FAQs on Health Spending, the Federal Budget, and Budget Enforcement Tools

Note: This brief was updated on March 20, 2023, to include details on fiscal year 2023 spending from the fiscal year 2024 budget released by the Biden Administration on March 9, 2023.

In January 2023, Treasury Secretary Yellen announced that the U.S. had reached the $31.381 trillion debt limit, prompting the Treasury Department to begin taking so-called “extraordinary measures” that are expected to help the government avoid defaulting on its debt until the summer of 2023. The debt limit, also known as the debt ceiling, is the maximum amount of money that the federal government is legally authorized to borrow to cover federal spending, including Social Security, Medicare, defense, and other federal government programs and obligations. The amount of the debt limit is established by law and increasing or suspending it requires legislative action. Congress has passed legislation 20 times since 2001 to increase or suspend the debt limit to avoid the federal government defaulting on its obligations.

In current discussions around the debt limit, some Republican lawmakers have pushed for reductions in future federal spending as part of a deal to raise the debt limit. The Biden Administration has said it will not negotiate spending reductions as part of debt limit talks but is open to separate discussions about approaches to debt and deficit reduction. House Speaker McCarthy has agreed that cuts to Social Security and Medicare are “off the table” in these discussions but has not ruled out seeking other spending cuts. This leaves open the question of whether Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) premium tax credits, and possibly other health programs and services could be targeted for spending reductions in the near future.

These FAQs answer basic questions about health spending and the federal budget and budget enforcement tools, including the debt limit and sequestration. Health spending includes mandatory spending on health insurance programs like Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the ACA Marketplaces; and discretionary spending on federal agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA. Discretionary spending also includes domestic health programs and services, such as hospital and medical care for veterans, and the Indian Health Service; and spending for global health programs and services, such as the U.S. President’s Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). (See the Methods box for details on the data used for this analysis.)

How much support does the federal government provide for health programs and services?

The federal government provides support for health programs and services both through spending on programs and services and through tax expenditures. Federal spending on domestic and global health programs and services accounted for 29% of net federal outlays in fiscal year (FY) 2023 (taking into account offsetting receipts), or $1.9 trillion out of $6.4 trillion (Figure 1). Specifically, Medicare accounted for 13% of the total, Medicaid and CHIP accounted for 10%, other domestic health spending accounted for 4%, hospital and medical care for veterans was 2%, and global health was 0.1%. By comparison, Social Security accounted for 21% of federal outlays in FY 2023, while defense accounted for 13%.

Mandatory spending comprises the majority (88% or $1.6 trillion) of federal spending on health programs and services. Mandatory spending is not subject to annual appropriations votes by Congress but instead mandated by existing laws. Mandatory health spending includes nearly all Medicare spending, federal spending on Medicaid and CHIP (which are jointly funded by states and the federal government), and the refundable portion of the health insurance premium tax credit for coverage through the ACA Marketplaces, along with other mandatory health spending, which is detailed in Table 1. Medicare alone, which covers 65 million older adults and younger people with long-term disabilities, accounts for half of mandatory spending on federal health programs and services, while Medicaid, which covers 84 million individuals, accounts for another 37% (Figure 2). ACA premium tax credits—which include a refundable portion that counts as outlays and a non-refundable portion that counts as lost revenue—represent a much smaller portion (5% of mandatory outlays).

The remaining 12% of federal health spending ($231 billion) is discretionary spending, which is subject to votes by Congress during the annual appropriations process. Discretionary health spending includes nearly all spending on veterans’ hospital and medical care, estimated to provide services to more than 7 million veteran patients in FY 2022; spending on agencies such as the CDC, NIH, FDA, and HRSA; global health spending; and certain other health programs and services (Figure 3, Table 2).

In addition to federal spending on health programs and services, the federal government provides several tax benefits that support health-related activities, known as tax expenditures. These tax provisions are similar to federal spending in that they provide benefits from the federal government to employers, individuals, and other entities. Tax expenditures are revenue losses to the federal government because they allow for certain exclusions, exemptions, or deductions from income for the purpose of determining the amount of income taxes owed; provide preferential tax rates for certain programs; or reduce tax liability through tax credits.

Based on data from the Treasury Department, the three largest health-related tax expenditures in FY 2022 were:

- the tax exemption of employer contributions for medical insurance premiums and medical care: $224.5 billion (not including additional lost revenue from exempting employer contributions from payroll taxes for Social Security and Medicare);

- the premium tax credit for ACA Marketplace coverage: $14.7 billion (excluding the value of the refundable portion of the tax credit, which is classified as a mandatory outlay); and

- tax deductions for contributions to Medical Savings Accounts and Health Savings Accounts: $13 billion.

How does the debt limit affect federal health spending?

The debt limit itself does not directly affect levels of spending by the federal government, including mandatory and discretionary health spending. Government spending and revenues are, however, directly affected by legislation passed by Congress and signed by the President, which can add to the federal deficit and debt if, on balance, spending exceeds revenue. Over time, budget deficits have added to the government’s borrowing needs. Based on the latest projections from the Congressional Budget Office, annual federal budget deficits, amounting to a cumulative $20.2 trillion over the coming decade, will result in a substantial increase in federal debt.

Raising the debt limit does not mean the federal government is allowed to spend more money than Congress has previously authorized it to spend. But in a scenario where Congress failed to raise the debt limit, the government would be unable to borrow more money and would have insufficient funds to meet its current obligations. The amount of allowable spending would be limited to cash on hand and incoming revenues.

If the debt limit were reached and the Treasury Department had taken all “extraordinary measures” to avoid default, it is not clear what steps the government would or could take in response to meet the government’s obligations, but could include payment delays, prioritizing some payments over others, and automatic across-the-board payment reductions. Any of these options could affect payments for health and retirement benefits, including Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and CHIP, veterans’ benefits, and other programs.

How does the regular congressional budget process affect federal health spending?

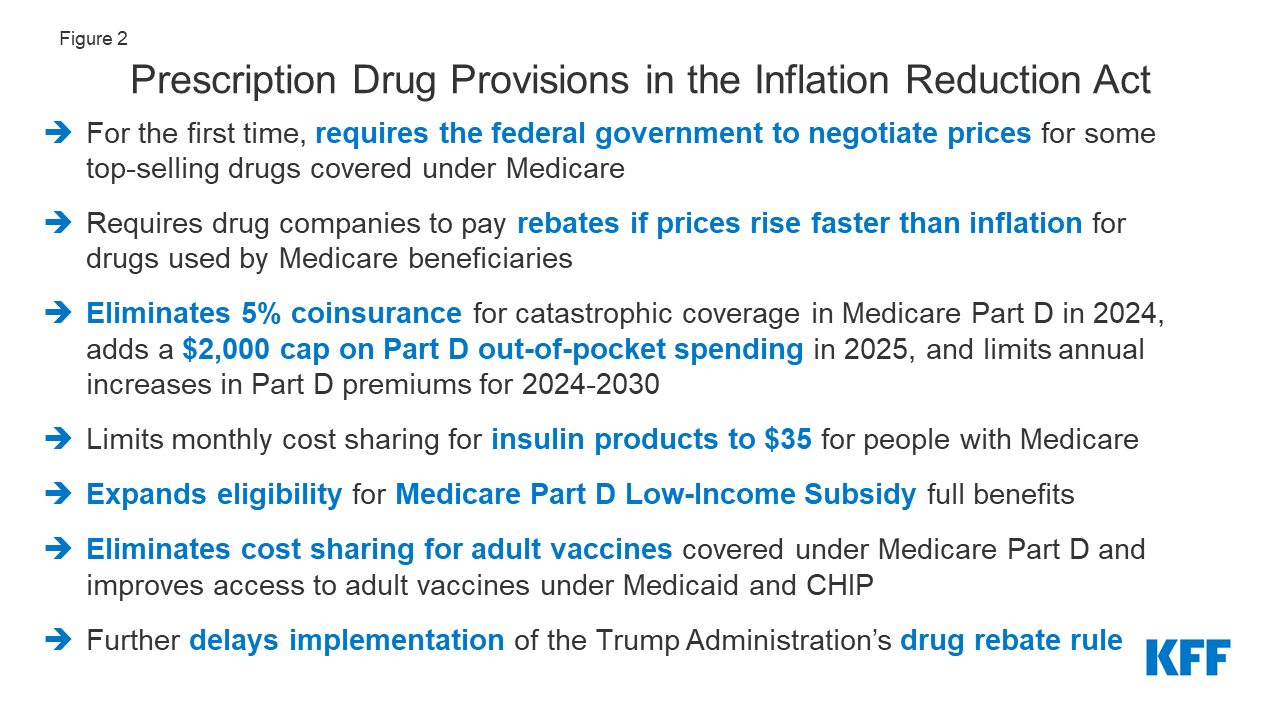

The regular Congressional budget process begins with a concurrent resolution that sets the overall federal spending and revenue levels. The budget resolution may also include reconciliation instructions to allow for a fast-track process that requires only a majority vote in the Senate for changes to spending on mandatory programs and federal revenues. The reconciliation process has recently been used to pass the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, as well as portions of the Affordable Care Act of 2010.

In most years over the last two decades, however, Congress has failed to agree to a budget resolution. When a resolution is not adopted, each chamber adopts its own (and usually different) targets for discretionary spending, and changes to mandatory spending and revenues may only be done through regular order (rather than reconciliation), and thus typically require a three-fifths vote in the Senate.

The Appropriations Committees develop 12 separate appropriates measures, including the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies appropriations bill, which includes most domestic discretionary health spending. These bills are often combined for consideration by the full House and Senate into an omnibus bill. Congress is required to approve appropriations and the President is required to sign them into law before September 30 (the end of the federal fiscal year). If this deadline isn’t met, Congress can pass a continuing resolution to fund the government based on the preceding fiscal year amounts. When neither full year appropriations nor a continuing resolution is passed, the government “shuts down.” Continuing resolutions are more common than government shutdowns. For example, before approving the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, which funds the government through September 30, 2023, Congress passed two continuing resolutions as lawmakers negotiated.

In years that a budget resolution is agreed to, it may also include rules designed to impose fiscal discipline on the legislative process. These rules remain in effect until removed or revised by a future resolution. Two examples include the House and Senate PAYGO rules, which require any legislative provisions that are projected to increase the deficit over various time periods (different under House and Senate PAYGO rules) to be offset by spending reductions or tax increases. The rules are enforced through a “point-of-order” against legislation that violates the rule, though these are routinely waived when the legislation has sufficient support in the chamber.

What is sequestration and how does it affect federal health spending?

Sequestration is a budget enforcement tool that requires automatic, across-the-board reductions in federal spending, typically by a specified percentage. The sequestration process was established by Congress in 1985 to encourage Congress to meet specific budgetary goals. It is of recent interest because of the budget sequesters called for under the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) and the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 (PAYGO).

The BCA was enacted over a decade ago during a time when many lawmakers were expressing concern over federal budget deficits. The law included limits on annual discretionary spending, established a committee to develop proposals to reduce the deficit, and required sequestration of mandatory spending and further reductions in discretionary spending if the committee failed to report deficit reduction legislation. Because the committee did not come to agreement, sequestration was triggered. Under the BCA, a sequestration of mandatory federal spending was established for FY 2013 to FY 2021 but has been extended several times and is currently in effect through FY 2031. (The separate BCA requirement for limits on discretionary spending expired at the end of FY 2021.)

Under the Statutory PAYGO Act, sequestration is triggered when legislation enacted by Congress during a session is projected to increase the deficit on average over a five- or ten-year period, as determined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). However, sequestration under Statutory PAYGO has not yet occurred since it has been waived by Congress each time it would otherwise have been required.

Certain programs and types of spending are exempt from sequestration. Most of these exemptions relate to mandatory spending. Health spending exempt from sequestration includes certain health programs such as Medicaid, CHIP, ACA tax credits, Medicare Part D Low-Income Subsidies, Medicare Part D reinsurance spending, and veterans’ medical care. Social Security is also exempted.

Notably, most Medicare spending is not exempt from sequestration, but for Medicare (as well as certain other programs), special rules apply that limit the percentage reduction in spending. Under the BCA, reductions in Medicare benefits spending—including payments to providers under Part A and Part B and payments to plans under Part C (Medicare Advantage) and Part D—are limited to 2% rather than the uniform percentage reduction that would be applied to other nonexempt mandatory spending. Under a Statutory PAYGO sequester, Medicare benefit payment reductions are limited to 4%.

Sequestration of Medicare spending is currently in effect under the BCA’s mandatory spending sequester, although during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was suspended from May 2021 to March 2022 and reduced from 2% to 1% from April 2022 through June 2022. The Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), 2023 extended the BCA’s 2% sequestration of Medicare spending specifically partway into FY 2032 rather than expiring at the end of FY 2031, as it does for other nonexempt mandatory spending. In addition, while enactment of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 triggered a 4% Medicare sequester under Statutory PAYGO for FY 2022 (along with across-the-board cuts in certain other mandatory spending), Congress delayed these cuts to January 1, 2023 and then waived them for 2023 and 2024.

Health Spending and Budget Issues to Watch

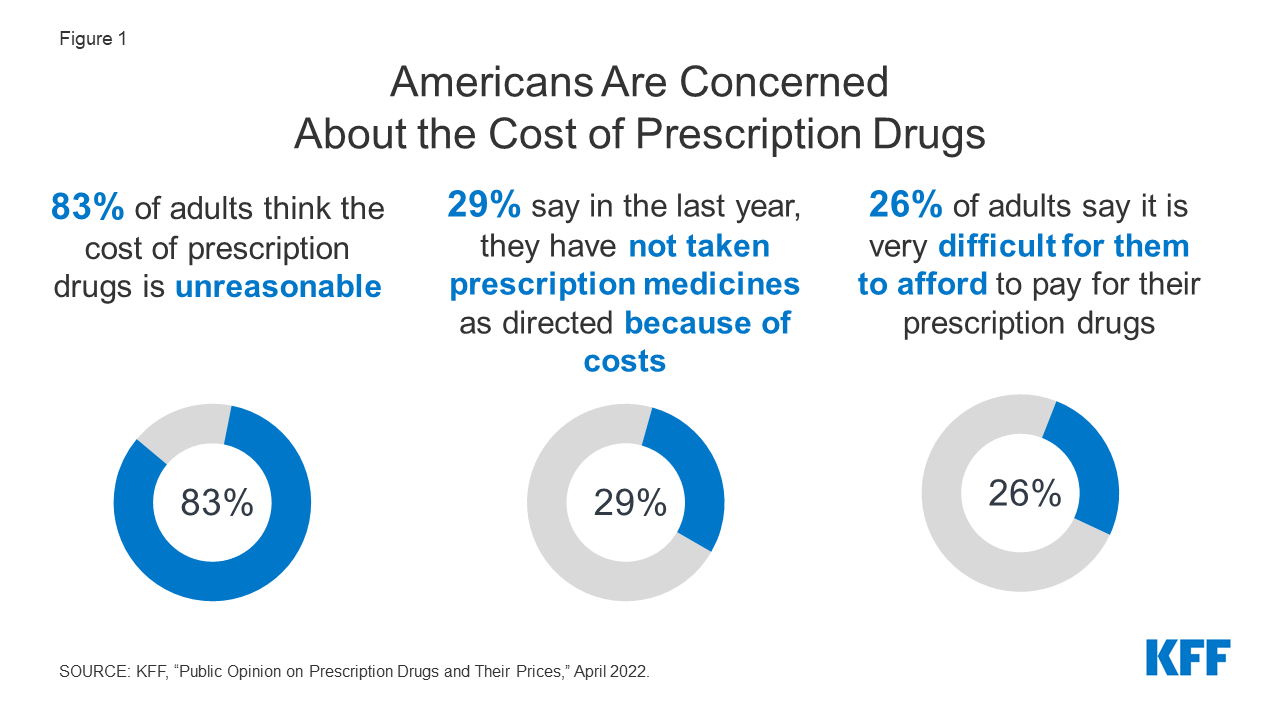

The Biden Administration has released the President’s budget for FY 2024, which includes many savings and revenue proposals to reduce the federal deficit, along with many health-related proposals to lower prescription drug costs, extend the solvency of the Medicare Part A trust fund, and make permanent the ACA’s enhanced premiums tax credits, among other proposals. Under regular order, release of the President’s budget would be followed by the passage of a budget resolution by Congress in April. These actions could set the stage for discussions over the federal budget deficit and debt between the Administration and members of Congress in subsequent months. House Republicans have expressed support for a plan to balance the budget within 10 years by cutting government spending (and not increasing taxes). But without new revenues and without reducing spending on Social Security, Medicare, or defense, steep spending reductions in other areas would be needed to balance the budget. This could mean large spending cuts to health programs and services such as Medicaid, CHIP, and ACA subsidies, as well as veterans’ hospital and medical care, the NIH, FDA, and other health agencies, and other health programs and services.

The Treasury Department estimates that it will have exhausted the extraordinary measures being taken to avoid a default on the debt by early June. The Biden Administration supports a so-called ‘clean’ vote on raising the debt limit, separate from any discussions about approaches to reduce the federal deficit and debt. Although President Biden and Speaker McCarthy have ruled out changes to Medicare spending in discussions over the debt limit, it is possible that cuts to other federal health spending programs and services could be considered. Policymakers who are seeking to negotiate reductions in federal spending in exchange for a vote to raise the debt limit have proposed limiting new discretionary spending, which would affect many federally funded health programs and services, and imposing work requirements for Medicaid, among other options.

While most policymakers have not expressed support for cuts to Medicare in current budget discussions, CBO projects that higher spending on both Medicare and Social Security will put growing pressure on the federal budget. Federal law requires annual reports on the financial status of the Medicare and Social Security trust funds to be issued by April 1 each year, and typically these reports draw attention to this issue. Based on the 2022 report, the Medicare Trustees projected that the Medicare Part A trust fund, which pays for inpatient hospital, skilled nursing facility, home health and other Part A services, would be depleted in 2028. The projected shortfall is attributable to both the rise in spending, due to rising health care costs, growing enrollment, and an aging population, combined with insufficient revenues to cover all expenditures.

Some policymakers in Congress have proposed the creation of bipartisan, bicameral committees to address the solvency of government programs with trust funds, including Medicare, Social Security, and the highway trust fund. The President’s FY 2024 budget proposes to generate new tax revenue for the Part A trust fund through tax increases on high-income taxpayers (households earning more than $400,000 per year). These additional revenues, together with savings from prescription drug proposals, which would be credited to the Part A trust fund, are estimated to extend the solvency of the Medicare Part A trust fund by at least 25 years.

In the near term, the question of how lawmakers will respond to the debt limit looms large in current discussions about the federal budget and federal spending on government programs such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The government has been funded through the end of the current fiscal year (September 30, 2023), but action will be needed by then to avoid funding gaps and avert a government shutdown, which could have the effect of curtailing the operations of government agencies like the FDA, NIH, and CDC and the provision of certain veterans’ services. Over the longer term, public and private payers and individuals face financial pressures associated with higher health care costs. For the federal government, rising health care costs affect spending on the government’s major health care programs, Medicare and Medicaid, along with spending on certain other health programs and services, such as veterans’ medical care. Providing funding for both mandatory and discretionary health programs and services that millions of people rely on while taking steps to address the growing federal budget deficit and debt could pose a challenge for policymakers in the months and years ahead.

This work was supported in part by Arnold Ventures. KFF maintains full editorial control over all of its policy analysis, polling, and journalism activities.

Methods

This analysis is based on data on federal outlays from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) FY 2024 President’s Budget. Specifically, we use FY 2023 data on federal outlays from Table 24-1. Budget Authority and Outlays by Budget Function, Category, and Program.

The federal budget groups spending into roughly 20 categories called ‘budget functions,’ which are groups of activities or programs that fulfill specific purposes, such as defense, transportation, and health. This analysis focuses on non-defense health spending, which is defined to include spending in the following categories within four budget functions:

150: International Affairs:

151: International development and humanitarian assistance: Global health

550: Health:

551: Health care services

552: Health research and training

554: Consumer and occupational health and safety

570: Medicare

700: Veterans Benefits and Services

703: Hospital and medical care for veterans

For each category, we include both mandatory and discretionary spending, where applicable.

Spending totals in this analysis are outlays, which represent actual cash flows, rather than budget authority, which represents the amounts authorized by Congress for new obligations by federal agencies. Global health outlay totals presented here do not match those presented in other KFF resources, such as the U.S. Global Health Budget Tracker, which highlight the budget authority totals as provided by Congress in annual appropriations and include some other funding components that are counted elsewhere in this analysis. As noted above, in this analysis ‘global health’ is a category of spending within budget function 151: International development and assistance, which accounts for the majority of global health funding. Additional global health funding at NIH and CDC is included under budget function 550: Health.

This analysis does not include spending by the Department of Health and Human Services that falls outside of the ‘Health’ or ‘Medicare’ budget functions, which consists mainly of spending on the Administration for Community Living (ACL) and Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which falls within budget function 500—Education, Training, Employment, and Social Services.