Behavioral Health Crisis Response: Findings from a Survey of State Medicaid Programs

Recent efforts to develop and improve behavioral health crisis response systems have been marked by several key federal initiatives. These include national guidelines for crisis care put forth by SAMHSA in 2020, an initiative for states to use Medicaid funding for mobile crisis services through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in 2021, and the 988 crisis line rollout in 2022. Most recently, the Consolidated Appropriations Act–passed in December 2022– included several provisions aimed at enhancing and evaluating the behavioral health crisis continuum. This surge in action has grown in light of longstanding and worsening behavioral health issues, tragic incidents involving law enforcement, and growing reports of psychiatric boarding in emergency departments (EDs).

Medicaid – the single largest payer of behavioral health services in the country – is particularly well positioned to partner with state behavioral health authorities and other stakeholders to plan, implement, and monitor the behavioral health crisis response systems. Further, the Medicaid population may be particularly impacted by these changes, as 39% have mild, moderate, or severe mental health or substance use disorder conditions.

To better understand the development, implementation, and coverage of crisis services in state Medicaid programs, KFF conducted a Behavioral Health Survey of state Medicaid programs as a supplement to its 22nd annual budget survey of Medicaid officials conducted by KFF and Health Management Associates (HMA). We surveyed state Medicaid officials about the services that were in place in state fiscal year (FY) 2022 or implemented/planned for FY 2023, as well as challenges they face. Forty-four states (including the District of Columbia) responded to the survey, although response rates varied by question. This issue brief utilizes this survey data to answer three key questions:

- What are the core behavioral health crisis services and how often are they covered by states?

- Are states pursuing opportunities for enhanced federal funding for crisis services?

- What challenges are confronting Medicaid programs in the implementation and delivery of crisis services?

Background

Crisis behavioral health services provide access to trained mental health professionals for individuals experiencing mental health or substance use emergencies–an alternative to emergency departments and law enforcement. Literature has shown that crisis services divert people away from psychiatric hospitalization and reduce the need for intervention within emergency departments or by law enforcement. It is estimated that law enforcement officers spend a sizable amount of their time responding to behavioral health calls, while ED visits for behavioral health reasons continue to rise; however, professionals in these settings are generally not equipped to treat mental health conditions or safely de-escalate crises. Without access to necessary evidence-based care, mental health crises can worsen or prolong.

National guidelines identify three core crisis services that should be accessible to anyone who is experiencing a behavioral health crisis: crisis hotlines, mobile crisis units, and crisis stabilization. While crisis residential and crisis respite services are a part of the crisis continuum and may also provide interventions to help to stabilize crisis, they are not considered core services. Although these crisis services do not necessarily have to be accessed in a specific order, Crisis Now illustrates how they may be accessed and used. Core crisis services are described below in Table 1:

SAMHSA’s national guidelines report that integration of services across systems will reduce fragmentation and improve care transitions. Examples of technology and integration that may help include a system for assessing crisis levels, a crisis bed registry, GPS mobile crisis dispatch, and the ability for crisis staff to schedule appointments. Further, data dashboards may provide ongoing insights into service utilization and impact of crisis services.

Medicaid Coverage of Core Crisis Services

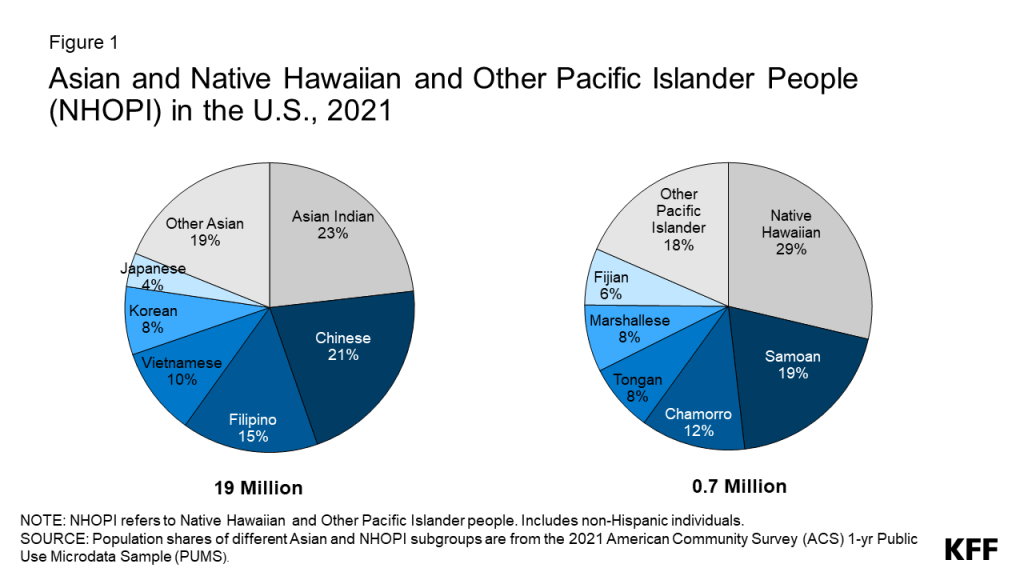

About three-quarters of responding states (33 of 45) do not cover all three core crisis services for FFS adults, but most states cover at least one core crisis service (41 of 45) (Figure 1). Medicaid programs are less likely to cover crisis services compared to other behavioral health service categories. Despite this generally lower coverage, the landscape of crisis response systems is evolving across states, driven in part by the opportunity for enhanced federal matching funds for qualified mobile crisis services (see next section of this brief). For example, Massachusetts is implementing a multi-year roadmap for behavioral health reform that includes a 24/7 help line, clinical assessment, and referral to treatment. The state of Montana is working toward aligning its crisis services with the Crisis Now Model. Crisis hotline services are available to anyone free of charge across all states, but some Medicaid programs help to finance crisis hotlines by reimbursing crisis hotline services, which might include 988 or other hotlines.

States report higher coverage rates for mobile crisis and crisis stabilization units but lower coverage for crisis hotlines under adult fee-for-service (FFS) Medicaid. However, it is unclear how widespread these services are within states and whether they align with best practice recommendations, such as trauma-informed care. (These findings do not account for variations in coverage provided by managed care organizations (MCOs) or Section 1115 waivers.)

- Nearly three-quarters of responding states (33 of 45) reported mobile crisis coverage for adults in FFS programs. People experiencing a crisis may receive help from mobile crisis teams, which are usually dispatched from crisis hotlines, providers, emergency medical services, or law enforcement.

- Nearly two-thirds of responding states (28 of 45) report adult FFS coverage of crisis stabilization units. Research suggests that care provided in crisis stabilization facilities may produce cost savings compared to emergency department or inpatient care.

- Crisis hotlines are the least frequently covered core crisis service (22 of 45 responding states). Crisis hotline services are available to anyone free of charge across all states, but some Medicaid programs help to finance crisis hotlines by reimbursing crisis hotline services, which might include 988 or other hotlines. One reason why coverage for this crisis service is lower than others may be the difficulty in obtaining insurance information during emergency crisis calls. Some states are finding ways to address this issue, with the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) reporting that some states are surveying callers about Medicaid coverage and utilizing an administrative federal match based on share of Medicaid-covered callers.

Most of the states that cover mobile crisis also report that they currently require or are planning to require peer supports on their teams. Peer supports are individuals with lived experience, and research and national guidelines support their involvement in mobile crisis teams. A total of 7 states required peer supports on mobile crisis teams as of FY2022, with 13 more states planning to require it in FY2023. Several states report that they encourage peer support, but do not make it mandatory. Other states have plans to include peer supports in subsequent years or on a subset of teams. Arizona, for example, plans to require peer support specialists on 25% of mobile teams in FY 2023.

Options for Enhanced Federal Funding for Crisis Services

Over half of responding states (28 of 44) report that they have taken up or plan to implement the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) mobile crisis intervention services option (Figure 3). The option under ARPA is available to states for 5 years, beginning April 1, 2022. Medicaid programs that provide qualifying community-based mobile crisis services under this option will receive 85% enhanced federal matching funds for the first three years of implementation. This enhanced funding must supplement, not supplant, the previous level of state funding for qualifying mobile crisis services. While it is not necessary for mobile crisis services to be available across the state or to all populations to qualify for enhanced match, states must meet certain criteria, such as 24/7 service among participating providers. Among states that chose to pursue the ARPA option, 8 states reported implementation of qualifying mobile crisis services in FY 2022; 11 states reported plans to implement in FY 2023; and 9 in FY 2024 (Figure 3). Among states without plans to implement ARPA mobile crisis services or with an undetermined status, reasons for not pursuing this option included pre-existing non-ARPA crisis services and/or difficulty understanding and meeting the ARPA requirements for the enhanced match. Through funding provided by the ARPA, planning grants were awarded to 20 state Medicaid programs–to help them prepare for the implementation of qualifying mobile crisis services.

Less than one-quarter of states (8 of 43) are using or plan to access enhanced administrative match to support the technology needed to support implementation of crisis call centers or other crisis services. SAMHSA’s best practice guidelines advocate for an “air traffic control” model for crisis services that includes a system for assessing crisis levels, wait times, and linkage to additional services, as well as the ability for crisis staff to schedule appointments, a crisis bed registry, GPS mobile crisis dispatch, and performance monitoring dashboards. ARPA guidance explains that states can apply a 90% enhanced administrative match for the development of certain technology systems to help implement crisis services (and receive an ongoing 75% match for operations of these systems). Kentucky and Massachusetts are applying these funds toward crisis hotline integration or development, while New Jersey focuses on mobile response teams and vacancy tracking.

Challenges Confronting Medicaid Programs in the Implementation and Delivery of Crisis Services

State Medicaid programs often collaborate with multiple state agencies to design and implement crisis services. To gain a deeper understanding of the barriers associated with the implementation and delivery of these services, we asked state Medicaid programs about the challenges states have faced or anticipate facing. Additionally, we asked them to identify which of these areas posed the most significant obstacles.

Almost all responding states (38 of 44) reported experiencing or expecting at least one obstacle to implementing crisis services, particularly workforce shortages and geography-based challenges (Figure 4). Workforce shortages and geographic challenges are not unique to crisis services, as other areas of behavioral health report similar barriers. Other challenges include provider training needs and scope-of-practice limitations. When we asked states to identify their biggest challenge, they overwhelmingly pointed to the shortage of a qualified workforce as their most significant obstacle.

- Workforce Shortages. Finding qualified mental health professionals willing to work in crisis services and provide around-the-clock care, especially overnight, is a significant challenge. This high-stress environment contributes to high turnover rates, complicating the fulfillment of some ARPA requirements, such as maintaining a 24/7 two-person team. To address these workforce shortages, several states, including Nevada, have implemented strategies like allocating start-up funds to help providers expand their crisis workforce.

- Geographic Challenges. Increased travel times in rural areas can result in longer response times for individuals in need. Some states have considered telehealth as a solution, although limitations exist for those without smartphones, reliable services, or comfort using them. Predicting demand in rural areas is challenging due to less concentrated populations, complicating 24/7 multidisciplinary team staffing. Staff safety is also a concern in areas with poor cell phone or internet reception. Additionally, states with significant tribal populations face added challenges in planning and coordinating efforts across agencies, MCOs, and providers.

- Provider training needs. New and existing crisis professionals typically need initial and ongoing training in crisis services and population-specific topics. States emphasize the importance of providing trauma-informed, developmentally, and culturally appropriate care, which may necessitate additional trainings. States recognize the importance of these trainings, but point out that because of workforce shortages, it is difficult to take the existing crisis workforce out of the field for trainings. States are also challenged by a shortage of available trainings. To address the scarcity of available trainings in its state, Massachusetts is funding a behavioral health training clearinghouse containing free trainings.

- Scope-of-practice limitations. Some states report that the roles and responsibilities of non-licensed staff, such as certified peers, are not always defined by state licensing boards. The shortage of staff and the limited roles they can perform also affect crisis services delivery. For example, in one state, a significant proportion of the workforce is comprised of unlicensed qualified mental health professionals who cannot diagnose or provide assessments for crisis services.

In addition to the challenges specified above, several states provided information about additional challenges:

- Funding. Some states are concerned about sustainability of financing for crisis services, particularly as the ARPA enhanced funding (85% federal match) for community-based mobile crisis services is effective only for the first three years of implementation. For example, Oregon recommends permanent implementation of the enhanced federal match for qualifying crisis services. At present, crisis service financing relies heavily on local and state funding and block grants—though some states have added telecommunication Medicaid is the primary and one of the only insurers reimbursing for these services—even though people with other types of coverage are also served by behavioral health crisis systems. For example, Vermont points out that crisis services should be available to all regardless of insurance and identified the lack of mobile crisis coverage from Medicare and commercial payers as a challenge.

- “Connecting” crisis care and other challenges. States also reported concerns around developing interconnections between 988 and the state’s existing infrastructure for effective “dispatching”, as well as improving cultural awareness and sensitivity to communities.

Looking Ahead

Keeping pace with larger federal and state initiatives, many Medicaid programs are developing or strengthening behavioral health crisis services. 988’s launch and enhanced federal funding opportunities have sparked developments, but states are unsure what will happen when enhanced funding opportunities expire. In addition, workforce shortages, questions about linking and coordinating across systems, and other logistical issues continue to pose challenges both within Medicaid and crisis systems generally.

Recent federal initiatives aim to mitigate some of these challenges. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, passed in December 2022, includes several provisions aimed at enhancing and evaluating the behavioral health crisis continuum. The Act establishes the Behavioral Health Crisis Coordinating Office within SAMHSA, directing it to identify and publish best practices. Additionally, the Act tasks various agencies with producing reports that evaluate the performance measures and outcomes of the behavioral health crisis continuum. Federal investments in the development and implementation of the 988 number have helped Lifeline improve answer rates, even with increases in outreach volume.

Despite recent advances in crisis services, uncertainties persist, including questions of how to integrate services across the crisis continuum and how to secure long-term sustainable funding. According to SAMHSA, crisis systems will be most effective when they can coordinate with each other and connect with other health care areas. The financing of crisis response systems is still emerging, with Medicaid currently a main insurer reimbursing for crisis services. However, Medicaid’s coverage is, at present, less comprehensive for crisis services compared to other categories of behavioral health benefits, though states may continue to enhance this coverage in coming years. As crisis response systems continue to grow and expand, states are navigating a variety of concerns—including workforce shortages, training needs, geographic challenges, and uncertainty about sustainable funding.

If you or someone you know is considering suicide, contact the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988

This brief draws on work done under contract with Health Management Associates (HMA) consultants Angela Bergefurd, Gina Eckart, Kathleen Gifford, Roxanne Kennedy, Gina Lasky, and Lauren Niles.