People who use home- and community-based services (HCBS) are at heightened risk of serious illness or death from exposure to COVID-19 and disproportionately likely to need hospital or nursing facility care if HCBS are unavailable. However, during the pandemic, there were fewer workers available and willing to provide services and extra safety precautions were required to prevent COVID-19 infection. Recognizing those challenges, the federal government provided states with new authorities to maintain access to HCBS during the public health emergency (PHE). The PHE has been in place since 2020 and will end on May 11, 2023. This policy watch explores the potential implications of ending the PHE for Medicaid HCBS programs, including new or continued workforce challenges and potential reductions in patients’ access to care.

In 2020, an estimated 6 million people used HCBS according to CBO estimates. HCBS are provided in peoples’ homes and other non-institutional settings. They include medical and supportive services that assist people with the activities of daily living (such as eating, bathing, and dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (such as preparing meals, managing medications, and housekeeping). They are provided to people who need such services because of aging, chronic illness, or disability and may include personal care, adult daycare, home health aide services, transportation, and supported employment. Medicare generally does not cover HCBS and in 2020, Medicaid spent $162 billion on HCBS—a majority of the $245 billion in total HCBS spending. Although all states offer some HCBS through Medicaid, most services are optional for states, and states may cover different services for different types of Medicaid enrollees. To be eligible for Medicaid HCBS, individuals must have limited financial resources and significant functional impairments.

How Did States Support Medicaid HCBS During the PHE?

States used several types of authorities when responding to the COVID-19 PHE, including disaster-relief state plan amendments, 1115 waivers, and Appendix K changes to 1915c waivers. When the PHE ends on May 11, 2023, changes made through a disaster-relief state plan amendment or 1115 waiver will also end. Changes made using the Appendix K authority will expire within 6 months of the PHE ending (December 11, 2023). With 437 changes to HCBS programs made under Appendix K, it was the most widely used authority. Examples of Appendix K uses include changing processes for determining eligibility, authorizing services, and paying providers; expanding provider qualifications or which providers are eligible to be paid; and expanding the service delivery models. Some changes have ended already, others have been transitioned to permanent authorities, and some will end between May and November 2023 if not also transitioned.

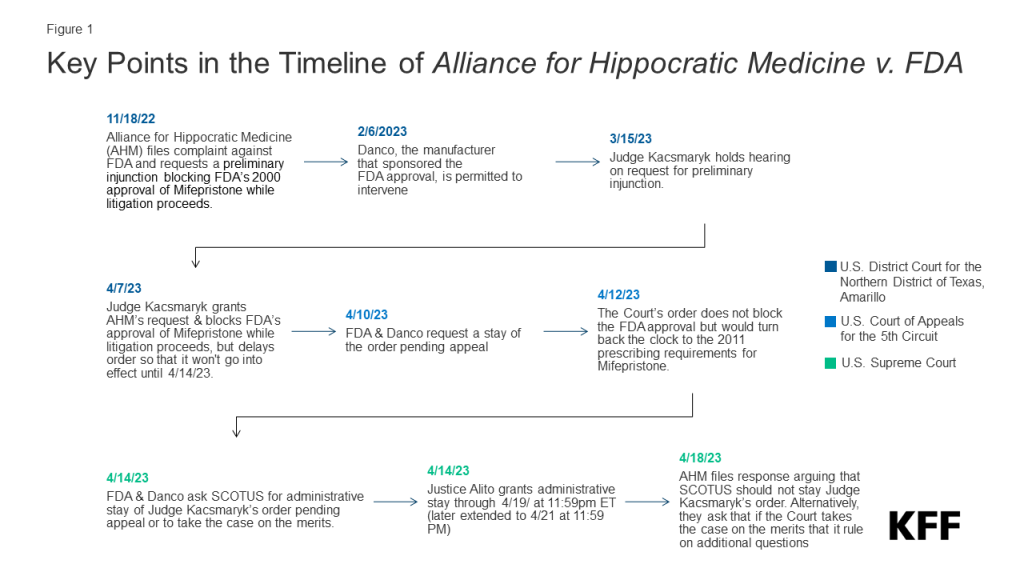

In a survey of states on Medicaid HCBS in 2022, many states reported using PHE authorities to bolster their HCBS programs by expanding eligibility and services and addressing workforce challenges (Figure 1). Within the category of eligibility and enrollment, nearly all states reported making it easier for people to access HCBS through virtual evaluations (49 states), 10 states reported increasing the number of waiver slots, and 5 states reported increasing eligibility limits. In terms of services, the most common change was providing HCBS via telehealth (47 states), followed by increasing utilization limits (37 states). Half of the states added new HCBS and around a quarter removed prior authorization requirements.

Many states reported that they planned to continue the PHE policies after the authority expires, but in other cases, states expect the policies will end or have not yet decided. Fewer than half of states that allowed virtual evaluations reported plans to continue doing so after the PHE ends, and eligibility levels will return to their pre-pandemic levels in at least four of the five states with higher limits. Most states reported that they plan to continue providing HCBS via telehealth, but prior authorization and utilization limits may return to pre-pandemic levels in half or more of states that had made changes.

During the PHE, most states (39) reported responding to workforce challenges by allowing family caregivers to be paid, but only 20 states plan to continue that policy after the PHE ends (Figure 2). In a 2022 survey, states reported that maintaining a workforce was the biggest challenge for HCBS programs and the primary effect of COVID-19 on HCBS programs was to amplify existing workforce shortages. Recent analysis on the Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker shows that, as of October 2022, the number of workers providing long-term services and supports was measurably lower than in early 2020. Allowing family caregivers to be paid providers was an important tool in responding to shortages of HCBS workers stemming from the pandemic, but this authority will be ending in many states—even as workforce shortages persist.

Most states provide HCBS through “waiver” programs that allow them to limit eligibility and, in many cases, to people with certain types of health conditions. In a 2022 survey of states, the most frequently reported waivers were those serving people with intellectual or development disabilities (47 states), and of those, 28 states allowed family caregivers to be paid providers. When the PHE ends, 14 states will continue the policy, but 8 states are planning to end it, and the outcome is undecided in 6 states. The second most reported waivers were for adults ages 65 and older or with physical disabilities (42 states), and of those, 28 states allowed family caregivers to be paid providers. That policy will continue in 11 states, end in 8 states, and is unknown in 9 states.

What to Watch in Medicaid HCBS as the PHE Ends?

Looking ahead, the loss of PHE flexibilities could further exacerbate workforce challenges for HCBS programs. Many elements of life have started to return to pre-pandemic norms, but Medicaid HCBS programs continue to face major workforce challenges. Loss of the PHE flexibilities—and in many states, the end of paying family caregivers—may further exacerbate those challenges. Some challenges may be addressed, in part, with HCBS funding from the American Rescue Plan Act, which states may spend until March 31, 2025. A recent analysis of states’ spending plans for those funds found that 32 states were increasing payment rates for HCBS providers, 39 were funding provider training and certifications, and many states were engaging in other activities that could help bolster the HCBS workforce.

Unwinding the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision may create additional challenges for people who use HCBS. Between February 2020 and March 2023, states received enhanced federal funding for Medicaid in exchange for keeping people continuously enrolled in Medicaid. States were able to resume disenrollments starting April 1, 2023 and the enhanced federal funding will phase down through December 2023 if certain conditions are met. During the unwinding, some people who use HCBS could lose their Medicaid eligibility—either because they are no longer eligible or because they face administrative barriers to complete renewals. The phasing-out of enhanced federal funding could create state budget pressure and result in fewer resources for optional services such as HCBS in response.

Longer-term it is unclear whether more significant changes for HCBS are possible, including potential changes that would attempt to reduce or eliminate HCBS waiting lists. On April 18, the White House issued a statement summarizing a series of executive actions that include provisions aimed at strengthening the HCBS workforce. Those provisions include enhancing job quality for people who provide Medicaid HCBS, providing support for family caregivers of people with dementia through Medicare, and supporting HCBS workers who want to further professionalize or join a union. The president’s budget has called for an additional $150 billion in funding for Medicaid HCBS and there are legislative proposals that would increase federal funding for HCBS. However, proposals to increase federal funding for Medicaid HCBS face long odds in a divided Congress. There are competing proposals to significantly reduce the federal government’s spending on Medicaid, though those are unlikely to gain support of the White House or Democrats in the Senate. At the same time, states face pressure to provide HCBS to the growing number of people who need long-term services and supports and wish to receive them in their homes.