What is Driving Widening Racial Disparities in Life Expectancy?

Introduction

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, life expectancy in the U.S. declined 2.7 years between 2019 and 2021, from 78.8 years to 76.1 years, marking the largest two-year decline in life expectancy since the 1920’s. This decline further widened the existing gap in life expectancy between the U.S. and other comparably large and wealthy countries. It also exacerbated longstanding racial disparities in life expectancy and mortality within the U.S., contributing to excess deaths and increased costs. This analysis examines trends in life expectancy and leading causes of death by race and ethnicity and discusses the factors that contribute to racial disparities in life expectancy. In sum, it finds:

- There was a sharp drop-off in life expectancy between 2019 and 2021, with particularly large declines among some groups. American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) people experienced the largest decline in life expectancy of 6.6 years during this time, followed by Hispanic and Black people (4.2 and 4.0 years, respectively).

- Reflecting these declines, provisional data for 2021 show that life expectancy was lowest for AIAN people at 65.2 years, followed by Black people, whose expectancy was 70.8 years, compared with 76.4 years for White people and 77.7 years for Hispanic people. It was highest for Asian people at 83.5 years. Data were not reported for Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander (NHOPI) people.

- These declines were largely due to COVID-19 deaths and reflect the disproportionate burden of excess deaths, including premature excess deaths (before age 75), among people of color during the pandemic. Although COVID-19 mortality was a primary contributor to the recent decrease in life expectancy across groups, leading causes of death vary by race and ethnicity.

These recent stark declines and widening racial disparities in life expectancy amplify the importance of addressing underlying drivers of these disparities, including inequities in health insurance coverage and access to care and social and economic factors that drive health.

Trends in Life Expectancy by Race/Ethnicity

Life expectancy at birth represents the average number of years a group of infants would live if they were to experience throughout life the age-specific death rates prevailing during a specified period. Life expectancy is one of the most used measures of population health, enabling comparisons in health status between countries, states, local communities, and demographic groups. Differences in life expectancy occur across a broad range of dimensions which often intersect with each other, including race, socioeconomic status, gender, geography, and other characteristics. For example, In the U.S. and all other comparable countries, men tend to have shorter life expectancy at birth than women. In 2021, life expectancy for women in the U.S. was 5.9 years higher than for men (79.1 years vs. 73.2 year, respectively), and similar gender disparities persisted within racial and ethnic groups. This analysis focuses on differences in life expectancy by race and ethnicity overall, but within racial and ethnic groups there is variation by these other factors, such as gender.

Prior to 2015, there were relatively steady increases in life expectancy in the U.S., but racial disparities persisted. Before 2015, life expectancy in the U.S. steadily increased with an overall gain of about 10 years between 1960 and 2015 from 69.7 years to 79.4 years. While there have been large gains in life expectancy across racial and ethnic groups, racial disparities have been longstanding and persisted over time. Black people have consistently had lower life expectancy than White people, while, conversely, Hispanic people have consistently had longer life expectancy compared to White people. When life expectancy reached its peak in 2014, life expectancy for Black people was more than three years shorter than White people (75.3 vs. 78.8 years), and Hispanic people had a longer life expectancy at 82.1 years (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1). (Data were not available for other groups.)

Following this peak in 2014, life expectancy declined for the first time in over two decades. Between 2014 and 2017, overall life expectancy declined by 0.3 years with a slightly larger decline for Black people (0.4 years) compared with Hispanic and White people (0.3 years for both) (Figure 1 and Appendix Table 1). Separate data were not reported for Asian, AIAN and NHOPI people for this period. Research suggests that increases in mortality due to suicide, drug overdose and alcohol abuse were drivers of the decreasing life expectancy during this time. In 2018 and 2019, life expectancy remained relatively stable overall and across groups.

Life expectancy sharply declined by 2.7 years between 2019 and 2021, and disparities widened amid the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 2). In 2019, prior to the onset of the pandemic, overall life expectancy was 78.8 years. AIAN people had the lowest life expectancy at 71.8 years, followed by Black people at 74.8. These groups both had lower life expectancies than White people, whose life expectancy was 78.8 years. Hispanic and Asian people had longer life expectancies of 81.9 and 85.6 years, respectively. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 resulted in higher mortality rates. Because life expectancy is based on death rates for a given period, these increased mortality rates drove declines in life expectancy in 2020 and 2021. Overall life expectancy declined by 2.7 years between 2019 and 2021, with AIAN people experiencing the largest life expectancy decline of 6.6 years, followed by Hispanic and Black people (4.2 and 4.0 years, respectively), and a smaller decline of 2.4 years for White people. Asian people had the smallest decline in life expectancy of 2.1 years between 2019 and 2021. These declines further widened gaps in life expectancy for AIAN and Black people compared to White people and reduced the advantage in life expectancy for Hispanic people relative to White people. As of 2021, provisional data show that life expectancy was lowest for AIAN and Black people at 65.2 years and 70.8 years, respectively, compared to 76.4 years for White people and 77.7 years for Hispanic people. It was highest for Asian people at 83.5 years. Data were not available for NHOPI people. Given that life expectancy reflects death rates from a specified year and provisional data from 2022 show that overall mortality declined 5.3% between 2021 and 2022, reflecting a fall-off in COVID-19 deaths, there may be small increases in life expectancy in upcoming years.

Causes of Recent Life Expectancy Declines

The declines in life expectancy between 2019 and 2021 largely reflect an increase in excess deaths amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which disproportionately impacted Black, Hispanic, and AIAN people. KFF analysis finds the pandemic was associated with faster rises in premature mortality rates and resulted in more excess years of life lost for people of color compared to their White counterparts, with people of color accounting for 59% of excess years of life lost while making up 40% of the population. Other analysis further finds that COVID-19 mortality had the largest contribution to the decline in life expectancy between 2020 and 2021 among AIAN, Black and White people, accounting for 21.4%, 35.0%, and 54.1% of their declines, respectively. Among Hispanic and Asian people, COVID-19 had the second largest contribution to the decline in life expectancy, accounting for 25.5% and 16.6% of their declines, respectively. The largest contributor to the decline for Hispanic people was an increase in mortality due to unintentional injuries, while growth in cancer deaths was the primary contributor to the decline for Asian people between 2020 and 2021.

Although COVID-19 mortality was a primary contributor to the recent decrease in life expectancy across groups, leading causes of death varied by race and ethnicity. Overall, COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death in 2021, after heart disease and cancer. However, COVID-19 was the top leading cause of death for Hispanic and AIAN people, followed by heart disease and cancer (Figure 3). Among Black, Asian, and White people, COVID-19 was the third leading cause of death, outranked by heart disease and cancer.

Beyond COVID-19 becoming a leading cause of death, there were other changes in leading causes of death that occurred during the pandemic (Figure 3). For example, flu activity has been lower since the beginning of the pandemic, leading to flu and pneumonia falling out of the ten leading causes of death in 2021. In contrast, liver disease rose to the ninth leading cause of death, reflecting sharp increases in alcohol-related deaths during the pandemic, with AIAN people experiencing the largest increase from 44.7 per 100,00 in 2019 to 77.8 per 100,000 in 2021. Deaths related to unintentional injuries also increased between 2019 and 2021, largely driven by increases in drug overdose deaths. Although suicide rates dropped out of the top ten leading causes of death overall during the pandemic (10th leading cause of death in 2019 vs. 11th in 2021), there was a significant increase in suicide deaths between 2020 and 2021 among Black and White men and women and AIAN men, and suicide remained the ninth leading cause of death for AIAN people and the tenth leading cause for White people in 2021. Although homicide deaths increased between 2020 and 2021, Black people are the only racial group for which homicide was a top ten cause of death in 2021, reflecting high rates of homicide among young Black men. For example, homicide was the leading cause of death in 2021 among Black males ages 15-34, and the death rate was 20 times higher than their White counterparts (126.1 per 1000,000 vs. 6.1 per 100,000), continuing a disparity in homicides that has existed for decades.

Provisional data from 2022 show that overall mortality declined 5.3% between 2021 and 2022, and that, in 2022, the three leading causes of death were heart disease, cancer, and unintentional injuries. During this time, COVID-19 deaths declined almost 50% overall and across all racial and ethnic groups, dropping to the fourth leading cause of death. Despite these declines in COVID-19 deaths, AIAN and Black people continued to have higher COVID-19 death rates compared to White people. Declining death rates from COVID-19 may improve life expectancy overall, however racial gaps will likely persist given the continued disparities in COVID-19 and other leading causes of death.

Factors Contributing to Racial Life Expectancy Disparities

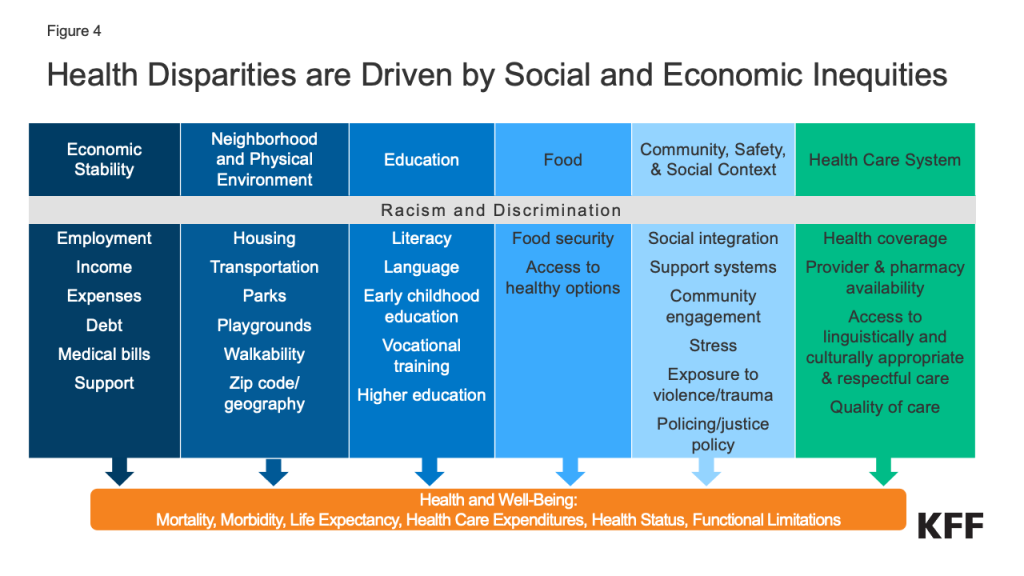

Research suggests that the factors driving disparities in life expectancy are complex and multifactorial. They include differences in health insurance coverage and access to care, social and economic factors, and health behaviors that are rooted in structural and systemic racism and discrimination (Figure 4).

People of color are more likely than their White counterparts to be uninsured and to face other barriers to accessing health care that may contribute to shorter life expectancy. Data show that people of color are less likely to have health insurance and more likely to face barriers to accessing care, such as not having a usual source of care. Among AIAN people, chronic underfunding of the Indian Health Service further contributes to barriers to health care. Research shows that, overall, uninsured people are more likely than those with insurance to go without needed medical care due to cost and less likely to receive preventive care and services. Research further shows that uninsured people have higher mortality rates and lower survival rates than people with insurance.

Underlying social and economic inequities also drive disparities in mortality and life expectancy. Hispanic, AIAN, and Black people are more likely to have lower incomes and educational attainment levels compared to White people, and studies find that people with higher incomes and more education live longer lives. Other social and economic factors may also affect life expectancy. For example, historic housing policies, including redlining, and ongoing economic inequities have resulted in residential segregation that pushed many low-income people and people of color into segregated urban neighborhoods. Research finds that living in racially segregated neighborhoods is associated with shorter life expectancy and higher mortality rates for Black people.

Social and economic factors can also shape health behaviors and exposure to health risks that influence life expectancy, For example, Black and AIAN people have higher rates of smoking, substance and alcohol use disorders, and obesity compared to White people. Research suggests that eliminating smoking and obesity would greatly narrow disparities in life expectancy between Black and White people. People of color are also disproportionately affected by violence, including police and gun-related violence. Research shows African American and AIAN men and women and Latino men are at increased risk of being killed by police compared to their White peers. Black and Hispanic adults also are more likely than White adults to worry about gun violence according to 2023 KFF survey data. Other KFF analysis shows that firearm death rates increased sharply among Black and Hispanic youth during the pandemic driven primarily by gun assaults and suicide by firearm.

Research also highlights the role of racism and discrimination in driving racial disparities in mortality. Many of the inequities described above are rooted in racism and discrimination. Racism also contributes to lower quality of care among people of color. For example, a KFF/The Undefeated survey found that most Black adults believe the health care system treats people unfairly based on their race, and one in five Black and Hispanic adults report they were personally treated unfairly because of their race or ethnicity while getting health care in the past year. Beyond driving structural inequities and differences in experiences obtaining health care, research also demonstrates that racism and discrimination have direct negative impacts on health. For example, research finds that the cumulative effects of exposure to racism and chronic stress, referred to as allostatic load, may contribute to a more rapid decline in health and higher mortality among Black people. The health of AIAN people has also been negatively affected by ongoing racism and discrimination, and intergenerational trauma stemming from historical actions and policies, including genocide, removal from native lands, and assimilation efforts, including Indian boarding schools.

Some life expectancy patterns are not fully understood or observable in the data presented. Notably, Hispanic people have longer life expectancy than their White counterparts despite experiencing increased barriers to accessing health care and social and economic challenges typically associated with poorer health outcomes. Researchers have hypothesized that this finding, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic or Latino health paradox, in part, may stem from variation in outcomes among subgroups of Hispanic people by origin, nativity, and race, with better outcomes for some groups, particularly recent immigrants to the U.S. However, the findings still are not fully understood. Measures of life expectancy for Asian people as a broad group may mask underlying differences among subgroups of the population who vary across health access and social and economic factors. Research has shown variation in life expectancy among Asian subgroups, with Chinese people having the longest life expectancy and Vietnamese people having the shortest life expectancy, which may in part reflect differences in socioeconomic status. Additionally, data limitations for NHOPI people prevented the ability to include them in this analysis. Efforts to expand and improve data collection for NHOPI people will be important to gain a better understanding of their experiences, particularly since they suffered disproportionate impacts on mortality from COVID-19.

Conclusion

Overall, the data suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated longstanding racial disparities in life expectancy. The recent declines and widening of disparities in life expectancy highlight the urgency and importance of addressing disparities in health broadly and increased attention to disparities in mortality and life expectancy specifically. Continued efforts within and beyond the health care system will be important to reduce ongoing racial disparities in life expectancy, many of which are rooted in systemic racism. Within the health care system, these may include ongoing efforts to reduce gaps in health insurance, increase access to care, and eliminate discrimination and bias. Beyond the health care system, addressing broader social and economic factors, including those that drive disparities in behavioral risks, will also be important.