Medicaid may provide case management and a one-time investigation to determine the source of lead for children with elevated blood lead levels. While Medicaid reimburses for lead investigations in the home or primary residence of a child with an elevated blood level, it does not cover lead abatement services.

Medicaid strategies to mitigate lead exposure include collaboration between Medicaid and state’s health departments and lead poisoning and prevention programs to reach children who have not received required blood lead screening tests. Partnering with providers can help with outreach and education efforts to promote screening and then to connect families to resources for lead mitigation within homes. Data sharing agreements between Medicaid and other state agencies can help identify children who may have not received lead screening. In addition, states can improve oversight and monitoring to include more frequent audits and meaningful enforcement or corrective action plans to increase lead testing. For example:

CMS guidance outlines a number of strategies with Medicaid managed care organizations (MCO) to improve lead screening for children. For example, states can include lead screening requirements in managed care contracts and require collection and reporting of quality measures like the HEDIS lead screening measure. Federal regulations mandate that states require Medicaid managed care plans to establish and implement an ongoing comprehensive quality assessment and performance improvement program for Medicaid services that includes Performance Improvement Projects (PIPs). PIPs may be designated by CMS, by states, or developed by health plans, but must be designed to achieve significant, sustainable improvement in health outcomes and enrollee satisfaction. States can also require managed care plans to implement PIPs focused on blood lead screenings or include lead screening improvements in the Quality Assessment and Performance Improvement Programs (QAPI). States can also link MCO payment incentives such as bonuses or penalties, quality add-on payments, or managed care capitation withholds to performance measures that promote increases in lead screening. For example:

Health Services Initiatives (HSI’s) authorized under CHIP allow for broader lead abatement activities than allowed under Medicaid. While Medicaid cannot be used to abate or remediate environmental risks, CHIP Health Services Initiatives (HSIs) can be used for this purpose. Under CHIP, states can implement HSIs to improve the health of low-income children and can include both direct services and public health initiatives such as lead education and case management. CMS guidance has provided examples of state-designed HSIs to increase blood lead screening rates for young children. A https://www.nashp.org/leveraging-chip-to-improve-childrens-health-an-overview-of-state-health-services-initiatives/ (including Indiana, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin) have HSIs focused on improving lead testing, prevention and paying for abatement, which includes efforts to remove lead-based paint, replacing tainted household components, and removal of lead hazards, many of which define an approach prioritizing high-risk neighborhoods.

Medicaid Section 1115 waivers may offer additional opportunities to address long-term health impacts of lead exposure and focus on impacted communities. For example, Michigan used a Medicaid section 1115 waiver to support its response to the Flint Water crisis (Box 1).

Box 1. Lead Exposure and Medicaid Interventions in Flint, Michigan

The Flint water crisis was a public health crisis that began in 2014, when the city switched its drinking water supply from Detroit’s system to the Flint River without adequate water treatment and testing for corrosion to prevent lead release from plumbing, which ultimately resulted in increased contamination and lead exposure for Flint residents. The crisis had greater impacts on people of color and under resourced areas, as Flint residents are predominantly lower income and disproportionately Black. Moreover, some Spanish-speaking residents in Flint did not learn about the water crisis until months after it began. Research showed increased incidence of elevated blood lead levels.

In response, Michigan sought and received expedited approval for a Section 1115 Medicaid waiver as well as a CHIP HSI to expand Medicaid eligibility for an estimated 15,000 children and pregnant women up to 400% of the Federal Poverty Line (FPL) in the Flint area, waive CHIP premiums for all children served by the Flint water system, and offer face-to-face targeted care management services to all impacted Medicaid-eligible children and pregnant women. Waiver evaluation data suggest high rates of lead screening among children and pregnant women covered under the waiver. In September 2021, CMS approved an extension of Michigan’s waiver, which demonstrated improvement in lead screening for children and eligible pregnant women.

A range of other efforts and funding helped provide lead abatement, create a registry to help monitor health outcomes, and coordinate services for lead-exposed individuals. Data from the Flint’s 2021 Lead Free report found that improvements residential water sources with high lead levels.

Beyond initiatives within Medicaid, the Biden administration and Congress have taken a range of actions focused on mitigating lead exposure and disparities.

Building on prior work, the EPA is providing additional support for addressing lead exposure among Tribal communities. In 2020, the EPA announced a new grant program of $4.3 million for Tribes to reduce lead in drinking water in schools. Since then, the EPA has worked with over 200 Tribal partners to design a curriculum to raise awareness in Tribal communities about childhood lead exposure, expand understanding of lead’s impact on children’s health and cultural practices and diets, and encourage actionable prevention of lead exposure. While limited data is available to assess the success of the curriculum, prior work has found that community-based health advisors and youth engagement focused on improving lead poisoning prevention (including washing hands before meals and snacks) lead to significant improvements for American Indian children. As part of the Lead Pipe and Paint Action Plan, the EPA will update the Safe Drinking Water Information System to support state and Tribal data management needs for inventories and allocate $2.9 billion in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to states, Tribes, and territories to remove lead service lines.

Key Tenets of the Biden-Harris Lead Pipe and Paint Action Plan

Get Resources to Communities. The EPA announced that it will allocate $2.9 billion in Bipartisan Infrastructure and encourage states to use funds to advance proactive lead line replacement programs, prioritizing disadvantaged communities and partnering with states to provide technical assistance to help marginalized communities overcome barriers to funding through State Revolving Fund (SRFs) programs. The 2022 allocation is the first of five years of $15 billion in dedicated EPA funding for lead serve lines states will receive from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. The EPA Office of Water will issue national program guidance to states on water infrastructure funding and will include directions on the $15 billion in dedicated lead service line funding. The EPA will additionally establish Technical Assistance Hubs in select regions with large concentrations of lead service lines. Furthermore, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) awarded $13.2 million to state and local government agencies through the Lead Based Paint Hazard Reduction (LBPHR) program, targeting specific high-risk communities initially.

Updates Rules and Strengthen Enforcement. On December 16, 2021, the EPA announced next steps to strengthen the regulatory framework on drinking water lead. The EPA announced additions to the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation: Lead and Copper Rule Revisions (in effect December 2021), outlining steps local water systems should take to achieve complete lead service replacement in addition to oversight and technical assistance for communities impacted by high lead blood levels.

Reduce Exposure in Disadvantaged Communities, Schools, Daycare Centers, and Public Housing. The CDC announced through the Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program (CLPPP) (authorized under the Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988) an intent to eliminate childhood lead poisoning as a public health problem by strengthening blood level testing, reporting, and surveillance (providing education and outreach to communities), and linking exposed children to services. Additionally, the goals of the new cabinet level partnership developed under the Action Plan include identifying priority areas for inter-agency coordination, funding alignment opportunities, addressing data gaps, and developing of coordinated guidance to reduce lead exposure in schools and childcare facilities. The HUD and the Department of Interior (DOI) will work to eliminate hazards in federally-assisted housing, including tribal housing by replacing lead services lines whenever water main feeder laces are replaced and mitigating or eliminating lead paint hazards when rehabilitating housing. The USDA will pursue actions through its Rural Development Mission Area Community Facilities Programs, which funds eligible projects for water filter station installation in schools and childcare facilities to prevent lead poisoning.

Long used as a tool to control spending and to promote cost-effective care, prior authorization in health insurance is in the spotlight as advocates and policymakers call for closer scrutiny about its use across all forms of health coverage.

Prior authorization (also called “preauthorization” and “precertification”) refers to a requirement by health plans for patients to obtain approval of a health care service or medication before the care is provided. This allows the plan to evaluate whether care is medically necessary and otherwise covered. Standards for this review are often developed by the plans themselves, based on medical guidelines, cost, utilization, and other information.

The process for obtaining prior authorization also varies by insurer but involves submission of administrative and clinical information by the treating physician, and sometimes the patient. In a 2021 American Medical Association Survey, most physicians (88%) characterized administrative burdens from this process as high or extremely high. Doctors also indicated that prior authorization often delays care patients receive and results in negative clinical outcomes. Another independent 2019 study concluded that research to date has not provided enough evidence to make any conclusions about the health impacts nor the net economic impact of prior authorization generally.

There is little information about how often prior authorization is used and for what treatments, how often authorization is denied, or how reviews affect patient care and costs.

A 2021 KFF Issue Brief found that most (99%) Medicare Advantage enrollees are in plans that require prior authorization for some services. In addition, 84% of Medicare Advantage enrollees are in plans that apply prior authorization to a mental health service.

A recent report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found 13% of prior authorization denials by Medicare Advantage plans were for benefits that should otherwise have been covered under Medicare. The OIG cited use of clinical guidelines not contained in Medicare coverage rules as one reason for the improper denials, as well as managed care plans requesting additional unnecessary documentation. The OIG recommended and HHS agreed that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should take a closer look at the appropriateness of clinical criteria used by Medicare Advantage plans in making coverage determinations.

Concern about the use and impact of prior authorization by health plans has prompted consideration of various measures to regulate the practice or make it more transparent.

Clinical coverage criteria. The use of health plans’ own “home grown” clinical criteria to make coverage decisions has come under scrutiny. California, for example, now prohibits plans from using their own clinical criteria for medical necessity decisions, requiring commercial insurers to instead use criteria that are consistent with generally accepted standards of care and are developed by a nonprofit association for the relevant clinical specialty. Of note, state laws like this would not apply to self-insured employer-sponsored plans.

Use in behavioral health. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) requires commercial insurers, employer-sponsored plans, and certain Medicaid plans to document the use of prior authorization for both medical and behavioral health care covered services. Plans must provide a comparative analysis that includes the rationale and evidence for applying prior authorization, as well as all other nonquantitative coverage limits. While compliance with this requirement has been slow according to a recent federal agency report to Congress, enforcement at the federal and state level has increasingly required plans to eliminate prior authorization for specific behavioral health treatment due to alleged parity violations.

Transparency Increasing transparency about how the prior authorization process works is also gaining some momentum. H.R. 3173, with 306 cosponsors, would require Medicare Advantage insurers to report to HHS on the types of treatment that requires prior authorization, the percentage of prior authorization claims approved, denied, and appealed. Similarly, some states have required this type of data reporting as part of their mental health parity implementation, while some regulators urge more reliance on data reporting for MHPAEA compliance. Such transparency data proposals are similar to current law requirements under the Affordable Care Act for private plans to report to data on claims payment practices and denials. While this federal law applies to all commercial insurers and employer-sponsored plans, to date it is largely un-implemented, with only limited reporting required of non-group plans sold through HealthCare.gov.

Setting standards for prior authorization. Other current law standards regulating prior authorization are limited.

Administrative reforms. Last year CMS finalized a regulation to streamline the prior authorization process for Medicaid and for private health plans offered on HealthCare.gov through new electronic standards and other changes. While the rule was later withdrawn, similar changes may still be forthcoming from HHS. H.R. 3173 would require CMS to implement an electronic prior authorization program for Medicare Advantage plans with capacity to make real-time decisions. The insurance industry generally has supported electronic prior authorization reforms to expedite review times.

Debate over further standards to limit the use or regulate prior authorization may well involve tradeoffs between claims spending versus access to care for patients and administrative burden for providers. Promoting transparency of this process and how it works in practice could help inform what those tradeoffs might involve.

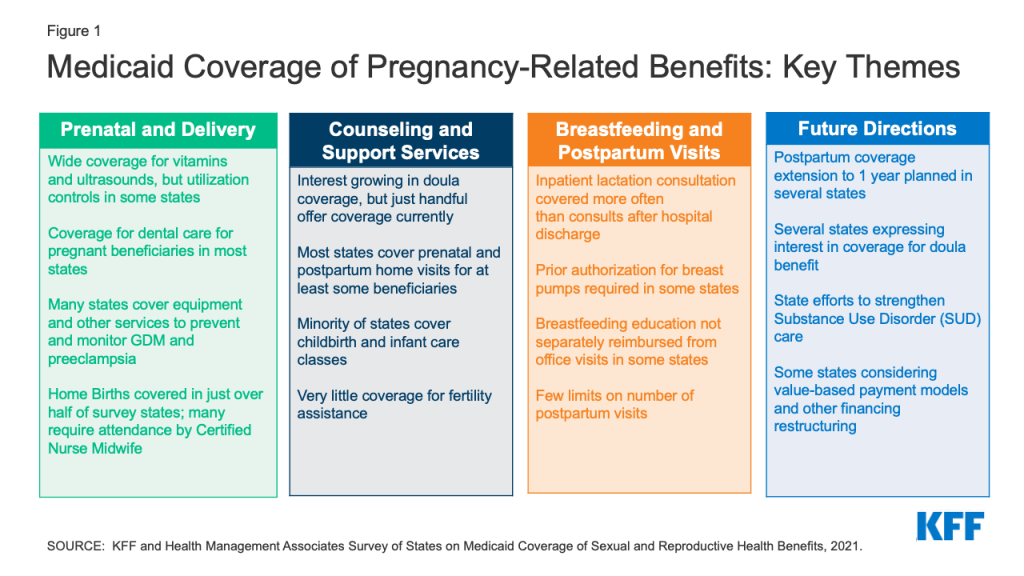

Medicaid funds more than four in ten births in the United States and more than half in several states. A new KFF report of results from a survey of 41 states and DC finds that on the whole, states offer broad coverage for basic pregnancy-related services. Most states also reported that they are working on ways to strengthen Medicaid coverage of maternity services and are trying to respond to concerns about coverage continuity and scope of benefits.

The new report outlines four main themes regarding state pregnancy- related benefits: Prenatal and delivery; counseling and support services; breastfeeding and postpartum visits; and future directions. Some key highlights from the report include

Many states reported efforts to extend the postpartum coverage period, which was the most reported new initiative states would be implementing in 2022. For the most up to date information on Medicaid postpartum coverage extensions, visit the online KFF tracker.

The Medicaid program finances more than four in ten (42%) births in the United States, and more than half of births in several states. In recent years, policymakers have devoted new attention to maternal health in response to rising rates of pregnancy-related deaths and the substantially higher rates experienced by Black and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people. This is a particular concern for the Medicaid program, which finances approximately two-thirds of births among Black and AIAN individuals nationally.

The range of pregnancy-related services that states cover is shaped by many factors, with federal law setting the following baseline requirements that states must follow:

While federal law establishes a floor for benefits and eligibility, states have significant latitude to set income eligibility levels, define specific maternity care services, and apply utilization controls such as prior authorization and preferred drug lists (PDL). To understand how states cover reproductive health services under Medicaid, KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation) and Health Management Associates (HMA) conducted a survey of states between June 2021 and October 2021 about the status of Medicaid benefit policies across the nation. This report presents findings on states’ coverage of maternity care services under Medicaid as of July 2021. Forty-one states and the District of Columbia responded to the survey. States that did not respond to the survey are: Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Minnesota, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, and South Dakota. Key themes from the survey findings are summarized in Figure 1. A companion report with findings on coverage of family planning benefits is available here.

Several states are considering efforts to enhance maternity benefits, particularly extending the postpartum coverage period, adding doula benefits, and developing targeted initiatives to address substance use disorders for pregnant and postpartum beneficiaries. Under federal Medicaid rules, pregnancy-related coverage lasts through 60 days postpartum, but in recent years, there has been interest in extending coverage through the first year postpartum among policymakers at the federal and state levels. Extending postpartum Medicaid coverage was the most commonly reported new initiative that states are considering with regard to maternal health. KFF is tracking state activity on this policy, and the most up to date information is available in this tracker.

While few states had doula benefit in place as of July 2021, at least 11 other states are considering adding coverage for doula benefits, including four states reporting they planned to begin coverage by the end of 2022. A number of states also reported that they are trying to strengthen care for pregnant and postpartum beneficiaries with substance use disorders, with a focus on improving access to treatment services.

Medicaid covers more than four in ten births nationally and the majority of births in several states. This survey asked states about the specific maternity services they cover. The range of pregnancy-related services that states cover is shaped by many factors, and states have significant latitude to set income eligibility levels, define specific maternity care services, and apply utilization controls such as prior authorization and preferred drug lists (PDL).

While states can vary in the benefits they provide to some pregnant individuals depending on their eligibility status, the vast majority of states provide the full Medicaid package to all pregnant beneficiaries. A majority of states contract with managed care organizations (MCOs) under a capitated structure to deliver Medicaid services, and plans may vary in their coverage of specific services. This survey’s questions focused on state Medicaid policies and coverage under fee-for-service, and these policies typically form the basis of coverage for MCOs.

In addition to benefits, states also have discretion regarding reimbursement methodologies which also affect beneficiaries’ access to maternity care services. For example, maternity care is often reimbursed as a bundled payment that covers all professional services provided during the perinatal period, including prenatal care, labor and delivery, and postpartum care, and a separate facility fee. This kind of payment for an episode of care can help states manage costs and also provide incentives for coordination of comprehensive care across maternity providers. Bundled payments, however, also make it more difficult to track the delivery of component services that may be included in the bundle, such as health education or counseling.

This report presents detailed survey findings from 41 states and DC on fee-for-service coverage and utilization limits for Prenatal care and Delivery, Fertility Services, Counseling and Support Services, Substance Use Disorder Services, and Breastfeeding Supports and Postpartum Care.

Prenatal care services monitor the progress of a pregnancy and identify and address potential problems before they become serious for either the mother or baby. Increasing the share of pregnant women who begin care in the first trimester is one of the national objectives of the federal government’s Healthy People 2030 initiative. Routine prenatal care encompasses a variety of services, including provider counseling, assessment of fetal development, screening for genetic anomalies, prenatal vitamins that contain folic acid and other nutrients, and ultrasounds, which provide important information about the progress of the pregnancy. Access to routine prenatal care provides an opportunity to identify any problems with the pregnancy early on and is associated with lower rates of some pregnancy-related complications.

All responding states reported covering prenatal vitamins and ultrasounds for pregnant people, but some states impose utilization controls. While states are not required to cover over-the-counter drugs, they must cover nonprescription prenatal vitamins. The majority of states reported that coverage for prenatal vitamins and ultrasounds aligned across coverage eligibility groups, with exception of Oklahoma (for prenatal vitamins) and Utah and Mississippi (for ultrasounds).

States reported using utilization controls to manage the benefit for prenatal vitamins such as days limits, generic requirements, and inclusion on a Preferred Drug List (PDL) (Table 1). Two states, Iowa and Pennsylvania, require prior authorization, although Pennsylvania noted that it was only required for non-preferred prenatal vitamins. Alaska and Wyoming reported they require prescriptions for Medicaid to cover prenatal vitamins. Washington reported that not all formulations of vitamins are covered. The state also noted that there may be coverage variation between MCOs.

Quantity limits and medical necessity requirements were the most common utilization controls states reported for ultrasounds. Most states reported that ultrasounds were limited to two or three per pregnancy, with additional allowed if medically necessary. Pennsylvania only covers one ultrasound per pregnancy, while Utah allows for 10 ultrasounds in a 12-month period. Oklahoma covers two ultrasounds per pregnancy but allows one additional to identify or confirm a suspected fetal or maternal anomaly. Two states, Indiana and West Virginia, only cover ultrasounds with “medical necessity.” Indiana does not cover routine ultrasounds or ultrasounds for sex determination, and West Virginia covers ultrasounds in accordance with criteria for high-risk pregnancies established by ACOG.

There are a variety of support services that can aid pregnant and postpartum individuals with pregnancy, delivery, and childrearing. These include childbirth education classes, infant and parenting education classes, and group prenatal care.

Less than half of responding states reported that they cover childbirth and parenting education for pregnant people. Fifteen states provide coverage for childbirth education classes through their Medicaid program, and 14 cover infant care/parenting education classes (Table 2). Eleven states cover both services—Arizona, Colorado, DC, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. States that cover these classes report aligning coverage across all eligibility coverage pathways available in the state.

Most states that cover these programs provide separate reimbursements to providers. Eleven states reimburse separately for childbirth education, and five reimburse as an office visit component, while seven reimburse separately for infant care/parenting classes. Colorado limits childbirth and parenting education to provision during routine prenatal visits. Wisconsin only provides childbirth and parenting education to women if they are enrolled in the state’s Prenatal Care Coordination program for those at higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Only twelve of the responding states reported covering group prenatal care for their Medicaid population. Group prenatal care typically involves a group of eight to ten pregnant people meeting with a health provider over ten visits for about 90 minutes to two hours to discuss questions and concerns. Research suggests that pregnant people who participate in group prenatal care have more knowledge about prenatal care, feel more prepared for labor and delivery, have lower rates of premature births and babies with higher birth weights, and are more likely to begin breastfeeding. Three states, California, Texas, and Utah, limit the number of visits or hours for group prenatal care. Texas limits group prenatal care to a maximum of 10 visits per 270 days and counts group visits toward the total combined limit of 20 prenatal visits per pregnancy. Utah maintains a limit of eight sessions in a 12-month period. California Medi-Cal will cover up to 27 hours. Colorado specified that group prenatal care is only covered for individuals enrolled in special programs for beneficiaries with higher risk pregnancies Maryland currently does not cover group prenatal care but reported the state is working towards it for 2022.

Thirty-nine of the responding states cover dental services for pregnant Medicaid enrollees. Five of these states limit coverage to emergency dental services. There is some evidence that pregnant people are at higher risk for periodontal disease during pregnancy and that a mother’s dental health status is linked to her child’s future dental health status. While state Medicaid programs must cover dental services for children, including oral health screenings and diagnosis and treatment services, federal law does not require states to cover dental benefits for adults. States can choose to cover dental benefits and have considerable discretion in defining Medicaid adult dental benefits. In 2021, federal legislation was introduced that would require state Medicaid and CHIP programs (and some private plans) to cover dental health services for pregnant and postpartum individuals, but currently there is no national requirement.

Prior authorization, spending limits, and limiting coverage to emergency dental services were common utilization controls reported by states (Table 3). Arizona, Hawaii, Maine, Texas and West Virginia reported that they only cover emergency dental care. In addition, Hawaii also covers procedures needed to control or relieve pain, bleeding, elimination of infections, and management of trauma.

The majority of the responding states (36 out of 40) reported covering low-dose aspirin for pregnant people under their Medicaid Programs. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends low-dose aspirin as a preventive medication for pregnant people at risk for preeclampsia, a serious health condition characterized by high blood pressure and signs of damage to organ systems like kidneys and liver that occurs after the 20th week of pregnancy. Worldwide, preeclampsia is the second cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, and it affects one in five pregnancies beyond 20 weeks in the United States. During 2014–2017, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy accounted for 6.6% of maternal deaths in the United States.

Five states impose utilization controls on low-dose aspirin. Kansas and Louisiana have quantity limits, while Connecticut covers aspirin as a pharmacy benefit with a diagnosis of preeclampsia. Iowa requires prior authorization, and Wyoming requires a prescription for coverage. Alaska, Florida, Oklahoma, and Virginia do not cover low-dose aspirin under their programs (Table 4).

Most responding states (31 of 41) cover Blood Pressure (BP) monitors for home use as a pregnancy-related service, while few states cover scales to monitor weight. These tools can be helpful for monitoring the health of the pregnancy, particularly for people at risk for preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or other pregnancy-related conditions. Five states (Alaska, California, Missouri, Mississippi and North Carolina) noted coverage was subject to medical necessity, and two states have limited coverage to one blood pressure monitor every five years (Pennsylvania) or every three years (North Carolina). Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, and Mississippi require prior authorization for blood pressure monitor coverage, although Connecticut noted that it only requires prior authorization for wrist monitors, not upper arm monitors. New Jersey reported they require a prescription to cover monitors. All but two states, Utah and West Virginia, indicated that coverage policies were aligned across eligibility groups. While both blood pressure monitors and scales can be useful for pregnant people to monitor their health, only nine states—Arizona, California, Delaware, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oregon, Utah, and Vermont, cover weight scales for pregnant people.

The majority of states cover continuous glucose monitors and nutritional counseling to support pregnant people with gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes is a type of diabetes that appears during pregnancy for the first time. In the United States,10% to 20% of all pregnancies are affected by gestational diabetes, which can increase a pregnant person’s risk of having high blood pressure during pregnancy and developing Type 2 Diabetes after pregnancy. Both the USPSTF and HRSA recommend that pregnant people get screened for gestational diabetes at around 24 weeks gestation.

Thirty-five of the responding states reported covering continuous glucose monitors (Table 5). Six states, Alaska, Connecticut, Florida, Kansas, Oregon, and Wisconsin do not cover them. Mississippi, North Carolina, Nevada, Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington require prior authorization to cover glucose monitors, and three states—California, Louisiana, and Montana—have medical necessity requirements. Louisiana covers monitors for adults with poorly controlled Type 1 Diabetes, while Montana will cover them for those with a gestational diabetes or diabetes mellitus diagnosis.

Thirty-four responding states cover nutritional counseling for pregnant people. Five of these states (Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, and Texas) reported that they covered nutritional counseling as part of a routine prenatal care visit with a medical provider, not as a separate visit with a nutritional counselor. Maine covers these visits only when they are provided by a physician, dietician, or family planning agencies. Alaska, North Carolina, Nevada, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Utah limit the number of visits or hours that they cover.

More than half of responding states (25 of 42) cover home births under Medicaid. While clinicians, maternal health researchers, and birthing parents have been discussing home births for decades, interest has grown since the start of the COVID pandemic. New Jersey reported coverage for home births, but only in two of its MCOs. One state (Texas) reported requiring a prior authorization request from a physician during the third trimester for a delivery by a Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM) indicating that the patient is not at high risk for complications and is suitable for a home delivery. Several states also commented on provider requirements, stating that home births must be attended by a physician or certified nurse midwife (CNM).

The majority of responding states (35 of 41) reported no limits on the number of covered postpartum visits. Guidelines for postpartum care have evolved over time. ACOG and other professional organizations recommend that postpartum individuals have contact with their obstetric care providers within the first three weeks postpartum, with ongoing care as needed. This means that multiple visits may be needed for many people after delivery. However, in many states, pregnancy coverage ends 60 days postpartum. In states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion, many people can remain on Medicaid after that time as parents or qualify for subsidies to purchase private insurance in the Marketplace. In non-expansion states however, many postpartum people lose coverage after pregnancy Medicaid ends, falling into the coverage gap because their income is too high to qualify for Medicaid as a parent but too low to qualify for subsidies in the Marketplace, cutting off access to postpartum visits and other health care services just two months after childbirth. (Note: Disenrollment from Medicaid has been suspended during the Public Health Emergency).

Six states reported limits on postpartum visits (Table 6). Rhode Island reported a limit of five postpartum visits, while Alabama reported a limit of two visits, and four states (Kansas, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Vermont) reported a one-visit limit. Of the four states reporting a one-visit limit, Vermont indicated that the limit did not apply in the case of a twin delivery. Louisiana reported the state covers one visit defined as a postpartum visit but that there were no limitations on additional visits. While Texas and North Carolina reported no limits on the number of postpartum visits, Texas indicated having one postpartum procedure code that could be reimbursed once per pregnancy that covers all postpartum care regardless of the number of visits provided. Similarly, North Carolina reported that postpartum care is billed under a global postpartum package code, regardless of the number of visits provided.

Almost all responding states reported that they cover postpartum depression screening and treatment. Rhode Island was the only state that reported that it doesn’t cover postpartum depression screening, and Virginia was the only state reporting no coverage of postpartum depression treatment. More than half of the states reporting coverage of postpartum screening indicated that screening services were reimbursed separately while the rest reported that screening was reimbursed as a component of an office visit. Maine indicated that screening can be reimbursed either way depending on the provider that is billing. Only a few states mentioned imposing utilization controls on depression screenings: California (two per year per pregnant or postpartum enrollee); Iowa (limit of two screenings); Kansas (three prenatal and 5 postpartum); and Pennsylvania (one per day). Three states (Oklahoma, Texas, and Washington) noted that postpartum depression screenings are covered as part of an infant or child Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) screening. Several states noted that utilization controls on postpartum depression treatment would depend on the behavioral health treatment service provided. For example, Mississippi noted that inpatient stays required prior authorization. Two states (Oklahoma, Pennsylvania) also noted prior authorization requirements for non-preferred medications or a generic requirement.

Only three states—Indiana, New Jersey, and Oregon—reported covering doula services as of July 1, 2021. Minnesota, which did not respond to this survey, has also covered doula services through their state Medicaid program since 2014. A doula is a trained non-clinician who assists a pregnant person before, during and/or after childbirth, by providing physical assistance, labor coaching, emotional support, and postpartum care. Pregnant women who receive doula support have been found to have shorter labors and lower C-sections rates, fewer birth complications, are more likely to initiate breastfeeding, and their infants are less likely to have low birth weights. In recent years, there has been growing interest in expanding coverage of doula services through Medicaid, in part due to the high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity in the United States and the disproportionately high rates of poor maternal outcomes experienced by Black and Native American pregnant people. Federal legislation has been introduced to expand coverage of doula services through Medicaid, and some states are taking steps to include coverage through their state programs.

Medicaid policy requires states to cover certified medical professionals. Many doulas are trained by community-based organizations (CBOs), but most states do not recognize doula certification by CBOs. The three states that reported covering doulas have taken different approaches (Table 7). Indiana reported they cover doula services through community health workers and cover approximately 12 hours per month. New Jersey covers eight visits during the perinatal period, but if the pregnant person is under the age of 20, the state covers 12 visits. Oregon covers a minimum of two visits and has no maximum number of visits. Oregon includes doulas who have completed a training program in their state registry of certified health workers, while neither Indiana nor New Jersey has a doula registry. The states have also approached reimbursements differently. Oregon reimburses doulas directly, while Indiana provides reimbursements indirectly, through their billing or supervising provider. New Jersey allows for both direct and indirect billing. There is a wide range in how much state Medicaid programs are reimbursing doulas for their services. Oregon pays a flat fee of $350 per pregnancy, while Indiana reported that the state pays $2,095 per pregnancy.

Four additional states reported that they would begin covering doula services in 2022. Massachusetts plans to submit a State Plan Amendment (SPA); Virginia will begin coverage on April 1, 2022 (and will have a state registry); and Maryland is moving towards having doula coverage in 2022. Nevada began coverage on January 1, 2022 and reported additional details which can be found below in Table 7. Furthermore, several states reported that they are considering adding doula benefits under Medicaid, which is discussed later in this report in the section entitled, “New Initiatives.”

Very few states cover fertility-related services under Medicaid. Fertility care encompasses a spectrum of services, including counseling, diagnostic, and treatments such as medications, egg freezing, intrauterine insemination (IUI), and in vitro fertilization (IVF). Eleven states reported that they cover fertility counseling outside of a well woman visit (Table 8). Eleven states cover diagnostic testing related to fertility, although some cover tests only for medical reasons other than for fertility. While federal rules require states to cover most prescription medications under Medicaid, there is an exception that allows states to exclude coverage for fertility medications. Just four states (California, Illinois, New York, and Wisconsin) reported coverage of fertility medications such as HMG for women under their Medicaid programs. Coverage is aligned across eligibility groups for the most part, except that California does not cover fertility services under their family planning SPA. Illinois is the only state that reported coverage for all fertility services asked in the survey under their Medicaid program, including IVF, IUI, and egg freezing.

Routine prenatal care typically includes ultrasound and blood marker analysis to determine the risk of certain congenital conditions such as down syndrome. While these tests are effective screening tools to determine risk, they are not diagnostic. If the results of screening tests are abnormal, genetic counseling is recommended and additional testing such as chorionic villus sampling (CVS) or amniocentesis may be needed.

Most responding states (38 of 40) cover 1st trimester genetic screening for pregnant women. Many of the states require prior authorization and specific medical conditions must be met such as high-risk pregnancy conditions and age-related risk (Table 9). Several states noted specific medical necessity requirements for the relatively new cell-free DNA tests. Nevada reported that they do not cover cell-free DNA tests.

All responding states reported covering amniocentesis, and most states (39 of 42) cover Chorionic Villus Sampling (CVS). Some states provide coverage for these screening tests subject to medical necessity requirements. California limits CVS to individuals in the first and/or second trimester of pregnancy. New Jersey covers CVS for those 35 years or older. Alabama, Indiana, and Mississippi reported that they do not cover CVS.

Most responding states (32 of 42) cover genetic counseling. Most states reported that they cover genetic counseling during pregnancy, but some states, such as Alaska and Connecticut, report that they cover it as part of an office visit. This may be in part because genetic counselors are not recognized as a provider type in some states. Several states also report that they provide coverage subject to medical necessity requirements such as high-risk pregnancy. Washington limits coverage to one initial prenatal genetic counseling encounter and two follow-up encounters per pregnancy to occur not later than 11 months after conception.

There is a range of services outside of traditional obstetric care that can support low-income people during pregnancy. Case management is a Medicaid benefit that provides assistance with coordinating and obtaining external supports such as nutritional counseling and educational classes. Medicaid’s non-emergency medical transportation (NEMT) benefit facilitates access to care for low-income beneficiaries who otherwise may not have a means of getting to health care appointments. A broad range of transportation services, such as taxicabs, public transit buses and subways, and van programs, are eligible for federal Medicaid matching funds.

Most responding states provide case management services to at least some pregnant beneficiaries. Several states noted that case management services were limited to high-risk pregnancies, qualifying conditions, targeted populations, and/or first-time mothers, and a few states reported specific service limits, such as a certain number of units or hours per month (Table 10). Two states (California and Utah) reported that service limits were determined by “medical necessity,” and one state (Connecticut) noted that case management was covered as part of overall prenatal reimbursement and not reimbursed separately. Four states—Arizona, Louisiana, Michigan, and Nevada—reported that they did not provide case management services to pregnant women. Of the 36 states covering case management services for pregnant women, the vast majority (34) indicated that coverage policies were aligned across eligibility groups. Two states reporting coverage only in the case of high-risk pregnancies (Alaska and Mississippi) indicated that their coverage policies were not aligned.

All responding states reported covering NEMT services for pregnant beneficiaries, as is federally required. Only four states (Alaska, Iowa, Mississippi, and Utah) reported that NEMT coverage policies were not aligned across eligibility groups including Mississippi, which provides an NEMT benefit only to beneficiaries with full Medicaid benefits, and Iowa, which does not cover NEMT services for ACA expansion adults. A few states noted that NEMT services were subject to prior authorization, limited to 300 miles per day (Pennsylvania), limited to medical providers within 125 miles (West Virginia), or must be requested by a provider (Massachusetts).

Most responding states cover both prenatal and postpartum home visits. Home visits are typically visits by nurses or other clinicians to pregnant and postpartum people to provide support with medical, social, and childrearing needs. There are a number of different models of home visiting programs, and some are associated with improvements in birth outcomes and early childhood measures. There are multiple streams of financing for home visiting programs in states, including through Medicaid, the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program, and state public health departments.

Several of the responding states noted that home visiting benefits were limited to high-risk beneficiaries, subject to prior authorization, or as part of a Nurse Family Partnership program for first-time mothers Oklahoma, South Carolina. In contrast, Indiana reported that both prenatal and postpartum home visits were provided through community health workers, and Michigan reported that, in addition to medically necessary prenatal and postpartum home visits, every pregnant and infant beneficiary is eligible for the Maternal Infant Health Program (MIHP) – an evidence-based preventive home visiting program. New York allows all Medicaid beneficiaries who have given birth at least one postpartum home visit.

Five states (Florida, Montana, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wyoming) reported that they did not cover prenatal or postpartum home visits, although Tennessee indicated that while not required, MCOs provided varying levels of coverage, and Wyoming reported that the Department of Public Health covers postpartum visits.

There is growing attention to the impact of substance use on pregnant and postpartum people as well as their infants. The federal Substance Use Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act requires that states provide certain services for pregnant and postpartum people, including Medication Assistance Treatment (MAT), which includes medications such as buprenorphine and naloxone. In addition to MAT, the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recommends a variety of other services to support the treatment and recovery of people with substance use disorder, but states are not required to cover these under Medicaid. The SUPPORT Act also established a new state plan option to make Medicaid-covered inpatient or outpatient services available to infants with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) at a residential pediatric recovery center (RPRC).

Most responding states offer some SUD benefits to pregnant people beyond what is required by the SUPPORT Act. Of the 42 responding states, 36 reported offering expanded SUD benefits beyond the required benefit of MAT mandated by the federal SUPPORT Act. Of these 36 states, 27 reported offering all or most of the ASAM-defined levels of care,21 including residential care (Table 11). Five states reported covering outpatient SUD services, but not residential services, and two states did not specify the expanded services covered. As of July 1, 2021, ten states reported covering residential pediatric services for infants with NAS.

All but two of the responding states (Iowa and Maine) reported that coverage policies for SUD services for pregnant women were aligned across all Medicaid eligibility pathways: Iowa indicated that ACA expansion adults may receive SUD services only through the state’s MCO model if the member is determined to be “medically frail,” and Maine reported that its Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) program was specific to individuals who are pregnant or postpartum.

A range of supports can help parents initiate and maintain breastfeeding, including breast pumps, lactation counseling by certified consultants, and educational programs, which can begin during pregnancy and continue after the birth of a child. States are required to cover breast pumps and consultation services for Medicaid expansion beneficiaries under the ACA’s preventive services requirement. For non-expansion states, there is no federal requirement for coverage of breastfeeding services.

Some states include coverage for breastfeeding education and lactation consultation as part of global maternity care payments and do not reimburse for them as separate services. Several states indicated that breastfeeding education is covered as part of an office visit or global maternity fee, rather than reimbursing separately, for example, for an instructor-led class. Nevada reported the service may be reimbursed either separately or as part of a physician office visit or daily hospital per diem rate. Three states reported limits to breastfeeding education: Wisconsin indicated that individuals must be enrolled in the state’s Prenatal Care Coordination program to receive covered breastfeeding education; North Carolina covers breastfeeding education only as a part of childbirth education classes; and Utah limits breastfeeding education to eight 1-hour units during a 12-month period. Indiana notes that breastfeeding education is provided through community health workers.

Lactation consultation services are more commonly covered in the hospital setting, compared to outpatient and home visits. Lactation support can be provided in multiple settings in the postpartum period, including in the hospital before discharge, at outpatient visits, or at home. States most frequently reported covering services in the hospital (Table 12). States also differ in whether the service is included as part of the global maternity feel or paid separately. Among states that cover hospital-based individual lactation consultants, 23 cover them as part of a DRG/global fee component, and four reimburse them separately. Slightly more than half of states (13) that cover outpatient/clinic based individual lactation consultants separately reimburse them compared to the 11 that include them as an office visit component. Home visits can be particularly helpful for new parents trying to breastfeed, care for a newborn, and recover from childbirth. Among states that cover lactation consultants as part of a home visit, roughly half (9 of 19) separately reimburse the service instead of including it as part of a home visit component. Washington only covers hospital-based lactation consultants, noting that many Medicaid beneficiaries receive lactation support from WIC clinics, which are funded separately from Medicaid, and Wyoming noted that although Medicaid does not cover them, home visits are covered under the state’s public health department. New Jersey reported that in FY2022, the state will allow lactation professionals to enroll as new providers, expanding lactation support services.

Several states use utilization controls such as quantity limits to manage these services: Michigan (two clinic- or home-based lactation visits per pregnancy), Oklahoma (six clinic- or home-based sessions per pregnancy), and North Carolina (six 15-minute clinic-based units a day with a lifetime maximum of 36 units if the infant has a chronic, episodic, or acute condition). Eight states reported that they do not cover any breastfeeding education and lactation consultation services (Arizona, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Texas).

A majority of responding states cover both electric and manual breast pumps, but some report using various utilization controls such as prior authorization or quantity limits. All but five of the responding states cover electric breast pumps, and 32 of 42 responding states cover manual pumps. Of the states that do not cover breast pumps in the Medicaid program, three—Nevada, Oklahoma, and South Carolina—report that pumps are provided through the state’s Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program.

Eight states impose quantity limits on the coverage of pumps, ranging from one every six months to one per lifetime. Several states require prior authorization for coverage of at least one type of breast pump: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Missouri, Texas, and Washington. Colorado only covers pumps for premature infants and those in critical care if the infant is anticipated to be hospitalized for more than 54 days.

Of the responding states, 15 reported that they offer all of the breastfeeding supports that the survey asked about: breastfeeding education, lactation consultations in the hospital, outpatient, and home settings, and electric and manual breast pumps (Figure 2).

More than half of states reported that they are planning to implement at least one Medicaid initiative to address birth outcomes and/or maternal health in FY2022. Given the Medicaid program's large role in maternity care, states have many opportunities to strengthen the health of pregnant and postpartum people as well as newborns.

The most commonly reported new initiatives that states reported were related to extending pregnancy eligibility through 12 months postpartum (Table 14) as allowed by an option in the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Federal policy requires that pregnancy-related eligibility last through 60 days postpartum, but states have options to extend coverage beyond that time period. Medicaid eligibility levels for pregnant individuals are higher than eligibility levels for parents in most states, so women may lose Medicaid coverage at the end of the 60-day postpartum period, particularly in states that have not implemented the ACA Medicaid expansion, where eligibility for parents remains very low. A provision in ARPA, that went into effect on April 1, 2022, allows states to now extend pregnancy coverage through 12 months postpartum by filing a state plan amendment (SPA). There has been a extensive activity at the state level since this survey was fielded, and the most up to date information is available in the online KFF Tracker on Medicaid Postpartum Coverage (Note: Currently postpartum people covered by Medicaid can remain on the program beyond 60 days because of a continuous enrollment requirement enacted in 2020 that lasts through the COVID public health emergency.)

To date, more than half of states have taken steps toward lengthening the postpartum coverage period beyond 60 days. This includes several states that have not yet opted to expand full Medicaid to all adults under the ACA, where the likelihood of losing coverage two months after delivery is higher than in expansion states. However, not all of these extensions meet the criteria for the ARPA option. For example, Missouri is extending postpartum coverage only for those with substance use disorders, whereas the ARPA option requires extension for all postpartum beneficiaries. Conversely, some states are proposing more expansive coverage extensions. Massachusetts, California, and Illinois are all proposing postpartum coverage extension for individuals regardless of immigration status, and Washington state has enacted legislation that would extend postpartum coverage, including for individuals who may not be federally qualified and for those who were not on the state’s Medicaid program during pregnancy. In addition to coverage extension, some states reported other efforts to strengthen postpartum care such as raising rates of postpartum visits among Medicaid beneficiaries, but they did not provide details about how they would do this.

Eleven states reported that they are considering adding doula services as a covered benefit. Most of these initiatives are in early stages, with some states piloting the benefit in selected counties and some states still in the planning stage. However, some states are further along with providing this benefit. This survey asked states to report benefits implemented as of July 1, 2021. In addition to the three states that already cover doula services, Maryland, Nevada and Virginia reported that their doula benefits would begin in 2022.

Eight states explicitly mentioned initiatives to address substance use or mental health services for pregnant or postpartum beneficiaries. For example, Colorado and Maine reported plans to implement a Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) model to integrate substance use treatment and obstetric services for pregnant and parenting individuals. In addition, six states reported that they are in the process of implementing or expanding home visiting benefits, which may be designed for higher risk pregnancies.

Other types of new initiatives reported by more than one state include: adoption and implementation of Medicaid MCO or provider performance measures/incentives to improve maternal health outcomes value-based purchasing arrangements or bundled maternity payments; community health workers (California and Nevada), and telehealth services for prenatal and postpartum care (North Carolina); multi-agency collaboration to address maternal health outcomes and disparities (Arizona, Missouri, Oklahoma, Texas); and addressing social determinants of health (New York, Oklahoma). At least two states (Arizona, Montana) have efforts under way to provide supports for maternal mental health. A couple of states have planned initiatives to expand contraceptive access, either allowing over-the-counter access to (Illinois) and authorizing pharmacists to dispense self-administered hormonal contraceptives without a prescription (Nevada). This is discussed in more depth in a related report. Virginia reported that the state has launched the FAMIS Prenatal Coverage for uninsured pregnant individuals who don’t qualify for other full-benefit coverage groups because of their immigration status. Applicants do not need to provide immigration documents or a Social Security number to enroll in this new coverage, but do need to meet other eligibility criteria, including income level.

This survey was conducted at a time of greater national attention to the state of maternal health, an area where Medicaid has long played a major role. On the whole, this survey finds that states offer broad coverage for basic pregnancy-related services, but that some impose utilization controls. Coverage for services outside of the medical setting is mixed, with most states covering home visits but limited coverage for educational classes and home-base lactation consultations. Very few states offer any coverage for fertility assistance services.

Most states also reported that they are working on ways to strengthen Medicaid coverage of maternity services. In particular, some states have already extended the postpartum coverage period to one year, while several others are considering this option. Several states have also expressed interest in covering doula benefits and better integration of substance use treatment services for pregnant and postpartum people. Many of these issues have also been raised by clinical groups as priority areas for improving maternal health.

The authors thank the numerous staff members in state Medicaid agencies who participated in the survey. The authors also thank the following individuals, who provided input in the survey questionnaire, data management, and analysis: Jim McEvoy and Kraig Gazley of Health Management Associates; Nan Strauss, Yuki Davis, and Jenny Chang of Every Mother Counts; Michelle Moniz of University of Michigan Institute of Healthcare Policy and Innovation; Mara D’Amico of ACOG.

In this column for the JAMA Health Forum, Larry Levitt highlights four changes implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic that helped to make health care more accessible and affordable and the prospects for those changes to telehealth, COVID-19 coverage, Medicaid and marketplace premiums continuing beyond the pandemic’s end.

Health insurers are now submitting to state regulators proposed 2023 premiums for plans offered on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces. Changes in these unsubsidized premiums attract a lot of attention, but what really matters most to the people buying coverage is how much they pay out of their own pockets. And the amount ACA Marketplace enrollees pay is largely determined by the size of their premium tax credit. Generally speaking, when unsubsidized premiums rise, so do the premium tax credits, meaning out-of-pocket premium payments hold mostly steady for people getting financial assistance. (more…)

Health insurers are now submitting to state regulators proposed 2023 premiums for plans offered on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces. Changes in these unsubsidized premiums attract a lot of attention, but what really matters most to the people buying coverage is how much they pay out of their own pockets. And the amount ACA Marketplace enrollees pay is largely determined by the size of their premium tax credit. Generally speaking, when unsubsidized premiums rise, so do the premium tax credits, meaning out-of-pocket premium payments hold mostly steady for people getting financial assistance. (more…)

Health insurers are now submitting to state regulators proposed 2023 premiums for plans offered on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Marketplaces. Changes in these unsubsidized premiums attract a lot of attention, but what really matters most to the people buying coverage is how much they pay out of their own pockets. And the amount ACA Marketplace enrollees pay is largely determined by the size of their premium tax credit. Generally speaking, when unsubsidized premiums rise, so do the premium tax credits, meaning out-of-pocket premium payments hold mostly steady for people getting financial assistance. (more…)

If the Supreme Court overturns Roe v Wade, the landmark decision that established the right to abortion, then individual states can regulate abortion without any federal requirement to protect abortion access. While about half of the states in the U.S. will move to either ban or highly restrict abortion access for their residents, there is growing momentum in a handful of states to not only protect abortion access for their state residents, but also to expand access to people who live in states that ban or restrict abortion. A new KFF brief takes a closer look at the policies and laws states have enacted to protect abortion access.

Actions states have taken range from clarifying and strengthening their long-standing protections for abortion rights to enacting policies that seek to assure affordable access to abortion services and to protect clinicians in their states from criminal charges and civil liability if they perform abortions.

Some states, like California, Maryland, Washington, and Delaware, are finding ways to expand the pool of clinicians qualified to provide an abortion. In New Jersey, the governor signed a statutory protection for abortion. Connecticut has enacted legislation to protect clinicians who provide abortion care from out of state civil and criminal penalties. Maryland and California recently passed laws requiring most insurance providers to cover the cost of an abortion, with no cost-sharing.

While these approaches may improve access to abortions for some, many people living in states with an abortion ban, particularly those that are low-income, will experience access challenges and may not be able to get to a neighboring state to obtain an abortion, regardless of increased protections and availability offered by neighboring states.

For more information on abortion, including a new Policy Watch on employer coverage of travel costs for out-of-state abortions, visit the KFF Women’s Health page.

A growing number of states are passing laws restricting access to abortion ahead of the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Dobbs v. Jackson case. Should the Court overturn Roe v. Wade and eliminate the federal standard regarding abortion access, states would set their own standards, banning or protecting abortion access. As employers come to terms with the fact that their workers may not be able to get abortion services where they live, some have begun taking action to support access to abortion for their workers or dependents who live in states that would ban it. In addition to the cost of abortion care, some people may be faced with travel expenses, which could present a sizeable financial barrier, particularly for lower-wage workers. There has been recent attention to employer actions to pay the travel costs for workers who need to go out of state to obtain an abortion, but its utility will depend on how the benefit is administered.

Many large employer plans already cover workers’ travel expenses for certain out-of-state health care procedures. This benefit is typically offered to reduce health costs, and for only specific expensive procedures such as hip and knee replacements, via partnerships with large health systems.

However, this benefit differs in intent from corporate actions making headlines lately, where companies are publicly announcing that they will cover travel expenses for workers who need to travel out-of-state travel for abortion if it is banned where they live. Yelp, Citigroup, Apple, Microsoft, and Amazon are among the growing number of large companies that have announced this benefit. It is worth noting that it is not clear from public information what level of coverage their health insurance plans provide for abortion services in- or out-of-network or whether their provider networks even include clinicians who provide abortion care. Some employers had already been covering travel costs for workers to access certain health care services that are not available in their home state, including abortion, and there are likely others who are newly adding this benefit more privately.

Workers seeking an abortion in states with restrictive abortion laws may have to travel to another state with fewer restrictions. In addition to the cost of the abortion, which costs almost $600 for the majority of self-pay, first trimester abortions, these individuals may face travel expenses that could add up to hundreds or even thousands of dollars, depending on how far they must travel. The Federal Reserve Board found over 35% of U.S. adults do not have enough in savings or cash equivalent to pay for a $400 emergency expense, meaning that for many individuals, these costs can be prohibitively expensive. For employers with a large lower-wage workforce, this could be an especially meaningful benefit, as many would lack the resources to afford airfare, gas, lodging, and other travel-related expenses. While most of the large companies that have announced these travel benefits have a substantial higher-wage workforce who are more likely to be able to absorb travel costs without additional financial support, some companies have pledged to make this benefit available to hourly and retail workers, who tend to be lower-wage.

Many employers who offer this benefit do so through their health insurance plans. Including this benefit as part of the health plan might help mitigate some worker privacy concerns since health insurance plans and employer-sponsored self-funded plans are subject to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), the federal privacy law. However, privacy protections may have limitations, and employers involved in administering the health plan might still have access to the information. Also, this approach may not extend to workers who would most benefit because part-time and hourly workers may not be eligible for the employer’s health insurance plan, and lower-wage workers may be enrolled in Medicaid or ACA Marketplace plans instead.

Other employers have set up a separate fund outside of their health insurance plan that workers access via their human resources department. However, workers may not be comfortable disclosing to their employer that they are seeking an abortion out of concern for confidentiality or possible discrimination. The federal Pregnancy Discrimination Act, Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 (FMLA), as well as some state laws, may protect workers from discrimination or retaliation by their employer with regard to accessing an abortion more broadly. In addition, abortion is still highly stigmatized, and workers may not want their employers to know that they have used or applied for this travel benefit. How employers are structuring this travel benefit outside of the health plan – including whether it would be taxable for workers — is unclear.

Regardless of whether the employer provides the travel benefit through their health insurance or a separate program, affordability could still be a problem for lower-wage workers if the employer’s program requires workers to pay upfront and get reimbursed for expenses. These costs could be prohibitive for lower-income workers who may not be able to afford the upfront travel costs or have a credit card to charge the expenses.